Abstract

4, 4′-methylenedianiline (DAPM) is the main building block for production of 4,4′-methylenediphenyldiisocyanate that has been widely used in the manufacturing of polyurethane materials including medical devices. Although it was revealed that damage to biliary epithelial cells of the liver and common bile duct occurred upon acute exposure to DAPM, the exact mechanism of DAPM toxicity is not fully understood. Both phase I and II biotransformations of DAPM, some of which generate reactive intermediates, are characterized in detail by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. The two most prominent metabolites found in rat bile (M2 and M7) implicated glutathione, glucuronic acid and glycine conjugations (phase II) following hydroxylation, and N-oxidation (phase I). Their decomposition pathways, as evidenced by MSn experiments, have been elucidated in detail.

Keywords: methylenedianiline, biliary metabolites, glutathione conjugation, glycine conjugation, glucuronidation

Introduction

One class of xenobiotics that has attracted much attention for its potential toxicity is the aromatic amines. Reports on toxic exposure to aromatic amines date back to the early 1900s.[1] The most common threat from those compounds results from accidental occupational and incidental environmental exposure.[2] It has been postulated[3] that reactive intermediates of the starting materials are primarily responsible for the toxicity, and that these activated forms bind with proteins critical to certain cellular functions. DAPM (also known as 4,4′-methylenedianiline or diaminodiphenylmethene), is an aromatic diamine (Fig. 1a) of considerable industrial and commercial importance. It has been used as a chemical intermediate in several syntheses, including certain isocyanates and polyurethane polymers. It has also been employed as the cross-linking agent for epoxy resins, and as an antioxidant and curative agent in the preparation of azo dyes and rubber products.[4,5]

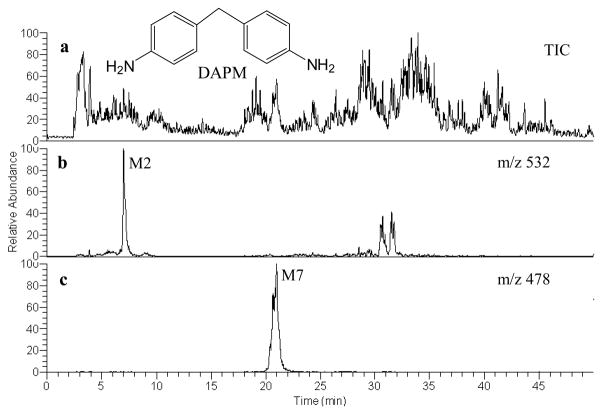

Fig. 1.

(a) LC/MS total ion chromatogram (TIC) of biliary metabolites in a rat dosed with methylenedianiline (DAPM); LC/MS reconstructed ion chromatogram of: (b) M2 at m/z 532; and (c) M7 at m/z 478

DAPM is an environmental contaminant which has potentially harmful effects on human and animal health. Early documentation of DAPM hepatoxicity was established in a study of residents of Epping (England) who had consumed DAPM-contaminated bread.[6] Although it was revealed that biliary epithelial cells of the liver and common bile duct could be injured upon acute exposure to DAPM,[7,8] the exact mechanism of DAPM toxicity is not fully elucidated. Other studies have shown that DAPM is an animal carcinogen, and histopathological abnormalities have been observed in the liver, kidney and lung of mice,[9] although metabolic pathways for bioactivation of DAPM have not yet been fully described.

With the introduction of various analytical techniques such as GC, HPLC and LC/MS, investigations of the biotransformations of DAPM have grown. Acetylated metabolites were reported to be found in urine, blood and vascular smooth muscle cells.[10, 11] However, their presence cannot explain the toxicity of DAPM. Other reactive and toxic metabolites are expected in bile, the likely route of exposure of bile duct cells to the proximate toxicant. Hemoglobin adduction with DAPM after conversion of the latter to an imine form was reported by Kautiainen and colleagues.[12] This biotransformation of DAPM into a reactive imine was speculated to be catalyzed by extrahepatic peroxidase enzyme. We recently reported the characterization of biliary metabolites of DAPM using various spectroscopic techniques[13]. DAPM was found to be converted by phase I and II biotransformation generating N-oxidation, hydroxylation, acetylation, glucuronic acid and glutathione conjugation products. The interesting biotransformations of these reactive and novel metabolites prompted us to decipher their fragmentation pathways observed in tandem mass spectrometry experiments under collision-induced dissociation (CID). Our assignments, and mechanistic interpretations of product ion spectra of these DAPM metabolites should prove useful in future characterizations of other aromatic amine metabolites.

Experimental Details

Animal

Bile duct-cannulated Sprague-Dawley rats were dosed with vehicle (ethanol) or 25/50 mg/kg DAPM; bile was collected for 6 hours on ice and then stored immediately at −80 °C. To remove the protein, aliquots of bile (20–50μL) were thawed and filtered using Microcon 10,000 MW centrifugal filters (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX). Before the samples were injected into LC/MS, they were kept on ice.

Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry

The samples were separated on a reversed-phase HPLC column (Waters XTerra-MS C18, 1 × 150 mm, 3μm) by a gradient solvent system consisting of solvents A (10 mM ammonium acetate pH 3.5) and B (Acetonitrile). The percentage of mobile phase B was maintained at 15% for the first 2 min with the flow rate set at 50μL/min, and then ramped linearly to 35% over the next 33 min. The proportion of B was increased to 90% over the next 15 min. Aliquots of filtered bile (20 μL) were injected onto the column and directly delivered into the electrospray LCQ Deca Xp Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan, San Jose, CA) that was operated in the positive ion mode. The metabolites were first detected in a LC-MS survey scan, and the most abundant ion found during each survey scan was then selected to be fragmented using the data-dependent acquisition mode. The six most abundant MS2 fragments were automatically selected to acquire ensuing MS3 spectra. To cut down on redundant data acquisition, dynamic exclusion was enabled at the following settings: repeat counts = 2, repeat duration = 0.3 min, exclusion duration = 0.4 min, and exclusion mass width = 3 Da. The temperature of the ion transfer capillary was maintained at 275°C and the electrospray needle was operated at 3.2 kV. Tandem mass spectra were obtained with a mass window of 3 Da, relative collision energy set at 38%, and an activation time of 5–30 msec.

Results and Discussion

As described previously,[13] biliary metabolites of DAPM have been observed using LC-radioisotope detection. Either off-line (fraction collection) or on-line LC/MS was carried out with mass spectrometric characterization of the metabolites. M1–M9 appeared at m/z 375, 532, 403, 475, 24, 417, 478, 574 and 517 Da, respectively. Of the nine metabolites, M2 and M7 are the most intriguing and complicated metabolites. Both involve N-oxidation and hydroxylation of the parent DAPM compound, along with glutathione conjugation on M2, or glucuronic acid and glycine adduction on M7. Although structural characterizations were accomplished on both metabolites via various spectroscopic techniques,[13] their detailed fragmentation mechanisms based upon MSn data are presented here for the first time.

Metabolite M2

During LC-MS analysis, M2 is observed as a protonated molecule [M+H]+ at m/z 532 with a retention time of 7 min (Fig. 1b). The product ion spectrum of M2 is shown in Fig. 2a. Major product ions of the protonated M2 precursor correspond to loss of the pyroglutamate moiety (−129) leading to the base peak at m/z 403, or loss of the glycine moiety (−75), thereby generating a fragment ion at m/z 457. Those neutral losses are characteristic of glutathione adducts during CID experiments. Two additional fragments at m/z 308 and 179 correspond to protonated glutathione (thiol form) and protonated cysteinyl-glycine, respectively. The appearance of these four characteristic fragment ions allowed the identification of M2 as a GSH adduct. In addition, fragment ions at m/z 385, 439 and 514 were formed via H2O loss from m/z 403, 457 and 532, respectively. Glutathione conjugation is proposed to occur at the imine nitrogen atom based on the absence of an N-H proton and the presence of a full complement of aromatic ring protons (i.e., 8) in the 1H-NMR spectrum. Assignment of the hydroxylated form of the DAPM methylene bridging carbon resulting from phase I metabolism of the M2 precursor was deduced[13] from 1H-NMR and TOCSY spectra, and the predicted chemical shift of the hydroxyl proton calculated using Chemoffice Ultra 2004 software (Cambridgesoft Corporation, Cambridge, UK).

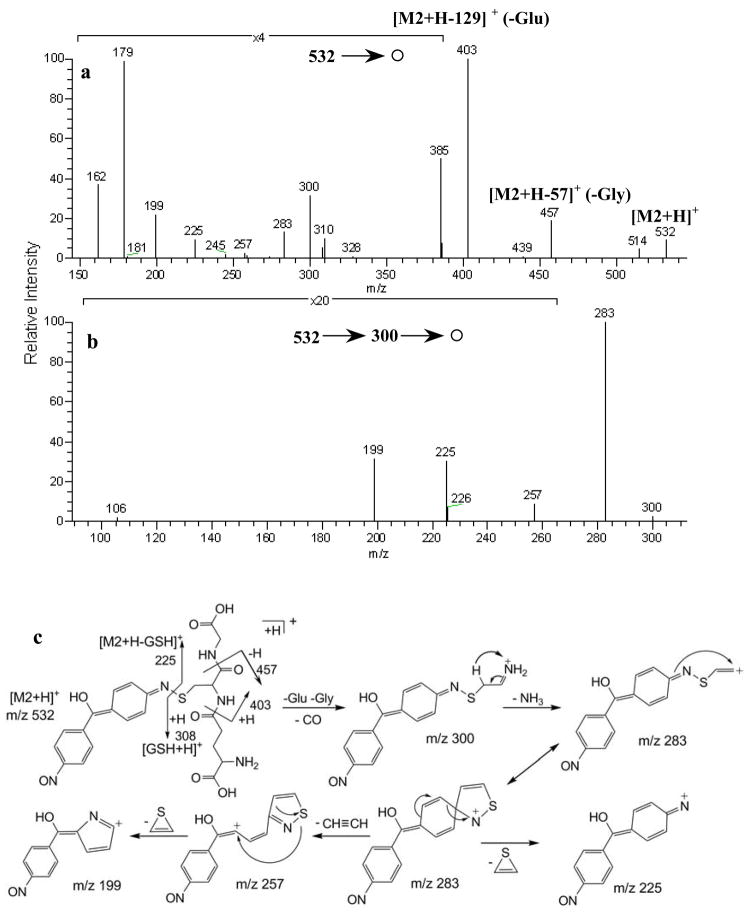

Fig. 2.

(a) MS/MS spectrum of protonated M2 at m/z 532 and (b) MS3 spectrum of m/z 300; (c) proposed fragmentation pathways of protonated M2 and m/z 300

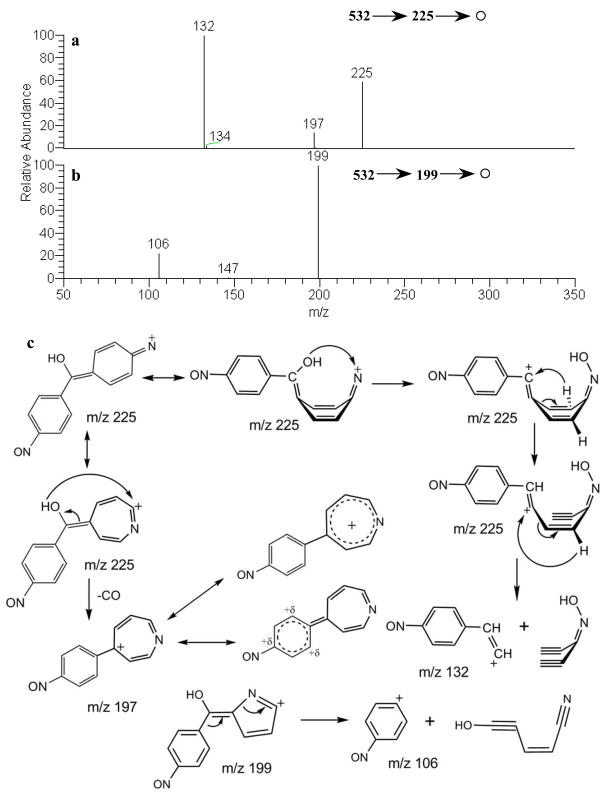

Even though solid evidence of glutathione conjugation was readily derived from LC-MS/MS, little information about the xenobiotic moeity was directly obtainable from MS2 spectra because cleavages occurred primarily at or on the GSH moiety. To enhance the amount of structurally-informative fragmentation, the data dependent MS3 data acquisition method was employed on mass spectral peaks appearing in the low m/z range (m/z 200–400) which represent fragments with charge retention on the xenobiotic moiety. These informative fragments appeared at m/z 199, 225, 257, 283 and 300 in the MS/MS spectrum (Fig. 2a), and they were subjected to further fragmentation. The MH+-232 fragment at m/z 300 (Fig. 2c) was formed via successive eliminations of pyroglutamic acid, glycine residues and CO from protonated M2.[14] A further elimination of NH3 led to the fragment ion at m/z 283 (Fig. 2b). The fragment ions at 199, 225 and 257 were produced from the ion m/z 283 ion formed by the cleavage of m/z 300 (Fig. 2b); proposed fragmentation pathways are shown in the Fig. 2c. Additional fragments at m/z 132 and 197 were derived from MS3 decompositions of m/z 225 (Fig. 3a), and the corresponding cleavage mechanisms are shown in the Fig. 3c. The formation of m/z 197 is proposed to occur via rearrangement and elimination of CO (28 Da) with the driving force being production of a highly resonance-stabilized ion shown in Fig. 3c. The MS/MS spectrum of m/z 199 gave a fragment at m/z 106 (Fig. 3b), representing the 4-nitrosophenyl moiety and thus presenting evidence of N-oxidation at one amino group of DAPM. The above interpretation leaves the other (non-nitroso) nitrogen as the only remaining site on M2 available for GSH adduction.

Fig. 3.

MS3 spectra of the precursor ions at: (a) m/z 225; and (b) m/z 199 derived from protonated M2 present in bile of a rat dosed with DAPM; (c) corresponding fragmentation pathways

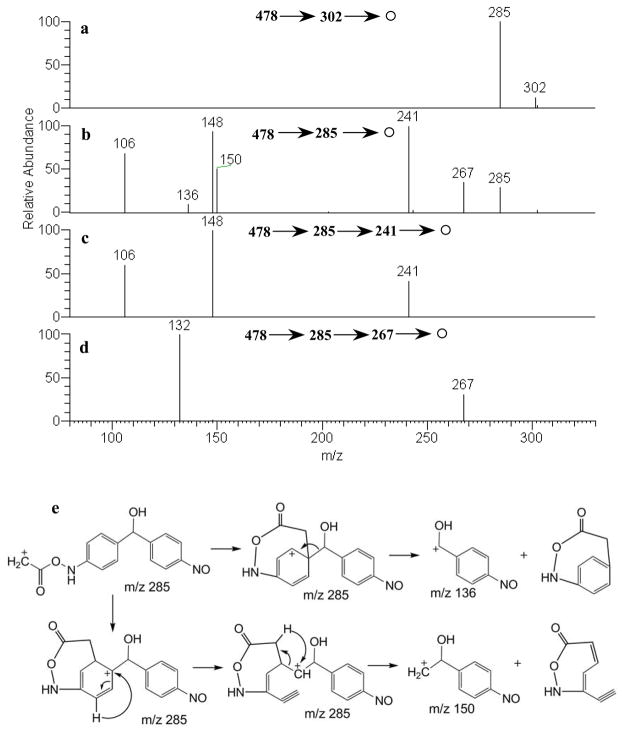

Metabolite M7

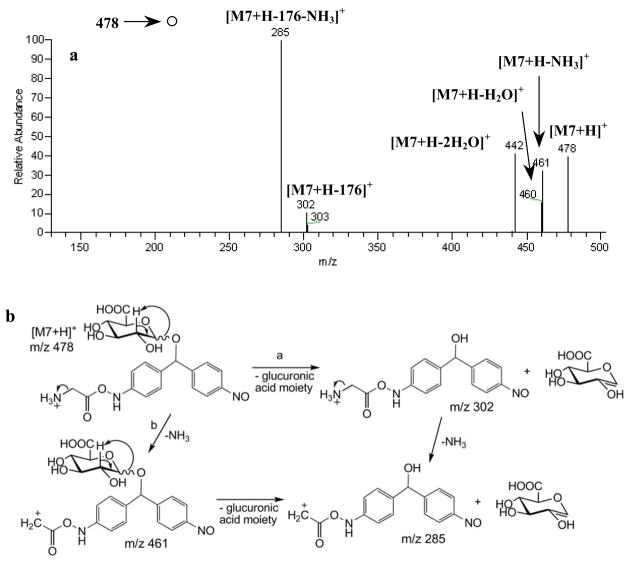

M7, eluting at an LC-MS retention time of 21 min (Fig. 1c), appeared as the protonated molecule [M+H]+ at m/z 478. In the MS/MS spectrum (Fig. 4a), the protonated M7 precursor underwent a 176 Da (-anhydroglucuronic acid) loss characteristic of a glucuronide to generate the product ion at m/z 302. H2O losses to form the fragment ions at m/z 460 (-H2O) and 442 (-2H2O) (Fig. 4a) were also visible. The MS3 spectrum of m/z 302 gave a product ion at m/z 285 corresponding to NH3 loss (Fig. 5a). The above mentioned characteristic glucuronide loss (−176 Da) could also occur in conjunction with NH3 loss (−17 Da) from the m/z 478 precursor to give m/z 285 (Fig. 4a), and the corresponding mechanisms are proposed in Fig. 4b. The MS3 spectrum of m/z 285 (Fig. 5b) yielded: m/z 106, 136, 148, 150, 241 and 267. The fragmentation pathways leading to m/z 136 and 150 are shown in Fig. 5e.

Fig. 4.

(a) MS/MS fragmentation of protonated M7 at m/z 478; (b) proposed fragmentation pathways leading to the fragment ions at m/z 285, 302 and 461

Fig. 5.

MS3 spectra of: (a) m/z 302 and (b) m/z 285; MS4 spectra of: (c) m/z 241; and (d) m/z 267; (e) proposed fragmentation pathways of m/z 285 leading to the fragment ions at m/z 136 and 150

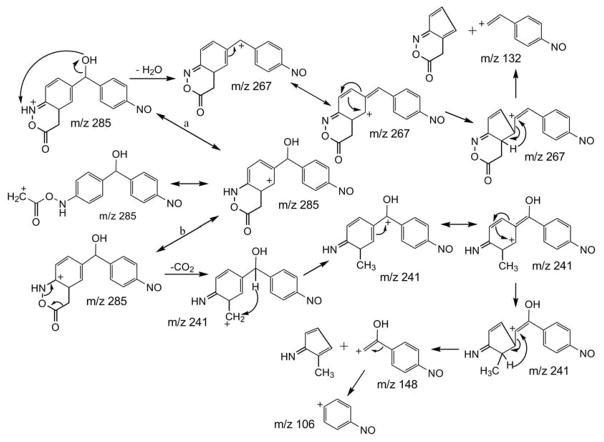

The monoisotopic mass of M7 appears at an even m/z value, indicating that it contains an odd number of nitrogen atoms based on the “nitrogen rule”. The possibility of amino acid conjugation with one of the free amines of DAPM can account for both the mass increase, and the addition of a third nitrogen. There are two well-established metabolic pathways of amino acid conjugation with xenobiotics containing primary aromatic amine functional groups. One is through reaction of the amino acid carboxylic acid group with a free amine on the xenobiotic to form an amide bond, such is exemplified by glutamic acid conjugation with acetaminophen metabolites.[15] Secondly, xenobiotics containing a hydroxylamine group may conjugate with the carboxylic acid group of amino acids such as proline or serine.[16] This is accomplished when aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase activates the amino acid and then conjugates it with hydroxylamine to form an N-ester that can be degraded into an electrophilic nitrenium ion.[17] The MS3 loss of 44 Da from the precursor ion at m/z 285 gave the product ion at m/z 241(Fig. 5b), that we have assigned as CO2 loss. Observation of this prominent CO2 loss indicates that an N-ester (-N-O-C(O)-) had been formed rather than an amide (-N-C(O)-) bond (Fig. 6). In our search of the literature, we were unable to find previous examples of this type of glycine conjugation to aromatic hydroxyl amines (with glycyl- t-RNA synthetase participation). MS4 of m/z 241 gave the product ions at m/z 106 and 148 (Fig. 5c), representing 4-nitrosobenzyl and its precursor (Fig. 6). The appearance of m/z 106 indicated N-oxidation at the other free amine group of DAPM. The fragment ion at m/z 148 suggested hydroxylation on the methylene bridging carbon of DAPM (Fig. 6). Under CID, m/z 285 also underwent H2O loss to form a fragment ion at m/z 267 (Fig. 5b), corroborating the postulation that hydroxylation had occurred on the methylene carbon. The MS4 spectrum of m/z 267 showed a fragment ion at m/z 132 (Fig. 5d), and the corresponding pathway is shown in Fig. 6. Because both amine groups of DAPM have been metabolized, the only reasonable site for glucuronic acid conjugation is with the hydroxyl oxygen on the bridging carbon. Thus the structure of M7 can be confidently identified.

Fig. 6.

Proposed fragmentation pathways leading to the MS3 product ions at m/z 241 and 267, and the MS4 product ions at m/z 106, 132 and 148

Conclusion

The structural assignments of these metabolites from rat bile are mainly based on LC-tandem mass spectrometry data. MSn spectra up to MS4 were acquired for the thorough structural elucidation that forms the basis for this paper. Detailed interpretation of MSn spectra is essential to eliminating ambiguity in deducing metabolite structures. A combination of metabolic processes was involved in transforming DAPM into the M2 and M7 metabolites found in rat bile. These biotransformations include glutathione, glycine and glucuronic acid conjugation (phase II) of DAPM that had previously undergone hydroxylation and N-oxidation (phase I). They demonstrate that DAPM is susceptible to (phase I) conversion to electrophilic species that can be trapped by phase II metabolism. The existence of phase I reactive metabolites of DAPM supports the postulation that reactive intermediates are involved in the toxicity of DAPM, possibly implicating covalent protein adducts that were also found in rat bile.[13] Further studies are in progress to characterize those DAPM modified proteins.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0518288, CHE-0630427), the Louisiana Board of Regents (HEF(2001-06)-08), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32 ES07254, 1F32 ES05892, and ES06348).

References

- 1.Scott TS. Carcinogenic and Chronic Toxic Hazards of Aromatic Amines. Elsevier Monographs; Amsterdam: 1962. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radomski JL. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1979;19:129–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.19.040179.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanzlik RP, Koen YM, Theertham B, Dong Y, Fang J. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:95–100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouris CS. Dyestuffs. 1963;44:287–299. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore WM. Methylenedianiline. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1978. p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopelman H, Robertson MH, Sanders PG, Ash I. Br Med J. 1966;1:514–516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5486.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanz MF, Kaphalia L, Kaphalia BS, Bomagnoli E, Ansari GA. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;117:88–97. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90221-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanz MF, Wang A, Campbell GA. Toxicol Lett. 1995;78:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03251-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt P, Burck D, Weigmann HJ. Z Gesamte Hyg. 1974;20:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen K, Dugas TR, Cole RB. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:728–734. doi: 10.1002/jms.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocker J, Boobis AR, Davies DS. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1998;17:161–167. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200170303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kautiainen A, Wachtmeister CA, Ehrenberg L. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:614–621. doi: 10.1021/tx9701485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen K, Cole RB, Cruz VS, Blakeney EW, Kanz MF, Dugas TR. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baillie TA, Davis MR. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:319–325. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutlib AE, Shockcor J, Espina R, Graciani N, Du A, Gan L. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:735–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klaassen CD. Casarett & Doull’s Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. 6. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato R, Yamazoe Y. Drug Metab Rev. 1994;26:413–429. doi: 10.3109/03602539409029806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]