Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that black patients with pancreatic cancer are less likely to be resected and have worse overall survival. Our goal is to identify if the disparities occur at the point of surgical evaluation or after evaluation has taken place.

Methods

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked data (1992-2002). Black and white patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer were compared in univariate models. Logistic regression was used to determine the effect of race on surgical evaluation and on surgical resection after evaluation. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine factors influencing 2-year survival.

Results

9% of the 3,777 patients were black. Blacks were substantially less likely than whites to undergo evaluation by a surgeon (OR=0.57, 95% CI, 0.42 – 0.77) adjusting for demographics, tumor characteristics, evaluation, SES, and year of diagnosis. Patients who were younger and had fewer comorbidities, abdominal imaging, and a primary care physician were more likely to undergo surgical evaluation. Once seen by a surgeon, blacks were still less likely than whites to be resected (OR=0.64, 95% CI, 0.49 – 0.84). While black patients had decreased survival in an unadjusted model, race was no longer significant after accounting for resection.

Conclusions

29% of black patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancers never receive surgical evaluation. Without surgical evaluation, patients cannot make an informed decision and will not be offered resection. Attaining higher rates of surgical evaluation in black patients would be the first step to eliminating the observed disparity in resection.

Introduction

In 2008, there were an estimated 37,680 new cases and 34,290 deaths from pancreatic cancer, making this disease the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in both men and women in the United States.1 At the current time, surgical resection remains the only method for cure. Despite this fact, recent population-based studies have shown a national failure to operate upon patients with early stage pancreatic cancer. 2-4

A 2006 study based on California Tumor Registry data demonstrated that only 35% of patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer underwent surgical resection.3 Another study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data showed similar findings, with fewer than one third of SEER patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer undergoing surgical resection.4 In both studies, information on the proportion of patients who were unresectable due to locally advanced disease was not provided. Therefore, these studies may overestimate the underutilization of surgical resection. A study using the National Cancer Data Bank (NCDB) evaluated patients with localized pancreatic cancer only. Patients with localized disease are all technically resectable, as disease is confined to the pancreas and does not involve the surrounding structures. Only 28.6% of these patients underwent surgical resection.2

Racial disparities have also been noted in patients with pancreatic cancer. There overall survival observed in black patients is worse than the survival in white patients. A recent study using SEER-Medicare linked data demonstrated that black patients had lower resection rates than white patients. The paper identifies increasing surgical resection rates in black patients as a key component to reducing the observed disparities.5

Eliminating racial disparities in health care is a national priority.6-9 Many previous studies have evaluated racial differences in both the treatment and outcomes between black and white patients with lung,10 colorectal,11 breast,12-14 endometrial cancer,15 and many other cancers.

Surgical resection for locoregional pancreatic cancer can be viewed as a two-step process. In order for a patient to undergo surgical resection he or she must first be evaluated by a surgeon. It is the surgeon who reviews the imaging studies, determines resectability, assesses operative risk, and educates the patient regarding the risks and both long- and short-term benefits of resection. Therefore, there are three objectives of our study. The first objective is to test the hypothesis that racial disparities in the use of surgical resection for locoregional pancreatic cancer is partly attributable to lower rates of surgical evaluation in black patients. Next, we will evaluate racial disparities in the receipt of surgical resection after preoperative surgical evaluation. Finally, we will perform a survival analysis to determine if the observed racial disparities in long-term survival no longer exist after adjusting for surgical resection.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Data Source

We used data from the SEER-Medicare Linked Data Project (SMLDP) for the analysis. The SEER tumor registry, sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), is a database of cancer incidence and survival representative of the U.S. population that currently contains greater than three million cases; 170,000 new cases are added annually. The database includes information on patient demographics, primary tumor site, stage of disease, first course of therapy, and survival.16

The SMLDP includes the SEER Program, the NCI, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).17 93% of all SEER patients older than age 65 are matched with Medicare enrollment files. Claims data for hospital stays, physician services, and hospital outpatient visits are included. A Data Use Agreement has been signed. The data used in this proposal include SEER subjects through 2002 and their Medicare claims through 2003.

Patient Cohort Selection

Using the SEER-Medicare linked data, the following subjects were included in the study: 1) patients with ICD-O-3 histology codes consistent with adenocarcinoma to eliminate other pancreatic tumor types such as neuroendocrine and acinar cell cancers, 2) patients with localized or regional (locoregional) pancreatic cancer based on SEER historic stage as described below in “Stage and Resectablity”, 3) patients diagnosed between 1992-2002, 4) patients with a pancreatic cancer as their first primary cancer, 5) patients enrolled in both Medicare Part A and Part B without HMO for 12 months before their cancer diagnosis and for three months after their diagnosis, 6) patients aged ≥ 66 (to ensure available Medicare claims data for a full year prior to diagnosis), 7) patients who survived more than three months after the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and 8) non-hispanic white and black patients only. Patients diagnosed at autopsy only or patients diagnosed by death certificate only were excluded.

Stage and Resectabilty

SEER does not provide AJCC stage for pancreatic cancer. Therefore, SEER historic stage was used. Locoregional pancreatic cancer, as defined by the SEER Program includes localized disease (stage 0, IA, and IB) and regional disease (stage IIA, IIB, and III). All patients with localized disease are technically resectable. However, some patients with regional disease are not resectable due to locally advanced disease. Locally advanced disease includes T3 tumors with major involvement of the superior mesenteric vein, portal vein, or retroperitoneum and those with T4 tumors involving the celiac axis. Table 1 correlates AJCC stage with SEER historic stage and resectability.

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Pancreatic Cancer Staging, SEER Historic Staging, and Technical Resectability.

| PRIMARY TUMOR (P) | ||

| TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

| T0: No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis: Carcinoma in situ | ||

| T1: Tumor is limited to the pancreas and is 2 cm or less in greatest dimension | ||

| T2: Tumor is limited to the pancreas and is more than 2 cm in greatest dimension | ||

| T3: Tumor extends beyond the pancreas without involvement of the celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery | ||

| T4: Tumor involves the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery (unresectable primary tumor) | ||

| REGIONAL LYMPH NODES (N) | ||

| NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

| N0: No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| N1: Regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| DISTANT METASTASIS (M) | ||

| MX: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | ||

| M0: No distant metastasis | ||

| M1: Distant metastasis | ||

| AJCC STAGING GROUPS | SEER HISTORIC STAGING | RESECTABILITY |

| Stage 0: Tis, N0, M0 | Localized | Resectable |

| Stage IA: T1, N0, M0 | Localized | Resectable |

| Stage IB: T2, N0, M0 | Localized | Resectable |

| Stage IIA: T3, N0, M0 | Regional | Potentially resectable* |

| Stage IIB: T1-3, N1, M0 | Regional | Potentially resectable* |

| Stage III: T4, any N, M0 | Regional | Unresectable |

| Stage IV: Any T, any N, M1 | Distant | Unresectable |

Resectable if no major portal/superior mesenteric venous involvement or major retroperitoneal involvement present (locally advanced disease).

To determine resectability we used the SEER extent of disease (EOD) codes for pancreas (head, body, and tail).18 SEER Extent of Disease (EOD) coding has gone through several revisions and now includes schemes for all sites of cancer. The EOD coding scheme consists of a ten-digit code. It incorporates three digits for the size and/or involvement of the primary tumor, two for the extension of the tumor, and one more as a general code for lymph node involvement. Four more digits are used after these six: two for the number of pathologically positive regional lymph nodes and two more for the number of regional lymph nodes that are pathologically examined. The code is based on clinical, operative, and pathological diagnoses of the cancer.

The two digit extension code was used to determine the presence of locally advanced disease and resectability. The codes were classified as resectable (10, 30, 40, 44, 45, 48, 50, 52, 62, and 64) and unresectable (54, 56, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 85, 99). The formal definitions can be found in the SEER EOD coding book.18 We included any portal/superior mesenteric venous involvement as unresectable in an effort to make a conservative estimate for resectability, though some centers advocate resection of these structures if involvement is limited.19, 20 In addition, 93 patients had unknown EOD codes (99). These were also included as unresectable so as not to overestimate the number of resectable patients.

The staging reported in SEER is based on clinical staging (including radiology) in patients who did not undergo surgical resection and pathologic staging in patients who were resected. The pathologic staging is more accurate and patients thought to have localized disease are often upstaged to regional disease following surgical resection. To avoid this upstaging bias, we evaluated patients with locoregional disease as a group and did not compare localized to regional disease.

Variable Definitions

A patient was considered to have undergone surgical evaluation if he or she had surgery or was seen by surgeon as identified by the Unique Physician Identification Number (UPIN) and Medicare specialty codes on claims for “surgeon.” Visits to oncologists and gastroenterologists were determined in similar fashion using the UPIN and Medicare specialty codes for “oncology” and “gastroenterology.” Using the Unique Physician Identification Number (UPIN) and Medicare specialty codes on claims, the general practitioner, family physician, internist, or geriatrician who provided most outpatient evaluations in the year prior to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was assigned as a patient's primary care physician. Patients who had no visit to a primary care provider were designated as not having a primary care physician

We used ICD-9 procedure codes to determine whether or not a patient had abdominal imaging via CT or MRI (codes 88.01, 88.02, and 88.97). Hospital and carrier files were used to determine the above information.

A patient was considered to have undergone curative resection if the ICD-9 procedure codes (52.6, 52.7, 52.51, 52.52, 52.53, 52.59) for total pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or other pancreatic resection were found in the Medicare claims inpatient files.

As surrogate markers for socioeconomic status patients were classified into quartiles for income and education levels based on zip code level data. SEER-Medicare does not provide individual level patient data for these variables. Income level was defined using the 2000 median income of the zip code at which the patient lived. Patients were placed into education quartiles by using the percentage of patients in the zip code with less than twelve years of education. As a result, the first quartile has the lowest percentage of patients without a high school education and is the “most educated” quartile. To evaluate the effect of comorbidities, we used Klabunde's modification of the Charlson comorbidity index.21 Patients were classified as having 0, 1, 2 or ≥3 comorbidities.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1.3 (Cary, N.C.). The primary outcome variable was the odds of surgical resection in black patients compared to white patients. We first performed a univariate analysis of black compared to white patients with pancreatic cancer. We evaluated differences in other demographic characteristics (age, gender, comorbidities), tumor characteristics (resectability, location of cancer, nodal status), preoperative evaluation (abdominal imaging, evaluation by a surgeon, oncologist, gastroenterologist), social support (marital status, presence of a primary care physician), socioeconomic status (SEER region, income, education, population), and year of diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for surgical evaluation for black compared to white patients. Next, in the subset of patients evaluated by a surgeon, logistic regression models were used to determine the odds ratios for surgical resection in black compared to white patients.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to compare 2-year survival in black and white patients. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the independent effect of race on 2-year survival.

Results

Overall Cohort

There were 3,777 non-Hispanic white and black patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer in the overall cohort. The mean age of patients was 75.8 ± 6.6 years, with the majority of patients being female (59%). 3,425 patients were white (91%) and 352 were black (9%). The Charlson comorbidity score was zero in 62% of patients. In 58% of cases, patients had an identified primary care physician. Pancreatic cancers were located in the head of the pancreas in 74%, the body/tail in 10%, and in 16% the site was not specified. Cross-sectional abdominal imaging via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) was performed in 95% of patients.

Based on the SEER extent of disease codes, 79% were candidates for surgical resection (resectable) and 21% were unresectable due to involvement of the superior mesenteric vein, portal vein, or organs outside the typical field of resection. Only 29% of the cohort was resected. When stratified by resectability based on SEER EOD codes, 33% of the resectable patients and 13% of the unresectable patients were resected.

Baseline Characteristics: Black vs. White Patients

Table 2 shows the differences in demographic factors, tumor characteristics, evaluation, social support, and socioeconomic status between white and black patients. When compared to white patients, black patients were similar in age, but were more likely to be female, unmarried, and have more comorbidities. Black patients were significantly more likely to be in the lowest quartile for both income and education.

Table 2. Patient and Tumor Characteristics by Racial Status (N=3,777).

| Factor | White (N=3,425) | Black (N=352) | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS | |||

| Age (years) | 75.9 ± 6.6 years | 75.3 ± 6.6years | 0.87 |

| Gender (% male) | 41.2% | 35.2% | 0.02 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 62.7% | 54.3% | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 24.1% | 23.0% | |

| 2 | 8.4% | 12.5% | |

| >=3 | 4.8% | 10/2% | |

| TUMOR CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Resectability based on SEER EOD2 codes | 79.5% | 79.8% | 0.86 |

| Location of cancer | |||

| Pancreatic head | 74.0% | 71.6% | 0.62 |

| Pancreatic body/tail | 10.4% | 11.4% | |

| Unknown | 15.6% | 17.0% | |

| Nodal status | |||

| Negative | 17.8% | 15.3% | 0.23 |

| Positive | 18.9% | 16.7% | |

| Unknown | 63.3% | 67.9% | |

| PREOP EVALUATION | |||

| Abdominal imaging via CT or MRI | 95.1% | 92.1% | 0.01 |

| Seen by oncologist | 54.6% | 47.4% | 0.01 |

| Seen by gastroenterologist | 74.2% | 72.2% | 0.40 |

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 54.6% | 34.9% | <0.0001 |

| Single | 11.8% | 23.3% | |

| Widowed | 30.8% | 38.6% | |

| Unknown | 2.8% | 3.1% | |

| Patient has a primary care physician | 59.2% | 49.4% | <0.0001 |

| SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS | |||

| SEER Region3 | Not shown | Not shown | <0.0001 |

| Income (median income in zip code) | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest income quartile) | 21.3% | 64.2% | <0.0001 |

| Quartile 2 | 25.8% | 20.7% | |

| Quartile 3 | 26.1% | 8.9% | |

| Quartile 4 (highest income quartile) | 26.8% | 6.2% | |

| Education (% in zip code with < high school education) | |||

| Quartile 1 (highest education quartile) | 29.7% | 4.1% | <0.0001 |

| Quartile 2 | 27.0% | 6.2% | |

| Quartile 3 | 24.7% | 24.0% | |

| Quartile 4 (lowest education quartile) | 18.6% | 65.7% | |

| Population | |||

| >1,000,000 | 56.9% | 78.9% | <0.0001 |

| 250,000 – 1,000,000 | 26.7% | 14.2% | |

| <250,000 | 16.4% | 6.8% | |

| UNADJUSTED OUTCOMES | |||

| Surgical resection | 29.7% | 21.3% | 0.0009 |

| Evaluation by a surgeon | 76.8% | 69.0% | 0.001 |

| Surgical resection if evaluated by a surgeon (N=2,872) | 38.7% | 30.9% | 0.02 |

Overall chi-square P-value

EOD = extent of disease

Individual SEER region not shown

Overall, the tumor characteristics were similar between the two groups. Most importantly, the number of patients that were resectable based on SEER EOD codes was similar between the two groups. There were no differences in the location of the cancers within the pancreas or the proportion of black and white patients with unknown tumor site or nodal status. In over 60% of patients the data on nodal status are missing. As this information is largely learned after surgery and pathologic examination, nodal status was not included in the multivariate models evaluating the factors affecting surgical resection.

Black patients were less likely than white patients to have a cross-sectional abdominal imaging study, to be evaluated by an oncologist, or to have a primary care physician. They were equally as likely to be evaluated by a gastroenterologist.

Surgical Evaluation

In locoregional pancreatic cancer, as with any other disease process requiring surgical resection, the first step in achieving surgical resection is evaluation by a surgeon. 31% of all black patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer (N=3,777) and 29% of black patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancers (N=3,002) never receive surgical evaluation, the first step in the process. In an unadjusted model, Black patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer were 32% less likely than white patients to be evaluated by a surgeon (unadjusted OR 0.68, 95% CI, 0.53 – 0.86, unadjusted percentages in Table 2). 3,614 of the 3,777 patients had complete data for the final logistic regression model. After adjusting for demographic factors, tumor characteristics, preoperative evaluation, social support, and socioeconomic status black patients were 43% less likely to be evaluated by a surgeon (OR 0.57, 95% CI, 0.42 – 0.77, Table 3).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analysis Modeling the Odds of Evaluation by a Surgeon*.

| Factor (reference group) | Group | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity (white) | Black | 0.58 | 0.43 – 0.78 |

| Age (continuous) | Per increasing year of age | 0.92 | 0.90 – 0.93 |

| Charlson score (score = 0) | Score = 1 | 0.75 | 0.62 – 0.92 |

| Score = 2 | 0.85 | 0.63 – 1.14 | |

| Score = 3 | 0.54 | 0.38 – 0.76 | |

| Site of tumor (head) | Body/tail | 0.89 | 0.67 – 1.18 |

| Not specified | 0.53 | 0.43 – 0.66 | |

| Abdominal imaging (no) | Imaging | 3.37 | 2.38 – 4.76 |

| Resectable (not resectable) | Resectable | 1.26 | 1.01 – 1.56 |

| Oncology evaluation (no) | Seen by oncology | 1.37 | 1.14 – 1.63 |

| GI evaluation (no) | Seen by GI | 0.71 | 0.57 – 0.87 |

| Primary care physician (no) | Have a PCP | 1.37 | 1.15 – 1.63 |

| SEER Region** | Individual region not shown | Type 3 P-value <0.0001 |

Year of diagnosis, gender, income, education, marital status, and population are controlled for in the above model but did not influence surgical evaluation so OR are not shown.

Individual SEER region (Connecticut, Detroit, Greater California, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Los Angeles, Louisiana, Metropolitan Atlanta, New Jersey, New Mexico, Rural Georgia, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Utah) odds ratios not shown. OR reported above control for SEER region and SEER region influences surgical evaluation, evidenced by the significant type 3 P-value.

Complete data available in 3,614 of 3,777 patients.

In addition to race, several other factors also influenced surgical evaluation (Table 3). Older patients and patients with higher Charlson comorbidity scores were less likely to undergo preoperative surgical evaluation. Patients who were resectable based on SEER EOD codes and had cross-sectional abdominal imaging were more likely to be evaluated by a surgeon. When compared to patients with cancers in the head of the pancreas, those with cancers in the body/tail were equally as likely to be evaluated by a surgeon. Evaluation by a medical oncologist was also predictive of surgical evaluation, while evaluation by a gastroenterologist had the opposite effect. Patients who were identified as having a regular primary care physician were 37% more likely to undergo surgical evaluation. SEER region was also a significant predictor of surgical evaluation, with an overall type 3 P-value of <0.0001 for differences among the SEER regions (Connecticut, Detroit, Greater California, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Los Angeles, Louisiana, Metropolitan Atlanta, New Jersey, New Mexico, Rural Georgia, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, and Seattle-Puget Sound. The individual odds ratios for each region depend on the reference group and are not included in the table. However, it is critical to understand there are regional differences and control for this when evaluating the effect of race on surgical evaluation.

Surgical Resection: Overall and Following Surgical Evaluation

For the overall cohort (n=3,77) regardless of whether surgical evaluation occurred, 30% of white patients but only 21% of black patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer were resected, for an unadjusted OR of 0.64 (95% CI, 0.49 – 0.84). In the subset of 3,002 patients with technically resectable tumors based on SEER EOD codes (regardless of surgical evaluation), 34% of white patients were resected versus 24% of black patients (unadjusted OR = 0.61, 95% CI, 0.46 – 0.81).

There were 2,872 black and white patients who underwent surgical evaluation. Data on all covariates were available in all 2, 872 patients. The unadjusted odds ratio of surgical resection after surgical evaluation for black patients was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.53 – 0.94). After adjusting for all the same factors in the previous models, black patients were 33% less likely to be resected even after surgical evaluation (OR=0.67, 95% CI, 0.48 – 0.95, Table 4).

Table 4. Factors Influencing Surgical Resection After Evaluation by Surgeon*.

| Factor (reference group) | Group | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity (white) | Black | 0.68 | 0.48 – 0.95 |

| Year of diagnosis (continuous) | Per increasing year | 1.10 | 1.07 – 1.33 |

| Age (continuous) | Per increasing year of age | 0.92 | 0.90 – 0.93 |

| Charlson score (score = 0) | Score = 1 | 0.93 | 0.76 – 1.14 |

| Score = 2 | 0.63 | 0.46 – 0.87 | |

| Score = 3 | 0.54 | 0.35 – 0.82 | |

| Resectable (not resectable) | Resectable | 5.73 | 4.45 – 7.38 |

| Site of tumor (head) | Body/tail | 1.34 | 1.02 – 1.77 |

| Not specified | 0.45 | 0.35 – 0.58 | |

| Seen by oncologist (no) | Yes | 0.68 | 0.57 – 0.82 |

Gender, abdominal imaging, evaluation by gastroenterologist, marital status, primary care physician, SEER region, income, education, and population were included in the model but did not influence surgical resection following surgical evaluation.

Complete data available in 2,758 of 2,872 patients.

An analysis was also performed on the 2,267 resectable patients who were evaluated by a surgeon. When considering resectable patients only, black patients were 40% less likely to be resected following surgical evaluation (OR 0.60, 95% CI, 0.41 – 0.87).

Other factors influencing surgical resection after surgical evaluation are shown in Table 4. In the adjusted model, with each increasing year of diagnosis, patients were 10% more likely to be resected. Older patients, those with higher Charlson comorbidity score, and patients with an unknown tumor site were less likely to undergo surgical resection. Patients with tumors in the body and tail were more likely to be resected. Patients who were resectable based on SEER EOD codes were 5.7 times more likely to be resected. Gender, abdominal imaging, evaluation by a gastroenterologist, marital status, primary care physician, SEER region, income, education, and population did not influence surgical resection following surgical evaluation.

Survival Analysis

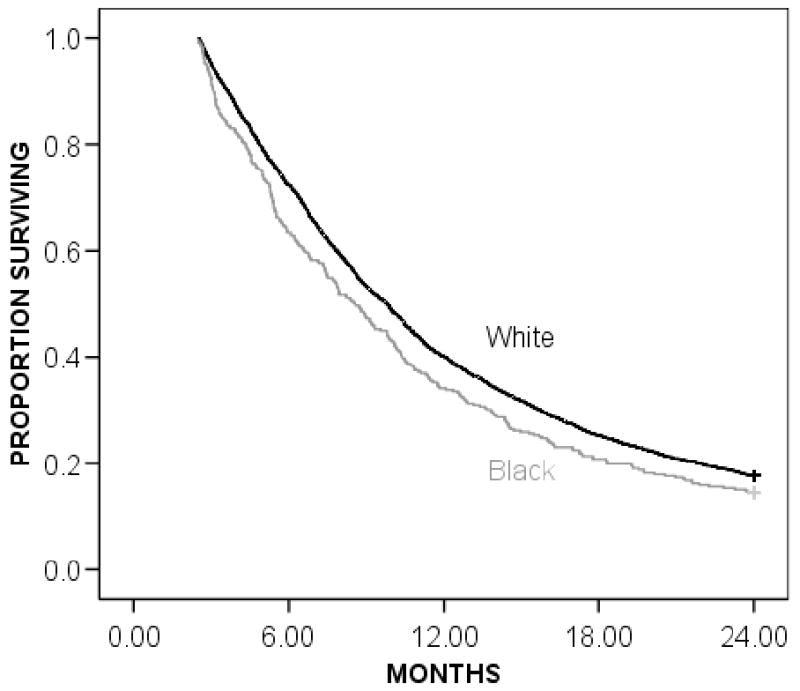

The Kaplan-Meier overall 2-year survival for black versus white patients is shown in Figure 1. In this unadjusted survival curve, black patients had worse overall survival with a median survival of 8.6 months and a 2-year survival rate of 14% compared to 9.8 months and 18% in white patients (P=0.01). The same is true when evaluating resectable patients only (N=3,002). The median survival for resectable black patients was 9.1 months, with a 2-year survival rate of 15%. The median survival for white patients was 9.9 months, with a 2-year survival rate of 19% (P=0.02).

Figure 1.

Overall Kaplan-Meier actuarial 2-year survival for black and white patients. Black patients (gray line) had a median survival rate of 8.6 months and a 2-year survival rate of 14% compared to white patients (black line) who had a median survival rate of 9.8 months and a 2-year survival rate of 18% (P=0.01).

In a Cox proportional hazards model, the unadjusted hazard ratio for black patients was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.04 – 1.32). Surgical resection accounted for a significant proportion of the observed racial difference; when resection alone was added to the model, race was no longer a significant predictor of survival (HR 1.08, 95% CI, 0.96 – 1.22). In the final model adjusting for demographics, resectability, socioeconomic status, social support, and year of diagnosis race remained non-significant (HR 1.00, 95% CI, 0.87 – 1.14). In the final model, younger age (P<0.0001), lower Charlson comorbidity score (P=0.0005), negative lymph nodes, and surgical resection (P<0.0001) were independent predictors of better survival.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer remains the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Currently, surgical resection provides the only opportunity for cure. We and others have reported that surgical resection is underutilized in patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer2-4 and that the underutilization is greater among black patients.5 Black patients are shown to have lower overall survival rates when compared to white patients and increasing surgical resection rates has been identified as a key factor in eliminating this disparity.5

Our study sought to explore these racial differences and evaluated surgical resection in patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer as a two-step process. The first step in achieving surgical resection for patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer is evaluation by a surgeon. Surgical evaluation is critical in the workup of patients with locoregional disease as it is the surgeon who evaluates the imaging studies and determines technical resectability. In addition, the surgeon assesses patient comorbidities, functional status, and other factors to determine operative risk and assesses the long-term prognosis for these patients. Following preoperative surgical evaluation, the second step is the recommendation for and performance of surgical resection in appropriate patients. Previous studies using the same dataset demonstrate that cancer-directed surgery was recommended equally for black and white patients.5

Racial differences in the receipt of optimal therapy and outcomes in a variety of cancers have been attributed to differential access to care22 and differences in beliefs between racial groups. For example, black patients with lung cancer have been shown to be more likely to refuse surgery,23 to believe that tumors may be cured without surgery,24 to fear tumor spread at the time of operation,25 and to distrust health care providers.26

Our study confirms that patients black patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer have lower rates of surgical resection. This occurs at both steps in the two-step process with black patients being 43% less likely to be evaluated by a surgeon, then 36% less likely to be resected following surgical evaluation after adjusting for the differences stated. In addition, when evaluating long-term survival, once surgical resection is accounted for, race is no longer a significant predictor of survival, suggesting that the observed differences are secondary to decreased resection rates in black patients.

Intervening to maximize the number of black patients evaluated by surgeons is the first step to improving the current disparity in surgical therapy for locoregional disease. Despite the possibility of differing racial attitudes and beliefs toward pancreatic cancer, surgical evaluation is necessary for patients to make an informed decision. Such evaluation and education may provide factual information necessary to influence false attitudes and beliefs. In fact, the goal should be for all patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer, regardless of race, to undergo surgical evaluation such that they can make an informed decision regarding surgical resection.

The multivariate model shows that patients with primary care physicians are more likely to undergo surgical evaluation and that blacks are less likely to have a primary care physician. Given this population is 100% insured it is possible for everyone to have a primary care physician. Maximizing the number of patients with primary care physicians may impact referral for surgical evaluation. Educating primary care physicians on the importance of surgical evaluation and surgical resection in patients with locoregional disease could improve referral rates for surgical evaluation. Similarly, this education could improve rates of abdominal imaging in black patients.

The SEER region of diagnosis was a significant independent predictor of receipt of surgical evaluation. As with other disease processes, 27-30 this implies significant variability in care from provider to provider, seen here as regional trends. There need to be clear standards of care for patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer and these standards need to be disseminated to regions who are low outliers in providing this appropriate evaluation.

However, lack of surgical evaluation does not completely explain the disparity in surgical resection rates between blacks and whites. In a model evaluating surgical resection only in patients who had undergone surgical evaluation, black patients were still 32% less likely to undergo surgical resection. The etiology of the racial disparities in surgical resection following surgical evaluation is more difficult to understand and not completely explained by this study. It is possible that despite that fact that these patients are seeing surgeons, they are not seeing surgeons qualified to make decisions regarding their pancreatic cancer. Surgeons who are inexperienced pancreatic surgery may not adequately evaluate CT scans or feel comfortable performing the complex operations necessary to treat this disease. There is strong evidence of a volume-outcome relationship, both at the hospital level and individual surgeon level for pancreatic resection.31-35 as a result, it has been recommended that pancreatic resection be regionalized to specialized “Centers of Excellence” and surgeons with experience in treating this disease. Further studies are needed to determine the characteristics of the evaluating surgeons to further impact racial disparities in surgical resection.

It is also possible that there are significant racial differences in beliefs regarding pancreatic cancer, aggressive surgical therapy, and trust of physicians similar to the beliefs manifested in lung cancer patients.22, 24-26 Little is known about racial attitudes (or patient attitudes in general) toward the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

This study differs from previous studies looking at underutilization of surgical resection since it accounts for patients who have unresectable (locally advanced) disease. We recognize that our assessment of resectability based on the SEER EOD codes may be inaccurate given the retrospective nature of the study and the pitfalls in the collection of registry data. We tried to be conservative in assigning “unresectable” status. This group included all patients with an “unknown” EOD code as well as any patient with any vascular invasion, even though some cancers with vascular invasion may be considered resectable at some major centers.19, 20 Resectability was strongly correlated with surgical resection suggesting these codes are valid.

Because of the administrative nature of the dataset, we may underestimate surgical evaluation. By the design of the study, we identify surgical evaluation only when a surgeon generates a bill for this service. It is possible that some patients' histories and films are reviewed in multidisciplinary conferences and deemed unresectable without generating a bill. While this would cause us to underestimate the number of patients undergoing surgical evaluation, it would presumably happen equally in black and white patients, and would not account for the observed disparity.

In summary, black patients are less likely to see a surgeon and are, therefore, never given the opportunity to make an informed decision regarding surgical resection. Even after surgical evaluation, blacks are less likely to be resected. 29% of black patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancers never receive surgical evaluation. The first step in eliminating racial disparities will be to improve surgical evaluation rates among black patients. Ideally, the goal should be for all patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer, regardless of race, to undergo surgical evaluation such that they can make an informed decision regarding surgical resection. Further studies are needed to evaluate the characteristics of surgeons evaluating these patients as well as patient beliefs to further define the etiology of the racial differences and target areas for improvement in resection following surgical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Work Supported in part by the Dennis W. Jahnigen Career Development Scholars Award, NIH K07 Cancer Prevention, Control, and Population Sciences Career Development Award (Grant Number 1K07CA130983-01A1), the UTMB Center for Population Health and Disparities, (Grant number NIH-5P50CA105631), and Established Investigator Award (NCI -K05 CA 134923)

The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:173–80. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180691579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cress RD, Yin D, Clarke L, Bold R, Holly EA. Survival among patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based study (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:403–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riall TS, Nealon WH, Goodwin JS, et al. Pancreatic cancer in the general population: Improvements in survival over the last decade. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1212–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.010. discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy MM, Simons JP, Hill J, Tseng JF. Pancreatic resection: A key component to reducing racial disparities in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1002/cncr.24433. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Press NA, editor. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the twenty-first century. Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2nd edition. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byers T, Mouchawar J, Marks J, et al. The American Cancer Society challenge goals. How far can cancer rates decline in the U.S. by the year 2015? Cancer. 1999;86:715–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farjah F, Wood DE, Yanez ND, 3rd, et al. Racial disparities among patients with lung cancer who were recommended operative therapy. Arch Surg. 2009;144:14–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry J, Bumpers K, Ogunlade V, et al. Examining racial disparities in colorectal cancer care. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:59–83. doi: 10.1080/07347330802614840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AW, Alfano CM, Reeve BB, et al. Race/ethnicity, physical activity, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:656–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Gillanders WE, Aft R. Racial disparities in the development of breast cancer metastases among older women: a multilevel study. Cancer. 2009;115:731–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Lian M, Gillanders WE, Aft R. The role of poverty rate and racial distribution in the geographic clustering of breast cancer survival among older women: a geographic and multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:554–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allard JE, Maxwell GL. Race disparities between black and white women in the incidence, treatment, and prognosis of endometrial cancer. Cancer Control. 2009;16:53–6. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [Accessed: December 10, 2009]. Available at: http://www.seer.gov/about. [Google Scholar]

- 17.SEER-Medicare Linked Database. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [Accessed: December 10, 2009]. Available at: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SEER Extent of Disease - 1988. Coding and Instructions. National Cancer Institute; 1998. pp. 66–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siriwardana HP, Siriwardena AK. Systematic review of outcome of synchronous portal-superior mesenteric vein resection during pancreatectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:662–73. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng JF, Tamm EP, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Venous resection in pancreatic cancer surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:349–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin LM, Klabunde CN, Green P, Barlow W, Wright G. In search of the perfect comorbidity measure for use with administrative claims data: does it exist? Med Care. 2006;44:745–53. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223475.70440.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulligan CR, Meram AD, Proctor CD, Wu H, Zhu K, Marrogi AJ. Unlimited access to care: effect on racial disparity and prognostic factors in lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:25–31. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCann J, Artinian V, Duhaime L, Lewis JW, Jr, Kvale PA, DiGiovine B. Evaluation of the causes for racial disparity in surgical treatment of early stage lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:3440–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cykert S, Phifer N. Surgical decisions for early stage, non-small cell lung cancer: which racially sensitive perceptions of cancer are likely to explain racial variation in surgery? Med Decis Making. 2003;23:167–76. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03251244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margolis ML, Christie JD, Silvestri GA, Kaiser L, Santiago S, Hansen-Flaschen J. Racial differences pertaining to a belief about lung cancer surgery: results of a multicenter survey. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:558–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, Kelly PA, Souchek J. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients' perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:904–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanc PD, Trupin L, Earnest G, et al. Effects of physician-related factors on adult asthma care, health status, and quality of life. Am J Med. 2003;114:581–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burns RB, Freund KM, Moskowitz MA, Kasten L, Feldman H, McKinlay JB. Physician characteristics: do they influence the evaluation and treatment of breast cancer in older women? Am J Med. 1997;103:263–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominick KL, Skinner CS, Bastian LA, Bosworth HB, Strigo TS, Rimer BK. Provider characteristics and mammography recommendation among women in their 40s and 50s. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:61–71. doi: 10.1089/154099903321154158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Normand SL, et al. Impact of underuse, overuse, and discretionary use on geographic variation in the use of coronary angiography after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2001;39:446–58. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong Y, Gonen M, Rubin D, Radzyner M, Brennan MF. Long-term survival is superior after resection for cancer in high-volume centers. Ann Surg. 2005;242:540–4. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000184190.20289.4b. discussion 4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho V, Heslin MJ. Effect of hospital volume and experience on in-hospital mortality for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;237:509–14. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000059981.13160.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riall TS, Eschbach KA, Townsend CM, Jr, Nealon WH, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Trends and disparities in regionalization of pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1242–51. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0245-5. discussion 51-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Gordon TA, et al. Importance of hospital volume in the overall management of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;228:429–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]