Intermolecular, enantioselective allylic substitution with alcohols[1, 2] remains an undeveloped catalytic process. Few reports have been published that describe the intermolecular allylation of aliphatic alcohols with high yield and enantioselectivity,[3] and the most selective of these systems has required copper additives.[4] The large number of α chiral ethers and oxygen heterocycles in natural products and pharmaceutical candidates makes enantioselective routes to these materials important.

This transformation has been difficult because alcohols are poor nucleophiles for allylic substitution, and the high basicity of alkoxides can induce elimination processes and catalyst deactivation. Thus, phenoxides,[5–12] siloxides,[13] and hydroxylamines[14, 15] serve as nucleophiles for allylic substitution, but intermolecular additions of common alcohols have been limited.[10, 16] Tin,[17] boron,[18, 19] zinc,[20] and copper[4,21–23] alkoxides have been used with the idea of softening an oxygen nucleophile, but these additives complicate reaction procedures and have only led to high yields and high enantioselectivities for reactions of allylic esters with an iridium–phosphoramidite catalyst.[4]

Herein we report that primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols, as well as silanols, can participate directly in catalytic asymmetric allylic substitution in the presence of an alkali metal base. Reactions conducted with a metallacyclic iridium catalyst[24–33] form chiral, branched allylic ethers and silyl ethers in high yield and high enantioselectivity.[3] These results reveal convenient procedures for the use of alcohol nucleophiles, improve the scope and yield of the allylation of primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols, and include the use of a catalytic amount of an alkyne additive to suppress olefin isomerization that forms vinyl ether side products. More generally, these results show that alkali metal alkoxides in low concentrations can be competent nucleophiles for allylic substitution.

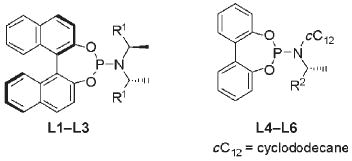

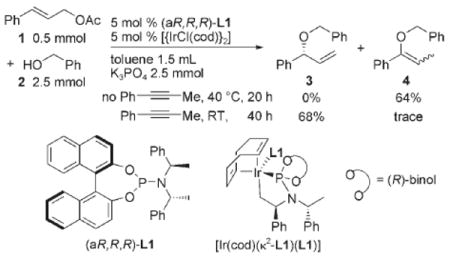

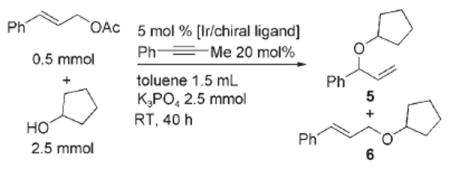

Our efforts to develop a direct allylation of alcohols began with studies of the reaction of cinnamyl acetate (1) with benzyl alcohol (2) in the presence of [{Ir(cod)Cl}2] (cod=1,5-cyclooctadiene) and phosporamidite L1 as precursors to the metallacyclic iridium catalyst [Ir(cod)(κ2L1)(L1)] in Equation (1). These reactions were conducted with potassium phosphate as base in toluene at 40 °C. Although C—O bond formation occurred, some of the desired allylic ether product 3 converted into the isomeric enol ether 4,[19,34,35] and low isolated yields of 3 were obtained [Eq. (1)]. After some experimentation, we found that the simple addition of a catalytic amount of an alkyne, such as 1-phenyl propyne, to the reaction medium suppressed this isomerization and led to high yields of the allylic ether product. For example, the reaction of cyclopentanol under these conditions afforded allylic ether 5 in 73% yield and 95% ee and 91:9 branched to linear ratio [Eq. (2), and entry 1 in Table 1]. Other internal alkynes, such as 1,2-diphenyl acetylene and 4-octyne, also suppressed the isomerization, but terminal alkynes did not. Although we have not yet studied the origin of this alkyne effect, we presume the alkyne poisons a separate isomerization catalyst present in small amounts.[36]

Table 1.

Effect of ligands on the allylic etherification.[a]

| L | Ligand | 5:6[b] | Yeld [%] | ee [%][c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | R1 = Ph | 91:9 | 73 | 95 |

| L2 | R1 = 2-anisyl | 95:5 | 62 | 99 |

| L3 | R1 = 1-Np | 87:13 | 64 | 91 |

| L4 | R2 = Ph | 90:10 | 64 | 91 |

| L5 | R2 = 2-anisyl | 82:8 | 59 | 89 |

| L6 | R2 = 1-Np | 88:12 | 60 | 71 |

All ratios of 5:6, isolated yields and ee or de values are averages from two independent runs.

Ratio of 5:6 determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Determined by HPLC.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Studies on the effect of solvent, base, and leaving group were also conducted. Reactions in toluene occurred in the highest yields. Reactions in the more polar solvents THF and 1,4-dioxane, as well as halogenated solvents, such as CH2Cl2, afforded the substitution product in low yields. Additionally, the use of Cs2CO3 as base resulted in the formation of significant amounts of a by-product resulting from transesterification of cinnamyl acetate with cyclopentanol and allylation of the resulting cinnamyl alcohol. Reactions conducted with NEt3 as base formed racemic products in 49% yield, presumably because NEt3 and the iridium precursor generate an active achiral catalyst. For high conversions, the use of highly powdered K3PO4 was important. Finally, the use of allylic carbonates as electrophile led to low yields of the desired ether, owing to cleavage of the carbonates to form the corresponding allylic alcohols and the alkyl carbonates derived from the alcohol nucleophile.

Table 1 summarizes results on the allylation of alcohols catalyzed by iridium complexes generated from several C2-symmetric and C1-symmetric phosphoramidites. The direct allylation of alcohols occurred with the highest regioselectivity and enantioselectivity in the presence of the catalyst generated from L2. However, ligand L1 is more accessible, and reactions catalyzed by the complex generated from L1 occurred in higher yield, and with acceptable regioselectivity and enantioselectivity. Reactions conducted with catalysts generated from L3–L5 occurred in only 59–64 yields with 89-91% enantioselectivity, and reactions conducted with L6 occurred with low enantioselectivity. With none of the catalysts was the enol ether detected in significant amounts when the reaction was conducted with added alkyne. Thus, further studies were conducted with the catalyst generated from L1 with added 1-phenyl-1-propyne.

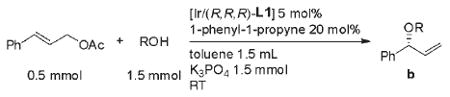

The scope of the alcohols that undergo allylation using cinnamyl acetate 1 as electrophile under optimized conditions is summarized in Table 2. The reaction of 1 with benzyl alcohol 2 gave the branched allylation product 3 without formation of enol ether 4 in 68% yield and 93% ee after 22 h (Table 2, entry 1). The representative primary aliphatic alcohol, n-hexanol formed the allyation product in 71% yield and 91% ee (Table 2, entry 2). The use of 5 equiv of n-hexanol slightly increased the yield and enantioselectivity (entry 3). Secondary alcohols besides cyclopentanol used for the studies in Table 1 also reacted. For example, cyclohexanol and N-Boc-protected piperadin-4-ol reacted in acceptable yield and high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity. α Chiral secondary alcohols, such as (S)-1-phenylethanol, also formed the allylation product in diasereomeric ratios d.r. 94:6 (88% de) and 95:5 (90% de) with the two enantiomers of the catalyst, although partial racemization of the alcohol (90 and 88% ee) was observed after the reaction. The high selectivities for both pairs of the alcohol and catalyst enantiomers allow this simple reaction to form bis α-chiral ethers with diasatereocontrol. tert-Butyldimethylsilanol also underwent the allylation chemistry in high yield and enantioselectivity. Enantioselective allylation of potassium triethylsiloxide with the cyclometalated iridium catalyst developed in our laboratory was reported by Carreira et al.,[13] but the current process bypasses the need to prepare the potassium siloxides. In all of these reactions with added 1-phenyl-1-propyne, enol ether sideproducts were not observed in significant amounts.

Table 2.

Scope of the allylic etherification with various alcohols.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | t [h] | b:l[b] | Yield [%], ee[c] or de |

| 1 | Bn | 22 | 99:1 | 68, 93% ee |

| 2 | n-hexyl | 40 | 99:1 | 71, 91% ee |

| 3[d] | n-hexyl | 20 | 84:16 | 77, 94% ee |

| 4[d] | cyclo-hexyl | 40 | 99:1 | 68, 93% ee |

| 5 | N-Boc-4-piperidinyl[e] | 50 | 99:1 | 66, 90% ee |

| 6 | (S)-1-phenylethanol | 80 | 99:1 | 67, 88% de[f] |

| 7[g] | (S)-1-phenylethanol | 40 | 99:1 | 63, 90% de |

| 8 | TBDMS[h] | 40 | 98:2 | 85, 98% ee |

All times, ratios of b:l, isolated yields and ee or de values are averages from two independent runs.

Ratio of b:l determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Determined by HPLC.

Alcohols (2.5 mmol) and K3PO4 (2.5 mmol) were used.

Boc=tert-butoxycarbonyl.

d.r. 94:6.

(S,S,S)-L1 was used; d.r.=95:5.

TBDMS=tert-butyldimethylsilyl.

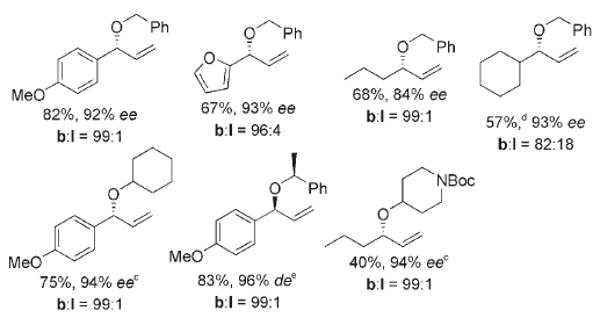

The scope of the reactions of a variety of allylic acetates with different alcohols is summarized in Scheme 1 and Equation (3). For all but one these reactions, the branched-to-linear ratios were higher than 96:4 and, with one exception, enantioselectivities were at least 92% ee. Aromatic allylic acetates containing anisyl and furyl groups on the aryl ring gave the corresponding branched allylic ethers in high yields. Not only aromatic but also purely aliphatic allylic carbonates reacted to give the substitution products in acceptable yields with good to excellent ee values and branched site selectivity. The reactions of aliphatic allylic acetates with the secondary alcohol N-(Boc)piperidinol occurred with high enantioselectivity and site selectivity, but the yield was modest.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of various combinations of allyl acetates and alcohols. Boc=tert-butoxycarbonyl. [a] All ratios of b:l, isolated yields and ee or de values are averages from two independent runs and ee values are determined by HPLC. [b] Ratio of b:l determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. [c] Alcohols (2.5 mmol) and K3PO4 (2.5 mmol). [d] Isolated yield of the combined regioisomers of b:l. [e] d.r.=98:2; (S,S,S)-L1 was used.

|

(3) |

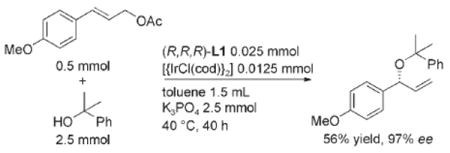

In addition to simplifying reactions of primary and secondary alcohols, these conditions led to the first allylation of a tertiary alcohol to form substitution products with high enantioselectivity. The iridium-catalyzed reaction of 4-methoxycinnamyl acetate with 2-phenyl-2-propanol gave the substitution product in 56% yield with excellent enantioselectivity at 40°C. Previous reactions of tertiary alkoxides with copper additives formed the substitution product in only 63% ee.[4]

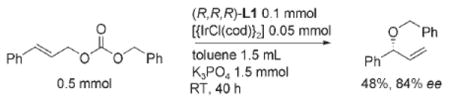

We also briefly investigated decarboxylative etherification.[37–43] This reaction [Eq. (4)] formed the allylic ether in 84% ee. Although this process required high catalyst loadings and occurred in moderate yield, it constitutes the first asymmetric decarboxylative allylation of O-nucleophiles.

|

(4) |

In summary, we have demonstrated that asymmetric allylic etherification can be conducted using allyl acetates and the combination of alcohols and base as nucleophile. Important in obtaining high yields of the substitution product, alkynes were shown to prevent isomerization of the allylic ether to the corresponding vinyl ether. The system reported here constitutes the most general current method for asymmetric allylic etherification using alcohols, including the first asymmetric allylation of a tertiary alcohol in high yield and enantioselectivity.

Experimental Section

General procedure for allylic etherification: In a drybox, a toluene solution (0.5 mL) of K3PO4 (1.500 mmol, 318.4 mg) was added into a screw-capped vial. The activated catalyst (0.025 mmol, dissolved in toluene (1.0 mL) and alcohol (1.5 mmol)), and generated in situ by a method described previously, was added to these materials.[32]). A magnetic stir bar was added, and the vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum and removed from the drybox. The solution was stirred vigorously at room temperature (23°C) after addition of 1-phenyl-1-propyne (0.100 mmol, 12.5 μL) and allyl acetate (0.5 mmol) by syringe. When the reaction was complete (determined by GC analysis), the crude mixture was passed through a pad of silica gel, and eluted with 100 mL of ether. The resulting solutions were evaporated. The ratio of regioisomers was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (usually based on integration of the olefinic protons). The mixture was then purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to give the desired product.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We are grateful to the NIH (NIGMS GM-55382) for support of this work and Johnson-Matthey for iridium. S.U. acknowledges the J.S.P.S. fellowships for young scientists.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Trost BM, Van Vranken DL. Chem Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trost BM, Crawley ML. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2921. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haight AR, Stoner EJ, Peterson MJ, Grover VK. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8092. doi: 10.1021/jo0301907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu C, Hartwig JF. Angew Chem. 2004;116:4898. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:4794. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost BM, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4545. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans PA, Leahy DK. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez F, Ohmura T, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3426. doi: 10.1021/ja029790y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer C, Defieber C, Suzuki T, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1628. doi: 10.1021/ja0390707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mbaye MD, Renaud JL, Demerseman B, Bruneau C. Chem Commun. 2004:1870. doi: 10.1039/b406039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trost BM, Machacek MR, Tsui HC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7014. doi: 10.1021/ja050340q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uozumi Y, Kimura M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:161. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura M, Uozumi Y. J Org Chem. 2007;72:707. doi: 10.1021/jo0615403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyothier I, Defieber C, Carreira EM. Angew Chem. 2006;118:6350. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyabe H, Matsumura A, Moriyama K, Takemoto Y. Org Lett. 2004;6:4631. doi: 10.1021/ol047915t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyabe H, Yoshida K, Yamauchi M, Takemoto Y. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2148. doi: 10.1021/jo047897t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang L, Burke SD. Org Lett. 2002;4:3411. doi: 10.1021/ol026504e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kienen E, Sahai M, Roth Z, Nudelman A, Herzig J. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3558. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trost BM, McEachern EJ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12702. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trost BM, Zhang T. Org Lett. 2006;8:6007. doi: 10.1021/ol0624878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H, Men H, Lee C. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1336. doi: 10.1021/ja039746y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans PA, Leahy DK. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7882. doi: 10.1021/ja026337d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans PA, Leahy DK, Slieker LM. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:3613. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans PA, Leahy DK, Andrews WJ, Uraguchi D. Angew Chem. 2004;116:4892. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:4788. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohmura T, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15164. doi: 10.1021/ja028614m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiener CA, Shu C, Incarvito C, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14272. doi: 10.1021/ja038319h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shu C, Leitner A, Hartwig JF. Angew Chem. 2004;116:4901. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:4797. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leitner A, Shu C, Hartwig JF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307967101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leitner A, Shekhar S, Pouy MJ, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15506. doi: 10.1021/ja054331t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leitner A, Shu C, Hartwig JF. Org Lett. 2005;7:1093. doi: 10.1021/ol050029d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita Y, Gopalarathnam A, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7508. doi: 10.1021/ja0730718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graening T, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17192. doi: 10.1021/ja0566275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weix DJ, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7720. doi: 10.1021/ja071455s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.For representative publications from other investigators on the asymmetric allylic substitution with nitrogen and carbon nucleophiles using the cyclometalated iridium catalyst developed in our laboratory, see: Weihofen R, Tverskoy E, Helmchen G. Angew Chem. 2006;118:5673. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601472.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5546.Polet D, Alexakis A, Tissot-Croset K, Corminboeuf C, Ditrich K. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3596. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501180.Tissot-Croset K, Polet D, Alexakis A. Angew Chem. 2004;116:2480. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353744.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2426.Singh OV, Han H. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:774. doi: 10.1021/ja067966g.

- 34.Nelson SG, Bungard CJ, Wang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13000. doi: 10.1021/ja037655v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson SG, Wang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4232. doi: 10.1021/ja058172p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.a) Terao J, Todo H, Begum Shameem A, Kuniyasu H, Kambe N. Angew Chem. 2007;119:2132. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2086. [Google Scholar]; b) Takahashi G, Shirakawa E, Tsuchimoto T, Kawakami Y. Chem Commun. 2005:1459. doi: 10.1039/b417353h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.For selected primary references on decarboylative allyation of carbon and nitrogen nucleophiles see references [38–43], and for a recent review on this topic, see You S, Dai L. Angew Chem. 2006;118:5372–5374.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5246–5248. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5246–5248. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889.

- 38.Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15044. doi: 10.1021/ja044812x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tunge JA, Burger EC. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:1715. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trost BM, Xu J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2846. doi: 10.1021/ja043472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trost BM, Xu J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17180. doi: 10.1021/ja055968f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohr JT, Nishimata T, Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11348. doi: 10.1021/ja063335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh OV, Han H. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:774. doi: 10.1021/ja067966g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.