Abstract

Objective

This study explored how male and female family caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients differ in their use of formal services and informal support and how religiousness may affect such differences.

Methods

Data were from a sample of 720 family caregivers of AD patients who participated in the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Heath (REACH I) study sites in Birmingham, Boston, Memphis, and Philadelphia.

Results

Female caregivers were less likely to use in-home services than males (M = 0.83 vs. M = 1.06, p < .01) but reported more use of transportation services (21.6% vs. 12.7%, p < .01) and more use of informal support (M = 13.9 vs. M = 10.7, p < .01). Mediation tests suggested that three measures of religiousness helped explain the relationship between gender and use of formal services and informal support.

Discussion

These findings highlight the necessity to assess AD caregivers’ religiousness to better understand their circumstances.

Keywords: gender, Alzheimer’s caregiving, religiousness, service use

Women have had a long history as the primary caregivers in American society. With medical advances and increased longevity, this has increasingly included care of older adults. These same factors have also resulted in an increase in the number of males providing care to adults, most often spouses. Males, however, have not had the same tradition of and experiences with caregiving that females have had and thus might approach the task somewhat differently (Calasanti & Bowen, 2006).

A substantial proportion of current female AD caregivers was born in the first third of the 20th century and formed many of their views on caregiving during the 1930s and 1940s. Caregiving, both of children and adults, during this time was largely a family/friend matter. Day care was not readily available, elder care programs were nonexistent, and the proportion of married women who worked outside the home was low (Velkoff & Lawson, 1998). Consequently, care systems were largely informal.

Beyond the family, the primary institution that provided support and help to individuals was the church. Mothers, perhaps because they had primary responsibility for the socialization of their children, were more heavily involved with the church and thus could, at least on occasion, find support and assistance from the church community (Levitt, 1995). Males from this same era had primary responsibility for providing financially for the family and had less involvement in direct care of children or, in those cases where it occurred, adult care. They also generally had less involvement with the church, at least as a system of social support (Francis, 1997).

The biographical context of current caregivers not only influences their knowledge about various types of services but also their perceptions of gender roles and religiousness. This study addressed how male and female family caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients differ in their use of formal services and informal support and how religiousness may affect any differences.

Previous work on the relationship of caregivers’ gender to their use of informal support reveals no consistent pattern. Collins and Jones (1997) did not find differences in the use of informal support in a study of husband and wife caregivers. Ingersoll-Dayton, Starrels, and Dowler (1996) found that men used more informal support from friends and families with caregiving tasks than women, whereas Wallsten (2000) found that female caregivers had more informal support than males. Pinquart and Sorensen’s (2006) meta-analysis suggests that the gender differences may be smaller than expected because women have larger social networks available to them, but male caregivers are more motivated than female caregivers to seek assistance. This could be because male caregivers are less prepared for and less comfortable with the caregiving role (Stoller & Cutler, 1992).

Research on gender differences in the use of formal services is also mixed. The widely adopted Andersen behavioral model (1995) suggests gender is a predisposing factor that influences health service use. However, empirical studies to date have not found a relationship between gender and overall formal service use (Bookwala et al., 2004; Tennstedt, Crawford, & Delgado, 1998). Thus, if gender differences exist, they may be contingent on the specific type of formal service under examination. For example, there is evidence that male caregivers are more likely than females to use in-home services to take care of their relatives (Kadushin, 2004; Larsson & Thorslund, 2002). Alkema, Reyes, and Wilber (2006) found that high-risk older women were more likely than men to use transportation services. Given the few studies in this area, Pinquart and Sorensen (2006) suggest that more research needs to be focused on gender differences in the use of specific formal services.

The relationship between religion and help-seeking behavior of older adults and their caregivers has also received research attention. Some studies suggest that religious organizations may substitute for or supplement the assistance provided by informal networks and formal service agencies (Delgado, 1996; Naleppa & Reid, 2003). In a study of older African Americans, Williams and Dilworth-Anderson (2002) found that churches helped link their members to more formal services, but not to the use of informal support. A recent national study found religious attendance to be associated with use of preventive health services (Benjamins, Trinitapoli, & Ellison, 2006). However, religiousness was negatively related to health service use in a study of African American and White older women (Ark, Hull, Husaini, & Craun, 2006). Findings from a qualitative study suggest religiosity can either impede or prompt the help seeking of family caregivers (Levkoff, Levy, & Weitzman, 1999). Because of the limited number studies in this area and the conflicting findings, the evidence to date is less than conclusive.

Gender differences in religiousness might result from specific gender-typed socialization. According to social role theory, gender differences are due to the different social demands on men and women and are often associated with differences in race, ethnicity, social class, and religion (Eagly, 1987; Kaye, 2002). Women and men internalize gender differences because they act in accordance with their social roles, which are associated with different expectations and require different skills. Religion comprises a significant part of socialization in any society, and males and females approach and practice religion differently. Females are routinely found to be more likely to engage in religious activities than males (Navaie-Waliser, Spriggs, & Feldman, 2002; O’Connell, Saxena & Underwood, 2006; Stark, 2002). Understanding male–female religiousness differences might contribute to knowledge about gender differences in use of informal support and formal service use.

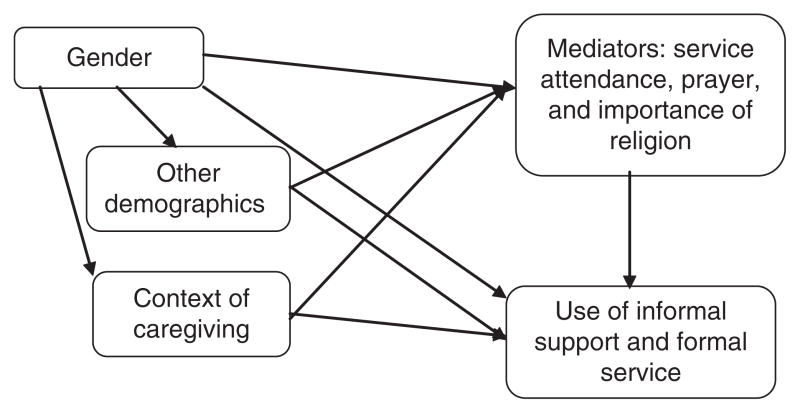

Our literature review leads us to conclude that gender differences in the use of informal support and formal services are complex. The present study pursued two aims. The first was to determine whether there were gender differences in the use of informal support and specific formal services among AD caregivers. The second was to determine if such differences could be explained by the nature of the caregiver’s religious involvement. We used Pearlin’s coping-stress model (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) to organize potential predictors into sociodemographics, caregiving context variables, and mediators (see Figure 1). We formed the following hypotheses: (a) Female caregivers use more informal support than male caregivers; (b) Female caregivers use fewer in-home services, but more outside home services (e.g., transportation, support group, and day care services) than male caregivers; and (c) religiousness, particularly religious service attendance, mediates the relationship between gender and use of informal support and formal services.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Method

Participants

This study used baseline data from the 295 African American and 425 Caucasian participants from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health I (REACH I) project sites in Birmingham, Memphis, Philadelphia, and Boston. Because of the small number of male Hispanic caregivers in the overall REACH I study, we excluded participants from the Palo Alto and Miami (sites with substantial proportions of female Hispanic caregivers) and all Hispanic caregivers in the remaining sites (n = 20) from this study. The resulting sample included 165 male and 555 female caregivers.

Recruitment

Family caregivers of dementia patients living in communities were recruited from memory disorder clinics, primary care clinics, social service agencies, and physicians’ offices. See Schulz et al. (2003) for details about recruitment for the REACH I project. To be included in the study, care recipients had to have a medical diagnosis of probable AD or exhibit a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of less than 24. In addition, care recipients had to have at least one basic activity of daily living (ADL) limitation (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963) or two instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations (Lawton & Brody, 1969). All caregivers in the study had to be at least 21 years old, live with the care recipient, and consider themselves to be the primary caregiver. They also must have provided an average of at least 4 hours of daily care for the recipient for at least 6 months. Data for this study were collected through in-home interviews during the baseline phase.

Measures

Dependent variables

A scale developed by the REACH I research team (Gitlin, et al., 2003) measured the use of formal services. Seven questions asked caregivers whether or not they used a particular type of formal service in the last month. To measure use of in-home services, we counted how many of the following four services participants used in the last month: homemaker, home health, visiting nurse, and meals delivered to home (scores could thus range from 0 to 4). Cronbach’s alpha for this set of questions was .60. Three types of out-of-home services included transportation, day care, and support group services. Cronbach’s alpha for these three items was .44. Thus, we elected not to combine these items in the analysis. See detailed information about these measures in Harrow et al. (2004).

Informal support was measured by the amount of actual help the caregiver reported receiving using an 11-item instrument based on work by Krause and Markides (1990). Specific items included tangible support, (e.g., help with transportation), emotional support, (e.g., having others listen and show interest), and informational support, (e.g., sharing suggestions). Response choices ranged from 0 for never to 3 for very often. Factor analysis of the items indicated all had reasonable loadings on a single factor. Item scores were added together resulting in an index with a possible range of scores from 0 to 33. Coefficient alpha for this measure with this sample was .81.

Mediating variables

Religiousness is generally considered to be a multidimensional concept (Hill & Hood, 1999; Idler, et al., 2003; Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). Religiousness in this study was assessed with three separate items that deal with three different dimensions of religiousness (Koenig & Futterman, 1995). Participants reported how often they attended religious services or activities (never = 1 to nearly very day = 6), and how frequently they prayed or meditated (never = 1 to nearly every day = 6). Participants also indicated how important religious faith or spirituality was to them (not important = 1 to very important = 4).

Possible control variables

Other variables in the study that might affect the relationship between gender and use of formal and informal support included care recipients’ cognitive ability, the amount of help with ADLs and IADLs provided by the caregiver, and caregivers’ sociodemographic and health-related characteristics. Care recipients’ cognitive impairment was measured by the MMSE. We counted how many of 14 ADL and IADL activities the care recipient needed assistance with, and how many of them were assisted by family caregivers. Sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers included age, race (African American or Caucasian), years of education, relationship to care recipient (spouse or other), years taking care of the care recipient, and household income. Household income was measured on a 10-point scale (0 through 4 are $5000 ranges from 0 to $20,000 and 5 through 9 are $10,000 ranges from $20,000 to $70,000 or more). Caregiver perceived health was measured by a single item “How do you evaluate your health? ” on a 5-point Likert-type scale from very bad (1) to very good (5).

Analysis Plan

We used t tests to determine whether there were gender differences on all the variables of interest. Potential control variables that showed gender differences were entered into the mediation analyses. These included caregiver age, income, education, and race, as well as relationship to care recipient. Following Baron and Kenny’s suggestions (1986), we next examined whether each of the three measures of religiousness was correlated with the measures of formal and informal support. We conducted mediation analyses on the use of informal support and in-home services using SPSS macros developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008). This method produces confidence intervals for the estimated effects based on a bootstrapping method and allows us to determine the combined effects of the three religiousness measures and the specific mediating effect for each mediator simultaneously. We conducted two-step logistical regression analysis to detect mediating effects of religiousness on use of out-of-home services because the out-of-home services were dichotomies.

Results

Gender Differences in Use of Formal Services and Informal Support

Males reported using more in-home services than females. Females were more likely to receive informal support than males and more likely to use transportation services. There were no statistically significant gender differences in the use of day care or support group services (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Gender Differences in Use of Formal Services and Informal Support and Characteristics of Caregivers

| Males (n = 165) | Female (n = 555) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of formal services | |||

| In-home services, mean (SD) | 1.06 (1.17) | 0.83 (1.06) | .01 |

| Transportation, % | 12.7 | 21.6 | .01 |

| Day care services, % | 20.6 | 28.1 | .06 |

| Support group services, % | 8.8 | 10.4 | .58 |

| Use of Informal support, mean (SD) | 10.7 (6.3) | 13.9 (6.6) | .00 |

| Religiousness | |||

| Frequency of service attendance, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.8 (1.5) | .01 |

| Frequency of prayer, mean (SD | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.1) | .02 |

| Importance of religion, mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.6 (0.8) | .01 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 72.8 (14.8) | 67.2 (12.7) | .01 |

| Spouse of care recipient, % | 60.0 | 42.1 | .01 |

| Education, mean (SD) | 11.2 (3.3) | 10.3 (3.7) | .01 |

| Yearly household incomea, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.3) | .03 |

| African American, % | 32.7 | 43.4 | .02 |

| Context of caregiving | |||

| Years taking care of care recipient, mean (SD) | 4.3 (4.1) | 4.1 (3.6) | .50 |

| CG general health, mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.89 (1.0) | .12 |

| CR needed ADL/IADL help, mean (SD) | 11.1 (2.6) | 11.1 (2.3) | .85 |

| CG provided ADL/IADL help, mean (SD) | 12.4 (2.0) | 12.9 (2.1) | .24 |

| CR MMSE, mean (SD) | 11.1 (7.5) | 12.2 (7.3) | .12 |

Note: SD = standard deviation; CG = caregiver; CR, care recipient; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam.

4.6 indicates a yearly income of approximately $35,000; 4.1 indicates a yearly income around $30,000.

Gender Differences in Demographics and Religiousness

Although some younger caregivers were included in the sample, 73% of participants were 60 years of age or older. Female caregivers were younger, and were more likely to be African American, caring for someone other than their spouse, of lower income, and to have lower educational levels than their male counterparts. Males and females did not differ in their years of taking care of the care recipient, self-rated health, or ADL/IADL help given to the care recipient. Care recipients of males and females did not differ on cognitive status nor on the number of ADL/IADL difficulties they had. Females scored higher on each of the three measures of religiousness than did males.

Relation Between Religiousness and Use of Formal Services and Informal Support

Frequency of attendance at religious services, frequency of prayer, and importance of religion had statistically significant negative correlations with use of in-home services and statistically significant positive correlations with informal support (see Table 2). Of the three measures of religiousness used in this study, only frequency of service attendance was related to use of transportation services. Those who attended religious services less frequently were more likely to use transportation services.

Table 2.

Pearson Product–Moment Correlations Among Religiousness, Use of Formal Services, and Informal Support

| Frequency of Service Attendance | Frequency of Prayer | Importance of Religion | Transportation | In-Home Services | Informal Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of service attendance | 1.00 | .30** | .36** | −.09* | −.11** | .11** |

| Frequency of prayer | 1.00 | .61** | −.05 | −.12** | .11** | |

| Importance of religion | 1.00 | −.05 | −.10** | .13** | ||

| Transportation | 1.00 | .15** | .08* | |||

| In-home services | 1.00 | .02 | ||||

| Informal support | 1.00 |

p < .05 level (two-tailed).

p < .01 level (two-tailed).

Mediation Analysis With Use of Transportation as an Outcome

Customarily, mediation analysis requires that the independent variables be related to both the mediating variables and the dependent variables and that the mediation variables be related to the dependent variables (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Because gender did not have statistically significant relationships with either use of day care service or use of support group services, neither of these variables was included in the mediation analyses. Because neither frequency of prayer nor importance of religion was related to use of transportation services, they were excluded from the equations predicting use of transportation services.

Logistic regression analysis indicated that females were more likely than males to use transportation services (β = .66, SE = .27, p < .05; see Table 3). However, when frequency of religious service attendance was introduced, controlling for caregiver age, income, education, race, and relationship to the care recipient, the relationship between gender and transportation use disappeared (β = .03, SE = .33, p > .05). At the same time, those who attended religious services more frequently, were less likely to use transportation services (β = −.20, SE = .07, p < .01). Although there is no calculated value of the indirect effect of gender via religious service attendance in use of transportation, the pattern of results we found suggested that attendance at religious services mediated the relationship between gender and use of transportation services.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression of Gender and Gender Plus Religiousness as Predictors of Use of Transportation Services

| Use of Transportation |

||

|---|---|---|

| βa | SE | |

| Model 1 | ||

| Gender | .66* | .27 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Gender | .03 | .33 |

| Frequency of service attendance | −.20** | .07 |

| Pseudo R2 = .09 | ||

Note: Gender was coded 0 = male and 1 = female. Effects net of controlling for caregiver age, educational attainment, income, race, and relation to the care recipient in Model 2.

β stands for values of unstandardized coefficients.

p < .05 level (two-tailed).

p < .01 level (two-tailed).

Mediation Analyses With Use of In-Home Services and Informal Support as Outcomes

Females were less likely to use in-home services than were males, even when controlling for caregiver age, race, income, education, and relationship to care recipient (β = −.36, SE = .15, p < .05; see Table 4). The composite indirect path of gender through the three measures of religiousness to use of in-home services was statistically significant (β = −.08, SE = .03, p < .05), suggesting that religiousness partially explained the relationship between gender and use of in-home services. Two of the components of the indirect relationship of gender through religiousness to use of in-home services were statistically significant—frequency of service attendance (β = −.04, SE = .02, p < .05) and frequency of prayer (β = −.03, SE = .02, p < .05).

Table 4.

Gender’s Direct Effect and Indirect Effect Through Religiousness on Use of In-Home Services and Informal Support Using the Preacher and Hayes (2005) Mediation Technique

| In-Home Services |

Informal Support |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | SE | βa | SE | |

| Gender alone | −.24* | .10 | 3.10** | .59 |

| Gender directb | −.36* | .15 | 1.11 | .90 |

| Gender indirect totalb | −.08* | .03 | .34* | .19 |

| Via service attendance | −.04* | .02 | .09 | .14 |

| Via frequency of prayer | −.03* | .02 | .13 | .14 |

| Via importance of religion | −.01 | .02 | .12 | .13 |

| R2 | .034 | .082 | ||

β stands for values of unstandardized coefficients.

Effects net of caregiver age, educational attainment, income, race, and relation to the care recipient.

α < .05.

α < .01.

Mediation Analysis With Use of Informal Support as an Outcome

Gender had a statistically significant relationship with level of informal support (β = 3.10, SE = .59, p < .01) that ceased to be statistically significant when the measures of religiousness were introduced into the equation. The overall indirect effect of gender through the three measures of religiousness to level of informal support was statistically significant β = .34, SE = .19, p < .05). However, the indirect effect of gender through each of the specific religiousness measure was not significant. Further analysis with each individual religiousness item as a mediator without two other religiousness items in the equation found significant indirect effects with prayer (β = .23, SE = .15, p < .05) and with importance of religiousness(β = .21, SE = .14, p < .05).

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to identify differences between male and female AD caregivers in their receipt of specific formal services and their use of informal support. Consistent with Pinquart and Sorensen’s (2006) suggestions, our findings indicated that gender differences in use of formal support varied by the type of service under consideration, independent of the effects of income and education level. We did not find gender differences in participants’ physical functioning, health, and cognitive status, and therefore ruled out the contributions of such variables to gender differences in use of formal services and informal support. We found that females used fewer formal in-home services, a finding consistent with the studies of Stoller and Cutler (1992) and Tennstedt, Crawford, and McKinlay (1993), and that females used more transportation services. Given that women are traditionally accustomed to in-home tasks, they may perceive less difficulty in performing such tasks, and thus might be less inclined to seek and receive outside assistance. Male caregivers in this sample were significantly older than their female counterparts. It may be that they were less prepared to perform in-home tasks in their early lives and thus they tended to seek out and receive more assistance in this regard. Consistent with gender role theory, women may be less comfortable with driving their spouses with dementia and may thus find community transportation services a more useful alternative.

We found that females were more likely to use informal support than males, which is consistent with some previous studies (Wallsten, 2000), but contrary to others (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 1996). Subsequent analysis of these data found that males reported having fewer relatives (M = 9.06, SD = 3.74 for males and M = 9.99, SD = 3.06 for females, t(738) = −3.32, p ≤ .001), friends (M = 7.04, SD = 5.00 for males and M = 7.88, SD = 4.07 for females, t(738) = −2.26, p < .05), and confidants (M = 5.31, SD = 2.82 for males and M = 6.82, SD = 2.43 for females, t(738) = −6.88, p ≤ .001) than did females, which may help explain their lower use of social support. Another explanation for this finding may be that female caregivers acknowledge relying on their families, relatives, and friends for support, whereas male caregivers may be hesitant to report this type of support. Thus, the use of informal support by men could be underreported.

A major focus of this study was whether the abovementioned relationship between gender and different types of support was influenced by religiousness. Consistent with previous work (Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002), female caregivers scored higher on each of the measures of religiousness than did male caregivers. We also found that religious service attendance helped explain gender differences in the use of transportation services. Although females were more likely to attend religious services than males, those who did not attend often were more likely to use transportation services. This might mean that caregivers who had trouble getting to church themselves were also more likely to need transportation services for the care recipient. These could be caregivers who never learned to drive or those who currently found themselves unable to drive with a disabled care recipient.

We found that frequency of service attendance and frequency of prayer partially mediated the relationship between gender and use of in-home formal services. It should be noted, however, that the magnitude of these relationships was small. Women who prayed and attended services more often were less likely to use in-home services. Attending services might link one to a helping community that shares and provides support in the tasks of caregiving, thus reducing the need for formal help. Prayer might also reduce the stresses of caregiving and thus the need for formal services. Given that both prayer and church attendance involve an expenditure of time, another possible explanation is that women who had time to attend services or pray might take care of a care recipient who required less care.

Religiousness also appeared to help explain the relationship between gender and use of informal support. The direct effect from gender to informal support was no longer statistically significant when the religiousness items were introduced. Although none of the three individual paths from gender through the measures of religiousness to use of informal support was statistically significant, the combined effect of the three measures was. These three dimensions of religiousness appeared to operate together in their influence on informal support. However, this finding needs to be approached with caution. It could be due to the close associations between the frequency of prayer and importance of religiousness, as further analysis with each individual religious item as a mediator found significant indirect effects with prayer and with importance of religiousness.

There are several methodological limitations associated with this secondary data analysis. We employed a sample with a substantial group of male (165) and female (555) caregivers. However, the sample was not a probability sample. Family caregivers were recruited via local AD diagnostic and support centers, community and social service agencies, and physicians’ offices. Caregivers recruited through these sources may not represent those who are uncomfortable with seeking outside assistance or those who experience strain that is not severe enough to request help. Another limitation is our inability to calculate the indirect effect of gender via religiosity on transportation service use due to the unavailability of an appropriate analytical technique. The two-step logistical regression analyses allowed us to detect a mediation effect by comparing the β differences in two regression steps, but could not generate a value for this mediation effect. Finally, as is often the case in studies of service utilization, the data on service use were skewed, which partly explained a low R2 value for the mediation model. Generally, however, regression analysis is robust to violations of normality as long as the sample size is not small (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

In spite of the abovementioned limitations, the findings of this study add to current AD caregiving literature, by shedding light on how caregivers’ religiousness and gender are related to their use of informal and formal services. Our findings provide evidence that female and male caregivers differed in their use of informal support, that gender differences in formal service use were contingent on the specific type of services, and that religiousness helped explain such gender differences. If our assumptions about the socialization of the current cohort of AD caregivers are accurate, these findings from a group of caregivers, most of whom were born before 1940, reinforce the importance of using a life course perspective to understand gender role and religious socialization as they influence informal support and formal service use.

Findings of this study are of practical significance in terms of serving dementia caregivers, particularly those who fall through governmental program gaps. Because of the 2000 Older Americans Act amendment, National Family Caregiver Support Programs have been established across the country to help family caregivers to continue their caregiving efforts, which in turn, will allow care recipients to remain in the community for a longer period of time. However, due to lack of staff and limited budgets, the waiting period for admission to these programs may be lengthy, and not all caregivers are eligible. For those who are not eligible or those on the waiting list but in need of help, local agency case workers or program administrators may consider religious resources in the community as a way to assist dementia caregivers and their families. Collaboration with religious organizations could include referral of clients, helping establish respite care in churches, and providing health education to dementia caregivers in faith-based settings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grants: Burgio U01-NR13269, Burns U01-AG13313, Eisdorfer U01-AG13297, Gallagher-Thompson U01-AG13289, Gitlin U01-AG13265, Mahoney U01-AG13255, Schulz U01-AG13305). Partial support was also provided by the Center for Mental Health and Aging at the University of Alabama.

Contributor Information

Fei Sun, Arizona State University, Phoenix.

Lucinda Lee Roff, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

David Klemmack, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Louis D. Burgio, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

References

- Alkema GE, Reyes JY, Wilber KH. Characteristics associated with home-and community-based service utilization for Medicare managed care consumers. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:173–182. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ark PD, Hull PC, Husaini BA, Craun C. Religiosity, religious coping styles, and health service use: Racial differences among elderly women. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2006;32:20–29. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20060801-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR, Trinitapoli J, Ellison CG. Religious attendance, health maintenance beliefs, and mammography utilization: Findings from a nationwide survey of Presbyterian women. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Zdaniuk B, Burton L, Lind B, Jackson S, Schulz R. Concurrent and long-term predictors of older adults’ use of community-based long-term care services: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16:88–115. doi: 10.1177/0898264303260448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T, Bowen ME. Spousal caregiving and crossing gender boundaries: Maintaining gendered identities. Journal of Aging Studies. 2006;20:253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Jones R. Emotional distress and morbidity in dementia caregivers: A matched comparison of husbands and wives. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;12:1168–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M. Religion as a caregiving system for Puerto Rican elders with functional disabilities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1996;26(34):129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LJ. The psychology of gender difference in religion: A review of empirical research. Religion. 1997;27:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Belle SH, Burgio L, Czaja S, Mahoney D, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Effect of multi-component interventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH multi-site initiative at 6 months follow-up. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:361–374. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow BS, Mahoney DF, Mendelsohn AB, Ory MG, Coon DW, Belle SH, et al. Variation in cost of informal caregiving and formal-service use for people with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2004;19:299–308. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW, editors. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George L, Krause N, Ory NG, et al. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research. Research on Aging. 2003;25:327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Starrels ME, Dowler D. Caregiving for parents and parents-in-law: Is gender important? The Gerontologist. 1996;36:483–491. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin G. Home health care utilization: A review of the research for social work. Health & Social Work. 2004;29:219–244. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffee MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye LW. Service utilization and support provision of caregiving men. In: Kramer BJ, Thompson EH, editors. Men as caregivers: Theory, research, and service implications. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 359–385. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Futterman A. Religion and health outcomes: A review and synthesis of the literature. Proceedings of conference on methodological approaches to the study of religion, aging and health; Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1995. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Markides K. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1990;30:37–53. doi: 10.2190/CY26-XCKW-WY1V-VGK3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson K, Thorslund M. Does gender matter? Differences in patterns of informal support and formal services in a Swedish urban elderly population. Research on Aging. 2002;24:308–336. [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff S, Levy B, Weitzman PF. The role of religion and ethnicity in the help seeking of family caregivers of elders with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:335–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1006655217810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M. Sexual identity and religious socialization. British Journal of Sociology. 1995;46:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody E. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naleppa MJ, Reid WJ. Gerontological social work: A task centered approach. New York: Columbia University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Navaie-Waliser M, Spriggs A, Feldman P. Informal caregiving: Differential experiences by gender. Medical Care. 2002;40:1249–1259. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036408.76220.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell KA, Saxena S, Underwood L. A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1486–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Gender difference in caregiver stressor, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology. 2006;61B:33–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KI, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, Gitlin L, Wisniewski SR, Ory MG. Introduction to the special section on Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:357–360. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller EP, Cutler SJ. The impact of gender on configurations of care among married elderly couples. Research on Aging. 1992;14:313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt S, Crawford S, Delgado M. Patterns of long-term care: A comparison of Puerto Rican, African American, and non-Latino White elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1998;30:179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt S, Crawford S, McKinlay JB. Determining the pattern of community care: Is co-residence more important than caregiver relationship? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1993;48:S74–S83. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velkoff VA, Lawson VA. International Brief (IB/98-3) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 1998. Gender, aging and caregiving. [Google Scholar]

- Wallsten SS. Effects of caregiving, gender, and race on the health, mutuality, and social supports of older couples. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:90–111. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SW, Dilworth-Anderson P. Systems of social support in families who care for dependent African American elders. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:224–236. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]