Abstract

Few studies have investigated the absorption of phylloquinone (vitamin K1). We recruited twelve healthy, non-obese adults. On each study day, fasted subjects took a capsule containing 20 μg of 13C-labelled phylloquinone with one of three meals, defined as convenience, cosmopolitan and animal-oriented, in a three-way crossover design. The meals were formulated from the characteristics of clusters identified in dietary pattern analysis of data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey conducted in 2000-2001. Plasma phylloquinone concentration and isotopic enrichment were measured over 8 h. Significantly more phylloquinone tracer was absorbed when consumed with the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals than with the convenience meal (P = 0.001 and P = 0.035, respectively). Estimates of the relative availability of phylloquinone from the meals were: convenience meal = 1.00, cosmopolitan meal = 0.31, and animal-oriented meal = 0.23. Combining the tracer data with availability estimates for phylloquinone from the meals provides overall relative bioavailability values of convenience = 1.00, cosmopolitan = 0.46 and animal-oriented = 0.29. Stable isotopes provide a useful tool to investigate further the bioavailability of low doses of phylloquinone. Different meals can affect the absorption of free phylloquinone. The meal-based study design used in the current work provides an approach that reflects more closely the way foods are eaten in a free-living population.

Keywords: GC/MS, bioavailability, dietary pattern analysis

The earliest discovered biological action of vitamin K was the control of blood coagulation and consequently dietary guidelines in the UK[1] and elsewhere[2] are typically based on this function alone. However, it is now recognised that vitamin K has a much broader physiological role. Phylloquinone is the primary source of vitamin K in Western diets and average intakes in the UK are around 70 μg/d[3]. While these levels are sufficient for the maintenance of normal blood coagulation they may be insufficient for maximal vitamin D-dependent carboxylation of osteocalcin[4, 5] and matrix Gla protein (MGP)[6]. It has been suggested that higher phylloquinone intakes may be beneficial for bone health since they are associated with increased BMD[7] and lower fracture rates[8, 9], however the conclusions from observational studies are generally not supported by more recent intervention data [5, 10-12].

Where intakes may be marginal, and in order to set evidence-based dietary recommendations, it is important to understand the relationship between intake and nutrient status. For phylloquinone, the relationship between intake and plasma concentration, although significant, is not very strong[13]. An important consideration for the intake-status relationship is the bioavailability, an understanding of which is essential for the determination of the dietary quantity of a nutrient required to ensure adequate status and hence optimal health. In addition, information on phylloquinone bioavailability may be important in controlling coagulation in individuals on long-term anticoagulation treatment[14-16].

Phylloquinone is found in a wide-range of foods but vegetables provide over half of daily phylloquinone intake[3, 17]. Green leafy vegetables are considered the major source of phylloquinone contributing around 20% to daily intake. Some types of oils and fats also contain high amounts of phylloquinone[18] and due to their widespread use in many food products it is likely that these make an important contribution[3]. However, limited information is available on phylloquinone bioavailability from these different sources partly because of the difficulties associated with the analysis of phylloquinone. The majority of studies have compared absorption from different sources to standards, such as Konakion®[19-21] but the results are difficult to compare because of differences in study protocols. The studies have been limited to comparisons of bioavailability from foods given to small numbers of subjects, and often using relatively large vitamin doses. Studies comparing the relative bioavailability of phylloquinone from vegetable and oil sources have produced conflicting results[22, 23], most likely due to the different methods used to measure absorption.

The use of stable isotope labelled tracers potentially avoids some of these problems and provides a safe method of investigating absorption and bioavailability[24-26]. The use of intrinsically labelled vegetables has been investigated for the measurement of phylloquinone absorption[27-29] but this method of labelling is only suitable for single food items that are amenable to labelling in this way.

Bioavailability studies that focus on absorption from single food items may not reflect the true state of affairs in normal meal consumption since they do not take account of interactions between food components that may negate variation in bioavailability between single foods. Based on recent work in our laboratory[30, 31] we report here the development and application of a stable isotope-based method to measure phylloquinone absorption. Our initial aim was to determine the fraction of phylloquinone absorbed from test meals by using the labelled phylloquinone as a standard. However, because the meal significantly influenced absorption of the tracer we have presented the data as a meal effect, defined as the influence of the integrated meal on the absorption of free phylloquinone, and a matrix effect that describes the extraction efficiency or bioaccessability of phylloquinone from the meal components. In order to provide a objective basis for the meal composition used in our studies the test-meals were designed to reflect dietary clusters identified from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) of adults 2000–2001[32].

Methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy, non-smoking subjects were recruited (5 female and 7 male). The subjects were aged 31.3 ± 8.3 y (range 22 to 49 y), with a mean weight of 69.4 ± 9.3 kg, and BMI of 23.1 ± 2.3 kg/m2 (mean ± SD). Ethical permission for the study was obtained from the Suffolk Local Research Ethics Committee and informed, written consent was obtained from all subjects.

Stable isotope labelled phylloquinone

Methyl-13C labelled phylloquinone was synthesised by ARC Laboratories (Apeldoorn, The Netherlands). Isotopic purity, assessed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS) in our laboratory, was greater than 98%. The molecular weight of naturally occurring, unlabelled phylloquinone is 450 Da and for the labelled material 451 Da. A stock solution of 83.8 mg in 100 ml of ethanol was prepared, divided into aliquots and stored at −18°C. To prepare the dose for volunteers, 48 μl of the standard solution was added to 1 ml of groundnut oil to give a solution of 40 μg/ml. Ethanol was evaporated from the oil by heating at 35°C under N2 with a Pierce Reacti-therm heating block and Reacti-vap evaporator (Perbio Science, Erembodegem, Belgium). After vortexing for 1 min, 0.5 ml of groundnut oil containing 20 μg (44.4 nmol) of phylloquinone was transferred to a gelatine capsule (kindly provided by Capsugel, Colmar, France). Capsules were prepared fresh for each subject and stored, refrigerated, in amber medicine bottles.

Experimental protocol

Since recent phylloquinone intake has an effect on plasma phylloquinone concentration, prior to each study day, volunteers were supplied with a standard evening meal and asked not to eat anything else. The meal consisted of a pizza containing no ingredients known to be high in phylloquinone. On three occasions, at least two weeks apart, volunteers attended the volunteer suite at MRC Human Nutrition Research (HNR) after an overnight fast. An indwelling cannula was inserted into a forearm, and two baseline blood samples were collected into 7.5 ml EDTA S-monovettes® (Sarstedt Ltd, Leicester, UK). The volunteer then took the phylloquinone capsule (with water) immediately preceding consumption of one of three test meals. Previously prepared meals were defrosted overnight and reheated prior to consumption. In this three-period study, and to minimise sequence effects, subjects were randomised for the order they received the meals, with two subjects designated to each sequence. A snack (two slices of toast with sunflower spread and jam) was provided after 5 h and water was permitted throughout the study. Thirteen 7.5 ml blood samples were collected at 1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0 and 8.0 h post-dose. Samples were stored on ice and protected from light and within 1 h were centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min at approximately 2000 g. Plasma was divided into aliquots and stored at −70°C until analysis.

Meal design

Each of the three meals was formulated to represent a meal from typical UK dietary patterns. Dietary pattern analysis of data from the NDNS of adults 2000 – 1 has previously identified four dietary clusters for women and six for men, each characterised by their consumption of each of 25 food groups relative to the study population[32]. Of these clusters, three showed similar patterns for both men and women and were chosen for the meal design. Fahey et al.(32) assigned a name to each of the dietary clusters to describe its defining characteristics. These names are repeated here in order to aid identification. The ‘convenience’ cluster is characterised by higher than average consumption of fast foods and refined cereals and lower than average consumption of fruit, vegetables and whole grain cereals. The cosmopolitan cluster is characterised by higher than average consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish and dairy foods and the animal-oriented cluster is characterised by higher than average consumption of red meat and saturated fat. The three test-meals were designed to reflect the dietary characteristics of each cluster and, on the basis of food composition data contained equal amounts of phylloquinone (40 μg), energy (3200 kJ), energy from protein (20%), fat (40%) and carbohydrate (40%) and fibre (10.5 g). The meals were chicken pie with beans and chips (convenience), fish pie (cosmopolitan) and beef lasagne (animal-oriented). Dietary composition was estimated using the MRC HNR in-house suite of programs based on McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods, 4th edition[33], its supplements[34, 35] and the 6th edition[36]. Phylloquinone values were derived from the 6th edition[36], published values[18] and unpublished results (C Bolton-Smith and M Shearer). Meal composition is shown is Table 1. Each meal type was prepared in a single batch, cooked and frozen until required.

Table 1.

Weight and nutritional information for the convenience (a), cosmopolitan (b) and animal-oriented (c) test meals

| a Convenience meal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Energy | Protein | Fat | CHO | Fibre | Phylloquinone | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Ingredient | g | kJ | g | μg | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Chicken, light meat, raw | 95 | 427 | 22.8 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Baked beans | 70 | 249 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 10.7 | 4.8 | 1.9 |

| Milk, whole | 65 | 179 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Oven chips, frozen, baked | 60 | 414 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 18.0 | 1.7 | 2.8 |

| Bread, white | 40 | 402 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 19.7 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Flour, self-raising | 35 | 491 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 26.5 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| Margarine (soya based) | 25 | 677 | Tr | 18.3 | 0.1 | Tr | 19.5 |

| Onions | 20 | 19 | 0.2 | Tr | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Peas, frozen | 18 | 52 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.2 |

| Rapeseed oil | 9 | 333 | Tr | 9.0 | Tr | 0.0 | 10.1 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | 437 | 3243 | 38.1 | 35.1 | 80.8 | 11.0 | 40.5 |

| b Cosmopolitan meal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Energy | Protein | Fat | CHO | Fibre | Phylloquinone | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Ingredient | g | kJ | g | μg | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Potatoes, boiled | 260 | 796 | 4.7 | 0.3 | 44.2 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| Green beans, boiled | 84 | 78 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 32.7 |

| Bread, wholemeal | 65 | 601 | 6.1 | 1.7 | 27.1 | 4.8 | 1.7 |

| Milk, semi-skimmed | 50 | 99 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Haddock, smoked, raw | 50 | 173 | 9.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Tr |

| Salmon, raw | 45 | 337 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Cream, double | 25 | 462 | 0.4 | 12.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Cheese, cheddar | 20 | 342 | 5.1 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Fat (70%) spread | 5 | 130 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Butter | 4 | 121 | Tr | 3.3 | Tr | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Flour, plain | 4 | 58 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | Tr |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | 612 | 3197 | 38.6 | 34.4 | 79.9 | 10.9 | 40.5 |

| c Animal-oriented | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Energy | Protein | Fat | CHO | Fibre | Phylloquinone | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Ingredient | g | kJ | g | μg | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Tomatoes, canned | 160 | 110 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 9.6 |

| White bread | 95 | 955 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 46.9 | 3.5 | 0.4 |

| Beef, lean, raw | 95 | 490 | 19.2 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Milk, whole | 70 | 192 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Lasagna, boiled | 70 | 298 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 15.4 | 1.0 | Tr |

| Peas, frozen | 60 | 168 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 17.4 |

| Onions | 20 | 19 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Olive oil | 18 | 666 | 0.0 | 18.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.4 |

| Tomato puree | 10 | 29 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Fat (70%) spread | 5 | 130 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Butter | 4 | 121 | Tr | 3.3 | Tr | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Flour, plain | 4 | 58 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | Tr |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | 611 | 3236 | 37.6 | 35.0 | 81.4 | 10.4 | 40.4 |

CHO, carbohydrate

Analysis of phylloquinone in meals

The extraction of phylloquinone from the meals was based on the method described by Booth et al.[37]. Quantitation was performed by the standard addition method. Chemicals were purchased from VWR (VWR International Ltd, Poole, UK). One meal from each batch was defrosted and heated in the same way as for the subjects’ meals, then blended with an equal amount of warm purified water. A 30 g portion was homogenised using an IKA Ultra Turrax T25 basic homogeniser (Esslab, Essex, UK) and 2 g of the homogenised meal was transferred to a pestle and mortar and ground with 18 g of anhydrous sodium sulphate. One gram of the mixture was weighed into a 50 ml polypropylene centrifuge tube (Sarstedt Ltd, Leicester, UK) and 30 ml of 2-propanol: hexane (3:2 v/v) and 10 ml of purified water were added. At this stage, 3 ng of phylloquinone (Supelco, Poole, Dorset, UK) in 100 μl of hexane was added to half the tubes and to the remaining tubes was added 100 μl of hexane only. The tubes were vortexed for 3 min and then sonicated for 3 min with a Microsonix XL2000 model with 1/8 inch tapered microtip (Microsonix, USA). The tubes were further vortexed for 3 min and then centrifuged at 2000 g for 5 min. From the top layer, 9 ml of hexane was removed and transferred to a disposable culture tube (16 × 100 mm, Corning Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, UK) and evaporated under N2 at 45°C. The contents of the tube were reconstituted in 300 μl of hexane and further purified by solid phase extraction using 500 mg silica columns (Sep-Pak-RC™ 500 mg silica, Waters Hertfordshire, UK). The columns were conditioned with 4 ml diethyl ether: hexane (3.5:96.5 v/v) and then 4 ml of hexane. The sample was added and washed with 6 ml of hexane before elution with 7 ml of diethyl ether: hexane (3.5:96.5 v/v). The use of a C18 SPE purification step was also investigated but significant losses occurred during the washing steps and we found silica SPE alone provided sufficient purification. The sample eluent was collected into disposable glass tubes (13 × 100 mm, Fisher brand) and evaporated to dryness in a vacuum evaporator (Savant, NY, USA). The samples were reconstituted in 200 μl of dichloromethane and 800 μl of methanol and analysed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Extraction and analysis was performed in duplicate.

Quantitative analysis

Meal and total plasma phylloquinone were measured by HPLC with fluorescence detection after post-column reduction[38]. Long-term reproducibility of quality control plasma samples was assessed by their analysis in parallel with the unknowns to ensure the quality assurance in routine analysis. The lower limit of detection of phylloquinone by the described HPLC method is 0.04 nmol/l[38]. The interassay CVs of lyphilized human plasma standards (Immunodiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany) were 4.3% (mean 0.48 nmol/l, n=8) and 1.7% (mean 1.50 nmol/l, n=8). The laboratory also participates in the vitamin K external quality assurance scheme (KEQAS) run by the Human Nutristasis Unit at St Thomas’ Hospital.

Isotope ratio analysis

Isotope ratio measurements of phylloquinone in plasma were performed by GC/MS after extraction and derivatisation as described previously[30]. Briefly, sample extraction and clean-up was achieved by enzyme hydrolysis with lipase and cholesterol esterase, deproteination with ethanol, extraction with hexane, and solid phase extraction. Isotopic composition was determined in the pentafluoropropionyl derivative of phylloquinone. Analysis was performed on an Agilent GC/MS 5973N inert system (Agilent Technologies, Stockport, UK) comprising a 6890 GC with autosampler and equipped with on-column injection. The chromatography used a DB5-MS fused-silica capillary column (15 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). Ions 598.4 m/z to 602.4 m/z (M to M+4) were monitored in selected ion monitoring (SIM) and high-resolution mode. Isotope ratios and thus tracer concentrations were calculated using the M+1/M (599.4/598.4 m/z) ratio. The limit of quantitation of the GC/MS method is 0.3 nmol/l of total phylloquinone (labelled + unlabelled (endogenous and from the meal) and inter-assay precision is around 3%[30]. Isotopomer ratios were calculated using the fitting methods of Bluck and Coward[39] from the raw data generated by the GC/MS.

Calculations

Area under the curve (AUC) was used to assess absorption of the labelled phylloquinone tracer and was calculated using the trapezoid rule. Tracer AUC data assessed the effect of the meal on bioavailability of labelled phylloquinone from the capsule (‘meal effect’). AUC values were checked for normal distribution by observing a quintile-quintile plot. AUC for tracer measurements were compared using linear regression with fixed effects for meal, subject and period.

Tracer concentration was assessed calculated as:

Where RM+1 is the ratio of M+1 to M and at baseline (0) and subsequent time points (t). C(t) is the concentration of total (i.e. labelled + unlabelled) phylloquinone, assessed by HPLC.

For comparisons of the bioavailability of phylloquinone from the meals a different approach was taken. In each instance, if the absorption profile with time of phylloquinone from the meal were the same as that of the tracer then the relationship between them would be linear and with a 1:1 ratio after normalisation for the dose given by adjusting concentrations for the amount of phylloquinone provided as tracer or in the meal. By measuring the slope of regressions between normalised concentration of tracer and tracee from the meal, it was possible to measure the relative absorption of the phylloquinone from each meal compared to the tracer. This ‘matrix effect’ describes the extraction efficiency of phylloquinone from the meal. Data manipulation was performed in Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) and statistics were performed using STATA 9.1 (Stata Corp., Texas, USA).

Results

Mean (± SD) baseline plasma phylloquinone concentration was 0.35 ± 0.30 nmol/l. Mean baseline intra-individual coefficient of variation (CV) was 48%. The maximum total plasma phylloquinone increment in any subject was 2.5 nmol/l.

Phylloquinone in test meals measured by HPLC was 19.9 μg in the convenience meal, 26.3 μg in the cosmopolitan meal and 33.0 μg in the animal-oriented meal. The CV of results for duplicate extraction and analyses was less than 4%. For subsequent calculations the measured meal phylloquinone content was used rather than that calculated from food tables.

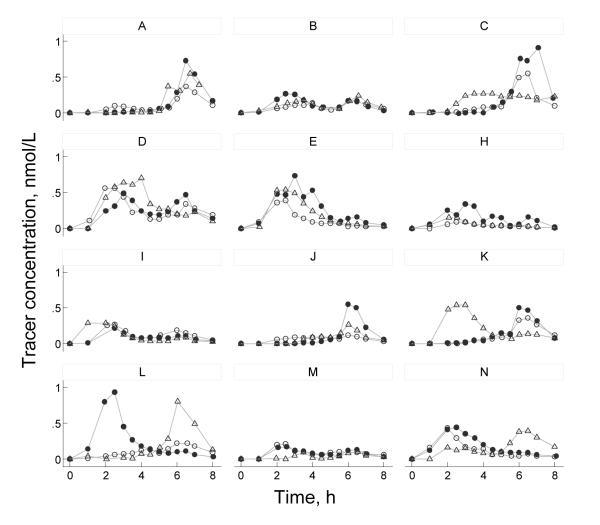

The means of tracer AUC measurements were 0.88 ± 0.43, 1.30 ± 0.48 and 1.13 ± 0.60 nmol/l.h for the convenience, cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals, respectively. Individual values are shown in Table 2. Significantly more phylloquinone tracer was absorbed when consumed with the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals than the convenience meal (P=0.001 and P=0.035, respectively). We did not detect any significant difference between the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals (P=0.120). There were no significant differences in AUC between genders, calculated using Students t-test (convenience P=0.83, cosmopolitan P=0.88, animal-oriented P=0.81). Calculation of AUC between 0 – 5 h and 5 – 8 h tested the possible influence of the 5 h snack on appearance of tracer phylloquinone in plasma. However, differences between meals in tracer absorption were similar before and after the snack. Profiles of plasma tracer against time are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Tracer AUC values for each individual and each meal

| Tracer AUC, nmol/L | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Subject | Convenience | Cosmopolitan | Animal- oriented |

| A | 0.81 | 1.11 | 0.85 |

| B | 0.64 | 0.94 | 0.84 |

| C | 1.04 | 1.71 | 1.31 |

| D | 2.04 | 1.87 | 2.44 |

| E | 0.94 | 2.03 | 1.51 |

| H | 0.30 | 1.11 | 0.45 |

| I | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.96 |

| J | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.57 |

| K | 0.82 | 1.02 | 1.59 |

| L | 0.78 | 1.99 | 1.49 |

| M | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.27 |

| N | 1.03 | 1.40 | 1.23 |

Figure 1.

Plasma phylloquinone tracer concentration v. time profiles for each subject, after oral administration of 20 μg 13C-labelled phylloquinone consumed together with the convenience meal (○), cosmopolitan meal (●), or animal-oriented meal (Δ).

Means (± SD) of the slopes of the relationship between tracer and meal tracee after adjustment for dose were 1.88 ± 0.81, 0.59 ± 0.32 and 0.43 ± 0.40 for convenience, cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals, respectively. Final relative bioavailability values (Table 3) between meals were calculated by multiplying values for the matrix and meal effects and are expressed relative to the convenience meal.

Table 3.

Summary of meal and matrix effects and combined relative bioavailability values for the three test meals

| Meal | Meal effect |

Meal effect (normalised) |

Matrix effect |

Matrix effect (normalised) |

Total effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.88 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cosmopolitan | 1.30 | 1.48 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Animal-oriented | 1.13 | 1.28 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.29 |

Meal effect refers to the effect of meal on absorption of tracer vitamin K1 calculated from AUC measurements of plasma tracer concentration. Matrix effect refers to the bioavailability of vitamin K1 from within the food matrix, relative to the tracer. The total effect is calculated as the product of the meal and matrix effects. Values are normalised to the convenience meal.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to develop and apply a stable isotope based method to measure phylloquinone bioavailability. We proposed a method using 13C-labelled tracer as a standard, taken at the same time as a test meal. Changes in plasma phylloquinone isotopic enrichment could then be used to calculate relative bioavailability of phylloquinone from the meals. However, dominance of the meal effect resulted in significant differences in tracer absorption between the meals. As a consequence, it was not possible to use the tracer as a global standard by which to compare phylloquinone absorption. An alternative approach was adopted where relative bioavailability of phylloquinone from the meals was assessed on the basis of the relationship between tracer and tracee absorption profile with time. Thus two, separate but interacting, determinants to bioavailability can be considered. Firstly, meal composition affects the bioavailability of free phylloquinone. This meal effect is the result of the meal modifying conditions within the gut and affecting digestion and/or absorption, and the potential enhancers or inhibitors of absorption. The second determinant, matrix effects or bioaccessibility, relate to the extraction of phylloquinone from the meal constituents. The appearance in plasma of 13C-labelled phylloquinone was used to determine meal effects, whereas the relationship between tracer and tracee phylloquinone was used to determine matrix effects. A final relative bioavailability value for each of the meals was determined as the product of the matrix and meal effects.

Absorption of phylloquinone from the capsule was significantly lower when taken with the convenience meal compared to the other meals. Such variation in absorption between meals has also been observed for stable isotope labelled vitamin E[26]. Various meal factors such as viscosity, particle size, meal volume, macronutrient content and energy density determine gastric emptying and intestinal transit[40], and these may affect phylloquinone bioavailability. To minimise differences in gastric emptying between the meals, all were balanced for fibre content, energy, and percent energy from fat, protein and carbohydrate. However, the convenience meal had a 50% greater energy density that may have influenced phylloquinone absorption. Borel et al.[41] investigated the effect of emulsified fat globule size on the absorption of vitamins A and E and concluded that the size of the particles does not affect absorption. Fat is required to stimulate bile secretion which is necessary for the absorption of phylloquinone[42]. Butter increased phylloquinone absorption from spinach threefold[19] but another study reported no difference in phylloquinone absorption between lettuce consumed with either 30 or 45 percent energy from fat[20]. Meals in the present study contained similar amounts of fat thus total fat is unlikely to explain the differences in absorption between meals. The fatty acid composition of a meal may affect absorption and plasma response by changing the physical characteristics of mixed micelles and/or influencing post-prandial lipid metabolism. Chylomicrons are the major carrier of post-prandial phylloquinone[43] and chylomicron remnants transport phylloquinone to both liver and also bone[44]. The size of mixed micelles may be important since longer chain fatty acids reduced phylloquinone absorption[45]. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) decreased phylloquinone absorption in in vitro[45] and rat[46] experiments, possibly through a greater affinity of the mixed micelle for phylloquinone decreasing transfer across the enterocyte. More recent studies in humans have shown that a polyunsaturated fatty acid-rich corn oil diet resulted in lower plasma phylloquinone compared to a diet enriched with olive/sunflower oil[47]. In the present study, the convenience meal contained more than two-fold greater PUFA (37% of total fat) than both the cosmopolitan (19%) and animal-oriented meals (14%). Inhibition of phylloquinone uptake or altered post-prandial metabolism by the high PUFA convenience meal could explain the lower absorption of phylloquinone from the capsule. Evidence suggests that vitamin E may affect phylloquinone status in rats[48, 49], however, other studies have shown effects are limited to tissue status, not plasma status, both in animal[50] and in human studies[51] thus it is likely that any effect is related to metabolism rather than absorption[47] [52]. In the current study, the vitamin E content of each meal, calculated using food composition tables, was 11.0 mg, 5.3 mg and 5.8 mg for the convenience, cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals, respectively.

Observation of the tracer profiles in Figure 1 reveals that in the majority of cases, an individual’s plasma tracer concentration profile shows a similar pattern for each test meal, and suggests that the differences in tracer profiles reflect genetic or physiological differences between individuals, e.g. transfer of phylloquinone across the enterocyte or chylomicron metabolism (apolipoprotein E genotype). High intra-individual consistency in absorption profiles of carotenoids has also been observed[53]. Although in general tracer profiles within individuals were similar for the different meals, subjects K, L and N showed substantial intra-individual differences in tracer absorption profile between the meals that may have confounded the results. As far as practicable external influences on digestion and absorption were controlled (such as previous meals, fasting and seating position) it is possible that these may have affected the absorption profile. In addition, particularly where absorption was apparently delayed, tracer concentration remained elevated beyond the 8 h duration of the experiment thus similar future studies might consider increasing the sampling period. These observations demonstrate that consideration should be given to potential variability of the absorption profile in bioavailability studies, particularly where absorption is assessed on the basis of a measurement at a single time point [54], and further supports the importance of crossover studies. Although generally there was some consistency in the extent of tracer absorption between the different meals for the same individual (assessed by rank) (Table 2), the potential variability in absorption of phylloquinone from the same meal eaten on different occasions for a given individual is unknown and may have influenced the data. A single study has reported the intra-individual variation of phylloquinone absorption, albeit of a very large dose of a pharmaceutical preparation of phylloquinone (2.2 μmol Konakion). CVs of the AUC measurements for three individuals each measured on three occasions were 18, 7 and 9%[19].

In a number of individuals, tracer phylloquinone peaked between 5 and 8 h, or a second smaller peak was observed, apparently in response to the 5 h snack. Although there were no differences in AUC before and after the snack, the snack may influence the plasma tracer profile. In some individuals, the physiological response to the snack may be the release of partially absorbed phylloquinone into the circulation. Dueker et al.[55] reported a similar observation with a second plasma peak of labelled β-carotene. A comparable phenomenon has also been reported with fatty acids, where fatty acids consumed during an initial meal appear in the circulation after a second meal a number of hours later[56, 57]. An alternative explanation for the second peak is hepatic secretion of VLDL containing phylloquinone[27, 43, 58].

In contrast to tracer absorption, and on the basis of the matrix effect alone, absorption of phylloquinone from the convenience meal was more than threefold that from the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals. Whilst the magnitude of this difference was reduced with the inclusion of the meal effect (tracer data), total relative bioavailability remained greater from the convenience meal. Greater absorption of phylloquinone from the convenience meal may be expected given the sources of phylloquinone. In the convenience meal, it can be estimated that more than 80% of the phylloquinone was in the oil phase whereas in the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals only 10% and 20% of phylloquinone was in oil, respectively. Conversely, the majority of phylloquinone in the cosmopolitan and animal-oriented meals was sited within a vegetable matrix where it is tightly bound to the thylakoid membranes and may be less bioavailable because cell walls and membranes must be digested before absorption. Although it is generally assumed that fat-soluble vitamin absorption is greater from fat than from vegetables, there have been few direct comparisons[59]. Previous studies to compare the bioavailability of phylloquinone from oil and vegetables have shown conflicting results. In one study, absorption, calculated by 24 h AUC, was reported to be significantly greater from oil than from broccoli[23] but an earlier study, that measured absorption of phylloquinone from multiple meals over 5 d, found no difference in absorption between these two sources[22]. A number of caveats are applicable to our interpretation of the matrix effect data. Firstly, due to low phylloquinone content of the meals and low absorption, the plasma phylloquinone content attributable to phylloquinone from the meal was towards the lower end of analytical limits. Plasma phylloquinone concentration from the meal across the time course of the experiment was between 0.2 and 1 nmol/l. Secondly, and as discussed above in relation to the tracer data, there was variability in the pattern of phylloquinone appearance in plasma and in responses with the different meals, both of which may have influenced our interpretation of the matrix effect. Thirdly, although the mixed meal provides the opportunity to assess the combined impact of foods, interpretation of these effects is complicated by the many interacting factors.

Previous phylloquinone absorption studies have primarily tested single foods, either individually or in combination with untypical food combinations. The meal-based method described here was an attempt to use a less subjective approach to the design of test meals with the aim that they represent more accurately meals in a free-living situation in which food components may interact to negate effects observed in experiments with individual foods. The three meals in this study were designed using the characteristics of dietary clusters identified in a national nutrition survey. The use of dietary analysis in this way provides a basis for the design of test meals in bioavailability experiments that can be used to probe relationships between dietary intake and plasma response and/or status. The meals were designed to contain equal amounts of phylloquinone, with the major difference between the meals, the sources of phylloquinone. However, direct analysis of meals revealed variation in the measured value compared to that calculated from nutrient tables. The observed discrepancy however is not unusual; the phylloquinone content of foods is known to be highly variable and affected by heating[60]. Furthermore, a comparison of the phylloquinone content of ten meals calculated by two nutrient databases compared to direct analysis showed variation of up to 89%[61].

In summary, we have investigated a meal-based approach to measurements of absorption that is more relevant to the consumption of foods in a free-living population. The apparent dominance of the meal effect showed that different meals affect absorption of phylloquinone, although the mechanism is unknown. Notwithstanding the potential limitations, the data also suggest that phylloquinone may be more bioavailable from oils and fats than from vegetable sources.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the UK Food Standards Agency for funding this work (project number N05050). We would like to thank Louise McKenna for assistance in sample extraction and analysis, and the volunteers for participating in the study. We also thank Dr Adrian Mander and Mark Chatfield for statistical advice.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Department of Health . Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom. Report on Health and Social Subjects No. 41. HMSO; London: 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Referenzwerte D-A-C. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung, Österreichische Gesellschaft für Ernährung, Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ernährungsforschung, Schweizerische Vereinigung für Ernährung: Referenzwerte für die Nährstoffzufuhr. Umschau/Braus Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thane CW, Bolton-Smith C, Coward WA. Comparative dietary intake and sources of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) among British adults in 1986-7 and 2000-1. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:1105–1115. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkley NC, Krueger DC, Engelke JA, Foley AL, Suttie JW. Vitamin K supplementation reduces serum concentrations of under-γ-carboxylated osteocalcin in healthy young and elderly adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1523–1528. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bügel S, Sørenson AD, Hels O, Kristensen M, Vermeer C, Jakobsen J, Flynn A, Mølgaard C, Cashman KD. Effect of phylloquinone supplementation on biochemical markers of vitamin K status and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:373–380. doi: 10.1017/S000711450715460X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cranenburg ECM, Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Vitamin K: The coagulation vitamin that became omnipotent. Thrombo Haemost. 2007;98:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Booth SL, Broe KE, Gagnon DR, et al. Vitamin K intake and bone mineral density in women and men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:512–516. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feskanich D, Weber P, Willett WC, Rockett H, Booth SL, Colditz GA. Vitamin K intake and hip fractures in women: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:74–79. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth SL, Tucker KL, Chen H, et al. Dietary vitamin K intakes are associated with hip fracture but not with bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1201–1208. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binkley N, Harke J, Krueger D, Engelke J, Vallarta-Ast N, Gemar D, Checovich M, Chappell R, Suttie J. Vitamin K treatment reduces undercarboxylated osteocalcin but does not alter bone turnover, density or geometry in healthy postmenopausal North American women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081254. 10.1359/jbmr.081254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth SL, Dallal G, Shea MK, Gundberg C, Peterson JW, Dawson-Hughes B. Effect of Vitamin K Supplementation on Bone Loss in Elderly Men and Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1217–1223. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung AM, Tile L, Lee Y, et al. Vitamin K supplementation in postmenopausal women with osteopenia (ECKO Trial): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:e196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thane CW, Wang LY, Coward WA. Plasma phylloquinone (vitamin K1) concentration and its relationship to intake in British adults aged 19-64 years. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:1116–1124. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan T, Wynne H, Wood P, Torrance A, Hankey C, Avery P, Kesteven P, Kamali F. Dietary vitamin K influences intra-individual variability in anticoagulant response to warfarin. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:348–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couris R, Tataronis G, McCloskey W, Oertel L, Dallal G, Dwyer J, Blumberg JB. Dietary vitamin K variability affects International Normalized Ratio (INR) coagulation indices. Int J Vit Nutr Res. 2006;76:65–74. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.76.2.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Custódio das Dôres SM, Booth SL, Aújo Martini L, de Carvalho Gouvêa VH, Padovani CR, de Abreu Maffei FH, Campana ÁO, Rupp de Paiva SA. Relationship between diet and anticoagulant response to warfarin: a factor analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2007;46:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00394-007-0645-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duggan P, Cashman KD, Flynn A, Bolton-Smith C, Kiely M. Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) intakes and food sources in 18-64-year-old Irish adults. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:151–158. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolton-Smith C, Price RJ, Fenton ST, Harrington DJ, Shearer MJ. Compilation of a provisional UK database for the phylloquinone (vitamin K1) content of foods. Br J Nutr. 2000;83:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gijsbers BL, Jie KS, Vermeer C. Effect of food composition on vitamin K absorption in human volunteers. Br J Nutr. 1996;76:223–229. doi: 10.1079/bjn19960027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garber AK, Binkley NC, Krueger DC, Suttie JW. Comparison of phylloquinone bioavailability from food sources or a supplement in human subjects. J Nutr. 1999;129:1201–1203. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Determination of phylloquinone and menaquinones in food. Effect of food matrix on circulating vitamin K concentrations. Haemostasis. 2000;30:298–307. doi: 10.1159/000054147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Booth SL, O’Brien-Morse ME, Dallal GE, Davidson KW, Gundberg CM. Response of vitamin K status to different intakes and sources of phylloquinone-rich foods: comparison of younger and older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:368–377. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth SL, Lichtenstein AH, Dallal GE. Phylloquinone absorption from phylloquinone-fortified oil is greater than from a vegetable in younger and older men and women. J Nutr. 2002;132:2609–2612. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeum K-J, Russell RM. Carotenoid bioavailability and bioconversion. Ann Rev Nutr. 2002;22:483–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates CJ, Jones KS, Bluck LJ. Stable isotope-labelled vitamin C as a probe for vitamin C absorption by human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:699–705. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeanes YM, Hall WL, Ellard S, Lee E, Lodge JK. The absorption of vitamin E is influenced by the amount of fat in a meal and the food matrix. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:575–579. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erkkilä AT, Lichtenstein AH, Dolnikowski GG, Grusak MA, Jalbert SM, Aquino KA, Peterson JW, Booth SL. Plasma transport of vitamin K in men using deuterium-labeled collard greens. Metabolism. 2004;53:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolnikowski GG, Sun Z, Grusak MA, Peterson JW, Booth SL. HPLC and GC/MS determination of deuterated vitamin K (phylloquinone) in human serum after ingestion of deuterium-labeled broccoli. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:168–174. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(01)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurilich AC, Britz SJ, Clevidence BA, Novotny JA. Isotopic labeling and LC-APCI-MS quantification for investigating absorption of carotenoids and phylloquinone from kale (Brassica oleracea) J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4877–4883. doi: 10.1021/jf021245t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones KS, Bluck LJC, Coward WA. Analysis of isotope ratios in vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) from human plasma by gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:1894–1898. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones KS, Bluck LJC, Wang LY, Coward WA. A dual stable isotope approach for the simultaneous measurement of vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) kinetics and absorption. Euro J Clin Nutr. 2007;62:1273–1281. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahey MT, Thane CW, Bramwell GD, Coward WA. Conditional Gaussian mixture modelling for dietary pattern analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2007;170:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul AA, Southgate DAT. McCance and Widdownson’s The Composition of Foods. 4th edition HMSO; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland B, Unwin ID, Buss DH. Cereals and Cereal Products: Third Supplement to McCance & Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. 4th edition Royal Society of Chemistry Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; Nottingham: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland B, Unwin ID, Buss DH. Milk Products and Eggs: Fourth Supplement to McCance & Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. 4th edition Royal Society of Chemistry Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; Cambridge: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Food Standards Agency . McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. 6th summary ed Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth SL, Davidson KW, Sadowski JA. Evaluation of an HPLC method for the determination of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in various food matrices. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang LY, Bates CJ, Yan L, Harrington DJ, Shearer MJ, Prentice A. Determination of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in plasma and serum by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;347:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bluck LJC, Coward WA. Peak measurement in gas chromatographic mass spectrometric isotope studies. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:1212–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Low AG. Nutritional regulation of gastric secretion, digestion and emptying. Nutr Res Rev. 1990;3:229–252. doi: 10.1079/NRR19900014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borel P, Pasquier B, Armand M, et al. Processing of vitamin A and E in the human gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G95–G103. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.1.G95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearer MJ, McBurney A, Barkhan P. Studies on the absorption and metabolism of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in man. Vitam Horm. 1974;32:513–542. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamon-Fava S, Sadowski JA, Davidson KW, O’Brien ME, McNamara JR, Schaefer EJ. Plasma lipoproteins as carriers of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:1226–1231. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niemeier A, Kassem M, Toedter K, Wendt D, Ruether W, Beisiegel U, Heeren J. Expression of LRP1 by human osteoblasts: a mechanism for the delivery of lipoproteins and vitamin K1 to bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:283–293. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollander D, Rim E. Factors affecting the absorption of vitamin K-1 in vitro. Gut. 1976;17:450–455. doi: 10.1136/gut.17.6.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollander D, Rim E, Muralidhara KS. Vitamin K1 intestinal absorption in vivo: influence of luminal contents on transport. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1977;232:E69–E74. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1977.232.1.E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schurgers LJ, Shearer MJ, Soute BA, Elmadfa I, Harvey J, Wagner KH, Tomasch R, Vermeer C. Novel effects of diets enriched with corn oil or with an olive oil/sunflower oil mixture on vitamin K metabolism and vitamin K-dependent proteins in young men. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:878–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander GD, Suttie JW. The effect of vitamin E on vitamin K activity. FASEB Journal. 1999;40:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell GV, Cook KK, Jenkins MY, Grundel E. Supplementation of rats with a lutein mixture preserved with vitamin E reduces tissue phylloquinone and menaquinone-4. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2001;71:30–35. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.71.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tovar A, Ameho CK, Blumberg JB, Peterson JW, Smith D, Booth SL. Extrahepatic tissue concentrations of vitamin K are lower in rats fed a high vitamin E diet. Nutr Metab. 2006;3 doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Booth SL, Golly I, Sacheck JM, Roubenoff R, Dallal GE, Hamada K, Blumberg JB. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on vitamin K status in adults with normal coagulation status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:143–148. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Traber MG. Vitamin E and K interactions - a 50-year-old problem. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:624–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faulks RM, Southon S. Challenges to understanding and measuring carotenoid bioavailability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schurgers LJ, Teunissen KJF, Hamulyak K, Knapen MHJ, Vik H, Vermeer C. Vitamin K-containing dietary supplements: comparison of synthetic vitamin K1 and natto-derived menaquinone-7. Blood. 2007;109:3279–3283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dueker SR, Lin Y, Buchholz BA, Schneider PD, Lamé MW, Segall HJ, Vogel JS, Clifford AJ. Long-term kinetic study of β-carotene, using accelerator mass spectrometry in an adult volunteer. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1790–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fielding B, Callow J, Owen R, Samra J, Matthews D, Frayn K. Postprandial lipemia: the origin of an early peak studied by specific dietary fatty acid intake during sequential meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:36–41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maillot F, Garrigue MA, Pinault M, et al. Changes in plasma triacylglycerol concentrations after sequential lunch and dinner in healthy subjects. Diabetes Metab. 2005;31:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Differential lipoprotein transport pathways of K-vitamins in healthy subjects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1570:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parker RS, Swanson JE, You CS, Edwards AJ, Huang T. Bioavailability of carotenoids in human subjects. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:155–162. doi: 10.1079/pns19990021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferland G, Sadowski JA. Vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) content of edible oils: effects of heating and light exposure. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:1869–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKeown NM, Rasmussen HM, Charnley JM, Wood RJ, Booth SL. Accuracy of phylloquinone (vitamin K-1) data in 2 nutrient databases as determined by direct laboratory analysis of diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]