Abstract

Cationic nucleoside lipids based on a 3-nitropyrrole universal base were prepared from D-ribose using a straightforward chemical synthesis. Several studies including DLS, TEM and ethidium bromide (EthBr) assay demonstrated that these amphiphilic molecules form supramolecular organizations of nanometer size in aqueous solutions and are able to bind nucleic acids. siRNA knockdown experiments were performed with these nucleolipids and we observed protein knockdown activity similar to the siPORT NeoFX positive control. No significant cytotoxicity was found.

Nucleolipids --amphiphiles possessing both nucleic acid recognition and lipophilic alkyl chains components-- are emerging as both tools for constructing supramolecular assemblies and for nucleic acid delivery.(1–13) The area of nucleic acid delivery is particularly interesting, since gene delivery provides a mechanism to introduce new genes in cells for basic in vitro research experiments as well as to replace or supplement a defective or missing gene in a patient as part of a clinical therapy.(14–20) Consequently, synthetic lipids, as well as other DNA carriers such as calcium phosphate particles, dendrimers, or surface-mediated assemblies(21), are highly sought-after. Minimally toxic to cells, these lipids also afford high DNA or RNA transfection activity. Recently, we have reported the synthesis and transfection activity of a series of cationic and glycosylated nucleolipids which are both nontoxic and active DNA transfection agents.(11) (13) In an ongoing effort to expand the scope and properties of this family of lipids we are 1) synthesizing analogs where the thymine nucleobase is replaced by the synthetic 3-nitropyrrole universal base, and 2) evaluating the potential of these nucleolipids for siRNA delivery. Herein, we report the synthesis, physico-chemical properties, and siRNA transfection efficiency of a universal-base nucleolipid, the tosylate salt of 1-(2’, 3’-dioleyl-5’-trimethylammonium-(α,β)-D-ribofuranosyl)-3-nitropyrrole.

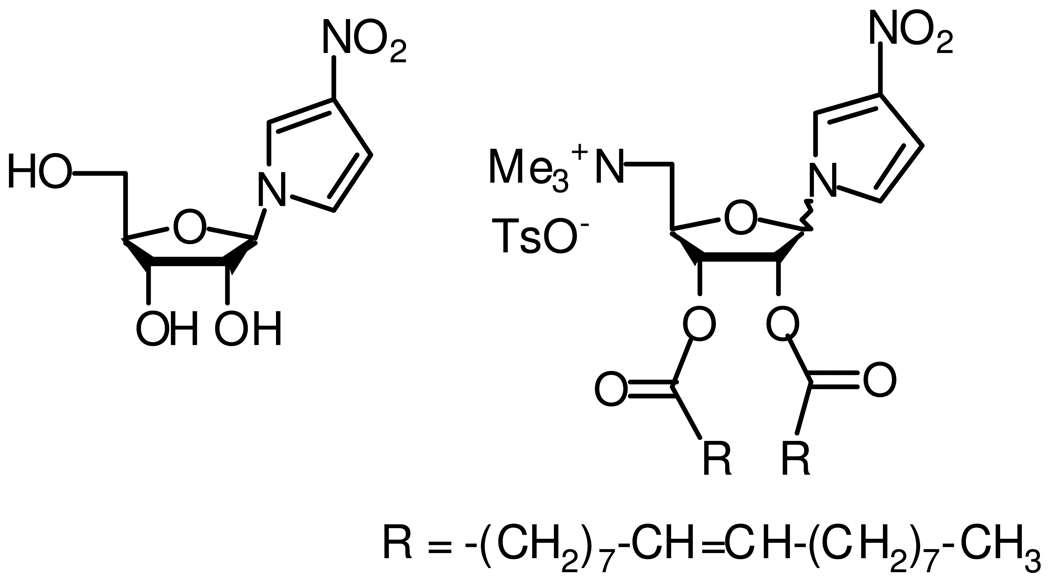

The target nucleolipid, 7, is shown in Figure 1, which possesses three key components: a quaternized amine at the 5’ position, two oleic acid chains linked at the 2’ and 3’ positions, and a 3-nitropyrrole attached at the anomeric position. The cationic charge is responsible for electrostatic binding to the nucleic acids and the oleyl chains contribute to stabilization of the resulting nucleic acid-nucleolipid assembly through hydrophobic chain-chain interactions. The 3-nitropyrrole, which is perhaps the best characterized universal base analogue, was introduced to circumvent the restrictive hydrogen bonding pattern controlling typical purine-pyrimidine hydrogen motifs by incorporating the weakly hydrogen bonding nitro substituent.(22–24) It is known that the 3-nitropyrrole group can form complementary base-pairs with all four natural bases without significantly destabilizing neighboring base-pair interactions. As a result, it has been used for diverse applications including hybridization of DNA duplexes, oligonucleotide probes and primers, peptide nucleic acids, and sequencing by MALDI mass spectrometry.(25)

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the universal nucleobase and nucleolipid (tosylate salt of 1’-(2’,3’-dioleyl-5’-trimethylammonium-α β–D-ribofuranosyl)-3-nitropyrrole).

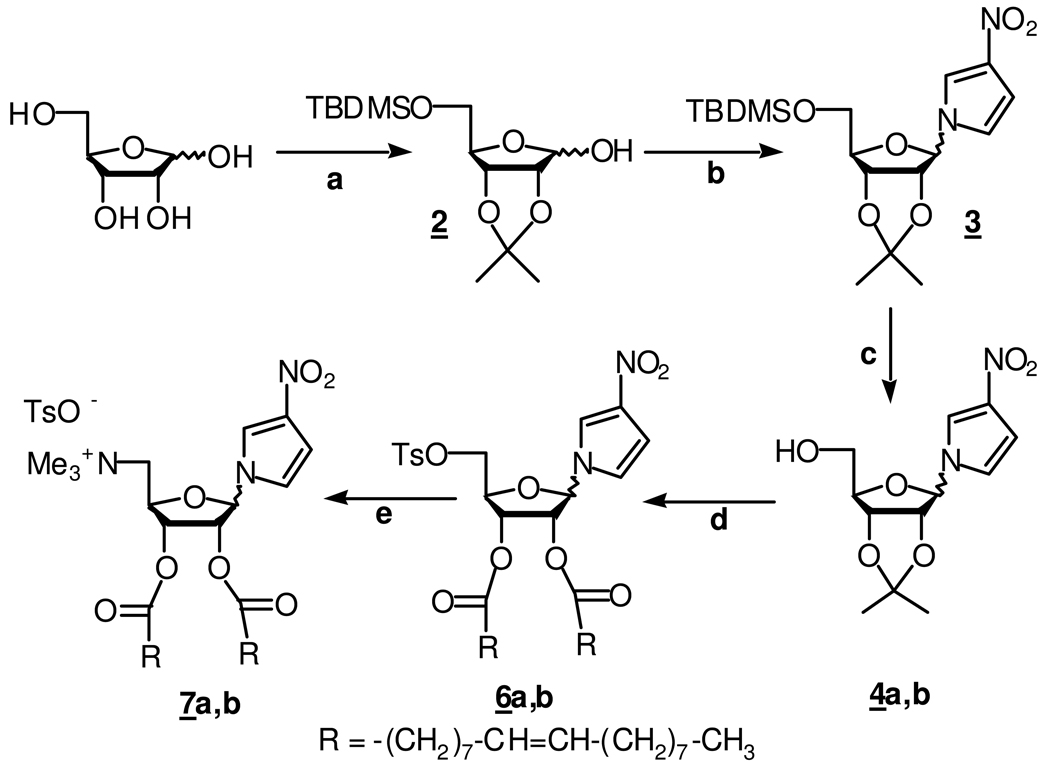

The alpha and beta anomers of 1’-(2’,3’-dioleyl-5’-trimethylammonium–D-ribofuranosyl)-3-nitropyrrole, 7a and 7b, respectively, were synthesized from D-ribose as shown in Scheme 1. Briefly stated, 5-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-2, 3-O-isopropylidene-D-ribose, 2, was prepared in two steps from D-ribose following a published procedure.(26) Next, the stereoselective chlorination of the protected sugar, 2, with CCl4 and hexamethylphosphorus triamide (HMPT)(27) was followed by coupling with the anion of 3-nitropyrrole formed from the commercially available 1-(triisopropylsilyl)pyrrole.(28) Deprotection of the resulting derivative 3 afforded the mixture of (α) 4a (53%) and (β) 4b (18%) anomers with the (α) form as the major isolated polar isomer. The relative stereochemistry of these compounds was assigned by NOESY and COSY experiments (data not shown). Compounds 4a and 4b were then separately tosylated with TsCl/TEA to give 5a and 5b (structures not shown), deprotected with TFA/H2O, and coupled with oleic acid using DCC/DMAP to afford the nucleo-lipids 6a and 6b. Finally, 6a and 6b were reacted with trimethylamine for two days in a sealed tube to afford the nucleolipids 7a and 7b. The complete characterization data, including 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and elemental analysis, can be found in the SI. A differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) trace of the hydrated nucleolipid 7a or 7b shows no phase-transition temperature from −40 °C to 80 °C.

Scheme 1.

Reaction conditions: (a) (i) acetone, CuSO4, 94% yield, (ii) TBDMSCl, DMAP, TEA 35% yield; (b) (i) CCl4, HMPT, (ii) 3-nitropyrrole, NaH, CH3CN, 40% yield; (c) TBAF dry THF, 71% yield, α/β3:1; (d) (i) TsCl, TEA, DCM 5a (94% yield), 5b (56% yield)) (ii) TFA/H2O, quant. (iii) Oleic acid, DCC/DMAP, 6a (77% yield), 6b (87% yield); (e) NMe3, CH3CN 60°C, 40 hrs, 7a and 7b quant. yields.

Next, to determine whether the universal base nucleolipids 7a and 7b bind nucleic acids, we performed a standard ethidium bromide fluorescence displacement assay with calf-thymus DNA as a model system.(29) DNA binding was observed for 7a and 7b as the fluorescence intensity decreased rapidly (see S.I. for curves and details). The nucleolipids formed a 6:1 and 2:1 complex for 7a and 7b with a binding constant of ≈ 10−7 M, −1 similar in magnitude to DOTAP.(30) This universal base, 3-nitropyrrole, was expected to bind DNA or RNA based on the published data. Previous thermal denaturation studies with 1-(2’-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranosyl)-3-nitropyrrole showed that this base pairs with the four naturally occurring bases with little discrimination.(31, 32) The nitro group of 3-nitropyrrole polarize the π–aromatic system enhancing the π–stacking interactions, and yet as a poor hydrogen bond participator it does not distinguish between the bases. Considering the minor differences between DNA and siRNA in terms of base composition and ability to hydrogen bond and from π-stacking arrangements, the 3-nitropyrrole base is likely to interact with the bases of siRNA as well as DNA.

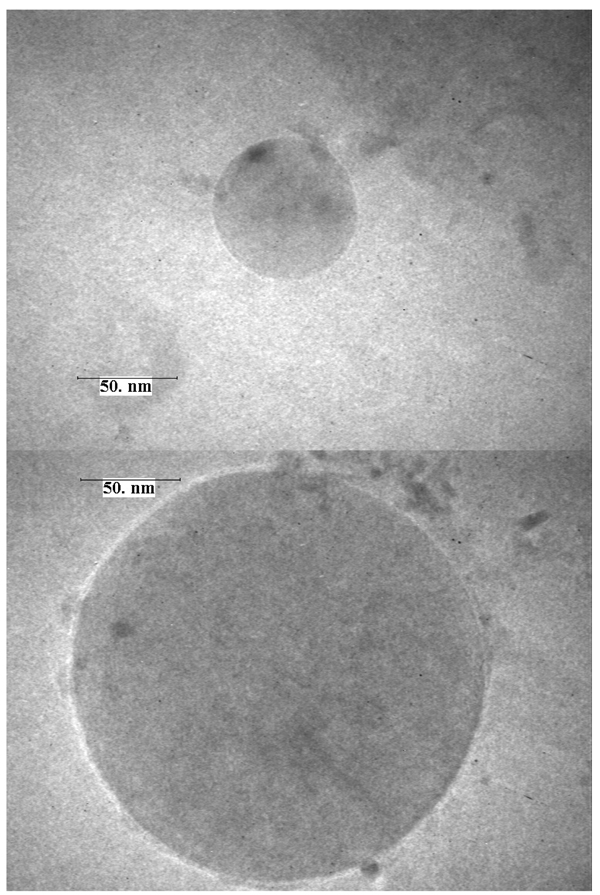

As 7a and 7b are amphiphilic, the dispersion of these nucleolipids in water by sonication leads to vesicles in the presence and absence of DNA. Again DNA was used as a model system. In the absence of DNA, vesicle size, as measured by DLS, was 84.7 nm and 458.4 nm for compounds 7a and 7b respectively. For 7b we observed a broad distribution of vesicle sizes. In the presence of DNA, and at different compound/DNA charge ratios, lipoplexes were formed of 132.4 nm (7a/DNA 2:1), 179.3 nm (7a/DNA 5:1), and 469.8 nm (ratio 7b/DNA 2:1), 516.1 nm (ratio 7b/DNA 5:1). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments were performed on vesicle samples 7a and 7b using a Philips CM 10 (negative staining with ammonium molybdate 1% water, Cu/Pd carbon coated grids). Both anomers (α and β) of the nucleolipids formed small vesicles. Representative images of vesicles formed by 7a and 7b with diameters of roughly 80 nm and 220 nm respectively are shown in Figure 2. Similar experiments performed with vesicles formed from nucleolipid-DNA solutions were inconclusive as to the location of the DNA within the structure.

Figure 2.

TEM image of single isolated vesicles obtained with 7a (top) and 7b (bottom).

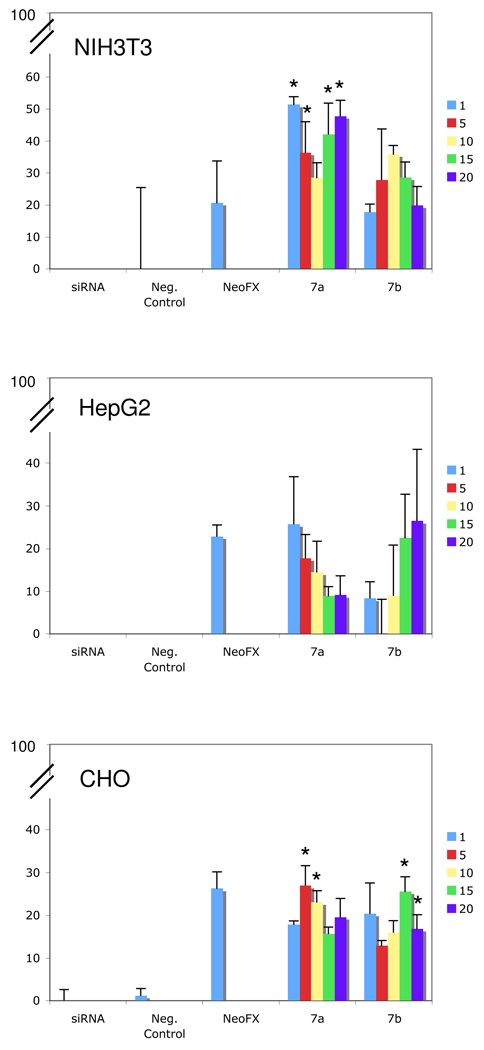

The transfection of siRNA with 7a and 7b was next performed to evaluate the reduction in protein synthesis. Experiments were performed using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) siRNA (Ambion). Complete details can be found in the SI and the transfection experiments were performed in the presence of serum. Three distinct cell lines were used, including human liver (HepG2), mouse fibroblast (NIH 3T3), and Chinese Hamster Ovarian (CHO) cells. siRNA transfection results were accessed after 48h as a function of both anomer and cation /anion (N/P) mole ratio, and the experiments were performed in serum-containing media. In each experiment, controls using GAPDH siRNA and negative control siRNA were used at 30 mM. siPORT NeoFX was used as the positive control. As shown in Figure 3, siRNA knockdown was observed for both nucleolipids in the three different cell lines, with values comparable, not significantly significant, to the positive control - NeoFX. The transfection activity of 7a was significant vs siRNA (p<0.05) in NIH 3T3 and CHO cells with N/P ratios of 1, 5, 15, and 20 and 1 and 5, respectively. The transfection activity of 7b was significant vs siRNA (p<0.05) in CHO cells with N/P ratios of 15 and 20, respectively. The configuration of the anomeric position does not have a significant role on the transfection. In addition, none of the nucleolipids showed a significant cytotoxicity at this concentration using an MTS assay with CHO cells as the viability was similar to the negative control (data no shown).

Figure 3.

siRNA transfection results after 48h in HepG2, NIH 3T3, and CHO cells as a function of nucleolipid (7a and 7b) and N/P mole ratio. N = 3; * p< 0.05 vs siRNA control.

In summary, we have synthesized and characterized a new universal base nucleolipid for siRNA delivery. The nucleolipids possess a cationic charge, a 3-nitropyrrole base, and two oleyl chains, and these lipids form vesicles in the presence and absence of nucleic acids. siRNA delivery and resulting protein knockdown was observed in three separate cell lines: hamster ovarian, mouse fibroblast, and human liver cells. This is the first report of such activity with a nucleolipid. Work is in progress to synthesize additional universal nucleolipids (including the nitroindole and nitroimidazole analogues for siRNA delivery), as well as to develop a structure-activity relationship. Nucleolipids are one of the newest types of synthetic lipid vectors being explored and, like others in the lipid family, offer the potential advantages of ease of synthesis, carriers of large and small nucleic acid payloads, and minimal toxicity.(11, 14–17, 33–42). The synthesis and evaluation of new lipids that possess unique head groups, backbones, or hydrophobic chains for nucleic acid binding and/or self-assembly will facilitate the identification of optimal carriers for nucleic acids in vitro and in vivo; efforts in this area should be encouraged and promoted.

Supplementary Material

Synthesis, characterization data, transfection studies, and cell cytotoxicity data. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

PB acknowledges financial support from the Army Research Office. MWG acknowledges support from BU and the NIH. The authors also thank Pascal Raynal for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Gissot A, Camplo M, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Nucleoside, nucleotide and oligonucleotide based amphiphiles: A successful marriage of nucleic acids with lipids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:1324–1333. doi: 10.1039/b719280k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milani S, Baldelli Bombelli F, Berti D, Baglioni P. Nucleolipoplexes: A new paradigm for phospholipid bilayer-nucleic acid interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11664–11665. doi: 10.1021/ja0714134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuomo F, Lopez F, Ruggero A, Colafemmina G, Ceglie A. Nucleotides and nucleolipids derivatives interaction effects during multi-lamellar vesicles formation. Colloids and Surfaces, B: Biointerfaces. 2008;64:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreau L, Camplo M, Wathier M, Taib N, Laguerre M, Bestel I, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Real time imaging of supramolecular assembly formation via programmed nucleolipid recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14454–14455. doi: 10.1021/ja805974g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bestel I, Campins N, Marchenko A, Fichou D, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Two dimensional self-assembly and complementary base pairing between amphiphile nucleotides on graphite. J. Coll. Interface Sci. 2008;323:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau L, Barthélémy P, Maataoui ME, Grinstaff MW. Supramolecular assemblies of nucleoside-based amphiphiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7533–7539. doi: 10.1021/ja039597j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreau L, Ziarelli F, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Self-assembled microspheres from f-block elements and nucleoamphiphiles. Chem. Comm. 2006;15:1661–1663. doi: 10.1039/b601038e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreau l, Campins N, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. A fluorocarbon nucleoamphiphile for the construction of actinide loaded microspheres. Tet. Lett. 2006;47:7117–7120. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthélémy P, Prata CAH, Filocamo SF, Immoos CE, Maynor BW, Hashmi SAN, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. Supramolecular assemblies of DNA with neutral nucleoside amphiphiles. Chem. Comm. 2005:1261–1263. doi: 10.1039/b412670j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campins N, Dieudonné P, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Nanostructured assemblies from nucleotide based amphiphiles. New. J. Chem. 2007;31:1928–1934. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabaud P, Camplo M, Payet D, Serin G, Moreau L, Barthélémy P, Grinstaff MW. Cationic nucleoside lipids for gene delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:466–472. doi: 10.1021/bc050162q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreau L, Barthélémy P, Li Y, Luo D, Prata CAH, Grinstaff MW. Nucleoside phosphocholine amphiphile for in vitro DNA transfection. Molecular BioSystems. 2005;1:260–264. doi: 10.1039/b503302k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arigon J, Prata CAH, Grinstaff MW, Barthélémy P. Nucleic acid complexing glycosyl nucleoside-based amphiphile. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:864–872. doi: 10.1021/bc050029y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Synthetic DNA delivery systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis ME. Non-viral gene delivery systems. Curr. Op. Biotech. 2002;13:128–131. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabanov AV, Felgner PL, Seymour LW. Self-assembling complexes for gene delivery: From laboratory to clinical trial. New York: John Willey and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felgner PL. Particulate systems and polymers for in vitro and in vivo delivery of polynucleotides. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 1990;5:163–187. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Putnam D. Polymers for gene delivery across length scales. Nature Materials. 2006;5:439–451. doi: 10.1038/nmat1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reineke TM, Grinstaff MW. Designer materials for nucleic acid delivery. Mat. Res. Soc. Bull. 2005;30:635–639. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barthélémy P, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. Supramolecular assemblies with DNA. Pure App. Chem. 2005;77:2133–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pannier AK, Shea LD. Controlled release systems for DNA delivery. Molecular Therapy. 2004;10:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loakes D. Survey and summary : The applications of universal DNA base analogues. Nucleic Acid Res. 2001;29:2437–2447. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loakes D, Brown DM. 5-nitroindole as an universal base analogue. Nucleic Acid Res. 1994;29:4039–4034. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harki DA, Graci JD, Edathil JP, Castro C, Cameron CE, Peterson BR. Synthesis of a universal 5-nitroindole ribonucleotide and incorporation into RNA by a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1359–1362. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harki DA, Graci JD, Korneeva VS, Ghosh SKB, Hong Z, Cameron CE, Peterson BR. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of a mutagenic and non-hydrogen bonding ribonucleoside analogue: 1-beta-D-ribofuranosyl-3-nitropyrrole. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9026–9033. doi: 10.1021/bi026120w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart AO, Williams RM. C-glycosidation of pyridyl thioglycosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:4289–4296. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harusawa S, Imazu T, Takashima S, Araki L, Ohishi H, Kurihara T, Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Yamatodani AJ. Synthesis of 4(5)-[5-(aminomethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl- or 5-(aminomethyl)-2,5-dihydrofuran-2-yl]imidazoles by efficient use of a PHSe group: Application to novel histamine H3-ligands. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8608–8615. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bray BL, Mathies PH, Naef R, Solas DR, Tidwell TT, Artis DR, Muchowski JM. N-(triisopropylsilyl)pyrrole. A progenitor "par excellence" of 3-substituted pyrroles. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:6317–6328. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geall AJ, Blasgbrough IS. Rapid and sensitive ethidium bromide fluorescence quenching assay of polyamine conjugate-DNA interactions for the analysis of lipoplex formation in gene therapy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2000;22:849–859. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cain BF, Baguley BC, Demmy MW. Potential antitumor agents. 28. Deoxyribonucleic acid polyintercalating agents. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:658–668. doi: 10.1021/jm00205a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergstrom DE, Zhang P, Toma PH, Andrews PC, Nichols R. Synthesis, structure, and deoxyribonucleic-acid sequencing with a universal nucleoside -1-(2'-deoxy-beta-D-ribofuranosyl)-3-nitropyrrole. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1201–1209. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols R, Andrews PC, Zhang P, Bergstrom DE. A universal nucleoside for use at ambiguous sites in DNA primers. Nature. 1994;369:492–493. doi: 10.1038/369492a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behr JP. Synthetic gene-transfer vectors. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:274–278. doi: 10.1021/ar200213g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L, Hung M, Wagner E, editors. Nonviral vectors for gene therapy. Vol. 1999. New York: Academic Press; 1999. p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller AD. Cationic liposomes for gene therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. 1998;37:1768–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remy J, Sirlin C, Vierling P, Behr J. Gene transfer with a series of lipophilic DNA-binding molecules. Bioconj. Chem. 1994;5:647–654. doi: 10.1021/bc00030a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deshmukh HM, Huang L. Liposome and polylysine mediated gene transfer. New. J. Chem. 1997;21:113–124. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Legendre JY, Szoka FCJ. Delivery of plasmid DNA into mammalian cell lines using ph sensitive liposomes: Comparison with cationic liposomes. Pharm. Res. 1992;10:1235–1242. doi: 10.1023/a:1015836829670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacDonald RC, Ashley GW, Shida MM, Rakhmanova VA, Tarahovsky YS, Kennedy MT, Pozharski EV, Baker KA, Jones RD, Rosenzweig HS, Choi KL, Qiu R, McIntosh TJ. Physical and biological properties of cationic triesters of phosphatidylcholine. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2612–2629. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77095-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robbins PD, Tahara H, Ghivizzani SC. Viral vectors for gene therapy. Trends Biotech. 1998;16:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller AD. The problem with cationic liposome/micelle-based non-viral vector systems for gene therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1195–1211. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu YM, Wenning L, Lynch M, Reineke TM. New poly(D-glucaramidoamine)s induce DNA nanoparticle formation and efficient gene delivery into mammalian cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7422–7423. doi: 10.1021/ja049831l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Synthesis, characterization data, transfection studies, and cell cytotoxicity data. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.