Abstract

Alterations in the function of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaM Kinase II) have been observed in both in vivo and in vitro models of epileptogenesis; however the molecular mechanism mediating the effects of epileptogenesis on CaM Kinase II have not been elucidated. This study was initiated to evaluate the molecular pathways involved in causing the long lasting decrease in CaM Kinase II activity in the hippocampal neuronal culture model of low Mg2+ induced spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges (SREDs). We show here that the decrease in CaM kinase II activity associated with SREDs in hippocampal cultures involves a Ca2+/N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent mechanism. Low Mg2+ induced SREDs results in a significant decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation of the synthetic peptide autocamtide-2. Reduction of extracellular Ca2+ levels (0.2 mM in treatment solution) or the addition of DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) 25 µM blocked the low Mg2+ induced decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation. Antagonists of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/kainic acid receptor or L-type voltage sensitive Ca2+ channel had no effect on the low Mg2+ induced decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation. The results of this study demonstrate that the decrease in CaM kinase II activity associated with this model of epileptogenesis involves a selective Ca2+/NMDA receptor-dependent mechanism and may contribute to the production and maintenance of SREDs in this model.

Index Words: phosphorylation, seizures, status epilepticus, magnesium

1. Introduction

Seizures occur when there is a loss of the ability of the central nervous system to regulate neuronal activity resulting in synchronous discharges of a population of neurons (Lothman et al., 1991). Epilepsy is the condition whereby a state of altered neuronal plasticity is manifested by the presence of spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges (SREDs, seizures). The process responsible for the transformation of neuronal populations from normal neurophysiological function to the development of SREDs is called epileptogenesis. The cellular mechanisms which underlie the process of epileptogenesis and the establishment of SREDs are still poorly understood. The Ca2+ ion functions as one of the primary second messenger systems in the CNS and is involved in regulating many cellular processes involved in development, maintenance and plasticity of neuronal function (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995). In contrast to its physiological role in cellular function, excessive influx of Ca2+ can result in neurotoxicity (Choi, 1988). Alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis have been observed during both the induction and maintenance of epileptiform seizures (Pal et al., 2000; Pal et al., 1999; Pal et al., 2001; Raza et al., 2004; Raza et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2004) and has been shown to be dependent on an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor pathway (DeLorenzo et al., 1998; Delorenzo et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2002). Studies from this laboratory have provided evidence that prolonged elevations in hippocampal neuronal intracellular Ca2+ following brain injury cause epileptogenesis in the neurons that survive the injury (DeLorenzo, et al., 2005). Thus, it is important to evaluate possible Ca2+ - dependent mechanisms that may play a role in mediating epileptogenesis.

Ca2+ /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaM kinase II) is a multifunctional enzyme that acts to mediate many Ca2+-dependent neuronal processes (Bronstein et al., 1993) and plays a major role in modulating neuronal excitability and function (Bading et al., 1993; DeLorenzo, 1981; 1983; Goldenring et al., 1986; McGlade-McCulloh et al., 1993; Sakakibara et al., 1986; Soderling, 1993). The multi functional role of CaM Kinase II in neuronal processes is underscored by both its broad distribution throughout the CNS and high level of expression which comprises 0.5–1.0% of total brain protein and up to 2% of hippocampal protein (Erondu and Kennedy, 1985). Modulation of CaM kinase II has been shown to be associated with a number of models of neuro excitation which include LTP (Barria et al., 1997), glutamate-induced excitotoxicity (Churn et al., 1995), seizures (Blair et al., 1999; Bronstein et al., 1988; Murray et al., 1995; Perlin et al., 1992; Singleton et al., 2005) and epilepsy (Bronstein et al., 1992; Butler et al., 1995; Churn et al., 2000a; Churn et al., 2000b). Thus, understanding the role of CaM kinase II in epileptogenesis may provide additional insight into the molecular basis for the induction of SREDs.

This study was initiated to determine if the decrease in CaM kinase II activity observed in the hippocampal neuronal culture model of SREDs was dependent on Ca2+ and activation of the NMDA receptor during epileptogenesis. Furthermore, experiments were carried out to evaluate the possible contribution of selective receptor systems to the loss in CaM kinase II activity in this preparation. The hippocampal neuronal culture model of SREDs involves treating primary rat hippocampal neuronal cultures in a low Mg2+ environment for 3 h resulting in the induction of continuous seizure activity for the duration of the exposure regimen. Upon reintroduction of normal media containing Mg2+, the continuous seizure activity ceases and the emergence of a permanent plasticity change, evidenced by the expression of SREDs, continues for the life of the culture preparation. This in vitro model of epileptiform seizure activity is well suited to biochemical and electrophysiological investigations to elucidate the cellular mechanisms that underlie epileptogenesis and the SREDs activity associated with epilepsy. Using this model of acquired epilepsy, this study provides the first direct evidence that the NMDA receptor/Ca2+ pathway plays an important role in causing the decrease in CaM kinase II activity observed following epileptogenesis in the hippocampal neuronal culture model of SREDs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Minimum Essential Media (MEM: containing Earle’s salts with 25 mM HEPES and no L-glutamine) and trypsin were obtained from Invitrogen-Gibco Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum was obtained from Atlanta Biological (Atlanta, GA). Progesterone and corticosterone were obtained from ICN (Costa Mesa, CA). Gamma- [32P] ATP (10 ci/mMol) was obtained from DuPont-NEN (Boston, MA). Autocamtide-2 and tetrodotoxin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). DL-2-Amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV), 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) disodium and 2,3-Dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline- 7-sulphonamide (NBQX) disodium were obtained from Tocris Cookson Inc. (Ellisville, MO). CytoScint™ scintillation fluid was obtained from Fischer Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures

All animal use protocols were in strict accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines and were approved by the International Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University. Primary hippocampal cultures were prepared by a modification of the method of Banker and Cowan (1979) as described by Sombati et al. (1991). Briefly, hippocampi from 2-day postnatal Sprague-Dawley rat pups were dissected out from the brain and prepared for tissue culture by 0.25% trypsin digestion followed by trituration through a Pasteur pipet. Triturated cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion analysis using a hemocytometer. Glial beds were established by plating at a density of 1 × 105 per 35 mm plate (Nalge Nunc International, USA) and maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum. After 2 weeks, neurons were plated onto confluent glial beds at a density of 2 × 105/35 mm plate. One day following plating, neuronal cultures were treated with 5 µM cytosine arabinoside to inhibit mitotic glial cell proliferation. This culture technique significantly reduced the presence of glial cells in the culture. Hippocampal cultures were maintained in MEM containing an N3 supplement media. The N3 supplement contained 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 2 mM glutamine, 5 µg/ml insulin, 100 µg/ml transferrin, 100 µM putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite, 20 nM progesterone, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1% ovalbumin, 20 ng/ml triiodothyronine and 40 ng/ml corticosterone. Both hippocampal cell cultures and glia beds were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2/95% air. Hippocampal cultures were grown up for 2 weeks prior to experimental manipulation.

2.3. Low Mg2+ treatment of hippocampal neuronal cultures

After two weeks, neuronal cultures were utilized for experimentation. Maintenance media was replaced with physiological recording solution with or without MgCl2 containing (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, .002 glycine, pH 7.3, and adjusted to 325mOsm with sucrose. Thus, low Mg2+ treatment was carried out with physiological recording solution without added MgCl2, while sham controls were treated with physiological recording solution containing 1 mM MgCl2. Unless indicated as low Mg2+ treatment, experimental protocols in this study utilized physiological recording solution containing 1 mM MgCl2. Selected treatment conditions were also carried out with low Mg2+ in the presence of various pharmacological agents which included 25 µM APV, 10 µM CNQX, 10 µM NBQX and 5 µM nifedipine. Stock solutions of pharmacological agents were dissolved in ddH2O, with the exception of nifedipine dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, to make a 1000X concentrated solution and diluted accordingly in physiological recording solution for treatment. For the low Ca2+ condition, physiological recording solution was adjusted to contain 0.2 mM CaCl2. Briefly, after removal of maintenance media, cell cultures were treated by washing gently with 3 × 1.5 ml of appropriate physiological recording solution and then allowed to incubate in this solution for 3 h at 37°C under 5% CO2 95% air. At the end of treatment, cultures were washed gently with 3 × 1.5 ml of MEM at 37 C, returned to maintenance feed and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2/95% air for electrophysiological analysis of epileptiform activity or harvested immediately for biochemical evaluation of kinase activity.

2.4. Electrophysiological analysis of epileptiform activity in hippocampal neuronal cultures

Electrophysiological analysis was performed using previously established procedures in our laboratory (Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). Briefly, cell culture media was replaced with physiological recording solution at 37°C. Cultures were then mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot, Tokyo, Japan), continuously perfused with recording solution and studied using the whole cell current-clamp recording procedure. Patch electrodes with a resistance of 2–4 MΩ were pulled on a Brown-Flaming P-80C electrode puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and then fire polished. For whole-cell current-clamp analysis, the electrodes were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 140 K+ gluconate , 1 MgCl2 and 10 Na-HEPES, ph 7.2, adjusted to 310 ± 5 mOsm with sucrose. Intracellular recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) in whole-cell current-clamp mode. Data were digitized and transferred to video tape using a PCM device (Instrutech, Mineola, NY; 18 kHz sampling frequency) and then played back on a DC-500 Hz chart recorder (Astro-Med Dash II, Warwick, RI).

2.5. CaM Kinase II autophosphorylation

Analysis of CaM kinase II autophosphorylation was conducted as previously described [10]. At specified times post-treatment, hippocampal neuronal cultures were washed twice with physiological solution at 37°C. The wash solution was rapidly replaced with ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 6 mM EDTA, 6 mM EGTA and 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and the cells were immediately scraped from the culture dish surface. The cell suspension was transferred into a glass homogenizer (Kontes, Vineland, NJ), and disrupted with 10 strokes of the homogenizer. Homogenates were normalized for protein using the micro-Bradford reagent assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and studied for endogenous calcium-dependent protein phosphorylation. Standard phosphorylation reaction solutions contained 10–12 µg protein, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 7 µM γ- [32P] ATP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), ±5 mM CaCl2 and ± 600 nM calmodulin. Standard reactions were performed in a shaking water bath at 30°C. After addition γ- [32P] ATP, reactions were allowed to warm to 30°C for 60s and then initiated by the addition of calcium, continued for 60s and then terminated by the addition of 5% SDS STOP solution. Proteins were resolved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and protein bands were visualized by silver-stain as described previously [12]. Stained gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film (XRP-1, Kodak, Rochester, NY) for autoradiography. Autoradiographic images were digitized using HP scanJet 4C/T high resolution scanner with backlighting (Hewlett Packard, Boise, ID). For analysis of autophosphorylation of the 50 and 60 kDa CaM KII protein bands, dried gels were overlayed with their respective autoradiograph and bands on gel were marked, cut and prepared for scintillation counting. Cut gel bands were placed in scintillation vials with 0.25 ml of H2O2 and incubated at 80°C for 120 min. Samples were allowed to cool, placed in CytoScint™ scintillation fluid and measured for incorporation of radioactive phosphate using a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, CA).

2.6. Phosphocellulose assay of CaM kinase II substrate (Autocamtide-2) phosphorylation

Analysis of CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation was conducted as previously described (Blair et al., 1999). Immediately following 3 h of treatment, hippocampal neuronal cultures were washed twice with physiological recording solution at 37°C. The wash solution was rapidly replaced with ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 6 mM EDTA, 6 mM EGTA and 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and the cells were scraped from the culture dish surface. The cell suspension was transferred into a glass homogenizer (Kontes, Vineland, NJ) and disrupted with 10 strokes of the homogenizer. Homogenates were normalized for protein using the micro-Bradford reagent assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules,CA) and studied for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation. Standard phosphorylation reaction solutions contained 6–10 µg protein, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 7 µM γ- [32P] ATP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 20 µM autocamtide-2, ±5 mM CaCl2 and ± 600 nM calmodulin. Standard reactions were performed in a shaking water bath at 30°C. After addition of [32P] ATP, reactions were allowed to warm to 30°C for 60s and then initiated by the addition of calcium, continued for 60s and then terminated by the addition of 20 mM EDTA. For experiments to evaluate contribution of phosphatase 1 and 2A, standard reactions were prepared as above with or without the addition of the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (500 nM), and a reaction time course following addition of calcium which consisted of durations of 30s, 60s, 120s, and 10 min before terminating with the addition of EDTA. Twenty microliters from each stopped reaction solution was immediately blotted onto phosphocellulose (P-81) filter paper (Whatman, Maidstone England) in triplicate. Blotted P-81 filters were then washed 3 times in 50 mM phosphoric acid to remove unincorporated phosphate, rinsed with acetone and allowed to air dry. Washed filters were placed in CytoScint™ scintillation fluid and incorporation of radioactive phosphate was measured using a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, CA).

2.7. CaM kinase II immunoreactivity

To assess the effect of induction of SREDs in hippocampal cultures on protein levels for CaM kinase II, a specific monoclonal antibody for the α subunit of CaM kinase II (Erondu and Kennedy, 1985) was used for Western and slot blot analysis with slight modifications as previously described (Blair et al., 1999). For Western blot analysis, 3 µg of hippocampal culture homogenate protein were resolved on a pre-cast 10% tris-glycine gel on a mini-cell apparatus (Novex® mini, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California) and then transferred onto Immuno-Blot▯ PVDF membrane using a Trans-blot apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For slot blot analysis, 4 µg of homogenate protein were blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane under vacuum filtration using a PR 600 slot blot apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA).

Immunostaining blots on nitrocellulose of α-CaM kinase II with a mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 6G9; 10 µg/ml, 60 min, 25°C) was carried out using a Vectastain▯ ABC alkaline phosphatase staining kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as previously described (Blair et al., 1999). For Western blot analysis, the blot was incubated with the mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 6G9; 10 µg/ml, 60 min, 25°C), following wash, the blot was then incubated with anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000, 45 min, 25°C, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). Staining of α-CaM kinase II protein bands were visualized using ECL (Pierce Inc. Rockford, IL) onto Kodak X-Omat Blue XB-1 X-ray film (Kodak Rochester, NY). Protein and antibody concentrations for both Western and slot blot analysis have been previously determined to be in the linear range for α-CaM kinase II detection (Blair et al., 1999). Film images and stained slot blots were digitized and grey-scale images (8-bit) were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH public domain).

2.8. Statistics

Data were presented as mean ± S.E.M. either as a percent of control or relative intensity where indicated. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Holm-Sidak post-hoc test where appropriate utilizing SigmaStat analysis software (SysStat Software Inc., San Jose, CA); P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Low Mg2+-exposure evokes status epilepticus-like activity with subsequent establishment of SREDs and decrease in activity of CaM Kinase II in hippocampal neuronal cultures

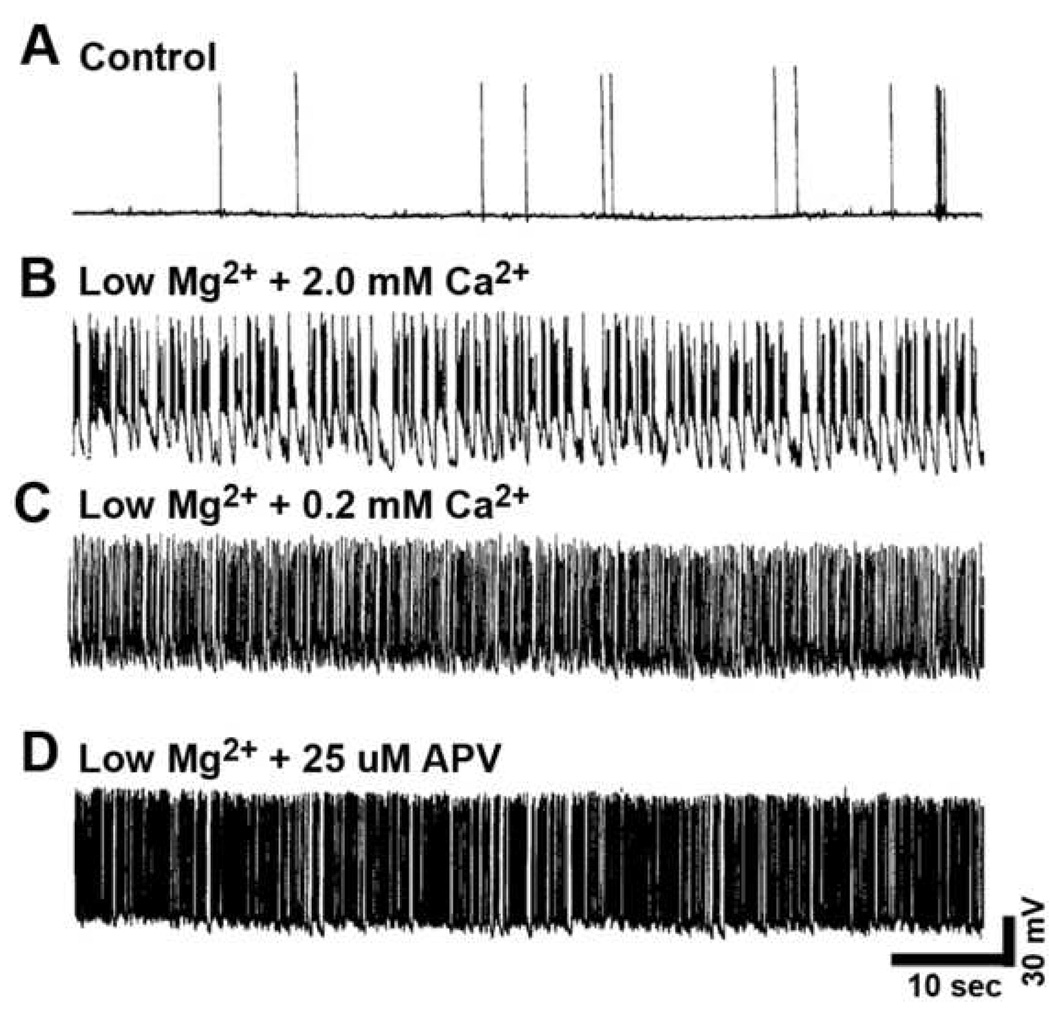

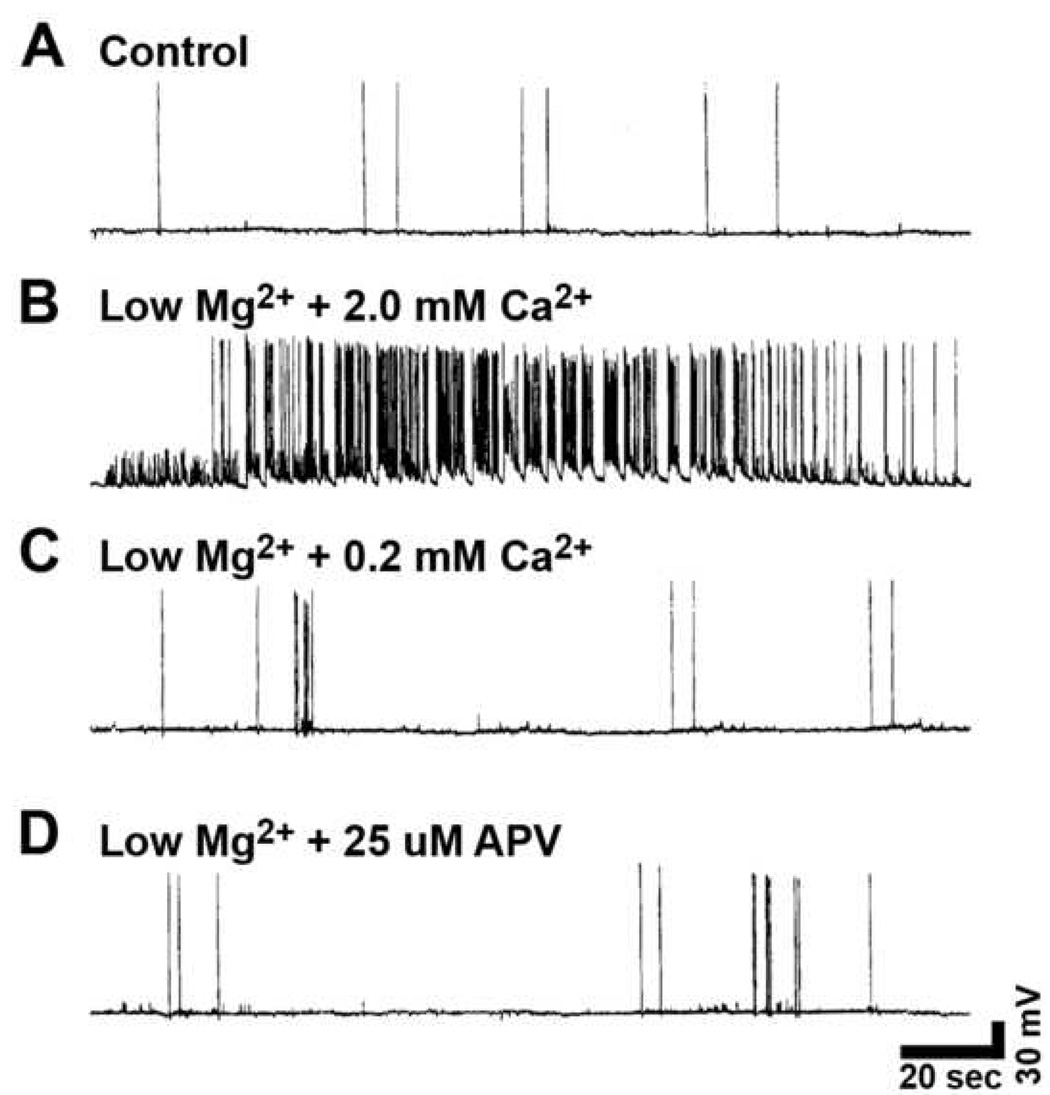

Whole-cell current-clamp analysis of a representative neuron during a 3 h exposure to physiological recording solution containing 1 mM MgCl2 (control) revealed normal baseline activity displaying both excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs and IPSPs) with the generation of occasional action potentials (Fig. 1A), while exposure to 3 h of recording solution without added MgCl2 (low Mg2+) results in the expression of continuous high-frequency epileptiform discharges (status epilepticus) (Fig 1B). One day following exposure to low Mg2+ solution results in a permanent plasticity change evidenced by the presence of SREDs (Fig. 2B), while control neuronal cultures never exhibited SREDs (Fig 2A). The SREDs observed in this in vitro model were comprised of multiple paroxysmal depolarization shifts, dependent on neuronal networks in culture and were responsive to blockade by a number of anticonvulsant agents, characteristics of the clinical condition of epilepsy, as shown previously (Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995).

FIG. 1. Whole-cell current-clamp analysis of low Mg2+-induced continuous seizure activity (status epilepticus) for 3 h in hippocampal neuronal cultures with and without the addition of selective neuropharmacological compounds.

(A) Representative control neuron (plus 1.0 mM MgCl2) revealed "normal" baseline recordings with the occasional generation of spontaneously occurring action potentials. (B) Removal of MgCl2 (low Mg2+) from the physiological recording solution resulted in the development of continuous tonic high-frequency burst discharges. Interestingly, (C) Reducing the Ca2+ (0.2 mM CaCl2) or (D) addition of 25 µM APV in the low Mg2+ resulted in increased frequency of burst discharges.

FIG. 2. Whole-cell current-clamp analysis of SREDs in hippocampal neuronal cultures one day following exposure to 3h of low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus in the presence or absence of selective neuropharmacological compounds.

(A) Representative control neuron (plus 1.0 mM MgCl2) revealed "normal" baseline recordings with the occasional generation of spontaneously occurring action potentials. (B) Removal of MgCl2 (low Mg2+) from the physiological recording solution resulted in the development of SRED activity. Expansion of a section of the SRED shows the individual paroxysmal depolarization shifts overlaid with multiple spikes. (C) Reducing the Ca2+ (0.2 mM CaCl2) or (D) addition of NMDA receptor antagonist APV (25 µM) during the low Mg2+ treatment blocked the development of SRED activity.

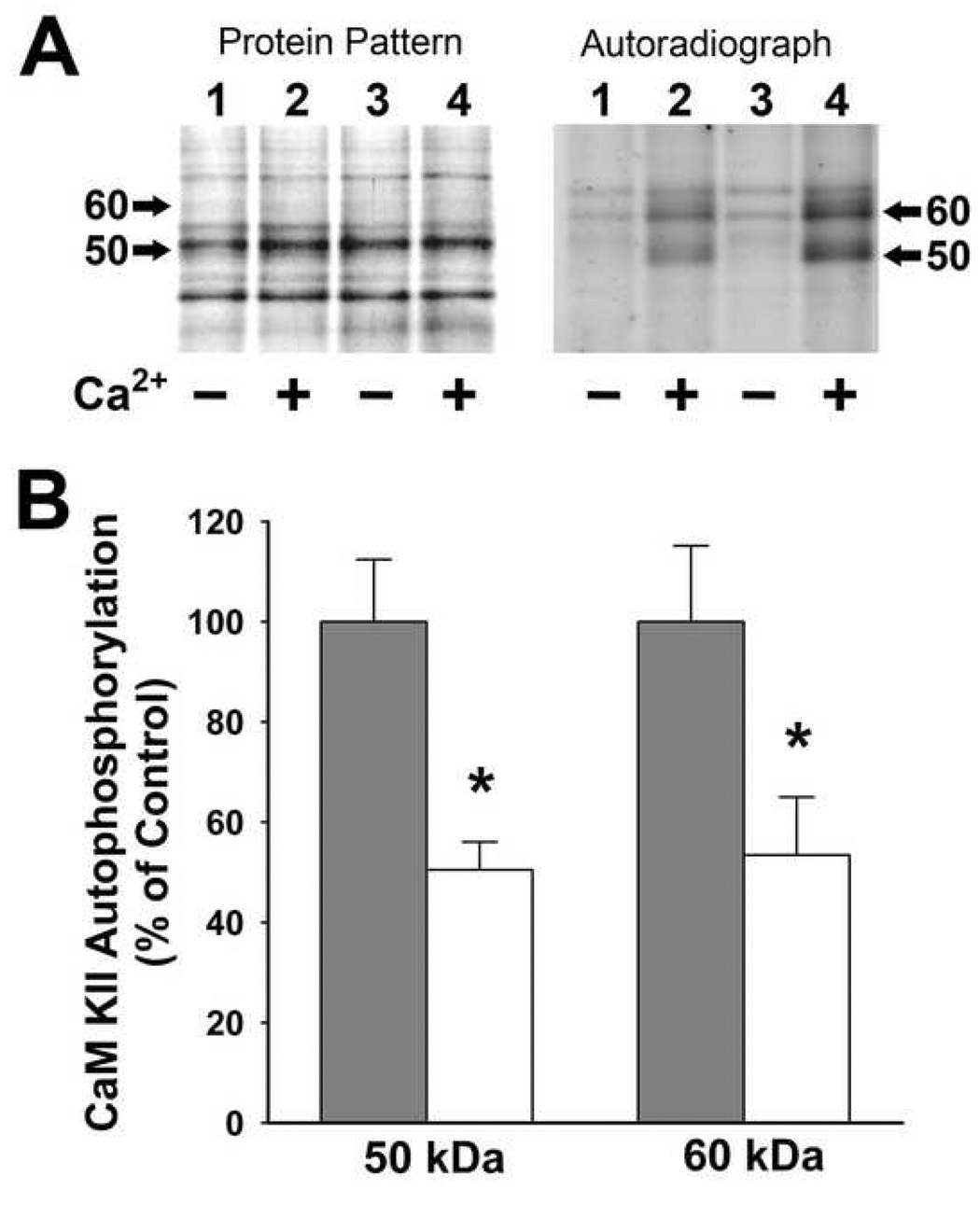

CaM kinase II function was evaluated by endogenous autophosphorylation assays carried out under conditions for basal (Ca2+-independent) and maximal (Ca2+-dependent) CaM kinase II activity. Hippocampal neuronal culture homogenates were prepared from sham control and hippocampal cultures expressing SRED activity one day following low Mg2+ treatment and were utilized for standard phosphorylation analysis (Blair et al., 1999). Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and gels were silver-stained to confirm balanced protein patterns between all samples (Fig. 3A). Autoradiographical analysis of phosphate incorporation into the α (50 kDa) and β (60 kDa) subunits of Cam kinase II demonstrated a dramatic decrease in maximal (Ca2+-dependent) CaM kinase II activity in low Mg2+ treated samples when compared to control (Fig. 3A), while no change was observed in basal (Ca2+-independent) CaM kinase II autophosphorylation. Levels of maximal CaM kinase II-dependent phosphate incorporation into the 50 and 60 kDa subunits was determined by excising the bands from the gel using the autoradiograph as a template and measuring [32P] incorporation by scintillation counting. Induction of SREDs in hippocampal cultures one day following low Mg2+ treatment resulted in a significant decrease in Ca2+-dependent phosphate incorporation into the 50 and 60 kDa subunits of 50.5±5.6% and 53.4±11.5% of sham control respectively (P ≤ 0.01, n = 4–5, Student▯s t-test) (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3. SRED-associated decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent autophosphorylation (endogenous phosphorylation) of the (50 kDa) and (60 kDa) subunits one day following low Mg2+ treatment.

(A) Standard phosphorylation reactions were run with normalized homogenates from control and low Mg2+ treated hippocampal cultures and then resolved on SDS-PAGE, stained and exposed to x-ray film for autoradiographic analysis. Lanes 1–2 represent low Mg2+ treated samples; lanes 3–4 represent control samples. Protein patterns revealed no change in protein bands between control and “epileptic” cultures. The resultant autoradiograph demonstrates the decreased Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent (+) incorporation of 32P-phosphate into the α (50 kDa) and β (60 kDa) subunits of CaM kinase II in association with SREDs (lane 2) when compared to control (lane 4), while no changes in Ca2+-independent incorporation of 32P-phosphate (−) were observed (lanes 1 and 3). The position of the 50 kDa and 60 kDa subunits are denoted by arrows. (B) Measurement of incorporation of 32P-phosphate into the 50 kDa and 60 kDa subunits of CaM kinase II was carried out by excising the bands from the gel using the autoradiograph as a template and measuring [32P] incorporation by scintillation counting. The basal Ca2+-independent phosphorylation counts were subtracted from Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent counts for each sample. Data are expressed as the percent of mean ± S.E.M. of control (n = 5; control, n = 3; Low Mg2+ treated, * P ≤ 0.005; Student's t-test).

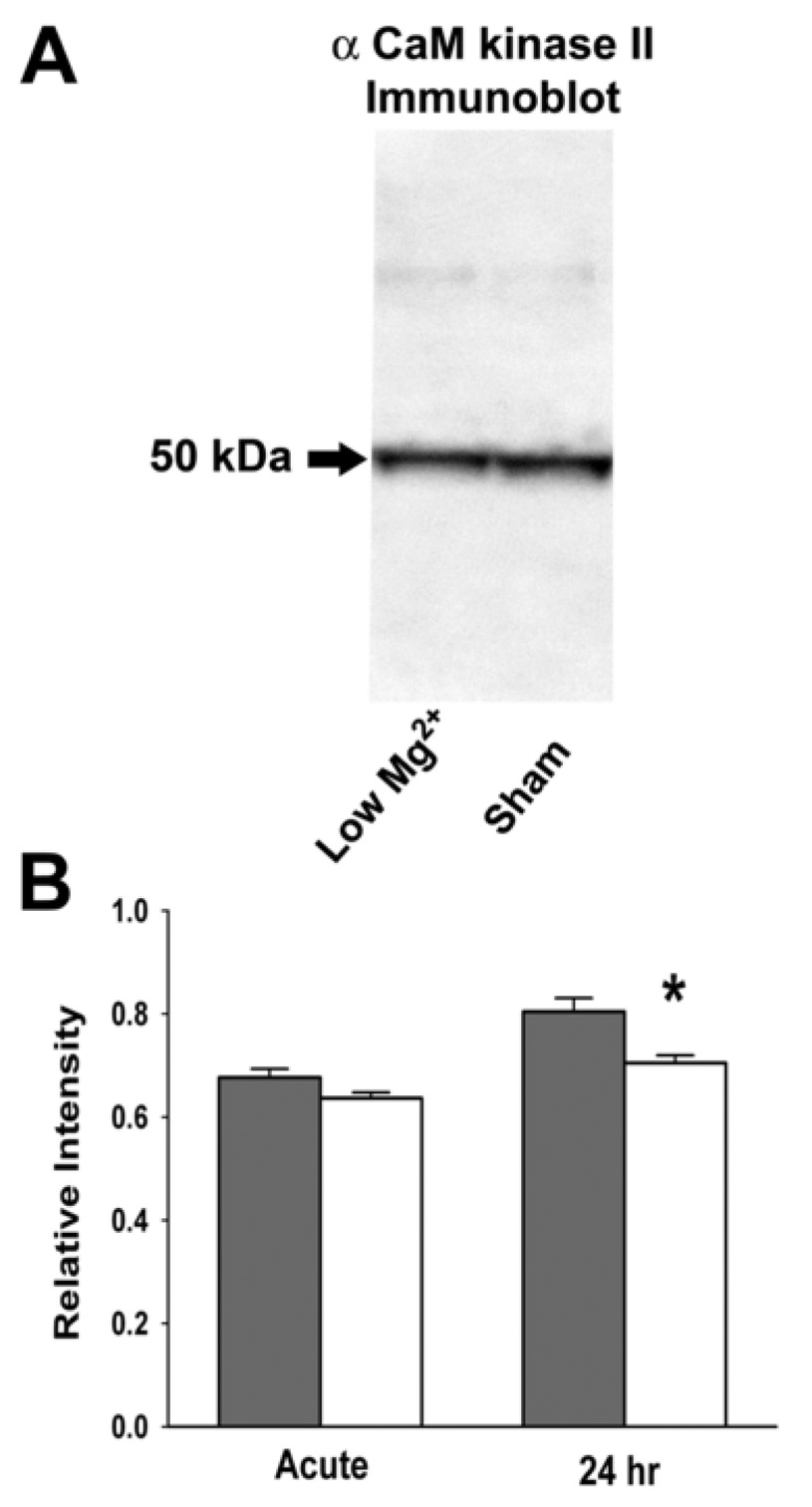

3.2. α-CaM kinase II immunoreactivity

To determine if the effects of induction of SREDs on decreased CaM kinase II activity was mediated by a reduction in CaM kinase II protein expression in low Mg2+ treated hippocampal cultures, levels for the α (50 kDa) subunit were evaluated with monoclonal antibody staining of immunoblots of cell homogenates from sham control and low Mg2+ hippocampal cultures immediately following (acute) and one day post treatment. Western blot analysis was carried out on hippocampal culture homogenates from sham control and low Mg2+ groups one day post-treatment using the mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 6G9) to the α subunit of CaM kinase II (Fig. 4A). Immuno staining revealed a single 50 kDa protein band corresponding to the α subunit which showed a marginal decrease in levels in the low Mg2+ group as compared to controls. For densitometric and statistical analysis, α CaM kinase II protein staining was evaluated on immuno slot blots. Immediately following treatment of hippocampal cultures no significant change in staining was observed, while at one day post-treatment a marginal but significant decrease of 12.4±1.9% (P ≤ 0.01, n = 5, Student▯s t-test) was observed (Fig. 4B). The amount of protein used in the slot blot analysis (4 µg) has previously been demonstrated to be within the linear range for α CaM kinase II antibody staining (Blair et al., 1999). The results indicate that the decrease in CaM kinase II activity was the result of a post translational modification of the kinase, and not due to decreased Cam kinase II expression in the neurons manifesting SREDs.

FIG. 4. α -CaM kinase II immunoreactivity following low Mg2+ treatment of hippocampal neuronal cultures.

(A) Western blot analysis detecting the 50 kDa α subunit of CaM kinase II in Low Mg2+ treated and control hippocampal culture homogenates. Staining with a mouse monoclonal antibody to the α-CaM kinase II subunit revealed a single band at 50 kDa. (B) Densitometric analysis of staining for α CaM kinase II on protein immuno slot blots of homogenates from sham control and low Mg2+ hippocampal neuronal cultures immediately (Acute) and one day (24 hr) following treatment. Data are presented as the mean relative intensity ± S.E.M. (n = 5, *P ≤ 0.05; Student's t-test).

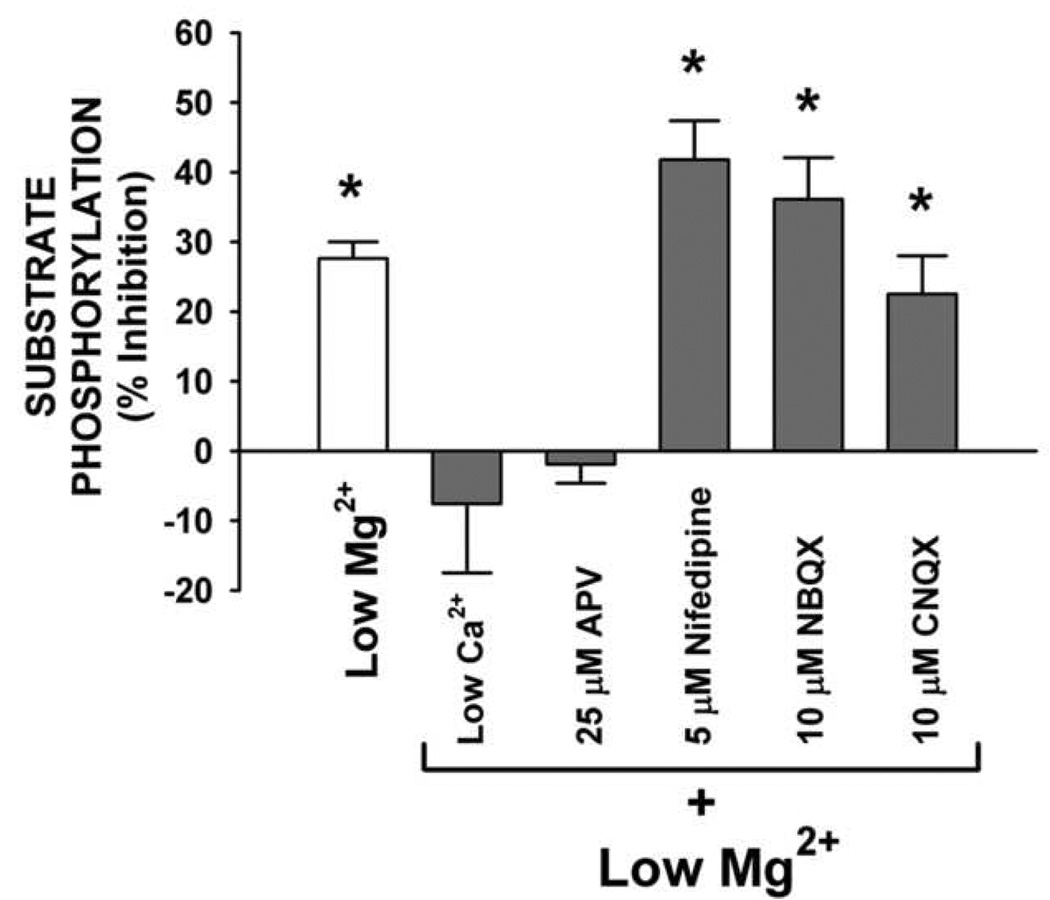

3.3 CaM kinase II-Dependent Substrate Phosphorylation is Decreased Following Low Mg2+ Treatment

To evaluate CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation in hippocampal culture homogenates from sham control and low Mg2+ treated groups, homogenates were used to carry out standard reactions for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of the synthetic peptide autocamtide-2. Following 3 h of low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus, a significant decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation of 27.4±0.5% (P ≤ 0.001, n = 4, Student’s t-test) was observed when compared to control (Fig 6; Low Mg2+). Thus, low Mg2+ treatment of hippocampal cultures results in a decrease in both CaM kinase II-dependent endogenous and substrate phosphorylation in association with the induction of status epilepticus and subsequent expression of SREDs (Fig 1B and 2B respectively).

FIG. 6. CaM kinase II activity immediately following 3 h of low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus with and without the addition of selective neuropharmacological compounds.

Neuronal culture homogenates were assayed for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation of the synthetic peptide autocamtide-2 using the P-81 assay. Low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus (low Mg2+ alone) resulted in a significant decrease in CaM kinase II activity. Reducing CaCl2 to 0.2 mM (Low Ca2+) or addition of NMDA receptor antagonist APV (25 µM) during the low Mg2+ treatment blocked the decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation while the addition of CNQX 10 µM, NBQX 10 µM or nifedipine 5 µM to the low Mg2+ condition had no effect on the low Mg2+-induced decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation. CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation levels for both the low Ca2+ and APV (25 µM) conditions were significantly greater than low Mg2+ alone or low Mg2+ in the presence of nifedipine (5 µM), NBQX (10 µM) or CNQX (10 µM) when evaluated using ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-hoc test (P < 0.001 between all groups). Data for each condition are expressed as a percent mean ± S.E.M. of their respective control (n = 5; Low Mg2+ alone, n = 3; *P ≤ 0.01; Student's t-test when compared to respective control).

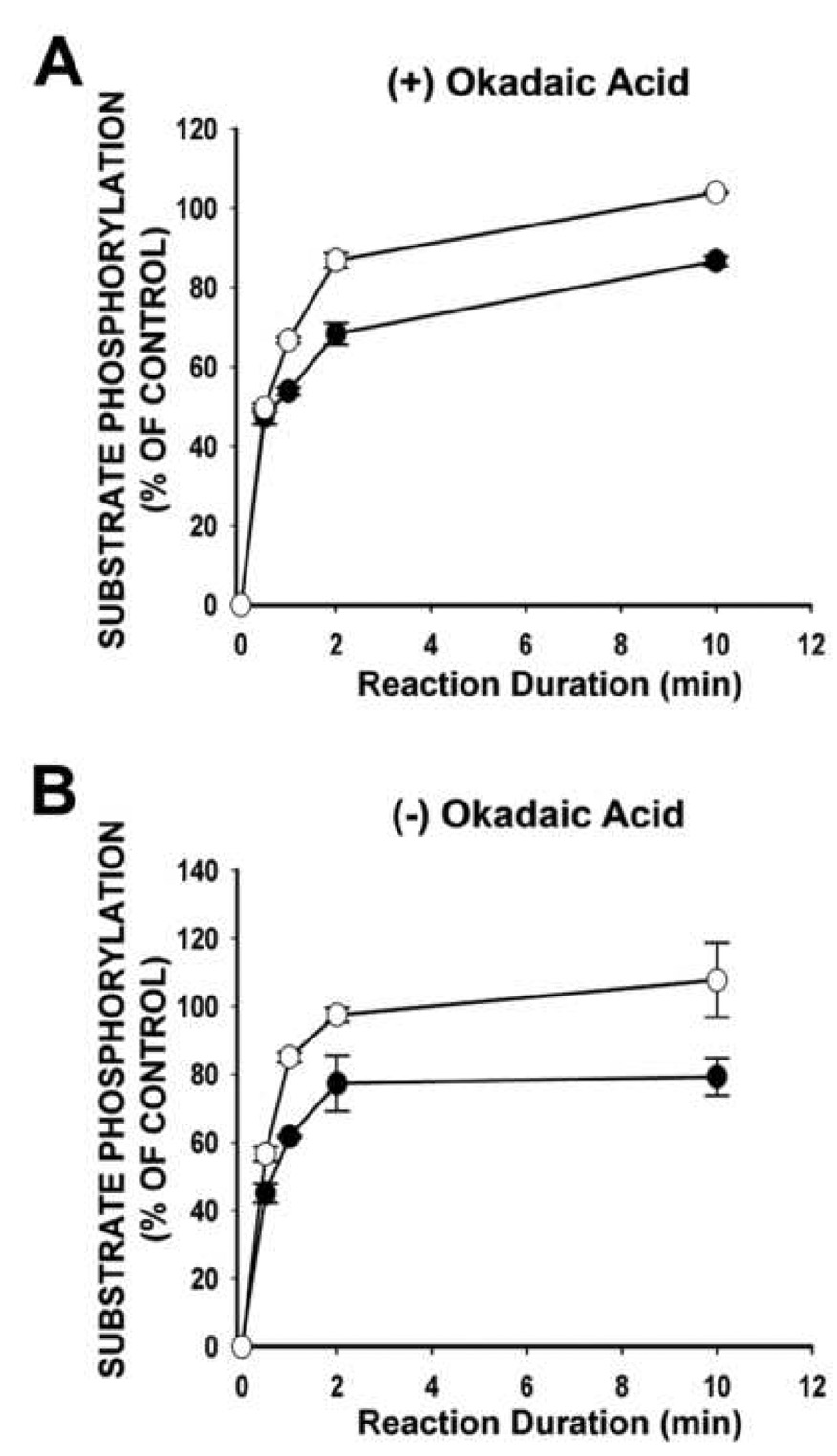

Other mechanisms could contribute to decreased [32P] incorporation into exogenous substrates or the endogenous subunits of CaM kinase II observed with low Mg2+ treatment. Increase in phosphatase activity, with a subsequent increase rate of dephosphorylation, could contribute to an overall decrease in [32P] incorporation as observed with low Mg2+ treated hippocampal cultures in the present study. To determine if a change in phosphatase activity could be contributing to the observed decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation, a reaction time course (30s, 60s, 120s and 10 min) was carried out with (Fig. 5A) and without (Fig. 5B) the phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibitor okadaic acid (500 nM). Inhibition of phosphatase 1 and 2A did not change the observed decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation in low Mg2+ treated hippocampal cultures when compared to controls. These findings demonstrate that the decreased Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation resulting from low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus and subsequent expression of SREDs is not attributed to increased activity of phosphatases 1 and 2A and is the result of a decrease in activity of CaM kinase II.

Fig. 5.

Substrate phosphorylation of the synthetic peptide autocamtide-2 in the presence (A) or absence (B) of the phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibitor okadaic acid (500 nM). Normalized protein samples isolated from hippocampal cultures one day following low Mg2+ treatment underwent a reaction duration time course for standard Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation of autocamtide-2. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of control.

3.4. Induction of SREDs and decrease in activity of CaM Kinase II requires a Ca2+-dependent pathway during Low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus in hippocampal neuronal cultures

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that during 3 h of low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus, hippocampal neurons in culture have a sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels and that this prolonged rise is required for the development of SREDs in this culture preparation (DeLorenzo et al., 1998). Thus, in the present study, we wanted to determine if the prolonged increase in intracellular Ca2+ during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus contributed to the observed decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation in this preparation. Whole-cell current-clamp analysis revealed that reduction of extracellular CaCl2 (low Ca2+) from 2.0 mM to 0.2 mM during the low Mg2+ treatment blocked the expression of SREDs (Fig 2C) with no effect on the intensity or duration of status epilepticus-like activity during the 3 h low Mg2+ treatment (Fig 1C).

Analysis of hippocampal culture homogenates for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation demonstrated that reducing CaCl2 to 0.2 mM (low Ca2+) during the low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus-like activity prevented the decrease in [32P] incorporation as observed in the presence of 2.0 mM CaCl2 (Low Mg2+ alone) (Fig 6). Thus, these findings demonstrate that 3 h of low Mg2+ treatment results in both the expression of SREDs and a decrease in CaM kinase II enzyme activity in hippocampal neuronal cultures, and that these changes are dependent on the prolonged increase in intracellular Ca2+ during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus.

3.5. Induction of SREDs, Ca2+ entry and decrease in activity of CaM Kinase II requires activation of the NMDA receptor system

Calcium entry into neurons can occur via a number of ion channels and receptor systems (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995). Activation of the glutamatergic receptor family can result in influx of Ca2+ into neurons by several different pathways (Delorenzo et al., 2005). The ionotropic NMDA receptor contributes to increases in intracellular Ca2+ by both gating of Ca2+ through its channel pore and by activating voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) by means of membrane depolarization. Furthermore, the glutamatergic AMPA and kainic acid receptors can activate VGCCs, and depending on its receptor subunit makeup, the AMPA receptor can also gate Ca2+ through its channel pore. Furthermore, membrane depolarization, such as that which occurs during of low-Mg2+ induced status epilepticus, can result in activation of L-type and N-type VGCCs. To elucidate what pathway(s) of Ca2+ entry into neurons was involved in the induction of SREDs and altered CaM kinase II activity in association with this preparation, hippocampal cultures were treated with low Mg2+ in the presence of selective pharmacological inhibitors of these receptor/channel systems.

Employing this same model, earlier findings from this laboratory showed that the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist DL-2-Amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) during the low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus resulted in decreasing the sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+ levels by approximately 50% and blocked expression of SREDs (DeLorenzo et al., 1998). In the present study, the presence of 25 µM APV during low Mg2+ treatment of hippocampal neuronal cultures resulted in blocking both the expression of SRED activity (Fig 2D) and the decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation (Fig 6). As observed with lowering Ca2+ to 0.2 mM, the presence of 25 µM APV did not block expression of status epilepticus-like activity during the 3 h treatment with low Mg2+ (Fig 1D). Although the NMDA receptor contributes to only 50% of the increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus in this culture preparation (DeLorenzo et al., 1998), these results indicate that both the long-lived expression of SRED activity (Fig 2D) and decreased Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation (Fig 6) are dependent on NMDA receptor activation. These results demonstrate that the altered function of CaM kinase II and the subsequent expression of SRED activity in this model of epileptiform activity are dependent on a NMDA receptor/Ca2+ transduction pathway.

The AMPA/kainic acid family of glutamate receptors is involved in fast excitatory synaptic transmission in the CNS and mediates influx of Ca2+ through VGCCs (Bettler and Mulle, 1995). Furthermore, the AMPA receptor channel is capable of gating Ca2+ directly when its protein subunit composition is lacking the GluR2 subtype (Dingledine et al., 1999). To evaluate the role that activation of this glutamatergic receptor family and subsequent opening of VGCCs in this in vitro model of epileptiform activity, hippocampal cultures were treated for 3 h with low Mg2+ in the presence of the AMPA/kainic acid receptor antagonists (CNQX 10 µM or NBQX 10 µM) or the VGCC blocker nifedipine (5 µM) and evaluated using both whole-cell current-clamp and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation analysis. Although earlier findings from this laboratory have demonstrated that the addition of either of these AMPA/kainic acid receptor antagonists or VGCC blocker during low Mg2+ treatment resulted in a reducing the status epilepticus-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ by approximately 25% each (DeLorenzo et al., 1998), these agents had no effect on the low Mg2+-induced expression of SRED activity (data not shown). When culture homogenates were assayed for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation, low Mg2+ treatment in the presence of either CNQX (10 µM), NBQX (10 µM) or nifedipine (5 µM) resulted in significant decreases of 22.5±5.5% (P ≤ 0.01, n = 5, Student’s t-test), 36.4±6.0% (P ≤ 0.001, n = 5, Student’s t-test) and 41.8±5.6% (P ≤ 0.001, n = 5, Student’s t-test) respectively when compared to control (Fig 6). Thus, these results indicate that either an AMPA/kainic acid receptor or VGCC transduction mechanism are not involved in low Mg2+-induced decrease in CaM kinase II activity or the expression of SREDs in this hippocampal neuronal culture preparation.

4. Discussion

Utilizing the hippocampal neuronal culture model of SREDs we have demonstrated for the first time that both the enduring expression of epileptiform activity (Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995) and loss in activity of CaM kinase II (Blair et al., 1999) are dependent on a NMDA receptor/Ca2+-dependent mechanism in the same experimental model of acquired epilepsy. Lowering the extracellular Ca2+ level to 0.2 mM CaCl2 or addition of 25 µM APV to block the NMDA receptor channel during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus resulted in blocking both the expression of SRED activity and the decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation. Blockade of the AMPA/kainic acid receptors or L-type VGCC during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus had no effect on the development of SREDs or the decrease in activity of CaM kinase II. Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that during low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus, a sustained elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration gated through the NMDA receptor channel is required for the development of SREDs in this hippocampal neuronal culture model (DeLorenzo et al., 1998). Thus, low Mg2+-induced SREDs is dependent on a NMDA receptor/Ca2+ transduction pathway and is associated with a long-lasting decrease in activity of CaM kinase II (Blair et al., 1999).

Alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis have been observed with a number of models of neuronal excitotoxicity and pathophysiology which include stroke-induced epileptiform discharges (Sun et al., 2004), glutamate-induced neuronal excitotoxicity (Limbrick et al., 2003), ischemia (Parsons et al., 1997), epilepsy (Pal et al., 2001; Parsons et al., 2001; Raza et al., 2004; Raza et al., 2001) and status epilepticus (Pal et al., 1999; Parsons et al., 2000). Furthermore, recent studies utilizing the rat pilocarpine model of status epilepticus-induced acquired epilepsy have demonstrated that a prolonged rise in intracellular Ca2+ occurs in the epileptic state (Raza et al., 2001) and that both epileptogenesis (Rice and DeLorenzo, 1998) and the chronic alteration in Ca2+ homeostasis (Raza et al., 2004) require NMDA receptor activation during the status epilepticus insult. Thus, one proposed mechanism of injury-induced epilepsy (acquired epilepsy) is that an initial Ca2+/NMDA receptor-dependent neuronal insult results in chronic plasticity of Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms which then act to perpetuate the pathophysiological changes that underlie epilepsy (Delorenzo et al., 2005). The results of this study and earlier reports from our laboratory (DeLorenzo et al., 1998) have shown that induction of SREDs in this preparation is dependent on a Ca2+/NMDA receptor pathway and that a lasting change in Ca2+ homeostasis occurs in association with SREDs (Pal et al., 2000).

Alterations in Cam kinase II function have been observed in a number of models of seizure (Blair et al., 1999; Bronstein et al., 1988; Murray et al., 1995; Perlin et al., 1992; Yamagata et al., 2006) and epilepsy (Bronstein et al., 1992; Butler et al., 1995; Churn et al., 2000a; Lee et al., 2001). Both epileptogenesis and the decrease in CaM kinase II activity in the rat pilocarpine model of acquired epilepsy are dependent on NMDA receptor activation during the initial status epilepticus insult (Kochan et al., 2000; Rice and DeLorenzo, 1998) and transgenic modulation of forebrain NMDA receptor structure by inducing expression of the developmental NR2D subunit in mature mouse brain acts to suppress epileptogenesis with electrical kindling (Bengzon et al., 1999). Additionally, the observed long-lived changes in Ca2+ homeostasis in both in vivo (Raza et al., 2004) and in vitro (DeLorenzo et al., 1998) models of acquired epilepsy are dependent on NMDA receptor activation. Finally, recent studies have shown that selective suppression of CaM kinase II function in hippocampal neuronal cultures using antisense oligonucleotide knockdown results in both the induction of SREDs (Churn et al., 2000b) and alteration in Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms (Carter et al., 2006). Thus, these previous findings and the results from the present study suggests a strong association between alterations in both CaM kinase II function and Ca2+ homeostasis with acquired epilepsy, and that these maladaptations may contribute to the pathophysiology evident in these models.

The observed decrease in CaM kinase II function in the present study could result from a number of cellular mechanisms. Although our results indicate a marginal but significant decrease in levels of α CaM kinase II protein one day following low Mg2+ treatment, immediately following 3 h of low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus a significant decrease in CaM kinase II-dependent substrate phosphorylation was observed with no changes in protein levels. Previous findings have shown that a decrease in CaM kinase II expression one day following low Mg2+-induced status epilepticus is likely attributable to a marginal decrease in neuronal culture density and does not totally account for the loss in enzyme function (Blair et al., 1999). Increase in activity of specific protein phosphatases could also account for the decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent endogenous and substrate phosphorylation observed in our study. Phosphatases 1 and 2A have been shown to be primarily responsible for acting on the site of endogenous phosphorylation of CaM kinase II (Shields et al., 1985). Inhibition of phosphatases 1 and 2A in our study did not block the decrease in Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent substrate phosphorylation, suggesting that increased activity of these phosphatases did not contribute to the observed findings of this study. Increased activity of the phosphatase calcineurin has been observed in brain homogenates from pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats (Kurz et al., 2001). Such an increase may contribute to a decrease in phosphate incorporation as observed in this study, although previous work has demonstrated that select inhibition of calcineurin in this preparation did not block the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent decrease in substrate phosphorylation (Blair et al., 1999).

The results from this study further substantiate that an alteration in function of CaM kinase II occurs with seizures and epilepsy, and that this decrease in activity is dependent on a Ca2+/NMDA receptor-dependent pathway. In addition to a number of previous studies, the current findings support the hypothesis that during both epileptogenesis and establishment of acquired epilepsy prolonged alterations in both intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and function of CaM kinase II underlie changes in neuronal plasticity that are associated with the epileptic phenotype. Further studies are warranted to elucidate what specific cellular mechanisms are involved in the induction and maintenance of these maladaptive changes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NINDS grants RO1-NS052529 and RO1-NS051505 to RJD and NIDA P50DA005274 (DA05274 to RJD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bading H, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gene expression in hippocampal neurons by distinct calcium signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.8097060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barria A, Muller D, Derkach V, Griffith LC, Soderling TR. Regulatory phosphorylation of AMPA-type glutamate receptors by CaM-KII during long-term potentiation. Science. 1997;276:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengzon J, Okabe S, Lindvall O, McKay RD. Suppression of epileptogenesis by modification of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit composition. Eur.J.Neurosci. 1999;11:916–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettler B, Mulle C. Review: neurotransmitter receptors. II. AMPA and kainate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:123–139. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00141-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RE, Churn SB, Sombati S, Lou JK, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-lasting decrease in neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in a hippocampal neuronal culture model of spontaneous recurrent seizures. Brain Res. 1999;851:54–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein J, Farber D, Wasterlain C. Decreased calmodulin kinase activity after status epilepticus. Neurochem.Res. 1988;13:83–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00971859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein JM, Farber DB, Wasterlain CG. Regulation of type-II calmodulin kinase: functional implications. Brain Res.Brain Res.Rev. 1993;18:135–147. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90011-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein JM, Micevych P, Popper P, Huez G, Farber DB, Wasterlain CG. Long-lasting decreases of type II calmodulin kinase expression in kindled rat brains. Brain Res. 1992;584:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90903-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LS, Silva AJ, Abeliovich A, Watanabe Y, Tonegawa S, McNamara JO. Limbic epilepsy in transgenic mice carrying a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II alpha-subunit mutation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1995;92:6852–6855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DS, Haider SN, Blair RE, Deshpande LS, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Altered calcium/calmodulin kinase II activity changes calcium homeostasis that underlies epileptiform activity in hippocampal neurons in culture. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2006;319:1021–1031. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Calcium-mediated neurotoxicity: relationship to specific channel types and role in ischemic damage. Trends in neurosciences. 1988;11:465–469. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churn SB, Kochan LD, DeLorenzo RJ. Chronic inhibition of Ca(2+)/calmodulin kinase II activity in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy. Brain research. 2000a;875:66–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churn SB, Limbrick D, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Excitotoxic activation of the NMDA receptor results in inhibition of calcium/calmodulin kinase II activity in cultured hippocampal neurons. J.Neurosci. 1995;15:3200–3214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churn SB, Sombati S, Jakoi ER, Severt L, DeLorenzo RJ. Inhibition of calcium/calmodulin kinase II alpha subunit expression results in epileptiform activity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2000b;97:5604–5609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080071697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ. The calmodulin hypothesis of neurotransmission. Cell Calcium. 1981;2:365–385. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(81)90026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ. Calcium-calmodulin protein phosphorylation in neuronal transmission: a molecular approach to neuronal excitability and anticonvulsant drug action. Advances in Neurology. 1983;34:325–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Pal S, Sombati S. Prolonged activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-Ca2+ transduction pathway causes spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neurons in culture. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1998;95:14482–14487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:229–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol.Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erondu NE, Kennedy MB. Regional distribution of type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in rat brain. J.Neurosci. 1985;5:3270–3277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03270.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Greenberg ME. Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science. 1995;268:239–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7716515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenring JR, Vallano ML, Lasher RS, Ueda T, DeLorenzo RJ. Association of calmodulin-dependent kinase II and its substrate proteins with neuronal cytoskeleton. Prog.Brain Res. 1986;69:341–354. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61069-9. 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochan LD, Churn SB, Omojokun O, Rice A, DeLorenzo RJ. Status epilepticus results in an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activity in the rat. Neuroscience. 2000;95:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JE, Sheets D, Parsons JT, Rana A, Delorenzo RJ, Churn SB. A significant increase in both basal and maximal calcineurin activity in the rat pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. J.Neurochem. 2001;78:304–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Ban SS, Woo YJ, Kim SU. Calcium/calmodulin kinase II activity of hippocampus in kainate-induced epilepsy. Journal of Korean medical science. 2001;16:643–648. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbrick DD, Jr., Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Calcium influx constitutes the ionic basis for the maintenance of glutamate-induced extended neuronal depolarization associated with hippocampal neuronal death. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Bertram EH, Stringer JL. Functional anatomy of hippocampal seizures. Prog.Neurobiol. 1991;37:1–82. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90011-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlade-McCulloh E, Yamamoto H, Tan SE, Brickey DA, Soderling TR. Phosphorylation and regulation of glutamate receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature. 1993;362:640–642. doi: 10.1038/362640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KD, Gall CM, Benson DL, Jones EG, Isackson PJ. Decreased expression of the alpha subunit of Ca2+/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II mRNA in the adult rat CNS following recurrent limbic seizures. Brain Res.Mol.Brain Res. 1995;32:221–232. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00080-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Limbrick DD, Jr., Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ. Induction of spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges causes long-term changes in intracellular calcium homeostatic mechanisms. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:181–193. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Sombati S, Limbrick DD, Jr., DeLorenzo RJ. In vitro status epilepticus causes sustained elevation of intracellular calcium levels in hippocampal neurons. Brain research. 1999;851:20–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Sun D, Limbrick D, Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ. Epileptogenesis induces long-term alterations in intracellular calcium release and sequestration mechanisms in the hippocampal neuronal culture model of epilepsy. Cell Calcium. 2001;30:285–296. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Churn SB, DeLorenzo RJ. Ischemia-induced inhibition of calcium uptake into rat brain microsomes mediated by Mg2+/Ca2+ ATPase. J.Neurochem. 1997;68:1124–1134. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Churn SB, DeLorenzo RJ. Chronic inhibition of cortex microsomal Mg(2+)/Ca(2+) ATPase-mediated Ca(2+) uptake in the rat pilocarpine model following epileptogenesis. J.Neurochem. 2001;79:319–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Churn SB, Kochan LD, DeLorenzo RJ. Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus causes N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent inhibition of microsomal Mg(2+)/Ca(2+) ATPase-mediated Ca(2+) uptake. J.Neurochem. 2000;75:1209–1218. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin JB, Churn SB, Lothman EW, DeLorenzo RJ. Loss of type II calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase activity correlates with stages of development of electrographic seizures in status epilepticus in rat. Epilepsy Res. 1992;11:111–118. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(92)90045-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza M, Blair RE, Sombati S, Carter DS, Deshpande LS, DeLorenzo RJ. Evidence that injury-induced changes in hippocampal neuronal calcium dynamics during epileptogenesis cause acquired epilepsy. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2004;101:17522–17527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408155101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza M, Pal S, Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-term alteration of calcium homeostatic mechanisms in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 2001;903:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AC, DeLorenzo RJ. NMDA receptor activation during status epilepticus is required for the development of epilepsy. Brain Res. 1998;782:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara M, Alkon DL, DeLorenzo R, Goldenring JR, Neary JT, Heldman E. Modulation of calcium-mediated inactivation of ionic currents by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biophys.J. 1986;50:319–327. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields SM, Ingebritsen TS, Kelly PT. Identification of protein phosphatase 1 in synaptic junctions: dephosphorylation of endogenous calmodulin-dependent kinase II and synapse-enriched phosphoproteins. J.Neurosci. 1985;5:3414–3422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03414.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton MW, Holbert WH, 2nd, Lee AT, Bracey JM, Churn SB. Modulation of CaM kinase II activity is coincident with induction of status epilepticus in the rat pilocarpine model. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1389–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.19205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderling TR. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: role in learning and memory. Mol.Cell Biochem. 1993;127–128:93–101. doi: 10.1007/BF01076760. 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Recurrent spontaneous seizure activity in hippocampal neuronal networks in culture. J.Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1706–1711. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun DA, Sombati S, Blair RE, DeLorenzo RJ. Calcium-dependent epileptogenesis in an in vitro model of stroke-induced "epilepsy". Epilepsia. 2002;43:1296–1305. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.09702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun DA, Sombati S, Blair RE, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-lasting alterations in neuronal calcium homeostasis in an in vitro model of stroke-induced epilepsy. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata Y, Imoto K, Obata K. A mechanism for the inactivation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II during prolonged seizure activity and its consequence after the recovery from seizure activity in rats in vivo. Neuroscience. 2006;140:981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]