Abstract

PURPOSE

To evaluate the risk of and risk factors for hypopyon among patients with uveitis, and to evaluate the risk of visual changes and structural complications following hypopyon.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

Patients with uveitis at four academic ocular inflammation subspecialty practices.

METHODS

Data were ascertained by standardized chart review.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Prevalence and incidence of hypopyon, risk factors for hypopyon, and incidence of visual acuity changes and of structural ocular complications following hypopyon.

RESULTS

Among 4,911 patients with uveitis, 41 (8.3/1000) cases of hypopyon were identified at the time of cohort entry. Of these, 2,885 initially free of hypopyon were followed over 9,451 person-years, during which 81 (2.8%) developed hypopyon (8.57/1000 person-years). Risk factors for incident hypopyon included Behçet’s disease (adjusted relative risk (RR)=5.30, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.76–10.2), diagnosis of a spondyloarthropathy (adjusted RR=2.86, 95% CI: 1.48–5.52), and HLA-B27 positivity (adjusted RR=2.04, 95% CI: 1.17–3.56). Patients with both a spondyloarthropathy and HLA-B27 tended to have higher risk than either factor alone (crude RR=4.39, 95% CI: 2.26–8.51). Diagnosis of intermediate uveitis (+/− anterior uveitis) was associated with a lower risk of hypopyon (with respect to anterior uveitis only, adjusted RR=0.35, 95% CI: 0.15–0.85). Hypopyon incidence tended to be lower among patients with sarcoidosis (crude RR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.06–0.90; adjusted RR=−0.28, 95% CI: 0.07–1.15). Post-hypopyon eyes and eyes not developing hypopyon had a similar incidence of band keratopathy, posterior synechiae, ocular hypertension, hypotony, macular edema, epiretinal membrane, cataract surgery, or glaucoma surgery. Post-hypopyon eyes were more likely than eyes which not developing hypopyon to gain 3 lines of vision (crude RR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.05–2.24) and were less likely to develop 20/200 or worse visual acuity (crude RR=0.41, 95% CI: 0.17–0.99); otherwise visual outcomes were similar in these groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Hypopyon is an uncommon occurrence in patients with uveitis. Risk factors included Behçet’s disease, HLA-B27 positivity, and diagnosis of a spondyloarthropathy. Intermediate uveitis cases (+/− anterior uveitis) had lower risk of hypopyon than other forms of uveitis. On average, post-hypopyon eyes were no more likely than other eyes with uveitis to develop structural ocular complications or lose visual acuity.

Hypopyon—layering of white blood cells in the anterior chamber—signifies severe anterior segment intraocular inflammation. The frequency of hypopyon has been described in two small to moderate-sized series of patients with various types of uveitis. D’Alessandro et al retrospectively reviewed 155 cases of acute anterior uveitis and found 11 (7%) cases of hypopyon (duration of follow-up not reported), 9 of which were associated with HLA-B27.1 BenEzra et al reviewed 49 patients with Behçet’s disease, finding that 17 (35%) developed hypopyon over 6–10 years of follow-up.2 The incidence of hypopyon for other forms of uveitis is unclear.

Data regarding the risk factors for hypopyon and regarding its prognostic significance are limited. Nussenblatt et al reported that the occurrence of hypopyon did not worsen the visual prognosis of patients with Behçet’s disease.3 However, the relationship between hypopyon and subsequent outcome in other forms of uveitis is not well understood.

In order to better characterize the risk and importance of hypopyon, here we report the incidence rate, the risk factors, and the risk of adverse outcomes in a large cohort of patients with uveitis.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

The design of the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study has been detailed elsewhere.4 In brief, the SITE Cohort Study is a retrospective cohort study of patients with inflammatory eye diseases seen at five tertiary ocular inflammation centers in the United States from the inception of these centers. One of these centers used a co-management approach, which resulted in ascertainment of clinical outcomes substantially later than they occurred. To avoid this bias, patients from this clinic were excluded from this report. Patients reported here were seen between 1978 and 2007.

DATA COLLECTION

Information on patients with inflammatory eye disease was entered into a database using a computer-based standardized data entry form set specifically prepared for the SITE Cohort Study. For this study, patients from four sites were included. . At the largest site clinic, an approximate 40% random sample of patients were included due to logistical and funding constraints. A random sampling was performed to avoid bias in selecting the sample to be studied. The data collection system included extensive intrinsic quality control checks, requiring correction of errors in real time. Only data from patients with non-infectious uveitis were included in the study; patients with known HIV infection were excluded.

Data collected that are relevant to this study include: demographic characteristics, ocular inflammatory diagnoses, diagnosis of systemic inflammatory disease(s), ophthalmologic examination findings, and ocular surgeries. HLA-B27 testing was done when clinically indicated based on symptoms and clinical findings. The possibility of systemic inflammatory disease diagnoses coexisting with ocular inflammation was aggressively pursued by routine questioning; laboratory testing and consultations were obtained when indicated. Systemic inflammatory diagnoses evaluated included Behçet’s disease, Cogan’s syndrome, Crohn’s disease, dermatomyositis, erythema nodosum, familial systemic granulomatosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, pemphigus, polyarteritis nodosum, polymyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, enteropathic arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy), temporal arteritis, Takayasu’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ophthalmologic examinations documented visual acuity, intraocular pressure (IOP), inflammatory disease activity, and the presence of inflammatory disease sequelae.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Both the prevalence of hypopyon at cohort entry and the incidence of hypopyon were assessed. To calculate the incidence of hypopyon, patients who were free of hypopyon at the time of cohort entry and had follow-up visits were followed until the first occurrence of hypopyon, until the patient ceased attending the clinic, or until completion of the study. Variables including age, sex, race (black, white, or other), type of uveitis (anterior only, intermediate +/− anterior, and posterior or panuveitis), primary ocular diagnoses, HLA-B27 status, and the presence of systemic inflammatory disease were assessed as potential risk factors for incident hypopyon.

The incidence rates for worsening or improvement in visual acuity were assessed by the number of eyes per eye-year which worsened to 20/50 or worse (visual impairment) and 20/200 or worse (legal blindness), by the number of eyes that lost or gained 3 lines of visual acuity, and by the number of eyes that improved to 20/40 or better or to 20/200 or better from a worse level of visual acuity at the time of presentation.

The incidence of band keratopathy, posterior synechaie, ocular hypertension (IOP ≥ 21 mm Hg and ≥ 30mm Hg), hypotony (IOP ≤ 5mm Hg), cataract surgery, glaucoma surgery, macular edema and epiretinal membrane among eyes initially free of each of these was noted (the latter two based on clinical exam supplemented by fluorescein angiography or optical coherence tomography when clinically indicated).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The prevalence of hypopyon was calculated as the number of patients with a hypopyon at cohort entry, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated assuming a binomial distribution. The incidence of hypopyon per person-year among patients initially free of hypopyon who were followed over time was calculated and a 95% confidence interval generated assuming a Poisson distribution. Potential risk factors for incidence of hypopyon were evaluated based on hazard ratios (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals calculated using Cox regression.5

The incidence rates of adverse or favorable events in post-hypopyon eyes with respect to eyes that never were observed to have hypopyon were calculated as the number of events per eye-year assuming a Poisson distribution. Their incidence rates were compared using Poisson regression, adjusting for inter-eye correlation using generalized estimating equations-based methods.6 The data analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION

A total of 4,911 patients with uveitis were included in this analysis (see Table 1). The median age was 39 years, with ages ranging from 4 months to 97 years. Patients were predominantly female (63%) and Caucasian (71%). By anatomic classification of the site of inflammation,7;8 54% had anterior uveitis only, 17% had intermediate (+/− anterior) uveitis, and 29% had posterior or panuveitis. There were 41 cases of hypopyon at the time of cohort entry, a prevalence of 8.4 per 1,000 (95% confidence interval (CI): 6.0–11 per 1,000). Among patients presenting with hypopyon, 15 (37%) patients were HLA-B27 positive, 7 (17%) had a spondyloarthropathy (6 of whom also were HLA-B27 positive), 8 (20%) had Behçet’s disease, 1 (2%) had systemic lupus erythematosus, 1 (2%) had inflammatory bowel disease, and 1 (2%) had juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The remaining 15 (37%) cases of hypopyon at the time of presentation occurred in patients not known to have systemic inflammatory conditions or HLA-B27 associated with uveitis.

Table 1.

Prevalence of hypopyon at the time of cohort entry

| Characteristic | Patients | Cases of Hypopyon | % | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cases | 4911 | 41 | 0.83% | 0.62%–1.13% |

|

Age at Uveitis Diagnosis (years) | ||||

| <18 | 805 | 3 | 0.37% | 0.13%–1.09% |

| 18–25 | 590 | 8 | 1.4% | 0.69%–2.65% |

| 26–35 | 1027 | 14 | 1.4% | 0.81%–2.28% |

| 36–45 | 930 | 7 | 0.75% | 0.37%–1.55% |

| 46–55 | 694 | 7 | 1.0% | 0.49%–2.07% |

| 56–65 | 424 | 1 | 0.24% | 0.04%–1.32% |

| >65 | 395 | 1 | 0.25% | 0.04%–1.42% |

|

Gender | ||||

| Female | 3104 | 17 | 0.55% | 0.34%–0.88% |

| Male | 1806 | 24 | 1.3% | 0.89%–1.97% |

|

Race | ||||

| White | 3497 | 23 | 0.66% | 0.44%–0.99% |

| Black | 992 | 12 | 1.2% | 0.69%–2.10% |

| Other | 422 | 6 | 1.4% | 0.65%–3.07% |

|

Type of uveitis | ||||

| Anterior only | 2632 | 34 | 1.3% | 0.93%–1.80% |

| Primary acute | 317 | 4 | 1.3% | 0.49%–3.20% |

| Recurrent acute | 991 | 20 | 2.0% | 1.31%–3.10% |

| Secondary acute, non-infectious | 80 | 3 | 3.8% | 1.28%–10.5% |

| Chronic | 1165 | 7 | 0.60% | 0.29%–1.24% |

| Intermediate +/− Anterior | 826 | 0 | 0% | 0.00%–0.46% |

| Posterior & Panuveitis | 1453 | 7 | 0.48% | 0.23%–0.99% |

|

Systemic Disease Associations | ||||

| All HLA-B27 positive | 429 | 15 | 3.5% | 1.95%–5.40% |

| Spondyloarthropathy, total | 253 | 7 | 2.8% | 1.35%–5.60% |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 235 | 1 | 0.43% | 0.08%–2.37% |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 118 | 1 | 0.85% | 0.15%–4.64% |

| Behçet’s disease | 128 | 8 | 6.3% | 3.20%–11.9% |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 39 | 1 | 2.6% | 0.45%–13.2% |

| Sarcoidosis | 346 | 0 | 0% | 0.00%–1.10% |

RISK OF HYPOPYON

Of the total patients included in the study, 2,885 patients were free of hypopyon at the time of presentation and were followed for incidence of hypopyon over 9,451 person-years (Table 2). Eighty-one (2.8%) developed hypopyon during follow-up, an incidence of 8.57 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 6.81 – 10.7 per 1,000 person-years). Of these, 19 (23%) were HLA-B27 positive, 12 (15%) had a spondyloarthropathy (HLA-B27 positive or negative), 13 (16%) had Behçet’s disease, 6 (7%) had juvenile idiopathic arthritis, 2 (2%) had rheumatoid arthritis, 2 (2%) had sarcoidosis, and 2 (2%) had inflammatory bowel disease. The remaining 25 incident cases (31%) were not known to have systemic inflammatory conditions or HLA-B27 associated with uveitis.

Table 2.

Risk factors for incidence of hypopyon

| Characteristic | Number of patients at risk | Hypopyon cases | Incidence rate (95% Confidence Interval (CI)) | Crude Relative Risk (RR) of developing hypopyon (95% CI) | Overall p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cases | 2885 | 81 | 0.028 (0.023 – 0.035) | ||

| Age at Uveitis Diagnosis | 0.10 | ||||

| <18 | 419 | 14 | 0.033 (0.020 – 0.055) | Reference | |

| 18–25 | 388 | 16 | 0.041 (0.026 – 0.066) | 1.27 (0.62 – 2.60) | |

| 26–35 | 610 | 24 | 0.039 (0.027 – 0.058) | 1.20 (0.62 – 2.33) | |

| 36–45 | 542 | 10 | 0.018 (0.010 – 0.034) | 0.57 (0.26 – 1.29) | |

| 46–55 | 421 | 6 | 0.014 (0.007 – 0.031) | 0.46 (0.18 – 1.20) | |

| 56–65 | 247 | 3 | 0.012 (0.004 – 0.035) | 0.42 (0.12 – 1.45) | |

| >65 | 234 | 7 | 0.030 (0.015 – 0.060) | 1.09 (0.44 – 2.69) | |

| Gender | 0.36 | ||||

| Female | 1882 | 49 | 0.026 (0.020 – 0.034) | Reference | |

| Male | 1003 | 32 | 0.032 (0.023 – 0.045) | 1.23 (0.79 – 1.92) | |

| Race | 0.56 | ||||

| White | 1994 | 53 | 0.027 (0.020 – 0.035) | Reference | |

| Black | 666 | 21 | 0.032 (0.021 – 0.048) | 1.19 (0.72 – 1.98) | |

| Other | 225 | 7 | 0.031 (0.015 – 0.063) | 1.46 (0.66 – 3.21) | |

| Type of uveitis | 0.03 | ||||

| Anterior | 1513 | 44 | 0.029 (0.022 – 0.039) | Reference | |

| Intermediate or intermediate & anterior | 507 | 6 | 0.012 (0.005 – 0.026) | 0.33 (0.14 – 0.77) | |

| Posterior/panuveitis | 865 | 31 | 0.036 (0.025 – 0.050) | 0.99 (0.62 – 1.56) | |

| Systemic Disease/Laboratory Characteristics | |||||

| HLA-B27* | 286 | 19 | 0.066 (0.043 – 0.101) | 2.60 (1.55 – 4.34) | 0.0003 |

| Spondyloarthropathy, total | 150 | 12 | 0.080 (0.046 – 0.135) | 3.22 (1.75 – 5.95) | 0.0002 |

| Spondyloarthropathy, HLA-B27 positive | 80 | 10 | 0.125 (0.069 – 0.215) | 4.39 (2.26 – 8.51) | <0.0001 |

| Spondyloarthropathy, HLA-B27 negative or missing | 70 | 2 | 0.029 (0.008 – 0.098) | 1.23 (0.30 – 5.02) | 0.77 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 142 | 6 | 0.042 (0.020 – 0.089) | 1.32 (0.57 – 3.02) | 0.52 |

| Sarcoidosis | 245 | 2 | 0.008 (0.002 – 0.029) | 0.22 (0.06 – 0.90) | 0.04 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 71 | 2 | 0.028 (0.008 – 0.097) | 0.86 (0.21 – 3.50) | 0.83 |

| Behçet’s disease** | 85 | 13 | 0.153 (0.092 – 0.244) | 4.93 (2.72 – 8.93) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 50 | 2 | 0.040 (0.011 – 0.135) | 1.57 (0.39 – 6.38) | 0.53 |

HLA-B27 vs. not HLA-B27-associated,

Behçet’s disease vs. all other forms of uveitis

RISK FACTORS FOR HYPOPYON

Crude results regarding risk factors for hypopyon are given in Table 2; results adjusted for potential confounding are given in Table 3. Age, gender, and race were not statistically significant risk factors for incident hypopyon. Patients with intermediate (+/− anterior) uveitis had a lower hypopyon incidence than patients with only anterior uveitis (adjusted relative risk (RR)=0.35, 95 % CI: 0.15 – 0.85). Patients with posterior or panuveitis had an incidence of hypopyon similar to that for patients with anterior uveitis only (adjusted RR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.52 – 1.51). Among the subset of patients with anterior uveitis only, patients with recurrent acute anterior uveitis tended to have higher incidence of hypopyon than patients with chronic anterior uveitis, but not to a statistically significant degree (crude RR=1.62, 95% CI: 0.89 – 2.94).

Table 3.

Cox regression: risk factors for hypopyon adjusted for selected other factors

| Model 1: With HLA-B27 | Model 2: With Spondyloarthropathy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Relative Risk (RR) (95% Confidence Interval (CI)) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Type of uveitis | 0.07 | 0.051 | ||

| Anterior | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate +/− anterior | 0.35 (0.15 – 0.85) | 0.02 | 0.34 (0.14 – 0.81) | 0.02 |

| Posterior/panuveitis | 0.88 (0.52 – 1.51) | 0.65 | 0.87 (0.51 – 1.48) | 0.62 |

| HLA-B27 | 2.04 (1.17 – 3.56) | 0.01 | ||

| Spondyloarthropathy | 2.86 (1.48 – 5.52) | 0.002 | ||

| Sarcoidosis | 0.28 (0.07 – 1.15) | 0.08 | 0.28 (0.07 – 1.14) | 0.08 |

| Behçet’s disease | 4.87 (2.54 – 9.37) | <0.0001 | 5.30 (2.76 – 10.2) | <0.0001 |

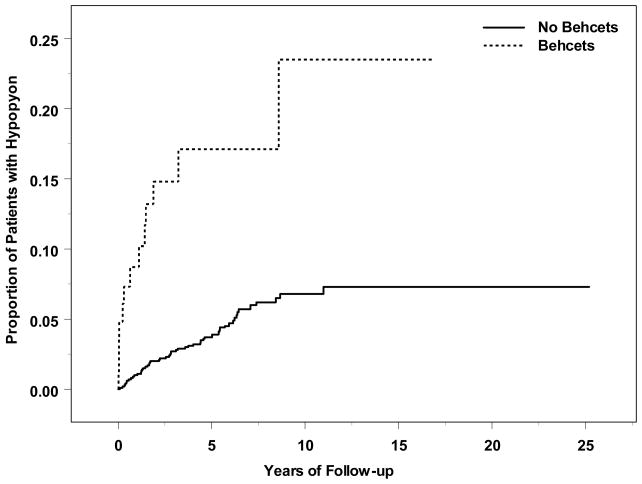

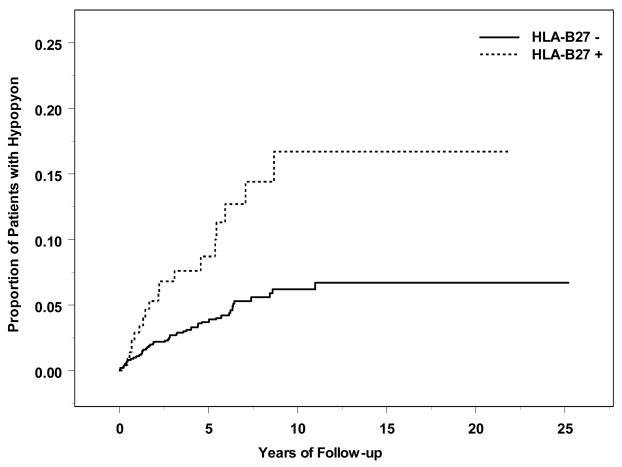

Systemic inflammatory diagnoses associated with increased risk of incident hypopyon included Behçet’s disease (adjusted RR=5.30, 95% CI: 2.76–10.2; see Figure 1) and spondyloarthropathy (adjusted RR=2.86, 95% CI: 1.48–5.52). HLA-B27 positivity was strongly correlated with spondyloarthropathy; in a separate multiple regression omitting the spondyloarthropathy variable, positive HLA-B27 status also was associated with increased risk of hypopyon (adjusted RR=2.04, 95% CI: 1.17–3.56; see Figure 2). Among patients who were both HLA-B27 positive and diagnosed with a spondyloarthropathy, risk tended to be higher than with either factor alone (crude RR=4.39, 95% CI: 2.26–8.51). Sarcoidosis tended to be associated with lower risk of developing hypopyon (crude RR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.06–0.90, adjusted RR=0.29, 95% CI: 0.07 – 1.18).

Figure 1.

Time-to-hypopyon, by Behçet’s Disease Status

Figure 2.

Time-to-hypopyon, by HLA-B27 Status

INCIDENCE OF STRUCTURAL OCULAR COMPLICATIONS AND VISUAL ACUITY CHANGES

Patients with prevalent or incident hypopyon (in aggregate) were followed for a median of 1.56 years after observation of the hypopyon compared to 1.62 years for those never observed to have a hypopyon (p=0.92). The incidences of ocular complications and of visual acuity changes are summarized in Table 4. Eyes with hypopyon, which often had poor visual acuity at the time hypopyon was observed, were more likely to gain 3 lines of visual acuity thereafter compared to eyes of patients who never developed hypopyon followed from their first clinic visit (crude RR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.05–2.24). Post-hypopyon eyes also had a decreased incidence of developing 20/200 or worse visual acuity (crude RR=0.41, 95% CI: 0.17–0.99) than eyes which never developed hypopyon. There was no difference in the incidence of improvement to 20/40 or better and to 20/200 or better between eyes with and without hypopyon. Post-hypopyon eyes fared similarly or better than eyes never observed to have hypopyon in all of the visual acuity analyses.

Table 4.

Occurrence of Adverse and Favorable Events in Eyes Observed and Not Observed to Have Hypopyon*

| Hypopyon Observed | Hypopyon Never Observed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Eyes at risk | Events | Events/Eye-year (EY) (95% Confidence Interval (CI)) | Eyes | Events | Events/Eye-year (EY) (95%CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

| Structural Ocular Complications | |||||||

| Band Keratopathy | 105 | 4 | 0.009 (0.003 – 0.023) | 4032 | 158 | 0.011 (0.009 – 0.013) | 0.83 (0.31 – 2.22) |

| Posterior Synechiae | 58 | 14 | 0.068 (0.036 – 0.127) | 3940 | 523 | 0.046 (0.041 – 0.051) | 1.64 (0.92 – 2.92) |

| Ocular Hypertension (≥21 mm Hg) | 80 | 30 | 0.155 (0.095 – 0.253) | 4287 | 1436 | 0.152 (0.140 – 0.165) | 1.08 (0.73 – 1.58) |

| Ocular Hypertension (≥30 mm Hg) | 103 | 15 | 0.043 (0.025 – 0.076) | 4715 | 605 | 0.043 (0.039 – 0.047) | 1.04 (0.61 – 1.77) |

| Hypotony (<5mm Hg) | 108 | 9 | 0.022 (0.011 – 0.043) | 4772 | 264 | 0.017 (0.015 – 0.019) | 1.30 (0.67 – 2.55) |

| Cataract Surgery | 90 | 18 | 0.054 (0.031 – 0.094) | 4250 | 797 | 0.069 (0.063 – 0.076) | 0.83 (0.49 – 1.41) |

| Glaucoma Surgery | 115 | 6 | 0.013 (0.006 – 0.030) | 4785 | 150 | 0.010 (0.008 – 0.012) | 1.44 (0.63 – 3.25) |

| Macular Edema | 87 | 19 | 0.076 (0.042 – 0.136) | 3972 | 890 | 0.090 (0.082 – 0.099) | 0.92 (0.55 – 1.53) |

| Epiretinal Membrane | 98 | 19 | 0.059 (0.035 – 0.102) | 4467 | 881 | 0.071 (0.065 – 0.078) | 0.88 (0.53 – 1.44) |

| Any of the Above | 30 | 17 | 0.257 (0.116 – 0.569) | 2391 | 1099 | 0.278 (0.252 – 0.307) | 1.18 (0.66 – 2.11) |

| Visual Acuity Change | |||||||

| To 20/50 or Worse | 23 | 4 | 0.053 (0.019 – 0.151) | 2880 | 865 | 0.138 (0.127 – 0.151) | 0.45 (0.17 – 1.20) |

| To 20/200 or Worse | 51 | 5 | 0.025 (0.010 – 0.063) | 3988 | 737 | 0.070 (0.064 – 0.076) | 0.41 (0.17 – 0.99) |

| Loss of 3 lines | 72 | 18 | 0.076 (0.044 – 0.132) | 4946 | 1525 | 0.133 (0.124 – 0.142) | 0.66 (0.40 – 1.09) |

| Gain of 3 lines | 82 | 37 | 0.178 (0.109 – 0.291) | 4946 | 1498 | 0.131 (0.121 – 0.142) | 1.54 (1.05 – 2.24) |

| Improving to 20/40 or Better | 56 | 25 | 0.187 (0.102 – 0.342) | 2112 | 989 | 0.240 (0.214 – 0.268) | 0.93 (0.58 – 1.50) |

| Improving to Better Than 20/200 | 27 | 15 | 0.386 (0.162 – 0.921) | 1004 | 539 | 0.339 (0.288 – 0.399) | 1.15 (0.63 – 2.09) |

For eyes with hypopyon, the initial characteristics reflect those present at the time the hypopyon was first noted. Eyes without hypopyon consist of those never observed to have a hypopyon at presentation or during follow-up. Eye-time prior to occurrence of hypopyon in eyes that later developed a hypopyon is excluded (because such eyes may have had a hypopyon prior to observation).

Eyes with only one visit were excluded. Eyes with complications before the hypopyon were excluded from analyses regarding that complication.

The incidences of ocular hypertension (IOP≥21 mm Hg and IO≥30 mm Hg), cataract surgery, macular edema, and epiretinal membrane were similar for post-hypopyon eyes and other eyes with uveitis. The incidences of posterior synechiae (HR=1.64, 95% CI: 0.92 – 2.92), hypotony (IOP <5 mm Hg) (HR=1.30, 95% CI: 0.67 – 2.55), and glaucoma surgery (HR=1.44, 95% CI: 0.63 – 3.25) were somewhat higher in post-hypotony eyes than other eyes, and confidence intervals included the possibility of a two-fold or greater increase in risk following hypopyon, but the differences were not statistically significant. The incidence of band keratopathy was low in both groups, limiting the ability to compare its risk between groups.

Discussion

Our results indicate that hypopyon affects relatively few patients with uveitis, occurring in an estimated 8.57 patients per 1000 person-years (0.86%). In our experience, hypopyon was more common among patients with uveitis limited to the anterior chamber than in patients who had intermediate uveitis as a part of their ocular inflammation, but was nearly as frequent among patients with posterior or panuveitis. The incidence of hypopyon was increased substantially with certain systemic diseases, especially Behçet’s Disease—which conferred an approximate 5-fold increased risk of hypopyon—and HLA-B27 positivity which was associated with a two-fold or greater increased incidence of hypopyon.

The incidence of hypopyon in our series seems lower than that of D’Alessandro, et al, who observed hypopyon in 4.6% of a series of patients with anterior uveitis.1 However, because the duration of follow-up was not reported, the results cannot be directly compared. A higher proportion of patients in their series were HLA-B27 positive (40% vs. 8% in our study), which may have contributed to this suggestion of a difference. Both studies found similar associations between HLA-B27 positivity and the incidence of hypopyon: D’Alessandro, et al, reported that 8.6% of patients with HLA-B27 positivity developed hypopyon whereas our study found a 6.0%/person-year (95% CI: 4.0–9.0%) incidence of hypopyon among HLA-B27 positive patients.

Among patients with Behçet’s disease, previous studies have reported that 12–35% of patients develop hypopyon (person-years not reported).9;10 In our study, 15.3% of Behcet’s Disease patients developed hypopyon during follow-up (a 35.6%/person-year incidence rate). While direct comparison is difficult without comparable denominators,11 to the extent that the incidence of hypopyon in our study may have been on the low end of this spectrum may reflect the aggressive use of systemic immunosuppression implemented in our practices, which were selected to participate in the SITE Cohort Study in part on the basis of frequent use of immunosuppressive therapy.12

These results suggest that the observation of a hypopyon implies a greater likelihood that Behcet’s disease, HLA-B27 positivity, and/or a spondyloarthropathy is present, and perhaps a lower likelihood that sarcoidosis is present. However, the risk ratios are generally not high enough to rule in (or out) these conditions without other corroborating evidence. Because the large majority of patients with all of these conditions did not develop hypopyon, the absence of hypopyon is not a helpful finding for diagnosing associated systemic inflammatory diseases.

Even though hypopyon can be interpreted as an indicator of exceptionally severe inflammation, eyes which developed hypopyon did not appear to suffer adverse visual outcomes more often than other eyes with uveitis. Although the number of events was small for loss of visual acuity to 20/50 or worse and to 20/200 or worse, the estimated hazard in post-hypopyon eyes for each of these outcomes was less than half that in other eyes, making it very unlikely that the subsequent clinical course of post-hypopyon eyes is associated with a substantially higher risk of further visual loss than for other eyes with uveitis. This observation is consistent with a prior study of visual outcomes in patients with Behcet’s disease.3 Indeed, patients who developed hypopyon were more likely to gain 3 lines of vision at any point during follow-up, probably because the hazy media associated with a hypopyon was a reversible cause of vision loss. It is less easy to explain why patients who developed hypopyon were significantly less likely to develop 20/200 or worse visual acuity compared to patients who never developed hypopyon. The theory that more highly symptomatic disease leads to more demand for therapy, which in turn may avert adverse visual outcomes, is one possibility.

Although post-hypopyon eyes did not have a significantly higher incidence of structural ocular complications during subsequent follow-up than other eyes, for some of these outcomes (posterior synechiae, hypotony, glaucoma surgery, band keratopathy) the number of events was small enough that two-fold increases in the risk of an event could be possible given the limited number of events observed. However, the incidence of ocular hypertension, cataract surgery, cystoid macular edema, and epiretinal membrane was similar in the two groups, with estimated risk ratios close to 1 and 95% confidence intervals not consistent with large increases in risk in post-hypopyon eyes relative to other uveitic eyes. Hypopyon is an event sufficiently rare that our sample size was insufficient to ascertain, with reasonable statistical power, the extent to which the prognosis of hypopyon may interact with underlying systemic diagnosis (e.g., Behçet’s Disease vs spondyloarthropathies) to affect the risk of subsequent adverse outcomes.

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients with accordingly greater ability to precisely estimate rates and associations than in previous reports. We followed a standardized protocol for chart reviews supported by detailed study documentation and site visiting for protocol enforcement to optimize data quality. In accordance with expert panel recommendations,8 we used rates of specific outcomes—such as gain of 3 lines of vision, calculated per eye-year—instead of “final visit” outcomes to avoid the bias introduced by reporting proportions based on variable follow-up time.

The limitations of this study arise from its retrospective nature, wherein some hypopyon events may have cleared before being detected, and follow-up is likely less complete than it would have been in a prospective study. Given the severity of symptoms typically associated with hypopyon, and the need for treatment to promptly clear a hypopyon, it is unlikely that large numbers of established patients of ocular inflammation specialists would have been missed when a hypopyon occurred. However, our estimates of the absolute risk of hypopyon may be slightly low because of missed cases. Fortunately, misclassification of a small number of eyes into the very large group without hypopyon should have little impact on relative risk estimates. The problem of incomplete follow-up was addressed in our statistical analysis by using incidence rates and survival analysis, methods which accommodate losses to follow-up. The median follow-up for post-hypopyon eyes and other eyes was similar. Power limitations for some analyses were discussed previously. Another limitation was potential referral bias, because patients were derived from tertiary care centers which tend to have more severe cases than are found in other practice settings. Thus, our estimates of presenting prevalence and incidence are likely high with respect to non-tertiary practice settings. It is possible that HLA-B27 positivity and systemic diseases may have been unrecognized in some cases, in which case the relative risk of hypopyon associated with HLA-B27, Behçet’s Disease, and spondyloarthropathy may be underestimated.

In summary, this study indicates that hypopyon is an uncommon occurrence in patients with uveitis, occurring in less than 1% per year, even in tertiary uveitis practices. Behçet’s disease, HLA-B27 positivity, and a spondyloarthropathy diagnosis are risk factors for hypopyon. Patients who develop hypopyon do not appear to have increased risk of structural ocular complications or vision loss when managed in a tertiary ocular inflammation practice setting, typically with aggressive topical, oral and/or periocular corticosteroid therapy.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported primarily by National Eye Institute Grant EY014943 (Dr. Kempen). Additional support was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness and the Paul and Evanina Mackall Foundation. Dr Kempen is a Research to Prevent Blindness James S. Adams Special Scholar Award recipient. Drs. Jabs and Rosenbaum are Research to Prevent Blindness Senior Scientific Investigator Award recipients. Dr. Thorne is a Research to Prevent Blindness Harrington Special Scholar Award recipient. Dr. Suhler also received support from the Veteran’s Affairs Administration. Dr. Levy-Clarke was previously supported by and Dr. Nussenblatt continues to be supported by intramural funds of the National Eye Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.D’Alessandro LP, Forster DJ, Rao NA. Anterior uveitis and hypopyon. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:317–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76733-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BenEzra D, Cohen E. Treatment and visual prognosis in Behcet’s disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:589–92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.8.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussenblatt RB. Uveitis in Behcet’s disease. Int Rev Immunol. 1997;14:67–79. doi: 10.3109/08830189709116845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Gangaputra S, et al. Methods for identifying long-term adverse effects of treatment in patients with eye diseases: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:47–55. doi: 10.1080/09286580701585892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of Survival Data. London: Chapman and Hall; 1984. pp. 91–107. Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch-Michel E, Nussenblatt RB. International Uveitis Study Group recommendations for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:234–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barra C, Belfort Junior R, Abreu MT, et al. Behcet’s disease in Brazil--a review of 49 cases with emphasis on ophthalmic manifestations. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1991;35:339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishima S, Masuda K, Izawa Y, et al. The Eighth Frederick H. Verhoeff Lecture, presented by Saiichi Mishima, MD. Behcet’s disease in Japan: ophthalmologic aspects. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:225–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabs DA. Improving the reporting of clinical case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:900–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kump LI, Moeller KL, Reed GF, et al. Behcet’s disease: comparing 3 decades of treatment response at the National Eye Institute. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:468–72. doi: 10.1139/i08-080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]