SUMMARY

The need to sleep grows with the duration of wakefulness and dissipates with time spent asleep, a process called sleep homeostasis. What are the consequences of staying awake on brain cells, and why is sleep needed? Surprisingly, we do not know whether the firing of cortical neurons is affected by how long an animal has been awake or asleep. Here we found that after sustained wakefulness cortical neurons fire at higher frequencies in all behavioral states. During early NREM sleep after sustained wakefulness, periods of population activity (ON) are short, frequent, and associated with synchronous firing, while periods of neuronal silence are long and frequent. After sustained sleep, firing rates and synchrony decrease, while the duration of ON periods increases. Changes in firing patterns in NREM sleep correlate with changes in slow-wave-activity, a marker of sleep homeostasis. Thus, the systematic increase of firing during wakefulness is counterbalanced by staying asleep.

Keywords: slow wave sleep, slow oscillations, EEG, rat, cerebral cortex, multi-unit recording

INTRODUCTION

During non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep the electroencephalogram (EEG) shows characteristic slow waves that can be recorded over the entire cortical surface (Massimini et al., 2004). It is well known that slow wave activity (SWA, the NREM EEG power between 0.5 and 4 Hz) increases after periods of wakefulness and decreases after periods of sleep (Achermann and Borbely, 2003). For example, staying awake from ~3 to ~24 hours results in progressively higher SWA levels at sleep onset, while naps during the day reduce SWA the following night (Tobler and Borbely, 1986; Vyazovskiy et al., 2006; Werth et al., 1996b). Also, SWA peaks early on during sleep, and decreases thereafter along with the decline in sleep pressure (Achermann and Borbely, 2003). There is also evidence for a regional regulation of slow waves (Cajochen et al., 1999; Oleksenko et al., 1992) and recent studies show that cortical areas that have been “used” more during waking show higher SWA relative to less engaged areas (e.g. (Huber et al., 2004; Kattler et al., 1994)), whereas areas that have been “used” less show reduced SWA (Huber et al., 2006). Thus, at least under acute conditions, sleep SWA can be considered a reliable EEG marker of sleep need, and may thus be related to sleep function (Tononi and Cirelli, 2006).

At the cellular level, it is well known that cortical neuronal firing patterns are characteristically different in NREM sleep compared to both wakefulness and REM sleep (Burns et al., 1979; Desiraju, 1972; Hobson and McCarley, 1971; Murata and Kameda, 1963; Noda and Adey, 1970; Noda and Adey, 1973; Steriade et al., 2001; Verzeano and Negishi, 1960). Intracellular recordings have shown that, during NREM sleep, virtually all cortical neurons engage in the slow (<1 Hz) oscillation, consisting of a depolarized up state, when neurons show sustained firing, and a hyperpolarized down state, characterized by neuronal silence (Amzica and Steriade, 1998; Destexhe et al., 1999; Steriade et al., 1993d; Steriade et al., 2001). There is a close temporal relationship between these cellular phenomena and simultaneously recorded slow (or delta) waves, which are defined as surface-negative EEG events that fall in the SWA frequency range (Amzica and Steriade, 1998; Contreras and Steriade, 1995). Specifically, the surface negativity in the EEG signal (or depth positivity in the local field potential, LFP) corresponds to the down state of cortical neurons as recorded intracellularly, and to the suppression of spiking activity as recorded extracellularly, suggesting that EEG or LFP slow waves are a reflection of near-synchronous transitions between up and down states in large populations of cortical neurons (Burns et al., 1979; Calvet et al., 1973; Contreras and Steriade, 1995; Ji and Wilson, 2007; Luczak et al., 2007; Molle et al., 2006; Mukovski et al., 2006; Murata and Kameda, 1963; Noda and Adey, 1973; Steriade et al., 1993c; Steriade et al., 2001).

Thus, i) sleep EEG slow waves reflect the transition between up and down states of cortical neurons, and ii) EEG SWA is a marker of sleep homeostasis and presumably of sleep need. One might then hypothesize that some aspects of cortical firing may change in relation to sleep pressure. In other words, do cortical neurons fire differently depending on how long the brain has been awake? Surprisingly, this basic question has never been addressed. To fill this gap, we recorded continuously for several days EEG and cortical unit activity in freely behaving rats, during spontaneous sleep/waking cycles as well as after sleep deprivation. We report here that cortical firing patterns do indeed change as a function of sleep homeostasis, in terms of neuronal firing rates, firing synchrony, and distribution of ON and OFF periods.

RESULTS

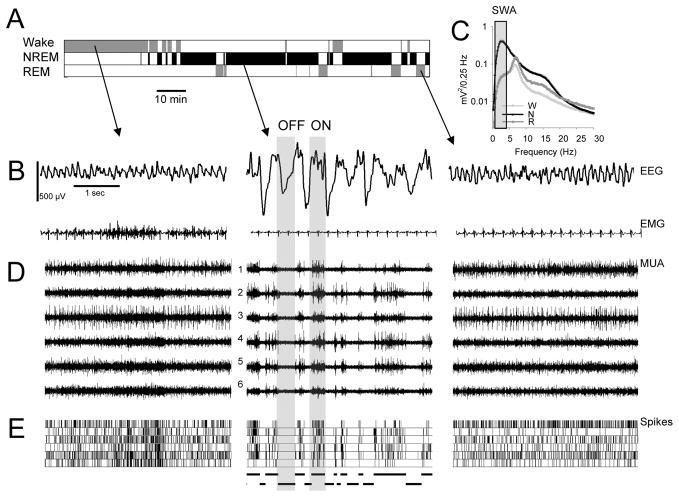

The negative phase of EEG slow waves corresponds to OFF periods in cortical multiunit activity

The EEG during waking and REM sleep is characterized by theta (6–9 Hz) waves and fast frequencies, while in NREM sleep is dominated by high amplitude and low frequency (0.5–4.0 Hz) slow (delta) waves, which account for most of the power in the EEG spectrum (Figure 1A–C). Neuronal activity in the barrel cortex, measured extracellularly using microelectrode arrays (Figure S1–2), also changes dramatically between sleep and waking, with periodic total suppression of neuronal firing during NREM sleep (Figure 1D,E). We call the periods when all recorded neurons are silent for at least 50 ms OFF periods, as opposed to ON periods, when at least a subset of them shows sustained firing (Figure 1E; average duration, ON periods = 815.5 ± 119.9 ms; OFF periods = 85.8 ± 5.9 ms, n=6 rats). The OFF periods occur nearly simultaneously with the negative phase of the slow waves on the surface EEG (Figure 1C–E). Thus, they likely correspond to the down state of the slow oscillations as recorded intracellularly. We use the terms “ON” and “OFF” periods, instead of “up” and “down” or “depolarized” and “hyperpolarized” states (Bazhenov et al., 2002; Steriade et al., 1993d; Steriade et al., 2001), because the periods of neuronal activity and silence were defined based on the population extracellular activity, and not based on changes in membrane potential of individual neurons as measured intracellularly.

Figure 1. Cortical activity in sleep and waking.

(A and B) Hypnogram, EEG traces from the right barrel cortex and corresponding electromyogram (EMG) in a representative rat during a 2-hour interval of undisturbed baseline starting at light onset (positivity is upward). (C) Average EEG power spectra in NREM sleep, REM sleep and waking (mean + SEM, n = 6 rats). Note high values of spectral power in the slow waves range (SWA, 0.5–4.0 Hz; grey bar) in NREM sleep. (D) Raw multiunit activity (MUA) recorded simultaneously in the same rat from a microwire array placed in the left barrel cortex (6 individual channels are shown). Note high tonic firing in waking and REM sleep, and OFF periods in NREM sleep. (E) Raster plots of spike activity for the same 6 channels shown in D (each vertical line is a spike). Note the close temporal relationship between OFF periods and the negative phase of EEG slow waves. Spike sorting was done according to a standard technique (see Experimental Procedures and Figure S1) and the recorded neural population was stable over time (Figure S2).

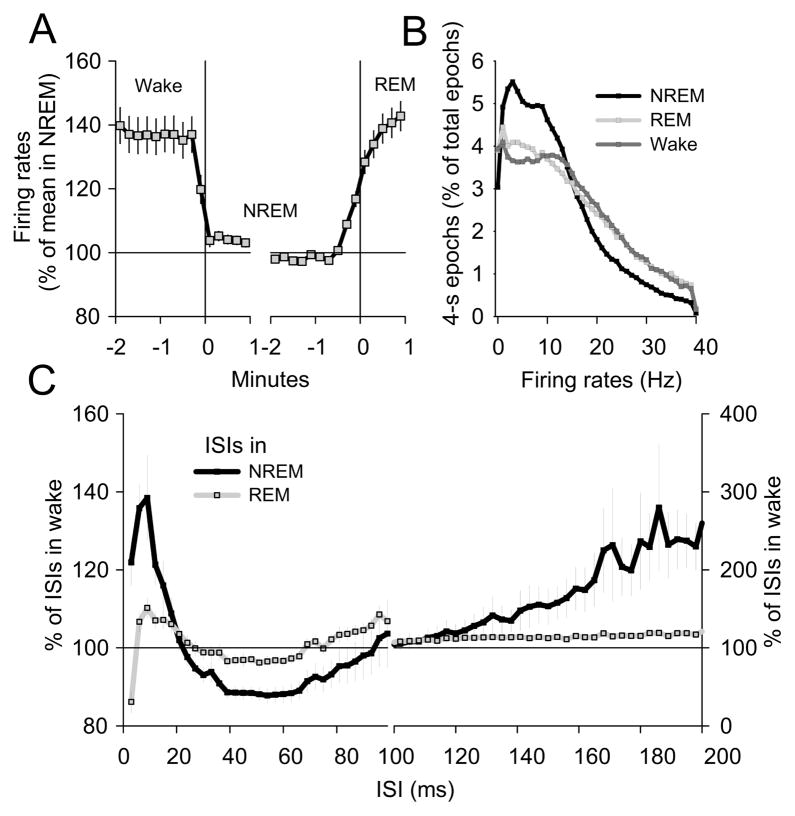

Analysis of neuronal activity based on consecutive 4-sec epochs revealed a rapid decrease of mean cortical firing rates at the transition from waking to NREM sleep, and a gradual increase from NREM to REM sleep (Figure 2A). Overall, periods with high firing rate were more frequent in waking and REM sleep, while periods with low firing rates prevailed in NREM sleep (Figure 2B). Still, firing rates were highly variable within each behavioral state (Figure 2B), likely reflecting different “substates”. For example, during active waking many neurons showed periods of silence of up to several seconds, followed by robust firing often in association with specific behaviors, such as exploring or grooming (data not shown). On average, firing rates were ~ 15–20% higher during active relative to quiet waking (15.4 ± 0.9 vs 13.0 ± 0.8 Hz, p<0.001; quiet waking accounted for <10% of total waking time, consistent with previous reports (Faraguna et al., 2008; Huber et al., 2007a; Huber et al., 2007b)). During NREM sleep, compared to waking and REM sleep, there was a greater proportion of short (<20 ms) interspike intervals (ISIs), likely reflecting high intensity firing during the ON periods, as well as a several fold increase in long ISIs (>100 ms), likely reflecting OFF periods (Figure 2C). Such long ISIs were not only associated with the negativity of EEG slow waves (Figure 1) but also correlated with their amplitude. Thus, high-amplitude slow waves were associated with a more profound suppression of unit activity (Figure 3A), whereas longer OFF periods corresponded to EEG slow waves of higher amplitude (Figure 3B). Since early NREM sleep is characterized by more frequent high-amplitude slow waves (Figure S4), these data suggest that duration and number of the OFF periods could reflect sleep homeostasis.

Figure 2. Effects of vigilance states on cortical neuronal firing.

(A) Time course of mean firing rates during wake-NREM sleep and NREM-REM sleep transitions. Mean values (± SEM) represented as % of mean firing rates in NREM sleep (n=6 rats, 213 neurons). Note that firing rates decrease rapidly after the wake-NREM sleep transition and start increasing ~ 30 sec prior to the onset of REM sleep. (B) Distribution of 4-sec epochs in NREM sleep, REM sleep and waking as a function of mean firing rates (n=6 rats, 213 neurons). Note that high firing rates can be reached in NREM sleep close to the transition to REM sleep (panel A). (C) Distribution of ISIs in NREM sleep and REM sleep represented as % of the corresponding values in waking (mean values ± SEM, n=6 rats, 187 neurons).

Figure 3. EEG slow wave amplitude is related to the duration of the OFF periods.

(A) The profile of average neuronal firing rates in NREM sleep aligned to the negative peak of the EEG slow wave (the peak is not shown, but is indicated by an arrow). Slow waves were subdivided in 3 categories based on their amplitude (low: 1–33%, intermediate: 34–66%, high: 67–100%) and the corresponding averages of neuronal activity were computed. Mean values (n = 6 rats). Note that high amplitude slow waves are associated with a larger suppression of neuronal activity. (B) Average EEG signal, aligned to the onset of OFF periods (arrow). All OFF periods were subdivided into 3 categories: 20–50 ms, 51–100 ms and >100 ms, and the corresponding averages of the EEG signal were computed (n = 6 rats). Note that the occurrence of OFF periods is consistently associated with negative waves in the surface EEG. Moreover, longer OFF periods are associated with larger slow waves.

Number and duration of ON and OFF periods change as a function of sleep pressure

To test this we compared neuronal activity between early sleep, when sleep pressure and SWA are high, and late sleep, when sleep pressure has dissipated and SWA is low (Figure 4A). Visual inspection showed a striking difference: during early sleep, when large slow waves predominate, short ON periods alternated frequently with relatively long OFF periods, whereas in late sleep, when large slow waves are rare, ON periods were longer and only occasionally interrupted by short OFF periods (Figure 4B). A quantitative analysis confirmed that ON periods were initially frequent and short, and became less frequent and longer as sleep pressure dissipated (Figure 4C). Both the incidence and duration of the OFF periods decreased in the course of sleep (Figure 4D; the decrease in the OFF periods duration was correlated with longer ON periods; p<0.001 in all 6 animals). However, while the magnitude of change in the incidence of the ON and OFF periods was similar, the homeostatic change in duration across the day was more pronounced for the ON periods (Figure 4C,D). Notably, changes in the number and duration of ON and OFF periods were highly correlated with the decline in SWA in all animals (Figure 4C,D). The correlation was strongest for the longest OFF periods (>128 ms) and for low EEG frequencies (<4 Hz; not shown).

Figure 4. Homeostatic changes in the patterns of neuronal activity during sleep.

(A) NREM SWA (% of 12-hour baseline) and hypnogram of a 12-hour light period in one representative rat. (B) EEG and raster plots of neuronal activity in early and late NREM sleep in one representative rat. (C) Left: changes in incidence and duration of the ON periods during the light phase in one representative rat. Middle: Mean values (n = 6 rats) of incidence and duration of the ON periods shown for consecutive 4-hour intervals as percentage of the corresponding mean 12-hour value. (D) As in C, but for the OFF periods. Right panels: correlation between SWA (% of 12-hour light period mean) and incidence or duration of the ON and OFF periods in NREM sleep computed for consecutive NREM sleep episodes of the light period in one representative rat (significant correlations were found in all animals).

Neuronal synchrony changes as a function of sleep pressure

In vivo studies have shown that, during early sleep, EEG slow waves are larger and have steeper slopes than in late sleep (Riedner et al., 2007; Vyazovskiy et al., 2007). Computer simulations reproduced these findings and predicted that steeper slow waves might result from a more synchronous recruitment of individual neurons in population ON periods (Esser et al., 2007). Indeed, we found that in early sleep most individual neurons stopped or resumed firing in near synchrony with the rest of the population (Figure 5A). By contrast, in late sleep, the time of entry into ON and OFF periods was much more variable across neurons. To quantify this observation, we computed the latency of the first and last spike of each unit from the onset of population ON or OFF periods, respectively. The synchrony (1/variability) of the latencies decreased by 18% from early to late sleep for ON-OFF transitions, and by 24% for OFF-ON transitions (Figure 5B). We then asked whether changes in neuronal synchronization were related to changes in slow wave slope. Consistent with previous data (Riedner et al., 2007; Vyazovskiy et al., 2007), the slope of surface EEG slow waves was steeper in early sleep compared to late sleep (Figure 5C). Moreover, highly synchronous transitions at the unit level were associated with steep slopes of slow waves, and less synchronous transitions with reduced slopes (Figure 5D). More generally, neuronal synchrony and slow wave slopes were positively correlated (Figure 5E, left panels), whereas the correlation between neuronal synchrony and slow wave amplitudes did not reach significance (not shown). Furthermore, the homeostatic decline of neuronal synchrony at the ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions correlated with the time course of NREM SWA (Figure 5E, right panels).

Figure 5. Decreased synchrony between individual neurons in late sleep.

(A) Raster plots of spike activity in 6 channels during ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions in early and late NREM sleep in one representative rat (each vertical bar represents one spike). Vertical dotted lines show the beginning and the end of the single OFF period depicted in the figure, while vertical thick lines indicate, for each neuron within the recorded population (6 neurons in this case), the average latency of their last and first spike from the onset of the OFF or ON periods, respectively (to assess their synchrony). (B) Neuronal synchrony at the ON-OFF and OFF-ON transition measured as 1/standard deviation (in ms) between the latencies of the last and first spike of each neuron from the onset of population OFF and ON transition, respectively (mean values + SEM, 125 neurons, n = 4 rats). Triangles, p<0.05. (C) Average slopes of the EEG slow waves. Triangles, p<0.05. (D) Average surface EEG slow waves aligned to their start point (ON-OFF transition) or their end point (OFF-ON transition). Mean slow waves (SEM, n=4 rats) are shown for the highest 50% and lowest 50% among all ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions based on the synchrony between individual units (computed as in B). (E). Left: relationship between neuronal synchrony at ON-OFF or OFF-ON transitions and the corresponding slow wave slopes (% of mean). For each individual recording day (n = 4 rats, 2–5 days/rat) all ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions were subdivided into 5 percentiles based on transition synchrony and the corresponding average slow wave slopes were computed. Right. Relationship between NREM SWA (0.5–4.0 Hz, % of 12-hour light period mean) and neuronal synchrony at the ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions computed for the four 3-hour intervals of the light period (n=7 rats, 1–5 days/rat). Lines depict linear regression (Pearson).

Neuronal mean firing rates change as a function of sleep pressure

Next, we asked whether neuronal firing rates were also affected by the sleep-wake history. In rats the longest episodes of wakefulness occur during the night and the longest episodes of sleep during the day. During NREM episodes at night, neuronal firing in the ON periods was intense following sustained wakefulness, and much weaker after sustained sleep (Figure 6A, left panels). To quantify this effect, for each animal we selected two NREM sleep episodes - one after the rat had been mostly awake (spontaneously), and another after it had been mostly asleep (50.0 ± 1.6 waking minutes in the preceding hour vs. 13.7 ± 2.2 min, respectively). We found that firing rates were significantly higher during the ON periods preceded by prolonged wakefulness compared to those preceded by consolidated sleep periods (Figure 6A, right panel). We then focused on daytime, when rats are predominantly asleep, and compared early with late sleep. As shown in Figure 6B, firing rates during ON periods were consistently higher in early NREM sleep and lower in late NREM sleep. Moreover, changes in firing rates during the ON periods of NREM sleep correlated positively with changes in NREM SWA (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Effects of sleep/waking history on firing rates.

(A) Top left: SWA time course and corresponding hypnogram during a ~3-hour interval during the night, centered on a ~40-min long waking bout in one representative rat. Bottom left: examples of NREM ON periods before and after consolidated waking. Right: Average firing rates within the ON periods (mean values + SEM, 115 neurons, n = 4 rats). Triangle: p<0.05. (B) Top left: SWA and corresponding hypnogram during a 6-hour interval starting at light onset in one representative rat. Bottom left: examples of ON periods in early (within the first hour after lights on) and late (~ 5–6 hours after lights on) sleep. Right: Average firing rates within the ON periods in early and late sleep (mean values + SEM, 125 neurons, n = 4 rats). Triangle: p<0.05. Note that since different data sets contributed to panels (A) and (B), absolute firing rates values cannot be compared directly. (C) Relationship between NREM SWA (0.5–4.0 Hz, % of 12-hour light period mean) and neuronal firing rates within the ON periods (% of 12-hour light period mean) computed for the four 3-hour intervals of the light period (n=7 rats, 1–5 days/rat). Line depicts linear regression (Pearson). (D) Mean firing rates computed for NREM (including ON and OFF periods, 162 neurons, n=7 rats), waking (106 neurons, n=7 rats) and REM (136 neurons, n=7 rats) sleep in conditions of high and low sleep pressure. Triangles: p<0.05. To compare firing rates during waking, 4-sec epochs in high and low sleep pressure condition were equated based on EMG values. (E) Firing rates within the ON periods in NREM sleep before and after waking episodes lasting 5–25 min (n=7 rats). All waking episodes were subdivided into those without short sleep attempts (0% sleep) and those containing ~ 1–10% of NREM sleep. Mean values are shown as % of the mean between the bars. Triangle: p<0.05. (F) Firing rates in waking before and after sleep periods lasting <=60 min and consisting of > 70% of NREM sleep. Firing rates are shown separately for short sleep periods < 15 min and those longer than 15 min. Mean values are shown as % of the mean between the bars. Triangles: p<=0.05.

Are these changes in firing rate occurring exclusively during NREM sleep, or are they found in all behavioral states? As shown in Figure 6D, during episodes of wakefulness and REM sleep mean firing rates were also higher under high sleep pressure and lower under low sleep pressure. These changes in firing rates were even more remarkable if one considers that rats are highly polyphasic and, especially during the dark period, the spontaneous sleep/wake cycle is fragmented. To further test whether even short wake and sleep episodes lead to changes in neuronal activity, we selected short (5–25 min) continuous wake episodes preceded and followed by sleep, or sleep periods (≤ 60 min) consisting mainly of NREM sleep and preceded and followed by waking, and compared firing rates at the beginning and end of these episodes. We found that the wake-related increase in firing rate was present even after short waking bouts, but only if waking was not interrupted by sleep attempts (Figure 6E), suggesting that the quality of waking is an important determinant of neuronal activity during subsequent sleep. At the same time, even short (<15 min) “power naps” led to a significant decrease in firing rates, although the effect was more pronounced after longer sleep periods (Figure 6F).

Though multielectrode arrays are biased towards picking up activity from larger and closest cells, we could detect spikes from all three major neuronal subtypes: putative regular spiking (RS), intrinsically bursting (IB), and fast-spiking (FS) neurons (Figure 7A, Figure S3). Consistent with previous studies (Bartho et al., 2004; McCormick et al., 1985; Steriade et al., 1993c), these three types were subdivided into two groups based on the width of the action potential at ½ amplitude (Figure 7B–D). The group with narrow spikes (< 0.25ms) was characterized by low spike amplitude, higher firing rates and shorter ISIs, and therefore likely includes mostly putative inhibitory neurons (FS cells). The group with broad spikes (>0.25ms) was characterized instead by high spike amplitude, longer ISIs or spontaneous bursts, overall lower rate of discharge, and likely includes mostly pyramidal excitatory neurons (RS and IB cells). Computing the firing rates for the high and low sleep pressure condition separately for neurons with narrow and broad spikes revealed that they were similarly affected by the sleep/wake history (Figure 7E). Altogether, these findings indicate that cortical mean firing rates change as a function of sleep homeostasis, and they do so across all three behavioral states.

Figure 7. Effects of sleep-wake history on the firing rates of different neuronal subtypes.

(A) Interspike intervals (ISIs) distribution for three representative neurons belonging to three major firing phenotypes, putative fast spiking (FS), putative regular spiking (RS) and putative intrinsically bursting (IB). Insets show the shortest ISIs (<20 ms). Note the different scales on the y-axes. (B) Distribution of individual neurons as a function of their spike width at ½ amplitude. All units were subdivided into two categories with narrow spikes and broad spikes (shaded areas). (C) Average spike waveforms corresponding to the two categories of narrow spike (<0.25 ms) and broad spike (>0.25 ms) units. (D) Interspike intervals (ISIs) distribution for neurons characterized by short action potential (<0.25 ms, putative inhibitory neurons, 45 neurons, n=6 rats) and for neurons characterized by long action potential (>0.25 ms, putative excitatory neurons, 38 neurons, n=6 rats). Mean values ±SEM. Inset highlights the differences between the two neuronal subtypes for the short ISIs (<20 ms). (E) Mean values (n=6–7 rats/group) of firing rates in NREM sleep, REM sleep and waking computed separately for the narrow spike and broad spike units for high and low sleep pressure conditions. Firing rates are shown as absolute values (top) and as % of the mean between the bars (bottom). Note the different scales on the y-axes. Triangles: p<0.05.

Increased sleep pressure after sleep deprivation is associated with changes in neuronal activity patterns and elevated firing rates

EEG SWA is a marker of homeostatic sleep pressure, being proportional to the time spent awake, and is largely unaffected by circadian time (Dijk et al., 1987). The changes in neuronal firing patterns and firing rates reported here appear to follow SWA, suggesting that they are homeostatic. To test the homeostatic nature of these effects and experimentally disentangle them from circadian effects, we performed 4 hours of sleep deprivation starting at light onset, and measured cortical activity during the subsequent recovery sleep. Sleep deprivation was successful (rats were awake 93% of the time) and, as expected, recovery sleep was associated with elevated SWA compared to the corresponding time of day during baseline (SWA in the first 2-hour interval of recovery: 195.6 ± 16.2 vs. 103.2 ± 4.0, % of baseline mean, p<0.01, Figure 8A). During sleep deprivation neuronal firing rates showed a progressive increase up to the third hour, and then reached a plateau during the fourth hour (Figure 8B). To investigate in more detail which changes in neuronal activity patterns could account for this time course we quantified the number of long (>50 ms) and short (<20ms) interspike intervals (ISIs) for each individual neuron. Both measures increased progressively, suggesting that while neurons showed increased firing as reflected in the short ISIs (>40% increase), this increase was counteracted at the end of sleep deprivation by an increased number of neuronal silent periods (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Effects of sleep deprivation on cortical firing.

(A) SWA time course during the light period in baseline and after sleep deprivation (SDep) in one representative rat. Hypnogram from the same animal is shown below. (B) Time course of neuronal firing rates, and the number of long (>50 ms) and short (<20 ms) interspike intervals (ISIs) in waking during SDep (50 neurons, n= 5 rats). Mean values ± SEM shown as % of the value during the first hour of SDep. Asterisks: p<0.05. Inset: average firing rates during the first and fourth hour of SDep after equating the 4-sec epochs based on EMG values (mean values shown as % of the mean between the two bars). Triangle: p<0.05. (C) Number and duration of ON and OFF periods during the first hour of recovery after SDep (Rec), and corresponding time interval during baseline (BSL). Values are mean + SEM (n = 5 rats). Triangles, p<0.05. (D) Representative examples of ON periods (boxed) during baseline and recovery sleep in one rat. (E) Average firing rates within the ON periods during the first 1-hour interval after SDep and the corresponding time interval during baseline in NREM sleep (62 neurons, n=7 rats) and REM sleep (49 neurons, n =7 rats).

After sleep deprivation the duration of ON periods during early recovery sleep was ~40% lower than at baseline, whereas both number and duration of OFF periods increased (Figure 8C). In all rats the decline of these variables towards baseline values in the course of recovery sleep was correlated (p<0.05) with the decrease in SWA. Despite the much shorter duration of ON periods after sleep deprivation, it was still possible to identify ON periods that were long enough to reveal intense neuronal firing (Figure 8D). Computation of firing rates during ON periods revealed significantly higher activity (by ~ 20%) in the first hour after sleep deprivation relative to the corresponding baseline interval (same circadian time, Figure 8E). Neuronal firing rates during early recovery were also affected in waking and REM sleep. Thus, compared to the corresponding baseline interval, in the first hour after sleep deprivation firing rates were increased by 64.4±21.9 % in waking (p<0.01), and by 33.3±10.9% in REM sleep (p<0.01; Figure 8E). Of note, neuronal firing rates in early recovery changed also with respect to pre-sleep deprivation levels: in NREM sleep firing rates increased by 34.0±16.3% (p<0.05), whereas in REM sleep the increase reached 53.7±30.3% (p<0.05). During the initial recovery NREM sleep was characterized by significantly shorter ON periods as compared to pre-sleep deprivation levels (− 37.3±10.3%, p<0.05), whereas both the duration of the OFF periods and the number of ON and OFF periods were significantly increased (by 32.0±11.8, 81.1±33.5 and 132.7±45.7%, respectively, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Since the beginning of unit recordings in vivo, many studies have investigated changes in neuronal firing across behavioral states. Early reports found that, throughout the cerebral cortex, neurons often show a burst-pause pattern in NREM sleep, compared to tonic firing in wakefulness and REM sleep (Burns et al., 1979; Calvet et al., 1973; Desiraju, 1972; Hobson and McCarley, 1971; Murata and Kameda, 1963; Noda and Adey, 1970; Noda and Adey, 1973; Verzeano and Negishi, 1960). Later, intracellular recordings in vivo showed that during NREM sleep virtually all cortical neurons alternate between a depolarized up state, during which they are spontaneously firing, and a hyperpolarized, silent down state (Steriade et al., 2001). This so-called slow oscillation (<1 Hz) between up and down states occurs more or less synchronously across many neurons (Steriade et al., 1993b), leading to an alternation between periods of multiunit activity and silence in extracellular recordings (Steriade et al., 2001), and to negative peaks (slow waves) in the sleep EEG. By contrast, wakefulness and REM sleep are characterized by a sustained depolarization and tonic firing, and are associated with an absence of EEG slow waves.

So far, however, no study had asked whether cortical neuronal firing patterns change not just depending on whether one is awake or asleep, but rather depending on how long one has been awake or asleep. This question is important because sleep is homeostatically regulated: the longer one has been awake, the more one needs to sleep; conversely, sleep need can only be reduced by having slept (Achermann and Borbely, 2003). This homeostatic regulation is a main reason to think that sleep may serve an essential function for brain cells (Cirelli and Tononi, 2008). Therefore, knowing whether firing patterns change depending on how long the brain has been awake or asleep might shed light on the need for sleep at the cellular level. By recording continuously EEG and cortical unit activity in freely behaving rats, we found that neuronal firing rates, firing synchrony, and distribution of ON and OFF periods do indeed change as a function of sleep homeostasis.

Homeostatic changes in neuronal firing rates

A key finding of this study is that spontaneous firing rates of cortical neurons increase in a systematic manner with the duration of preceding wakefulness, and decrease with the duration of preceding sleep. These changes in firing rate, which were correlated with changes in sleep homeostasis, were evident across wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep, suggesting an overall shift in neuronal excitability independent of the current behavioral state. It is generally assumed that average firing rates ought to be relatively stable thanks to the tight balance between excitation and inhibition (Haider et al., 2006). For example, it has been shown that a dynamic equilibrium of excitation and inhibition keeps spontaneous network activity within physiological ranges and prevents paroxysmal activity (McCormick and Contreras, 2001). Moreover, the tight balance between excitation and inhibition is maintained during the middle portion of sleep up states, although excitation is briefly uncoupled from inhibition at the up-down and down-up transitions (Haider et al., 2006). Functionally, firing rates should be regulated to avoid i) increased energy requirements (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001; Laughlin et al., 1998); ii) neurotoxicity (Choi, 1988); iii) risk of seizures (McCormick and Contreras, 2001). As shown here, however, merely staying awake leads to a progressive increase in firing rates. Consistent with this finding, i) in mice cortical metabolic rates increase after a comparable period (4 hours) of wakefulness, and decrease with sleep (Vyazovskiy et al., 2008b); ii) in rats the levels of glutamate in the cortical extrasynaptic space increase progressively during wakefulness and decrease during NREM sleep (Dash et al., 2009); iii) sleep deprivation leads to increased cortical excitability, resulting in lowered threshold for epileptic activity (Badawy et al., 2006; Civardi et al., 2001; Rowan et al., 1982; Scalise et al., 2006). Thus, it would seem that, not withstanding various mechanisms promoting stable activity levels, staying awake leads to a progressive increase in firing rates of cortical neurons, which is counterbalanced by staying asleep. The changes in firing rates that we observed between the high and low sleep pressure conditions were usually in the range of a few action potentials per neuron per second. While an increase in 1–2 Hz in the firing rate of individual neurons may be modest in relation to specific stimuli or behaviors, a generalized increase of spontaneous firing rates across the entire neuronal population and across all conditions is likely significant as it may raise the already high metabolic costs of brain activity (Laughlin et al., 1998). Specifically, it has been estimated that an increase in activity of just 1 action potential/cortical neuron/s can increase glucose consumption by 21 μmol/100g grey matter/min (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001; Sokoloff et al., 1977). This is a substantial change if one considers that the total average glucose consumption in the awake rodent cortex ranges from 107 to 162 μmol/100g/min (Sokoloff et al., 1977).

Increased neuronal firing rates after spontaneous waking episodes suggested that a further increase could occur during extended wakefulness, a possibility that we tested by sleep depriving rats for 4 hours starting at light onset. In most neurons firing rates increased continuously for the first 3 hours and showed no further significant change in the last hour, most likely due to an increased number of neuronal silent periods. These results are consistent with the observation that cortical glutamate levels no longer increase after a few hours of continuous waking in the rat (Dash et al., 2009). We also found that prolonging wakefulness beyond the usual bedtime led to a further increase in firing rates during recovery sleep. By contrast, when animals were allowed to sleep, firing rates decreased progressively in all behavioral states. Since the comparison between sleep deprivation and sleep was done at the same time of day, changes in mean firing rates must be related to the time the animal spent awake or asleep, rather than to differences in circadian phase. Moreover, these data suggest that under physiological conditions sleep may be important, perhaps even necessary, for returning neuronal activity to a lower, sustainable level after periods of wakefulness. Of note, firing rates decreased from the high to the low sleep pressure condition in neurons with both narrow and broad action potentials. Since these two categories are characterized by high and low mean firing rates, and likely correspond to inhibitory and excitatory neurons, respectively, the data suggest that the balance between excitation and inhibition is generally maintained at different levels of physiological sleep pressure.

For the interpretation of the present results it is important to assess the stability of unit recordings over several hours or even days, since changes in the number of spikes could be due to a progressive increase in the number of active units rather than to an increased firing of the same units. As shown in Figure S2, however, waveform analysis (Williams et al., 1999) indicates that the shape of the spikes of individual sorted units remained stable over several hours. Furthermore, while the number of recorded units may change progressively over time due to electrode deterioration and other technical factors, we observed several cycles of systematic increases and decreases of firing with time awake and asleep, respectively. These cycles repeated over several sleep-wake episodes in the course of the same day, or even across different days, and were strongly correlated with SWA. Therefore, our results likely cannot be explained by recording instability.

Homeostatic changes in neuronal synchronization and relationship to EEG slow wave activity

A second finding was that changes in mean firing rate were accompanied by changes in neuronal synchronization during the transition between ON and OFF periods. During sleep episodes following prolonged bouts of wakefulness (early sleep), individual neurons stopped or resumed firing in near synchrony with the rest of the population. By contrast, during sleep episodes following prolonged bouts of NREM sleep (late sleep), the time of entry into ON and OFF periods was much less synchronous.

In turn, changes in synchrony were accompanied by changes in the duration of population ON and OFF periods. During early sleep, when most neurons were active or silent synchronously, ON periods were short and frequent. During late sleep, the periods of activity and inactivity of individual neurons became progressively less synchronized. Indeed, it was apparent that in late sleep some neurons were unresponsive to the population “drive” and remained in the ON mode while the rest of the population was already silent, or remained silent when most other neurons generated spikes. Consequently, population ON periods became longer and less frequently interrupted by population OFF periods. Without chronic intracellular recordings, it is difficult to know whether the duration of the individual neurons’ up state also increases with decreasing sleep pressure, though our computer simulations suggest that this may be the case (Esser et al., 2007).

Finally, we found that changes in neuronal synchrony were linked to changes in the EEG slow waves. Specifically, high firing synchrony was associated with steep slopes of simultaneously occurring EEG slow waves, whereas low synchrony was associated with decreased slopes. These observations provide direct in vivo evidence that EEG slow wave slopes are determined by the rate of recruitment and decruitment of cortical neurons into the slow oscillation, as predicted by modeling work (Esser et al., 2007). Furthermore, changes in the number and duration of ON and OFF periods were also correlated with the decrease in SWA in the course of sleep, consistent with the notion that large and steep EEG slow waves should reflect the near-synchronous transitions between up and down state in large populations of cortical neurons, whereas reduced synchrony should be associated with smaller and shallower waves (Burns et al., 1979; Calvet et al., 1973; Contreras and Steriade, 1995; Ji and Wilson, 2007; Luczak et al., 2007; Molle et al., 2006; Mukovski et al., 2006; Murata and Kameda, 1963; Noda and Adey, 1973; Steriade et al., 1993c; Steriade et al., 2001). While slow wave slopes are likely a function of neuronal synchrony, the mechanisms underlying the changes in slow wave amplitude are less clear, and may be related to the duration of the corresponding periods of neuronal silence (e.g. Figure 3). We found that neuronal synchrony had less pronounced effects on the slope and amplitude of the slow wave corresponding to the OFF-ON transition. Such data are consistent with earlier observations that the second segment of the slow wave is characterized by steeper slope, and is less affected by sleep-wake history, compared to the first segment (Vyazovskiy et al., 2009; Vyazovskiy et al., 2007). Moreover, in anesthetized ferrets the transition from down to up state occurs at a significantly faster rate and more synchronously than the transition from activity to silence (Haider et al., 2006).

As mentioned in the Introduction, EEG slow waves are a well-established marker of sleep need. In general, the longer one has been awake, the higher the amount of SWA in the sleep EEG; conversely, SWA decreases progressively in the course of sleep (Achermann and Borbely, 2003). However, the cellular correlates of slow wave homeostasis are largely unknown. The present results establish that sleep-wake history is reflected at the level of cortical neuronal activity in terms of both firing rates and firing synchrony. Moreover, there is a tight link between changes in neuronal firing on one hand, and homeostatic changes of EEG SWA on the other. Thus, our findings suggest that changes in neuronal firing and synchrony may represent a cellular counterpart of the homeostatic regulation of sleep, raising the possibility that they may have physiological significance.

Possible mechanisms underlying homeostatic changes in firing rate and synchrony

Why would cortical firing rates and neuronal synchrony increase with the duration of wakefulness and decrease with the duration of sleep? Mechanisms that could be responsible for compensatory changes in firing rates include homeostasis of intrinsic excitability, such as changes in intrinsic conductances (van Welie et al., 2004), as well as global synaptic scaling (Turrigiano, 1999). However, the changes in firing rate observed in vivo in our experiments may be too small to trigger the homeostatic changes observed in vitro or after non-physiologic manipulations during development (Desai et al., 2002).

Another possibility is that changes in neuronal firing and synchrony reflect a progressive, net increase in the strength of cortico-cortical connections during wakefulness, followed by a gradual net decrease during sleep (Tononi and Cirelli, 2006), as suggested by some recent studies (Bellina et al., 2008; Gilestro et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2007; Vyazovskiy et al., 2008a). Indeed, in a large-scale model of the corticothalamic system, a net decrease in the efficacy of excitatory cortico-cortical connections can lead, at the cellular level, to: i) a decrease in mean firing rates both when the model was run in sleep mode and in waking mode; ii) a decrease in population synchrony at the ON-OFF and OFF-ON transitions in sleep mode; iii) a decrease in the number of ON (and OFF) periods and an increase in their duration (Figure S5). At the EEG level, consistent with previous work (Esser et al., 2007), it led to: iv) a decrease in the slope of sleep slow waves; and v) a decrease in SWA. Highly synchronous burst firing during the ON periods of early NREM sleep, the alternation of depolarization and hyperpolarization at around 1 Hz, and the neuromodulatory milieu of sleep may help restore synaptic strength (Czarnecki et al., 2007; Lubenov and Siapas, 2008; Seol et al., 2007). On the other hand, these mechanisms could act to some extent also during wakefulness, or on a fast time scale that does not require sustained periods of NREM sleep. Moreover, fast-acting processes of synaptic depression and rebound, operating differentially in excitatory and inhibitory synapses (Galarreta and Hestrin, 1998), could help maintain a balance of synaptic strength without requiring sleep-dependent downscaling. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether and how sleep may affect synaptic homeostasis during development, when sleep is especially abundant. For example, studies in kittens show that the first few hours of sleep immediately following monocular deprivation are important both to maintain the post-synaptic reduction in evoked responses to the deprived eye and to potentiate the response to the non-deprived eye (Aton et al., 2009; Dadvand et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2001). However, whether the overall effect of sleep after monocular sleep deprivation is a net increase, a net decrease, or no change in synaptic strength, remains unclear, and what might happen during development under more physiological conditions remains unknown.

Finally, changes in the levels of arousal-promoting neuromodulators could in principle account for many of our findings (Figure S5). Neuromodulators such as acetylcholine not only can switch the cortex from a sleep to a wake mode of firing (Steriade et al., 1993a), but can affect both intrinsic and synaptic conductances (Gil et al., 1997; Marder and Thirumalai, 2002). Thus, progressive changes in neuromodulatory levels between early and late sleep may alter the firing patterns of cortical neurons, and our previous computer simulations showed that both lowering synaptic strength and increasing levels of arousal-promoting neuromodulators can decrease SWA and the amplitude of slow waves (Esser et al., 2007). It should be mentioned, however, that the current in vivo experiments showed that changes in mean firing rates as a function of sleep-wake history occurred in all behavioral states, in spite of clear-cut differences in neuromodulatory levels between sleep and waking (Jones, 2005).

Changes in firing after learning tasks or electrical stimulation have been investigated in brain regions outside the cortex, such as the hippocampal formation. Hippocampal recordings have revealed only weak, non-significant increases in global firing rates during sleep after exposure to a novel environment (Hirase et al., 2001; Kudrimoti et al., 1999) or after electrically-induced LTP (Dragoi et al., 2003) relative to sleep before, suggesting that hippocampal global firing rates are stable across behavioral states and learning conditions (Buzsaki et al., 2007; Karlsson and Frank, 2008; Pavlides and Winson, 1989). However, it is not clear whether the hippocampus is involved in sleep homeostasis, slow oscillations are absent in several hippocampal subregions (Isomura et al., 2006), and the balance of excitation and inhibition may be regulated differently (Buzsaki et al., 2007). Moreover, in most of these studies the waking experience was short-lasting.

In future studies, it will be important to simultaneously record EEG, neural activity, and the levels of extracellular neuromodulators. Moreover, one should investigate whether the homeostatic changes in firing patterns observed in barrel cortex can be generalized to other cortical areas, including prefrontal areas where slow wave homeostasis is most pronounced (Cajochen et al., 1999; Werth et al., 1996a), and in subcortical areas, including the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus that controls the 24-h distribution of sleep and waking (Deboer et al., 2003). Also, one would want to know how firing patterns change after tasks that activate circumscribed cortical regions, as suggested by the local regulation of sleep SWA (Huber et al., 2004; Vyazovskiy and Tobler, 2008). Moreover, the current findings raise the question of whether the overall increase in firing rate observed across waking reflects a generalized phenomenon or is mainly driven by changes in a subset of neurons, for instance those with sustained firing across most of wake and not those with episodic firing, or those with the highest firing rates, or those exhibiting specific firing patterns (tonic or burst firing). It will also be important to clarify whether firing associated with some behavioral activities, perhaps those leading to experience-dependent plasticity and to the release of neuromodulators, contribute more than others to the overall increase in firing rate during the physiological waking period. If the present findings can indeed be generalized to other cortical regions, they would suggest that sleep may serve, among other functions, to maintain neuronal firing rates at a sustainable level.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Surgery and multiunit activity recording

Male WKY rats were implanted in the left barrel cortex (n=6) or in the frontal cortex (n=1) with 16-ch (2×8) polyimide-insulated tungsten microwire arrays, as detailed in the Supplemental Data. After surgery all rats were housed individually in transparent Plexiglas cages. Lighting and temperature were kept constant (LD 12:12, light on at 10am, 23±1°C; food and water available ad libitum and replaced daily at 10am). About a week was allowed for recovery after surgery, and experiments were started only after the sleep/waking cycle had fully normalized. Animal protocols followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Signal processing and analysis

Data acquisition and online spike sorting were performed with the Multichannel Neurophysiology Recording and Stimulation System (Tucker-Davis Technologies Inc., TDT), as detailed in the Supplemental Data. Spike data were collected continuously (25 kHz, 300–5 kHz), concomitantly with the local field potentials (LFPs) from the same electrodes (256 Hz) and surface EEG (256 Hz). Amplitude thresholds for online spike detection were set manually based on visual and auditory control and allowed only crossings of spikes with signal-to-noise ratio of at least 2 (Figure S1,S2). EEG power spectra were computed by a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) routine for 4-sec epochs (0.25 Hz resolution). For staging, signals were loaded with custom-made Matlab programs using standard TDT routines, and subsequently transformed into the EDF (European Data Format) with Neurotraces software. Sleep stages were scored off-line by visual inspection of 4-sec epochs (SleepSign, Kissei), where the EEG, LFP, EMG and spike activity was displayed. Vigilance states could always be determined.

Experimental design

Recordings were performed continuously for 2–3 weeks starting from day 5 after surgery, when rats appeared normal and their sleep-wake cycle had normalized. A total of 4–7 animals contributed to different experiments and data analyses. To assure that the homeostatic changes were consistent across days, at least one 12-hour light period and one 12-hour dark period (range: 1–7 days) were selected per animal based on signal stability, and analyzed separately. After 2–3 stable baselines, one or two 4-hour sleep deprivation (SDep) experiments were performed in each animal (at least 5 days apart), each followed by an undisturbed recovery period, as detailed in the Supplemental Data. Analysis of the firing rates is detailed in the Supplemental Data.

Data processing and analysis and spike sorting

Details are given in the Supplemental Data.

Histological verification

Upon completion of the experiments the position of the arrays was verified by histology in all animals. In all cases the deep row of the array was located within layer V, whereas the superficial row was in layers II-III.

Computer simulations

The large-scale computational model of the thalamocortical system is similar to the one previously used (Esser et al., 2007), and is described in detail in the Supplemental Data. Synaptic strength was varied in a subset (33%) of corticocortical AMPA connections. Several levels of strength decrease were tested (Details in Supplemental data). Data shown refer to a 25% decrease, which was found to be sufficient to induce changes in neuronal activity similar to those observed in in vivo experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH P20 MH077967 (CC), NIH Director’s Pioneer award (GT) and AFOSR FA9550-08-1-0244 (GT). We thank Tom Richner and Dr Silvestro Micera for help with data analysis, Aaron Nelson for help with the experiments, Dr Yuval Nir for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr Lisa Krugner-Higby for advice about surgical procedures.

Footnotes

COI statement: All authors indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achermann P, Borbely AA. Mathematical models of sleep regulation. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s683–693. doi: 10.2741/1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amzica F, Steriade M. Electrophysiological correlates of sleep delta waves. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;107:69–83. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(98)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton SJ, Seibt J, Dumoulin M, Jha SK, Steinmetz N, Coleman T, Naidoo N, Frank MG. Mechanisms of sleep-dependent consolidation of cortical plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61:454–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy RA, Curatolo JM, Newton M, Berkovic SF, Macdonell RA. Sleep deprivation increases cortical excitability in epilepsy: syndrome-specific effects. Neurology. 2006;67:1018–1022. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237392.64230.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartho P, Hirase H, Monconduit L, Zugaro M, Harris KD, Buzsaki G. Characterization of neocortical principal cells and interneurons by network interactions and extracellular features. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:600–608. doi: 10.1152/jn.01170.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Model of thalamocortical slow-wave sleep oscillations and transitions to activated States. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8691–8704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellina V, Huber R, Rosanova M, Mariotti M, Tononi G, Massimini M. Cortical excitability and sleep homeostasis in humans: a TMS/hd-EEG study. Journal of Sleep Research. 2008;17:39. [Google Scholar]

- Burns BD, Stean JP, Webb AC. The effects of sleep on neurons in isolated cerebral cortex. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1979;206:281–291. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Kaila K, Raichle M. Inhibition and brain work. Neuron. 2007;56:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajochen C, Foy R, Dijk DJ. Frontal predominance of a relative increase in sleep delta and theta EEG activity after sleep loss in humans. Sleep Res Online. 1999;2:65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvet J, Fourment A, Thiefry M. Electrical activity in neocortical projection and association areas during slow wave sleep. Brain Res. 1973;52:173–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron. 1988;1:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, Tononi G. Is sleep essential? PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civardi C, Boccagni C, Vicentini R, Bolamperti L, Tarletti R, Varrasi C, Monaco F, Cantello R. Cortical excitability and sleep deprivation: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:809–812. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Steriade M. Cellular basis of EEG slow rhythms: a study of dynamic corticothalamic relationships. J Neurosci. 1995;15:604–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00604.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki A, Birtoli B, Ulrich D. Cellular mechanisms of burst firing-mediated long-term depression in rat neocortical pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2007;578:471–479. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand L, Stryker MP, Frank MG. Sleep does not enhance the recovery of deprived eye responses in developing visual cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;143:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash MB, Douglas CL, Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Tononi G. Long-term homeostasis of extracellular glutamate in the rat cerebral cortex across sleep and waking states. J Neurosci. 2009;29:620–629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5486-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboer T, Vansteensel MJ, Detari L, Meijer JH. Sleep states alter activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nn1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju T. Discharge properties of neurons of the parietal association cortex during states of sleep and wakefulness in the monkey. Brain Res. 1972;47:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Contreras D, Steriade M. Spatiotemporal analysis of local field potentials and unit discharges in cat cerebral cortex during natural wake and sleep states. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4595–4608. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04595.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Beersma DG, Daan S. EEG power density during nap sleep: reflection of an hourglass measuring the duration of prior wakefulness. J Biol Rhythms. 1987;2:207–219. doi: 10.1177/074873048700200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi G, Harris KD, Buzsaki G. Place representation within hippocampal networks is modified by long-term potentiation. Neuron. 2003;39:843–853. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser SK, Hill SL, Tononi G. Sleep homeostasis and cortical synchronization: I. Modeling the effects of synaptic strength on sleep slow waves. Sleep. 2007;30:1617–1630. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraguna U, Vyazovskiy VV, Nelson AB, Tononi G, Cirelli C. A causal role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the homeostatic regulation of sleep. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4088–4095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5510-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Issa NP, Stryker MP. Sleep enhances plasticity in the developing visual cortex. Neuron. 2001;30:275–287. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Frequency-dependent synaptic depression and the balance of excitation and inhibition in the neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:587–594. doi: 10.1038/2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19:679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilestro GF, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Widespread changes in synaptic markers as a function of sleep and wakefulness in Drosophila. Science. 2009;324:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1166673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, McCormick DA. Neocortical network activity in vivo is generated through a dynamic balance of excitation and inhibition. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4535–4545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5297-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Czurko A, Csicsvari J, Buzsaki G. Firing rates of hippocampal neurons are preserved during subsequent sleep episodes and modified by novel awake experience. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9386–9390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161274398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson JA, McCarley RW. Cortical unit activity in sleep and waking. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1971;30:97–112. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(71)90271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Esser SK, Ferrarelli F, Massimini M, Peterson MJ, Tononi G. TMS-induced cortical potentiation during wakefulness locally increases slow wave activity during sleep. PLoS ONE. 2007a;2:e276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Ferrarelli F, Riedner BA, Peterson MJ, Tononi G. Arm immobilization causes cortical plastic changes and locally decreases sleep slow wave activity. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1169–1176. doi: 10.1038/nn1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G. Local sleep and learning. Nature. 2004;430:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Exploratory behavior, cortical BDNF expression, and sleep homeostasis. Sleep. 2007b;30:129–139. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomura Y, Sirota A, Ozen S, Montgomery S, Mizuseki K, Henze DA, Buzsaki G. Integration and Segregation of Activity in Entorhinal-Hippocampal Subregions by Neocortical Slow Oscillations. Neuron. 2006;52:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Wilson MA. Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson MP, Frank LM. Network dynamics underlying the formation of sparse, informative representations in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14271–14281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4261-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattler H, Dijk DJ, Borbely AA. Effect of unilateral somatosensory stimulation prior to sleep on the sleep EEG in humans. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1994.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudrimoti HS, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal cell assemblies: effects of behavioral state, experience, and EEG dynamics. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4090–4101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04090.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin SB, de Ruyter van Steveninck RR, Anderson JC. The metabolic cost of neural information. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:36–41. doi: 10.1038/236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubenov EV, Siapas AG. Decoupling through synchrony in neuronal circuits with propagation delays. Neuron. 2008;58:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak A, Bartho P, Marguet SL, Buzsaki G, Harris KD. Sequential structure of neocortical spontaneous activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:347–352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605643104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Thirumalai V. Cellular, synaptic and network effects of neuromodulation. Neural Netw. 2002;15:479–493. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini M, Huber R, Ferrarelli F, Hill S, Tononi G. The sleep slow oscillation as a traveling wave. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6862–6870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1318-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Connors BW, Lighthall JW, Prince DA. Comparative electrophysiology of pyramidal and sparsely spiny stellate neurons of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:782–806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Contreras D. On the cellular and network bases of epileptic seizures. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:815–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle M, Yeshenko O, Marshall L, Sara SJ, Born J. Hippocampal sharp wave-ripples linked to slow oscillations in rat slow-wave sleep. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:62–70. doi: 10.1152/jn.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukovski M, Chauvette S, Timofeev I, Volgushev M. Detection of Active and Silent States in Neocortical Neurons from the Field Potential Signal during Slow-Wave Sleep. Cereb Cortex. 2006 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Kameda K. The Activity of Single Cortical Neurones of Unrestrained Cats During Sleep and Wakefulness. Arch Ital Biol. 1963;101:306–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Adey WR. Firing of neuron pairs in cat association cortex during sleep and wakefulness. J Neurophysiol. 1970;33:672–684. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Adey WR. Neuronal activity in the association cortex of the cat during sleep, wakefulness and anesthesia. Brain Res. 1973;54:243–259. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleksenko AI, Mukhametov LM, Polyakova IG, Supin AY, Kovalzon VM. Unihemispheric sleep deprivation in bottlenose dolphins. J Sleep Res. 1992;1:40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlides C, Winson J. Influences of hippocampal place cell firing in the awake state on the activity of these cells during subsequent sleep episodes. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2907–2918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02907.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y, Liu ZW, Borok E, Rabenstein RL, Shanabrough M, Lu M, Picciotto MR, Horvath TL, Gao XB. Prolonged wakefulness induces experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in mouse hypocretin/orexin neurons. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:4022–4033. doi: 10.1172/JCI32829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedner BA, Vyazovskiy VV, Huber R, Massimini M, Esser S, Murphy M, Tononi G. Sleep homeostasis and cortical synchronization: III. A high-density EEG study of sleep slow waves in humans. Sleep. 2007;30:1643–1657. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan AJ, Veldhuisen RJ, Nagelkerke NJ. Comparative evaluation of sleep deprivation and sedated sleep EEGs as diagnostic aids in epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;54:357–364. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalise A, Desiato MT, Gigli GL, Romigi A, Tombini M, Marciani MG, Izzi F, Placidi F. Increasing cortical excitability: a possible explanation for the proconvulsant role of sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2006;29:1595–1598. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol GH, Ziburkus J, Huang S, Song L, Kim IT, Takamiya K, Huganir RL, Lee HK, Kirkwood A. Neuromodulators control the polarity of spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;55:919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Amzica F, Nunez A. Cholinergic and noradrenergic modulation of the slow (approximately 0.3 Hz) oscillation in neocortical cells. J Neurophysiol. 1993a;70:1385–1400. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Contreras D, Curro Dossi R, Nunez A. The slow (< 1 Hz) oscillation in reticular thalamic and thalamocortical neurons: scenario of sleep rhythm generation in interacting thalamic and neocortical networks. J Neurosci. 1993b;13:3284–3299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03284.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Nunez A, Amzica F. Intracellular analysis of relations between the slow (< 1 Hz) neocortical oscillation and other sleep rhythms of the electroencephalogram. J Neurosci. 1993c;13:3266–3283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03266.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Nunez A, Amzica F. A novel slow (< 1 Hz) oscillation of neocortical neurons in vivo: depolarizing and hyperpolarizing components. J Neurosci. 1993d;13:3252–3265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Timofeev I, Grenier F. Natural waking and sleep states: a view from inside neocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1969–1985. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler I, Borbely AA. Sleep EEG in the rat as a function of prior waking. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;64:74–76. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG. Homeostatic plasticity in neuronal networks: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Welie I, van Hooft JA, Wadman WJ. Homeostatic scaling of neuronal excitability by synaptic modulation of somatic hyperpolarization-activated Ih channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5123–5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzeano M, Negishi K. Neuronal activity in cortical and thalamic networks. J Gen Physiol. 1960;43(6 Suppl):177–195. doi: 10.1085/jgp.43.6.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Pfister-Genskow M, Faraguna U, Tononi G. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for net synaptic potentiation in wake and depression in sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2008a;11:200–208. doi: 10.1038/nn2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Tononi G, Tobler I. Cortical metabolic rates as measured by 2-deoxyglucose-uptake are increased after waking and decreased after sleep in mice. Brain Res Bull. 2008b;75:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Faraguna U, Cirelli C, Tononi G. Triggering slow waves during NREM sleep in the rat by intracortical electrical stimulation: effects of sleep/wake history and background activity. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1921–1931. doi: 10.1152/jn.91157.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Riedner BA, Cirelli C, Tononi G. Sleep homeostasis and cortical synchronization: II. A local field potential study of sleep slow waves in the rat. Sleep. 2007;30:1631–1642. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Ruijgrok G, Deboer T, Tobler I. Running wheel accessibility affects the regional electroencephalogram during sleep in mice. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:328–336. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Tobler I. Handedness leads to interhemispheric EEG asymmetry during sleep in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:969–975. doi: 10.1152/jn.01154.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth E, Achermann P, Borbely AA. Brain topography of the human sleep EEG: antero-posterior shifts of spectral power. Neuroreport. 1996a;8:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth E, Dijk DJ, Achermann P, Borbely AA. Dynamics of the sleep EEG after an early evening nap: experimental data and simulations. Am J Physiol. 1996b;271:R501–510. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.3.R501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JC, Rennaker RL, Kipke D. Stability of chronic multichannel neural recordings: Implications for a long-term neural interface. Neurocomputing. 1999;26–27:1069–1076. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.