Abstract

The Breast Cancer Metastasis Suppressor 1 (BRMS1) belongs to an expanding category of proteins called metastasis suppressors that demonstrate in vivo metastasis suppression while still allowing growth of the orthotopic tumor. Since BRMS1 decreases either the expression or function of multiple mediators implicated in resistance to chemotherapy (NF-κB, AKT, EGFR), we asked whether breast carcinoma cells expressing BRMS1 could be sensitized upon exposure to commonly used therapeutic agents that inhibit some of these same cellular mediators as BRMS1. In this report, we demonstrate that chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells is preserved in the presence of BRMS1. Further, BRMS1 does not change expression of AKT isoforms or PTEN, implicated in chemoresistance to common drug agents. Overall, our data with two different metastatic breast cancer cell lines indicates that BRMS1 expression status may not interfere with the response to commonly used chemotherapeutic agents in the management of solid tumors such as breast cancer. Since tumor protein expression analysis increasingly guides therapy decisions, our data may be of clinical benefit in disease management including profiling for BRMS1 expression before start of therapy.

Keywords: breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1), chemoresistance, 3D-culture, breast cancer, metastasis

Introduction

The Breast Cancer Metastasis Suppressor 1 (BRMS1) belongs to an expanding class of proteins called metastasis suppressors that demonstrate in vivo metastasis suppression while allowing growth of the orthotopic tumor [1–3]. BRMS1 functions as a metastasis suppressor in animal models of breast [4], melanoma [5], ovarian carcinomas [6]. Recent studies with clinical samples have indicated a correlation between loss of BRMS1 expression and poor prognosis in a subset of patients [7–9]. Experimentally, loss of metastasis suppressors, including BRMS1 may be reversed using therapeutic agents [10, 11] suggesting use of BRMS1 and other metastasis suppressors as markers and a potential adjuvant role of such “re-expression therapy” in the management of metastasis. Experimentally, BRMS1 expression increases susceptibility to anoikis which is proposed to contribute, in part, to metastasis suppression [12, 13]. BRMS1 is part of the Sin3-HDAC chromatin remodeling complexes [14, 15] that regulate gene expression and which could potentially alter chemotherapeutic responses [16]. Consequently, BRMS1 regulates expression of several signaling intermediates including epidermal growth factor receptor [17], osteopontin [18, 19], phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) [20], urokinase plasminogen activator [21], fascin [6], and connexins [22]. Further, BRMS1 regulates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activity [21] and AKT phosphorylation [17] in response to exogenous stimuli implicated in chemoresistance in a number of cancer models [23–25]. Recently, Rivera and colleagues suggested that BRMS1 expression may increase chemosensitivity as a consequence of downregulation of 14-3-3-γ, sorcin, and Hsp27 [26].

Taken together, since BRMS1 decreases either the expression or activity of multiple mediators implicated in resistance to chemotherapy (e.g. NF-κB, AKT, EGFR) and increases susceptibility to anoikis, we asked whether breast carcinoma cells expressing BRMS1 could respond differently upon exposure to commonly used therapeutic agents in the treatment of breast cancer. In this report, using multiple approaches we evaluated that chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells is preserved in the presence of BRMS1. Further, BRMS1 does not change expression of AKT isoforms or PTEN, implicated in chemoresistance to common drug agents. Information from these studies may be potentially used in the clinic in stratifying patients and designing treatment courses in the management of metastatic disease.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-435 breast adenocarcinoma cells [27] were transfected with a lentiviral vector construct expressing BRMS1 under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter [13]. MDA-MB-231/435 vector transfectants (231/435), and 231BRMS1/435BRMS1 were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s-modified essential medium (DMEM) and Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids, and L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and containing 5% fetal bovine serum (cDMEM-F12). 231 and 231BRMS1 cells were passaged using 0.125% trypsin and 2 mM EDTA solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 435 and 435BRMS1 cells were passaged using 2 mM EDTA in Ca2+/Mg2+- free PBS. Cell lines were confirmed to be free of Mycoplasma contamination using PCR (TaKaRa, Japan). No antibiotics or antimycotics were used.

Chemotherapeutic agents

Doxorubicin, vincristine were dissolved in water and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), paclitaxel were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Stock solutions of doxorubicin (10 mM), vincristine (1 mM) were stored at 4 C and 5-FU (500 mM), paclitaxel (1 mM) were stored at −20°C according to manufacturer’s instructions. For final drug concentrations, solutions were serially diluted in media and added to wells. The highest doses of doxorubicin, vincristine, 5-FU, and paclitaxel used for assays were 20 μM, 1 μM, 2000 μM and 1 μM respectively. All drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO and were used within one week of preparation.

Clonogenic assay

Cells (231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1) were passaged and allowed to proliferate to 70% confluence in 10 cm dishes for at least 2 passages to ensure log growth before harvesting for seeding. Cells were seeded in triplicate at a density of 1000 cells/well onto 6-well plates (Corning) in a final volume of 2 ml media and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, drugs were added at the indicated final concentrations in a volume of 2 ml media and incubated with cells for 4 h. Drug containing media was aspirated gently after 4 h and replaced with 5 ml fresh pre-warmed medium in each well [28]. Cells were left undisturbed in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 7 days and colonies formed were counted by staining with a 1:3 solution of acetic acid:methanol containing 0.01% crystal violet (Carnoy’s fixative). Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice independently.

MTT indirect assay for proliferation

Exponentially growing 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were plated at a density of 2500 cells/well in 24-well plates in quadruplicate and allowed to attach overnight. The next day, drugs were added at the indicated concentrations in a final volume of 500 μl and cells were exposed to drugs for 4 h. After 4 h, drug containing media was gently aspirated and replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium and cells were incubated undisturbed in a humidified incubator until the time of assay. Every second day beginning the day of drug addition, 3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the media in each well at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated with cells for 3 h. Following incubation with MTT, medium was aspirated gently and 500 μl of DMSO was added to each well and plates were shaken on a horizontal shaker for 30 minutes to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was read in a plate reader at 490 nm and experiments were repeated independently at least twice.

Chemosensitivity in 3D-culture

Exponentially growing 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/well on 8-well chamber slides (Nunc, Nalgene). Before plating cells, each well was coated with a Matrigel cushion (40 μl). The final concentration of Matrigel above the cushion layer was adjusted to 10%. Media containing cells (200 μl) was mixed with a 20% Matrigel suspension in cold media containing drug at 2X of the indicated concentrations (200 μl). The two suspensions were mixed together gently to ensure equal distribution of cells and drugs and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. Cells were incubated for nine days and colonies formed were counted. Experiments were repeated independently at least twice.

Immunoblotting

Cells grown to approximately 80% confluence on 100 mm dishes were rinsed 2X with ice-cold PBS cells and lysed in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM benzamidine, and protease inhibitor cocktail containing aprotinin, leupeptin, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford colorimetric assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein was denatured with Laemmli’s buffer at 95°C for 5 min and lysate equal to 50 μg total protein was loaded onto each well. Proteins were separated using either 8% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels and resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were incubated in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% fat-free dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies to AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, PTEN (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C and subsequently with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Gels were either run separately for each protein or membranes were stripped with stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and re-probed. Signals were visualized using ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) following manufacturer’s instructions. Blots were probed with an anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to confirm equal protein loading.

Results

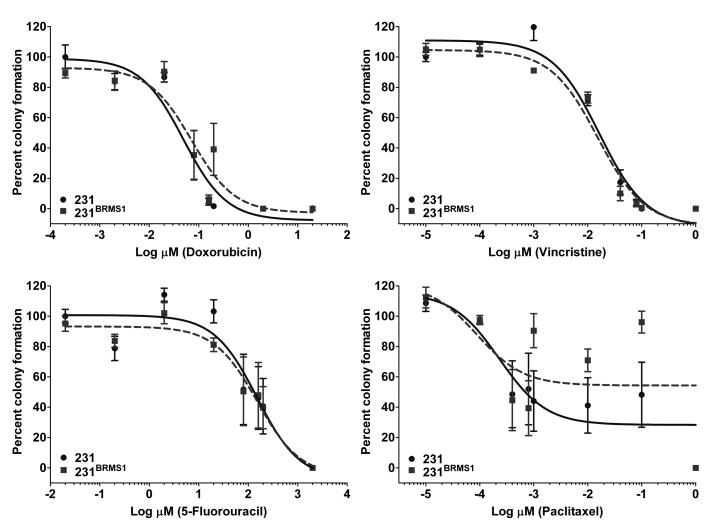

BRMS1 expression does not affect clonogenicity in response to chemotherapeutic agents

Clonogenic assays were used to determine dose-responses over a minimum of four log concentration range for each drug with 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells. IC50 values and corresponding confidence intervals were determined from the dose-response curves generated using Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) (Fig. 1, Table 1). A trend towards BRMS1-expressing cells forming fewer colonies was observed with most drugs in 231 as well as 435 cells, although statistical significance was not reached. IC50 values were similar in BRMS1-expressing vs. vector transfected cells (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

BRMS1 does not modify survival in clonogenic assays in response to chemotherapeutic agents. 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were plated at a density of 1000 cells/well of a 6-well plate and allowed to attach overnight. The next day, cells were exposed to drugs at the indicated concentrations for 4 h followed by replacement of drug containing medium with fresh medium. Cells were left undisturbed in a humidified incubator for 7 days at 37°C. At the assay end point, colonies formed were stained and counted. Similar dose-response curves were generated for 435/435BRMS1 cells (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of chemotherapeutic agents on clonogenicity of breast cancer cells expressing BRMS1

| IC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | 231 | 231BRMS1 | 435 | 435BRMS1 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.049 (0.027–0.086) | 0.071 (0.033–0.153) | 0.122 (0.078–0.190) | 0.114 (0.065–0.199) |

| Vincristine | 0.016 (0.010–0.025) | 0.015 (0.010–0.021) | 0.001 (0.0002–0.01) | 0.001 (4.4e-006–0.472) |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 150.2 (54.06–417.4) | 151.6 (56.10–409.5) | 663 (486.7–903.1) | 476.9 (142.3–1599) |

| Paclitaxel | 0.0002 (4.5e-005–0.001) | 8.81e-005 (6.9e-006–0.001) | 0.029 (0.011–0.074) | 0.012 (0.004 to 0.034) |

231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were seeded in triplicate at a density of 1000 cells/well in 6-well plates in a final volume of 2 ml media and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, drugs were added at the indicated final concentrations in a volume of 2 ml media and allowed contact with cells for 4 h. Drug containing media was aspirated after 4 h and replaced gently with 5 ml fresh pre-warmed medium in each well. Cells were left undisturbed in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 7 days and colonies formed were counted by staining with a 1:3 solution of acetic acid:methanol containing 0.01% crystal violet (Carnoy’s fixative). Cell clusters containing >50 cells were counted as colonies. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice independently. Numbers in parentheses represent 95% confidence interval values. IC50 values represent concentrations of drugs resulting in a 50% reduction in colony number.

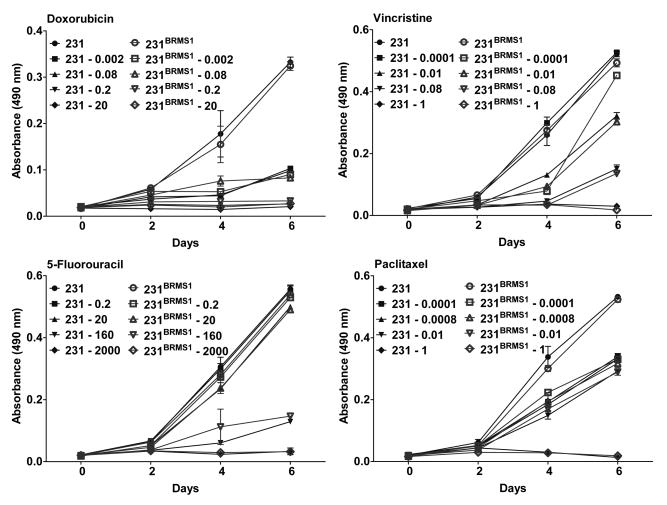

Expression of BRMS1 does not affect proliferation of breast cancer cells in the presence of chemotherapeutic agents

Consistent with previous results, expression of BRMS1 did not affect proliferation of either 231 or 435 cells [4, 13]. Addition of chemotherapeutic agents inhibited the proliferation of vector transfected cell lines in a dose-dependent manner as measured by MTT assays. Following exposure to chemotherapeutic agents, BRMS1 expressing cells showed a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation that paralleled decreases observed with the vector transfectants (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

BRMS1 does not change proliferation of breast cancer cells in response to chemotherapeutic agents. 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were plated at density of 2500 cells/well of 24-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, cells were exposed to drugs for 4 h and media was replaced with fresh medium. At each assay point, MTT was added to each well at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated for 3 h. Formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO and absorbance was recorded on a plate reader at 490 nm. Similar curves were generated for 435/435BRMS1 cells (data not shown).

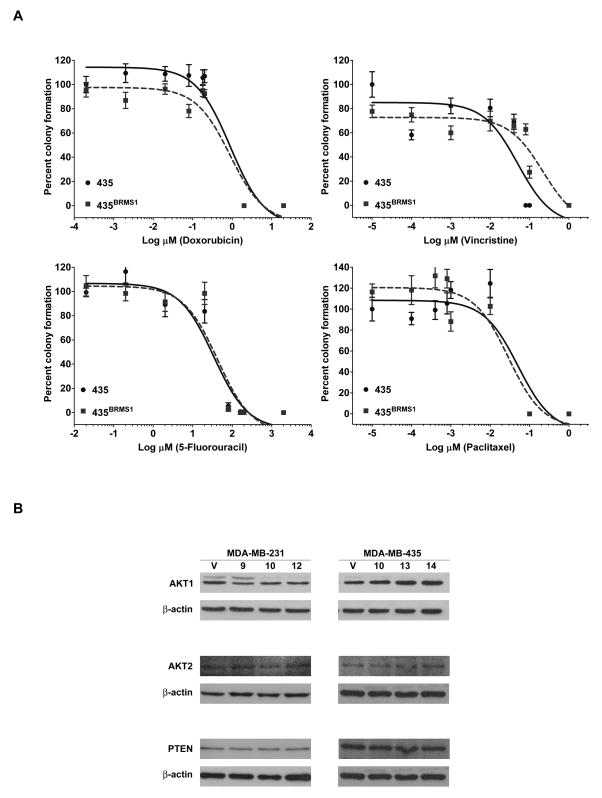

Breast cancer cells expressing BRMS1 are equally sensitive to chemotherapeutic agents in 3D-culture

Cells grown in 3D-culture exhibit distinct structural, behavioral phenotypes and drug responses compared to 2D-culture [29–31]. Further, responses to chemotherapy appear to be distinct in 2D- vs. 3D-culture [32]. Therefore, we tested whether the response of BRMS1- expressing cells to chemotherapeutic agents was modified under 3D-culture conditions. Consistent with observations that cells in 3D-culture display differential drug responses [29–31], IC50 values obtained were different from those obtained in clonogenic assays (Fig. 3A, Table 1, and Table 2). A dose-dependent decrease in colony formation was observed in 435 and 435BRMS1 cells. BRMS1-expressing cells tended to form fewer colonies in 3D-culture compared to 435 cells, however, the results were variable and IC50 differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3A, Table 2). Similar results were obtained with 231 and 231BRMS1 expressing cells (Table 2). Although not quantified, colony sizes between vector transfectants and BRMS1-expressing cells with or without addition of chemotherapeutic agents were also not appreciably different, although colony size decreased with increasing drug concentrations.

Figure 3.

BRMS1 maintains colony formation in 3D-culture, expression of AKT isoforms and PTEN. A) 435/435BRMS1 cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/well on 8-well chamber slides (Nunc, Nalgene) along with the indicated concentration of drugs in 10% Matrigel and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for seven days. After nine days, colonies formed were visualized under a light microscope and counted. Cell clusters visually identified as containing >50 cells were counted as colonies. Similar dose-response curves were generated for 231/231BRMS1 cells (data not shown). B) Cells lysates were obtained from 231, multiple 231BRMS1 clones (9, 10, 12) and 435, multiple 435BRMS1 clones (10, 13, 14) and immunoblotted for AKT isoforms and PTEN. β-actin was used as a loading control. No consistent changes in expression of AKT isoforms or PTEN were observed in BRMS1-expressing cells.

Table 2.

Effect of chemotherapeutic agents on colony formation of BRMS1-expressing breast cancer cells in 3D-culture

| IC50(μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | 231 | 231BRMS1 | 435 | 435BRMS1 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.277 (0.177–0.431) | 0.544 (0.333–0.891) | 0.895 (0.507–1.580) | 0.881(0.511–1.521) |

| Vincristine | 0.017 (0.010–0.027) | 0.032 (0.019–0.054) | 0.05 (0.026–0.096) | 0.22 (0.104–0.465) |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 43.35 (27.94–67.26) | 65.09 (41.81–101.3) | 33.97 (20.15–57.25) | 42.98 (25.27–73.11) |

| Paclitaxel | 0.028 (0.017–0.048) | 0.043 (0.023–0.079) | 0.051 (0.021–0.124) | 0.029 (0.013–0.063) |

Exponentially growing 231/231BRMS1 and 435/435BRMS1 cells were seeded at a density of 5000 cells/well on 8-well chamber slides (Nalgene) in 10% Matrigel. Media containing cells (200 μl) was mixed with a 20% Matrigel suspension in cold media containing drug at 2x of the indicated concentrations (200 μl). The two suspensions were mixed together gently to ensure equal distribution of cells and drugs and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. Cells were incubated for nine days and colonies formed were counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice independently. Numbers in parentheses represent 95% confidence interval values. IC50 values represent concentrations of drugs resulting in a 50% reduction in colony number.

BRMS1 does not change expression of AKT isoforms or PTEN

Since chemoresistance has been correlated with increased expression of AKT, expression of AKT isoforms in vector-transfected vs. BRMS1-expressing cells was tested by immunoblotting. Basal protein levels of AKT1 and AKT2 did not change significantly in BRMS1 expressing cells or changes were not consistent between cell lines (Fig. 3B). AKT3 was undetectable in either cell line or BRMS1-expressing cells. Since BRMS1-expressing cells have >95% lower levels of PtdIns(4,5)P2 [20], we also examined whether PTEN (catalyzes conversion of PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 to PtdIns(4,5)P2) expression was altered by BRMS1 expression. PTEN protein expression was unchanged in BRMS1 expressing cells.

Discussion

Innate or acquired chemoresistance to therapeutic agents remains a challenge in the management of cancer and especially metastasis. Multi-drug therapy is often targeted at the heterogeneous residual cancer cells, usually following surgical resection, with the hope of preventing recurrence. In addition to standard-of-care drugs, the choice of particular chemotherapeutics is often guided by histo- and/or expression analysis of various markers -dependent on cancer type [33]. Expression profiling of tumors before initial chemotherapy is becoming increasingly common and has aided in the development of targeted therapy including Herceptin® and Avastin®.

Histochemical analysis reveals that clinically, loss of BRMS1 is correlated with poor prognosis in a subset of breast carcinomas [7–9]. Further, BRMS1 expression is lost in higher grade ovarian [6] and supraglottic laryngeal carcinomas [34]. At the molecular level, increased AKT and NF-κB activity have been demonstrated to contribute to chemoresistance [23–25]. BRMS1 selectively decreases AKT phosphorylation in response to growth factors [17] and downregulates NF-κB activity [21]. Although we show here that BRMS1 does not modulate PTEN expression, PtdIns(4,5)P2 is decreased by >95% in BRMS1-expressing cells [20]. Since BRMS1 downregulates a number of mediators of chemoresistance, and since BRMS1 expression appears to be important in determining metastatic fate, these data provided a compelling rationale to test the hypothesis that BRMS1 would increase chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells. To our surprise, BRMS1 expression did not alter chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells in multiple in vitro assays.

Chemotherapeutic agents in this study were selected based on their known mechanisms of action, and their ability to antagonize or act through some of the same pathways mediated by BRMS1. For example, doxorubicin has been demonstrated to decrease levels of PtdIns(4,5)P2[35] while vincristine mediates cell death, in part, by activation of pro-apoptotic genes through NF-κB [36, 37]. Previous data indicates that BRMS1 expression did not alter in vitro proliferation or rate of in vivo tumor growth [4, 13, 38, 39]. Halogenated pyrimidines including 5-FU are metabolized to derivatives that replace thymidylate in actively dividing cells [40]. The anthracycline antibiotic doxorubicin (adriamycin) forms a trimer-complex with topoisomerase-II and DNA and also intercalates with DNA in dividing cells preventing DNA replication. The relative lack of effect of 5-FU and doxorubicin on both colony formation and proliferation of BRMS1-expressing cells may therefore be explained by the lack of change in proliferation rate by BRMS1 in vitro, although a comparable dose-dependent decrease in assay end-points is observed. Doxorubicin is also reported to decrease PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels [35] (as BRMS1 does), however, no potentiation of growth inhibition was observed when BRMS1-expressing cells were exposed to doxorubicin. The vinca alkaloid vincristine and the diterpenoid paclitaxel both bind β-tubulin and disrupt microtubule polymerization and disassembly respectively. BRMS1 has recently been shown to downregulate β-tubulin 6 (TUBB6) expression by microarray analysis [41]. In the presence of downregulation of TUBB6, BRMS1-expressing cells show no apparent disruption in cell-cycle progression (data not shown). Inhibition of NF-κB is known to sensitize tumor cells to microtubule disrupting agents such as paclitaxel and vincristine [42]. Reports also indicate that activation of NF-κB following vincristine exposure is perhaps required for inducing pro-apoptotic genes [36, 37]. The apparent lack of change in survival of BRMS1-expressing cells may reflect antagonistic signaling through NF-κB. Expression analysis of common mediators of chemoresistance including AKT isoforms and PTEN also did not show consistent changes in BRMS1-expressing cells suggesting that the lack of increased sensitivity to drugs tested may not involve these mediators.

Overall, our data with two different breast cancer cell lines indicates that BRMS1 expression status does not modify the response to commonly used chemotherapeutic agents although the mechanisms of actions of these drugs and BRMS1 intersect at various levels of signaling. Since tumor protein expression analysis increasingly guides therapy decisions, and since loss of BRMS1 is predictive of metastatic outcome [7], our data may be of translational benefit in directing the course of disease management including profiling for BRMS1 expression before start of therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US Public Health Service Grant (R01-CA87728) with additional support from the National Foundation for Cancer Research - Center for Metastasis Research (DRW). KSV was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (PDF1122006) from Susan G Komen For the Cure. JSS was supported by the Program for Research Experience in Pathology (P.R.E.P.) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. We thank members of the Welch laboratory for their helpful suggestions and discussion and Dr. Monica M. Richert for technical assistance with the 3D-culture system.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stafford LJ, Vaidya KS, Welch DR. Metastasis suppressors genes in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:874–891. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaidya KS, Welch DR. Metastasis suppressors and their roles in breast carcinoma. J Mamm Gland Biol Neopl. 2007;12:175–190. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles SA, Welch DR. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1742–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seraj MJ, Samant RS, Verderame MF, Welch DR. Functional evidence for a novel human breast carcinoma metastasis suppressor, BRMS1, encoded at chromosome 11q13. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2764–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shevde LA, Samant RS, Goldberg SF, Sikaneta T, Alessandrini A, Donahue HJ, Mauger DT, Welch DR. Suppression of human melanoma metastasis by the metastasis suppressor gene, BRMS1. Exp Cell Res. 2002;273:229–239. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S, Lin QD, Di W. Suppression of human ovarian carcinoma metastasis by the metastasis-suppressor gene, BRMS1. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:522–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks DG, Yoder BJ, Short S, Tarr S, Prescott N, Crowe JP, Dawson AE, Budd GT, Sizemore S, Cicek M, Choueiri T, Tubbs RR, Gaile D, Nowak N, Accavitti-Loper MA, Frost AR, Welch DR, Casey G. Loss of BRMS1 protein expression predicts reduced disease-free survival in hormone receptor negative and HER2 positive subsets of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6702–6708. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark AM, Tongers K, Maass N, Mehdorn HM, Held-Feindt J. Reduced metastasis-suppressor gene mRNA-expression in breast cancer brain metastases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;131:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z, Yamashita H, Toyama T, Yamamoto Y, Kawasoe T, Iwase H. Reduced expression of the breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 mRNA is correlated with poor progress in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6410–6414. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metge BJ, Frost AR, King JA, Dyess DL, Welch DR, Samant RS, Shevde LA. Epigenetic silencing contributes to the loss of BRMS1 expression in breast cancer. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 2008;25:753–763. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmieri D, Halverson DO, Ouatas T, Horak CE, Salerno M, Johnson J, Figg WD, Hollingshead M, Hursting S, Berrigan D, Steinberg SM, Merino MJ, Steeg PS. Medroxyprogesterone acetate elevation of Nm23-H1 metastasis suppressor expression in hormone receptor-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:632–642. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedley BD, Vaidya KS, Phadke P, MacKenzie L, Dales DW, Postenka CO, MacDonald IC, Chambers AF. BRMS1 suppresses breast cancer metastasis in multiple experimental models of metastasis by reducing solitary cell survival and inhibiting growth initiation. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 2008;25:727–740. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phadke PA, Vaidya KS, Nash KT, Hurst DR, Welch DR. BRMS1 suppresses breast cancer experimental metastasis to multiple organs by inhibiting several steps of the metastatic process. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:809–817. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meehan WJ, Samant RS, Hopper JE, Carrozza MJ, Shevde LA, Workman JL, Eckert KA, Verderame MF, Welch DR. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1) forms complexes with retinoblastoma-binding protein 1 (RBP1) and the mSin3 histone deacetylase complex and represses transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1562–1569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurst DR, Mehta A, Moore BP, Phadke PA, Meehan WJ, Accavitti MA, Shevde LA, Hopper JE, Xie Y, Welch DR, Samant RS. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1) is stabilized by the Hsp90 chaperone. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2006;348:1429–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida M, Furumai R, Nishiyama M, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Horinouchi S. Histone deacetylase as a new target for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48:S20–S26. doi: 10.1007/s002800100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaidya KS, Harihar S, Stafford LJ, Hurst DR, Hicks DG, Casey G, DeWald DB, Welch DR. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor-1 differentially modulates growth factor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28354–28360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710068200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedley BD, Welch DR, Allan AL, Al-Katib W, Dales DW, Postenka CO, Casey G, MacDonald IC, Chambers AF. Downregulation of osteopontin contributes to metastasis suppression by breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:526–534. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samant RS, Clark DW, Fillmore RA, Cicek M, Metge BJ, Chandramouli KH, Chambers AF, Casey G, Welch DR, Shevde LA. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1) inhibits osteopontin transcription by abrogating NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeWald DB, Torabinejad J, Samant RS, Johnston D, Erin N, Shope JC, Xie Y, Welch DR. Metastasis suppression by breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 involves reduction of phosphoinositide signaling in MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicek M, Fukuyama R, Welch DR, Sizemore N, Casey G. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 inhibits gene expression by targeting nuclear factor-κB activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3586–3595. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders MM, Seraj MJ, Li ZY, Zhou ZY, Winter CR, Welch DR, Donahue HJ. Breast cancer metastatic potential correlates with a breakdown in homospecific and heterospecific gap junctional intercellular communication. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1765–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng JQ, Lindsley CW, Cheng GZ, Yang H, Nicosia SV. The Akt/PKB pathway: molecular target for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2005;24:7482–7492. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham CG, Bubici C, Zazzeroni F, Knabb JR, Papa S, Kuntzen C, Franzoso G. Upregulation of Twist-1 by NF-kappaB blocks cytotoxicity induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Molec Cell Biol. 2007;27:3920–3935. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01219-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebens S, Arlt A, Schafer H. NF-kappaB as a molecular target in the therapy of pancreatic carcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2008;177:151–164. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71279-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivera J, Megias D, Bravo J. Proteomics-based strategy to delineate the molecular mechanisms of the metastasis suppressor gene BRMS1. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4006–4018. doi: 10.1021/pr0703167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cailleau R, Olive M, Cruciger QVJ. Long-term human breast carcinoma cell lines of metastatic origin: preliminary characterization. In Vitro. 1978;14:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF02616120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welch DR, Nicolson GL. Phenotypic drift and heterogeneity in response of metastatic mammary adenocarcinoma cell clones to Adriamycin, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine and methotrexate treatment in vitro. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 1983;1:317–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00121194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver VM, Fischer AH, Peterson OW, Bissell MJ. The importance of the microenvironment in breast cancer progression: Recapitulation of mammary tumorigenesis using a unique human mammary epithelial cell model and a three-dimensional culture assay. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:833–851. doi: 10.1139/o96-089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debnath J, Brugge JS. Modelling glandular epithelial cancers in three-dimensional cultures. Nature Rev Cancer. 2005;5:675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrc1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smalley KS, Lioni M, Herlyn M. Life isn’t flat: taking cancer biology to the next dimension. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2006;42:242–247. doi: 10.1290/0604027.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura T, Kato Y, Fuji H, Horiuchi T, Chiba Y, Tanaka K. E-cadherin-dependent intercellular adhesion enhances chemoresistance. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:693–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones SE. Metastatic breast cancer: the treatment challenge. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:224–233. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Guo X, Li F, Li X, Guan C, Yang H, Pan Z, Li C, Ren Z. Expression and clinical significance of breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 mRNA in supraglottic laryngeal carcinoma. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;22:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson MG, Chahwala SB, Hickman JA. Inhibition of human erythrocyte inositol lipid metabolism by adriamycin. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2799–2803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Fang Y, Dziadyk JM, Norris JS, Fan W. The possible correlation between activation of NF-kappaB/IkappaB pathway and the susceptibility of tumor cells to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Oncol Res. 2002;13:113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Fang Y, Wu J, Dziadyk JM, Zhu X, Sui M, Fan W. Regulation of Vinca alkaloid-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB/IkappaB pathway in human tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samant RS, Seraj MJ, Saunders MM, Sakamaki T, Shevde LA, Harms JF, Leonard TO, Goldberg SF, Budgeon LR, Meehan WJ, Winter CR, Christensen ND, Verderame MF, Donahue HJ, Welch DR. Analysis of mechanisms underlying BRMS1 suppression of metastasis. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 2001;18:683–693. doi: 10.1023/a:1013124725690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samant RS, Debies MT, Hurst DR, Moore BP, Shevde LA, Welch DR. Suppression of murine mammary carcinoma metastasis by the murine ortholog of breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (Brms1) Cancer Lett. 2006;235:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eidinoff ML, Knoll JE, Klein D. Effect of 5-fluorouracil on the incorporation of precursors into nucleic acid pyrimidines. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1957;71:274–275. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(57)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Champine PJ, Michaelson J, Weimer B, Welch DR, DeWald DB. Microarray analysis reveals potential mechanisms of BRMS1-mediated metastasis suppression. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 2007;24:551–565. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mabuchi S, Ohmichi M, Nishio Y, Hayasaka T, Kimura A, Ohta T, Kawagoe J, Takahashi K, Yada-Hashimoto N, Seino-Noda H, Sakata M, Motoyama T, Kurachi H, Testa JR, Tasaka K, Murata Y. Inhibition of inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB phosphorylation increases the efficacy of paclitaxel in in vitro and in vivo ovarian cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7645–7654. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]