Abstract

Objectives

To: (1) quantify at which proximal caries lesion depths dentists in regular clinical practice intervene restoratively, based on hypothetical scenarios that present radiographic images and patient background information, and (2) identify characteristics that are associated with restorative intervention in lesions that have penetrated only the enamel surface.

Methods

Dentists in a practice-based research network (www.DentalPBRN.org) who reported doing at least some restorative dentistry were surveyed (n=901). Dentists were asked to indicate at which lesion depth they would intervene restoratively based on a series of radiographic images depicting interproximal caries at increasing lesion depths in a mandibular premolar tooth. Dentists were also questioned regarding two caries risk scenarios: one patient with low caries risk and another at higher risk. We used logistic regression to analyze associations between the decision to intervene restoratively and specific dentist, practice, and patient characteristics.

Results

Five hundred (56%) DPBRN practitioner-investigators completed the survey. In a high caries risk patient, 66% of dentists indicated that they would restore a proximal enamel lesion, and 24% would once the lesion had reached into the outer one-third of the dentin. In a low caries risk patient, 39% of dentists reported that they would restore an enamel lesion, and 54% would once the lesion had reached into the outer one-third of the dentin. In multivariate analyses, when accounting for dentist and practice characteristics, dentists in large group practices were less likely to intervene surgically for enamel caries regardless of patient's caries risk.

Conclusions

Restorative treatment thresholds based on radiographic lesion depth varied substantially among dentists. Most dentists would restore lesions that were still within the enamel surface for high caries risk individuals. Dentists’ decisions to intervene surgically in the caries process differ by patient caries risk. For a case scenario involving a high caries risk individual, practice busyness, type of practice model, and gender were significant when deciding for surgical intervention. However, for a case scenario involving a low caries risk individual only type of practice model was significant when deciding for surgical intervention.

Keywords: caries diagnosis, treatment threshold, practice model, private practice, public health, risk assessment, practice characteristics

INTRODUCTION

The interproximal tooth surface is considered an important and challenging site regarding diagnosis and treatment of dental caries (1, 2). Criteria for when to intervene restoratively for interproximal caries have been discussed extensively (3-8) and substantial variation exists among clinicians for this treatment (9-12).

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Restorative treatment decisions based on radiographic images differ by dentist and practice characteristics.

Visual examination of interproximal surfaces is difficult and radiography can assist in caries diagnosis of these surfaces (13-17). Radiographs reveal 88% more lesions on interproximal surfaces when compared with visual examinations alone (13), and have acceptable levels of correlation with microbiological evaluation (14, 18). However, a certain degree of subjectivity exists when radiographs are interpreted, particularly when lesions approach the dentin surface (18). Consequently, dentists may over or underestimate the depth of penetration of interproximal lesions (19, 20). Therefore, interproximal type of lesions involving the dentin surface represents a controversial issue both in clinical diagnosis and treatment approaches (18, 21, 22).

Appropriate treatment thresholds become a critical issue for clinicians who might prematurely opt for restorative treatment relying only on depth of penetration of dental caries and not considering the presence of cavitation. Studies have attested changes in the disease pattern of dental caries (23, 24). In the absence of cavitation, caries that have penetrated in the enamel or dentin surfaces can now be left without surgical treatment and be arrested through the remineralization process (25-27).

While not all interproximal caries restorative treatment thresholds have been validated, the restorative intervention of non-cavitated caries confined to enamel is inappropriate. Consensus has been reached regarding the potential for non-cavitated enamel lesions to reverse (28). Extensive research shows that enamel lesions that are not cavitated can be arrested through proper fluoride treatment and patient education (29-37).

The extent to which clinicians employ enamel-based thresholds when deciding whether or not to intervene restoratively must be understood before effective interventions foster appropriate treatment by clinicians in regular clinical practice can be designed. This study addressed features of that process by quantifying the distribution of radiographic thresholds for restorative intervention among a diverse group of dentists in regular clinical practice. We also assessed contributions of dentists’ personal and practice characteristics that are associated with enamel-based thresholds. The study was conducted by The Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN), which is a consortium of dental practices with a broad representation of practice types, treatment philosophies, and patient populations. DPBRN has substantial diversity in race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, geography and rural/urban area of residence among both its practitioners and the patients whom they serve (38, 39). Our objectives were to: (1) quantify at which proximal caries lesion depths dentists in regular clinical practice intervene restoratively, based on hypothetical scenarios that present radiographic images and patient's background information, and (2) identify characteristics that are associated with restorative intervention in proximal lesions that have penetrated only the enamel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cross-sectional study design employed a single administration of a questionnaire to all DPBRN dentist practitioner-investigators who indicated on their DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire that they perform at least some restorative dentistry in their practices (n=901). The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Board (IRB) of all participating regions. As part of enrollment in DPBRN, all practitioner-investigators complete an Enrollment Questionnaire about their practice characteristics and themselves. This questionnaire and other details about DPBRN are publicly available at http://www.DentalPBRN.org and www.dentalpbrn.org/users/related_links/default.asp.

This report provides results based on questions from the DPBRN “Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Treatment” questionnaire. The full questionnaire, which comprised DPBRN's first study to involve all five DPBRN regions (“Study 1”), is publicly available at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/users/publications/Supplement.aspx. Methodologic particulars, such as sample selection, the recruitment process, length of the field phase, the data collection process, procedures used during a pilot study and pre-testing of the questionnaire, have been reported previously (40).

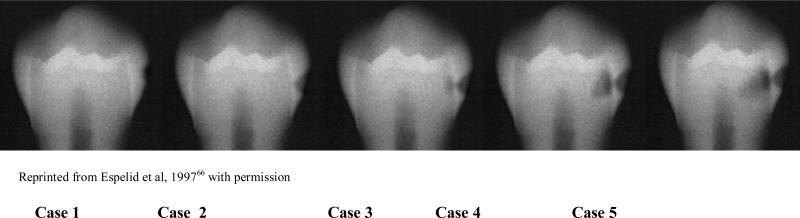

Participants indicated their recommended treatment from among options for cases presented in the questionnaire. A series of five radiographic images of caries located on the interproximal surface of a mandibular premolar, together with a description of the patient, were presented that portrayed increasingly deep carious lesions. The treatment decision (shallowest depth at which the dentist would restore the tooth) for the case was requested under two different caries risk conditions: first, where the patient had minimal risk, and second, where the patient was at higher risk for caries. The exact wording of each case scenario is provided in Figure 1 Case 1 presented a radiolucency in the outer half of enamel. Case 2 had a radiolucency reaching the inner half of enamel. Cases 3, 4, and 5 presented radiolucencies in the outer, middle and inner thirds of dentin respectively (41).

Figure 1. Scenarios asked of participating dentists.

Case scenario: The patient is a 30 year old female with no relevant medical history. She has no complaints and is in your office today for a routine visit. She has been attending your practice on a regular basis for the past 6 years.

Questions 1 and 2: Please indicate the one number that corresponds to the lesion depth at which you would do a permanent restoration (composite, amalgam, etc.) instead of only doing preventive therapy

1. If the patient has no dental restorations, no dental caries, and is not missing any teeth.

2. If the patient has 12 teeth with existing dental restorations, heavy plaque and calculus, multiple Class V white spot lesions, and is not missing any teeth.

Dentists were also asked about assessment of caries risk (“Do you assess caries risk for individual patients in any way?”). Information regarding dentists’ demographics and practice characteristics (Table 2) was already gathered from the enrollment questionnaire (www.dentalpbrn.org/users/related_links/default.asp).

Table 2.

Percentage of practitioner-investigators who would recommend restorative intervention for interproximal radiographic images on case 1 through case 5, based on separate scenarios for low and higher caries risk individual

| Low caries risk scenario Frequency (%) n=500 | Higher caries risk scenario Frequency (%) n=499 | |

|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 8 (1.8) | 44 (9) |

| C-2 | 194 (39) | 332 (66.4) |

| C-3 | 273 (54) | 120 (24) |

| C-4 | 24 (5) | 2 (0.4) |

| C-5 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

Study Population

This study queried dentists participating in DPBRN, which comprises outpatient dental practices that have affiliated to investigate research questions and to share experiences and expertise. DPBRN comprises five regions: AL/MS: Alabama/Mississippi, FL/GA: Florida/Georgia, MN: dentists employed by HealthPartners and private practitioners in Minnesota, PDA: Permanente Dental Associates in cooperation with Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, and SK: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (42). DPBRN dentist practitioner-investigators were recruited through continuing education courses and mass mailings to licensed dentists within the participating regions.

DPBRN dentists can also be characterized by “type of practice”, for which we categorized each dentist as being in either: (1) a solo or small group private practice (SGP); (2) a large group practice (LGP); or (3) a public health practice (PHP). “Small” practices were defined as those that had 3 or fewer dentists. Public health practices were defined as those that receive the majority of their funding from public sources.

Analyses of the characteristics of DPBRN dentists and their practice characteristics suggest that DPBRN dentists have much in common with dentists at large (38), while at the same time offering substantial diversity within the network with regard to these characteristics (39).

Variable Selection

To identify dentists’ and practice characteristics that are associated with dentists’ use of an enamel-based interproximal restorative treatment threshold, explanatory variables were identified based on extant literature related to theoretical models of factors associated with dentists’ treatment decisions (8) and dental practice characteristics (42, 43). The explanatory variables that were used for bivariate analyses are listed in Table 2. These variables included measures of: (1) dentist's individual characteristics (year since graduation from dental school, race/ethnicity, and gender); (2) practice setting (practice busyness, waiting time for a restorative dentistry appointment, DPBRN region and type of practice); (3) patient population (dental insurance coverage, percent of patients who self-pay, age distribution, and racial/ethnic distribution); and (4) dental procedure characteristics (percent of patient contact spent each day doing restorative procedures, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic procedures, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning).

Additionally a logistic regression model tested the potential contribution of variables showing significant or near-significant bivariate associations.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.1 (Cary, N.C.). A p-value of .05 was considered statistically significant. Bivariate analyses examined associations between the explanatory variables and decisions for restorative intervention for low and high caries risk individuals. Chi-square tests were used for bivariate analysis when explanatory variables were categorical; t-tests were used when explanatory variables were continuous. To simultaneously examine the effect of an explanatory variable on outcome after adjusting for the effect of other explanatory variables, two logistic regressions were performed using stepwise selection. Due to the multicollinearity of region and type of practice, only the “type of practice” variable was tested in the logistic regression model. The race/ethnicity of dentist was not used in analysis because of small cell sizes. McNemar's test (appropriate for testing marginal equality of paired categorical data) was used to determine if dentists reported the decision to restore differently for the two caries risk scenarios.

RESULTS

Questionnaires were mailed to all (n=901) eligible dentists and 500 (56%) were completed and returned. Among the eligible participants who decided to participate, there were no differences by gender, area of specialty, or years since dental school graduation when compared to practitioners who chose not to participate. Not all dentists responded to all questions; therefore, sample sizes differ in some instances.

Table 2 summarizes the percentage of dentists who would recommend restorative intervention for Cases 1 through 5. A total of 39% of practitioner-investigators reported that they would intervene with a restoration when the lesion was in the inner one-half of enamel for a patient at low caries risk (Case 2); 2% of dentists would even intervene restoratively when the lesion was still in the outer one-half of enamel (Case 1), but most dentists (54%) would not intervene unless the lesion was into the outer one-third of the dentin (Case 3). Conversely, in patients with a higher caries risk, the majority of dentists (75%) reported that they would intervene with a restoration when the lesion was still in the outer or inner one-half of the enamel (Case 2). Sixty nine percent of dentists reported that they assess patients’ caries risk during part of routine treatment planning. Of these, only 18% (n=63) use a special form for caries risk assessment. Dentists from PDA (100%), SK (94%), and MN (93%) regions reported assessing caries risk as part of routine treatment planning significantly more often than dentists from the AL/MS (65%) and FL/GA (63%) regions.

We analyzed for associations between the decision to intervene into enamel lesions (combining Cases 1 and 2) or dentin lesions (combining Cases 3, 4, and 5) and the study explanatory variables. Results are shown on Tables 3 (using low caries risk individual scenario) and 4 (using a higher caries risk individual scenario). These tables depict the distributions for explanatory variables among those who would recommend restorative intervention when the caries lesion was still in the enamel. No significant differences were found for the variables year since graduation from dental school, waiting time for a restorative dentistry appointment, dental insurance coverage, and percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions for both scenarios, low and higher caries risk individuals. Table 3, results for a scenario using a low caries risk individual, shows that male dentists would intervene significantly more often in enamel surfaces than female dentists (p=.002). Dentists in practices that are “not busy enough” also would intervene significantly more often in enamel surfaces (p=.018). Significant differences were found by DPBRN region (p<.001). Practitioner-investigators from the MN, PDA, and SK regions were less likely to recommend intervening restoratively with enamel lesions, as compared to practitioner-investigators from the AL/MS and FL/GA regions. Additionally, significant differences were evident by type of practice (p<.001). Practitioner-investigators who work in large group practices (LGP) and public health practices (PHP) were less likely to recommend intervening restoratively on enamel lesions, as compared to practitioner-investigators who work in solo or small group private practices (SGP). Regarding dental procedure characteristics, practitioners who spent between 50 to 80% of time each day doing restorative procedures (p=.007), who spent 31% or more of time each day doing esthetic procedures (p=.005), and who did not assess caries risk as a routine part of treatment planning (p=.018), were more likely to intervene on enamel surfaces, compared to their counterparts. In the logistic regression analysis (Table 5), only the type of practice (p-value < .0001) was significant after adjusting for other explanatory variables. The odds of recommending restoration in enamel were significantly lower for dentists practicing in LGP versus dentists practicing in SGP (OR=.11, 95% CI =[.05, .23]).

Table 3.

Percent of DPBRN practitioner-investigators who would recommend restorative intervention for interproximal caries based on radiograph lesion depth only into the enamel - for a low caries risk patient - by dentist's and practice's characteristics.

| (n=500) | Percent of dentists who would recommend restorative intervention at enamel depth, n=202 (40%) | p-value * statistical significance |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of dentist | |||

| Male (412) | 43% | 0.002* | |

| Female (88) | 26% | ||

| Practice busyness | |||

| Too busy to treat all people requesting appts (53) | 23% | 0.018* | |

| Provided care to all, but the practice was overburdened (86) | 36% | ||

| Provided care to all, but the practice was not overburdened (267) | 42% | ||

| Not busy enough (78) | 49% | ||

| Region | |||

| AL/MS (290) | 49% | <.001* | |

| FL/GA (101) | 49% | ||

| MN (30) | 20% | ||

| PDA (50) | 8% | ||

| SK (29) | 0% | ||

| Type of practice | |||

| SGP (417) | 48% | <.001* | |

| LGP (77) | 9% | ||

| PHP (21) | 0% | ||

| Percent of patients who self-pay | |||

| 0 (14) | |||

| 1-30% (235) | 14% | 0.2454 | |

| 31-50% (126) | 41% | ||

| >51% (102) | 42% | ||

| 41% | |||

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures | |||

| 50% or less (190) | 32% | 0.007* | |

| >50 to 80% (260) | 47% | ||

| > than 80% (44) | 39% | ||

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic procedures | |||

| 0 (7) | 0% | ||

| 1-30% (401) | 37% | 0.005* | |

| 31-50% (50) | 56% | ||

| > than 50% (23) | 52% | ||

| Whether or not caries risk is done as routine part of treatment planning | Yes (n=344) | 38% | 0.018* |

| No (n=134) | 49% | ||

Table 5.

Results for the logistic regression related to % of DPBRN practitioner-investigators who would recommend restorative intervention for interproximal caries based on radiograph lesion depth only into the enamel - for low and high caries risk patient - by dentist's and practice's characteristics.

| Explanatory variables | Low Caries Risk∞ | High Caries Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of dentist | * | p=.0202 |

| Practice busyness | * | p=.0215 |

| Region | * | * |

| Type of practice | p < .0001 | p < .0001 |

| Percent of patients who self-pay | * | * |

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures | * | * |

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic procedures | * | * |

| Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning | * | * |

22 observations were deleted from the logistic regression analysis due to lack of convergence in estimation of model parameters

p >.05

The same pattern held for the bivariate analysis of the decision to intervene into enamel (combining Cases 1 and 2) or dentin (combining Cases 3, 4, and 5) and the study explanatory variables in a higher caries risk scenario (Table 4). The only two exceptions were that no significant difference was found according to the percent of time spent each day doing restorative procedures (p=.312), and dentists working in offices with a higher percent of patients who self-pay would intervene more often on enamel lesions (p=.003). In the logistic regression analysis (Table 5), type of practice (p < .0001), gender (p=.0202), and busyness (p=.0215) were significant after adjusting for other explanatory variables. The odds of recommending restoration in enamel were higher for dentists practicing in SGP versus PHP (OR=5.49, 95% CI =[1.65,18.31]), higher for male dentists as compared to female dentists (OR=1.99, 95% CI =[1.11,3.56]), and lower for the highest level of busyness (“Too busy to treat all people requesting appointments”) compared to the “Provided care to all but not overburdened” level of busyness [(OR=.33, 95% CI =[.17,.67]).

Table 4.

Percent of DPBRN practitioner-investigators who would recommend restorative intervention for interproximal caries based on radiograph lesion depth only into the enamel - for a high caries risk patient - by dentist's and practice's characteristics.

| (n=499) | Percent of dentists who would recommend restorative intervention at enamel depth, n=376 (75%) | p-value * statistical significance |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of dentist | |||

| Male (413) | 79% | <.001* | |

| Female (86) | 59% | ||

| Practice busyness | |||

| Too busy to treat all people requesting appts (53) | 57% | 0.007* | |

| Provided care to all, but the practice was overburdened (84) | 74% | ||

| Provided care to all, but the practice was not overburdened (267) | 79% | ||

| Not busy enough (79) | 78% | ||

| Region | |||

| AL/MS (291) | 84% | <.001* | |

| FL/GA (100) | 86% | ||

| MN (30) | 47% | ||

| PDA (50) | 52% | ||

| SK (28) | 21 | ||

| Type of practice | |||

| LGP (76) | 82% | <.001* | |

| SGP (407) | 47% | ||

| PHP (16) | 31% | ||

| Percent of patients who self-pay | |||

| 0 (14) | |||

| 1-30% (235) | 36% | 0.003* | |

| 31-50% (126) | 77% | ||

| >51% (102) | 79% | ||

| 73% | |||

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures | |||

| 50% or less (190) | 74% | 0.312 | |

| >50 to 80% (260) | 78% | ||

| > than 80% (43) | 70% | ||

| Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic procedures | |||

| 0 (7) | 29% | 0.007* | |

| 1-30% (400) | 74% | ||

| 31-50% (50) | 86% | ||

| > than 50% (23) | 83% | ||

| Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning | Yes (n=342) | 71% | <.001* |

| No (n=135) | 87% | ||

DISCUSSION

There has been pronounced change in the epidemiology and disease pattern of dental caries (23, 24, 44). With the advent of fluoride, a paradigm shift has occurred, and enamel and dentin lesions that are not cavitated can be arrested through the remineralization (25-27, 46). National organizations in the United States and abroad have recently provided clinical guidelines (46-48). Some guidelines recommend that prevention should be attempted before any surgical treatment is done (48). Current expert opinion suggests that restorative intervention for non-cavitated lesions is inappropriate (46). Despite the latest scientific evidence, most DPBRN dentists still chose to intervene on enamel lesions in high caries risk individuals, and on outer dentin lesions irrespective of patient's caries risk status.

Similarly to the current study the variations in diagnosis and treatment of dental caries among clinicians were highest when assessing the outer dentin third (49, 50). The occurrence of cavitation among these types of lesions can range between 20% and 90% (51-53).

Although it is possible that respondents could misinterpret the severity of the lesions depicted in the radiographic images, it is unlikely that such misinterpretation could occur differentially by the explanatory variables examined in this study. Thus, the differences in willingness to intervene restoratively are likely reflections of true differences in dentists’ beliefs about what represents the appropriate point in lesion progression to initiate such treatment.

Studies have reported that restorative thresholds which have been reported to be used by dentists may actually be poorly correlated with the number of positive treatment decisions actually made (54). Dentists’ perceptions of dental caries depth using bitewing radiographs play a major but variable role in their restorative decisions for interproximal tooth surfaces (6, 7, 55). Therefore, the results of the current study should be interpreted with caution as it relies on the information provided by dentists at the time that they answered of the survey and not at the actual treatment time.

The differences in response by dentists regarding restorative treatment threshold might also be related to interplay of several other reasons which are summarized below. The most prominent difference regarding restorative treatment threshold was related to the type of practice and the DPBRN region. Dentists participating in solo or small group private practice were more likely to intervene surgically when lesions were present in enamel, but had not yet penetrated into the dentin than dentists who participate in large group practices or public health practices. In solo or small group private practices, operational and management considerations may be at their strongest compared to LGP and PHP, and therefore more strongly influence treatment choices. If practice revenues and costs are functions of the number and type of procedures being done, practices that solely depend on these variables may be more likely to endorse procedures that incur higher fees. Therefore, dentists participating in this type of practice may feel incentivized to restore enamel lesions that could otherwise be treated with preventive management. Most of the dentists in the AL/MS and FL/GA regions are solo or belong to small group private practices. Dentists participating in MN and PDA regions, however, primarily belong to large group practices, such as the Health Partners Dental Group and the Permanente Dental Associates, both of which have a fixed base salary and annual individual incentive programs. Although dentists in large group practices may have production or revenue incentives, these are not their main source of income. Therefore, dentists are not solely reimbursed based on the number of procedures and may feel less incentivized to intervene at the earliest stage of the disease process when it has the potential to be reversible. Additionally, dentists participating in large group practices might in an environment in which assessment of caries risk and standardization of diagnosis and treatment of interproximal caries is more consistent across all dentists in the group. The current study corroborates this thought by showing that dentists from the MN and PDA regions assessed caries risk significantly more than dentists from the AL/MS and FL/GA regions.

The current study showed that dentists belonging to busier practices and practices with higher percentages of time spent each day doing restorative and esthetic procedures, recommended restorative treatment more often on enamel surfaces. As mentioned earlier, if revenue is posed solely as a function of the number and type of procedures being done, busier practices and practices with significant emphasis on restorative procedures will most likely treat all types of lesions, including those that could otherwise be managed with less-costly treatment.

Dentists in Scandinavia chose not to restore lesions that were limited to enamel; restorative treatment was predominantly recommended for surfaces that involved dentin. Other studies in Scandinavia are consistent with these findings (56, 57). Current treatment strategy in Scandinavia is based on diagnosis of caries activity and assessment of the actual caries risk (58). In contrast, in the United States this concept has only been introduced in the past 15 years (59, 60). Additionally, Scandinavian dental practices have restrictive criteria when placing the first restoration in a tooth (61) and, as a result, there also are more Scandinavian studies that have demonstrated successful monitoring of interproximal enamel lesions (10, 22). About half of the participating DPBRN practices from the Scandinavia region are subsidized by the public health system. The government is involved in the health management in some Scandinavian regions (48) and prevention is promoted extensively to the public at large (62). With easier access to care, the recall frequency by Scandinavian patients is more predictable, so Scandinavian dentists may be less challenged when monitoring initial lesions.

The current study shows that practitioner-investigators who do not routinely assess patient's caries risk were more likely to intervene on enamel lesions. These dentists may approach a carious lesion as a separate entity and not as a consequence of a disease process. Extensive literature suggests that the “cure” for the caries disease does not rely on the placement of a restoration, but on patient education and individual assessment of caries risk followed by a change in the environment of this multi-factorial disease (63, 64). Patients’ treatment plans should be individual and based on patients’ caries risk. Patients must be educated regarding dietary and oral health habits. The process of remineralization is a dynamic process, can only occur if there is adequate time between the cycles of acid challenge, and therefore it takes time to remineralize an active caries lesion. If patients are not compliant with dentists’ recommendations for their individual treatments, dentists might feel challenged and less inclined to monitor over time these active caries lesions. Despite the validation through publication and national consensus of non-surgical treatment for non-cavitated lesions, this information was not fully implemented into some practices. In general, the translation of research into clinical practice has been a slow process. It is estimated that only 14 percent of new science enters daily clinical practice, and that process takes an estimated average of 17 years (65).

CONCLUSION

Restorative treatment thresholds based on radiographic images varied substantially among dentists. Most dentists would choose to restore lesions that were within the enamel surface in a patient who is at high risk for caries.

Dentists’ decisions to intervene surgically in the caries process differ by patient caries risk. For a case scenario involving a high caries risk individual, practice busyness, type of practice model, and gender were significant when deciding for surgical intervention. However, for a case scenario involving a low caries risk individual only type of practice model was significant when deciding for surgical intervention.

Table 1.

Dental practice characteristics tested for their association with the treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators

| Dentist's Individual Characteristics | Practice Setting | Patient Population | Dental Procedure Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year since graduation from dental school | Practice busynessa | Dental insurance coverage | Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative proceduresc |

| Race/ ethnicity | Waiting time for restorative dentistry | Percent of patients who self-pay | Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic proceduresc |

| Gender | DPBRN region of practice | Age distribution | Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractionsd |

| Type of practiceb | Racial/ethnic distribution | Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning |

1=too busy to treat all people requesting appointments, 2=provided care to all who requested appointments, but the practice was overburdened; 3= provided care to all who requested appointments, and the practice was not overburdened; 4= not busy enough-the practice could have treated more patients

1=solo or small group private practice; 2=large group practice; 3=public health practice

0=none; 1=1-30% of the time; 2=31 to 50% of the time; 3=more than 50% of the time.

0=none; 1=1-20% of the time; 2=21 to 30% of the time; 3=more than 30% of the time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ivar Mjör, who served as a consultant during the planning phase of the research project, and all DPBRN practitioner-investigators who responded to the questionnaire. Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge grants U01-DE-16746 and U01-DE-16747 from NIDCR-NIH. The DPBRN Collaborative Group comprises practitioner-investigators, faculty investigators, and staff who contributed to this DPBRN activity. A list of these names is provided at http://www.dpbrn.org/users/publications/Default.aspx.

Footnotes

The DPBRN Collaborative Group comprises practitioner-investigators, faculty investigators, and staff members who contributed to this DPBRN activity. A list of these persons is at http://www.dpbrn.org/users/publications/Default.aspx

Contributor Information

Valeria V Gordan, College of Dentistry, Department of Operative Dentistry at University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA..

Cynthia W Garvan, College of Education, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA..

Marc W. Heft, College of Dentistry, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Oral Diagnostic Sciences, at University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA..

Jeffrey L Fellows, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Oregon, USA..

Vibeke Qvist, Department of Cariology and Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark..

D. Brad Rindal, HealthPartners, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA..

Gregg H Gilbert, Department of Diagnostic Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA..

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson M, Stecksen-Blicks C, Stenlund H, Ranggard L, Tsilingaridis G, Mejare I. Detection of approximal caries in 5-year old Swedish children. Caries Res. 2005;39:92–99. doi: 10.1159/000083153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mejare I, Stenlund H, Zelezny-Holmlund C. Caries incidence and lesion progression from adolescence to young adulthood: a prospective 15-year cohort study in Sweden. Caries Res. 2004;38:130–141. doi: 10.1159/000075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espelid I. Radiographic diagnoses and treatment decisions on approximal caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mileman PA, Espelid I. Decisions on restorative treatment and recall intervals based on bitewing radiographs. A comparison between national surveys of Dutch and Norwegian practitioners. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuttal NM, Pitss NB. Restorative treatment thresholds reported to be used by dentists in Scotland. Brit Dent J. 1990;169:119–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis DW, Kay EJ, Main PA, Pharoah MG, Csima A. Dentists’ variability in restorative decisions, microscopic and radiographic caries depth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis D, Kay E, Main P, Pharoah M, Csima A. Dentists’ stated restorative treatment thresholds and their restorative and caries depth decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56(4):176–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bader JD, Shugars DA. What do we know about how dentists make caries-related treatment decisions? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thylstrup A, Bille J, Qvist V. Radiographic and observed tissue changes in approximal carious lesions at the time of operative treatment. Caries Res. 1986;20:75–84. doi: 10.1159/000260923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tveit AB, Espelid I, Skodje F. Restorative treatment decisions on approximal caries in Norway. Int Dent J. 1999;49:165–172. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.1999.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yorty JS, Brown KB. Caries risk assessment/treatment programs in US dental schools. J Dent Educ. 1999;63:745–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark TD, Mjör IA. Current teaching of cariology in North American dental schools. Oper Dent. 2001;26:412–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimmer PA, Pitts NB. Temporary elective tooth separation as a diagnostic aid in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 1990;169:87–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidd EA, Pitts NB. A reappraisal of the value of the bitewing radiograph in the diagnosis of approximal caries. Br Dent J. 1990;169:195–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dove SB. Radiographic diagnosis of dental caries. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopcraft MS, Morgan MV. Comparison of radiographic and clinical diagnosis of approximal and occlusal dental caries in a young adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young DA, Featherstone JDB. Digital imaging, fiber-optic transillumination, F-speed radiographic film and depth of approximal lesions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1682–1687. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratledge DK, Kidd EA, Beighton D. A clinical and microbiological study of approximal carious lesions. Part 1: the relationship between cavitation, radiographic lesion depth, the site-specific gingival index and the level of infection of the dentine. Caries Res. 2001;35:3–7. doi: 10.1159/000047423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen JH, Hansen B, Wenzel A, Hintze H. Relationship between histological and radiographic caries lesion depth measured in images from four digital radiography systems. Caries Res. 2004;38:34–38. doi: 10.1159/000073918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seneadza V, Koob A, Kaltschmitt J, Staehle HJ, Duwenhoegger J, Echholz P. Digital enhancement of radiographs for assessment of interproximal dental caries. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2008;37:142–148. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/51572889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunder N, von der Fehr FR. Approximal cavitation related to bitewing image and caries activity in adolescents. Caries Res. 1996;30:143–147. doi: 10.1159/000262151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mejare I, Sundberg H, Espelid I, Tveit B. Caries assessment and restorative treatment thresholds reported by Swedish dentists. Acta Odontol Scand. 1999;57:149–154. doi: 10.1080/000163599428887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugoson A, Koch G, Slotte C, Bergendal T, Thorstensson B, Thorstensson H. Caries prevalence and distribution in 20-80-year-olds in Jönköping, Sweden, in 1973, 1983, and 1993. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:90–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028002090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugoson A, Koch G, Hallonsten AL, Norderyd J, Aberg A. Caries prevalence and distribution in 3-20-year-olds in Jönköping, Sweden, in 1973, 1983, and 1993. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:83–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028002083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Twesme DA, Firestone AR, Heaven TJ, Feagin FF, Jacobson A. Air-rotor stripping and enamel demineralization in vitro. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;105:142–152. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawyer KK, Donly KJ. Remineralization effects of a sodium fluoride bioerodible gel. Am J Dent. 2004;17:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donly KJ, Brown DJ. Indetify, protect, restore: emerging issues in approaching children's oral health. Gen Dent. 2005;53:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Professionally applied topical fluoride:evidence-based clinical recommendations. JADA. 2006;137(8):1151–1159. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marinelli CB, Donly KJ, Wefel JS, Jakobsen JR, Denehy GE. An in vitro comparison of three fluoride regimens on enamel remineralization. Caries Res. 1997;31:418–422. doi: 10.1159/000262432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozier RG. Effectiveness of methods used by dental professionals for the primary prevention of dental caries. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1063–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Featherstone JD, Adair SM, Anderson MH, Berkowitz RJ, Bird WF, Crall JJ, Den Bestern PK, Donly KJ, Glassman P, Milgrom P, Roth JR, Snow R, Stewart RE. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:257–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moberg Skold U, Petersson LG, Lith A, Birkhed D. Effect of school-based fluoride varnish programmes on approximal caries in adolescents from different caries risk areas. Caries Res. 2005;39:273–279. doi: 10.1159/000084833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Jue B, Shain S, Hoover CI, Featherstone JD, Gansky SA. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2006;85:172–176. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altenburger MJ, Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, Hellwig E. Remineralization of artificial interproximal carious lesion using a fluoride mouthrinse. Am J Dent. 2007;20:385–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Godoy F, Hicks MJ. Maintaining the integrity of the enamel surface: the role of dental biofilm, saliva and preventive agents in enamel demineralization and remineralization. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(Suppl):25S–34S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ten Cate JM. Remineralization of deep enamel dentine caries lesions. Aust Dent j. 2008;53:281–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ten Cate JM, Buijs MJ, Miller CC, Exterkate RA. Elevated fluoride products enhance remineralization of advanced enamel lesions. J Dent Res. 2008;87:943–947. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V, for the DPBRN Collaborative Group Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Gen Dent. 2008 accepted for publication. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V, for the DPBRN Collaborative Group Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. Manuscript under review at the Journal of the American Dental Association. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, Richman JS, Qvist V, Fellows JL, Rindal DB, Gilbert GH, for the Dental PBRN Collaborative Group Restorative Treatment Thresholds for Primary Caries by Dental Practice-Based Research Network Dentists. JADA. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0136. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Espelid I, Tveit AB, Fjelltveit A. Variations among dentists in radiographic detection of occlusal caries. Caries Res. 1994;28:169–175. doi: 10.1159/000261640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MC, DPBRN Collaborative Group The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Jan;139(1):74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert GH, Shewchuk RM, Litaker MS. Effect of dental practice characteristics on racial disparities in patient-specific tooth loss. Med Care. 2006;44:414–420. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207491.28719.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathaler TM. Caries status in Europe and predictions of future trends. Caries Res. 1990;24:381–396. doi: 10.1159/000261302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thylstrup A, Qvist V. Principal enamel and dentine reactions during caries progression. In: Thylstrup A, Leach SA, Qvist V, editors. Dentine and Dentine Reactions in the Oral Cavity. IRL Press; Oxford: 1987. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 46.NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement. 2001.

- 47.American Dental Association Council. 2006.

- 48.the Norwegian Public Oral health Act of 1983 http://www.lovdata.no/all/nl-19830603-054.htm.

- 49.Espelid I, Tveit AB. Diagnostic quality and observer variation in radiographic diagnoses of approximal caries. Acta Odontol Scand. 1986;44:39–46. doi: 10.3109/00016358609041296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traebert J, Wesolowski CI, de Lacerda JT, Marcenes W. Thresholds of restorative decision in dental caries treatment among dentists from small Brazilian cities. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bille J, Thylstrup A. Radiographic diagnosis and clinical tissue changes in relation to treatment of approximal carious lesions. Caries Res. 1982;16:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000260568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mejare I, Malmgren B. Clinical and radiographic appearance of proximal carious lesions at the time of operative treatment in young permanent teeth. Scan J Dent Res. 1986;94:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1986.tb01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akpata ES, Farid MR, al-Saif K, Roberts EA. Cavitation at radiolucent areas on proximal surfaces of posterios teeth. Caries Res. 1996;30:313–316. doi: 10.1159/000262336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kay E, Nuttall N, Knill-Jones R. Restorative treatment thresholds and agreement in treatment decision-making. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992 Oct;20(5):265–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mileman PA, Mulder H, Weele LT van der. Factors influencing the likelihood of successful decisions to treat dentin caries from bitewing radiographs. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:175–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lith A, Pettersson LG, Grondahl HG. Radiographic study of approximal restorative treatment in children and adolescents in two Swedish communities differing in caries prevalence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23:211–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lith A, Lindstrand C, Grondahl HG. Caries development in a young population managed by a restrictive attitude to radiography and operative intervention: II. A study at the surface level. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:232–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lagerlöf F, Oliveby A. Clinical implications: new strategies for caries treatment. In: Stookey GK, editor. Early detection of dental caries. School of Dentistry, Indiana University; Indianapolis, IN: 1996. pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ismail AI. Clinical diagnosis of precavitated carious lesions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lundeen TF, Roberson TM. Cariology: the lesion, etiology, prevention, and control. In: Sturdevant CM, Roberson TM, Heymann HO, Sturdevant JR, editors. The Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. Mosby; St Louis, Missouri: 1995. pp. 60–128. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mjor IA, Holst D, Eriksen HM. Caries and restoration prevention. JADA. 2008;139:565–570. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wendt LK. On oral health in infants and toddlers (thesis). Swed Dent J. 1995;106(suppl):62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. Systematic reviews of selected caries prevention and management methods. Community dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:399–411. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young DA, Featherstone JD, Roth JR. Curing the silent epidemic: caries management in the 21st century and beyond. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007 Oct;35(10):681–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boren SA, Balas EA. Evidence-based quality measurement. J Ambul Care Manage. 1999;22:17–23. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Espelid I, Tveit AB, Mejáre I, Nyvad B. Caries - New knowledge or old truths?. The Norwegian Dental Journal. 1997;107:66–74. [Google Scholar]