Abstract

The basic reproduction number, R0, a summary measure of the transmission potential of an infectious disease, is estimated from early epidemic growth rate, but a likelihood-based method for the estimation has yet to be developed. The present study corrects the concept of the actual reproduction number, offering a simple framework for estimating R0 without assuming exponential growth of cases. The proposed method is applied to the HIV epidemic in European countries, yielding R0 values ranging from 3.60 to 3.74, consistent with those based on the Euler-Lotka equation. The method also permits calculating the expected value of R0 using a spreadsheet.

Keywords: transmission, infectious diseases, basic reproduction number, epidemiology, statistical model, estimation techniques, HIV, AIDS

1. Introduction

1.1. The Basic Reproduction Number

The basic reproduction number, R0, of an infectious disease is the average number of secondary cases generated by a single primary case in a fully susceptible population [1]. R0 is the most widely used epidemiological measurement of the transmission potential in a given population. Statistical estimation of R0 has been performed for various infectious diseases [2,3], aiming towards understanding the dynamics of transmission and evolution, and designing effective public health intervention strategies. In particular, R0 has been used for determining the minimum coverage of immunization, because the threshold condition to prevent a major epidemic in a randomly-mixing population is given by 1-1/R0 [4]. In addition, R0 gives an estimate of the so-called final size, i.e., the proportion of the population that will experience infection by the end of an epidemic [5,6].

1.2. Statistical Estimation of R0

Methodological discussions concerning the statistical inference of R0 are still in progress, and it is recognized that the estimate is very sensitive to dispersal (or underlying epidemiological assumptions) of the progression of a disease [7]. When one estimates R0 using epidemic data of an emerging (or exotic) disease, the exponential growth rate, r, of infections during the initial phase of the epidemic is used [8,9]. Assuming that the generation time, i.e., the time from infection of a primary case to infection of a secondary case generated by the primary case [10], is known (or separately estimated from other empirical data), the growth rate r is transformed to R0 using that knowledge (see below). That is, the conventional estimation technique has required two statistical steps, namely, first estimate r and then convert r to R0.

The estimation method can be illustrated by employing a simple renewal process which adheres to the original definition of R0 [1]. Let j(t) be the number of new infections (i.e., incidence) at calendar time t. Supposing that each infected individual on average generates secondary cases at a rate A(τ) at time τ since infection (where τ is referred to as the “infection-age” hereafter), j(t) is written as:

| (1) |

Since R0 represents the total number of secondary cases that a primary case generates during the entire course of infection, the estimate is given by ([11]):

| (2) |

When j(t) follows an exponential growth path, it is easy to extract the integral of A(τ) from equation (1). Supposing that the incidence grows exponentially at a rate r, we have j(t) = kexp(rt) where k is a constant, and moreover, j(t – τ) = kexp(rt)exp(–rτ). This simplifies (1) to the so-called Euler-Lotka equation:

| (3) |

Since the density function of the generation time, g(τ), represents the frequency of secondary transmissions relative to infection-age τ, we can write g(τ) as:

| (4) |

Replacing A(τ) in the right-hand side of (3) by that of (4), an estimator of R0 is obtained [9]:

| (5) |

The estimation of R0 is achieved by measuring the exponential growth rate r from the incidence data and also by assuming that g(τ) is known (or separately estimated from empirical observation such as contact tracing data [12,13]). It should be noted that the above mentioned framework has not been given a likelihood-based method for estimating R0 (i.e., a likelihood function used for fitting a statistical model to data, and providing estimates for R0, has been missing). Moreover, equation (5) may not be easily used by non-experts, e.g., an epidemiologist who wishes to estimate R0 using her/his own data.

The purpose of the present study is to offer an improved framework for estimating R0 from early epidemic growth data, which may be slightly more tractable among non-experts as compared with the above mentioned estimator (5). A likelihood-based approach is proposed to permit derivation of the uncertainty bounds of R0. For an exposition of the proposed method, the incidence data of the HIV epidemic in Europe is explored.

2. Methods

2.1. Actual Reproduction Number

In addition to R0, a different measurement of the transmission potential using widely available epidemiological data, the actual reproduction number, Ra, has been proposed for HIV/AIDS [14]. The concept of Ra is much simpler than R0 in that Ra is defined as a product of the mean duration of infectiousness and the ratio of incidence to prevalence [15]. The prevalence p(t) at calendar time t is written as:

| (6) |

where Γ(τ) is the survivorship of infectiousness, or probability of being infectious, at infection-age τ. Letting β(τ) be the transmission rate, which depends primarily on the frequency of contact and infectiousness at infection-age τ, the above mentioned A(τ), the rate of secondary transmission per single primary case at τ, under an assumption of a Kermack and McKendrick type model, is decomposed as ([16]):

| (7) |

The actual reproduction number Ra is written as:

| (8) |

where D is the mean generation time (or what was previously described as the mean duration of infectiousness [14,15]). If the transmission rate β(τ) is constant β (i.e., independent of infection-age), Ra = βD. Moreover, from equation (2)R0 is given by:

| (9) |

Ra coincides with R0 as long as β(τ) is constant. Nevertheless, in many instances, the contact frequency and infectiousness (which may be partly reflected, for example, in the viral load distribution of the infected host) vary as a function of infection-age τ. The variation in β(τ) is particularly the case for HIV infection. Thus, although the usefulness of the incidence-to-prevalence ratio and Ra has been emphasized to have an application in HIV/AIDS [15], Ra tends to yield a biased estimate (if Ra is regarded as a proxy for R0), and the estimate of Ra is not as robust as that is obtained with equation (5) to objectively interpret the transmission potential [17,18].

2.2. Correcting Ra

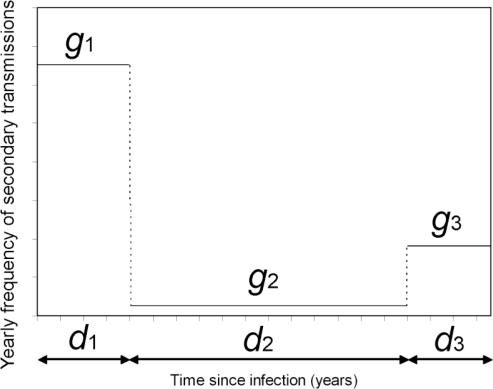

Here, the above mentioned negative aspect of Ra is reconsidered by correcting the definition of Ra. The disease of interest in the present study is HIV. The frequency of secondary transmissions relative to infection-age τ (i.e., the generation time distribution), approximated by a step function, is shown in Figure 1. As has been known for some time [19], the frequency of secondary transmissions is very high shortly after infection (for a duration d1 = 0.24 years), followed by a long asymptomatic period with a low frequency of secondary transmissions (for d2 = 8.38 years) [20]. Subsequently, the frequency rises sharply again resulting in a substantial number of secondary cases for a duration d3 = 0.75 years until death or until the infected individual ceases risky sexual contact due to AIDS [20–22]. Assuming that the contact frequency does not vary as a function of infection-age, g1, g2 and g3 have been estimated at 1.30, 0.05 and 0.36 per year [20]. Here, g(τ) is the density function of the generation time, with a mean of 3.79 years.

Figure 1.

The relative frequency of secondary transmissions of HIV as a function of the time since infection. A step function is employed to approximately model the frequency of secondary transmissions relative to infection-age. For d1 years shortly after infection, the frequency g1 is very high. Subsequently, for d2 years (i.e., during the asymptomatic period), g2 is persistently low, followed by a time period with high infectiousness g3 for d3 years until death or no secondary transmission due to AIDS. Following a statistical study [20], d1, d2 and d3 are assumed to be 0.24, 8.38 and 0.75 years. Assuming that the contact frequency does not vary as a function of time since infection, g1, g2 and g3 are estimated at 1.30, 0.05 and 0.36 per year.

Here the concept of Ra is corrected. The equation (8) is rewritten as:

| (10) |

The numerator represents the number of new infections at calendar time t, while the denominator was originally intended to represent “the total number of infectious individuals” who can potentially be primary cases with an equal chance at time t. Nevertheless, in order that the estimator of the actual reproduction number coincides with that of R0, the concept of the denominator is better replaced by “the total number of effective contacts (which can potentially lead to secondary transmissions with an equal probability)”. Therefore, the corrected Ra is better written as:

| (11) |

where g(τ), in the renewal equation with the Kermack and McKendrick type assumption, is written as the normalized density of secondary transmissions, i.e.,:

| (12) |

Replacing g(τ) in the right-hand side of (11) by that of (12), we get:

| (13) |

Thus, the estimator of corrected Ra in (11) is identical to that of R0. In other words, R0 can be estimated from the incidence data and the generation time without assuming exponential growth of cases during the early phase of an epidemic. It should be noted that the ratio of prevalence to mean generation time p(t)/D in the denominator of the right-hand side of (10) has been replaced by “the total number of effective contacts that have equal potential to generate secondary cases”.

2.3. Data

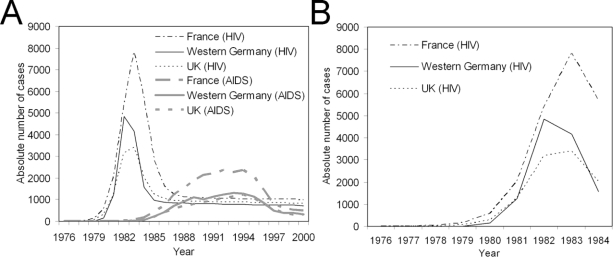

Here the epidemic data of HIV/AIDS in three European countries: France, the Western part of Germany (i.e., the former Western Germany) and the United Kingdom (UK) are investigated [23]. Figure 2A shows the yearly incidence in these countries from 1976–2000. During the observation period, a total of 23,243, 13,126 and 11,491 AIDS cases were diagnosed in France, Western Germany and the UK, respectively. Although the time of HIV infection is not directly observable, the HIV incidence has been estimated by employing a back-calculation technique and using the AIDS incidence and the incubation period distribution of AIDS [23]. The present study does not discuss the details of back-calculation, but explanatory guides can be found elsewhere [24–26]. Figure 2B shows the enlarged HIV incidence curve during the initial phase of an epidemic. The peak incidence was observed in 1982 for Western Germany and 1983 for France and the UK. In the following, the time period from 1976 up to one year prior to the peak incidence is taken as the early growth phase. For the purpose of an exposition of the proposed method, the HIV incidence is assumed to have been in a single homogeneously-mixing population.

Figure 2.

Epidemic curves of HIV/AIDS in France, Western Germany and the United Kingdom (UK) from 1976–2000. A. The yearly number of new HIV infections (i.e., incidence) and new AIDS cases from 1976–2000. AIDS cases are the observed data, while HIV incidence is estimated by means of a back-calculation method used by Artzrouni [23]. B. The early growth phase of the HIV epidemic. The peak incidence was observed in 1982 in Western Germany and 1983 in France and the UK.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

R0 is estimated using two different methods, one employing the estimator (5) and another using the corrected Ra. For the former approach, the exponential growth rate is estimated via a pure birth process [27]. Given that the cumulative incidence from year 0 to t – 1 is observed, the conditional likelihood of observing the cumulative incidence Jt cases in year t is proportional to ([28]):

| (14) |

from which the maximum likelihood estimate and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of r (per year) are obtained. Given a fixed generation time distribution g(τ), the uncertainty bound of R0 mirrors the uncertainty in the estimate of r. The translation of r into R0 via (5) is made by using g(τ) in Figure 1.

The latter method, proposed in the present study, employs the estimator of corrected Ra in (11). Since the data are yearly, the equation (11) needs to be rewritten in discrete-time:

| (15) |

where the discrete density function of the generation time, gs is assumed to be given by gs = G(s + 1) – G(s), where G(s) is the cumulative distribution function of the generation time of length s, but g0 is calculated as a normalized yearly average, because d1 is as short as 0.24 years.

The likelihood of estimating R0 with (15) is proposed as follows. First, the inverse of both sides of (15) is taken:

| (16) |

The numerator of the right-hand side indicates the total number of effective contacts made by potential primary cases in year t that have an equal probability of resulting in a secondary transmission, and the denominator is the number of secondary cases in year t.

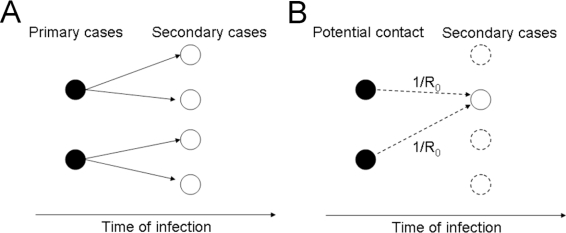

The right-hand side of equation (16) is interpreted as follows. Figure 3A shows a transmission tree, i.e., a representation of who infected whom, where each primary case on average generates two secondary cases. A transmission tree of this kind is usually unobserved unless rigorous contact-tracing with microbiological examination is implemented. Thus, a likelihood-based approach to reconstructing the tree is considered (Figure 3B) [29–31]. Given the total number of effective contacts that have equal potential for resulting in secondary transmission, the probability of a single effective contact resulting in a secondary transmission (or the probability that a secondary case is linked to an effective contact made by a single primary case in year t) is given by 1/R0. This is a simple binomial sampling process. In other words, the likelihood function for estimating R0 is:

| (17) |

where T is the most recent time point of observation within an early (linear) epidemic growth stage. The maximum likelihood estimate of R0 is obtained by minimizing the negative logarithm of (17), and the 95% CI are derived from the profile likelihood.

Figure 3.

The transmission tree with R0 = 2. (A) Black circles represent primary cases that are infectious to others at time t and white circles are secondary cases generated by the primary cases. Secondary transmissions from primary to secondary cases are given with the basic reproduction number, R0 = 2, i.e., each primary case generates two secondary cases. (B) Reconstruction of the transmission tree. Given that all the potential contacts made by primary cases (black circles) are known using the incidence data and the generation time distribution, the probability that each potential contact resulted in a secondary transmission is given by 1/R0.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows the estimates of r and R0 for HIV in France, Western Germany and the UK. The maximum likelihood estimates of r ranged from 1.15 to 2.15 per year with the smallest estimate in France and the highest in Western Germany. The 95% CI for Western Germany did not overlap with those of the other two countries, reflecting the steep rise in incidence in this region in Figure 2B. Based on the exponential growth assumption in (5), the estimate of R0 ranged from 3.65–4.08. Again, Western Germany yielded the highest estimate without an overlap of the uncertainty bound with the other two countries. The maximum likelihood estimate of R0 based on the proposed new method ranged from 3.59 to 3.74. Not only were the qualitative patterns for the expected values of R0 consistent with those based on an exponential growth assumption, but the 95% CI also broadly overlapped with those based on the other method. In particular, although R0 in Western Germany using the proposed method is smaller than that based on an exponential growth assumption, the 95% CIs of the two methods overlapped. The 95% CI based on the proposed method appeared to be wider than those based on exponential growth assumption. Since HIV is mainly transmitted via sexual contact, the above mentioned estimate may vary with the mixing pattern and contact frequency (thus, there is no general disease-specific R0, especially for HIV/AIDS). At least, compared with a previous estimate of R0 as ranging from 13.9 to 54.5 in the USA, based on an exponential growth assumption that adopted a mean infectious period of 10 years [32], R0 in the present study appeared to be much smaller using a precise estimate of the generation time distribution.

Table 1.

Comparison of the estimates of the basic reproduction number for HIV/AIDS obtained using two different estimation methods.

| Country | r (/year)1 | R0 (exponential growth) 2 | R0 (proposed likelihood) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 1.15 (1.12, 1.17) | 3.65 (3.64, 3.66) | 3.59 (3.38, 3.81) |

| Western Germany | 2.15 (2.02, 2.29) | 4.08 (4.02, 4.14) | 3.74 (3.43, 4.08) |

| UK | 1.21 (1.18, 1.25) | 3.67 (3.66, 3.69) | 3.65 (3.38, 3.96) |

The intrinsic growth rate during the exponential growth phase;

the basic reproduction number estimated using equation (5);

the basic reproduction number estimated using equation (17); the 95% confidence intervals are shown in parentheses.

The present study proposed the use of the corrected actual reproduction number, Ra, for statistical inference of R0 based on incidence and known relative frequency of secondary transmissions (i.e., the generation time distribution) during the early growth phase of an epidemic. The previously available method using (5) forced us to adopt an exponential growth assumption, and moreover, an additional step towards the estimation of r (i.e., the translation of r to R0) was required [9]. The proposed method does not necessarily require an exponential growth assumption and provides a “short-cut” to estimate R0 from incidence data. The simple likelihood function employing a binomial distribution was also proposed to yield an appropriate uncertainty bound of R0. It should be noted that given the knowledge of gs and readily available incidence data, equation (15) permits calculation of the expected value of R0 without likelihood. Such a calculation can be attained using any spreadsheet.

The usefulness of the actual reproduction number, calculated as a product of the mean generation time and the incidence-to-prevalence ratio, has been previously emphasized in assessing the epidemiological time course of an epidemic [14,15]. However, it appears that Ra does not precisely capture the secondary transmission if the transmission rate β(τ) varies with infection-age τ [18], and moreover, the cohort- and period-reproduction numbers directly derived from the renewal equation have been suggested to be more accurate figures in capturing the underlying transmission dynamics [17,33]. In the present study, replacing the denominator (i.e., prevalence) of Ra by the total number of potential contacts, it was shown that the R0 derived from the renewal equation coincides with the corrected actual reproduction number, Ra, and also that the likelihood can be quite easily derived. The corrected Ra does not require prevalence data, and uses only the incidence data and the generation time distribution.

Many future tasks remain, however. Most importantly, the estimation of R0 from early epidemic growth data for a heterogeneously-mixing population is called for. R0 in the present study can even be interpreted as R0 for a heterogeneously-mixing population (i.e., the dominant eigenvalue of the next-generation matrix), provided that the early growth rate is the same among sub-populations (though it is not the case if the growth rate varies across sub-populations) [34,35]. Analyzing heterogeneous transmission among approximately-aggregated discrete groups, the estimate of the next-generation matrix would give more detailed insights into the epidemic dynamics, including the most important target host for intervention [36]. As discussed in a modeling study in this special issue of the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [37], understanding the implications of sexual partnerships and their variations as a function of calendar time as well as infection-age is also of utmost importance. As the next step for a similar estimation framework, methods for estimating robust R0 and the next-generation matrix from structured data (i.e., data stratified by age- and/or risk-groups) will be useful. Despite the future challenges, I believe the present study at least satisfies a need to offer a likelihood-based approach to estimate R0 from early epidemic growth data, while being easily tractable and calculable among general epidemiologists.

Acknowledgments

The work of H. Nishiura was supported by the JST PRESTO program.

References

- 1.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JA, Metz JA. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990;28:365–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz K. The estimation of the basic reproduction number for infectious diseases. Stat. Methods. Med. Res. 1993;2:23–41. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker NG. Analysis of Infectious Disease Data. Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CE. Factors in the transmission of virus infections from animal to man. Sci Basis Med Ann Rev. 1964:125–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall DG. Proceedings of the 3rd Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA, USA: 1956. Deterministic and stochastic epidemics in closed populations; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J, Earn DJ. Generality of the final size formula for an epidemic of a newly invading infectious disease. Bull. Math. Biol. 2006;68:679–702. doi: 10.1007/s11538-005-9047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heffernan JM, Wahl LM. Improving estimates of the basic reproductive ratio: using both the mean and the dispersal of transition times. Theor. Pop. Biol. 2006;70:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massad E, Coutinho FA, Burattini MN, Amaku M. Estimation of R0 from the initial phase of an outbreak of a vector-borne infection. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2009;15:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallinga J, Lipsitch M. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lon. Ser. B. 2007;274:599–604. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svensson A. A note on generation times in epidemic models. Math. Biosci. 2007;208:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JAP. Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building, Analysis and Interpretation. John Wiley & Son; Chichester, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garske T, Clarke P, Ghani AC. The transmissibility of highly pathogenic avian influenza in commercial poultry in industrialised countries. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White LF, Pagano M. A likelihood-based method for real-time estimation of the serial interval and reproductive number of an epidemic. Stat. Med. 2008;27:2999–3016. doi: 10.1002/sim.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amundsen EJ, Stigum H, Rottingen JA, Aalen OO. Definition and estimation of an actual reproduction number describing past infectious disease transmission: application to HIV epidemics among homosexual men in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004;132:1139–1149. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White PJ, Ward H, Garnett GP. Is HIV out of control in the UK? An example of analysing patterns of HIV spreading using incidence-to-prevalence ratios. AIDS. 2006;20:1898–1901. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000244213.23574.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chowell G, Nishiura H. Quantifying the transmission potential of pandemic influenza. Phys. Life. Rev. 2008;5:50–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser C. Estimating individual and household reproduction numbers in an emerging epidemic. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishiura H, Chowell G. The effective reproduction number as a prelude to statistical estimation of time-dependent epidemic trends. In: Chowell G, Hyman JM, Bettencourt LMA, Castillo-Chavez C, editors. Mathematical and Statistical Estimation Approaches in Epidemiology. Springer; Dordrecht, Germany: 2009. pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiboski SC, Jewell NP. Statistical analysis of the time dependence of HIV infectivity based on partner study data. J. Amer. Statist. Assn. 1991;87:360–372. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollingsworth TD, Anderson RM, Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:687–693. doi: 10.1086/590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, Kiwanuka N, Kigozi G, Kiddugavu M, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan MP, Quinn TC. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Raddad LJ, Longini IM. No HIV stage is dominant in driving the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1055–1061. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f8af84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artzrouni M. Back-calculation and projection of the HIV/AIDS epidemic among homosexual/bisexual men in three European countries: Evaluation of past projections and updates allowing for treatment effects. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2004;19:171–179. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000017826.57607.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brookmeyer R, Gail MH. AIDS Epidemiology: A Quantitative Approach (Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics) Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jewell NP, Dietz K, Farewell VT. AIDS Epidemiology: Methodological Issues. Birkhäuser; Berlin, Germany: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishiura H. Lessons from previous predictions of HIV/AIDS in the United States and Japan: epidemiologic models and policy formulation. Epidemiol. Perspect. Innov. 2007;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey NTJ. The Elements of Stochastic Processes with Applications to the Natural Sciences. Wiley; New York, NY, USA: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiura H, Castillo-Chavez C, Safan M, Chowell G. Transmission potential of the new influenza A(H1N1) virus and its age-specificity in Japan. Euro. Surveill. 2009;14:19227. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.22.19227-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallinga J, Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Amer. J. Epidemiol. 2004;160:509–516. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haydon DT, Chase-Topping M, Shaw DJ, Matthews L, Friar JK, Wilesmith J, Woolhouse ME. The construction and analysis of epidemic trees with reference to the 2001 UK foot-and-mouth outbreak. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lon. Ser. B. 2003;270:121–127. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishiura H, Schwehm M, Kakehashi M, Eichner M. Transmission potential of primary pneumonic plague: time inhomogeneous evaluation based on historical documents of the transmission network. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:640–645. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacquez JA, Simon CP, Koopman JS. The reproduction number in deterministic models of contagious diseases. Comments Theor. Biol. 1991;2:159–209. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grassly NC, Fraser C. Mathematical models of infectious disease transmission. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:477–487. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishiura H, Chowell G, Heesterbeek H, Wallinga J. The ideal reporting interval for an epidemic to objectively interpret the epidemiological time course. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7:297–307. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishiura H, Chowell G, Safan M, Castillo-Chavez C. Pros and cons of estimating the reproduction number from early epidemic growth rate of influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2010;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hethcote HW, Yorke JA. Gonorrhea Transmission Dynamics and Control (Lecture Notes in Biomathematics, 56) Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller H, Bauch C.When do sexual partnerships need to be accounted for in transmission models of human papilloma virus Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010. submitted [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]