Abstract

We conducted a 15-year retrospective cohort study to determine the prevalence of restrictive lung disease prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT), and to assess whether this was a risk factor for poor outcomes. 2545 patients were eligible for the analysis. Restrictive lung disease was defined as a total lung capacity (TLC) <80% of predicted normal. Chest x-rays and /or computed tomography scans were reviewed for all restricted patients to determine whether lung parenchymal abnormalities were unlikely or highly likely to cause restriction. Multivariate Cox-proportional hazard and sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the relationship between restriction and early respiratory failure and nonrelapse mortality. Restrictive lung disease was present in 194 subjects (7.6%) prior to transplantation. Among these cases, radiographically apparent abnormalities were unlikely to be the cause of the restriction in 149 (77%) subjects. In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the presence of pulmonary restriction was significantly associated with a 2-fold increase in risk for early respiratory failure and nonrelapse mortality, suggesting that these outcomes occurring in the absence of radiographically apparent abnormalities may be related to respiratory muscle weakness. These findings suggest that pulmonary restriction should be considered as a risk factor for poor outcomes after transplant.

Keywords: Pulmonary restriction, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, survival, mortality risk

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are routinely performed before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) as a screen for underlying respiratory abnormalities and to provide baseline lung function measurements for comparison when transplant-related pulmonary complications are suspected [1]. Several studies examining the predictive value of pretransplant PFTs for post-transplant complications have demonstrated that impaired lung function before transplant increases the risk for post-transplant pulmonary complications and mortality [2-14]. However, the majority of these previous studies primarily focused on the one-second forced expiratory volume (FEV1) [2, 12, 14] and the carbon monoxide (CO) diffusion capacity (DLCO) [10-12, 14] as a surrogate measure of pulmonary gas exchange, or the effect of specific physiologic patterns such as the effect of pretransplant airflow obstruction on post-transplant outcomes [3, 4, 9, 12]. Although a few studies have evaluated the relationship between pretransplant pulmonary restriction and post-transplant outcomes [2, 12, 15], the prevalence of restrictive lung disease prior to allogeneic HCT and their influence on transplant outcomes is not well described.

There are multiple factors that can result in a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing prior to stem cell transplantation. These include advanced intrathoracic malignant lesions, spinal cord compression, prior treatments such as chemotherapy, thoracic surgery, thoracic radiation, or prior chronic respiratory disease or infection, and/or myopathies/deconditioning resulting in respiratory muscle weakness [1]. In a recent study, we found evidence that a reduced total lung capacity (TLC) prior to allogeneic HCT, which defines pulmonary restriction, may influence post-transplant outcomes [8]. These preliminary data and the current gap in knowledge regarding restrictive pulmonary processes and allogeneic HCT outcomes prompted us to conduct a 15-year retrospective cohort study to determine the prevalence of restrictive lung disease prior to allogeneic HCT, and assess whether this is a pretransplant risk factor for two major transplantation outcomes: early respiratory failure and nonrelapse mortality.

METHODS

Patient Selection

All patients who had their first allogeneic HCT at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (the “Center”) between July 6, 1992, and July 6, 2005, were eligible for this analysis (n = 2847). Patients who were younger than 15 years (n = 170), or without a pretransplant assessment of pulmonary static lung volumes (n = 132) were excluded. A total of 2545 patients were included in the final analyses.

Clinical Data

All clinical data were prospectively collected and retrospectively reviewed. The patient’s underlying disease state was categorized as low, intermediate, or high risk as previously described [8, 16]. Donor match status was determined according to donor-recipient ABO compatibility and HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR status. Stem cell sources were classified as bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cell, or other, which included cord blood, or a combination of bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell. Conditioning regimens were classified as reduced intensity or myeloablative. Patients in the myeloablative conditioning group included patients that received either a TBI- or non-TBI-based regimen. Patients in the reduced intensity conditioning group received 2 Gy of total body irradiation (TBI). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight and height and categorized as underweight (BMI<18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) and obese (BMI >30.0) [17].

Pulmonary function testing

According to standard transplant protocol at our Center, all patients underwent pulmonary function testing prior to transplantation when possible. The PFT obtained prior to and closest to the time of transplantation was used in the analysis. Among patients who received a bronchodilator challenge, the prebronchodilator values were used in this analysis. All PFTs were performed at our Center according to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines [18] using the Sensormedics 2100 (Sensormedics Co., Yorba Linda, CA) from July 1991 to August 1999, and the Sensormedics V-Max 22 with Autobox 6200 (Sensormedics Co.) from September 1999 to July 2005. Published equations for adults were used to determine predicted values of FEV1, FVC, total lung capacity (TLC), residual volume (RV), and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO)[18-20]. All diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurements were corrected for the hemoglobin measurement obtained closest to the time the diffusion capacity was measured, but not alveolar volume [21].

Chest imaging

Chest imaging data was reviewed for all patients determined to have pretransplant restrictive lung disease by PFT. Data were obtained by reviewing radiograph and chests computed tomography (CT) reports when available, and from reviewing clinical notes when imaging reports were not available. Imaging was obtained within 30 days before or after stem cell transplantation in most patients (96%). When both chest x-ray and chest CT results were available within the same time window, CT results were used preferentially. All reports were independently and collectively reviewed by three pulmonologists and classified as having a high or low probability that parenchymal lung disease or chest wall deformities were contributing significantly to the restrictive lung disease. Nodules, lobar infiltrates, cavities less than 4 cm, and small effusions were classified as low probability. Evidence of thoracic surgery, elevated diaphragm, diffuse interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, central masses, and moderate to severe pleural effusions were classified as high probability.

Restrictive pulmonary disease definitions

Restrictive lung disease was defined according to ATS/European Respiratory Society (ERS) criteria, defined as a TLC<80% [20, 22]. In order to examine whether respiratory muscle weakness may be associated with the outcomes, we performed a sensitivity analysis using two additional definitions of restrictive lung disease. The first definition required both TLC<80% and a FEV1/FVC ratio >0.7. The second alternative definition required the same, and also required a low probability chest image, one that provided no evidence for a parenchymal explanation for a restrictive pattern.

Outcome definitions

Patients were defined as having developed early respiratory failure if they required >24h hours of mechanical ventilation for a nonelective reason within the first 120 days after transplantation. Nonrelapse mortality was defined as mortality that occurred in patients who did not experience relapse of their underlying malignancy within the follow-up period.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows® (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois) and Stata/IC 10.0 for Windows® (StataCorp LP College Station, Texas). Two sided p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Diagnosis, disease status, and disease risk were evaluated as categorical variables. Pulmonary function parameters were evaluated as both continuous and categorical variables. Body mass index was considered as a categorical and continuous variable. Pearson χ2 test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. To evaluate if respiratory muscle weakness might be associated with worse outcomes, we performed a sensitivity analysis using three successively more stringent definitions for a restrictive pattern that is likely caused by respiratory muscle weakness. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the relationship between pulmonary restriction and the outcomes of interest. Patients who developed disease relapse were censored at the time of relapse for the nonrelapse mortality analysis. To account for potential changes in clinical practice over time, we considered the year of transplant as a categorical variable in the analysis. The incidence of developing early respiratory failure and nonrelapse mortality according to lung function parameters were plotted using cumulative incidence curves, with disease relapse treated as a competing event for nonrelapse mortality and all cause mortality treated as a competing event for respiratory failure. Cumulative incidence curves were compared using the methods of Gray [25].

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics and baseline lung function

The pretransplant clinical characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean (± standard deviation) number of days between PFTs and transplantation was 24 ± 9 days. Restrictive lung disease, defined by TLC <80%, was present in 194 (7.6%) patients (Table 2). The presence of restrictive lung disease increased as disease risk increased (p < 0.001; Table 3). Four percent of low risk patients had restrictive lung disease. This increased to 7% and 12% for patients with intermediate and high risk diseases, respectively. One hundred and seven chest CXR and 81 chest CTs were reviewed for the 194 patients with a restrictive pattern. Six patients did not have any radiographic images available for review. The majority of patients with a TLC < 80% had normal or near normal chest radiographic studies (n = 149; 77%) and were categorized as having a “low likelihood” of having parenchymal lung disease or a chest wall deformity as a cause of the pulmonary restriction. The remainder of patients with a TLC < 80% (n = 39; 20%) had prior thoracic surgery or radiographic evidence of mediastinal, lung or pleural abnormalities and were classified as having a “high likelihood” that parenchymal lung disease or chest wall deformities were a significant cause of the abnormal TLC. Patients with the most severely decreased TLC were more likely to have abnormal chest imaging (31% vs. 5%, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Patient pretransplant characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 2545 (100) |

| Age at transplant | 42 yrs. ± 12.3 |

| Race (White) | 2141 (84.1) |

| Sex (males) | 1487 (58.4) |

| Donor type | |

| HLA-matched related | 1690 (66.4) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 565 (22.2) |

| Unrelated | 237 (9.3) |

| Conditioning regimens | |

| Myeloablative | 2338 (92) |

| Nonmyeloablative | 207 (8) |

SD=standard deviation

Table 2. Distribution of pulmonary function parameters and chest imaging findings according to pretransplant total lung capacity categories.

| Pretransplant Total Lung Capacity Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥80% | 70-79% | 60-69% | <60% | p-value** | |

| Number of patients (%) | 2351 (92.4) | 134 (5.3) | 39 (1.5) | 21 (0.8) | |

| Mean body mass index (± SD) | 27 ± 5 | 28 ± 6 | 26 ± 5 | 23 ± 4 | 0.010 |

| Mean percent of predicted (± SD) | |||||

| FEV1 | 94 ±13 | 74 ± 9 | 61 ± 11 | 53 ± 20 | <0.0001 |

| FVC | 100 ±13 | 75 ± 9 | 63 ± 12 | 55 ± 21 | <0.0001 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| RV | 100 ± 26 | 76 ± 17 | 76 ± 19 | 76 ±28 | <0.0001 |

| DLCO | 90 ±17 | 74 ±20 | 62 ±13 | 54 ±16 | <0.0001 |

| Chest Radiographic Findings* | |||||

| Low probability | NA | 113 (76) | 29 (19) | 7 (5) | <0.0001 |

| High probability | NA | 18 (46) | 9 (23) | 12 (31) | <0.0001 |

Six patients did not have radiologic data available for review.

Pearson χ2 test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively

SD=standard deviation; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC=forced vital capacity; RV=residual volume; DLCO =carbon monoxide diffusion capacity

Table 3. Distribution of diagnosis, disease status, and disease risk according to pretransplant total lung capacity categories.

| Pretransplant TLC categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ≥80% n (%) |

70-80% n (%) |

60-70% n (%) |

<60% n (%) |

p-value* | |

| Diagnosis | <0.001 | |||||

| CML | 810 | 770 (95) | 30 (4) | 8 (1) | 2 (<1) | |

| ANL | 747 | 695 (93) | 39 (5) | 10 (1) | 3 (<1) | |

| MDS | 446 | 410 (92) | 24 (5) | 9 (2) | 3 (<1) | |

| ALL | 261 | 230 (88) | 21 (8) | 7 (3) | 3 (1) | |

| NHL | 147 | 129 (88) | 7 (5) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | |

| MM | 64 | 55 (86) | 5 (8) | 2 (8) | 2 (3) | |

| CLL | 50 | 46 (92) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| HD | 25 | 15 (60) | 6 (24) | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | |

| Disease status | <0.001 | |||||

| Accelerated phase | 139 | 132 (95) | 5 (4) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Blast crisis | 92 | 80 (87) | 8 (9) | 3 (3) | 1 (<1) | |

| Chronic phase | 581 | 560 (96) | 17 (3) | 4 (<1) | 0 (0) | |

| De novo | 34 | 30 (88) | 1 (2) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Relapse | 607 | 534 (88) | 47 (8) | 11 (2) | 15 (2) | |

| Remission | 591 | 555 (94) | 27 (5) | 8 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Unknown | 43 | 39 (91) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Others | 459 | 420 (92) | 27 (6) | 9(2) | 3 (<1) | |

| Disease risk | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 724 | 693 (96) | 23 (3) | 8 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Intermediate | 995 | 926 (93) | 50 (5) | 15 (1) | 4 (<1) | |

| High | 808 | 715 (88) | 61 (8) | 15 (2) | 17 (2) | |

Pearson χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables

CML=chronic myelogenous leukemia; AML=acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS=myelodysplastic syndrome; ALL=acute lymphocytic leukemia; NHL=non-Hodgkins lymphoma; MM=multiple myeloma; CLL=chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HD=Hodgkin’s disease

Among pretransplant characteristics, only disease diagnosis and stage were significantly associated with a TLC<80% (Table 3). Although the majority of the patients were in the highest TLC category, a larger percentage of the patients with Hodgkin’s disease had a pretransplant TLC in the lower categories (p < 0.001). Similarly, there was also a significant association between the baseline TLC and disease status at transplant (p < 0.001). To facilitate further analysis, we integrated the pretransplant diagnosis and disease status into a composite variable, disease risk, and confirmed the association with pretransplant TLC (Table 3). Since physiologic deconditioning or pulmonary injury from significant pre-treatment can result in a restrictive pattern and influence the risk of developing the outcomes, disease risk represents a potential confounding variable. Due to the low number of patients in each TLC category below 80%, we also dichotomized the TLC categories into ≥80% versus <80% for the remaining analyses.

Pretransplant restrictive lung disease and early respiratory failure

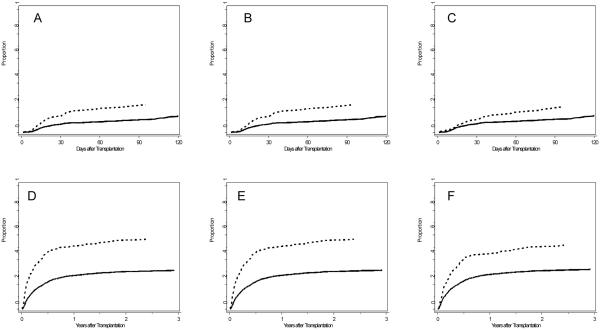

Pretransplant restrictive lung disease was significantly associated with a higher risk for early respiratory failure (hazard ratio [HR] 2.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.60-3.07, p<0.001) (Table 4). Cumulative incidence of early respiratory failure was significantly different between subjects with and without pretransplant TLC < 80% (p < 0.0001, Figure 1A). In an attempt to isolate the effect of respiratory muscle weakness we repeated this analysis using progressively stringent criteria for restrictive lung disease. When restrictive lung disease was defined as both a TLC<80% and FEV1/FVC ratio>0.7, it remained significantly associated with a two-fold increase in risk for early respiratory failure (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.57-3.06, p < 0.001). Using these criteria for pulmonary restriction, cumulative incidence of early respiratory failure remained significantly different between subjects with and without pretransplant pulmonary restriction (p < 0.0001, Figure 1B). The third analysis required a TLC<80%, FEV1/FVC ratio >0.7, and a low probability chest radiograph. Although attenuated slightly, a restrictive pattern remained significantly associated with an increase in risk for early respiratory failure (HR 1.84 95% CI 1.25-2.71, p < 0.002). Under this definition of pulmonary restriction, subjects with and without still had significantly different cumulative incidence of early respiratory failure (p = 0.012, Figure 1C).

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis of the association between pretransplant restriction and early respiratory failure.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Events | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| TLC<80% | ||||||

| No | 2351 (92) | 261 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 194 (8) | 43 | 2.22 (1.60 - 3.07) | <0.001 | 1.90 (1.36 - 2.65) | <0.001 |

| TLC<80%+FEV1/FVC >0.7 | ||||||

| No | 2358 (93) | 263 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 185 (7) | 41 | 2.19 (1.57 - 3.06) | <0.001 | 1.90 (1.35 - 2.66) | <0.001 |

| TLC<80%+FEV1/FVC >0.7+low probability on chest imaging | ||||||

| No | 2396 (93) | 275 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 143 (6) | 28 | 1.84 (1.25 - 2.71) | 0.002 | 1.59 (1.07 - 2.37) | 0.022 |

Adjusted for disease risk and year

TLC=total lung capacity; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC=forced vital capacity; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves for early respiratory failure (A, B, C) and nonrelapse mortality (E, F, G). Dotted lines indicate patients with pretransplant pulmonary restriction, solid lines indicate patients without pretransplant pulmonary restriction. Three definitions of pretransplant pulmonary restriction were used: TLC<80% alone (Figures A and D), TLC<80% and FEV1/FVC ratio >0.7 (Figures B and E), TLC<80%, FEV1/FVC ratio >0.7, and a low probability chest radiograph (Figures C and F). Gray’s test indicates significant differences between subjects with and without pulmonary restriction in cumulative incidence of early respiratory failure (A: p < 0.000, B: p < 0.0001, C: p = 0.012) and cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality (D: p < 0.0001, E: p < 0.0001, F: p < 0.0001).

Given the potential confounding effects of disease risk, we repeated these analyses after adjusting for disease risk in the models. We also adjusted for year of transplantation to account for any changes in clinical practice over the duration of this study. These adjustments reduced the point estimates. However, the associations between pulmonary restriction and early respiratory failure remained statistically significant for the first two definitions, and a trend toward significance with a smaller effect size remained for the third definition (Table 4).

Due to fundamental differences in patient characteristics among patients who receive a myeloablative versus a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, we also stratified the adjusted analysis based upon this criterion. Among patients who received a myeloablative conditioning regimen (N = 2338), presence of pretransplant pulmonary restriction remained significantly associated with increased risk for early respiratory failure in adjusted analysis (Definition 1: HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.43-1.95, p<0.001; Definition 2: HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.43-1.96, p<0.001; Definition 3: HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.44-1.98, p < 0.001). Among patients who received a reduced intensity conditioning regimen (N = 207), the presence of pretransplant pulmonary restriction according to the first two definitions was associated with a higher risk for early respiratory failure. This was no longer statistically significant in adjusted analyses (Definition 1: HR 2.81, 95% CI 0.73-10.82, p = 0.134; Definition 2: HR 1.80, 95% CI 0.38-8.46, p = 0.455). There were not enough cases with Definition 3 to perform an informative analysis.

Pretransplant restrictive lung disease and nonrelapse mortality

Restrictive lung disease was also significantly associated with a higher risk for nonrelapse mortality (HR 2.41, 95% CI 1.98-2.94, p < 0.001, Table 5). Sensitivity analyses using the two alternative definitions revealed that the association remained significant. According to the second alternative definition, presence of a restrictive pattern was associated with a two-fold increase in risk for nonrelapse mortality (HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.95-2.92, p < 0.001). According to the third alternative criteria, presence of a restrictive pattern was still significantly associated with a two-fold increase in risk of nonrelapse mortality (HR 1.98 95% CI 1.57-2.50, p < 0.001). Using each of these three criteria for pulmonary restriction, cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality was significantly different between subjects with and without pulmonary restriction (p < 0.0001, Figure 1D, 1E and 1F).

Table 5. Sensitivity analysis of the association between pretransplant restriction and nonrelapse mortality.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Events | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| TLC<80% | ||||||

| No | 2351 (92) | 261 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 194 (8) | 43 | 2.41 (1.98 - 2.94) | <0.001 | 2.18 (1.79 - 2.65) | <0.001 |

| TLC<80%+FEV1/FVC >0.7 | ||||||

| No | 2358 (93) | 263 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 185 (7) | 41 | 2.39 (1.95 - 2.92) | <0.001 | 2.18 (1.78 - 2.66) | <0.001 |

| TLC<80%+FEV1/FVC >0.7+low probability on chest imaging | ||||||

| No | 2396 (93) | 275 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 143 (6) | 28 | 1.98 (1.57 - 2.50) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.44 - 2.30) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for disease risk and year

TLC=total lung capacity; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC=forced vital capacity; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval

We also repeated these analyses after adjusting for disease risk and year of transplant in the models. The resultant point estimates decreased slightly, but the associations between pulmonary restriction and nonrelapse mortality remained statistically significant for all three definitions of pulmonary restriction (Table 4). We also performed stratified analyses of the adjusted models based upon conditioning regimen. Among patients who received a myeloablative conditioning regimen, presence of pretransplant pulmonary restriction remained significantly associated with increased risk for nonrelapse mortality (Definition 1: HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.68-2.56, p < 0.001; Definition 2: HR 2.10, 95% CI 1.70-2.60, p<0.001; Definition 3: HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.37-2.22, p < 0.001). Among patients who received a reduced intensity conditioning regimen, the association with nonrelapse mortality was neither consistent nor statistically significant with each definition for pretransplant pulmonary restriction (Definition 1: HR 1.69, 95% CI 0.86-3.32, p = 0.125; Definition 2: HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.55-2.56, p = 0.669; Definition 3: HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.17-2.04, p = 0.404).

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of pulmonary function serves as an important method for risk stratification of patients who are considering allogeneic HCT [7, 8, 10, 23-25]. The most recent studies clearly indicate that the presence of poor lung function prior to stem cell transplantation is associated with worse outcomes, including respiratory failure and mortality [7, 24]. However, these studies, and many others, are limited in their ability to comment on the potential biologic reasons by which poor lung function might influence a patient’s post transplant clinical course. There are two potential explanations for these repeated observations in the literature. First, impaired lung function likely leaves a patient with less pulmonary reserve, which means there is decreased lung capacity for surviving a period of critical illness. Second, prior lung injury may have immunologically primed the lungs, predisposing the lungs to additional immunologic injury during the transplantation process. However, based upon the observations of our current analysis, we suspect that there is a third explanation that may be linked to pulmonary restriction and respiratory muscle weakness.

Pretransplant pulmonary restriction is a significant clinical problem. In the current study, we found that the prevalence of pulmonary restriction among transplant candidates was only 8%, which is much lower than a previously reported observation of 29% in a study of patients transplanted between 1984 and 1990, an entirely different era of stem cell transplantation [2, 12, 15]. Given the observations associated with our most stringent definition of pulmonary restriction, we suspect that the majority of these patients with pulmonary restriction (77%) likely had evidence of respiratory muscle weakness prior to transplantation. This is supported by two observations. First, there was a direct correlation between BMI and TLC values; patients with lower BMI, who may be more likely to be physiologically deconditioned due to poor nutritional status, had lower TLC measurements. Second, there was also a significant relationship between disease type/risk and the degree of TLC reduction. While this could indicate that patients with the most advanced disease were more likely to have had thoracic or pulmonary injury resulting in pulmonary restriction, patients who had radiographic evidence of parenchymal or thoracic abnormalities that could cause restrictive lung disease were in the minority. Instead, we believe it is more likely that this group of patients were most likely to be physiologically deconditioned due to multiple previous rounds of aggressive cancer treatment. Based upon these observations, our results go beyond confirming that the presence of pulmonary restriction prior to transplantation was associated with a higher risk for respiratory failure and nonrelapse associated mortality. Our study provides the first published evidence that pretransplant pulmonary restriction may be caused by respiratory muscle weakness. This may partially explain the well-established relationship between poor lung function and worse allogeneic HCT outcomes.

Our analysis accounted for the major variables that might influence pulmonary function. First, as clearly demonstrated by the significant relationship between disease risk and pretransplant pulmonary restriction, we included disease risk as a potential confounding variable. While this inclusion did attenuate the magnitude of the effect associated with pretransplant pulmonary restriction, we demonstrated that despite this adjustment, this relationship with the two outcomes remained statistically significant. Second, we also accounted for potential changes in patient selection over the course of this 14-year period by including the year of transplant in our models. Again, this did not significantly influence our results, suggesting that this relationship is durable despite temporal changes related to transplant procedures and patient selection. Third, recognizing the potential physiologic differences of patient populations receiving myeloablative versus reduced intensity conditioning regimens, we stratified our analyses accordingly and found that while the association remained strong among patients who received a myeloablative regimen, this was less so for those that received a reduced intensity regimen. Nevertheless, we note that at least for the respiratory failure endpoint, the point estimates for the reduced intensity patients were similar in magnitude to that observed among the myeloablative patients. Our cohort may have been underpowered to demonstrate statistical significance for reduced intensity patients with respect to mortality.

Our study is subject to the usual limitations associated with single center retrospective studies. In addition, perhaps the most noteworthy limitation of our study is the lack of data from direct measurements of respiratory muscle strength with tools such as maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures, or even indirectly with grip strength. We were only able to infer that a restrictive pattern noted on PFTs, in the absence of any radiographic features that may explain the restrictive pattern, was most likely attributable to respiratory muscle weakness. However, respiratory muscle dysfunction is often present before pulmonary restriction is apparent on PFTs [26-28], suggesting that we have most likely underestimated the prevalence of respiratory muscle dysfunction. Although data for respiratory muscle strength are not available in our database, we believe such measurements could contribute significantly to not only our understanding of this process, but also help to direct clinical care with interventions that can increase respiratory muscle strength. In the future, prospective studies should consider incorporating relatively simple tools for measuring respiratory muscle function (e.g. maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures), which are available through most pulmonary function testing laboratories, to evaluate patients with and without a pretransplant TLC <80%.

In summary, the results from the current study demonstrate that pretransplant restrictive lung disease was a risk factor for allogeneic HCT outcomes and that it may possibly be attributable to respiratory muscle weakness. This may partially explain the higher risk for poor transplant outcome that has long been observed to be associated with poor pretransplant lung function. If confirmed, future studies should consider evaluating interventions that strengthen respiratory muscles to determine whether such measures can improve the outcomes of allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by: ISCIII BA06/90061, Red RESPIRA (RTIC-C03/11, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain), ARMAR, ERESMUS in COPD (BMTH4-CT98-3406, E.U.), and CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias, NIH grant HL088201.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this work were presented at the American Thoracic Society Annual Congress, Toronto 2008 and the Bone Marrow Transplant Tandem Meeting, San Diego, CA, February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chien JW, Madtes DK, Clark JG. Pulmonary function testing prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35(5):429–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghalie R, Szidon JP, Thompson L, Nawas YN, Dolce A, Kaizer H. Evaluation of pulmonary complications after bone marrow transplantation: the role of pretransplant pulmonary function tests. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992;10(4):359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien JW, Martin PJ, Gooley TA, Flowers ME, Heckbert SR, Nichols WG, et al. Airflow obstruction after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(2):208–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1468OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien JW, Martin PJ, Flowers ME, Nichols WG, Clark JG. Implications of early airflow decline after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33(7):759–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horak DA, Schmidt GM, Zaia JA, Niland JC, Ahn C, Forman SJ. Pretransplant pulmonary function predicts cytomegalovirus-associated interstitial pneumonia following bone marrow transplantation. Chest. 1992;102(5):1484–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.5.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho VT, Weller E, Lee SJ, Alyea EP, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ. Prognostic factors for early severe pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7(4):223–9. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11349809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parimon T, Au DH, Martin PJ, Chien JW. A risk score for mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(6):407–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parimon T, Madtes DK, Au DH, Clark JG, Chien JW. Pretransplant lung function, respiratory failure, and mortality after stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(3):384–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-212OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark JG, Schwartz DA, Flournoy N, Sullivan KM, Crawford SW, Thomas ED. Risk factors for airflow obstruction in recipients of bone marrow transplants. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(5):648–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford SW, Fisher L. Predictive value of pulmonary function tests before marrow transplantation. Chest. 1992;101(5):1257–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matute-Bello G, McDonald GD, Hinds MS, Schoch HG, Crawford SW. Association of pulmonary function testing abnormalities and severe veno-occlusive disease of the liver after marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21(11):1125–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarer AP, Hughes JM, Trotman-Dickenson B, Krausz T, Goldman JM. A chronic pulmonary syndrome associated with graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1992;54(6):1002–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gore EM, Lawton CA, Ash RC, Lipchik RJ. Pulmonary function changes in long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg SL, Klumpp TR, Magdalinski AJ, Mangan KF. Value of the pretransplant evaluation in predicting toxic day-100 mortality among blood stem-cell and bone marrow transplant recipients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(12):3796–802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badier M, Guillot C, Delpierre S, Vanuxem P, Blaise D, Maraninchi D. Pulmonary function changes 100 days and one year after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;12(5):457–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koc S, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, Anasetti C, Deeg HJ, Nash RA, et al. Therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a randomized trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone versus prednisone alone. Blood. 2002;100(1):48–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Report of a WHO Expert Committee Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Thoracic Society Single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (transfer factor). Recommendations for a standard technique--1995 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):2185–98. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123(6):659–64. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–68. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crapo RO, Morris AH. Standardized single breath normal values for carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123(2):185–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Thoracic Society Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(5):1202–18. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorror ML, Giralt S, Sandmaier BM, De Lima M, Shahjahan M, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation specific comorbidity index as an outcome predictor for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: combined FHCRC and MDACC experiences. Blood. 2007;110(13):4606–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, Maris MB, Baron F, Maloney DG, et al. Comorbidity and disease status based risk stratification of outcomes among patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplasia receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):4246–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochester DF, Esau SA. Assessment of ventilatory function in patients with neuromuscular disease. Clin Chest Med. 1994;15(4):751–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nava S. Monitoring respiratory muscles. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1998;53(6):640–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ATS/ERS Statement on respiratory muscle testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(4):518–624. doi: 10.1164/rccm.166.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]