Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a serious public health problem, especially in developing countries, where available vaccines are not part of the vaccination calendar. We evaluated different respiratory mucosa immunization protocols that included the nasal administration of Lactococcus lactis-pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) live, inactivated, and in association with a probiotic (Lc) to young mice. The animals that received Lc by the oral and nasal route presented the highest levels of immunoglobulin (Ig)A and IgG anti-PppA antibodies in bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) and IgG in serum, which no doubt contributed to the protection against infection. However, only the groups that received the live and inactivated vaccine associated with the oral administration of the probiotic were able to prevent lung colonization by S. pneumoniae serotypes 3 and 14 in a respiratory infection model. This would be related to a preferential stimulation of the T helper type 1 (Th1) cells at local and systemic levels and with a moderate Th2 and Th17 response, shown by the cytokine profile induced in BAL and by the results of the IgG1/IgG2a ratio at local and systemic levels. Nasal immunization with the inactivated recombinant strain associated with oral Lc administration was able to stimulate the specific cellular and humoral immune response and afford protection against the challenge with the two S. pneumoniae serotypes. The results obtained show the probiotic-inactivated vaccine association as a valuable alternative for application to human health, especially in at-risk populations, and are the first report of a safe and effective immunization strategy using an inactivated recombinant strain.

Keywords: inactivated mucosal vaccine, pneumococcal infection, probiotic, recombinant lactic acid bacteria

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important respiratory pathogen with high incidence in both developed and developing countries. Pneumococcal disease implies a significant economic burden to health care systems in Latin America [1]. Defence against pneumococcal infection involves innate and adaptive immune responses, and the control of these infections involves protective adaptive immunity through vaccine administration. However, pneumococcal vaccines available at present do not constitute a definitive solution to this important health problem. This is because, while pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPV) have the potential to prevent disease and death, the degree of protection that they offer against different serotypes and within different populations is uncertain. In addition, while the new conjugate vaccines have shown effectiveness in young children, they do not represent a definitive solution. Protecting against those vaccine strains would give other pneumococcal strains the opportunity to cause infection and the impact of a pneumococcal vaccination programme would be reduced if serotype replacement were significant [2,3]. Moreover, the high cost of conjugate vaccines is one of the main reasons for the search for better immunization strategies against S. pneumoniae. New strategies in the fight against this pathogen involve the identification of pneumococcal proteins and, globally, scientific efforts continue to look for conserved proteins. Some pneumococcal surface proteins are serotype-independent and represent a promising alternative for the design of a vaccine [4–6]. Adjuvants are necessary for protein administration by the mucosal route and cholera toxin or heat-labile enterotoxin has been used. However, the combination of proteins with these kinds of co-adjuvants may not be clinically safe [7]; this is the reason why new vaccines that are safe and inexpensive for global application to populations at risk are necessary, especially in developing countries. In this sense, probiotic microorganisms emerge as a valuable alternative, as they have important immunomodulatory effects and multiple applications that include the prevention of allergies [8,9] and infectious diseases [10,11], anti-carcinogenic activity [12] and the improvement of intestinal bowel disease symptoms [13], among other beneficial effects on the health of humans and animals. In addition, the generally regarded as safe (GRAS) condition of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), together with their effects on the immune system of the host, make them good candidates for their use as antigen vehicles. In previous work we have demonstrated that non-recombinant Lactoccocus lactis administered orally and nasally has intrinsic adjuvant properties and stimulates both innate and specific immunity [14,15]. It also improves protection against a respiratory infection with S. pneumoniae. On the basis of these results, and in order to potentiate the protective effect of L. lactis, we designed a recombinant L. lactis able to express pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) on its surface: L. lactis-PppA+[16]. Pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) is a small protein conserved antigenically among different serotype strains of S. pneumoniae (3, 5, 9, 14, 19 and 23). It has been reported that nasal immunization of adult mice with PppA administered with mucosal adjuvants elicits antibodies that are effective in reducing pneumococcal nasal colonization [17]. The recombinant strain L. lactis-PppA+ administered nasally showed effectiveness in the induction of protective antibodies against systemic and respiratory pneumoccocal infection in both young and adult mice [16]. The results obtained with recombinant bacteria that express different pneumococcal antigens constitute an important advance in the fight against the pathogen. However, the potential application of a live recombinant strain by the nasal route in humans still presents aspects that need to be resolved, such as the elimination of the antibiotic resistance genes used in its selection. Hanniffy et al. evaluated the induction of protective antibodies by a dead recombinant lactococcus in a pneumococal infection model [18]. This recombinant strain expresses as an antigen a protein different from the one used by our work team, and the results demonstrated that protection with the live bacterium was better than that obtained with the dead recombinant bacterium [18]. These results cannot be extrapolated to other recombinant bacteria, in which the variable is not only the antigen expressed, but also the mouse strain and the model used for the study of the effectiveness of the vaccine. The evaluation of new conserved antigens and innovative strategies for the immunization of the respiratory mucosa continue to pose a challenge to the global scientific community. The induced immune response is extremely important in the selection of the correct vaccine. Thus, T helper (Th) CD4+ cells play a key role in the adaptive immune response by co-operating with B cells for the production of antibodies through direct contact or through the release of cytokines that regulate the Th type 1 (Th1)/Th2 balance. On the other hand, lactobacilli enhanced the antigen-specific immune response induced by viral or bacterial vaccines [19–21]. However, not all Lactobacillus strains have intrinsic adjuvanticity or can be used as mucosal adjuvants [22,23]. The ability of probiotics to modulate the immune response depends in great part upon the cytokine profile induced, which varies considerably with the strain and dose used [24,25]. Previous studies in our laboratory with pneumococcal infection models in immunocompetent [26] and immunocompromised [27] mice showed that oral administration of the probiotic L. casei CRL 431 improved the immune response of the host against respiratory pathogens and that its effect was dose-dependent [26–29]. On the basis of the above, we considered that it would be possible to improve the immunity induced by the recombinant strains by combining their application with a probiotic strain. There are very few comparative studies of the lung mucosal and systemic immune response induced by a live and an inactivated recombinant bacterium, and we think that none of them has dealt with the study of the co-administration of a probiotic strain and a recombinant vaccine. Thus, the aim of this work is to evaluate the adaptive immune response induced by L. lactis-PppA live and inactivated and in association with the oral and nasal administration of a probiotic strain and to analyse the possible mechanism involved in the protection against a pneumococcal infection.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

Recombinant Lactococcus lactis-PppA (LL) was obtained in our laboratory and the development of this strain was described in a previous report from our work group [16]. L. lactis-PppA was grown in M17-glu plus erythromycin (5 µg/ml) at 30°C until cells reached an optical density (OD)590 of 0·6 and then induced with 50 ng/ml of nisin for 2 h. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min, then washed three times with sterile 0·01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·2, and finally resuspended in PBS at the appropriate concentrations to be administered to mice. For inactivation, bacterial suspensions were pretreated with mitomycin C [30]. The inactivated strain was called dead-L. lactis-PppA: D-LL L. casei CRL 431 (Lc) [25–27], obtained from the Centro de Referencias para Lactobacilos (CERELA) culture collection, was cultured for 8 h at 37°C (final log phase) in Man–Rogosa–Sharpe broth (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK), harvested and washed with sterile 0·01 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7·2. The bacterial suspension was adjusted to the desired concentration (109 cell/day/mouse) for later administration through the oral and nasal routes.

Two different serotypes of S. pneumoniae, kindly provided by Dr M. Regueira from the Laboratory of Clinical Bacteriology, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Argentina, were used. Freshly grown colonies of S. pneumoniae strains, serotypes 3 and 14, were suspended in Todd Hewitt broth (THB) and incubated at 37°C until the log phase was reached [16]. Then, the cell concentration of the pathogen was adjusted to the dose used in the challenge assays (106 cells/mouse).

Immunization procedures

Three-week-old (young) Swiss albino mice were obtained from the closed colony at CERELA. Animals were housed in plastic cages and environmental conditions were kept constant, in agreement with the standards for animal housing. Each parameter studied was carried out in five to six mice for each time-point. The Ethical Committee for Animal Care at CERELA approved experimental protocols.

Mice were immunized nasally with recombinant L. lactis PppA (LL), induced previously with nisin, at a dose of 108 cells/day/mouse, on days 0, 14 and 28, following an immunization protocol assessed previously by our team [16]. The inoculum was instilled slowly into the nostril of each mouse in a 25 µl volume. The inactivated bacterium (D-LL) was administered at the same concentration and using a procedure similar to that used for LL. The administration of the probiotic strain was carried out during the 2 days prior to each immunization with LL or D-LL. The animals treated orally with the probiotic received 109 cell/day/mouse of L. casei (Lc) in the drinking water. This dose was selected on the basis of our previous studies, in which we demonstrated that Lc induced a significant increase in the innate and acquired immune defence mechanisms of the host in a pneumococcal infection model in adult mice [26]. Nasal administration of the probiotic strains was carried out at the same concentration as oral administration (109 cells/day/mouse) in a final volume of 25 µl and associated only with D-LL. The administration of L. casei in association with the live vaccine through the nasal route was not carried out, because we considered that the application of two live bacteria by this route would imply too high a microbial load in the upper airways. In addition, even if it was beneficial in our model, it would not be of practical or safe application for transference to humans, which is the aim of our research. Young non-immunized mice that received PBS were used as control.

Serum and bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) were collected for determination of specific antibodies (days 0, 14, 28 and 42). In addition, BAL samples were collected on days 0, 28 and 42 for cytokine detection. BAL samples were obtained according to the technique described previously [26]. Briefly, the trachea was exposed and intubated with a catheter and two sequential bronchoalveolar lavages were performed in each mouse by injecting 0·5 ml of sterile PBS. The BAL samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 900 g and the supernatant fluid was frozen at −70°C for subsequent analyses.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for anti-PppA antibodies

Serum and BAL antibodies against PppA protein were determined by ELISA modified from Green et al.[17]. Briefly, plates were coated with rPppA (100 µl of a 5 µg/ml stock in sodium carbonate–bicarbonate buffer, pH 9·6, per well). Non-specific protein binding sites were blocked with PBS containing 5% non-fat milk. Samples were diluted (serum 1 : 100; BAL 1 : 20) with PBS containing 0·05% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBS-T). Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM, IgA, IgG, IgG1 or IgG2a (Fc specific; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) were diluted (1 : 500) in PBS-T. Antibodies were revealed with a substrate solution [o-phenylenediamine (Sigma Chemical)] in citrate–phosphate buffer (pH 5, containing 0·05% H2O2) and the reaction was stopped by the addition of H2SO4 1 M. Readings were carried out at 493 nm (VERSAmax Tunable microplate reader; MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and samples were considered negative for the presence of specific antibodies when OD493 < 0·1.

Cytokine concentration in BAL

Cytokine concentrations in BAL were measured by mouse Th1/Th2 ELISA Ready SET Go! Kit (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), including interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ as Th1-type, IL-4 and IL-10 as Th2-type cytokines. The IL-17A as a Th17-type cytokine was also measured using the ELISA kit from e-Bioscience (BD Biosciences). The sensitivity of assays for each cytokine was as follows: 4 pg/ml for IL-2, IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and 2 pg/ml for IL-4 and IL-10 and IL-17 4 pg/ml.

Respiratory challenge of immunized mice

Mice were challenged with different serotypes of S. pneumoniae as described in a previous work [16]. Briefly, freshly grown colonies of S. pneumoniae strains 3 and 14 were suspended in THB and incubated at 37°C until the log phase was reached. S. pneumoniae serotype 14 was selected as it is the one with the greatest incidence in our country, while serotype 3 is the one with the greatest virulence in our model [16]. The pathogens were harvested by centrifugation at 3600 g for 10 min at 4°C and washed three times with sterile PBS. Challenge with the two pneumococcal strains was performed 14 days after the end of each immunization protocol. Mice were challenged nasally with pathogen cells by dripping 25 µl of an inoculum containing 106 cells into each nostril. Mice were killed 48 h after challenge and their lungs were excised, weighed and homogenized in 5 ml of sterile peptone water. Homogenates were diluted appropriately, plated in duplicate on blood agar and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. S. pneumoniae colonies were counted and the results were expressed as log10 colony-forming units (CFU)/g of organ. Progression of bacterial growth to the bloodstream was monitored by blood samples obtained by cardiac puncture with a heparinized syringe. Samples were plated on blood agar and bacteraemia was reported as negative or positive haemocultures after incubation for 18 h at 37°C.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicate and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Significant differences between means were determined by analysis of variance (anova) with Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test using the StatGraphics software (Manugistics, Rockville, MD, USA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0·05.

Results

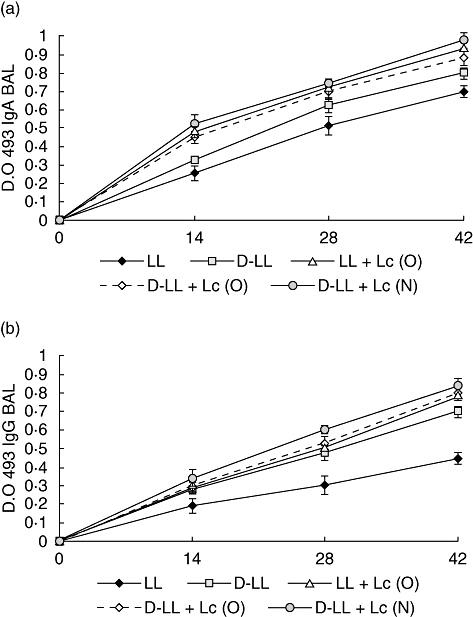

Specific anti-PppA antibodies responses in BAL: lung compartment

We evaluated administration of the probiotic strain L. casei by oral (O) and nasal (N) routes associated with nasal immunization with live (LL) and inactivated (D-LL) recombinant strains. Results are shown in Fig. 1a and b and significant differences between groups on day 42 are shown in Table 1. The D-LL + Lc (N) (IgA: P < 0·001, IgG: P < 0·01), D-LL + Lc (O) (IgA: P < 0·01, IgG, P < 0·001) and LL + Lc (O) (IgA: P < 0·05, IgG: P < 0·001) groups showed the highest levels of IgA and IgG anti-PppA in bronchoalveolar lavages in comparison with the live vaccine. D-LL + Lc (N) induced the highest IgA levels in BAL, but without significant differences with the D-LL + Lc (O) and LL + Lc (O) groups. Although D-LL induced significantly high values of specific IgA (P < 0·05) and IgG (P < 0·05) antibodies compared to live vaccine (LL), IgA values were lower than those obtained in the groups receiving the probiotic. The levels of specific anti-PppA IgM were increased slightly compared to those of LL in the groups that received Lc as an oral or nasal adjuvant associated with the inactivated vaccine, especially on day 28, although the differences were not significant (data not shown). Results showed that administration of the probiotic strain by both the oral and nasal routes exerted an important adjuvant effect on the humoral immune response in the lung compartment. This would provide an encouraging alternative for the use of vaccines involving the probiotic–inactivated recombinant bacterium association, with their associated advantages: adjuvant properties of the probiotic strain and safe application of an inactivated bacterium to human health. As expected, the groups that received only PBS, Lc (O) or Lc (N) showed no levels of specific anti-PppA antibodies.

Fig. 1.

Immunoglobulin (Ig)A (a) and IgG (b) anti-pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) antibodies response in bronchoalveolar lavages of young mice immunized nasally with recombinant live Lactococcus lactis PppA (LL), inactivated L. lactis PppA (D-LL) and live and inactivated vaccine associated with Lactobacillus casei CRL 431, administered orally (O), LL + Lc (O), D-LL + Lc (O) and nasally (N), D-LL + Lc (N). Results are expressed as the mean of the optical density (OD) ± standard deviation for each specific Ig. Antibodies were determined using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method and samples were considered negative for the presence of specific antibodies when OD 493 < 0·1.

Table 1.

Statistical comparison of immunoglobulin (Ig)A and IgG anti-pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) antibody levels between experimental groups on day 42.

| P-value for comparison between different immunization treatments (P <) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | LL + Lc (O) | D-LL | D-LL + Lc (O) | D-LL + Lc (N) | |

| IgA anti-PppA BAL | |||||

| LL | – | 0·01 | 0·05 | 0·01 | 0·001 |

| LL + Lc (O) | 0·01 | – | 0·05 | n.s. | n.s. |

| D-LL | 0·05 | 0·01 | – | 0·05 | 0·001 |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | 0·01 | n.s. | 0·05 | – | 0·05 |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 0·001 | n.s. | 0·001 | 0·05 | – |

| IgG anti-PppA BAL | |||||

| LL | – | 0·01 | 0·05 | 0·001 | 0·001 |

| LL + Lc (O) | 0·01 | – | 0·05 | n.s. | 0·05 |

| D-LL | 0·05 | 0·05 | – | 0·01 | 0·001 |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | 0·001 | n.s. | 0·01 | – | n.s. |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 0·001 | 0·05 | 0·001 | n.s. | – |

| IgA anti-PppA serum | |||||

| LL | – | n.s. | n.s. | 0·05 | 0·01 |

| LL + Lc (O) | n.s. | – | n.s. | n.s. | 0·05 |

| D-LL | n.s. | n.s. | – | n.s. | n.s. |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | 0·05 | n.s. | n.s. | – | n.s. |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 0·01 | 0·05 | n.s. | n.s. | – |

| IgG anti-PppA serum | |||||

| LL | – | n.s. | 0·05 | n.s. | 0·01 |

| LL + Lc (O) | n.s. | – | 0·05 | n.s. | 0·001 |

| D-LL | 0·05 | 0·05 | – | n.s. | 0·01 |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | – | 0·01 |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 0·01 | 0·001 | 0·01 | 0·01 | – |

Differences between means were established by analysis of variance (anova) with Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test at P < 0·05; n.s.: not significant (P > 0·05); BAL: bronchoaveolar lavage.

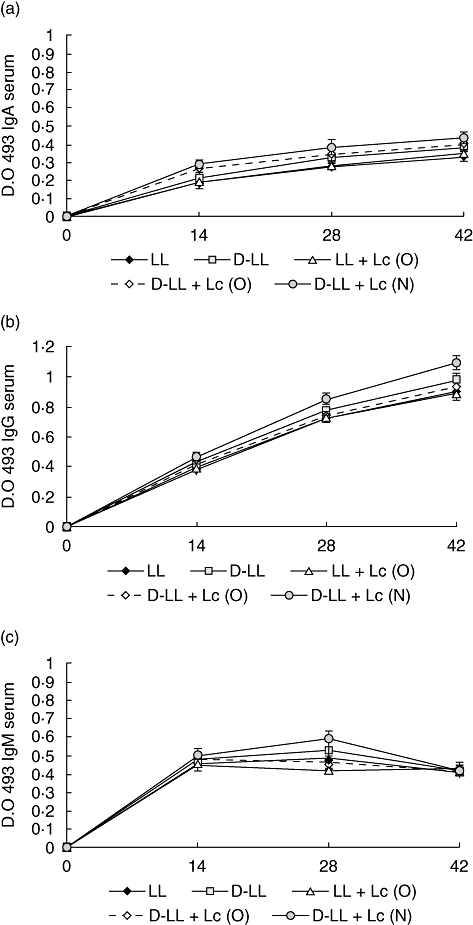

Specific anti-PppA antibody response in systemic compartments

Nasal immunization with LL induced a good response of specific IgA, IgG and IgM antibodies in serum (Fig. 2a–c). The associated administration of the probiotic by the oral route did not induce a significant increase in the levels of these specific immunoglobulins in any of the assessed groups (Fig. 2). In contrast, immunization with the inactivated recombinant strain associated with the nasal administration of the probiotic [D-LL + Lc (N)] induced a significant increase in IgG (P < 0·01 on day 42) in serum in comparison with the live vaccine (LL), showing an adjuvant effect of Lc at the systemic level compared to the D-LL group (Fig. 2b). IgM increased significantly only in the D-LL + Lc (N) group compared to LL (P < 0·05) and LL + Lc (0), but only on day 28 (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2c). The levels of IgA in serum showed no significant differences among the different groups assayed (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Antibody immune response to pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) antigen in serum after nasal immunization of young mice with recombinant live Lactococcus lactis PppA (LL), inactivated L. lactis PppA (D-LL) and live and inactivated vaccine associated with the probiotic strain Lactobacillus casei CRL 431, administered orally (O) and nasally (N). IgA (a), IgG (b) and IgM anti-PppA antibodies are shown. Results are expressed as the mean of the optical density (OD) ± standard deviation for each specific immunoglobulin. Antibodies were determined using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method and samples were considered negative for the presence of specific antibodies when OD 493 < 0·1.

Protection assays: respiratory infection in young mice with S. pneumoniae serotypes 3 and 14

In order to study whether the specific humoral immune response induced by the different immunization strategies used in this work increased resistance in mice against a pneumococcal infection, the animals were challenged intranasally with serotypes 3 and 14 of the pathogen. Analysis of the infection was carried out evaluating colonization in lung and pathogen passage into blood on day 2 after challenge (Table 2). All the treatments prevented colonization in lung by both S. pneumoniae serotypes and also prevented dissemination into the blood of serotype 14. In contrast, when animals were infected with serotype 3, only administration of the recombinant bacterium, live (LL) and dead (D-LL), associated with the oral administration of the probiotic strain Lc, prevented dissemination of the pathogen into the bloodstream. Administration of D-LL + Lc (N) did not prevent colonization of the lung by serotype 3. These results demonstrate that immunization with LL + Lc (O) and D-LL + Lc (O) would be the most effective treatment for the prevention against pneumococcal infection of young mice with S. pneumoniae.

Table 2.

Lung bacterial cell counts and haemocultures after nasal challenge of mice with two different pneumococcal serotypes.

| Serotype 3 |

Serotype 14 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Lung | Blood | Lung | Blood |

| Control | 7·8 ± 0·2a | 4·9 ± 0·2a′ | 6·7 ± 0·3a″ | 4·5 ± 0·2a° |

| LL | 3·9 ± 0·3b | < 1·5b′ | < 1·5b″ | < 1·5b° |

| D-LL | 4·2 ± 0·2b | 2·1 ± 0·4c′ | 2·2 ± 0·1c″ | < 1·5b° |

| LL + Lc (O) | < 1·5c | < 1·5b′ | < 1·5b″ | < 1·5b° |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | < 1·5c | < 1·5b′ | < 1·5b″ | < 1·5b° |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 2·1 ± 0·2d | < 1·5b′ | < 1·5b″ | < 1·5b° |

Mice were immunized with recombinant Lactococcus lactis-PppA+ live (LL) or inactivated Lactococcus lactis-PppA+ (D-LL) or in association with the oral and nasal administration of Lactobacillus casei CRL 431. Mice receiving phosphate-buffered saline were used as controls. Results are expressed as log colony-forming units (CFU)/g of lung or log CFU/ml of blood. The lower limits of bacterial detection were 1·5 log CFU/g of lung and 1·5 log CFU/ml of blood, respectively. Significant differences among groups were established by using the least significant difference test (LSD). Means in the table with different letters (a–d, a′–b′, a″–b″ or a°–b°) were significantly different (P < 0·05).

Influence of the different vaccination strategies on the production of specific IgG1 and IgG2a in both lung and systemic compartments

The effect of different treatments on the vaccine-induced immune response is important in the selection of a vaccination strategy adequate against a specific pathogen. We assessed the levels of IgG1 and IgG2a anti-PppA post-vaccination (day 42) in order to analyse the Th1/Th2 balance in both BAL and serum. Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ, associated with switching to IgG2a, while Th2 cells secrete mainly IL-4, which promotes switching to IgG1. The results obtained are shown in Table 3 and correspond to the IgG1/IgG2a ratio for each group on day 42 (2 weeks after the third immunization). Administration of LL induced a mixed-type Th1/Th2 response in BAL. The live vaccine associated with the oral administration of Lc [LL + Lc (O)] and the inactivated vaccine (D-LL) induced a significant increase in the IgG1/IgG2a ratio, indicating preferential activation of Th2 cells. In contrast, immunization with D-LL + Lc (N) and D-LL + Lc (O) showed a significant decrease in the IgG1/IgG2a ratio compared to the other groups. This would indicate that the probiotic would induce a shift towards the type Th1 response. Similar results were found in serum, although the LL + Lc (O) group did not show significant differences with LL.

Table 3.

Immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 [T helper type 2 (Th2)]/IgG2 (Th1) ratio for experimental groups assessed.

| IgG1/IG2a |

||

|---|---|---|

| Groups | BAL | Serum |

| LL | 1·55 ± 0·02a | 1·13 ± 0·03a′ |

| D-LL | 1·86 ± 0·06b | 1·29 ± 0·07a′ |

| LL + Lc (O) | 2·07 ± 0·15c | 1·24 ± 0·12a′ |

| D-LL + Lc (O) | 0·82 ± 0·07d | 0·91 ± 0·05b′ |

| D-LL + Lc (N) | 0·93 ± 0·09d | 0·95 ± 0·06b′ |

Young mice were immunized nasally with the recombinant strain, live (LL) and inactivated (D-LL), with/without the administration of Lactobacillus casei (Lc) orally (O) and nasally (N). The IgG1/IgG2a ratios were calculated 2 weeks after the third immunization (day 42). An IgG1/IgG2a > 1 ratio indicates a mixed Th1/Th2 response; while an IgG1/IgG2 < 1 ratio indicates a bias towards a Th1 response. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5–6). Significant differences among groups were established by using the least significant difference test (LSD). Means in the table with different letters (a–f or a′–b′) were significantly different (P < 0·05); BAL: bronchoaveolar lavage.

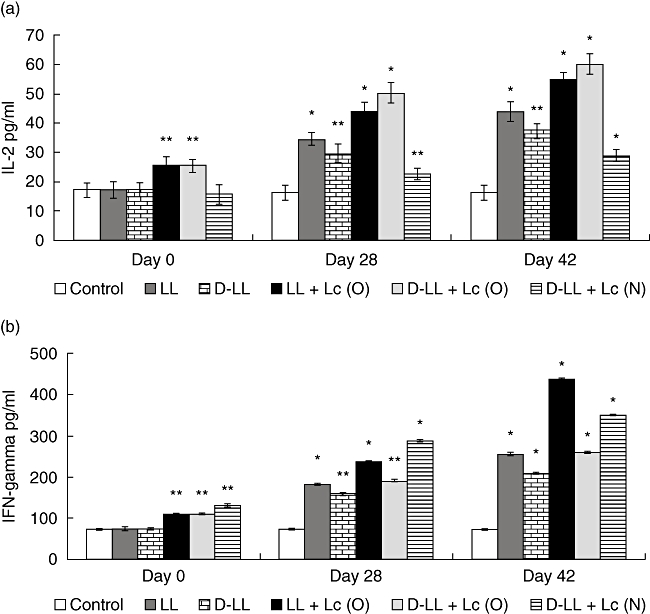

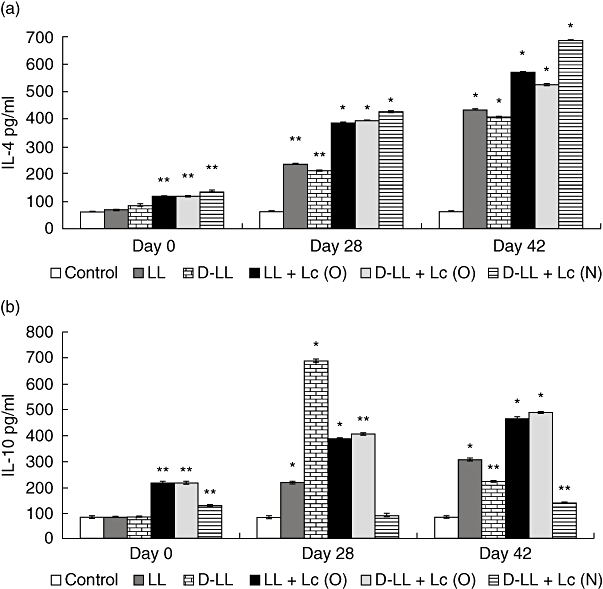

Cytokines pattern in bronchoalveolar lavages

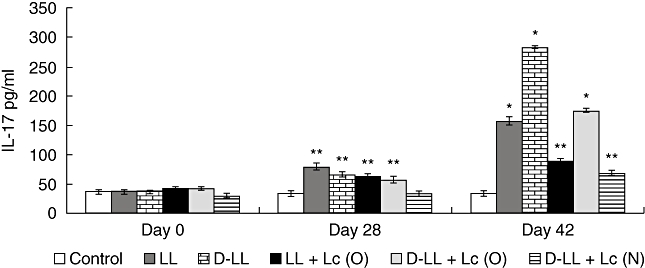

The type of immune response induced in the respiratory mucosa is decisive in the protection of the host against pathogens that enter the organism through the airways. In order to increase our knowledge of the immune cells activated by vaccination, we analysed the cytokine profile induced by the different treatments in the lung compartment (BAL), considering the balance among the three T helper cells: Th1, Th2 and Th17, of great importance in the defence against S. pneumoniae. The basal levels of cytokines and the ones induced by the oral and nasal administration of the probiotic before immunization with recombinant strains (day 0) were determined. With regard to the IL-2 and IFN-γ Th1-type cytokines (Fig. 3a, b), the mice that received L. casei by the oral and nasal routes before administration of the vaccine (day 0) showed a significant increase in IFN-γ. Oral administration of Lc induced greater production of IL-2 compared to the control that received PBS. On days 28 and 42 there was a significant increase in IL-2 and IFN-γ in BAL in all the groups treated compared to the control. LL + Lc (O) and D-LL + Lc (O) induced the highest level of IL-2, which would indicate that the probiotic influenced the increase in this cytokine compared to administration of LL [on day 42, LL versus D-LL + Lc (O): P < 0·001, LL versus LL + Lc (O): P < 0·01) and D-LL (D-LL + Lc (O) versus D-LL: P < 0·01, LL + Lc (O) versus D-LL: P < 0·001]. The concentration of IFN-γ in BAL reached highest levels in the group that received LL + Lc (O), followed by D-LL + Lc (N), with significant differences between them (LL + Lc versus D-LL + Lc (N): P < 0·01). With regard to the induction of the Th2-type cytokine IL-4, oral and nasal administration of Lc before immunization with recombinant vaccine (day 0) induced a significant increase in IL-4 in BAL compared to the control (Fig. 4a). Two weeks after the second (day 28) and third immunizations (day 42) with the recombinant strain, there was a significant increase in IL-4 in all experimental groups compared to the control (day 0). On days 28 and 42, the live and the inactivated vaccine associated with the probiotic strain administered by the oral and nasal routes induced high IL-4 levels in BAL compared to both the LL group [day 42, LL versus LL + Lc (O): P < 0·05) and the D-LL group (D-LL + Lc (O) versus D-LL: P < 0·01, D-LL versus D-LL + Lc (N): P < 0·01]. However, it should be noted that the highest levels of this cytokine, which is a marker of the stimulation of Th2 cells, was obtained with the nasal administration of the probiotic strain associated with the inactivated recombinant strain (P < 0·01). The regulatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 4b) showed variable behaviour depending upon the experimental group studied. The oral and nasal administrations of Lc induced high IL-10 concentrations compared to the control; however, the association of Lc (administered nasally) with D-LL (D-LL + Lc) induced a similar concentration to the control group on day 28. The highest IL-10 levels were reached 2 weeks after the second immunization (day 28) in the group that received D-LL (P < 0·001) compared to the control. In addition, the experimental groups that received LL + Lc (O) and D-LL + Lc (O) induced medium levels of IL-10, followed by LL, while the lowest levels were obtained with nasal immunization with the inactivated recombinant bacterium associated with nasal administration of the probiotic strain [D-LL + Lc (N) when compared with other immunized groups (D-LL + Lc (O) versus D-LL + Lc (N): P < 0·01; versus LL + Lc (O): P < 0·01; versus LL: P < 0·05; versus D-LL: P < 0·001]. This result is important, because low IL-10 levels would compromise regulation of the host defence response against an infectious challenge, a point dealt with below. IL-17A, which represents activation of the Th17 cells, also showed a variable pattern depending on the experimental group and on the days considered post-immunization (Fig. 5). On day 0 (before immunization), neither oral nor nasal administrations of Lc for 2 days was able to induce an increase in IL-17A levels in BAL. On day 28 (2 weeks after the second immunization), LL (P < 0·01) induced high IL-17 levels compared to control, the same as the D-LL (P < 0·01), LL + Lc (O) (P < 0·05) and D-LL + Lc (O) (P < 0·05) groups. In contrast, nasal administration of the probiotic associated with inactivated vaccine [D-LL + Lc (N)] induced lower levels than those of the control. The highest IL-17 concentration was obtained 2 weeks after the third immunization (day 42) and the highest level of this cytokine was induced in the D-LL group compared to the control and to the other groups [D-LL versus D-LL + Lc (N): P < 0·01; versus LL: P < 0·05; LL + Lc (O): P < 0·001, versus D-LL + Lc (O): P < 0·05]. Interestingly, on day 42 D-LL, associated with the oral administration of the probiotic [D-LL + Lc (O), P < 0·001], induced concentrations similar to those induced by administration of the live vaccine, while the association of Lc with live vaccine [LL + Lc (O)] induced significantly lower values than those of live vaccine alone [LL + Lc (O) versus LL: P < 0·05].

Fig. 3.

T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines production in bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) of young mice stimulated with recombinant Lactococcus lactis-pneumococcal protective protein A (PppA) strains: live (LL), inactivated (D-LL) and in association with the probiotic Lactobacillus casei (Lc) administered orally (O) and nasally (N): LL + Lc (O), D-LL + Lc O) and D-LL + Lc (N). Probiotic administration of Lc (O) and Lc (N) was evaluated. Non-stimulated young mice were also evaluated as controls of basal cytokine levels (control). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Significantly different from the control group: *P < 0·01, **P < 0·001.

Fig. 4.

Bronchoalveolar T helper type 2 (Th2) cytokines production by young mice immunized with different groups of recombinant live and inactivated vaccine and probiotic strain (see Fig. 3 for details).

Fig. 5.

Bronchoalveolar interleukin (IL)-17A production by young mice immunized with different groups of recombinant vaccine and probiotic strain (see Fig. 3 for details).

Discussion

S. pneumoniae infection continues to represent a serious public health problem because of its high morbidity and mortality rates, especially in developing countries. In Latin America, approximately 20 000 children die every year because of this bacterium. In Argentina there are 20 000 annual cases of pneumonia in children below 2 years of age, with a mortality of 1%, as reported by the Sociedad Latinoamericana de Infectología Pediátrica (Latin American Pediatric Infectology Association) (http://www.apinfectologia.org/?module=noticias¬a=196) in 2008. Because of its high cost, the conjugate vaccine used in developed countries is not included in the vaccination calendar in Argentina. This is why there is a pressing need for the search for new inexpensive vaccination strategies for at-risk populations that can afford protection against the serotypes of greatest incidence in our country. The world trend is towards the design of mucosal vaccines, because they are practical and non-invasive and are effective for the induction of an adequate response at both mucosal and systemic levels. An alternative explored by some researchers in relation to the prevention of infections caused by S. pneumoniae is the use of LAB as carriers of different pneumococcal antigens. In previous studies we have demonstrated that immunization with PppA, expressed as a wall-anchored protein on the surface of L. lactis, was able to induce cross-protective immunity against different pneumococcal serotypes, afforded protection against both systemic and respiratory pneumoccocal challenges, and induced protective immunity in adult and infant mice [16]. Additionally, on the basis of previous studies, we have demonstrated that the nasal route is the best alternative for protection against a pneumococcal infection using L. lactis as adjuvant [14,15] and as antigen delivery vehicle [16,31]. This agrees with the findings of other researchers who demonstrated the convenience of the nasal route for the immunization of mucosae against respiratory pathogens [32,33].

In this work we have assessed new immunization strategies using an inactivated recombinant bacterium by itself and in association with a probiotic strain. Analysis of the immunostimulatory properties of non-viable LAB strains showed that they depend upon the strain used, although there is evidence indicating that viable bacteria are more effective for mucosal immunostimulation. In most cases, heat-killed strains were assessed in which differences in immunostimulation might be associated with heat-induced alteration of epitopes [34]. In order to conserve the structure of the PppA expressed in the surface of L. lactis, death was carried out by chemical inactivation. The inactivated strain proved to be effective for the induction of high levels of specific IgA and IgG antibodies in BAL and of IgG in the serum of the vaccinated young mice, which were higher than those obtained with the live vaccine. The association of the live and dead vaccines with the probiotic increased specific anti-PppA antibodies, reaching maximum values in the D-LL + Lc (N) group. The increase in IgA and IgG anti-PppA is of fundamental importance at the lung level, because while IgA prevents pathogen attachment to epithelial cells, thus reducing colonization, IgG would exert protection at the alveolar level, promoting phagocytosis and preventing local dissemination of the pneumococcus and its passage into blood [35]. We demonstrated that the vaccine-induced humoral immune response was increased in all assessed groups at both the lung and systemic compartments, although the highest levels of specific antibodies were obtained when the vaccine, dead or live, was associated with the probiotic. This was coincident with the increase in IL-4 in the lung compartment, indicating activation of the Th2 cell population, which enhanced the humoral immune response. Recent reports have shown that certain lactobacilli improved the specific antibody response after vaccination against some viral and bacterial pathogens [21,36]. In addition, L. casei 431 administered orally is able to induce an increase in IgA+ cells in the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) [26,37], and it seems likely that stimulation at the level of the nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) exerts a similar effect when the probiotic is administered by the nasal route, favouring IgA production at the lung level. At present, studies are being carried out in the nasopharynx to analyse the immune mechanisms induced at this level by the recombinant vaccine and by the probiotic strain. On the other hand, analysis of the IgG1/IgG2a ratio revealed that there exist differences in the specific IgG subtype induced for each immunization protocol. Thus, although the two anti-PppA IgG subtypes were induced with all the treatments assayed, when the probiotic was used as an oral and nasal adjuvant associated with the inactivated vaccine the cellular response became polarized towards the predominance of Th1 cells, as shown by an IgG1/IgG2a ratio < 1. The effectiveness of anti-PppA antibodies induced by vaccination was demonstrated by passive immunization in a previous study [16]. Our results demonstrated that only vaccination with the live and dead recombinant strains associated with oral administration of the probiotic was able to prevent lung colonization and the dissemination into blood of the two serotypes assessed (3 and 14). Recently it was shown that IgG2a has a great ability to mediate complement deposition on the pneumococcal surface [38], which would account partly for the protection afforded by vaccination with D-LL + Lc (O), but not the results obtained for administration of D-LL + Lc (N), which enabled the lung colonization of serotype 3. In the LL and D-LL groups high IgG1 production would interfere with the complement-fixing activity of the IgG2a anti-PppA and would partly explain the lung colonization (serotypes 3 and 14) and the passage into blood (serotype 14) of the pathogen. This was not found in the LL + Lc (O) group, in which IgG1 production was favoured, and there was full protection. In this sense, IgG1 contributes to protection against pneumococcal infection through Fc receptor binding or by preventing attachment and colonization of the pathogen on mucosal surfaces. The participation of specific humoral immunity in protection against S. pneumoniae is undeniable, although recent reports have indicated that T CD4+ cells would also play a relevant role in the host's defences against pneumococcal infections [39]. In order to increase our knowledge concerning the possible mechanisms involved in vaccine-induced protective immunity, we assessed the cytokines that characterize different CD4+ T cell populations. Th1, IL-2 and IFN-γ cytokines were increased in all the assessed groups, although the profiles induced for each immunization showed important differences. Thus, LL + Lc (O) induced high levels of both interleukins (IL-2 and IFN-γ), while D-LL + Lc (O) induced mainly an increase in IL-2 and D-LL + Lc (N) in IFN-γ. Oral and nasal administration of L. casei showed a similar pattern of these Th1 cytokines and would have an influence on the results when associated with the vaccine. IL-2 would exert a strong influence on the proliferative capacity and maintenance of memory T cells [40], which would be a desirable characteristic in the selection of an efficacious long-term vaccine. Some lactobacilli used as adjuvants in vaccination protocols increased systemic protection through an increase in the Th1 response [19]. In addition, an immune response based on the Th1 population participates actively in the resolution of S. pneumoniae infection in humans [41]. Considering our results, the probiotic strain would exert an immunostimulatory effect on the Th1 cells and on the release of their cytokines in the lung. On the other hand, regulation of the inflammatory response is most important in infectious diseases. In this sense, the probiotic administered by the oral and nasal routes was able to increase the regulatory Th2 IL-10 cytokine. This would be of great importance to ensure a balanced immune response that would enable resolution of the infectious process, limiting a possible exacerbated inflammatory response and avoiding damage to the host's tissues. The greatest IL-10 production was obtained on day 42 in the groups that received the live and inactivated vaccine associated with orally administered L. casei. In contrast, the nasal administration of Lc and D-LL + Lc induced an IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio > 1, which could have negative implications for the host after infection if the Th1 response was exacerbated. However, other factors must be considered. Thus, recent works have associated IL-17 with stimulation in the production of chemokines capable of recruiting IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells [42,43]. In addition, IL-17 and IL-22 produced by Th17 induce the attraction of neutrophils and macrophages into the parenchymal tissue, favouring pathogen clearance [44]. It was also demonstrated that this cytokine, being a key factor in the adaptive immunity against the above pathogen, would mediate the death of pneumococci in the presence or absence of specific antibodies [45]. Moreover, using knock-out mice, IL-17 was shown to be of fundamental importance to reduce nasal colonization by S. pneumoniae. Oral and nasal administration of L. casei in association with LL vaccination induced the highest IL-17 levels. It also increased IL-2 and IFN-γ cytokine levels and afforded full protection against pneumoccocal challenge. In contrast, the dead vaccine failed to prevent pneumococcal colonization by both serotypes 3 and 14 of the pathogen, although it induced high IL-17 and Th1 cytokine levels, indicating the complexity of the protective response. On the other hand, it should be pointed out that too-high levels of IL-17 could be associated with autoimmunity [44], so that a balanced response is desirable after vaccination. In view of these facts, D-LL + Lc (N) may have failed to prevent lung colonization by the more virulent pneumococcal serotype because the induction of IL-17 and IL-10 was not as high as in the other groups. This could be due to the inhibitory effect exerted by the high IL-4 and IFN-γ levels induced by D-LL + Lc (N) [44,46]. Although the combination of LL + Lc (O) was effective in protection against infectious challenge, the safety implied by the use of a dead recombinant strain makes D-LL + Lc (O) the strategy of choice for potential use in humans. Nasal vaccination with the inactivated strain associated with L. casei administered by the oral route would favour the induction of not only protective specific antibodies, but also of specific CD4+ T cells. The full protection exerted by D-LL + Lc (O) would be the result of a balanced humoral and cellular immune response between the protective antibodies and the CD4+ Th1, Th17 and Th2 cells specific for the PppA antigen. Oral administration of the probiotic strain associated with both the live and inactivated vaccines induced an evident improvement in the host's defences because it prevented lung colonization with the even more virulent serotype. At present, further studies at both the lung and nasopharyngeal levels are being carried out in order to establish the scientific bases that will permit the application of D-LL + Lc (O) to human health. As far as we know, this is the first report that demonstrates the efficacy of the use of a probiotic and an inactivated recombinant strain as a vaccination strategy that is effective, relatively inexpensive and with high application feasibility in Argentina.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms Mabel Taljuk for her cooperation in bibliography search. This work was supported by grants from CONICET: Res. 1257/4, PIP 6248, FONCyT: PICT 33754 and CIUNT: D/403.

Disclosure

All authors report no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Constenla D. Evaluating the costs of pneumococcal disease in selected Latin American countries. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2007;22:268–78. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892007000900007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch JP, Zhanel GG. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:189–209. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singleton RJ, Hennessy TW, Bulkow LR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes among alaska native children with high levels of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage. JAMA. 2007;297:1825–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsurahara T, Hotomi M, Yamauchi K, Billal DS, Yamanaka N. Protection against systemic fatal pneumococcal infection by maternal intranasal immunization with pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:393–8. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogunniyi AD, Grabowicz M, Briles DE, Cook J, Paton JC. Development of a vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease based on combination of virulence proteins of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2007;75:350–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01103-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Li D, Gong Y, et al. Caseinolytic protease: a protein vaccine which could elicit serotype-independent protection against invasive pneumococcal infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujihashi K, Koga T, Van Ginkel FW, Hagiwara Y, McGhee JR. A dilemma for mucosal vaccination: efficacy versus toxicity using enterotoxin-based adjuvants. Vaccine. 2002;20:2431–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vliagoftis H, Kouranos VD, Betsi GI, Falagas ME. Probiotics for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:570–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60219-0. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michail SK, Stolfi A, Johnson T, Onady GM. Efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:508–16. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim IS, Lee HS, Kim WY. The effect of lactic acid bacteria isolates on the urinary tract pathogens to infants in vitro. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(Suppl. S):57–62. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz Y, Nadal I, Sánchez E. Probiotics as drugs against human gastrointestinal infections. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2007;2:148–56. doi: 10.2174/157489107780832596. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Moreno De LeBlanc A, Perdigon G. Yoghurt feeding inhibits promotion and progression of experimental colorectal cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bibiloni R, Fedorak RN, Tannock JW, et al. DSL #3 probiotics mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1539–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina M, Villena J, Salva S, Vintiñi E, Langella P, Alvarez S. Nasal administration of Lactococcus lactis improves local and systemic immune responses against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiol Immunol. 2008;52:399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villena J, Medina M, Vintiñi E, Alvarez S. Stimulation of respiratory immunity by oral administration of Lactococcus lactis. Can J Microbiol. 2008;54:630–38. doi: 10.1139/w08-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina M, Villena J, Vintiñi E, Hebert EM, Raya R, Alvarez S. Nasal immunization with Lactococcus lactis expressing the pneumococcal protective protein A induces protective immunity in mice. Infec Immun. 2008;76:2696–705. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00119-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green BA, Zhang AY, Masi W, et al. PppA, a surface-exposed protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, elicits cross-reactive antibodies that reduce colonization in a murine intranasal immunization and challenge model. Infect Immun. 2005;73:981–89. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.981-989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanniffy SB, Carter AT, Hitchin E, Wells JM. Mucosal delivery of a pneumococcal vaccine using Lactococcus lactis affords protection against respiratory infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:185–93. doi: 10.1086/509807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olivares M, Diaz-Ropero M, Sierra S, et al. Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition. 2007;23:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vrese M, Rautenberg P, Laue C, Koopmans M, Herremans T, Schrezenmeir J. Probiotic bacteria stimulate virus-specific neutralizing antibodies following a booster polio vaccination. Eur J Nutr. 2005;44:406–13. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West CE, Gothefors L, Granstrom M, Kayhty H, Hammarstrom ML, Hernell O. Effects of feeding probiotics during weaning on infections and antibody responses to diphtheria, tetanus and Hib vaccines. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maassen CB, Van Holten-Neelen C, Balk F, et al. Strain-dependent induction of cytokine profiles in the gut by orally administered Lactobacillus strains. Vaccine. 2000;18:2613–23. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamadzadeh M, Olson S, Kalina WV, et al. Lactobacilli activate human dendritic cells that skew T cells toward T helper 1 polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500098102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina M, Izquierdo E, Ennahar S, Sanz Y. Differential immunomodulatory properties of Bifidobacterium logum strains: relevance to probiotic selection and clinical applications. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:531–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vintiñi E, Alvarez S, Medina M, Medici M, De Budeguer MV, Perdigón G. Gut mucosal stimulation by acid lactic bacteria. Biocell. 2000;24:223–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Racedo S, Villena J, Medina M, Agüero G, Rodríguez V, Alvarez S. Lactobacillus casei administration reduces lung injuries in a Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:2359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villena J, Racedo S, Agüero G, Bru E, Medina M, Alvarez S. Lactobacillus casei improves resistance to pneumococcal respiratory infection in malnourished mice. J Nutr. 2005;135:1462–69. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez S, Herrero C, Bru E, Perdigon G. Effect of Lactobacillus casei and yogurt administration on prevention of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in young mice. J Food Prot. 2001;64:1768–74. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.11.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agüero G, Villena J, Racedo S, Haro C, Alvarez S. Beneficial immunomodulatory activity of Lactobacillus casei in malnourished mice pneumonia: effect on inflammation and coagulation. Nutrition. 2006;22:810–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings DJ, Kusy AR. Thymineless death in Escherichia coli: deoxyribonucleic acid replication and the immune state. J Bacteriol. 1970:106–17. doi: 10.1128/jb.102.1.106-117.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villena J, Medina M, Raya R, Alvarez S. Oral immunization with recombinant Lactococcus lactis confers protection against respiratory pneumococcal infection. Can J Microbiol. 2008;54:845–53. doi: 10.1139/w08-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira ML, Arêas AP, Campos IB, et al. Induction of systemic and mucosal immune response and decrease in Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization by nasal inoculation of mice with recombinant lactic acid bacteria expressing pneumococcal surface antigen A. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1016–24. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos IB, Darrieux M, Ferreira DM, et al. Nasal immunization of mice with Lactobacillus casei expressing the pneumococcal surface protein A: induction of antibodies, complement deposition and partial protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae challenge. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:481–8. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galdeano CM, Perdigón G. Role of viability of probiotic strains in their persistence in the gut and in mucosal immune stimulation. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:673–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Twigg HL., III Humoral immune defense (antibodies): recent advances. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:417–21. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-089JS. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivares M, Díaz-Ropero MP, Sierra S, et al. Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition. 2007;23:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perdigon G, Alvarez S, Medina M, Vintiñi E, Roux E. Influence of the oral administration of lactic acid bacteria on IgA producing cells associated to bronchus. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 1999;12:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferreira DM, Darrieux M, Oliveira ML, Leite LC, Miyaji EN. Optimized immune response elicited by a DNA vaccine expressing pneumococcal surface protein a is characterized by a balanced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1)/IgG2a ratio and proinflammatory cytokine production. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:499–505. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00400-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao J, Gong Y, Li D, et al. CD4(+) T lymphocytes mediated protection against invasive pneumococcal infection induced by mucosal immunization with ClpP and CbpA. Vaccine. 2009;27:2838–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foulds KE, Wu CY, Seder RA. Th1 memory: implications for vaccine development. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00400.x. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemp K, Bruunsgaard H, Skinhøj P, Klarlund Pedersen B. Pneumococcal infections in humans are associated with increased apoptosis and trafficking of type 1 cytokine-producing T cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5019–25. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5019-5025.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stockinger B, Veldhoen M, Martin B. Th17 T cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.008. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–77. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo V, Bettelli E. Th17 cells: effector T cells with inflammatory properties. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:362–71. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.007. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu YJ, Gross J, Bogaert D, et al. Interleukin-17A mediates acquired immunity to pneumococcal colonization. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000159. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]