Abstract

Rotator cuff tears are disabling conditions that result in joint loading changes and functional deficiencies. Clinically, damage to the long-head of the biceps tendon has been found in conjunction with rotator cuff tears and this damage is thought to increase with increasing rotator cuff tear size. Despite its importance, controversy exists regarding the optimal treatment for the biceps. An animal model of this condition would allow for controlled studies to investigate the etiology of this problem and potential treatment strategies. We created rotator cuff tears in the rat model by detaching single (supraspinatus) and multiple (supraspinatus+infraspinatus or supraspinatus+subscapularis) rotator cuff tendons and measured the mechanical properties along the length of the long-head of the biceps tendon four and eight weeks following injury. Area of the biceps was increased in the presence of a single rotator cuff tendon tear (by ~150%), with a greater increase in the presence of a multiple rotator cuff tendon tear (by up to 220%). Modulus values decreased as much as 43% and 56% with one and two tendon tears, respectively. Also, multiple tendon tear conditions involving the infraspinatus in addition to the supraspinatus affected the biceps tendon more than those involving the subscapularis and supraspinatus. Finally, biceps tendon mechanical properties worsened over time in multiple rotator cuff tendon tears. Therefore, the rat model correlates well with clinical findings of biceps tendon pathology in the presence of rotator cuff tears and can be used to evaluate etiology and treatment modalities.

Introduction

Rotator cuff tears are painful and disabling conditions that result in joint loading changes and functional deficiencies.1 Shoulder injuries rank third in musculoskeletal clinical visits after back and neck pain, and tears of the rotator cuff are thought to occur in up to 50% of the population over age 65.2 While most rotator cuff tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon, only half of those tears are isolated in that one tendon.3 Clinically, damage to the long-head of the biceps tendon has been found in conjunction with rotator cuff tears and this damage is thought to increase with increasing rotator cuff tear size.4 Clinical observations have described the biceps tendon as being widened and flattened at the time of rotator cuff repair.5 Biceps tendon pathology is thought to be a significant source of pain and can be treated with tenotomy or tenodesis even when the rotator cuff tear is too massive for repair.

Unfortunately, most clinical studies are not able to address the underlying cause of biceps tendon changes in the presence of rotator cuff tears in a controlled manner and cadaveric studies cannot monitor the injury process with time. Currently, no animal models are available on this topic. Therefore, the objective of our study was to develop and utilize such an animal model to investigate the mechanical property changes in the long-head of the biceps tendon following one and two tendon rotator cuff tears in an established rat model.6 We hypothesized that: 1) An increase in the number of rotator cuff tendons torn would result in decreased mechanical properties of the long-head of the biceps tendon; 2) These mechanical properties would continue to decrease over time; and 3) A supraspinatus+infraspinatus tendon tear would result in lower mechanical properties than a supraspinatus+subscapularis tendon tear. Development and utilization of a biceps tendon injury model in the presence of a rotator cuff tear could have important implications in shoulder research and clinical understanding.

Materials and Methods

Seventy-eight Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, 400–450g) were used in this study approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were divided into 4 groups sacrificed at 4 and 8 weeks after detachment: uninjured (n=10 at 4 wks, n=10 at 8 wks), supraspinatus tendon detachment (n=10 at 4 wks, n=10 at 8 wks), combined supraspinatus+infraspinatus tendon detachment (n=10 at 4 wks, n=9 at 8 wks), and combined supraspinatus+subscapularis tendon detachment (n=9 at 4 wks, n=10 at 8 wks). In the tendon detachment groups, a unilateral surgery was performed to sharply detach the prescribed rotator cuff tendon(s) from the bony insertion.7 Similar to the established surgical model of supraspinatus tendon detachment in the rat8, that technique has been expanded to include additional detachment of the infraspinatus or subscapularis tendons

Briefly, with the arm in external rotation, a 2 cm skin incision was made followed by blunt dissection down to the rotator cuff musculature. The rotator cuff was exposed and the tendons were visualized at their insertion on the humerus. The tendons were identified as the subscapularis, the most anterior and broadest rotator cuff tendon, the supraspinatus, which passes under the bony arch comprised of the acromion, coracoid and clavicle, and the infraspinatus, posterior to the others and with an insertion similar to the supraspinatus. Suture was passed under the acromion to apply upward traction for further exposure and the supraspinatus was separated from the other rotator cuff tendons before sharp detachment at its insertion on the greater tuberosity using a scalpel blade. In the two-tendon detachment groups, the other tendon (either subscapularis or infraspinatus) was detached in the same manner with a sharp dissection from the insertion site. Any remaining fibrocartilage at the insertion was left intact and detached tendons were allowed to freely retract without attempt at repair creating a gap ~4 mm from their insertion sites. The overlying muscle and skin were closed and the rats were allowed unrestricted cage activity.

After sacrifice, the scapula and the long-head of the biceps tendon were removed. The associated muscle was removed, and the tendons were fine dissected under a microscope. Five Verhoeff stain lines were then placed along the length of each tendon using 6-0 silk suture. The first stain line was placed at the tendon insertion onto the scapula and the remaining stain lines were place at 1.5, 3.5, 8.5 and 11.5 mm from the insertion, denoting the proximal tendon insertion site (0–1.5mm), the portion of the tendon in the intra-articular space (1.5–3.5mm), and the portion in the bicipital groove (3.5–8.5mm), respectively (Figure 1). A fifth stain line was placed at 11.5mm to identify grip placement and these stain lines were used to determine the distribution of strain along the length of the tendon. While the aspect ratio of each individual portion may be considered small, the grip to grip distance was 11.5mm and as a result, we do not anticipate any effect on our strain measurements. These positions were determined from dissection of two rats, where the length and position of the bicipital groove was determined. Two additional shoulders (same strain, size, gender) were fixed, embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were examined under a light microscope and the length of the insertion site was measured with UTHSCSA ImageTool.

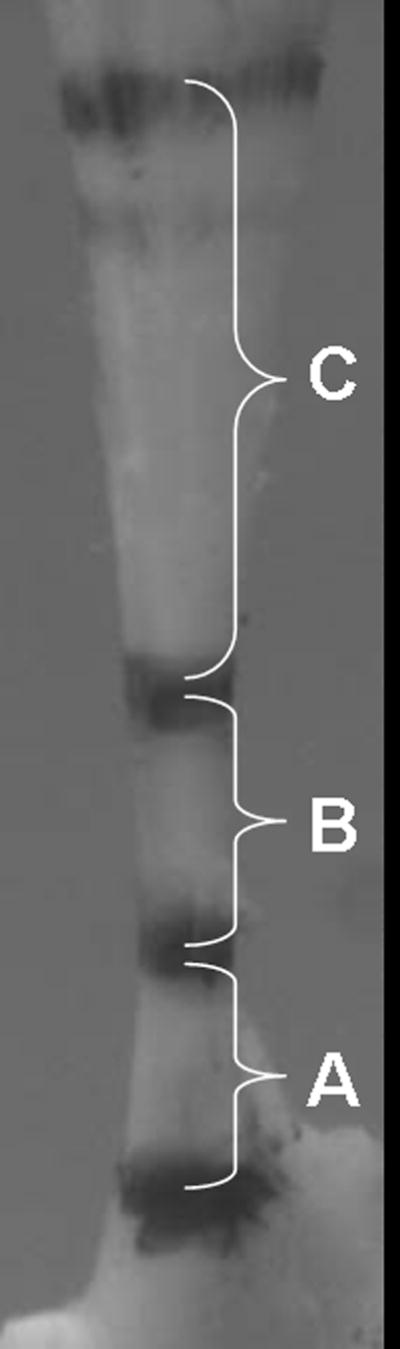

Figure 1.

Image obtained during biomechanical testing illustrating regions of biceps tendon denoted by stain lines. A-insertion site, B-intra-articular space, C-bicipital groove.

Tendon geometry was measured in each tendon portion using a laser based system.9 Briefly, a CCD laser was used in combination with 2 LVDTs to acquire thickness and x- and y- displacements (system’s accuracy is 0.05mm2). Three passes across the width were taken at equidistant intervals in each portion of the tendon. A custom program was then utilized to calculate the average tendon area in each location. This software plots cross-sectional ‘slices’ and constructs an interpolated mesh (with 0.05 mm spacing) between them that represents the specimen volume. The average cross-sectional area of each portion is then calculated from this image.

For biomechanical testing, the scapula was embedded in a holding fixture using polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). The holding fixture was inserted into a specially designed testing fixture. The proximal end of the tendon was then held at the fifth stain line (11.5mm) in a screw clamp lined with fine grit sandpaper. The specimen was then immersed in a 39°C PBS bath, preloaded to 0.1N, preconditioned for 10 cycles from 0.1N to 0.5N at a rate of 1%/sec, and held for 300sec. Immediately following, a stress relaxation experiment was performed by elongating the specimen to a strain of 4% at a rate of 5%/sec (0.575 mm/sec) followed by a 600sec relaxation period. Specimens were then returned to the initial preload displacement and held for 60 seconds. Ramp to failure was then applied at a rate of 0.3%/sec.

Using the applied stain lines, local tissue strain in each tendon portion was measured optically with a custom program (MATLAB). This program determines the difference in gray scale intensity between the stain line and the surrounding tendon and can detect differences of 1–1.5 pixels. The optical strain measurement is accurate to 8–12% of the measurement, which for this study translates to 1–1.5% strain. Elastic properties, such as stiffness and modulus were calculated using linear regression from the visually determined linear region of the load-displacement and stress-strain curves, respectively. This practice has been verified in our laboratory and was found to be no different using an automated program to determine the linear region. Maximum stress at the insertion site was calculated only for specimens that failed at the insertion site and was not calculated for specimens that failed in any other manner, for instance in the tendon midsubstance or at the grip. As measures of viscoelastic properties, peak and equilibrium load and percent relaxation were determined from the stress relaxation curve for each specimen.

Significance was assessed between groups at each time point with one-way ANOVAs and a Bonferroni correction. Since control tendons exhibited a difference between time points, a bootstrapping approach was used to pair 4 week and 8 week data from each group (control, supraspinatus tendon detachment, supraspinatus+infraspinatus tendon detachment, and supraspinatus+subscapularis tendon detachment).10 The difference in each property from 4 to 8 weeks was then compared between groups using a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction. To correct for the number of comparisons, significance was set at p<0.0125 (0.05/4) and trends at p<0.025 (0.1/4).

Results

Four weeks after tendon detachments, biceps tendon areas in all locations were higher in the supraspinatus and supraspinatus+infraspinatus detachment groups when compared to control (Table 1). Biceps tendon areas in the supraspinatus+subscapularis group were increased over control in the intra-articular space and bicipital groove (Table 1). Interestingly, biceps tendons in the presence of a supraspinatus tendon tear were larger than those in the presence of a supraspinatus+subscapularis tear at this time point (Table 1). At the insertion site, a supraspinatus+infraspinatus tendon tear resulted in a larger biceps than a supraspinatus+subscapularis tear (Table 1). Insertion site modulus of the biceps tendon was decreased with a supraspinatus tear compared to control and supraspinatus+subscapularis groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biceps area and modulus values at the insertion site, intra-articular space, and bicipital groove are increased compared to control at both 4 and 8 weeks post detachment.

| Time post detachment (weeks) | Insertion Site Area (mm2) | Intra-Articular Space Area (mm2) | Bicipital Groove Area (mm2) | Insertion Site Modulus (MPa) | Intra-Articular Space Modulus (MPa) | Bicipital Groove Modulus (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 | 0.79±0.19 | 0.58±0.14 | 0.61±0.10 | 202±95 | 267±90 | 313±51 |

| 8 | 054±0.05 | 0.37±0.04 | 0.47±0.07 | 281±82 | 451±117 | 632±155 | |

| Supra Detach | 4 | 1.16±0.35* | 0.96±0.20* | 0.87±0.13* | 115±66# | 235±159 | 312±159 |

| 8 | 1.08±0.25* | 0.95±0.19* | 0.89±0.13* | 243±144 | 284±167* | 454±159* | |

| Supra+Subscap detach | 4 | 0.90±0.20‡ | 0.75±0.17†,# | 0.73±0.17#,‡ | 193±56† | 312±155 | 344±154 |

| 8 | 1.09±0.18* | 0.87±0.08* | 0.74±0.06*,† | 185±69* | 217±91* | 466±161# | |

| Supra+Infra detach | 4 | 1.09±0.21*,## | 0.84±0.19* | 0.81±0.14* | 152±66 | 245±80 | 321±117 |

| 8 | 1.45±0.44*,‡,## | 1.19±0.21*,†,‡‡ | 1.06±0.26*,‡‡,‡ | 133±80* | 195±71* | 366±193* |

sig from control,

trend from control,

sig from supra detachment,

trend from supra detachment,

sig from supra+subscap detachment,

trend from supra+subscap detachment

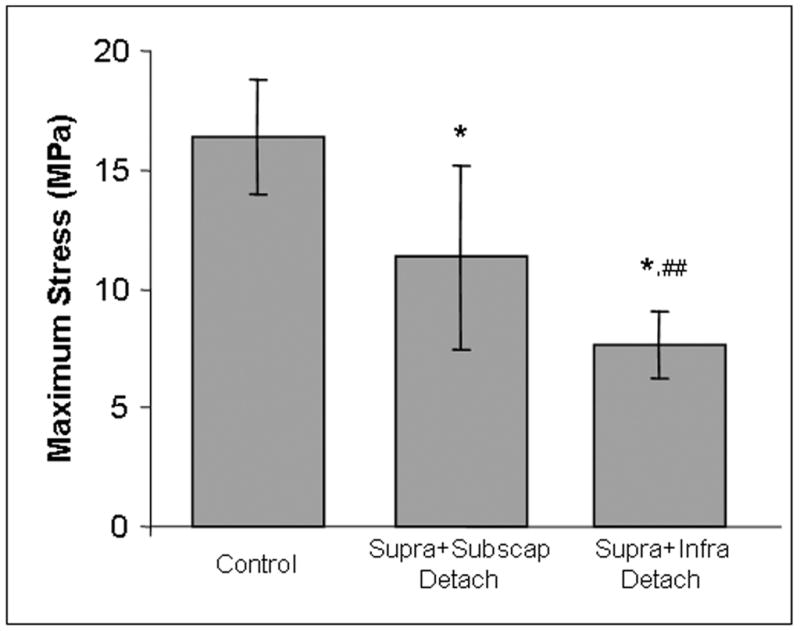

Eight weeks after surgery, biceps tendons from the one and two tendon detachment groups had significantly larger areas in all three locations compared to control tendons (Table 1). Modulus of the tendon in the intra-articular space and bicipital groove were decreased in all detachment groups compared to control tendons (Figure 2). Maximum stress and insertion site modulus from the two tendon detachment groups were significantly decreased compared to control tendons (Figures 2,3). Interestingly, tendons from the supraspinatus only detachment group did not fail at the insertion site, therefore maximum stress could not be calculated. There was a trend for larger area values in the two tendon detachment groups compared to the one tendon detachment group (Table 1). Finally, long-head of the biceps tendons from the supraspinatus+infraspinatus tendon detachment group had a larger area in all portions of the tendon (Table 1) and lower maximum stress (Figure 3) compared to tendons from the supraspinatus+subscapularis tendon detachment group.

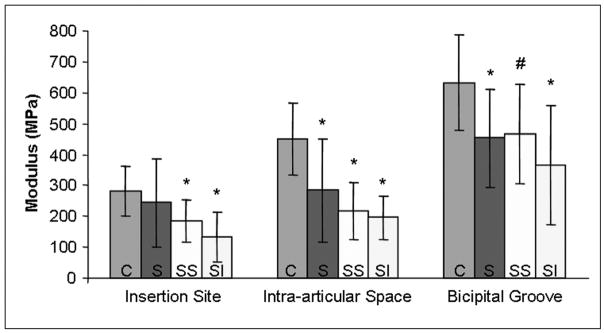

Figure 2.

Biceps modulus at the insertion site, intra-articular space and bicipital groove is decreased in rotator cuff tendon tear groups 8 weeks following detachment. C-control, S-supraspinatus detachment, SS-supraspinatus+subscapularis detachment, SI-supraspinatus+infraspinatus detachment. (*=sig from control, #=trend from control)

Figure 3.

Maximum stress of the biceps tendon is decreased with two-tendon tears and is further decreased with the involvement of the infraspinatus as opposed to the subscapularis. (*=sig from control, ##=trend from supra+subscap detachment)

Between 4 and 8 weeks, the areas of all three tendon portions increased for both two-tendon groups compared to control (Figure 4). In addition, the area of the biceps tendons in the supraspinatus+infraspinatus group was also higher than in the supraspinatus group in all 3 portions and higher than the supraspinatus+subscapularis group in the intra-articular space and bicipital groove (Figure 4). The tendon modulus was also lower in all three locations compared to control for both the supraspinatus+infraspinatus and supraspinatus+subscapularis tear groups (Figure 5).

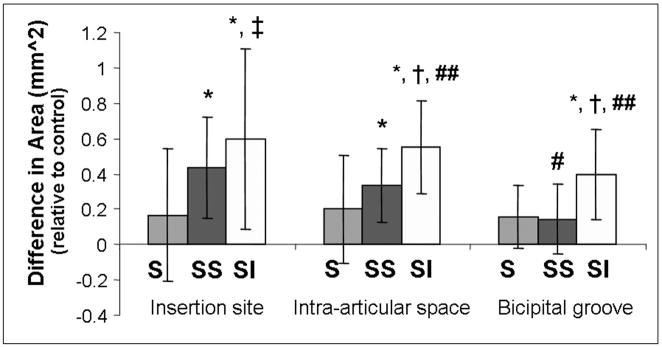

Figure 4.

The change in area from 4 to 8 weeks, presented relative to control, is significantly higher in the two-tendon detachment groups when compared to control at the insertion site, in the intra-articular space and in the bicipital groove. (*=sig from control, #=trend from control, †=sig from supra detachment, ‡=trend from supra detachment, ##=trend from supra+subscap detachment)

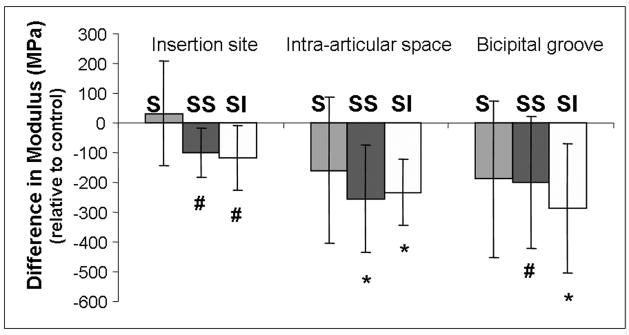

Figure 5.

Biceps tendon modulus, presented here relative to control, decreased between 4 and 8 weeks in both the supraspinatus+subscapularis and supraspinatus+infraspinatus groups compared to control. (*=sig from control, #=trend from control)

Discussion

This is the first animal study to examine the long-head of the biceps tendon after one and two rotator cuff tendon detachments. Results support our first hypothesis that mechanical properties of the long-head of the biceps tendon would decrease with increasing rotator cuff tear size. This finding agrees with several clinical studies that note a widened or frayed biceps at the time of rotator cuff repair.5 Clinical studies have also shown increasing biceps tendon lesions with multiple rotator cuff tendon tears.4 Changes in biceps tendons in the presence of rotator cuff tears may be due to altered joint loading scenarios including use as a humeral head depressor, functional compensations, or stress shielding due to disuse. Degeneration of the biceps tendon in the presence of a rotator cuff tear may be due to the role of the biceps as a humeral head stabilizer, which would be enhanced with a tear, or subacromial impingement. It could also be the result of the biceps tendon being required to perform new functions with altered mechanical loading at the shoulder when the tendons that would normally perform those functions are damaged or no longer present. It is also interesting to note that biceps tendons in the presence of a supraspinatus tear did not fail at the insertion site. Tendons in this group exhibited an increase in area but no decrease in insertion modulus. This could mean that with a supraspinatus tear alone, the biceps tendon quality has not yet become substantially altered.

Our second hypothesis was also supported in that biceps tendon area and modulus significantly worsened over time in both two tendon detachment groups, despite the spread in the data. This result correlates with a clinical study which found that all biceps tendons with cuff tears considered “chronic” (those over 3 months) had associated pathology.4 At four weeks, changes were primarily in tendon area. This correlates with clinical findings of an inflamed tendon.11 However, clinical studies cannot measure mechanical properties of these tendons and it is not known if the tendon tissue has become degenerate, nor its time course. In our study, we measured a progression from a tendon with increased area at 4 weeks to a tendon with increased area and decreased modulus at 8 weeks. We also found that biceps tendons in the presence of two-tendon rotator cuff tears degenerated significantly between 4 and 8 weeks, as shown by increased area and decreased modulus. This degeneration with time is supported by other studies in our laboratory that have shown supraspinatus only tendon tears to be mostly healed by 8 weeks8, while multiple tendon tears continue to have decreased mechanical properties at this time (unpublished data). This increase in degeneration with time may also be due in part to a self-limitation in use or a functional loss by the rat at early time points. Previous studies in our laboratory have evaluated functional changes by measuring rat ambulation parameter post-injury. In these studies, we have found that rat ambulation was altered up to 4 weeks post supraspinatus detachment.12 Rat ambulation was further altered with 2 tendon tears, and this alteration persisted up to 8 weeks (unpublished data). In addition, we also have found that the mechanical properties of the uninjured rotator cuff tendons are altered 413 and 8 (unpublished data) weeks after single and multiple tendon tears, which may be due to changes in shoulder kinematics. With time, remaining tendons would learn to compensate for functions normally performed by detached tendons, resulting in further decreases in mechanical properties.

Finally, our third hypothesis was supported as a supraspinatus+infraspinatus tear had decreased mechanical properties compared to a supraspinatus+subscapularis tear. This expectation was based on clinical data suggesting biceps tendonitis following the involvement of the infraspinatus tendon in rotator cuff tears as well as the biceps role as a humeral head depressor when two superior stabilizers (supraspinatus and infraspinatus) are torn. Following four weeks post rotator cuff tears, only the area of the biceps insertion site was increased with an infraspinatus tear as opposed to a subscapularis tear. However, at 8 weeks all 3 areas as well as maximum stress of the biceps tendon were significantly worse in the supraspinatus+infraspinatus group. While both two tendon tears got progressively worse over time, areas in the supraspinatus+infraspinatus group progressed significantly more than the supraspinatus only and supraspinatus+subscapularis tear groups.

It is also interesting to note that the tendon modulus varied along the length of the tendon. The modulus was lowest at the insertion site, increased in the intra-articular space and was highest in the bicipital groove. This could be due to the different functions and loading environments seen in each of these areas. This reiterates the general concept that the material properties of tendon vary depending on location and that average whole tissue properties may not be an accurate representation of each portion of the tissue. While the small relative size of several tendon portions may be considered a limitation in this study, our system to measure strain optically can detect differences of 1–1.5 pixels. At the insertion site, the smallest region, the average pixel change in control tendons was 12.7 pixels, which is well within the sensitivity or our system. We are therefore confident that the differences in modulus between regions are accurate.

The use of a quadruped animal to model the human shoulder may be considered a limitation of this study. While we acknowledge that the rat is not an exact model of the human condition, as no model of any human disease or injury ever is, it has been widely used and published for over 10 years. While the forces in the biceps tendon in the rat and human are both unknown, the rat shoulder has comparable shoulder musculature, bony anatomy, articulations and motion providing support for its use. It should be acknowledged that the rotator cuff tendon tears in this study were made acutely and do not represent the most common human condition where degeneration is thought lead to tendon rupture. Biceps tendon changes however, do develop over time as they are thought to be due to the changes in joint kinematics and altered loading that result from rotator cuff tears. Clinically, these changes would occur slowly over time and not instantaneously as in this study. Also, the addition of a later time point would be interesting to see if degeneration of the biceps tendon in this model leads to eventual tendon rupture.

The results of this study are important because they define the rat rotator cuff injury model as consistent with the biceps tendon pathology seen clinically with rotator cuff tears. The role of the biceps tendon is not well characterized and there is some debate to the extent of its function.1 Some clinicians believe that the biceps tendon has little function and therefore retaining an abnormal biceps tendon in the presence of a rotator cuff tear will affect functional outcome more than the loss of that tendon, but no clinical studies have been done to address this theory.14 The identification of an animal model of biceps tendon pathology with rotator cuff tears allows for controlled studies to investigate the etiology of this problem as well as potential treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH and NSF for funding.

References

- 1.Burkhead WZ, Arcand Michel A, Zeman Craig, Habermeyer Peter, Walch Giles. The Biceps Tendon. In: Rockwood CA, editor. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1998. pp. 1009–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomoll AH, Katz JN, Warner JJ, Millett PJ. Rotator cuff disorders: recognition and management among patients with shoulder pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3751–3761. doi: 10.1002/art.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harryman DT, 2nd, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Matsen FA., 3rd The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CH, Hsu KY, Chen WJ, Shih CH. Incidence and severity of biceps long head tendon lesion in patients with complete rotator cuff tears. J Trauma. 2005;58:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000170052.84544.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoi E, Hsu HC, Carmichael SW, et al. Morphology of the torn rotator cuff. J Anat. 1995;186 (Pt 2):429–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, et al. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:383–392. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. San Diego, CA: 2007. The effect of tear size on the mechanical properties of the remaining intact tendons in a rat rotator cuff model; p. 1163. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Mehta S, et al. Supraspinatus tendon organizational and mechanical properties in a chronic rotator cuff tear animal model. J Biomech. 2004;37:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favata M. Bioengineering PhD Thesis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2006. Scarless healing in the fetus: Implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soslowsky LJ, Thomopoulos S, Esmail A, et al. Rotator cuff tendinosis in an animal model: role of extrinsic and overuse factors. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:1057–1063. doi: 10.1114/1.1509765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthi AM, Vosburgh CL, Neviaser TJ. The incidence of pathologic changes of the long head of the biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:382–385. doi: 10.1067/mse.2000.108386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry SM, Reidich BJ, Peltz CD, et al. Rat ambulation alterations due to supraspinatus tendon detachment. ASME Summer Bioengineering Conference; Amelia Island Plantation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. San Diego: 2007. The effect of tear size on the mechanical properties of the remaining intact tendons in a rat rotator cuff model; p. 1163. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahrens PM, Boileau P. The long head of biceps and associated tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1001–1009. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]