Abstract

The cyclopentenone prostaglandin (cPG) 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) has been identified as a potent antiinflammatory agent that is able to inhibit the activation of macrophages and microglia. Additionally, 15d-PGJ2 is able to ameliorate the clinical manifestations of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS). Many biological effects of 15d-PGJ2 have been attributed to the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ). PGA2, like 15d-PGJ2, is a cPG. The aim of this study is to compare the relative effectiveness of these two cPGs in inhibiting the inflammatory response of mouse microglia and astrocytes, two cell types that upon activation may contribute to the pathology of EAE and MS. Purified primary mouse microglia and astrocytes were treated with either 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 and then stimulated with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or a combination of interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. The results show that 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 both potently inhibited the production of nitrite, as well as proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, from microglia and astrocytes. Generally, regulation of NO production was more sensitive to 15d-PGJ2, however, cytokine and chemokine production was more sensitive to PGA2 treatment. These results demonstrate for the first time that PGA2 is a potent antiinflammatory mediator.

Keywords: primary cell culture, cytokine, chemokine, mouse

Prostaglandins (PGs) are a family of biologically active molecules that have been implicated in numerous physiologic and pathologic processes (Straus and Glass, 2001). PGs are oxygenated metabolites of arachidonic acid and are divided into two main functional groups. The conventional PGs, including PGE, PGD, and PGF, elicit a biological response after binding to G protein-coupled cell surface receptors. In contrast, the cyclopentenone PGs (cPG), including PGA1, PGA2, and PGJ2, have no cell surface receptor but instead are actively transported into the cell where they are able to interact with signaling molecules and transcription factors. The bioactivity of cPGs has been attributed in part to the chemically reactive α, β-unsaturated carbonyl group located in the cyclopentenone ring that makes these PGs susceptible to undergoing Michael addition reactions with cysteine residues located in cellular proteins (Bui and Straus, 1998; Straus et al., 2000; Straus and Glass, 2001). Additionally, the γ isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR-γ) has been found to be a specific nuclear receptor for the cPG 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) (Forman et al., 1995; Kliewer et al., 1995). PPAR-γ heterodimerizes with the 9-cis retinoic acid receptor, translocates to the nucleus, and recognizes the PPAR response element (PPRE) in the promoters of target genes, suggesting an alternative route of action for the cPG 15d-PGJ2 (Kielian and Drew, 2003).

Cyclopentenone PGs have a variety of biological actions, including induction of the cellular stress response, inhibition of cell-cycle progression, and suppression of viral replication, cell differentiation, and development (Negishi and Katoh, 2002). Recently, the role of cPGs as antiinflammatory mediators has been identified. The cPG 15d-PGJ2 has been shown to be effective in ameliorating a variety of inflammatory conditions including arthritis (Kawahito et al., 2000) and inflammatory bowel disease (Su et al., 1999). In addition, elevated serum levels of 15d-PGJ2 correlate with the resolution of inflammation in a carrageenin-induced pleurisy model (Gilroy et al., 1999). More recently, we and others have demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 is effective in inhibiting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a rodent model of multiple sclerosis (Diab et al., 2002, 2004; Feinstein et al., 2002; Natarajan and Bright, 2002).

The mechanisms underlying the ability of cPGs to induce antiinflammatory effects have been studied only recently. The cPG 15d-PGJ2 has been demonstrated to repress the expression of numerous proinflammatory genes in activated macrophages including those encoding inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, gelatinase B, thromboxane B2, and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 (Jiang et al., 1998; Ricote et al., 1998; Guyton et al., 2001). Activated glia are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases including MS. Importantly, 15d-PGJ2 inhibited the production of nitric oxide (NO) in activated microglia after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation (Petrova et al., 1999), and was able to inhibit expression of iNOS, TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and COX-2 in LPS-stimulated microglia (Bernardo et al., 2000, 2003; Koppal et al., 2000). In addition, we have shown that 15d-PGJ2 is effective in inhibiting production of potentially cytotoxic molecules, including NO, TNF-α, and IL-12, by microglial cells stimulated with interferon (IFN) -γ and TNF-α, molecules that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of EAE and MS (Drew and Chavis, 2001). The mechanisms by which cPGs alter the expression of proinflammatory genes have not been elucidated completely. Binding of the ligand 15d-PGJ2 to PPAR-γ can directly modulate gene transcription through receptor binding to the PPRE present in PPAR-γ-responsive genes. Alternatively, 15d-PGJ2 may also alter gene expression independent of the PPRE, through a mechanism termed receptor-dependent transrepression. In addition, 15d-PGJ2 is believed to inhibit DNA binding of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), and AP-1, transcription factors that promote transcription of proinflammatory genes, through receptor-dependent transrepression. Furthermore, 15d-PGJ2 can inhibit NF-κB activation by suppressing IκB phosphorylation via PPAR-γ independent mechanisms (Straus et al., 2000; Park et al., 2003). The cyclopentenone ring of 15d-PGJ2 has been demonstrated to mediate some PPAR-γ-independent effects of this PG (Kielian and Drew, 2003).

The current study aims to examine the ability of the cPG PGA2 to suppress the activation of microglia and astrocytes. In addition, we directly compare the activity of PGA2 with that of15d-PGJ2. The results show that PGA2 is effective in inhibiting the production of NO and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from both activated microglia and astrocytes. To our knowledge, this is the first thorough demonstration that PGA2 may have an antiinflammatory role in the regulation of activated glial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The cPGs 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 PGJ2 and PGA2 were obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). LPS was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), whereas the cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Hyclone (Logan, UT).

Cell Culture

Pure mouse microglia and astrocyte cultures were obtained through a modification of the McCarthy and de Vellis (1980) protocol. Briefly, cerebral cortices from 1–2-day-old mouse pups were excised and cortices minced into small pieces. Cells were separated by trypsinization in the presence of DNase and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. After filtration through a 70-μm strainer, the cells were collected by centrifugation (153 × g for 5 min at 4°C). The cells were re-suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS, 1.4 mM glutamine, 0.5 ng/ml granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and oxaloacetate pyruvate insulin (OPI) media supplement (Sigma), plated into tissue culture flasks, and allowed to grow to confluence (about 10 days) at 37°C/5% CO2. Flasks were shaken overnight (200 rpm at 37°C) in a temperature-controlled shaker to loosen microglia and oligodendrocytes from the more adherent astrocytes. These less adherent cells were plated for 2 hr and then lightly shaken to separate oligodendrocytes from the more adherent microglia. Microglial cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C/5% CO2. Astrocyte medium contained all the substances described in the defined medium above except GM-CSF. After shaking to remove microglia and oligodendrocytes, astrocytes were recovered by trypsinization, seeded in 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C/5% CO2. These panning procedures were repeated to obtain primary microglia or astrocytes of greater than 95% purity as determined by immunohistochemistry. Microglial and astroglial cells were treated with either 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 for 1 hr, and then stimulated with LPS or IFN-γ/TNF-α for 24 hr. Finally, tissue culture supernatants were collected to analyze for NO levels and cytokine/chemokine secretion.

NO Production

The production of NO was monitored by measuring the amount of nitrite, one of the end products of NO oxidation, in the supernatant. This assay was accomplished using the Griess reaction, which is based on the diazotization of nitrite by sulfanilic acid. Plates were read on a Molecular Devices Spectromax 190 microplate reader using a test wavelength of 550 nm. Results are reported as the average molar amount of nitrite released into the supernatant. Each experimental condition was run in triplicate.

Cell Viability Assays

Cellular viability was determined by measuring the reduction of cellular 3-(4, 5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) as described previously (Chang et al., 1998). Briefly, MTT was added during the final 1hr of incubation. The medium was removed, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well, and the plate shaken for 30 min at room temperature. The plate was then read on a Spectromax 190 microplate reader using a test wavelength of 570 nm. Results are reported as the percent viability as compared to unstimulated microglia.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Cytokine (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and chemokine (monocyte chemoattractant protein [MCP]-1) levels in tissue culture media were determined by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described by the manufacturer (OptEIA mouse ELISA kit; BD Pharmingen). Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in the tissue culture media were determined by spectrophotometer using a test wavelength of 450 nm and calibrated from standards containing known concentrations of the cytokine.

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test at a 95% confidence level were used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

Effects of Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins on NO Production by Microglial Cells After LPS Stimulation

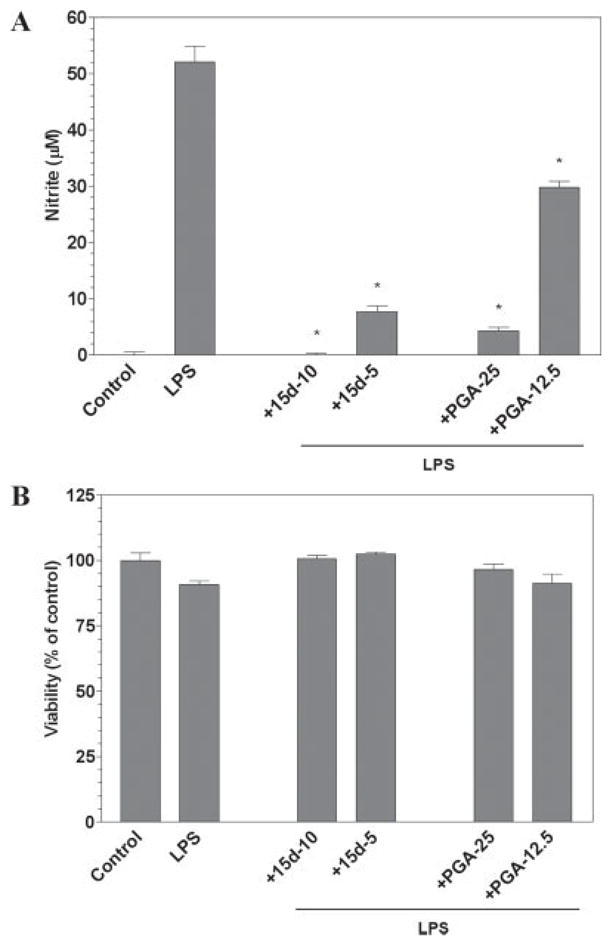

We have demonstrated previously that the prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 represses the production of NO by a mouse microglial cell line and primary rat microglia (Drew and Chavis, 2001). In the present studies, we investigated the ability of another cPG to influence the activity of activated microglia. In mouse primary microglial cells, LPS was able to induce the production of NO (Fig. 1A), and 15d-PGJ2 was able to repress NO production in a dose-dependent manner, without a change in cell viability relative to LPS alone (Fig. 1A,B). Similarly, PGA2 was able to inhibit the production of NO by mouse primary microglia in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), without significantly altering the level of cell viability (Fig. 1B). The effective dose of PGA2 was approximately three- to fivefold higher than that needed for 15d-PGJ2 to suppress NO production.

Fig. 1.

The cyclopentenone prostaglandins 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 inhibit LPS induction of NO by microglial cells. Primary microglia were plated at 40,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with the indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (in μM). LPS (0.5 μg/ml) was added as indicated and 24 hr later, the concentration of nitrite in the culture medium was determined (A). Cell viability was determined by MTT assay (B). Shown are the results of a representative experiment, and each experiment was conducted independently at least three times. Values represent the mean ± SEM for triplicate cultures. *P < 0.01 vs. LPS-treated cultures.

Effects of Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins on NO Production by Microglial Cells After Cytokine Stimulation

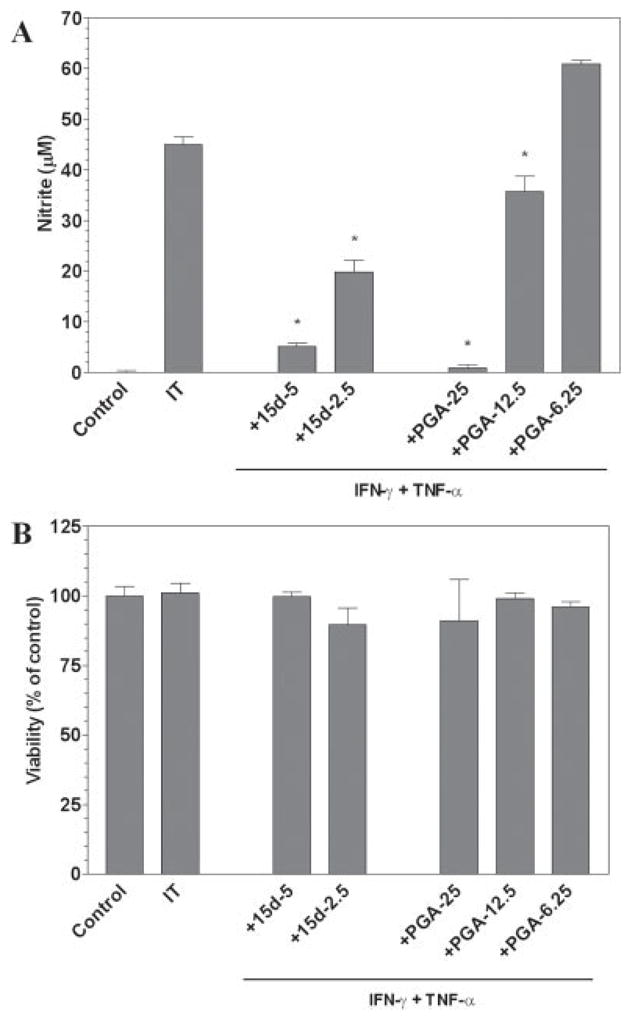

The proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ are capable of stimulating microglial cells and are considered to be important modulators in MS. We thus wanted to examine the ability of cPGs to alter microglial activity after cytokine-induced activation. Administration of IFN-γ and TNF-α (IT) resulted in the production of NO in mouse primary microglial cells (Fig. 2A). The cPG 15d-PGJ2 was able to repress the production of NO in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). There was no effect on cell viability with these treatments (Fig. 2B). Additionally, administration of PGA2 also resulted in the dose-dependent suppression of NO levels when compared to IT alone (Fig. 2A). There was no effect on cell viability when compared to IT stimulation alone after PGA2 treatment (Fig. 2B). The effective dose of PGA2 in suppressing NO levels was again three- to fivefold higher than the dose of 15d-PGJ2 required to suppress NO production.

Fig. 2.

The cyclopentenone prostaglandins 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 inhibit IFN-γ plus TNF-α induction of NO by microglial cells. Primary microglia were plated at 40,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day cells were pretreated for 1 hr with the indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (in μM). IFN-γ (250 U/ml) and TNF-α (500 U/ml) were added as indicated and 24 hr later, the concentration of nitrite in the culture medium was determined (A). Cell viability was determined by MTT assay (B). Shown are the results of a representative experiment, and each experiment was conducted independently at least three times. Values represent the mean ± SEM for triplicate cultures. *P < 0.01 vs. IT-treated cultures.

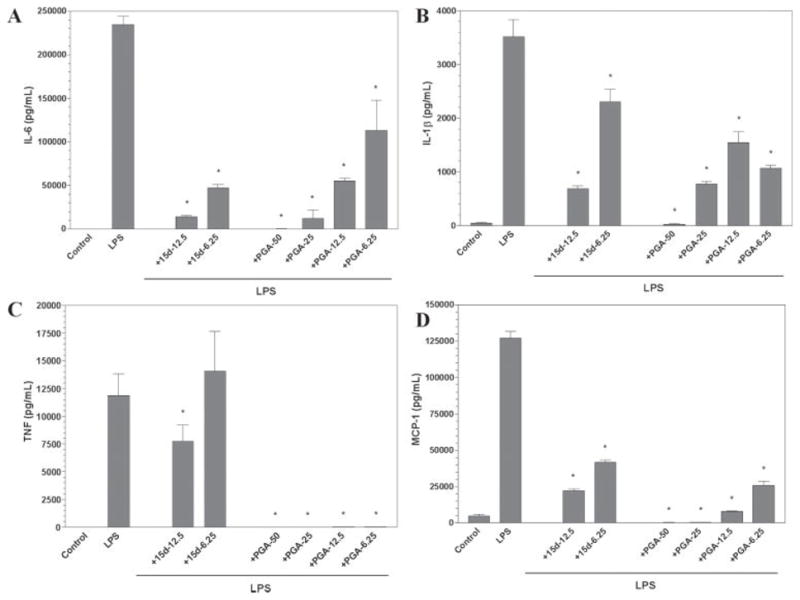

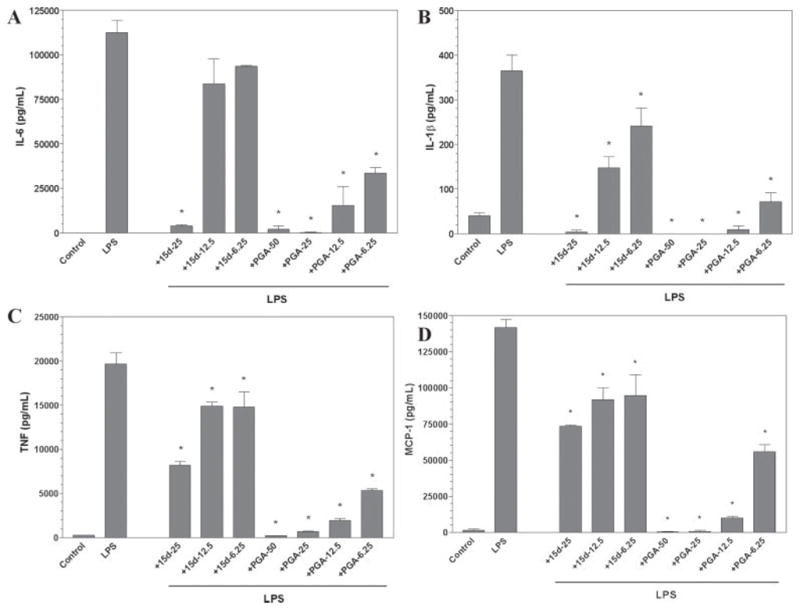

Effects of Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins on Cytokine and Chemokine Production by Microglial Cells

To test the ability of cyclopentenone prostaglandins to alter the production of proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines, we utilized ELISA to examine the release of soluble factors from primary mouse microglia after stimulation with LPS (Fig. 3). Stimulation of microglia with LPS was able to induce the secretion of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and the chemokine MCP-1 (Fig. 3). Pretreatment of microglial cells with either 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 was able to suppress the production of all cytokines examined. Additionally, both prostaglandins were effective in inhibiting the secretion of the chemokine MCP-1. In contrast to the dose parameters observed in the nitrite studies, PGA2 was generally two- to threefold more effective as an inhibitor of both cytokine and chemokine secretion relative to 15d-PGJ2.

Fig. 3.

The cyclopentenone prostaglandins 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 inhibit cytokine and chemokine production by microglial cells. Primary microglia were plated at 40,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day cells were pretreated for 1 hr with the indicated concentration of 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (in μM), then LPS (0.5 μg/ml) was added as indicated, and 24 hr later, IL-6 (A), IL-1β (B), TNF-α (C), and MCP-1 (D) levels were determined in culture media by ELISA. Shown are the results of a representative experiment, and each experiment was conducted independently at least three times. Values represent the mean ± SEM for triplicate cultures. *P < 0.01 vs. LPS-treated cultures.

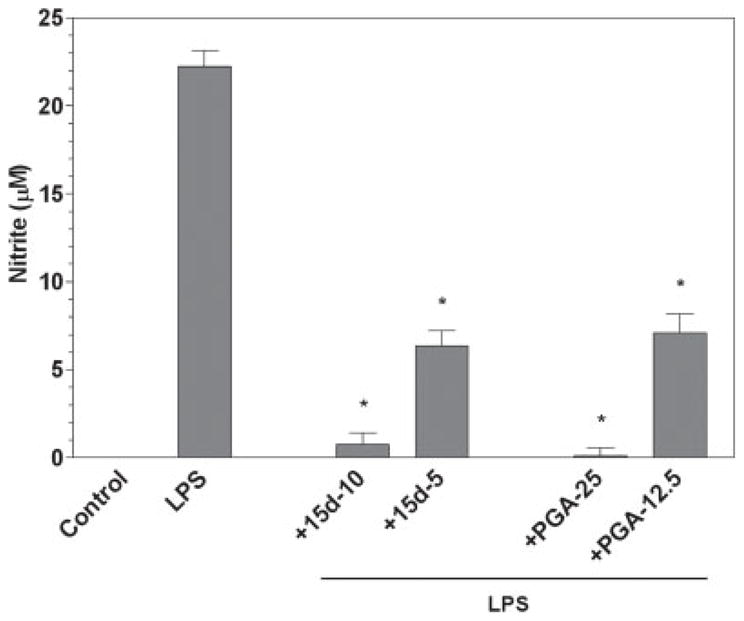

Effects of Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins on NO, Cytokine, and Chemokine Production by Astrocytes

Activated astrocytes, like activated microglia, have also been implicated in the course of MS as they are able to produce NO and many proinflammatory cytokine and chemokines that may contribute to disease progression. We examined the ability of cPGs to modulate the inflammatory activity of activated primary mouse astrocytes. Stimulation of astrocytes with LPS was able to induce NO production (Fig. 4). Treatment with 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 resulted in dose-dependent suppression of NO production. Similar to the effects in microglia,15d-PGJ2 was more effective than PGA2 in suppressing NO production by stimulated astrocytes. There was no decrease in cell viability detected after LPS stimulation or after treatment with 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

The cyclopentenone prostaglandins 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 inhibit LPS induction of NO by astrocytes. Primary astrocytes were plated at 50,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day cells were pretreated for 1 hr with the indicated concentration of 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (in μM), then LPS (2 μg/ml) was added as indicated, and 24 hr later, the concentration of nitrite in the culture medium was determined. Shown are the results of a representative experiment, and each experiment was conducted independently a minimum of three times. Values represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. *P < 0.01 vs. LPS-treated cultures.

Furthermore, LPS stimulated the production and release of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and the chemokine MCP-1 from primary mouse astrocytes as determined by ELISA analysis (Fig. 5). Similar to the effects on primary mouse microglia, both 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 potently suppressed the production of these cytokines and chemokine (Fig. 5) from LPS-stimulated astrocytes. Additionally, PGA2 was more effective than 15d-PGJ2 in inhibiting cytokine and chemokine release from activated astrocytes.

Fig. 5.

The cyclopentenone prostaglandins 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 inhibit cytokine and chemokine production by astrocytes. Primary astrocytes were plated at 50,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day cells were pretreated for 1 hr with the indicated concentration of 15d-PGJ2 or PGA2 (in μM). LPS (2 μg/ml) was added as indicated, and 24 hr later, IL-6 (A), IL-1β (B), TNF-α (C), and MCP-1 (D) levels were determined in culture media by ELISA. Shown are the results of a representative experiment, and each experiment was conducted independently at least three times. Values represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. *P < 0.01 vs. LPS-treated cultures.

DISCUSSION

MS is characterized by demyelination and neuronal injury that are a result of an immune response directed at antigens of the CNS (Lutton et al., 2004). Activated myelin-specific T cells are believed to play a role in the induction of this presumed autoimmune disease (Martin et al., 1992; Stinissen et al., 1998; Xiao and Link, 1999; Steinman, 2001; Yan et al., 2003). A major effector role for resident glial cells, including microglia and astroglia, however, has been identified in the pathology of MS (Benveniste, 1997; De Keyser et al., 2003). Inflammation leads to the activation of resident microglia and astrocytes and results in the production of reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory cytokines, and chemokines that can be directly or indirectly toxic to oligodendrocytes and neurons, perpetuate immune cell activation, and facilitate extravasation of immune cells into the CNS. Actions that result in the suppression of microglial and astroglial activation may thus provide potential avenues for the treatment of MS.

NO has a wide range of biological actions and has been implicated in numerous aspects of the inflammatory response (Willenborg et al., 1999). The role for NO in EAE and MS is somewhat controversial. Chronically activated glia are believed to produce high levels of NO, which is believed to contribute to the pathogenesis associated with these disorders; however, mice in which the iNOS gene is inactivated are more susceptible to EAE (Fenyk-Melody et al., 1998; Sahrbacher et al., 1998; van der Veen et al., 2003; Kahl et al., 2004). In the course of EAE or MS, NO may thus be protective or alternatively destructive.

The current study demonstrates that the cPGs 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 are effective in inhibiting NO production by mouse microglia after stimulation with either LPS or IFN-γ/TNF-α. The ability of 15d-PGJ2 to inhibit NO production has been described previously in mouse and rat macrophages (Ricote et al., 1998; Guyton et al., 2001; Alleva et al., 2002) and also in rat primary microglia (Bernardo et al., 2000; Drew and Chavis, 2001). Both PGA2 and 15d-PGJ2 had similar patterns of inhibition, but 15d-PGJ2 was more potent, illustrated by the lower concentration required to inhibit NO production. This difference may be explained in part by the alternate pathways of action that exist between these two cPGs. Both cPGs are actively transported into the cell and are able to elicit biological actions via the reactive carbonyl group in the cyclopentenone ring structure; however, 15d-PGJ2 is known to be a specific ligand for PPAR-γ, a nuclear receptor that is able to alter gene transcription after binding to specific response elements in the promoter of target genes. In addition, 15d-PGJ2 may also inhibit NO production by PPAR-γ independent mechanisms. For example, 15d-PGJ2 was demonstrated previously to inhibit the activity of NF-κB independently of PPAR-γ, but the potency of 15d-PGJ2 increased when these cells were induced to express PPAR-γ (Ricote et al., 1998). Additionally, higher concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 were required to inhibit iNOS expression in cells that lacked PPAR-γ when compared to cells that did express PPAR-γ (Petrova et al., 1999). Numerous studies have demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 is able to inhibit the expression of iNOS (Petrova et al., 1999; Bernardo et al., 2000; Koppal et al., 2000; Drew and Chavis, 2001; Chen et al., 2003); however, the ability of PGA2 to alter this enzyme has not been studied to date.

Activated microglial cells are also the source of numerous proinflammatory cytokines that may contribute to the pathology of several inflammatory disorders in the CNS, including MS (Brosnan et al., 1995; Cannella and Raine, 1995; Benveniste, 1997). In MS, the expression of numerous cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 are found at very high levels in the area of active lesions (Cannella and Raine, 1995; Samoilova et al., 1998). These cytokines are involved in the induction and effector phases of EAE, notably in the recruitment of cells into the CNS and localized inflammatory and acute-phase responses in the brain (Merrill and Benveniste, 1996; Korner et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2002). The current study demonstrates that both 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 are able to inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. Many studies have shown already that 15d-PGJ2 is very effective in attenuating the expression of a number of proinflammatory cytokines from numerous sources, including rodent and human monocyte/macrophages (Jiang et al., 1998; Ricote et al., 1998; Thieringer et al., 2000; Guyton et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Alleva et al., 2002; Hinz et al., 2003) and rodent microglia (Bernardo et al., 2000; Koppal et al., 2000; Drew and Chavis, 2001). This is the first demonstration, however, of PGA2 inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production. In contrast to the relative effects on microglial NO production, PGA2 seems to be more effective than 15d-PGJ2 in downregulating proinflammatory cytokine production from activated microglial cells. This is surprising, considering the multifaceted actions that 15d-PGJ2 has on gene expression. For example, it is known that 15d-PGJ2 can alter DNA-binding activity of NF-κB and STAT-1, transcription factors that regulate the expression of proinflammatory genes, via PPAR-γ-independent mechanisms or via receptor-dependent transrepression (Kielian and Drew, 2003). It is possible that the actions of both cPGs on microglial cytokine expression are largely through the reactive carbonyl group. The mechanisms of action of PGA2 on cytokine expression are not known at this time, however, and represent an important avenue of further investigation.

The current study also shows that both 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 are effective in downregulating the expression of the β chemokine MCP-1 by microglia. MCP-1 is primarily chemoattractant for T cells and monocytes (Smeltz and Swanborg, 1998; Kennedy and Karpus, 1999); however, MCP-1 is chemoattractant for dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and microglia as well (Mahad and Ransohoff, 2003). MCP-1 has been implicated in MS based on its localization to astrocytes in active lesions, cerebrospinal fluid, and serum of affected patients (McManus et al., 1998; Simpson et al., 1998; Sorensen et al., 1999; Van Der Voorn et al., 1999; Franciotta et al., 2001). The inactivation of MCP-1 has demonstrated the importance of this chemokine in directing monocytes to areas of inflammation and its importance in amplification rather than initiation of EAE (Hulkower et al., 1993; Fuentes et al., 1995; Glabinski et al., 1995; Kennedy et al., 1998). Both cPGs were effective in inhibiting MCP-1 secretion; however, the effect of PGA2 on MCP-1 expression was greater than that of 15d-PGJ2. This correlates with the greater effect of PGA2 on inhibiting expression of the cytokines that we have examined. Cyclopentenone PGs are thus able to regulate the inflammatory response in part by regulating the expression of specific cytokines and chemokines from activated microglia.

In addition to the contribution of activated microglia, activated astrocytes also produce proinflammatory cytokines and NO that can lead to the pathology associated with MS (Becher et al., 2000; Dong and Benveniste, 2001; De Keyser et al., 2003). Additionally, the activation of astrocytes in the course of MS leads to the formation of astrocytic scarring in the chronic MS plaques that can produce an inhibitory environment and ultimately impede tissue repair (Zeinstra et al., 2000, 2003; Holley et al., 2003; Morcos et al., 2003). We thus examined the ability of the cPGs to alter the production of NO and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from activated astrocytes. We discovered that both 15d-PGJ2 and PGA2 were able to inhibit the production of NO, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 from astrocytes stimulated with LPS. Astrocytes express PPAR-γ, suggesting that 15d-PGJ2 may act at least in part through a PPAR-γ-dependent mechanism (Chattopadhyay et al., 2000; Cristiano et al., 2001; Klotz et al., 2003). Additionally, the ability of 15d-PGJ2 to alter cytokine gene expression of both microglia and astrocytes has been linked to the regulation of the JAK-STAT pathway via the upregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 and -3 (Park et al., 2003). One previous study demonstrated that the administration of 15d-PGJ2 was able to upregulate the expression of the neurotrophic factors nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by mouse primary astrocytes (Toyomoto et al., 2004), suggesting multiple avenues of therapeutic action of cPGs on astroglial cells.

The current studies indicate that 15d-PGJ2 inhibited NO production by microglia and astrocytes more potently than did PGA2. PGA2 is more potent than 15d-PGJ2, however, in suppressing production of the cytokines and chemokine that we investigated in these glial cells. This may suggest that these cPGs differentially regulate the expression of genes encoding iNOS and the cytokines and chemokine studied; however, further studies are required to determine the molecular mechanisms resulting in the differential expression of these proinflammatory molecules.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a novel function for PGA2 as a potent mediator of antiinflammatory activity in microglia. Furthermore, we have shown that the cPGs PGA2 and 15d-PGJ2 also inhibit production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by astrocytes. These results emphasize the importance of cPGs in the regulation of the immune response, and further suggest that these PGs may be effective in the treatment of neuroinflammatory disorders including MS.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; Contract grant number: RG 3198A1; Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: NS 042860, NS 047546.

References

- Alleva DG, Johnson EB, Lio FM, Boehme SA, Conlon PJ, Crowe PD. Regulation of murine macrophage proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: counter-regulatory activity by IFN-gamma. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:677–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher B, Prat A, Antel JP. Brain-immune connection: immunoregulatory properties of CNS-resident cells. Glia. 2000;29:293–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste EN. Role of macrophages/microglia in multiple sclerosis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Mol Med. 1997;75:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s001090050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo A, Ajmone-Cat MA, Levi G, Minghetti L. 15-deoxy-delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 regulates the functional state and the survival of microglial cells through multiple molecular mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2003;87:742–751. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo A, Levi G, Minghetti L. Role of the peroxisome proliferator--activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) and its natural ligand 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 in the regulation of microglial functions. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2215–2223. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan CF, Cannella B, Battistini L, Raine CS. Cytokine localization in multiple sclerosis lesions: correlation with adhesion molecule expression and reactive nitrogen species. Neurology. 1995;45(Suppl):16–21. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6_suppl_6.s16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui T, Straus DS. Effects of cyclopentenone prostaglandins and related compounds on insulin-like growth factor-I and Waf1 gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1397:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannella B, Raine CS. The adhesion molecule and cytokine profile of multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:424–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Chavis JA, Liu LZ, Drew PD. Cholesterol oxides induce programmed cell death in microglial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:817–821. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay N, Singh DP, Heese O, Godbole MM, Sinohara T, Black PM, Brown EM. Expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) in human astrocytic cells: PPAR gamma agonists as inducers of apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:67–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000701)61:1<67::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CW, Chang YH, Tsi CJ, Lin WW. Inhibition of IFN-gamma-mediated inducible nitric oxide synthase induction by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist, 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2, involves inhibition of the upstream Janus kinase/STAT1 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2003;171:979–988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristiano L, Bernardo A, Ceru MP. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) and peroxisomes in rat cortical and cerebellar astrocytes. J Neurocytol. 2001;30:671–683. doi: 10.1023/a:1016525716209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keyser J, Zeinstra E, Frohman E. Are astrocytes central players in the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis? Arch Neurol. 2003;60:132–136. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab A, Deng C, Smith JD, Hussain RZ, Phanavanh B, Lovett-Racke AE, Drew PD, Racke MK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2002;168:2508–2515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab A, Hussain RZ, Lovett-Racke AE, Chavis JA, Drew PD, Racke MK. Ligands for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and the retinoid X receptor exert additive anti-inflammatory effects on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Benveniste EN. Immune function of astrocytes. Glia. 2001;36:180–190. doi: 10.1002/glia.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew PD, Chavis JA. The cyclopentone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Delta(12, 14) prostaglandin J2 represses nitric oxide, TNF-alpha, and IL-12 production by microglial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;115:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein DL, Galea E, Gavrilyuk V, Brosnan CF, Whitacre CC, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Landreth GE, Pershadsingh HA, Weinberg G, Heneka MT. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:694–702. doi: 10.1002/ana.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenyk-Melody JE, Garrison AE, Brunnert SR, Weidner JR, Shen F, Shelton BA, Mudgett JS. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is exacerbated in mice lacking the NOS2 gene. J Immunol. 1998;160:2940–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciotta D, Martino G, Zardini E, Furlan R, Bergamaschi R, Andreoni L, Cosi V. Serum and CSF levels of MCP-1 and IP-10 in multiple sclerosis patients with acute and stable disease and undergoing immunomodulatory therapies. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;115:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes ME, Durham SK, Swerdel MR, Lewin AC, Barton DS, Megill JR, Bravo R, Lira SA. Controlled recruitment of monocytes and macrophages to specific organs through transgenic expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. J Immunol. 1995;155:5769–5776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willis D, Chivers J, Paul-Clark MJ, Willoughby DA. Inducible cyclooxygenase may have anti-inflammatory properties. Nat Med. 1999;5:698–701. doi: 10.1038/9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabinski AR, Tani M, Tuohy VK, Tuthill RJ, Ransohoff RM. Central nervous system chemokine mRNA accumulation follows initial leukocyte entry at the onset of acute murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:315–330. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton K, Bond R, Reilly C, Gilkeson G, Halushka P, Cook J. Differential effects of 15-deoxy-delta(12, 14)-prostaglandin J2 and a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist on macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Brune K, Pahl A. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12, 14)-prostaglandin J2 inhibits the expression of proinflammatory genes in human blood monocytes via a PPAR-gamma-independent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley JE, Gveric D, Newcombe J, Cuzner ML, Gutowski NJ. Astrocyte characterization in the multiple sclerosis glial scar. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:434–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulkower K, Brosnan CF, Aquino DA, Cammer W, Kulshrestha S, Guida MP, Rapoport DA, Berman JW. Expression of CSF-1, c-fms, and MCP-1 in the central nervous system of rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1993;150:2525–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl KG, Schmidt HH, Jung S, Sherman P, Toyka KV, Zielasek J. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice with a targeted deletion of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene: increased T-helper 1 response. Neurosci Lett. 2004;358:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahito Y, Kondo M, Tsubouchi Y, Hashiramoto A, Bishop-Bailey D, Inoue K, Kohno M, Yamada R, Hla T, Sano H. 15-deoxy-delta(12, 14)-PGJ(2) induces synoviocyte apoptosis and suppresses adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:189–197. doi: 10.1172/JCI9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KJ, Karpus WJ. Role of chemokines in the regulation of Th1/Th2 and autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:273–279. doi: 10.1023/a:1020535423465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KJ, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW, Karpus WJ. Acute and relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis are regulated by differential expression of the CC chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha and monocyte chemotactic protein-1. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;92:98–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian T, Drew PD. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists on central nervous system inflammation. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:315–325. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, Patel I, Morris DC, Lehmann JM. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L, Sastre M, Kreutz A, Gavrilyuk V, Klockgether T, Feinstein DL, Heneka MT. Noradrenaline induces expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma in murine primary astrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 2003;86:907–916. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal T, Petrova TV, Van Eldik LJ. Cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Delta(12, 14)-prostaglandin J(2) acts as a general inhibitor of inflammatory responses in activated BV-2 microglial cells. Brain Res. 2000;867:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner H, Riminton DS, Strickland DH, Lemckert FA, Pollard JD, Sedgwick JD. Critical points of tumor necrosis factor action in central nervous system autoimmune inflammation defined by gene targeting. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1585–1590. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutton JD, Winston R, Rodman TC. Multiple sclerosis: etiological mechanisms and future directions. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:12–20. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad DJ, Ransohoff RM. The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) Semin Immunol. 2003;15:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, McFarland HF, McFarlin DE. Immunological aspects of demyelinating diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:153–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus C, Berman JW, Brett FM, Staunton H, Farrell M, Brosnan CF. MCP-1, MCP-2 and MCP-3 expression in multiple sclerosis lesions: an immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;86:20–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Benveniste EN. Cytokines in inflammatory brain lesions: helpful and harmful. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcos Y, Lee SM, Levin MC. A role for hypertrophic astrocytes and astrocyte precursors in a case of rapidly progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9:332–341. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms931oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan C, Bright JJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists inhibit experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-12 production, IL-12 signaling and Th1 differentiation. Genes Immun. 2002;3:59–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi M, Katoh H. Cyclopentenone prostaglandin receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Park SY, Joe E, Jou I. 15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone suppress Janus kinase-STAT inflammatory signaling through induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) and SOCS3 in glia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14747–14752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova TV, Akama KT, Van Eldik LJ. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins suppress activation of microglia: down-regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4668–4673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahrbacher UC, Lechner F, Eugster HP, Frei K, Lassmann H, Fontana A. Mice with an inactivation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene are susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1332–1338. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199804)28:04<1332::AID-IMMU1332>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoilova EB, Horton JL, Hilliard B, Liu TS, Chen Y. IL-6-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: roles of IL-6 in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6480–6486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JE, Newcombe J, Cuzner ML, Woodroofe MN. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and other beta-chemokines by resident glia and inflammatory cells in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;84:238–249. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeltz RB, Swanborg RH. Concordance and contradiction concerning cytokines and chemokines in experimental demyelinating disease. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:147–153. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980115)51:2<147::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen TL, Tani M, Jensen J, Pierce V, Lucchinetti C, Folcik VA, Qin S, Rottman J, Sellebjerg F, Strieter RM, Frederiksen JL, Ransohoff RM. Expression of specific chemokines and chemokine receptors in the central nervous system of multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:807–815. doi: 10.1172/JCI5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. Myelin-specific CD8 T cells in the pathogenesis of experimental allergic encephalitis and multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:27–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.f27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinissen P, Medaer R, Raus J. Myelin reactive T cells in the autoimmune pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1998;4:203–211. doi: 10.1177/135245859800400322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus DS, Glass CK. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins: new insights on biological activities and cellular targets. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:185–210. doi: 10.1002/med.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus DS, Pascual G, Li M, Welch JS, Ricote M, Hsiang CH, Sengchanthalangsy LL, Ghosh G, Glass CK. 15-deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits multiple steps in the NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4844–4849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su CG, Wen X, Bailey ST, Jiang W, Rangwala SM, Keilbaugh SA, Flanigan A, Murthy S, Lazar MA, Wu GD. A novel therapy for colitis utilizing PPAR-gamma ligands to inhibit the epithelial inflammatory response. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:383–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI7145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer R, Fenyk-Melody JE, Le Grand CB, Shelton BA, Detmers PA, Somers EP, Carbin L, Moller DE, Wright SD, Berger J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma does not inhibit IL-6 or TNF-alpha responses of macrophages to lipopolysaccharide in vitro or in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:1046–1054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyomoto M, Ohta M, Okumura K, Yano H, Matsumoto K, Inoue S, Hayashi K, Ikeda K. Prostaglandins are powerful inducers of NGF and BDNF production in mouse astrocyte cultures. FEBS Lett. 2004;562:211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen RC, Dietlin TA, Hofman FM. Tissue expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase requires IFN-gamma production by infiltrating splenic T cells: more evidence for immunosuppression by nitric oxide. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;145:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Voorn P, Tekstra J, Beelen RH, Tensen CP, Van Der Valk P, De Groot CJ. Expression of MCP-1 by reactive astrocytes in demyelinating multiple sclerosis lesions. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65249-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Asensio VC, Campbell IL. Cytokines and chemokines as mediators of protection and injury in the central nervous system assessed in transgenic mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;265:23–48. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-09525-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenborg DO, Staykova MA, Cowden WB. Our shifting understanding of the role of nitric oxide in autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a review. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao BG, Link H. Antigen-specific T cells in autoimmune diseases with a focus on multiple sclerosis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:5–21. doi: 10.1007/s000180050002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SS, Wu ZY, Zhang HP, Furtado G, Chen X, Yan SF, Schmidt AM, Brown C, Stern A, LaFaille J, Chess L, Stern DM, Jiang H. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by selective blockade of encephalitogenic T-cell infiltration of the central nervous system. Nat Med. 2003;9:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeinstra E, Wilczak N, De Keyser J. Reactive astrocytes in chronic active lesions of multiple sclerosis express co-stimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;135:166–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeinstra E, Wilczak N, Streefland C, De Keyser J. Astrocytes in chronic active multiple sclerosis plaques express MHC class II molecules. Neuroreport. 2000;11:89–91. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang JM, Gong WH, Mukaida N, Young HA. Differential regulation of chemokine gene expression by 15-deoxy-delta 12, 14 prostaglandin J2. J Immunol. 2001;166:7104–7111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]