Abstract

The basal forebrain cholinergic system (BFCS) plays a role in several aspects of attentional function. Activation of this system by different afferent inputs is likely to influence how attentional resources are allocated. While it has been recognized for some time that the hypothalamus is a significant source of projections to the basal forebrain, the phenotype(s) of these inputs and the conditions under which their regulation of the BFCS becomes functionally relevant are still unclear. The cell bodies of neurons expressing orexin/hypocretin neuropeptides are restricted to the lateral hypothalamus and contiguous perifornical area but have widespread projections, including to the basal forebrain. Orexin fibers and both orexin receptor subtypes are distributed in cholinergic parts of the basal forebrain, where application of orexin peptides increases cell activity and cortical acetylcholine release. Furthermore, disruption of orexin signaling in the basal forebrain impairs the cholinergic response to an appetitive stimulus. In this review, we propose that orexin inputs to the BFCS form an anatomical substrate for links between arousal and attention, and that these interactions might be particularly important as a means by which interoceptive cues bias allocation of attentional resources toward related exteroceptive stimuli. Dysfunction in orexin-acetylcholine interactions may play a role in the arousal and attentional deficits that accompany neurodegenerative conditions as diverse as drug addiction and age-related cognitive decline.

Keywords: acetylcholine, orexin, hypocretin, basal forebrain, attention, arousal

Introduction

Since the first reports of their discovery in the late 1990’s [31,114] the orexin/hypocretin family of neuropeptides has generated a tremendous amount of interest due to their involvement in a variety of important and interesting physiological phenomena, leading to their description as “physiological integrators” [32]. The cell bodies of orexin/hypocretin neurons are confined to the lateral hypothalamus and contiguous perifornical area, although they project widely to both rostral and caudal brain regions [103]. The peptides produced by the preproorexin gene act on two G protein-coupled receptors; the orexin/hypocretin 1 receptor (Ox1R/HcrtR1), which is selective for orexin A (OxA)/hypocretin 1 and the orexin 2 receptor (Ox2R/HcrtR2), which binds both OxA and orexin B/hypocretin 2 (OxB) with high affinity [2,114]. More definitive descriptions of the specific roles played by these peptides (hereafter referred to as orexins, for simplicity) in certain normal and pathological neural processes will be facilitated by further analysis of their interactions with other brain regions and neurotransmitter systems. The anatomical substrates for these interactions, including for those underlying the putative effects of orexins on attention (the focus of this review), are multitudinous [103]. Orexins likely regulate attention and arousal via interactions with a variety of ascending neuromodulatory systems, including dopamine neurons in the ventral midbrain [41,136] and noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus [6,38,56]. Our labs, however, have focused primarily on orexin interactions with the basal forebrain cholinergic system (BFCS), the principle extrinsic source of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in the mammalian neocortex and a crucial mediator of several aspects of attentional function. We propose that orexin inputs to the BFCS form an anatomical substrate for links between arousal and attention, and that these interactions might be particularly important as a means by which interoceptive cues bias allocation of attentional resources toward related exteroceptive stimuli.

Overview of the basal forebrain cholinergic system role in attention

Attention represents a construct that can be defined and measured based upon manipulation of specific variables, including target number, duration and unpredictability along with the ability to ignore irrelevant stimuli [97,119]. As has been discussed in other reviews [119], attentional processing requires some generalized state of arousal, or a general physiological state of readiness for action. However, brain mechanisms involved in attention can be dissociated from arousal based upon changes in task performance following manipulation of specifically defined variables known to affect attentional processing.

The BFCS is comprised of a group of magnocellular, ACh-utilizing neurons distributed among heterogeneous anatomical structures along the ventral aspect of the mammalian forebrain. This system includes a loosely-clustered arrangement of cholinergic neurons located in the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (nBM) and rostrally contiguous ventral pallidum/substantia innominata (VP/SI), termed the Ch4 subgroup by Mesulam and colleagues [82,84]. These neurons project diffusely to all layers and areas of the neocortical mantle [10], where the primary physiological effect of ACh is to modulate the response of pyramidal cells to other—particularly glutamatergic—cortical input [74,85]. This innervation of the neocortex by basal forebrain cholinergic neurons is an important mediator of cortical activation in support of cognitive function.

The available evidence suggests that multiple aspects of attention are dependent upon cortical cholinergic inputs arising from the basal forebrain. Pharmacological manipulations of cholinergic receptors in humans are known to affect attentional performance [7]. In animals, lesion studies, particularly those employing the immunotoxin, 192 IgG-saporin, which selectively destroys cortically projecting basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in rats, have been useful for demonstrating the necessity of the BFCS for attention [77]. For example, accuracy of visual signal detection is decreased in attention-demanding tasks following loss of basal forebrain corticopetal cholinergic neurons [75,78]. Performance in divided attention paradigms is also disrupted following intrabasalis infusions of 192 IgG-saporin [134]. Moreover, cortical acetylcholine release is elevated during attentional task performance compared with control tasks that limit explicit attentional demands, but that do require similar levels of motoric functioning and that provide similar reinforcement schedules as the attention-demanding task [3,29,98]. Thus, the actions of orexins within the basal forebrain on attention can potentially be dissociated with other nonspecific task variables.

Anatomical substrates of orexin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system

A series of important primate studies from the 1970’s showed that (putatively cholinergic) basal forebrain neurons respond to food-related visual stimuli only when the animal is hungry [21,89,109,110]. These observations provided a clear demonstration that the interoceptive state of an animal modulates the response to sensory cues related to physiological status. In other words, homeostatic drive modulates the appetitive salience of a stimulus and the response of neural circuitry underlying attention to that stimulus. While this may seem intuitive, thorough anatomical and phenotypical descriptions of the neural substrates of this relationship have not been forthcoming. What are the neuroanatomical substrates by which information related to physiological status is relayed to neuromodulatory systems involved in attention?

The primary central structure mediating the brain’s detection of—and response to—physiological cues from the periphery is the hypothalamus. While the lateral hypothalamus has been classically conceptualized as a “feeding center”, it is also part of the posterior hypothalamus, a major component of the mammalian arousal system [60,69,108,127]. Thus, this hypothalamic area may be involved in supporting the autonomic and behavioral responses necessary for homeostatic regulation. Because attention, or the ability to detect and select relevant stimuli, requires a generalized state of physiological readiness, i.e., arousal [106], the afferent regulation of the BFCS by brain regions active in the establishment or maintenance or arousal is of major significance.

Projections from the lateral hypothalamus to the cholinergic basal forebrain have been well-documented and have been hypothesized to relay interoceptive information to this area [26,146]. However, phenotypic and functional descriptions of the pathways by which the lateral hypothalamus relays information to rostral brain regions involved in cognitive function have only begun to be elucidated in recent years. As more is learned about the phenotype and function of ascending hypothalamic projections to areas such as the basal forebrain, a greater appreciation of the role played by these pathways in cognitive and behavioral correlates of age-related hypothalamic dysfunction is likely to emerge.

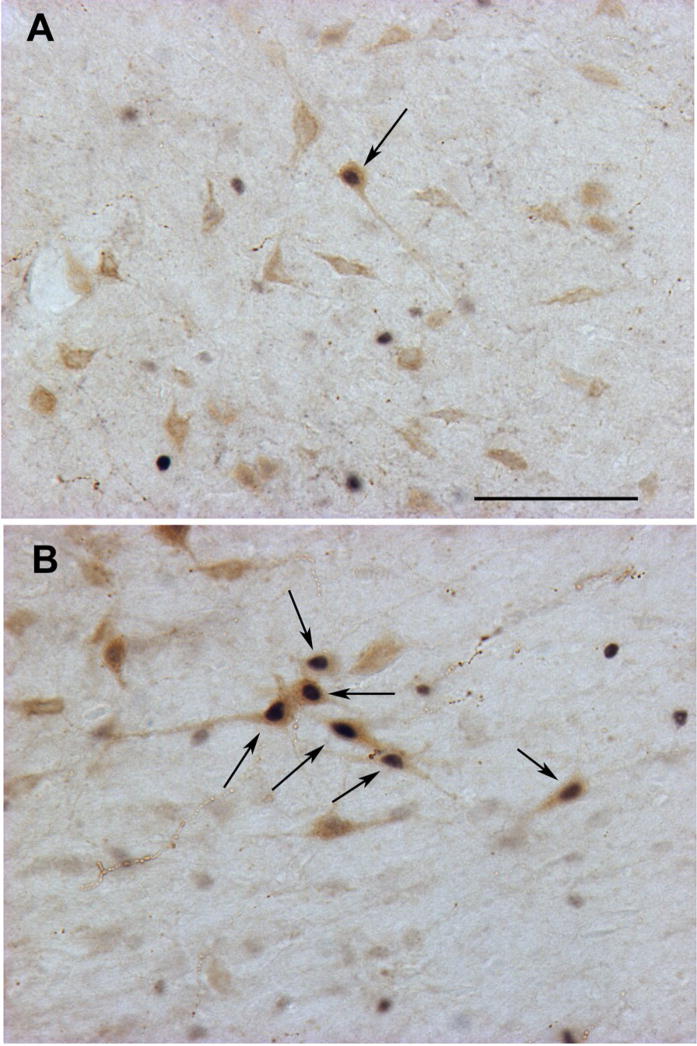

In recent years a clear anatomical substrate for interactions between orexin neurons and the BFCS has been documented. Hypothalamic projections to cholinergic parts of the basal forebrain were originally described as originating in the far-lateral and medial parts of the lateral hypothalamus [26], a pattern that roughly corresponds to the location of orexin neurons. Indeed, orexin-immunoreactive fibers in the rat distribute widely to various basal forebrain structures [28,30,103]; included among these basal forebrain targets is the substantia innominata, which receives a predominantly ipsilateral orexin input [38]. Because cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain are not confined to a single, well-circumscribed nucleus, it was important for these orexin inputs to be further characterized specifically with regard to the phenotype of their post-synaptic targets. Orexin-immunoreactive fibers in the substantia innominata and contiguous ventral pallidum make apparent appositional contacts on ChAT-positive, as well as parvalbumin-positive, cells [43] (see also Figure 1), suggesting the potential for a direct influence of orexins over corticopetal cholinergic and GABAergic projections. While the existence of these postulated monosynaptic connections between orexin fibers and cholinergic neurons awaits ultrastructural confirmation, a combined electron and light microscopic study in the brainstem dorsal raphe nucleus has shown that orexin immunoreactive varicosities observed at the light microscopic level have the ultrastructural appearance of presynaptic axon terminals, with numerous dense core vesicles [138]. Thus, these varicosities likely represent functional orexin synapses on and around cholinergic somata and perikarya as has already been described for septohippocampal cholinergic neurons [142]. In addition, retrograde tracer deposits in the basal forebrain label many non-orexin neurons in the area of the lateral hypothalamus [100]; although the phenotype of these basal forebrain-projecting, non-orexin neurons remains to be determined, they may represent an additional source of hypothalamic regulation of the BFCS in the context of homeostatic function. However, the available anatomical data clearly demonstrate that orexin neurons contribute substantially to the previously-recognized projection from the lateral hypothalamus to the cholinergic basal forebrain [26], implicating the basal forebrain as an integral component of a distributed network that underlies orexin effects on arousal and attention [38].

Figure 1. Examples of orexin innervation of cholinergic and GABAergic neurons of the basal forebrain.

All photomicrographs were taken from the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata region of the adult (age 3 months) rat basal forebrain (D), following dual-color immunoperoxidase histochemistry using previously described methods [41,45]. A–C. Double-labeling for ChAT (light brown cell body) and orexin A (black fibers). Arrows indicate points of putative appositional contact between orexin fibers and a cholinergic neuron. Scale bar represents approximately 25 μm. B and C show different focal planes from the same region, indicating multiple putative z-plane contacts on the proximal dendrite (B) and soma (C) of the same neuron. E. Double-labeling for the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (light brown cell bodies), which marks a subset of GABAergic corticopetal basal forebrain neurons, and orexin A (black fibers). Again, orexin fibers are found in high abundance in this region of the basal forebrain, including on and around GABAergic neurons.

Orexin regulation of basal forebrain cholinergic system activity

Functional descriptions of the importance of orexin-BFCS interactions have derived from electrophysiological, neurochemical and behavioral studies. Although brain orexin levels in general tend to be greatest during wakeful periods, microdialysis across the sleep-wake cycle reveals significant increases in basal forebrain release of OxA during paradoxical, or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [63]. Electrophysiological data suggest that this may reflect burst discharge of orexin neurons during phasic REM as these cells are largely silent during tonic REM [87], although given the different time scales of microdialysis and juxtacellular recordings, this relationship between burst discharge and orexin release remains speculative. REM sleep is also associated with activation of corticopetal cholinergic neurons [60,128], suggesting a potential role for orexins in this phenomenon. Clearly, however, Fos expression and in vivo electrophysiological data both indicate a high level of orexin neuron activity during transitions to wakefulness [39,68]. Similarly, intrabasalis administration of OxA via reverse microdialysis or direct intracranial infusion increases behavioral indices of wakefulness [37,131]. Intrabasalis administration of orexin A produces robust increases in ACh release within the PFC [43] and amplifies the effects of pedunculopontine tegmentum stimulation on electroencephalograph desynchrony [35], suggesting that orexins may increase arousal via complementary and synergistic effects on both basal forebrain and brainstem cholinergic systems [8,135].

Orexin A activates both types of orexin receptors with roughly equal affinity; hence, effects of this peptide on the basal forebrain cholinergic system do not point to a specific receptor subtype. Furthermore, both Ox1R and Ox2R appear to be expressed in parts of the basal forebrain that include corticopetal cholinergic neurons [54,62,72] and electrophysiological and neurochemical data are consistent with a role for both Ox1R and Ox2R in activation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system. In vitro electrophysiological data indicate that OxB is at least as potent as OxA at exciting basal forebrain cholinergic cells, suggesting primarily an Ox2R-mediated effect [36]. These observations place the basal forebrain cholinergic system within the distributed network underlying the effects of orexins on arousal and wakefulness, as the narcoleptic phenotype associated with loss of orexin neurons or peptides in humans and mice is largely recapitulated in narcoleptic canines with a spontaneously-occurring loss of function mutation in Ox2R [70]. However, other studies have suggested that the effects of basal forebrain orexin administration on wakefulness are largely Ox1R-mediated. Lateral ventricular administration of OxA, for example, is more effective than OxB at increasing electroencephalographic, electromyographic and behavioral indices of wakefulness, and these effects are recapitulated with direct intrabasalis administration of OxA [37]. Also, in anesthetized rats, intrabasalis administration of OxA is more effective than OxB at increasing somatosensory cortical ACh release and inducing an arousal-like electroencephalograph pattern [35]. Our studies on the effects of orexins on cortical cholinergic transmission are also consistent with an Ox1R mechanism, as stimulated cortical ACh release under conditions tied to feeding-related arousal is largely blocked by the Ox1R antagonist, SB-334867, [45]. In addition to a primary effect mediated by direct activation of orexin receptors on cholinergic neurons, this may reflect the ability of OxA to increase glutamate release within the basal forebrain [42]. While ultrastructural studies definitively demonstrating the presence of presynaptic orexin receptors on glutamatergic terminals in the basal forebrain have not been reported, these receptors are expressed in sources of presumptive glutamatergic inputs to the basal forebrain, including the prefrontal and insular cortices [54,72]. Ox1R is also expressed in orexin neurons themselves [5], at least some of which colocalize glutamate [111,133]. Finally, several electrophysiological studies have suggested the ability of orexin to increase presynaptic glutamate release in other orexin-receptive brain regions, including the PFC[67], VTA [12] and preoptic area [64]. Collectively, these studies support the hypothesis that—in addition to direct effects—orexins may excite basal forebrain cholinergic neurons via presynaptic glutamatergic mechanisms.

The current data do not allow for definitive conclusions regarding which of the orexin receptor subtypes is most heavily involved in activation of the BFCS. Indeed, the two receptors may play different, but complementary roles in response to varying types of homeostatic challenges. Ultrastructural studies documenting the precise pre- and post-synaptic localization of Ox1R and Ox2R within the basal forebrain as well as commercial availability of additional selective agonists and antagonists of these receptors will provide much-needed anatomical and pharmacological data concerning the mechanisms and functional contexts underlying orexin effects on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons.

Physiological determinants of orexin-ACh interactions

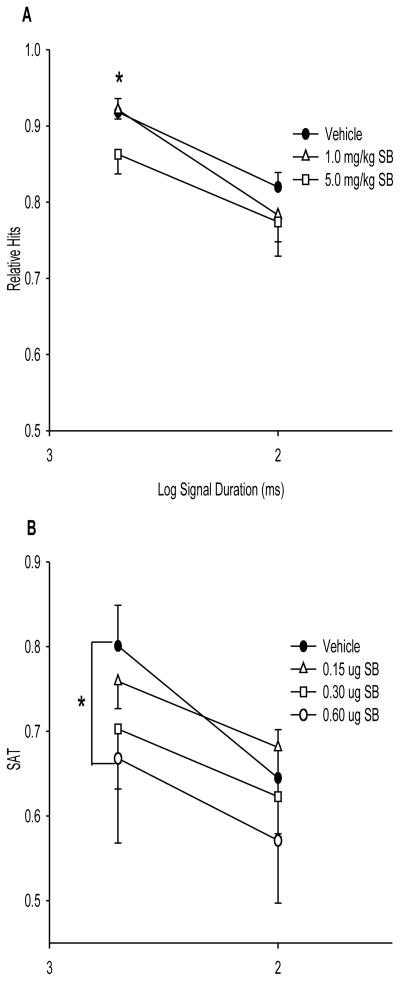

Given the integrative role of orexin neurons, characterizing the specific contribution of these peptides to activation of the BFCS in response to cues related to physiological homeostasis is important. Orexin neurons are sensitive to a number of peripherally-derived circulating factors whose fluctuations provide information about homeostatic status, including leptin, ghrelin and glucose [18,19,50,113]. Food deprivation increases expression of orexin peptides and/or receptors [66,71] and orexins are important for food anticipatory-related arousal in fasted animals [1,86], strongly implicating the orexin system in cholinergic activation by stimuli of homeostatic relevance. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have shown that the normal, robust, cholinergic response to palatable food reward in food-restricted rats is dramatically blunted by pretreatment with the Ox1R antagonist SB-334867 or by immunotoxic lesions that destroy orexin neurons [45]. Importantly, the SB-334867 effects were recapitulated by intrabasalis administration of the drug, indicating that orexin regulation of the BFCS under these conditions does not merely reflect transsynaptic effects mediated by brainstem arousal systems. Furthermore, behaviorally, Ox1R antagonism is associated with increased latency to approach and consume a food reward. It has been suggested that orexin effects on feeding are secondary to their role in regulating arousal threshold [126]. A cognitive correlate to this hypothesis is that orexins—via interactions with areas such as the BFCS—are important for attention to both the interoceptive components of a physiological challenge (“How do I feel?”) and the detection and processing of exteroceptive stimuli related to interoceptive state (“Which sensory cues in my environment are salient?”). Accordingly, ascending inputs to the orexin neurons suggest substrates for regulation beyond those limited to metabolic cues, but also derive from brainstem regions that may convey information regarding arousal, pain and visceral status [115,145]. Psychological stress states, such as those that accompany fear and anxiety may represent an additional interoceptive cue whose autonomic, behavioral and cognitive correlates may depend in part on the orexin system [67,73]. Neurotoxic lesions of the perifornical hypothalamus, for example, abolish the cardiovascular and behavioral components of conditioned fear [47]. Interestingly, our recent preliminary data indicate that orexin neurons are also activated by the anxiogenic benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist FG-7142 (Figure 2), whose autonomic and cognitive effects are mediated in part via the basal forebrain cholinergic system [9,88]. Orexin neurons, then, are strategically located to regulate the activity of the BFCS in response to a wide variety of interoceptive cues. Disruptions in these interactions may contribute to attentional dysfunction in a variety of neuropsychiatric conditions, as discussed below.

Figure 2. Activation of orexin neurons by FG-7142.

Adult male rats were treated acutely with the anxiogenic benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist FG-7142 (8.0 mg/kg; i.p.) or vehicle and sacrificed two hours later. Brains were processed for double-label immunohistochemistry for Fos (black nuclei) and orexin (light brown cytoplasmic staining) using previously-described methods [40,100]. Few double-labeled cells are seen following vehicle treatment (A). FG-7142 treatment (B) produced a robust activation of perifornical orexin neurons as seen in this cluster of double-labeled cells (arrows). Scale bar represents approximately 100 μm.

Orexin regulation of attention

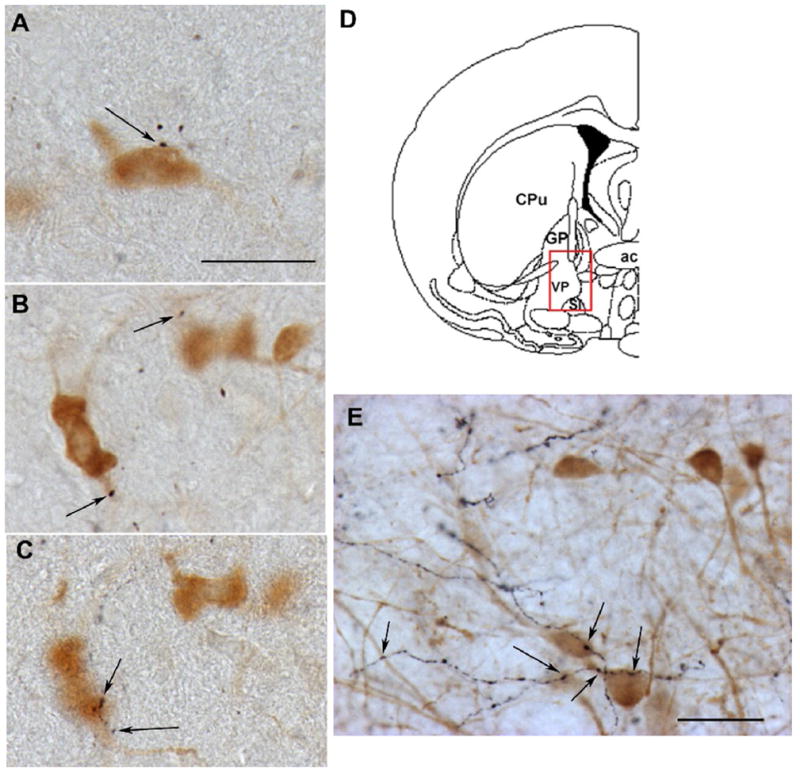

Alterations of attentional processing related to disruptions of cholinergic functioning have been associated with numerous neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and drug addiction [16,44,121]. Attentional dysfunction may lead to disruptions of working memory or bias processing for specific environmental cues [120,122]. Thus, disrupted attention may contribute to other symptoms associated with some disorders. We have reported that systemic administration of the OX1R antagonist, SB-334867, decreases signal detection in a two-lever attention task requiring discrimination of visual signals from trials with no signal presentation [14] (See also Figure 3). A similar pattern of impairment, a decrease in signal detection, has been reported following loss of basal forebrain corticopetal cholinergic neurons [76,78]. When SB-334867 was administered directly into the basal forebrain before performance in this task, we observed decreases in an overall measure of accuracy that takes into account performance on trials with signals and without signal presentation. Thus, intrabasalis SB-334867 also produced a marginal decrease in accuracy on no signal trials. Ibotenic acid-induced basal forebrain lesions, which produce relatively greater damage to non-cholinergic basal forebrain neurons compared to cholinergic neurons, also decrease accuracy in this task on trials when no signal is presented [20]. Thus, we concluded that orexinergic inputs onto cholinergic and non-cholinergic basal forebrain neurons represent an important system for regulating attentional processing. Interactions between cortical ACh and GABA have been discussed, but remain poorly understood [117]. Prefrontal cortical inputs to the basal forebrain make synapses onto neurons that putatively release GABA [48,147]. Collectively, the available evidence suggests that orexinergic inputs can modulate basal forebrain cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurons, which may, in turn, affect prefrontal cortical processing. Dysregulation of orexin inputs to the basal forebrain may contribute to attentional deficits in some disorders, as discussed in more detail below. Orexins have also been implicated in learning and memory, with orexin A enhancing performance in active and passive avoidance procedures [58,129]. Cortical cholinergic inputs have been hypothesized to contribute to learning and memory, particularly in tasks that place high demands on attentional processing[118]. Thus, alterations in attention associated with pharmacological manipulation of orexin receptors may contribute to some of the effects of orexins on learning and memory [14,118]. However, caution is warranted in these conclusions as the effects of orexin A or B administration on performance in attention-demanding tasks has not been reported.

Figure 3. Effects of orexin-1 receptor blockade on attentional performance.

The figure depicts the significant effects of systemic (A) or intrabasalis (B) SB-334867 in an attention-demanding task that required discrimination of brief visual signals from trials with no signal presentation. Systemic SB-334867 (5.0 mg/kg; i.p.) significantly decreased signal detection following the 500-ms signal (relative hits; denoted by the asterisk), effects similar to those observed following loss of basal forebrain corticopetal cholinergic inputs [76,79]. Intrabasalis SB-334867 (60 μg) decreased accuracy on a sustained attention (SAT) measure, that takes into account accuracy on trials with and without signal presentation (denoted by the asterisk). This decrease in overall accuracy may reflect that SB-334867 also affected noncholinergic basal forebrain corticopetal cholinergic neurons [20,117]. The figure is modified from Boschen et al. [14]. Error bars represent SEMs.

Narcolepsy

Post-mortem studies have clearly demonstrated that human narcolepsy is associated with a loss of orexin peptides [95,102,132]. Similarly, the spontaneously-occurring form of canine narcolepsy is associated with a loss-of-function mutation in Ox2R [70] and orexin knockout mice display a narcoleptic phenotype [24]. Interestingly, narcoleptic patients demonstrate attentional deficits even during periods of normal wakefulness [93,105], consistent with a role for the orexin system in some aspects of cognition. Canine narcolepsy is also associated with neurodegeneration in parts of the basal forebrain [125], suggesting that a primary deficit in orexin signaling might contribute to postsynaptic degeneration and impaired ACh-dependent cognitive function.

Drug addiction and relapse

A clear role is emerging for the orexin system in responses to drugs of abuse. Orexin neurons are activated by a variety of psychostimulant drugs, including nicotine [101], amphetamine [40], methamphetamine [39], and the wake-promoting drug modafinil [123]. Morphine-conditioned place preference is associated with activation of lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in a manner that suggests the involvement of this subgroup of orexin neurons in reward [51,52]. Orexin transmission in the VTA appears to play an essential role in the physiological and behavioral correlates of repeated cocaine administration [13]. Furthermore, an Ox1R antagonist has recently been shown to attenuate self-administration of nicotine in rats, perhaps via circuitry involving the insular cortex [55]. What role might orexin actions in the basal forebrain cholinergic system play in these phenomena?

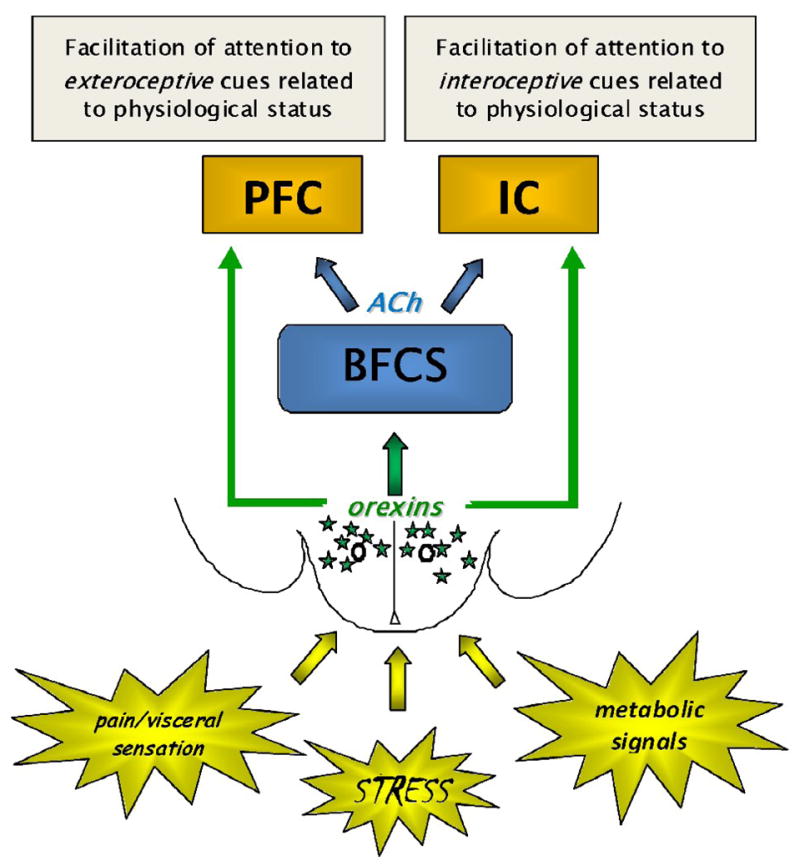

We have recently shown that acute nicotine administration increases expression of the immediate-early gene product, Fos, in orexin neurons that project to the basal forebrain and paraventricular nucleus of the dorsal thalamus [100]. This suggests that ascending orexin projections may be important for coordinating the arousal and attentional correlates of nicotine administration. Repeated nicotine or amphetamine administration sensitizes cortical ACh release and the behavioral correlates of this neurochemical response suggest that this may underlie alterations of attentional processing [4,33,94]. Similarly, the ability of insular cortex SB-334867 to block nicotine self-administration [55] is consistent with clinical data pointing to an important role of the insula in nicotine addiction [92] as well as the hypothesized role of this cortical region in interoception [25]. In addition to serving as a site of convergence of cholinergic and orexin inputs, the insular cortex is a major source of cortical projections back to the basal forebrain in primates and rodents [22,81,147]. Collectively, this suggests that orexins may coordinate attention to interoceptive and exteroceptive cues related to psychostimulant drugs of abuse (Figure 4). Interestingly, orexin neurons appear to receive a reciprocal innervation from cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain [115], and ACh depolarizes orexin neurons [144]. Recent studies in our lab demonstrate that nicotine increases ACh release in the LH/PFA [99], suggesting that—in addition to the effect of orexins on the BFCS—cholinergic inputs to the hypothalamus may recruit orexin neurons in a “top-down” fashion, allowing for enhancement of general arousal in response to the detection of salient external cues.

Figure 4. Hypothetical summary model of orexin regulation of cholinergic projections to prefrontal (PFC) and insular (IC) cortices, based on known anatomical relationships.

ACh neurons from the basal forebrain cholinergic system (BFCS) have widespread cortical projections, including to PFC and IC. The involvement of the PFC in executive function and the putative role of the IC as “interoceptive cortex” suggests that the BFCS may influence exteroceptive and interoceptive attention via projections to these areas, respectively. Orexin neurons of the lateral hypothalamus and perifornical area (green stars), as integral components of the hypothalamic circuitry responsive to physiological signals, may allow for coordinated activation of rostral attentional circuitry, ultimately allowing for biased allocation of attentional resources toward stimuli related to physiological status. Alterations in these interactions may contribute to a number of neuropsychiatric conditions in which individual components of these pathways have been implicated, including drug addiction or relapse and the anorexia of aging.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the orexin system plays a crucial role in the neuroplasticity that underlies several aspects of repeated psychostimulant administration in animal models [11,13,15,137]. The absence of orexin neurons in narcoleptic patients with cataplexy has been suggested to underlie anecdotal reports of the reduced susceptibility of these patients to stimulant abuse and addiction [148]. Psychostimulant abuse can produce “hyper-attentional” impairments—defined as the compulsive processing of drug-related cues to the exclusion of other environmental cues—that may predispose to relapse by pathological processing of drug-related stimuli [61]. These impairments have been hypothesized to be mediated through the BFCS, suggesting a possible role for orexin-ACh interactions [94,120,141]. Thus, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that orexin regulation of basal forebrain cholinergic inputs to cortical areas such as the PFC and insula may enhance attentional processing of external, drug-related cues and internal cues related to the aversive state that accompanies, for example, withdrawal.

Aging

There is little evidence for frank degeneration, in the form of substantial cell loss, of the orexin system solely as a function of age in humans or animal models. However, a compelling body of data is beginning to accumulate suggesting that aging may be associated with a decline in expression of orexins or their receptors as well as decreased innervation of certain target structures. For example, aging is associated with decreased Ox2R expression in several brain regions in mice [130]. Aging has also been shown to decrease levels of both OxA and OxB, as well as their common precursor, preproorexin, in the rat brain [104]. Old rats have decreased cerebrospinal fluid orexin levels across the sleep-wake cycle [34]. Altered innervation of brainstem structures, including a decrease in orexin-immunoreactive fibers in the locus coeruleus, has been reported [149]. Similarly, our own preliminary data indicate that aged rats have reduced numbers of putative appositional contacts on and around ChAT-positive cell bodies in the basal forebrain [46]. What might be the implications of age-related changes in the orexin system for basal forebrain cholinergic function?

An early and consistent feature of age-related changes in cognitive function, ranging from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease, is a decline in attentional capacity [96,122,124]. These deficits likely reflect alterations in several interacting neurotransmitter systems, including a prominent role for the corticopetal cholinergic system [53,91,107,116,139]. However, while severe and late stage dementia is clearly marked by a loss of cholinergic neurons and markers of cholinergic activity [90,112,140], frank loss of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons does not consistently appear to be the earliest or most pronounced neuropathological alteration in these disorders or in animal models of aging [27,65,80,83]. This suggests that age-related decline in certain cognitive functions putatively mediated by the cholinergic system may stem, in part, from a failure of normal afferent regulation of the BFCS. Alterations in hypothalamic, including orexin, modulation of the cholinergic system is likely to contribute to these changes. Interestingly, recent evidence shows that changes in homeostatic measures such as food intake and body weight may precede, and indeed predict, subsequent cognitive decline; in some cases, these studies reveal an association between Alzheimer’s disease and unexplained weight loss as many as 10 years prior to the onset of frank dementia. [17,49,59]. The factors underlying age-related changes in homeostatic regulation and cognition are assuredly heterogeneous and multifactorial [23,57,143]. However, a failure of brain regions involved in homeostatic regulation (e.g., the orexin system) to activate other brain regions (e.g., the BFCS) that mediate the appropriate behavioral and cognitive responses to homeostatic challenges such as food or water deprivation may mechanistically link these disparate phenomena.

Conclusion

Hypothalamic regulation of the BFCS represents a pathway by which interoceptive information gains access to attentional mechanisms. Orexin neurons are quantitatively and functionally significant contributors to this pathway. Dysfunction in orexin-acetylcholine interactions may play a role in the arousal and attentional deficits that accompany neurodegenerative conditions as diverse as drug addiction and age-related cognitive decline.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Federation for Aging Research (JF) and the National Institutes of Health R01AG030646 (JF and JAB).

Footnotes

Gary Aston-Jones and Rita Valentino, Guest Editors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akiyama M, Yuasa T, Hayasaka N, Horikawa K, Sakurai T, Shibata S. Reduced food anticipatory activity in genetically orexin (hypocretin) neuron-ablated mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:3054–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammoun S, Holmqvist T, Shariatmadari R, Oonk HB, Detheux M, Parmentier M, Akerman KE, Kukkonen JP. Distinct recognition of OX1 and OX2 receptors by orexin peptides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:507–14. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold H, Burk J, Hodgson E, Sarter M, Bruno J. Differential cortical acetylcholine release in rats performing a sustained attention task versus behavioral control tasks that do not explicitly tax attention. Neuroscience. 2002;114:451. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold HM, Nelson CL, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Sensitization of cortical acetylcholine release by repeated administration of nicotine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:346–58. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backberg M, Hervieu G, Wilson S, Meister B. Orexin receptor-1 (OX-R1) immunoreactivity in chemically identified neurons of the hypothalamus: focus on orexin targets involved in control of food and water intake. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:315–28. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldo BA, Daniel RA, Berridge CW, Kelley AE. Overlapping distributions of orexin/hypocretin- and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase immunoreactive fibers in rat brain regions mediating arousal, motivation, and stress. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:220–37. doi: 10.1002/cne.10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentley P, Husain M, Dolan RJ. Effects of cholinergic enhancement on visual stimulation, spatial attention, and spatial working memory. Neuron. 2004;41:969–82. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard R, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Hypocretin (orexin) receptor subtypes differentially enhance acetylcholine release and activate g protein subtypes in rat pontine reticular formation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:163–71. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berntson GG, Hart S, Ruland S, Sarter M. A central cholinergic link in the cardiovascular effects of the benzodiazepine receptor partial inverse agonist FG 7142. Behav Brain Res. 1996;74:91–103. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bigl V, Woolf NJ, Butcher LL. Cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain to frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and cingulate cortices: a combined fluorescent tracer and acetylcholinesterase analysis. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8:727–49. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonci A, Borgland S. Role of orexin/hypocretin and CRF in the formation of drug-dependent synaptic plasticity in the mesolimbic system. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgland SL, Storm E, Bonci A. Orexin B/hypocretin 2 increases glutamatergic transmission to ventral tegmental area neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borgland SL, Taha SA, Sarti F, Fields HL, Bonci A. Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron. 2006;49:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boschen KE, Fadel JR, Burk JA. Systemic and intrabasalis administration of the orexin-1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867, disrupts attentional performance in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1596-2. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, de Lecea L. Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brousseau G, Rourke BP, Burke B. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and Alzheimer’s disease subtypes: an alternate hypothesis to global cognitive enhancement. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:546–54. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Shah RC, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Change in body mass index and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:892–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176061.33817.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdakov D, Gonzalez JA. Physiological functions of glucose-inhibited neurones. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;195:71–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burdakov D, Jensen LT, Alexopoulos H, Williams RH, Fearon IM, O’Kelly I, Gerasimenko O, Fugger L, Verkhratsky A. Tandem-pore K+ channels mediate inhibition of orexin neurons by glucose. Neuron. 2006;50:711–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burk JA, Sarter M. Dissociation between the attentional functions mediated via basal forebrain cholinergic and GABAergic neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;105:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton MJ, Rolls ET, Mora F. Effects of hunger on the responses of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus to the sight and taste of food. Exp Neurol. 1976;51:668–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnes KM, Fuller TA, Price JL. Sources of presumptive glutamatergic/aspartatergic afferents to the magnocellular basal forebrain in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:824–52. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman IM, MacIntosh CG, Morley JE, Horowitz M. The anorexia of ageing. Biogerontology. 2002;3:67–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1015211530695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cullinan WE, Zaborszky L. Organization of ascending hypothalamic projections to the rostral forebrain with special reference to the innervation of cholinergic projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1991;306:631–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.903060408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings JL, Benson DF. The role of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in dementia: review and reconsideration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1987;1:128–55. doi: 10.1097/00002093-198701030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutler DJ, Morris R, Sheridhar V, Wattam TA, Holmes S, Patel S, Arch JR, Wilson S, Buckingham RE, Evans ML, Leslie RA, Williams G. Differential distribution of orexin-A and orexin-B immunoreactivity in the rat brain and spinal cord. Peptides. 1999;20:1455–70. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalley JW, McGaughy J, O’Connell MT, Cardinal RN, Levita L, Robbins TW. Distinct changes in cortical acetylcholine and noradrenaline efflux during contingent and noncontingent performance of a visual attentional task. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4908–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04908.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Date Y, Ueta Y, Yamashita H, Yamaguchi H, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakazato M. Orexins, orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, interact with autonomic, neuroendocrine and neuroregulatory systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, Fabre V. Hypocretins/orexins as integrators of physiological information: lessons from mutant animals. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:85–95. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deller T, Sarter M. Effects of repeated administration of amphetamine on behavioral vigilance: evidence for “sensitized” attentional impairments. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:410–4. doi: 10.1007/s002130050637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desarnaud F, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Lin L, Xu M, Gerashchenko D, Shiromani SN, Nishino S, Mignot E, Shiromani PJ. The diurnal rhythm of hypocretin in young and old F344 rats. Sleep. 2004;27:851–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong HL, Fukuda S, Murata E, Zhu Z, Higuchi T. Orexins increase cortical acetylcholine release and electroencephalographic activation through orexin-1 receptor in the rat basal forebrain during isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1023–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eggermann E, Serafin M, Bayer L, Machard D, Saint-Mleux B, Jones BE, Muhlethaler M. Orexins/hypocretins excite basal forebrain cholinergic neurones. Neuroscience. 2001;108:177–81. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espana RA, Baldo BA, Kelley AE, Berridge CW. Wake-promoting and sleep-suppressing actions of hypocretin (orexin): basal forebrain sites of action. Neuroscience. 2001;106:699–715. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espana RA, Reis KM, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW. Organization of hypocretin/orexin efferents to locus coeruleus and basal forebrain arousal-related structures. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:160–78. doi: 10.1002/cne.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1656–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fadel J, Bubser M, Deutch AY. Differential activation of orexin neurons by antipsychotic drugs associated with weight gain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6742–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06742.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fadel J, Deutch AY. Anatomical substrates of orexin-dopamine interactions: lateral hypothalamic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2002;111:379–87. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadel J, Frederick-Duus D. Orexin/hypocretin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system: Insights from in vivo microdialysis studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fadel J, Pasumarthi R, Reznikov LR. Stimulation of cortical acetylcholine release by orexin A. Neuroscience. 2005;130:541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: a review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frederick-Duus D, Guyton MF, Fadel J. Food-elicited increases in cortical acetylcholine release require orexin transmission. Neuroscience. 2007;149:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frederick-Duus D, Wilson SP, Fadel J. Modulation of the orexin/hypocretin system in young and aged rats using lentivirus-mediated gene transfer: effects on cortical acetylcholine release. Soc Neurosci Abst. 2008;38:592.7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furlong T, Carrive P. Neurotoxic lesions centered on the perifornical hypothalamus abolish the cardiovascular and behavioral responses of conditioned fear to context but not of restraint. Brain Res. 2007;1128:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gritti I, Mainville L, Mancia M, Jones BE. GABAergic and other noncholinergic basal forebrain neurons, together with cholinergic neurons, project to the mesocortex and isocortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;383:163–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grundman M. Weight loss in the elderly may be a sign of impending dementia. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:20–2. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hakansson M, de Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, Yanagisawa M, Meister B. Leptin receptor- and STAT3-immunoreactivities in hypocretin/orexin neurones of the lateral hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:653–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Randall-Thompson JF, Aston-Jones G. Lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons are critically involved in learning to associate an environment with morphine reward. Behav Brain Res. 2007;183:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasselmo ME, McGaughy J. High acetylcholine levels set circuit dynamics for attention and encoding and low acetylcholine levels set dynamics for consolidation. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:207–31. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hervieu GJ, Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Roberts JC, Leslie RA. Gene expression and protein distribution of the orexin-1 receptor in the rat brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;103:777–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hollander JA, Lu Q, Cameron MD, Kamenecka TM, Kenny PJ. Insular hypocretin transmission regulates nicotine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19480–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808023105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horvath TL, Peyron C, Diano S, Ivanov A, Aston-Jones G, Kilduff TS, van Den Pol AN. Hypocretin (orexin) activation and synaptic innervation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:145–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horwitz BA, Blanton CA, McDonald RB. Physiologic determinants of the anorexia of aging: insights from animal studies. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:417–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.120301.071049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaeger LB, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of orexin-A on memory processing. Peptides. 2002;23:1683–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson DK, Wilkins CH, Morris JC. Accelerated weight loss may precede diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1312–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.9.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones BE. Arousal systems. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s438–51. doi: 10.2741/1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jovanovski D, Erb S, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficits in cocaine users: a quantitative review of the evidence. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:189–204. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kilduff TS, de Lecea L. Mapping of the mRNAs for the hypocretin/orexin and melanin-concentrating hormone receptors: networks of overlapping peptide systems. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:1–5. doi: 10.1002/cne.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Maidment N, Lam HA, Wu MF, John J, Peever J, Siegel JM. Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5282–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolaj M, Coderre E, Renaud LP. Orexin peptides enhance median preoptic nucleus neuronal excitability via postsynaptic membrane depolarization and enhancement of glutamatergic afferents. Neuroscience. 2008;155:1212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kurosawa M, Sato A, Sato Y. Well-maintained responses of acetylcholine release and blood flow in the cerebral cortex to focal electrical stimulation of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in aged rats. Neurosci Lett. 1989;100:198–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90684-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kurose T, Ueta Y, Yamamoto Y, Serino R, Ozaki Y, Saito J, Nagata S, Yamashita H. Effects of restricted feeding on the activity of hypothalamic Orexin (OX)-A containing neurons and OX2 receptor mRNA level in the paraventricular nucleus of rats. Regul Pept. 2002;104:145–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambe EK, Liu RJ, Aghajanian GK. Schizophrenia, hypocretin (orexin), and the thalamocortical activating system. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1284–90. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin JS, Sakai K, Vanni-Mercier G, Jouvet M. A critical role of the posterior hypothalamus in the mechanisms of wakefulness determined by microinjection of muscimol in freely moving cats. Brain Res. 1989;479:225–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91623-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu XY, Bagnol D, Burke S, Akil H, Watson SJ. Differential distribution and regulation of OX1 and OX2 orexin/hypocretin receptor messenger RNA in the brain upon fasting. Horm Behav. 2000;37:335–44. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mathew SJ, Price RB, Charney DS. Recent advances in the neurobiology of anxiety disorders: implications for novel therapeutics. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C:89–98. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCormick DA. Actions of acetylcholine in the cerebral cortex and thalamus and implications for function. Prog Brain Res. 1993;98:303–8. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McGaughy J, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Selective behavioral and neurochemical effects of cholinergic lesions produced by intrabasalis infusions of 192 IgG-saporin on attentional performance in a five-choice serial reaction time task. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1905–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McGaughy J, Decker MW, Sarter M. Enhancement of sustained attention performance by the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist ABT-418 in intact but not basal forebrain-lesioned rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:175–82. doi: 10.1007/s002130050991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McGaughy J, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, Sarter M. The role of cortical cholinergic afferent projections in cognition: impact of new selective immunotoxins. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115:251–63. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McGaughy J, Kaiser T, Sarter M. Behavioral vigilance following infusions of 192 IgG-saporin into the basal forebrain: selectivity of the behavioral impairment and relation to cortical AChE-positive fiber density. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:247–65. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McGaughy J, Sarter M. Sustained attention performance in rats with intracortical infusions of 192 IgG-saporin-induced cortical cholinergic deafferentation: effects of physostigmine and FG 7142. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1519–25. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mesulam M. The cholinergic lesion of Alzheimer’s disease: pivotal factor or side show? Learn Mem. 2004;11:43–9. doi: 10.1101/lm.69204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ. Neural inputs into the nucleus basalis of the substantia innominata (Ch4) in the rhesus monkey. Brain. 1984;107(Pt 1):253–74. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:170–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Rogers J. Age-related shrinkage of cortically projecting cholinergic neurons: a selective effect. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:31–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1-Ch6) Neuroscience. 1983;10:1185–201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Metherate R, Ashe JH. Nucleus basalis stimulation facilitates thalamocortical synaptic transmission in the rat auditory cortex. Synapse. 1993;14:132–43. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mieda M, Williams SC, Sinton CM, Richardson JA, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M. Orexin neurons function in an efferent pathway of a food-entrainable circadian oscillator in eliciting food-anticipatory activity and wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10493–501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3171-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mileykovskiy BY, Kiyashchenko LI, Siegel JM. Behavioral correlates of activity in identified hypocretin/orexin neurons. Neuron. 2005;46:787–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moore H, Stuckman S, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Stimulation of cortical acetylcholine efflux by FG 7142 measured with repeated microdialysis sampling. Synapse. 1995;21:324–31. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mora F, Rolls ET, Burton MJ. Modulation during learning of the responses of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus to the sight of food. Exp Neurol. 1976;53:508–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mufson EJ, Ma SY, Dills J, Cochran EJ, Leurgans S, Wuu J, Bennett DA, Jaffar S, Gilmor ML, Levey AI, Kordower JH. Loss of basal forebrain P75(NTR) immunoreactivity in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:136–53. doi: 10.1002/cne.10122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muir JL, Dunnett SB, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Attentional functions of the forebrain cholinergic systems: effects of intraventricular hemicholinium, physostigmine, basal forebrain lesions and intracortical grafts on a multiple-choice serial reaction time task. Exp Brain Res. 1992;89:611–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00229886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science. 2007;315:531–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1135926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Naumann A, Bellebaum C, Daum I. Cognitive deficits in narcolepsy. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:329–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nelson CL, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Repeated pretreatment with amphetamine sensitizes increases in cortical acetylcholine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:406–15. doi: 10.1007/s002130000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oken BS, Kishiyama SS, Kaye JA, Howieson DB. Attention deficit in Alzheimer’s disease is not simulated by an anticholinergic/antihistaminergic drug and is distinct from deficits in healthy aging. Neurology. 1994;44:657–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parasuraman R, Warm J, Sand Dember WN. Vigilance: taxonomy and utility. In: Mark LS, Warm JS, Huston RL, editors. Ergonomics and Human Factors. Springer Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Passetti F, Dalley JW, O’Connell MT, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Increased acetylcholine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex during performance of a visual attentional task. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3051–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pasumarthi R, Fadel J. Anatomical and neurochemical mediators of nicotine-induced activation of orexin neurons. Soc Neurosci Abst. 2006;36:369.22. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pasumarthi RK, Fadel J. Activation of orexin/hypocretin projections to basal forebrain and paraventricular thalamus by acute nicotine. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pasumarthi RK, Reznikov LR, Fadel J. Activation of orexin neurons by acute nicotine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;535:172–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;6:991–7. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Porkka-Heiskanen T, Alanko L, Kalinchuk A, Heiskanen S, Stenberg D. The effect of age on prepro-orexin gene expression and contents of orexin A and B in the rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rieger M, Mayer G, Gauggel S. Attention deficits in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep. 2003;26:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Robbins TW. Arousal systems and attentional processes. Biol Psychol. 1997;45:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(96)05222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Robbins TW, McAlonan G, Muir JL, Everitt BJ. Cognitive enhancers in theory and practice: studies of the cholinergic hypothesis of cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 1997;83:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)86040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Robinson TE, Whishaw IQ. Effects of posterior hypothalamic lesions on voluntary behavior and hippocampal electroencephalograms in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;86:768–86. doi: 10.1037/h0036397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rolls ET, Roper-Hall A, Sanghera MK. Activity of neurones in the substantia innominata and lateral hypothalamus during the initiation of feeding in the monkey [proceedings] J Physiol. 1977;272:24P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rolls ET, Sanghera MK, Roper-Hall A. The latency of activation of neurones in the lateral hypothalamus and substantia innominata during feeding in the monkey. Brain Res. 1979;164:121–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rosin DL, Weston MC, Sevigny CP, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Hypothalamic orexin (hypocretin) neurons express vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 or VGLUT2. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:593–603. doi: 10.1002/cne.10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rossor MN, Svendsen C, Hunt SP, Mountjoy CQ, Roth M, Iversen LL. The substantia innominata in Alzheimer’s disease: an histochemical and biochemical study of cholinergic marker enzymes. Neurosci Lett. 1982;28:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sakurai T. Roles of orexin/hypocretin in regulation of sleep/wakefulness and energy homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:231–41. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y, Kageyama H, Kunita S, Takahashi S, Goto K, Koyama Y, Shioda S, Yanagisawa M. Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron. 2005;46:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sarter M, Bruno JP. Cognitive functions of cortical acetylcholine: toward a unifying hypothesis. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:28–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sarter M, Bruno JP. The neglected constituent of the basal forebrain corticopetal projection system: GABAergic projections. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1867–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sarter M, Bruno JP, Givens B. Attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: what does it mean for learning and memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80:245–56. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sarter M, Givens B, Bruno JP. The cognitive neuroscience of sustained attention: where top-down meets bottom-up. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:146–60. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sarter M, Hasselmo ME, Bruno JP, Givens B. Unraveling the attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: interactions between signal-driven and cognitive modulation of signal detection. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sarter M, Nelson CL, Bruno JP. Cortical cholinergic transmission and cortical information processing in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:117–38. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sarter M, Turchi J. Age- and dementia-associated impairments in divided attention: psychological constructs, animal models, and underlying neuronal mechanisms. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;13:46–58. doi: 10.1159/000048633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Miller MS, Saper CB. Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8620–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08620.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Scinto LF, Daffner KR, Castro L, Weintraub S, Vavrik M, Mesulam MM. Impairment of spatially directed attention in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease as measured by eye movements. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:682–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540190062016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Siegel JM, Nienhuis R, Gulyani S, Ouyang S, Wu MF, Mignot E, Switzer RC, McMurry G, Cornford M. Neuronal degeneration in canine narcolepsy. J Neurosci. 1999;19:248–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sutcliffe JG, de Lecea L. The hypocretins: setting the arousal threshold. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:339–49. doi: 10.1038/nrn808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Swett CP, Hobson JA. The effects of posterior hypothalamic lesions on behavioral and electrographic manifestations of sleep and waking in cats. Arch Ital Biol. 1968;106:283–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Szyjmusiak R. Magnocellular nuclei of the basal forebrain: substrates of sleep and arousal regulation. Sleep. 1995;18:478–500. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Telegdy G, Adamik A. The action of orexin A on passive avoidance learning. Involvement of transmitters. Regul Pept. 2002;104:105–10. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Terao A, Apte-Deshpande A, Morairty S, Freund YR, Kilduff TS. Age-related decline in hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 messenger RNA levels in the mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:190–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Thakkar MM, Ramesh V, Strecker RE, McCarley RW. Microdialysis perfusion of orexin-A in the basal forebrain increases wakefulness in freely behaving rats. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:313–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:469–74. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Torrealba F, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB. Colocalization of orexin a and glutamate immunoreactivity in axon terminals in the tuberomammillary nucleus in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;119:1033–44. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Turchi J, Sarter M. Cortical acetylcholine and processing capacity: effects of cortical cholinergic deafferentation on crossmodal divided attention in rats. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 1997;6:147–58. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(97)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Vazquez J, Baghdoyan HA. Basal forebrain acetylcholine release during REM sleep is significantly greater than during waking. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R598–601. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.2.R598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Vittoz NM, Berridge CW. Hypocretin/Orexin Selectively Increases Dopamine Efflux within the Prefrontal Cortex: Involvement of the Ventral Tegmental Area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:384–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wang B, You ZB, Wise RA. Reinstatement of cocaine seeking by hypocretin (orexin) in the ventral tegmental area: independence from the local corticotropin-releasing factor network. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:857–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang QP, Guan JL, Matsuoka T, Hirayana Y, Shioda S. Electron microscopic examination of the orexin immunoreactivity in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Peptides. 2003;24:925–30. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Whitehouse PJ. Paying attention to acetylcholine: the key to wisdom and quality of life? Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:311–7. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Struble RG, Clark AW, Coyle JT, Delon MR. Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science. 1982;215:1237–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7058341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Williams MJ, Adinoff B. The role of acetylcholine in cocaine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1779–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wu M, Zaborszky L, Hajszan T, van den Pol AN, Alreja M. Hypocretin/orexin innervation and excitation of identified septohippocampal cholinergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3527–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5364-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wurtman JJ. The anorexia of aging: a problem not restricted to calorie intake. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:22–3. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yamanaka A, Muraki Y, Tsujino N, Goto K, Sakurai T. Regulation of orexin neurons by the monoaminergic and cholinergic systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:120–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yoshida K, McCormack S, Espana RA, Crocker A, Scammell TE. Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:845–61. doi: 10.1002/cne.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zaborszky L, Cullinan WE. Hypothalamic axons terminate on forebrain cholinergic neurons: an ultrastructural double-labeling study using PHA-L tracing and ChAT immunocytochemistry. Brain Res. 1989;479:177–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zaborszky L, Gaykema RP, Swanson DJ, Cullinan WE. Cortical input to the basal forebrain. Neuroscience. 1997;79:1051–78. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zeitzer JM, Nishino S, Mignot E. The neurobiology of hypocretins (orexins), narcolepsy and related therapeutic interventions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhang JH, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. Age-related changes in hypocretin (orexin) immunoreactivity in the cat brainstem. Brain Res. 2002;930:206–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]