Abstract

The immunomodulatory ability of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) may be used to develop therapies for autoimmune diseases. Flk-1+ MSCs are a population of MSCs with defined phenotype and their safety has been evaluated in Phase 1 clinical trials. We designed this study to evaluate whether Flk-1+ MSCs conferred a therapeutic effect on collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), an animal model of rheumatic arthritis, and to explore the underlying mechanisms. Flk-1+ MSCs, 1–2 × 106, were injected into CIA mice on either day 0 or day 21. The clinical course of arthritis was monitored. Serum cytokine profile was determined by cytometric bead array kit or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Flk-1+ MSCs and splenocytes co-culture was conducted to explore the underlying mechanisms. Flk-1+ MSCs did not confer therapeutic benefits. Clinical symptom scores and histological evaluation suggested aggravation of arthritis in mice treated with MSCs at day 21. Serum cytokine profile analysis showed marked interleukin (IL)-6 secretion immediately after MSC administration. Results of in vitro culture of splenocytes confirmed that the addition of Flk-1+ MSCs promoted splenocyte proliferation and increased IL-6 and IL-17 secretion. Moreover, splenocyte proliferation was also enhanced in mice treated with MSCs at day 21. Accordingly, MSCs at low concentrations were found to promote lipopolysaccharide-primed splenocytes proliferation in an in vitro co-culture system. We propose that Flk-1+ MSCs aggravate arthritis in CIA model by at least up-regulating secretion of IL-6, which favours Th17 differentiation. When Flk-1+ MSCs are used for patients, we should be cautious about subjects with rheumatoid arthritis.

Keywords: IL-17, IL-6, immune regulation, mesenchymal stem cells, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multi-potential cells with extensive proliferative ability. They have been isolated from both bone marrow and other tissues, and are capable of differentiating into chondrocytes, osteocytes, adipocytes, endothelial cells and neural cells under appropriate cues [1,2]. The ability for isolation and expansion of MSCs in vitro without losing their phenotype or multi-lineage potential has granted MSCs a promising role in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [3,4].

Extensive evidence has shown that MSCs can exert profound immunosuppressive effects, as they can suppress T cell proliferation in culture and prolong skin graft across MHC barriers [5,6]. In addition to T cells, MSCs are also found to suppress proliferation of B cells [7], natural killer cells [8–10] and differentiation, proliferation and maturation of dendritic cells [11–16]. Consistently, MSCs have also been reported to be effective in reducing the incidence and severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplantation [17,18].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that is characterized by chronic inflammation of the joints. Previously, several independent groups have explored the therapeutic effects of MSCs in a collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model, and generated conflicting results [19–22]. Augello et al. reported that MSC treatment decreased the serum concentration of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and alleviated CIA by educating regulatory T cells (Tregs) [19], but Djouad et al. found that the addition of TNF-α to in vitro co-culture of MSCs and lymphocytes reversed the proliferation-suppressive properties of MSCs, and proposed that the presence of TNF-α in CIA animals led to aggravation of the disease after MSC treatment [20]. Indeed, there is some evidence showing that MSCs may up-regulate the immune response [23–25]. The underlying reasons for the discrepancy are currently unknown.

MSCs are heterogeneous cells without a defined phenotype and are always cultured using different modified methods by different laboratories. The difference in cells may account at least partly for the conflicting results in animal studies. Moreover, the circumstances in CIA animals are much more complicated than in vitro culture: the phenomena observed in cultured cells may not happen exactly as in animal models. To clarify this issue, it is important to investigate the therapeutic effect with a defined MSC population and explore the underlying mechanisms in vivo.

We have been engaged in the studies of Flk-1+ MSCs for a long time. They are a MSC subpopulation with a defined phenotype. We have completed Phase I clinical trials and have shown that Flk-1+ MSCs are safe and effective in the treatment of GVHD [26]; Phase II clinical trials for GVHD are on the way. In this study, we investigated the therapeutic effect of Flk-1+ MSCs on CIA mice. Considering the present application of Flk-1+ MSCs in clinical trials, this study is of great importance for the establishment of inclusion criteria in enrolling potential candidates.

Design and methods

Cell culture

Flk-1+ MSCs were isolated from bone marrow of dilute brown non-Agouti (DBA-1) mice and cultured as we have described previously [1,3]. Briefly, mononuclear cells were obtained by Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation from bone marrow flushes, depleted of haematopoietic cells, and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and Ham F12 medium (DF12) culture medium containing 40% MCDB-201 medium complete with trace elements (MCDB) medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor BB, insulin transferring selenium, linoleic acid and bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The non-adherent cell population was removed after 24–48 h and the adherent layer was cultured for approximately 1 week. When cells reached 90% confluence they were harvested by trypsinization (0·25% trypsin). All animal handling and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Flow cytometry

For immunophenotypic analysis, the Flk-1+ MSCs were detached and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0·5% BSA (Sigma) and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled primary antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. To detect intracellular antigens, we fixed cells in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4°C and then permeabilized them with 0·1% saponin (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. Same-species, same-isotype FITC-labelled or PE-labelled immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 were used as negative controls. Finally, cells were washed twice with PBS containing 0·5% BSA and resuspended in 0·5 ml PBS for fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Analysis was performed on a Beckman Coulter flow cytometer.

Induction of arthritis and MSC treatment

DBA-1 mice were obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) was produced in 8–10-week-old male DBA-1 mice, as described previously [20]. Briefly, bovine type II collagen (CII; Sigma) was emulsified with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant. Mice were injected at the base of the tail with 100 µl of emulsion containing 100 µg of collagen. On day 21, the mice received a booster injection of collagen emulsion in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. Flk-1+ MSCs (1–2 × 106 cells in 0·3 ml PBS) were infused intravenously on either day 0 (day 0 group) or day 21 (day 21 group).

Assessment of collagen-induced arthritis

Development of CIA was assessed twice a week. Paw swelling was assessed by measuring the thickness of the hind-paws using a caliper. For better comparison, we averaged the paw swelling increase on days 32, 35, 39, 43 and 49, respectively, which took into account most of the disease process. The symptom score was assessed using the following system, as reported previously [20]; briefly, grade 0: no swelling; grade 1: ≥ 0·1 mm increase in paw swelling; grade 2: ≥ 0·2 mm increase in paw swelling; grade 3: extensive swelling (≥ 0·3 mm increase in paw swelling) with severe joint deformity; and grade 4: pronounced swelling (≥ 0·45 mm increase in paw swelling) with pronounced joint deformity. On day 50, mice were anaesthetized for radiographic examination. The mice were then killed and limbs were fixed in 10% formalin, sections were prepared, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological assessment.

Splenocyte proliferation assay

Splenocytes were isolated by mechanical dissociation, followed by red blood cell lysis [10 min in NH4Cl (8·4 g/l)/potassium hydrogen carbonate (KHCO3) (1 g/l) buffer at 4°C]. Responder splenocytes were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, incubated with 5 µg/ml concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma) for T cell stimulation or 25 µg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma) for B cell stimulation. MSCs (10 Gy irradiated) were added to the splenocytes at ratios of 1:10 or 1:100. After 3 days' incubation, cells were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine (1 µCi/well) for the last 18 h, harvested and counted using a Topcount NXT (Canberra Packard, Meriden, CT, USA). Results were expressed in counts per minute (cpm) and presented as means ± standard deviation (s.d.) obtained from triplicate cultures.

Similarly, splenocytes were co-cultured in 24-well plates with or without Flk-1+ MSCs. One week later, supernatants were harvested and cytokine concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits as described below.

Serum cytokine profile of CIA animals

Serum samples were obtained from the angular vein of mice on days 7, 20, 28, 35, 42 and 49, respectively, and serum concentrations of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, interferon (IFN)-γ and TNF-α were determined using the Murine Cytometric Bead Array Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serum concentrations of other cytokines and IgG were determined by ELISA kits after the animals were killed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were conducted using the one-tailed Student's t-test. P-values of less than 0·05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Immunophenotype and immunosuppressive property of Flk-1+ MSCs

Flk-1+ MSCs were obtained by culturing bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells under culture conditions as described in Material and methods. Flow cytometry phenotype analysis showed that these cells were positive for Flk-1, CD29, CD44, CD105 and major histocompatibility complex 1 (MHC-1), but negative for CD31, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD108, CD117 and MHC-2 (Fig. 1a and b). Thus they were termed Flk-1+ MSCs. We examined the immunomodulatory properties of Flk-1+ MSCs in an in vitro tritiated thymidine ([3H]-TdR) incorporation assay. We found that Flk-1+ MSCs suppressed the proliferation of both T (ConA-primed) and B (LPS-primed) lymphocytes (P < 0·01, Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Immunophenotype and immunosuppressive properties of Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Cells were cultured from murine bone marrow. (a) Immunophenotype was detected by flow cytometry. MSCs were positive for CD29, CD44, CD105 and major histocompatibility complex 1 (MHC-1) and negative for CD31, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD108, CD117 and MHC-2. (b) Cells were positive for intracellular antigen Flk-1. (c) Murine splenocytes were stimulated with either concanavalin A (ConA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Cell proliferation was shown by tritiated thymidine ([3H]-TdR) incorporation and expressed in counts per minute (cpm). Addition of irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs (MSC : splenocyte = 1:10) suppressed stimulated splenocyte proliferation. (***P < 0·01).

Flk-1+ MSCs treatment at different time-points have different effects on CIA mice

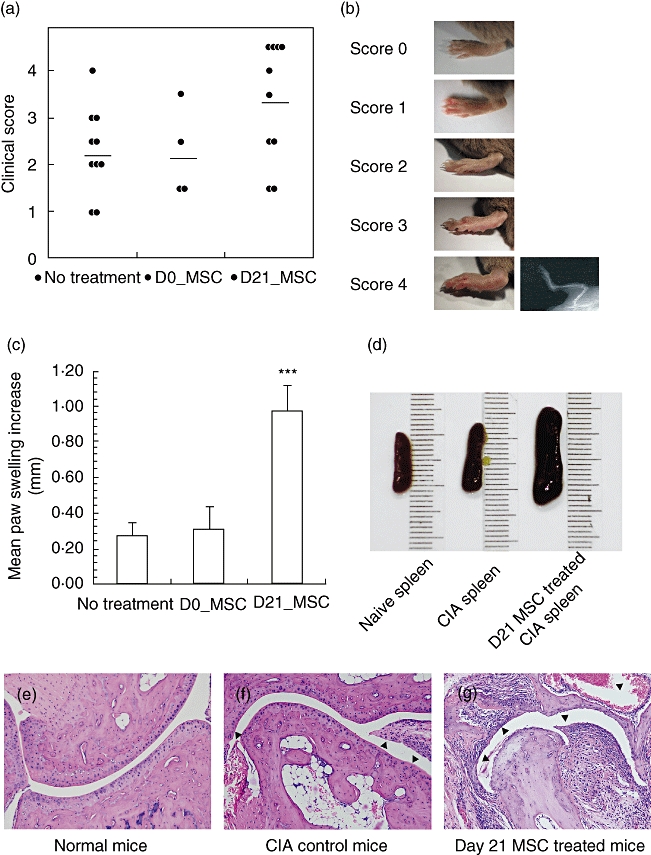

Male DBA/1 mice bearing the MHC H-2q haplotype (8–10 weeks old) were immunized with CII emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant on day 0 and again with CII emulsified in Freund's incomplete adjuvant on day 21 to induce CIA. The hind-paws of immunized mice began to swell, and maximum swelling developed from days 32 to 49. Flk-1+ MSCs (1–2 × 106 cells/mouse) were infused intravenously on either days 0 or 21. The mean hind-paw swelling from days 32 to 49 was 0·27 ± 0·07 mm, 0·31 ± 0·13 mm and 0·97 ± 0·15 mm in the control group, day 0 group and day 21 group, respectively (Fig. 2c). The mean hind-paw swelling in the day 21 group was significantly greater than that in control group (P < 0·01). According to the criteria of symptom score defined in Material and methods, hind-paws in the day 21 group had a mean symptom score of 3·35, while the mean symptom scores in the day 0 group and control group were 2·25 and 2·3, respectively (Fig. 2a). Treatment with Flk-1+ MSC at day 21 aggravated symptoms of CIA mice dramatically. When all mice were killed after 50 days, we noted that the spleens of mice in the day 21 group were obviously larger than those of both the control group and naive DBA-1 mice (Fig. 2d). We compared the proliferation capacity of splenocytes in the different groups, and found that the splenocytes of the day 21 group proliferated more vigorously than those of control mice (P < 0·05, Fig. 5d). Histological examination confirmed aggravation of disease in the day 21 group (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Aggravation of collagen-induced arthritis after Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) treatment at day 21. (a) Clinical scores of each group of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice were evaluated according to standards described in Material and methods. (D0_MSC = day 0 group; D21_MSC = day 21 group). (b) Paws with different clinical scores. Paws of score 4 were confirmed by radiographic examination showing limb deformities and/or bone erosion. (c) Mean paw swelling increase was calculated by averaging the paw swelling increases on days 32, 35, 39, 43 and 49 (***P < 0·01 versus control group). (d) Spleens recovered from naive mice, mice in the control group and the day 21 group. (e–g) Histological sections of naive mice, CIA control mice or mice in the day 21 group were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Fig. 5.

Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) at low concentrations stimulate B cell proliferation in vitro. (a) Splenocytes from naive mice were cultured with irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs at different doses of Flk-1+ MSCs. Cell proliferation was measured by tritiated thymidine ([3H]-TdR) incorporation and expressed in counts per minute (cpm). (b) Concanavalin A (ConA)-stimulated splenocytes from naive mice were cultured with irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs at different doses. (c) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated splenocytes from naive mice were cultured with irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs at different doses. (d) Proliferation of cell from mice of the control group and the day 21 group was shown by [3H]-TdR incorporation. (e) ConA-stimulated splenocytes from collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice were cultured with irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs at different doses. (f) LPS-stimulated splenocytes from CIA mice were cultured with irradiated Flk-1+ MSCs at different doses (*P < 0·05 versus culture without Flk-1+ MSCs or control CIA mice; ***P < 0·01 versus culture without Flk-1+ MSCs or control CIA mice).

Infusion of MSCs at day 21 markedly promotes IL-6 secretion of CIA mice

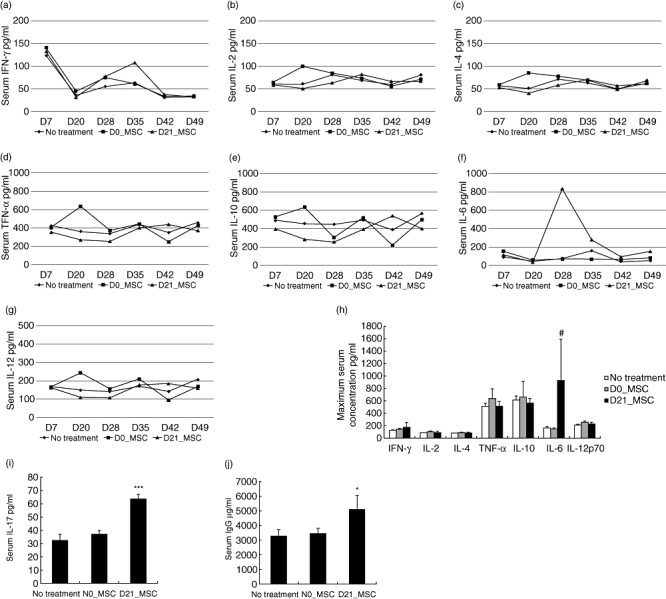

To determine the underlying mechanism by which Flk-1+ MSCs infused at day 21 aggravated arthritis in CIA mice, we investigated the serum cytokine profiles of CIA mice in each group. Blood samples were obtained on days 7, 14, 20, 28, 35, 43 and 49, respectively. Taking advantage of a cytometric bead array (CBA) flex set kit (BD Pharmingen), we were able to examine simultaneously the serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α without killing the mice. We documented soaring serum IL-6 in the day 21 group from 30 pg/ml on days 20–834 pg/ml on day 28 (Fig. 3f). By contrast, serum IL-6 in untreated CIA mice reached the highest level (157 pg/ml) only at day 35. The serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α in the day 21 group moved smoothly from days 20 to 28, and were similar to those in the control group (Fig. 3a–e and g). Thus the maximum serum IL-6 concentration of the day 21 group was 4·64-fold higher than that of control group (927 pg/ml versus 164 pg/ml; P < 0·1; Fig. 3h). Therefore, Flk-1+ MSC treatment at day 21 had resulted in a dramatic increase of serum IL-6. On the other hand, the maximum serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α in the day 21 group were similar to those in the untreated group (P = 0·20–0·49; Fig. 3h). Moreover, serum IL-17 and IgG were examined by ELISA. The results showed that both serum IL-17 (P < 0·01; Fig. 3i) and IgG (P < 0·05; Fig. 3j) were increased in the day 21 group.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of serum cytokine concentrations between the day 21 group, the day 0 group and control mice. (a–g) Serum samples were obtained on days 7, 20, 28, 35, 42 and 49, respectively. Serum concentrations of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α were determined using the Murine Cytometric Bead Array Kit (BD). (h) Maximum serum cytokine concentrations during the disease progress of an individual mouse. Mice in the day 21 group showed 4·46-fold increase in serum IL-6 versus untreated collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice. (i–j) Serum concentrations of IL-17 and immunoglobulin (Ig)G (#P < 0·1 versus control mice; *P < 0·05 versus control mice; ***P < 0·01 versus control mice).

Co-culture of Flk-1+ MSCs and LPS-primed splenocytes leads to a threefold increase in supernatant IL-6 concentration

To elucidate the relation between Flk-1+ MSC infusion and increase of IL-6, we co-cultured Flk-1+ MSCs with LPS-primed splenocytes. We found that the IL-6 level in the supernatant increased 3·7-fold in the presence of Flk-1+ MSCs (P < 0·01, Fig. 4a). We used splenocytes from CIA mice to repeat the experiment and found similar results (threefold increase, P < 0·05; Fig. 4b). We also found that the IL-17 supernatant was increased by MSC co-culture (P < 0·01; Fig. 4c and d).

Fig. 4.

Addition of Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to splenocyte cultures increase supernatant concentrations of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-17. (a,c) Splenocytes from naive mice stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were cultured with or without Flk-1+ MSCs (MSC : splenocyte = 1:10). (b,d) Splenocytes from collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice stimulated by LPS were cultured with or without Flk-1+ MSCs. Supernatant concentrations of IL-6 and IL-17 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (*P < 0·05 versus culture without Flk-1+ MSCs; ***P < 0·01 versus culture without Flk-1+ MSCs).

Reversal of immunomodulatory effects of Flk-1+ MSCs on B cells at low MSC concentrations

Enhanced splenocyte proliferation observed in the day 21 group (Fig. 5d, P < 0·05) conflicted with the observation that Flk-1+ MSCs suppressed activated T and B lymphocytes in vitro (Fig. 1c). We thus investigated whether the immunomodulatory properties of Flk-1+ MSC were dependent on the ratio of MSCs to splenocytes. As expected, we found that a high dose of Flk-1+ MSCs (MSC : splenocyte = 1:10) suppressed spontaneous splenocyte proliferation of the mice, while a low dose of Flk-1+ MSCs (MSC : splenocyte = 1:100) enhanced proliferation (Fig. 5a, P < 0·05). We found further that Flk-1+ MSCs suppressed ConA-primed T cell proliferation at both high and low concentrations (Fig. 5b, P < 0·01). However, Flk-1+ MSCs suppressed LPS-primed B cell proliferation only at high concentrations. The suppressive properties of Flk-1+ MSCs on LPS primed B cells disappeared at low concentrations (Fig. 5c, P < 0·01). We then repeated these experiments with splenocytes of CIA mice and obtained similar results (Fig. 5e and f).

Discussion

Previously, several independent researchers have investigated the possibility of treating CIA with MSCs and generated conflicting results. First, Djouad et al. found C3 MSC treatment did not confer any benefit to CIA and aggravation of the disease was observed in day 21 MSC-treated mice. Djouad et al. attributed the reversal of immunosuppressive properties of MSCs to the presence to TNF-α, as the addition of TNF-α in in vitro culture reversed the suppressive effect of MSC on T cell proliferation [20]. Later, Augello et al. reported that allogenic MSC injection prevented the occurrence of severe, irreversible damage to bone and cartilage with decreased serum TNF-α concentrations through induction of antigen-specific Tregs[19].

MSC is a heterogeneous population with a number of subpopulations, which are possibly different from each other. It has been demonstrated that those slight differences in MSCs, together with various in vivo situations, will lead to opposing outcomes – either immunosuppressive or immunogenic [24,25,27,28]. Djouad et al. used a murine MSC line, C3H10T1/2, and Augello et al. used primary MSC culture in 10% FBS [19,20]. The Flk-1+ MSCs we used in this study were cultured in 2% FBS medium with a defined phenotype. It is highly possible that those differences in different MSC subpopulations led to opposing outcomes in CIA. To clarify this conflicting evidence it is necessary, first, to define precisely the cells used in the experiment. With regard to the underlying mechanism of aggravation of arthritis, Djouad et al. have proposed that the presence of TNF-α accounts for aggravation of the disease after MSC treatment. However, the authors did not provide in vivo evidence showing that this happened in their animal model. TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine present in a number of autoimmune diseases. Augello et al. showed that MSC treatment reduced serum TNF-α and lessened CIA [19]. We have also found that Flk-1+ MSCs could reduce serum TNF-α and alleviate trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS)-induced colonitis (data not shown). Thus we believe that the presence of TNF-α is not the primary factor that counteracts the immunosuppressive effects of Flk-1+ MSCs.

CIA is induced in genetically susceptible strains of mice by immunization with type II collagen (CII) to imitate human rheumatic arthritis, and both T cell and B cell responses to CII in the model are required to establish pathogenesis [29]. First, CIA was classified as a T helper type 1 (Th1)-mediated disease [30–32]. However, conflicting evidence shows that anti-IFN-γ-treated mice and IFN-γ- or IFN receptor-deficient mice indeed develop CIA [33,34], rendering that hypothesis highly unconvincing. More recent studies have updated our knowledge of the pathogenesis of CIA, and demonstrated that CIA was mediated by an IL-17-producer CD4+ T cell subpopulation, termed Th17, which was distinct from Th1 and Th2 [35]. Mice lacking IL-23 (p19−/−) have been shown to be resistant to CIA, which was correlated with an absence of IL-17-producing Th17 cells despite normal induction of collagen-specific, IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells. On the contrary, knock-out mice for the Th1 cytokine IL-12 (p35−/−) have more IL-17-producing Th17 cells and develop CIA readily [36]. The key role of Th17 in CIA was confirmed further by reports showing that CIA was suppressed in IL-17-deficient mice and that administration of neutralizing anti-IL-17 antibodies reduced significantly the severity of CIA [37,38].

IL-6 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β are two important factors that may be involved in the aggregation of arthritis observed in our experiment. TGF-β1 can increase the IL-17+ cell fraction markedly, and is sufficient by itself to promote robust Th17 development [39–41]. Meanwhile, TGF-β1 also induces the expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) (Treg), a suppressive T cell subpopulation [42]. IL-6 can inhibit TGF-β-induced generation of FoxP3+ Treg cells and help to establish Th17 prominence [43,44]. Moreover, anti-IL-6R treatment for CIA has been confirmed to suppress the differentiation of antigen-specific Th17 and the onset of the disease [45]. In this study, we have shown in vivo that administration of Flk-1+ MSCs at day 21 increased the serum level of IL-6 (day 25) strikingly. This was confirmed in in vitro co-culture experiments. The increased IL-6 would then favour Th17 differentiation and contribute to aggravation of the disease, as discussed above.

Although T cells play a prominent role in the regulation and development of the autoimmune response in CIA, B cells and autoantibodies to murine CII appear to be the primary mechanism of immunopathogenesis in this model. It has been demonstrated previously that passive transfer of CII-specific T cells cannot induce arthritis [46,47], yet the passive transfer of immune sera from arthritic mice to naive mice induces severe inflammation [48–55], and once the transferred antibody is depleted, inflammatory responses subside. The autoantibody activates complement cascades and the inflammation that follows contributes to the development of erosive arthritis [53]. Reports from independent laboratories have demonstrated that MSCs can prolong the survival of plasma cells and stimulate antibody secretion through IL-6 and very late activation antigen-4 (VLA-4) [56,57]. IL-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) signalling has also been reported to regulate the ability of naive T cells to acquire B cell help capacity [58].

In this study, we found that the splenocytes of Flk-1+ MSC-treated mice showed a higher proliferative capacity than those of the control CIA mice. In vitro co-culture experiments revealed that Flk-1+ MSCs suppressed B cell proliferation at high concentrations but, interestingly, promoted B cell proliferation at low concentrations. The dose of MSC administered to the mice was approximately 1–2 × 106 Flk-1+ MSCs per mouse; compared to 108 or more splenocytes in each mouse, the stimulatory effect of Flk-1+ MSCs might play a dominant role on B cells in CIA animals. Consistently, MSC-treated mice showed a mild increase in serum IgG compared to untreated CIA mice. Alternatively, the enhancement of splenocyte proliferation and IgG secretion in Flk-1+ MSC-treated mice might be caused by the specific in vivo environment of CIA, rather than a dose-dependent effect of Flk-1+ MSCs observed in in vitro culture. It is known that in vitro suppression in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) does not always correlate with in vivo immune modulation. To address this question, we should increase the dose given to mice and examine the dose-dependency in vivo. However, we failed to increase the dose of MSC infusion to 1–2 × 107 because of pulmonary embolism and the subsequent death of the animals. The mechanism of the differential regulation of B cell proliferation by MSC in vitro is still unknown. Rasmusson et al. have reported previously that similar differential regulation of human B cells by MSCs might be associated with the intensity of stimulation [23]. The dose effect of MSC and the dose effect of stimulation might share some common mechanisms.

IL-6 is a cytokine that enhances B cell function. The co-existence of increased production of IL-6 (Fig. 4) and decreased proliferation of B cells (Fig. 5), while MSCs were co-cultured with splenocytes at ratio of 1:10, indicates that two independent pathways co-exist – one promotes B cells, and the other suppresses B cells. The subtle balance between them may explain the differential regulation of B cell proliferation by MSCs in our and other studies [23].

Flk-1+ MSCs exacerbated CIA only in the day 21 infusion group and not in the day 0 group. The difference in the in vivo physiological environment of the animal between days 0 and 21 might account for this issue. The onset of arthritis begins after the second injection of CII on day 21. Therefore, the physiological condition of the animal on day 21 is closer to that of the animal suffering from arthritis, while the physiological condition of the animal on day 0 is closer to that of the healthy animals. The results of day 0 mice indicated that Flk-1+ MSCs did not have a preventive effect on CIA, and the results of day 21 showed the aggravation risks of treating CIA with Flk-1+ MSCs.

In conclusion, we propose that elevated IL-6, by enhancing Th17 and plasma cells, is responsible for the aggravation of CIA after day 21 Flk-1+ MSC treatment (Fig. 6). In Phase II clinical trials of Flk-1+ MSCs, special attention should be paid to patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Fig. 6.

Illustration of the proposed mechanism of aggravation of arthritis by Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) treatment at day 21. Surfing interleukin (IL)-6, by enhancing T helper type 17 (Th17) and plasma cells, and the stimulatory effects of a low dose of Flk-1+ MSCs on B cell proliferation account primarily for the aggravation of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) after Flk-1+ MSC treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the ‘863 Projects’ of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (no. 2006AA02A109. 2006AA02A115); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30570771); the Beijing Ministry of Science and Technology (no. D07050701350701) and the Cheung Kong Scholars programme.

Disclosure

All disclosures were provided in the ‘Acknowledgements’ section.

References

- 1.Fang B, Liao L, Shi M, Yang S, Zhao RC. Multipotency of Flk1CD34 progenitors derived from human fetal bone marrow. J Lab Clin Med. 2004;143:230–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao Y, Sun Z, Liao L, Meng Y, Han Q, Zhao RC. Human adipose tissue-derived stem cells differentiate into endothelial cells in vitro and improve postnatal neovascularization in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:370–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng W, Han Q, Liao L, et al. Engrafted bone marrow-derived flk-(1+) mesenchymal stem cells regenerate skin tissue. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:110–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Yan X, Sun Z, et al. Flk-1+ adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into skeletal muscle satellite cells and ameliorate muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:695–706. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartholomew A, Patil S, Mackay A, et al. Baboon mesenchymal stem cells can be genetically modified to secrete human erythropoietin in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1527–41. doi: 10.1089/10430340152480258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng W, Han Q, Liao L, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow-derived flk-1+Sca-1- mesenchymal stem cells leads to stable mixed chimerism and donor-specific tolerance. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:861–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107:367–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111:1327–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107:1484–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Ge W, Li C, et al. Effects of mesenchymal stem cells on differentiation, maturation, and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:263–71. doi: 10.1089/154732804323099190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Zhang W, Yue H, et al. Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on the differentiation of dendritic cells from CD34+ cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:719–31. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood. 2005;105:2214–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramasamy R, Fazekasova H, Lam EW, Soeiro I, Lombardi G, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007;83:71–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244572.24780.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Liu B, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005;105:4120–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang B, Song YP, Liao LM, Han Q, Zhao RC. Treatment of severe therapy-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease with human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:389–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringden O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2006;81:1390–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Cancedda R, Pennesi G. Cell therapy using allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents tissue damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1175–86. doi: 10.1002/art.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djouad F, Fritz V, Apparailly F, et al. Reversal of the immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells by tumor necrosis factor alpha in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1595–603. doi: 10.1002/art.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng ZH, Li XY, Ding J, Jia JF, Zhu P. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell and mesenchymal stem cell-differentiated chondrocyte suppress the responses of type II collagen-reactive T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxf) 2008;47:22–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi JJ, Yoo SA, Park SJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing interleukin-10 attenuate collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmusson I, Le Blanc K, Sundberg B, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells stimulate antibody secretion in human B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:336–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauta AJ, Westerhuis G, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink EG, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells are immunogenic in an allogeneic host and stimulate donor graft rejection in a nonmyeloablative setting. Blood. 2006;108:2114–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudres M, Norol F, Trenado A, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:7761–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Sun Z, Chen B, et al. Ex vivo expansion and in vivo infusion of bone marrow-derived Flk-1+CD31-CD34- mesenchymal stem cells: feasibility and safety from monkey to human. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:349–57. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aksu AE, Horibe E, Sacks J, et al. Co-infusion of donor bone marrow with host mesenchymal stem cells treats GVHD and promotes vascularized skin allograft survival in rats. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itakura S, Asari S, Rawson J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells facilitate the induction of mixed hematopoietic chimerism and islet allograft tolerance without GVHD in the rat. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:336–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brand DD, Kang AH, Rosloniec EF. Immunopathogenesis of collagen arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2003;25:3–18. doi: 10.1007/s00281-003-0127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mauri C, Williams RO, Walmsley M, Feldmann M. Relationship between Th1/Th2 cytokine patterns and the arthritogenic response in collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1511–18. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boissier MC, Chiocchia G, Bessis N, et al. Biphasic effect of interferon-gamma in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1184–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauritz NJ, Holmdahl R, Jonsson R, Van der Meide PH, Scheynius A, Klareskog L. Treatment with gamma-interferon triggers the onset of collagen arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1297–304. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manoury-Schwartz B, Chiocchia G, Bessis N, et al. High susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis in mice lacking IFN-gamma receptors. J Immunol. 1997;158:5501–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vermeire K, Heremans H, Vandeputte M, Huang S, Billiau A, Matthys P. Accelerated collagen-induced arthritis in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Vargas-Rojas MI, Cabral AR. Autoimmune inflammation from the Th17 perspective. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy CA, Langrish CL, Chen Y, et al. Divergent pro- and antiinflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1951–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lubberts E, van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, et al. IL-17 promotes bone erosion in murine collagen-induced arthritis through loss of the receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin balance. J Immunol. 2003;170:2655–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li MO, Wan YY, Flavell RA. T cell-produced transforming growth factor-beta1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1- and Th17-cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;26:579–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korn T, Mitsdoerffer M, Croxford AL, et al. IL-6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18460–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujimoto M, Serada S, Naka T. [Role of IL-6 in the development and pathogenesis of CIA and EAE] Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2008;31:78–84. doi: 10.2177/jsci.31.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trentham DE, Dynesius RA, David JR. Passive transfer by cells of type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:359–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI109136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmdahl R, Klareskog L, Rubin K, Larsson E, Wigzell H. T lymphocytes in collagen II-induced arthritis in mice. Characterization of arthritogenic collagen II-specific T-cell lines and clones. Scand J Immunol. 1985;22:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1985.tb01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Englert ME, Ferguson KM, Suarez CR, Oronsky AL, Kerwar SS. Passive transfer of collagen arthritis: heterogeneity of anti-collagen IgG. Cell Immunol. 1986;101:373–9. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hietala MA, Jonsson IM, Tarkowski A, Kleinau S, Pekna M. Complement deficiency ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:454–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loutis N, Bruckner P, Pataki A. Induction of erosive arthritis in mice after passive transfer of anti-type II collagen antibodies. Agents Actions. 1988;25:352–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01965042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart JM, Cremer MA, Townes AS, Kang AH. Type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Passive transfer with serum and evidence that IgG anticollagen antibodies can cause arthritis. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stuart JM, Dixon FJ. Serum transfer of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Exp Med. 1983;158:378–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson WC, Brown PS, Pitcock JA, Townes AS. Passive transfer studies with type II collagen antibody in B10.D2/old and new line and C57Bl/6 normal and beige (Chediak–Higashi) strains: evidence of important roles for C5 and multiple inflammatory cell types in the development of erosive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:460–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wooley PH, Luthra HS, Singh SK, Huse AR, Stuart JM, David CS. Passive transfer of arthritis to mice by injection of human anti-type II collagen antibody. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:737–43. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wooley PH, Luthra HS, Krco CJ, Stuart JM, David CS. Type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice. II. Passive transfer and suppression by intravenous injection of anti-type II collagen antibody or free native type II collagen. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:1010–17. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Minges Wols HA, Underhill GH, Kansas GS, Witte PL. The role of bone marrow-derived stromal cells in the maintenance of plasma cell longevity. J Immunol. 2002;169:4213–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carrasco YR, Batista FD. B-cell activation by membrane-bound antigens is facilitated by the interaction of VLA-4 with VCAM-1. EMBO J. 2006;25:889–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eddahri F, Denanglaire S, Bureau F, et al. Interleukin-6/STAT3 signalling regulates the ability of naive T cells to acquire B cell help capacities. Blood. 2009;113:2426–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]