Abstract

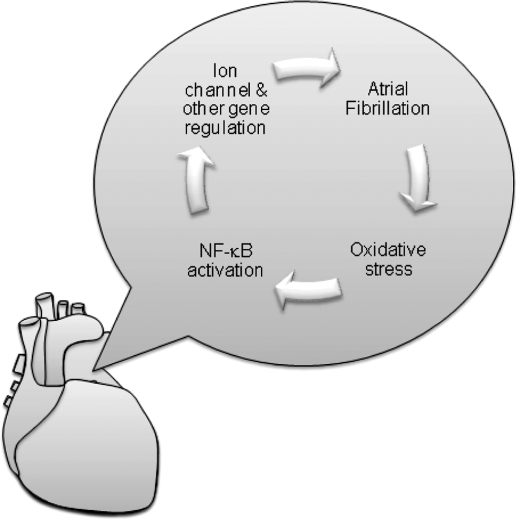

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinically encountered abnormal heart beat. It is associated with an increased risk of stroke and symptoms of heart failure. Current therapies are directed toward controlling the rate of ventricular activation and preventing strokes through anticoagulation. Attempts at suppressing the arrhythmia are often ineffective, in part because the underlying pathogenesis is poorly understood. Recently, structural and electrical remodeling has been shown to occur during AF. These changes involve alterations in gene regulation and help perpetuate the arrhythmia. Some signals for remodeling are have been identified. Moreover, AF is associated with oxidative stress, and this redox imbalance may contribute to the altered gene regulation. One likely mediator of this change in transcriptional regulation is the redox sensitive transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). Recently, NF-κB has been shown to downregulate transcription of the cardiac sodium channel in response to oxidative stress. NF-κB may contribute to the regulation of other ion channels, transcription factors, or splicing factors altered in AF and may represent a therapeutic target in AF management. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2265–2277.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) was described more than a century ago (110). The clinical significance of AF and its related arrhythmia, atrial flutter, continues to amplify because of the increasing incidence of the disease and the associated morbidity and mortality, including cerebrovascular accidents (2). AF is the most common clinically encountered arrhythmia, and results from rapid, continuous electrical activity in the upper atria chambers of the heart associated with reduced effectiveness of atrial blood delivery to the ventricles. The consequences are rapid ventricular contraction, and blood pooling in the atria. The former leads to symptoms of heart failure. The latter can result in strokes if the blood clots embolize to the brain (12).

The prevalence of AF is 0.4–1.0% in the general US population, and this number is increasing yearly (58). AF is associated with other common cardiac conditions such as heart failure (96) and hypertension (62). Currently, the management of AF includes ventricular rate control and rhythm control strategies (4). In the rhythm control strategy, antiarrhythmic drugs are a mainstay for maintenance of sinus rhythm. Nevertheless, their use is limited by suboptimal efficacy and the risk of adverse effects, including induction of other arrhythmias, a result known as pro-arrhythmia (111). Other therapies include surgical and intracardiac therapy (23) to limit the available tissue to support the continuous electrical activity. Ablative therapy has incomplete efficacy and a number of complications (25). Moreover, complications of either antiarrhythmic or ablative therapies have constrained their use predominantly to patients with known AF, leaving patients without acceptable primary prevention strategies.

One characteristic of AF is that it is self-perpetuating, suggesting involvement of a positive feedback loop. Therefore, the longer one has AF, the harder it is to treat (104). Because it is hard to predict the onset of AF, most studies have focused on the changes happening upon AF generation, knowing that they are likely to contribute to the maintenance of the arrhythmia and hoping that mechanisms of initiation may be similar. Extensive efforts have gone into describing this disease and its consequences, and progress has been made in understanding the mechanism of AF (12). In the last decade or so, studies have made increasing use of molecular and proteomic techniques, leading to identification of molecules and genes altered during AF (101). Genetic regulation occurring during AF includes alterations in the total amount of encoding messenger RNA (mRNA) (56, 103) and abnormal mRNA splicing (97). These results hint that transcriptional regulation may play a key role in the mechanism of AF. The pathways signaling changes in transcriptional regulation during AF remain largely unknown, but there are some promising leads that may allow for future therapeutic interventions to treat AF (30, 95, 98).

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a key transcription regulator, coupling redox state to alterations in gene transcriptional regulation in such states as injury and inflammation stress (28), so it seems possible that NF-κB may mediate some of the transcriptional changes seen in AF (95, 98). In this review, we will explore the role of altered redox signaling, especially changes related to NF-κB, in the pathogenesis of AF. Hopefully, examination of the signaling pathways involved in AF will allow for treatment strategies that might be more effective and associated with less toxicity than current therapies based largely on ion channel blockade or ablation of atrial tissue.

The Evidence of Genetic Influences and Gene Regulation in AF

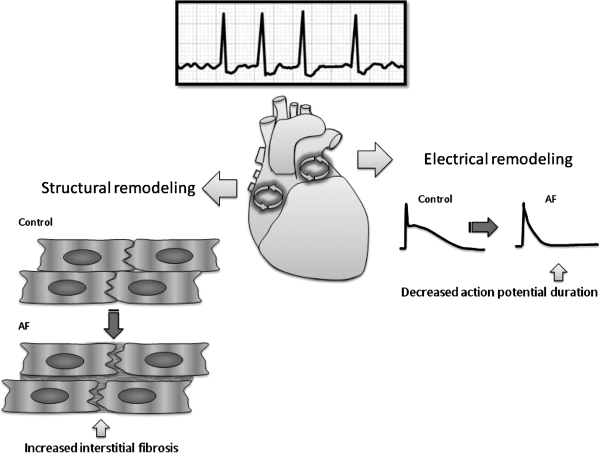

Multiple experimental studies have shown that the presence of AF leads to alterations in gene regulation (59, 114). These changes are likely to form part of the positive feedback loop that perpetuates AF (Fig. 1). These changes have been divided into two main categories: electrical and structural remodeling (8). The electrical remodeling is characterized by shortening of the atrial action potential duration and a loss of the rate-related decrease of the action potential duration that usually occurs with increasing heart rate (104). Fibrosis is a central feature in structure remodeling (66). Both electrical and structural remodeling have been implicated in the generation of multiple atrial electrical wavelets that characterize the continuous electrical activity present in AF.

FIG. 1.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) results in structural remodeling and electrical remodeling that contribute to the perpetuation of the arrhythmia. AF is caused by circus electrical activity in the atria and manifest by continuous low voltage fluctuations on the surface electrocardiogram with irregular conduction to the ventricle initiating the larger QRS deflections. Structural remodeling is characterized by increased fibrosis, and electrical remodeling is characterized by a shortening of the action potential duration.

Classically, there are two basic mechanisms of arrhythmia: enhanced focal activity in the form of enhanced automaticity or triggered arrhythmias and multicellular, continuous activity in the form of rotors or reentrant circuits. Rotors and reentry are favored by slow conduction, establishing a relationship between tachyarrhythmias and conduction defects. Conduction velocity is strongly influenced by the degree of cell–cell coupling and by Na+ channel availability, the main source of transmembrane current (51).

Ion channel transcriptional regulation is implicated in increasing ventricular and atrial arrhythmic risk (116). Often referred to as electrical remodeling, the changes in myocyte electrical properties in states of increased arrhythmic risk are related to underlying changes in expression of several ion channel genes, including reductions in connexins, the channels connecting heart cells, and Na+ channels (79, 116).

Several major signal pathways have been proposed to be involved in remodeling on the basis of experimental animal models and human studies (49, 80). Oxidative stress and inflammatory processes, angiotensin II (AngII) (82, 100), and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) (11, 65) are thought to influence AF-induced fibrosis. Among others, they regulate signaling pathway intermediaries such as the NADPH oxidase, MAP kinases, and NF-κB (64, 98).

Clues to which genes may be important in regulating the proclivity for AF come from studies of families predisposed to the arrhythmia (101). By using linkage analysis, several loci have been implicated in AF risk, including 11p15.5, 21q22, 17q, 7q35-36, 5p13, 6q14–16, and 10q22. Some of these loci encode subunits of cardiac potassium channels (KCNQ1, KCNE2, KCNJ2, and KCNH2 genes), and the remaining are as yet unidentified (101). Potassium channels are central to the establishment of the resting membrane potential and for the repolarization of the cell after an action potential. It appears that either an increase or decrease in potassium channel activity can affect AF risk. Association studies have linked several other genes to AF risk. These genes including those encoding potassium or sodium channels (SCN5A) (95, 97, 98), structural proteins such as sarcolipin (16), renin-angiotensin system (RAS) regulators (102), genes that control cell coupling (46), oxidative stress related genes (49), and inflammatory mediators (61).

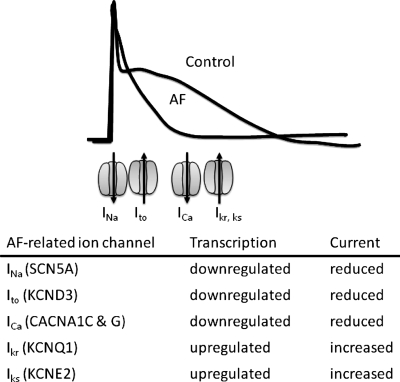

Many of the genes suggested to be important from inheritance studies have been evaluated in acquired, nonhereditary AF. Although results have conflicted at times, messenger RNA (mRNA) for the L-type Ca2+ and Ito potassium channels appear reduced in most models (37, 57). Humans with persistent AF have significant decreases ranging from 49% to 60% in mRNA encoding L-type Ca2+ channel α1c subunits, as measured by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Corresponding reductions in channel protein are apparent on immunoblots, and radiolabeled L-type Ca2+ channel blockers, the dihydropyridines, show reduced receptor binding (15, 21). These observations of reductions in mRNA abundance and protein imply transcriptional downregulation as a molecular mechanism of tachycardia-induced changes in atrial ion channel expression and electrical remodeling (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Ion channel transcriptional events underlie part of the action potential shortening associated with atrial fibrillation (AF). Representative action potentials in AF and control are shown. Some of the ion channels contributing to the various currents during the action potential are indicated. INa, Ito, ICa, Ikr, Iks stand for the sodium, transient outward, calcium, rapid delayed rectifier potassium, and slow delayed rectifier potassium currents, respectively. The relative position of the ion channels indicates the timing of their major activity during the action potential. Gene names encoding these currents are indicated in the parentheses.

The effects of AF are selective, suggesting that specific signaling pathways are involved. The mRNA abundances encoding for the human Ether-a-go-go Related Gene (hERG; KCNH2) product, a K+ channel active in the late action potential, and the inward rectifier K+ channel (KCNJ2), which determines the resting membrane potential, are unchanged by atrial tachycardia (48). Expression levels of Na+-Ca2+-exchanger, calsequestrin, phospholamban, and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channel mRNA are unaltered (16).

Gene comparison profiling between AF and controls show that transcriptional factors are altered in AF (49). Some transcription factors altered include FOS/v-fos (FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog), GTF2H2 (general transcription factor IIH, polypeptide 2), EGR2 (early growth response, Krox-20 homolog, Drosophila), PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), four and a half LIM domains protein-1 (FHL1) (20), and cardiac ankyrin repeat protein (CARP) (20). Among these, Fos/c-fos and PPARγ (19, 20) are known involved in redox signaling.

Whereas the signaling pathways for remodeling during AF are a matter of active investigation, recent evidence suggest that AF is associated with cardiac and systemic oxidation (52) that may serve as one signal amenable to targeted amelioration.

Evidence of Redox Alterations in AF

AF has been associated with myocardial and systemic oxidative stress, and antioxidant agents have demonstrated antiarrhythmic benefit in humans (93). Oxidative stress is frequently discussed in terms of the relative amounts of nitric oxide (NO•) and superoxide anion ( ). The amounts of these two species are often inversely correlated, in part, because of NO• oxidation by

). The amounts of these two species are often inversely correlated, in part, because of NO• oxidation by  to form peroxynitrite and other reactive oxygen species (ROS). NO• and

to form peroxynitrite and other reactive oxygen species (ROS). NO• and  are modulators of vascular and myocardial function. NO• is produced by three nitric oxide synthases including the endothelial isoform, eNOS. This isoform is present in endothelial cells of the vasculature, and NO• produced from this source causes vasodilation, inhibits the development of atherosclerosis, and prevents thrombosis. In the heart, endocardial cells have tremendous similarity to the endothelium and are the main source of NO• under nonpathological conditions (9). Endocardial cells possess eNOS and release NO•, prostacyclin, and endothelin (83). NO• has been shown to enhance diastolic relaxation, modulate cardiac contractility, and affect rhythmicity (87, 91). Vessels in the atrial and ventricular myocardium also have endothelial cells that express eNOS, which may serve as another source of NO• (9). In addition, eNOS is expressed by cardiac myocytes, but at levels that are much lower than that observed in the endocardial cells or endothelium (105). Reduction of NO• in the eNOS knockout mouse leads to increased arrhythmic risk (54).

are modulators of vascular and myocardial function. NO• is produced by three nitric oxide synthases including the endothelial isoform, eNOS. This isoform is present in endothelial cells of the vasculature, and NO• produced from this source causes vasodilation, inhibits the development of atherosclerosis, and prevents thrombosis. In the heart, endocardial cells have tremendous similarity to the endothelium and are the main source of NO• under nonpathological conditions (9). Endocardial cells possess eNOS and release NO•, prostacyclin, and endothelin (83). NO• has been shown to enhance diastolic relaxation, modulate cardiac contractility, and affect rhythmicity (87, 91). Vessels in the atrial and ventricular myocardium also have endothelial cells that express eNOS, which may serve as another source of NO• (9). In addition, eNOS is expressed by cardiac myocytes, but at levels that are much lower than that observed in the endocardial cells or endothelium (105). Reduction of NO• in the eNOS knockout mouse leads to increased arrhythmic risk (54).

is a free radical produced by several enzyme systems and is one of the major biologically relevant oxidizing species determining cellular redox state.

is a free radical produced by several enzyme systems and is one of the major biologically relevant oxidizing species determining cellular redox state.  is dismutated to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) either spontaneously or by any of three superoxide dismutases (SODs). H2O2 is reduced further by catalase or peroxidases. Enzyme systems and organelles known to produce

is dismutated to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) either spontaneously or by any of three superoxide dismutases (SODs). H2O2 is reduced further by catalase or peroxidases. Enzyme systems and organelles known to produce  include xanthine oxidase (XO), uncoupled NOS, mitochondria, and NADPH oxidases. NADPH oxidases consist of multiple subunits, including p47 and p22phox, that must be present for activity and are highly regulated by the renin–angiotensin signaling cascade (38, 117). Recently, NADPH oxidase-mediated production of

include xanthine oxidase (XO), uncoupled NOS, mitochondria, and NADPH oxidases. NADPH oxidases consist of multiple subunits, including p47 and p22phox, that must be present for activity and are highly regulated by the renin–angiotensin signaling cascade (38, 117). Recently, NADPH oxidase-mediated production of  has been noted in AF (28).

has been noted in AF (28).

There is evidence that oxidative stress may contribute to the risk of arrhythmias. Lipid peroxidation, a common byproduct of oxidative stress, has been associated with arrhythmic risk, and this risk can be mitigated by antioxidants, such as statins and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (73, 93). Vitamin E analogues reduce ischemia/reperfusion-induced arrhythmias, and this change is associated with reduced ROS production (108), Another synthetic ROS scavenger, MTDQ-A (6,6-methylene bis 2,2-dimethyl-4-methane sulphonic acid: Na-1,2-dihydroquinoline), reduced the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias following coronary ligation in a dog (99). Carnes et al. have shown that pacing induced AF decreases tissue ascorbate levels and increases protein nitration, a biomarker of oxidative and nitrosative stress (17). In AF, biochemical evidence of oxidation by peroxynitrite and hydroxyl (•OH) radicals, both downstream products of  generation, has been demonstrated (74). In a canine rapid atrial pacing model, vitamin C decreases peroxynitrite formation (a byproduct of NO• oxidation by

generation, has been demonstrated (74). In a canine rapid atrial pacing model, vitamin C decreases peroxynitrite formation (a byproduct of NO• oxidation by  ) and reduces the incidence of postoperative AF in humans (17).

) and reduces the incidence of postoperative AF in humans (17).

In a swine rapid atrial pacing model of AF, we have shown that AF is associated with NADPH oxidase activation, production of  , and reduced NO• bioavailability. As discussed above, antioxidants show promise in reducing AF incidence, so it appears possible that the AF-induced oxidative stress might be involved in the propagation of the arrhythmia. Because the atrial endocardium shares many characteristics with the arterial endothelium, we hypothesized that it may demonstrate alterations in redox active proteins in response to changes in shear stress that could increase atrial oxidative stress during AF. To test this hypothesis, we studied a pig model of AF. A specially designed pacemaker was inserted into the right atrium (RA), and the atrium paced at a rate of 600 bpm to induce AF. The atrioventricular (AV) node was abolished using radiofrequency ablation, and a pacemaker was inserted into the right ventricle (RV) to maintain ventricular rates at 100 bpm. Control pigs had AV nodal ablation and subsequent right-sided AV sequential pacing at 100 bpm, such that the ventricular rate was identical in both sets of animals. After one week, animals were euthanized, and the hearts were removed for study. NO• electrodes were fabricated with coated carbon fibers (13, 14). The electrodes were calibrated with serial dilutions of a saturated, degassed NO• solution. The calibration curve was linear with respect to NO• with a detection limit around 10 nmol/L. NO• concentration was measured under basal conditions and after stimulation with the calcium ionophore, A23187 (1 μmol/L). Interestingly, basal NO• concentration was three-fold higher in the left atrium (LA) than any of the other tissues studied. AF for one week decreased NO• concentration by almost one-fourth (15 ± 6 vs. 56 ± 16 nmol/L, p < 0.01). Also, AF dramatically decreased stimulated LA NO• release (31 ± 12 vs. 107 ± 34 nmol/L for control left atria, p < 0.01). The effects of AF on NO• concentration were comparable in the left atrial appendage (LAA). AF did not cause a significant change in basal or stimulated NO• concentration in the ascending Aorta.

, and reduced NO• bioavailability. As discussed above, antioxidants show promise in reducing AF incidence, so it appears possible that the AF-induced oxidative stress might be involved in the propagation of the arrhythmia. Because the atrial endocardium shares many characteristics with the arterial endothelium, we hypothesized that it may demonstrate alterations in redox active proteins in response to changes in shear stress that could increase atrial oxidative stress during AF. To test this hypothesis, we studied a pig model of AF. A specially designed pacemaker was inserted into the right atrium (RA), and the atrium paced at a rate of 600 bpm to induce AF. The atrioventricular (AV) node was abolished using radiofrequency ablation, and a pacemaker was inserted into the right ventricle (RV) to maintain ventricular rates at 100 bpm. Control pigs had AV nodal ablation and subsequent right-sided AV sequential pacing at 100 bpm, such that the ventricular rate was identical in both sets of animals. After one week, animals were euthanized, and the hearts were removed for study. NO• electrodes were fabricated with coated carbon fibers (13, 14). The electrodes were calibrated with serial dilutions of a saturated, degassed NO• solution. The calibration curve was linear with respect to NO• with a detection limit around 10 nmol/L. NO• concentration was measured under basal conditions and after stimulation with the calcium ionophore, A23187 (1 μmol/L). Interestingly, basal NO• concentration was three-fold higher in the left atrium (LA) than any of the other tissues studied. AF for one week decreased NO• concentration by almost one-fourth (15 ± 6 vs. 56 ± 16 nmol/L, p < 0.01). Also, AF dramatically decreased stimulated LA NO• release (31 ± 12 vs. 107 ± 34 nmol/L for control left atria, p < 0.01). The effects of AF on NO• concentration were comparable in the left atrial appendage (LAA). AF did not cause a significant change in basal or stimulated NO• concentration in the ascending Aorta.

NOS expression from AF and control animals was quantified with Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody against eNOS. NOS protein expression in the LA of the AF group was 46% less than in control animals (p < 0.01). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the majority of NOS activity was endocardial and that differences between the groups were confined to this region. In the RA and ventricles, there were similar trends that did not achieve statistical significance. NOS protein expression was not different in the aorta of control and experimental animals, consistent with the observation that aortic NO• concentrations were similar in the two groups. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in NOS expression between control and AF animals in the LAA, despite the observation that NO• levels were decreased three-fold in the AF group. One possible explanation for the reduction in NO• is increased oxidative degradation by  . We investigated this possibility in the experiments described below.

. We investigated this possibility in the experiments described below.

After a week of AF induced by rapid atrial pacing in pigs,  production from acutely isolated heart tissue was measured by two independent techniques, electron spin resonance (ESR) and SOD-inhibitable cytochrome C reduction assays. Compared to control animals with equivalent ventricular heart rates, basal

production from acutely isolated heart tissue was measured by two independent techniques, electron spin resonance (ESR) and SOD-inhibitable cytochrome C reduction assays. Compared to control animals with equivalent ventricular heart rates, basal  production was increased 2.7-fold (p < 0.01) and 3.0-fold (p < 0.02) in the LA and LAA, respectively. A similar 3.0-fold (p < 0.01) increase in LAA

production was increased 2.7-fold (p < 0.01) and 3.0-fold (p < 0.02) in the LA and LAA, respectively. A similar 3.0-fold (p < 0.01) increase in LAA  production was observed using a cytochrome C reduction assay. The increases could not be explained by changes in atrial total SOD activity.

production was observed using a cytochrome C reduction assay. The increases could not be explained by changes in atrial total SOD activity.

Both ESR and the cytochrome C assay confirmed a similar increase in  production in the LAA. In the LA, there was evidence for increased intracellular but not extracellular

production in the LAA. In the LA, there was evidence for increased intracellular but not extracellular  , however. These results are consistent with our previous observations that oxidative degradation of NO• appears localized predominately to the LAA while decreased bioavailability of LA NO• can be explained by downregulation of eNOS in the LA endocardium (13).

, however. These results are consistent with our previous observations that oxidative degradation of NO• appears localized predominately to the LAA while decreased bioavailability of LA NO• can be explained by downregulation of eNOS in the LA endocardium (13).

The NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin (100 μg/mL), reduced LAA  production by 91%, suggesting a role of the NADPH oxidase. To investigate this further, LAA NADPH oxidase activities were compared directly using membrane preparations from AF and control pigs. There was a 4.4-fold increase in NADPH activity in the LAA of pigs with AF (p = 0.02). The NADPH oxidase activity was 0.4 ± 0.1 in controls compared to 1.8 ± 0.5 nmol

production by 91%, suggesting a role of the NADPH oxidase. To investigate this further, LAA NADPH oxidase activities were compared directly using membrane preparations from AF and control pigs. There was a 4.4-fold increase in NADPH activity in the LAA of pigs with AF (p = 0.02). The NADPH oxidase activity was 0.4 ± 0.1 in controls compared to 1.8 ± 0.5 nmol  /mg tissue*min in AF pigs. The LA showed a similar trend toward increased NADPH oxidase activity (p = 0.06).

/mg tissue*min in AF pigs. The LA showed a similar trend toward increased NADPH oxidase activity (p = 0.06).

Because xanthine oxidase (XO) is another source of  which can be activated concomitantly with the NADPH oxidase (72), we also investigated changes in XO activity caused by AF. Although the overall

which can be activated concomitantly with the NADPH oxidase (72), we also investigated changes in XO activity caused by AF. Although the overall  production attributable to this system was lower than that of the NADPH oxidase, incubation of LAA with oxypurinol reduced

production attributable to this system was lower than that of the NADPH oxidase, incubation of LAA with oxypurinol reduced  production by 85%. Furthermore, LAA XO activity also showed a 4.4-fold increase with AF (p = 0.01), rising from 0.1 ± 0.1 in control to 0.5 ± 0.1 nmol

production by 85%. Furthermore, LAA XO activity also showed a 4.4-fold increase with AF (p = 0.01), rising from 0.1 ± 0.1 in control to 0.5 ± 0.1 nmol  /mg tissue*min in AF pigs. In the case of XO, the differences between activities in the control and AF groups in the LA were also statistically significant (p = 0.04).

/mg tissue*min in AF pigs. In the case of XO, the differences between activities in the control and AF groups in the LA were also statistically significant (p = 0.04).

Western blot analysis of Nox 1, Nox 2 (gp91phox), Nox 4, and p22phox showed no change in relative protein amounts caused by AF, suggesting that activation rather than transcriptional regulation was responsible for the increased activity (42, 53). The small G-protein, Rac1, is essential for assembly of the active NADPH oxidase complex (85, 90). Therefore, we performed experiments to determine if AF was associated with an increase in active GTP-bound Rac1. Rac1 activity assays demonstrated that AF increased active Rac1 in the LAA by 6.9-fold (p < 0.05) as compared to the amount in control pigs.

Other sources of oxidative stress may be important in AF, and the sources may change with time. For example, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is activated by NF-κB and is associated with inflammation and oxidant stress. Increased iNOS is correlated with more 3-nitrotyrosine modification, mediated by peroxynitrite, and with enhanced apoptosis in AF tissue (35, 86). Therefore, iNOS cannot be excluded as another source of oxidative stress and the pathology in AF.

In summary, we demonstrated that AF was associated with regionally correlated decreases in NO• and increases  production. The increased

production. The increased  production was at least in part the result of increased NADPH oxidase and XO activities. Increased NADPH oxidase activity could be explained by an increased in active Rac1, a required cofactor. These observations provide a link between AF and activation of renin-angiotensin system (RAS), since AngII is a potent stimulator of the NADPH oxidase. While the presence of peroxynitrite was not examined directly in these studies, based on the data noted above, peroxynitrite is likely to be elevated since there is evidence of increased atrial nitrotyrosine, the byproduct of peroxynitrite and tyrosine. This idea led to our interest in RAS activation and arrhythmias.

production was at least in part the result of increased NADPH oxidase and XO activities. Increased NADPH oxidase activity could be explained by an increased in active Rac1, a required cofactor. These observations provide a link between AF and activation of renin-angiotensin system (RAS), since AngII is a potent stimulator of the NADPH oxidase. While the presence of peroxynitrite was not examined directly in these studies, based on the data noted above, peroxynitrite is likely to be elevated since there is evidence of increased atrial nitrotyrosine, the byproduct of peroxynitrite and tyrosine. This idea led to our interest in RAS activation and arrhythmias.

In humans, we compared serum markers of oxidation in individuals with or without permanent AF (77). We used derivatives of reactive oxidative metabolites (DROMs) and the ratio of oxidized to reduced glutathione (Eh GSH), and the ratio of oxidized to reduced cysteine (Eh CySH) to quantify oxidative stress. DROMs is a colorimetric assay that detects mostly lipid peroxides. DROMs were measured in Carr units, with higher values indicating increased oxidative stress. The redox states (Eh) of the thiol/disulfide pools were calculated with the Nernst equation: Eh = Eo + RT/nF ln [disulfide]/[thiol]2, where Eo is the standard potential for the redox couple, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, n is 2 for the number of electrons transferred, and F is the Faraday constant. The standard potential Eo used for the glutathione and cysteine redox couples was −264 and −250 mV, respectively. Less negative Eh numbers imply a more oxidized state. The results showed that all measures of oxidative stress were significantly increased in AF patients compared with controls. The AF group showed more oxidation, with a mean Eh GSH of −133 ± 21 mV (±SD) and Eh CySH of −68 ± 6 mV (±SD) compared with the control group, which had a mean Eh GSH of −154 ± 12 mV (±SD) and Eh CySH of −77 ± 6 mV (±SD). DROMs also showed more oxidation in the AF group. The association of oxidative stress markers to AF persisted even after correction for differences in other conditions that predispose to AF. Other oxidative markers also increased in AF include malondialdehyde and nitrotyrosine (61).

NADPH oxidase is a source of oxidative stress and a major upstream modulator of NF-κB activation (18, 50). NADPH oxidase consists of several proteins that are segregated between membrane and cytosol in resting cells, including the membrane-bound cytochrome b558 catalytic unit, composed of Nox and p22phox subunits, and multiple cytoplasmic accessory or signaling subunits (Rac, p47phox, and p67phox). The main NADPH oxidase subunit (Nox) has multiple isoforms, Nox2 (gp91phox) is the dominant isoform expressed in myocardium. During activation, the cytosolic NADPH oxidase components translocate to the membrane, where they associate with Nox, to form the active complex. The NADPH oxidase catalyzes the formation of superoxide anion (O2-). Nox 2 has been shown to be increased in the atrium of patients with AF as compared to controls. In the right atrial appendage (RAA) of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the membrane-bound gp91phox/Nox2 containing NADPH oxidase is a main source of superoxide production from human atrial myocytes (50, 118). These results parallel similar findings in animal models (28, 70). A summary of markers of oxidative stress in AF is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indicators of Oxidative Stress during AF

| Indicator | Direction of change | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Nitrotyrosine | ↑ | heart | 17, 74 |

| Nox2 | ↑ | heart | 50 |

| Eh GSH | ↑ | blood | 77 |

| Eh CySH | ↑ | blood | 77 |

| DROMs | ↑ | blood | 77 |

| Superoxide | ↑ | heart | 20, 50 |

| Nitricoxide | ↓ | heart | 13 |

DROMS, derivatives of reactive oxidative metabolites; Eh CySH, ratios of oxidized to reduced cysteine; Eh GSH, ratio of oxidized to reduced glutathione; Nox2, NADPH oxidase type 2.

Gene expression profiling on heart tissue from AF patients also suggests that oxidative stress related genes are regulated in AF (49). Comparing human atrial tissue are collected from patients with permanent AF and from 26 control subjects indicated that the expression of oxidative related genes were significant upregulated and antioxidant genes were downregulated in AF patients. Pro-oxidant genes increased, including monoamine oxidase B, flavin-containing monooxygenase 1, the NADPH oxidase, cytochrome P450, and xanthine oxidase. Antioxidant genes downregulated included glutathione peroxidase 1, glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase (p < 0.01).

NF-κB Activation and the Identified Signaling Pathways Involved in AF

Waved3 (Wa3) mice have a spontaneous mutation of the NF-κB interacting protein 1 (Nkip1), which is a putative repressor of NF-κB (41). The loss of Nkip1 would be expected to result in an inappropriate activation of NF-κB, thus identifying NF-κB-dependent cardiac transcripts. The most striking aspect of the Wa3 phenotype is a profound cardiomyopathy. Myofiber degeneration, necrosis, and mineralization first appear on the anterior aspect of the right ventricle near the outflow tract and extend into the anterior aspect of the adjacent septum. Lesions are evident at birth and became progressively larger with age. By day 14, right ventricle dilation is present (41). This mutation strongly suggests that proper NF-κB regulation is vital to the maintenance of appropriate cardiac function and suggests that dysregulation leads to myopathy.

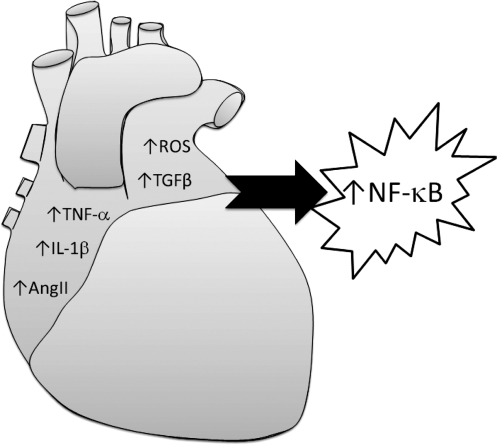

NF-κB is a highly inducible nuclear transcriptional factor and responses to a variety of stimuli (40). The signal pathways involved in NF-κB activation have been widely investigated. Reports focus on activated NF-κB mediated by hypertrophy (113), oxidative stress (6), TNF-α (78, 88), IL-1β (78, 88), TGF-β (34, 76), and the RAS (7, 98). Interestingly, TNF-α (94), IL-1β (109), TGF-β1 (84, 106), and RAS (100, 102) are also reported to be involved in the AF electrical and structural remodeling.

The system RAS is a key signaling pathway in the cardiovascular system (29, 81). Activation of this system is associated with increased cardiovascular death (69). A critical component of this system is angiotensin converting system (ACE), which cleaves the angiotensin I to AngII. In humans, increased AngII levels are associated with an increased arrhythmic risk (1), and the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (32, 67) have decreased this arrhythmic risk. Additionally, patients with AF are known to have increased levels of ACE and AngII receptors (5, 36). ACE inhibition has been shown to reduce the incidence of AF in a number of different settings including after myocardial infarction and in the setting of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (3, 107). ACE inhibitor therapy has been shown to be a negative predictor of AF after coronary artery bypass grafting, while postoperative withdrawal of ACE inhibitors has been associated with the development of AF (71).

Cardiac-restricted ACE or angiotensin receptor overexpression results in conduction abnormalities and sudden death (47, 112). Cardiac-restricted expression of ACE2, an enzyme that produces a shortened form of angiotensin whose role is unclear, causes a high incidence of sudden death, severe conduction disturbances, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and terminal ventricular fibrillation (27).

Additionally, TNF-α expression is increased in patients with AF (109). Comparing RAA samples of patients with and without AF showed that a significant increase in the fibrosis of the RAA and TNF-α protein expression in the patients with AF. Similar results have been reported for plasma TNF-α, which is significantly increased before and after pharmacological cardioversion in patients with paroxysmal AF as compared to sinus rhythm controls (92). TNF-α cardiac-restricted overexpression mice have structural remodeling and conduction system disease conducive to arrhythmias (94). Electrical alterations include AV conduction abnormalities, supraventricular arrhythmias, and shortened AV interval with a wide QRS duration. A downregulation of connexin40 was noted and may help explain the findings.

NF-κB activation has been reported to be involved in the TNF-α-mediated signaling pathway (78, 88). This NF-κB activation is mediated through ROS-dependent PKAc pathway (44). With 20 min of TNF-α stimulation, ROS increased by ∼2-fold. The induced ROS activated NF-κB through NF-κB/RelA Ser phosphorylation, a critical modification for its transcriptional activity. TNF-α-mediated NF-κB activation could be blocked by antioxidant treatment, PKAc inhibitors, and siRNA-mediated PKAc knockdown.

Activation of the IL-1β pathway results in NF-κB inhibitor (IκB) phosphorylation and subsequent cytoplasm-nucleic NF-κB translocation (89). IL-1β alters transcriptional regulation of NF-κB and NF-κB-dependent mRNA (89). IL-1β has been implicated in arrhythmic risk during cardiac cellular myoplasty. In a rat infarction model, skeletal myoblast injection induced a high level of IL-1β for at least 1 week compared to bone marrow-derived progenitor cell injection. Moreover, the skeletal myoblast group displayed a higher occurrence of ventricular premature contractions and was more susceptible to isoproterenol-induced ventricular tachycardia compared to the bone marrow progenitor and saline injected control groups (22). IL-1 receptor knockout mice have decreased inflammation and fibrosis after infarction, suggesting that IL-1β contributes to the substrates for arrhythmia (10).

In osteoclasts, TGF-β1 activates two downstream signaling pathways to regulate transcription (34). One pathway is mediated by NF-κB activation, while the other one is mediated by cytoplasm-nucleic transport protein Smad2. Comparing the RAA of 11 patients with chronic AF and underlying valvular heart disease and seven patients in sinus rhythm with VHD to 11 patients in the sinus-rhythm control group showed significant upregulation of the key molecules in the TGF-β1-Smad pathway in AF patient samples when compared to control group (84). Consistent with a causal relationship, cardiac restricted TGF-β overexpression results in atrial fibrosis and an increased risk of AF (106).

In summary, TNF-α, IL-1β, TGF-β, and AngII-mediated pathways have been implicated in arrhythmias and are associated with NF-κB activation (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Summary of identified signaling pathways involved in AF that may lead to NF-κB activation in atrial fibrillation (AF).

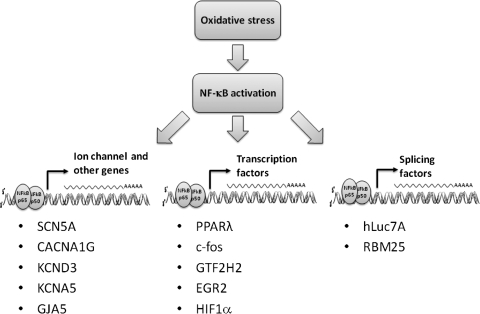

NF-κB-Dependent Transcriptional Regulation in AF

NF-κB is required for normal cell growth and survival. NF-κB deficiency is lethal. Inducible expression of a mutated inhibitor of NFκB has allowed for a profile of the NF-κB dependent gene regulation network (7). Nevertheless, this network is likely to be cell type specific (7, 39), and knowledge of the role of NF-κB in cardiac cells is limited. While understanding the role of NF-κB in AF is in its early stages, we can speculate about several possible mechanisms whereby NF-κB could be involved. Activated NF-κB can have direct effects on ion channel promoter regions, alter other transcription factor expression levels, or influence mRNA splicing (Fig. 4). The canonical consensus binding site sequences for NF-κB are 5′-GGGGATYCC-3′ for p50 and 5′-GGGRNTTTCC-3′ for p65, where Y is a pyrimidine, R is a purine, and N is any nucleotide (115). Classically, NF-κB binds these sites as a heterodimer of one p50 and one p65 subunits. Binding of a single subunit is thought to be insufficient to influence transcriptional activity (55). By promoter sequencing analysis, we found that the cardiac sodium channel SCN5A promoter region contained a NF-κB binding sequence. This suggests that SCN5A may be one of the candidate genes under NF-κB regulation. An appropriate number and function of Na+ channels is critical for normal cardiac electrical activity (96). Either excess or reduced channel current results in increased arrhythmic risk, as happens in the inherited sudden death syndromes Long QT syndrome type 3 (68) and Brugada syndrome (63), respectively. As discussed above, downregulation of the cardiac sodium channel is seen in many models of AF (95, 97) and AF is associated with increased RAS activation (100, 102) and oxidative stress (49).

FIG. 4.

Three mechanisms by which oxidative stress and NF-κB activation may lead contribute to atrial fibrillation (AF). NF-κB can have direct effects on ion channel promoter regions, may alter other transcription factor expression levels, or may influence mRNA splicing.

It is well established that one effect of increased RAS activation is AngII-dependent stimulation of the enzyme NADPH oxidase (43, 75). We showed that AngII exposure resulted in a transcriptional downregulation of Na+ channels (98). This downregulation required the NADPH oxidase and was mediated by H2O2. AngII or H2O2 treatment of cardiomyocytes resulted in increased NF-κB binding to the cardiac Na+ channel promoter with subsequent reduction in transcriptional activity. This response to NF-κB activation and binding is somewhat unusual, compared to the more common activation of transcription with NF-κB binding. Nevertheless, simultaneous overexpression of p50 and p65 could recapitulate the effect of AngII or oxidative stress, and mutation of the NF-κB consensus sequence prevented the downregulation of transcription. While these experiments were performed with mouse cells and the mouse Na+ channel promoter, the human Na+ channel promoter also has an homologous NF-κB binding site (GenBank accession numbers AY313163 for human and AY769981 for mouse).

In summary, we found that AngII could downregulated cardiac Na+ channels by an NF-κB-dependent mechanism. This may help explain the efficacy of RAS inhibitors to prevent AF (24, 26). The reduction in sodium current seen with AngII is similar to its effect on other cardiac ion channels, including the transient outward current α-subunit Kv4.3 (60), the gap junction protein connexin 43 (47), connexin 40 (31, 47), and the calcium current (31), which may be mediated by comparable mechanisms and also may contribute to enhanced arrhythmic risk in states of increased oxidative stress.

Inspecting the promoter regions of other channels and subunits altered during AF revealed that the T-type Ca2+ channel (CACNA1G), the transient outward current (KCND3), the ultra-rapid delayed rectifier (KCNA5), and connexin 40 (GJA5) have NF-κB consensus binding sequences. All appear to undergo transcriptional regulation during AF, but only SCN5A has direct evidence supporting its regulation by NF-κB. If it should come to pass that these channels are regulated in a similar way to SCN5A, then a substantial component of electrical remodeling in AF may be prevented by altering NF-κB signaling.

Aside from the direct effect of NF-κB on ion channel promoters, it is possible that this transcription factor may play a role in alternative splicing of ion channels that promotes arrhythmic risk. Several cardiac ion channels are alternatively spliced, including the cardiac Na+ channel (97). Human heart failure, a condition linked with increased risk of AF, is associated with increased prevalence of three splice variants of the SCN5A gene that encode for truncated, nonfunctional channels (GenBank accession numbers: EF092292, EF092293, and EF092294, respectively). These alternatively spliced mRNA variants are likely to reduce Na+ current to levels that might contribute to arrhythmic risk alone or in combination with other inciting causes. Gene array comparisons of splicing factor expression between normal and heart failure tissue has demonstrated changes in hypoxia-inducing factor-1α (HIF1α). HIF1α is a key transcriptional regulatory molecule elevated in hypoxia and inflammation. The HIF1α promoter contains an NF-κB binding element, and NF-κB is an upstream regulator during HIF1α activation (45). Among other things, HIF1α regulates mRNA splicing factors, such as hLuc7A and RBM25 (119). Sequence analysis shows that there is a RBM25 binding site in the SCN5A region where abnormal mRNA splicing occurs, suggesting NF-κB may be upstream of the alternative splicing of this channel during cardiac oxidative stress, inflammation, or hypoxia.

In addition to affecting transcription and splicing, NF-κB regulation during AF could conceivably indirectly affect AF-related genes by affecting the transcription factors that regulate them. To date, there is limited knowledge of transcription factor alterations during AF. PPARs and c-fos are known to be regulated in AF (49) and are involved in redox signal pathways (19, 33). Two other transcription factors, general transcription factor IIH polypeptide 2 (GTF2H2) and early growth response 2 (EGR2), are increased in AF (49) and have NF-κB consensus sequences in their promoters, raising the possibility that NF-κB may be involved in their upregulation during AF.

Conclusions

While it is likely that multiple mechanisms contribute to AF risk, inflammation and oxidative stress seem to play large roles (Fig. 5). As a central response element of these two inciting causes, NF-κB is likely to be mediating some of the changes that either precipitate or perpetuate AF. Recent data have begun to show how NF-κB might be involved in altering ion channel transcription in ways that would contribute to arrhythmic risk. Therefore, the NF-κB signaling cascade may represent a reasonable target for future antiarrhythmic drug development.

FIG. 5.

A proposed scheme of how NF-κB may be involved in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation (AF). AF is known to be associated with systemic and cardiac oxidative stress. Oxidative stress can activate NF-κB. NF-κB has been shown to downregulate cardiac Na+ channels and may have other proarrhythmic effects, perpetuating AF.

Abbreviations Used

- ACE

angiotensin emuerting enzyme

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AngII

angiotensin II

- AV

atrioventricular node

- CARP

cardiac ankyrin repeat protein

- DROM

derivative of reactive oxidative metabolites

- EGR2

early growth response

- Eh

oxidized to reduced thiol redox states

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- FHL1

four and a half LIM domains protein-1

- FOS/v-fos

FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- GTF2H2

general transcription factor IIH polypeptide 2

- hERG

human Ether-a-go-go related gene

- HIF1α

hypoxia inducing factor-1α

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KCNJ2

potassium channel

- LA

left atrium

- LAA

left atrial appendage

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NO•

nitric oxide

superoxide anion

- PPAPγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- RA

right atrium

- RAS

renin–angiotensin system

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RV

right ventricle

- SCN5A

sodium channel

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- XO

xanthine oxidase

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL085520, R01 HL085558, R01 HL073753, an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 0440164N, and a Veterans Affairs MERIT grant.

References

- 1.Akar FG. Spragg DD. Tunin RS. Kass DA. Tomaselli GF. Mechanisms underlying conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95:717–725. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144125.61927.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allessie M. Ausma J. Schotten U. Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:230–246. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsheikh–Ali AA. Wang PJ. Rand W. Konstam MA. Homoud MK. Link MS. Estes NA., III Salem DN. Al Ahmad AM. Enalapril treatment and hospitalization with atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Am Heart J. 2004;147:1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blitzer M. Costeas C. Kassotis J. Reiffel JA. Rhythm management in atrial fibrillation–with a primary emphasis on pharmacological therapy: Part 1. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:590–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boldt A. Wetzel U. Weigl J. Garbade J. Lauschke J. Hindricks G. Kottkamp H. Gummert JF. Dhein S. Expression of angiotensin II receptors in human left and right atrial tissue in atrial fibrillation with and without underlying mitral valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1785–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowie A. O'Neill LA. Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasier AR. The NF-κB regulatory network. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2006;6:111–130. doi: 10.1385/ct:6:2:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brundel BJ. Henning RH. Kampinga HH. van Gelder IC. Crijns HJ. Molecular mechanisms of remodeling in human atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:315–324. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brutsaert DL. Cardiac endothelial–myocardial signaling: Its role in cardiac growth, contractile performance, and rhythmicity. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:59–115. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bujak M. Dobaczewski M. Chatila K. Mendoza LH. Li N. Reddy A. Frangogiannis NG. Interleukin-1 receptor type I signaling critically regulates infarct healing and cardiac remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:57–67. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunch TJ. Mahapatra S. Bruce GK. Johnson SB. Miller DV. Horne BD. Wang XL. Lee HC. Caplice NM. Packer DL. Impact of transforming growth factor-β1 on atrioventricular node conduction modification by injected autologous fibroblasts in the canine heart. Circulation. 2006;113:2485–2494. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.570796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein B. Nattel S. Atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai H. Li Z. Dikalov S. Holland SM. Hwang J. Jo H. Dudley SC., Jr. Harrison DG. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived hydrogen peroxide mediates endothelial nitric oxide production in response to angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48311–48317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai H. Li Z. Goette A. Mera F. Honeycutt C. Feterik K. Wilcox JN. Dudley SC., Jr. Harrison DG. Langberg JJ. Downregulation of endocardial nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in atrial fibrillation: potential mechanisms for atrial thrombosis and stroke. Circulation. 2002;106:2854–2858. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039327.11661.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell KP. Lipshutz GM. Denney GH. Direct photoaffinity labeling of the high affinity nitrendipine-binding site in subcellular membrane fractions isolated from canine myocardium. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5384–5387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao K. Xia X. Shan Q. Chen Z. Chen X. Huang Y. Changes of sarcoplamic reticular Ca2+-ATPase and IP3-I receptor mRNA expression in patients with atrial fibrillation. Chin Med J. 2002;115:664–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carnes CA. Chung MK. Nakayama T. Nakayama H. Baliga RS. Piao S. Kanderian A. Pavia S. Hamlin RL. McCarthy PM. Bauer JA. Van Wagoner DR. Ascorbate attenuates atrial pacing-induced peroxynitrite formation and electrical remodeling and decreases the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2001;89:E32–E38. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.097644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cave AC. Brewer AC. Narayanapanicker A. Ray R. Grieve DJ. Walker S. Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:691–728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charital YM. Haasteren GV. Massiha A. Schlegel W. Fujita T. A functional NF-κB enhancer element in the first intron contributes to the control of c-fos transcription. Gene. 2009;430:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CL. Lin JL. Lai LP. Pan CH. Huang SK. Lin CS. Altered expression of FHL1, CARP, TSC-22 and P311 provide insights into complex transcriptional regulation in pacing-induced atrial fibrillation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christ T. Boknik P. Wohrl S. Wettwer E. Graf EM. Bosch RF. Knaut M. Schmitz W. Ravens U. Dobrev D. L-type Ca2+ current downregulation in chronic human atrial fibrillation is associated with increased activity of protein phosphatases. Circulation. 2004;110:2651–2657. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145659.80212.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman TA. Kunsch C. Maher M. Ruben SM. Rosen CA. Acquisition of NFκB1-selective DNA binding by substitution of four amino acid residues from NFkB1 into RelA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3850–3859. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.d'Avila A. Ruskin JN. Nonpharmacologic strategies: The evolving story of ablation and hybrid therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:20H–24H. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai SM. Zhang S. Chu JM. Guo YH. Chen KP. Yao S. Blockade of renin-angiotensin system: Aa supplementary treatment for circumferential pulmonary vein isolation in treating persistent atrial fibrillation. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:767–772. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danik S. Neuzil P. d'Avila A. Malchano ZJ. Kralovec S. Ruskin JN. Reddy VY. Evaluation of catheter ablation of periatrial ganglionic plexi in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dilaveris P. Giannopoulos G. Synetos A. Stefanadis C. The role of renin angiotensin system blockade in the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Hematol Disord. 2005;5:387–403. doi: 10.2174/156800605774370317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donoghue M. Wakimoto H. Maguire CT. Acton S. Hales P. Stagliano N. Fairchild–Huntress V. Xu J. Lorenz JN. Kadambi V. Berul CI. Breitbart RE. Heart block, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden death in ACE2 transgenic mice with downregulated connexins. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudley SC., Jr. Hoch NE. McCann LA. Honeycutt C. Diamandopoulos L. Fukai T. Harrison DG. Dikalov SI. Langberg J. Atrial fibrillation increases production of superoxide by the left atrium and left atrial appendage: role of the NADPH and xanthine oxidases. Circulation. 2005;112:1266–1273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dzau VJ. Tissue renin-angiotensin system in myocardial hypertrophy and failure. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:937–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao G. Shang LL. Zhou A. Jiao Z. Gaconnet G. Dudley SC., Jr. The possible mechanism of acquired sodium channel mRNA splicing variants with human heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118:S873. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gassanov N. Brandt MC. Michels G. Lindner M. Er F. Hoppe UC. Angiotensin II-induced changes of calcium sparks and ionic currents in human atrial myocytes: Potential role for early remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Cell Calcium. 2006;39:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavras I. Gavras H. The antiarrhythmic potential of angiotensin II antagonism: experience with losartan. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:512–517. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genolet R. Wahli W. Michalik L. PPARs as drug targets to modulate inflammatory responses? Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3:361–375. doi: 10.2174/1568010042634578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gingery A. Bradley EW. Pederson L. Ruan M. Horwood NJ. Oursler MJ. TGF-β coordinately activates TAK1/MEK/AKT/NFκB and SMAD pathways to promote osteoclast survival. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2725–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goette A. Bukowska A. Lendeckel U. Erxleben M. Hammwohner M. Strugala D. Pfeiffenberger J. Rohl FW. Huth C. Ebert MP. Klein HU. Rocken C. Angiotensin II receptor blockade reduces tachycardia-induced atrial adhesion molecule expression. Circulation. 2008;117:732–742. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goette A. Staack T. Rocken C. Arndt M. Geller JC. Huth C. Ansorge S. Klein HU. Lendeckel U. Increased expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and angiotensin-converting enzyme in human atria during atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1669–1677. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grammer JB. Bosch RF. Kuhlkamp V. Seipel L. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for “remodeling” of the L-type Ca2+ channel in persistent atrial fibrillation in humans. Z Kardiol. 2000;89 Suppl 4:IV23–IV29. doi: 10.1007/s003920070060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griendling KK. Sorescu D. Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: Role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:494–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grove M. Plumb M. C/EBP, NF-κB, and c-Ets family members and transcriptional regulation of the cell-specific and inducible macrophage inflammatory protein 1a immediate-early gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5276–5289. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall G. Hasday JD. Rogers TB. Regulating the regulator: NF-κB signaling in heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herron BJ. Rao C. Liu S. Laprade L. Richardson JA. Olivieri E. Semsarian C. Millar SE. Stubbs L. Beier DR. A mutation in NFκB interacting protein 1 results in cardiomyopathy and abnormal skin development in wa3 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:667–677. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heymes C. Bendall JK. Ratajczak P. Cave AC. Samuel JL. Hasenfuss G. Shah AM. Increased myocardial NADPH oxidase activity in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:2164–2171. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iglarz M. Touyz RM. Viel EC. Amiri F. Schiffrin EL. Involvement of oxidative stress in the profibrotic action of aldosterone. Interaction wtih the renin-angiotension system. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jamaluddin M. Wang S. Boldogh I. Tian B. Brasier AR. TNF-α-induced NF-κB/RelA Ser(276) phosphorylation and enhanceosome formation is mediated by an ROS-dependent PKAc pathway. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1419–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung YJ. Isaacs JS. Lee S. Trepel J. Neckers L. IL-1beta-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1α via an NFκB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 2003;17:2115–2117. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0329fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung YJ. Isaacs JS. Lee S. Trepel J. Neckers L. Microtubule disruption utilizes an NFκ B-dependent pathway to stabilize HIF-1α protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7445–7452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasi VS. Xiao HD. Shang LL. Iravanian S. Langberg J. Witham EA. Jiao Z. Gallego CJ. Bernstein KE. Dudley SC., Jr. Cardiac-restricted angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression causes conduction defects and connexin dysregulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H182–H192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00684.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kharche S. Garratt CJ. Boyett MR. Inada S. Holden AV. Hancox JC. Zhang H. Atrial proarrhythmia due to increased inward rectifier current (IK1) arising from KCNJ2 mutation. A simulation study. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim YH. Lim DS. Lee JH. Shim WJ. Ro YM. Park GH. Becker KG. Cho–Chung YS. Kim MK. Gene expression profiling of oxidative stress on atrial fibrillation in humans. Exp Mol Med. 2003;35:336–349. doi: 10.1038/emm.2003.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YM. Guzik TJ. Zhang YH. Zhang MH. Kattach H. Ratnatunga C. Pillai R. Channon KM. Casadei B. A myocardial Nox2 containing NAD(P)H oxidase contributes to oxidative stress in human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2005;97:629–636. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000183735.09871.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleber AG. Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–488. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korantzopoulos P. Kolettis TM. Galaris D. Goudevenos JA. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krijnen PA. Meischl C. Hack CE. Meijer CJ. Visser CA. Roos D. Niessen HW. Increased Nox2 expression in human cardiomyocytes after acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:194–199. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubota I. Han X. Opel DJ. Zhao YY. Baliga R. Huang P. Fishman MC. Shannon RP. Michel T. Kelly RA. Increased susceptibility to development of triggered activity in myocytes from mice with targeted disruption of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1239–1248. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunsch C. Ruben SM. Rosen CA. Selection of optimal κB/Rel DNA-binding motifs: interaction of both subunits of NF-κB with DNA is required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4412–4421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai LP. Su MJ. Lin JL. Lin FY. Tsai CH. Chen YS. Huang SK. Tseng YZ. Lien WP. Down-regulation of L-type calcium channel and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase mRNA in human atrial fibrillation without significant change in the mRNA of ryanodine receptor, calsequestrin and phospholamban: an insight into the mechanism of atrial electrical remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lai LP. Su MJ. Lin JL. Lin FY. Tsai CH. Chen YS. Tseng YZ. Lien WP. Huang SK. Changes in the mRNA levels of delayed rectifier potassium channels in human atrial fibrillation. Cardiology. 1999;92:248–255. doi: 10.1159/000006982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lakshminarayan K. Anderson DC. Herzog CA. Qureshi AI. Clinical epidemiology of atrial fibrillation and related cerebrovascular events in the United States. Neurologist. 2008;14:143–150. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31815cffae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamirault G. Gaborit N. Le MN. Chevalier C. Lande G. Demolombe S. Escande D. Nattel S. Leger JJ. Steenman M. Gene expression profile associated with chronic atrial fibrillation and underlying valvular heart disease in man. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lebeche D. Kaprielian R. Hajjar R. Modulation of action potential duration on myocyte hypertrophic pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leftheriotis DI. Fountoulaki KT. Flevari PG. Parissis JT. Panou FK. Andreadou IT. Venetsanou KS. Iliodromitis EK. Kremastinos DT. The predictive value of inflammatory and oxidative markers following the successful cardioversion of persistent lone atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.012. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leibovitch ER. Hypertension 2008, refining our treatment. Geriatrics. 2008;63:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Letsas KP. Sideris A. Efremidis M. Pappas LK. Gavrielatos G. Filippatos GS. Kardaras F. Prevalence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in Brugada syndrome: A case series and a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2007;8:803–806. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3280112b21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li S. Li X. Zheng H. Xie B. Bidasee KR. Rozanski GJ. Pro-oxidant effect of transforming growth factor-β1 mediates contractile dysfunction in rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:107–117. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li X. Ma C. Dong J. Liu X. Long D. Tian Y. Yu R. The fibrosis and atrial fibrillation: Is the transforming growth factor-β1 a candidate etiology of atrial fibrillation. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70:317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin CS. Pan CH. Regulatory mechanisms of atrial fibrotic remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1489–1508. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lindholm LH. Dahlof B. Edelman JM. Ibsen H. Borch–Johnsen K. Olsen MH. Snapinn S. Wachtell K. Effect of losartan on sudden cardiac death in people with diabetes: Data from the LIFE study. Lancet. 2003;362:619–620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu H. Clancy C. Cormier J. Kass R. Mutations in cardiac sodium channels: Clinical implications. Am J Pharmacogenom. 2003;3:173–179. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200303030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lonn EM. Yusuf S. Jha P. Montague TJ. Teo KK. Benedict CR. Pitt B. Emerging role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiac and vascular protection. Circulation. 1994;90:2056–2069. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Looi YH. Grieve DJ. Siva A. Walker SJ. Anilkumar N. Cave AC. Marber M. Monaghan MJ. Shah AM. Involvement of Nox2 NADPH oxidase in adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2008;51:319–325. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mathew JP. Fontes ML. Tudor IC. Ramsay J. Duke P. Mazer CD. Barash PG. Hsu PH. Mangano DT. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2004;291:1720–1729. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McNally JS. Davis ME. Giddens DP. Saha A. Hwang J. Dikalov S. Jo H. Harrison DG. Role of xanthine oxidoreductase and NAD(P)H oxidase in endothelial superoxide production in response to oscillatory shear stress. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:H2290–H2297. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meerson FZ. Belkina LM. Sazontova TG. Saltykova VA. Arkhipenko Y. The role of lipid peroxidation in pathogenesis of arrhythmias and prevention of cardiac fibrillation with antioxidants. Basic Res Cardiol. 1987;82:123–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01907060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mihm MJ. Yu F. Carnes CA. Reiser PJ. McCarthy PM. Van Wagoner DR. Bauer JA. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:174–180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Munzel T. Hink U. Heitzer T. Meinertz T. Role for NADPH/NADH oxidase in the modulation of vascular tone. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;874:386–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neil JR. Schiemann WP. Altered TAB1:I κB kinase interaction promotes transforming growth factor beta-mediated nuclear factor-κB activation during breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1462–1470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neuman RB. Bloom HL. Shukrullah I. Darrow LA. Kleinbaum D. Jones DP. Dudley SC., Jr. Oxidative stress markers are associated with persistent atrial fibrillation. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1652–1657. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.083923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nunez C. Cansino JR. Bethencourt F. Perez–Utrilla M. Fraile B. Martinez–Onsurbe P. Olmedilla G. Paniagua R. Royuela M. TNF/IL-1/NIK/NF-κB transduction pathway: A comparative study in normal and pathological human prostate (benign hyperplasia and carcinoma) Histopathology. 2008;53:166–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohara K. Miyauchi Y. Ohara T. Fishbein MC. Zhou S. Lee MH. Mandel WJ. Chen PS. Karagueuzian HS. Downregulation of immunodetectable atrial connexin40 in a canine model of chronic left ventricular myocardial infarction: implications to atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2002;7:89–94. doi: 10.1177/107424840200700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ohki R. Yamamoto K. Ueno S. Mano H. Misawa Y. Fuse K. Ikeda U. Shimada K. Gene expression profiling of human atrial myocardium with atrial fibrillation by DNA microarray analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pagliaro P. Penna C. Rethinking the renin-angiotensin system and its role in cardiovascular regulation. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-6900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pan CH. Lin JL. Lai LP. Chen CL. Stephen Huang SK. Lin CS. Downregulation of angiotensin converting enzyme II is associated with pacing-induced sustained atrial fibrillation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pinsky DJ. Patton S. Mesaros S. Brovkovych V. Kubaszewski E. Grunfeld S. Malinski T. Mechanical transduction of nitric oxide synthesis in the beating heart. Circ Res. 1997;81:372–379. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polyakova V. Miyagawa S. Szalay Z. Risteli J. Kostin S. Atrial extracellular matrix remodelling in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:189–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Price MO. Atkinson SJ. Knaus UG. Dinauer MC. Rac activation induces NADPH oxidase activity in transgenic COSphox cells, and the level of superoxide production is exchange factor-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19220–19228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Purcell NH. Tang G. Yu C. Mercurio F. DiDonato JA. Lin A. Activation of NF-κ B is required for hypertrophic growth of primary rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6668–6673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111155798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Qi X. Li K. Rouleau JL. Endocardial endothelium and myocardial performance in rats: Effects of changing extracellular calcium and phenylephrine. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:859–869. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Royuela M. Rodriguez–Berriguete G. Fraile B. Paniagua R. TNF-α/IL-1/NF-κB transduction pathway in human cancer prostate. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:1279–1290. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saas J. Haag J. Rueger D. Chubinskaya S. Sohler F. Zimmer R. Bartnik E. Aigner T. IL-1β, but not BMP-7 leads to a dramatic change in the gene expression pattern of human adult articular chondrocytes-portraying the gene expression pattern in two donors. Cytokine. 2006;36:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sarfstein R. Gorzalczany Y. Mizrahi A. Berdichevsky Y. Molshanski-Mor S. Weinbaum C. Hirshberg M. Dagher MC. Pick E. Dual role of Rac in the assembly of NADPH oxidase, tethering to the membrane and activation of p67phox: A study based on mutagenesis of p67phox-Rac1 chimeras. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16007–16016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarkar D. Vallance P. Harding SE. Nitric oxide: Not just a negative inotrope. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sata N. Hamada N. Horinouchi T. Amitani S. Yamashita T. Moriyama Y. Miyahara K. C-reactive protein and atrial fibrillation. Is inflammation a consequence or a cause of atrial fibrillation? Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:441–445. doi: 10.1536/jhj.45.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Savelieva I. Camm J. Statins and polyunsaturated fatty acids for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:30–41. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sawaya SE. Rajawat YS. Rami TG. Szalai G. Price RL. Sivasubramanian N. Mann DL. Khoury DS. Downregulation of connexin40 and increased prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in transgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1561–H1567. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shang LL. Dudley SC., Jr. Tandem promoters and developmentally regulated 5'- and 3'-mRNA untranslated regions of the mouse Scn5a cardiac sodium channel. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:933–940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shang LL. Gao G. Dudley SC., Jr. The tail of the cardiac sodium channel. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:161–162. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.3.6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shang LL. Pfahnl AE. Sanyal S. Jiao Z. Allen J. Banach K. Fahrenbach J. Weiss D. Taylor WR. Zafari AM. Dudley SC., Jr. Human heart failure is associated with abnormal C-terminal splicing variants in the cardiac sodium channel. Circ Res. 2007;101:1146–1154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shang LL. Sanyal S. Pfahnl AE. Jiao Z. Allen J. Liu H. Dudley SC., Jr. NF-κB-dependent transcriptional regulation of the cardiac scn5a sodium channel by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C372–C379. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00186.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Torok B. Roth E. Mezey B. Temes G. Toth K. Pollak Z. Promising reduction of ventricular fibrillation in experimentally induced heart infarction by antioxidant therapy. Basis Res Cardiol 82 Suppl. 1987;2:347–353. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11289-2_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsai CT. Lai LP. Hwang JJ. Chen WP. Chiang FT. Hsu KL. Tseng CD. Tseng YZ. Lin JL. Renin-angiotensin system component expression in the HL-1 atrial cell line and in a pig model of atrial fibrillation. J Hypertens. 2008;26:570–582. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f34a4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tsai CT. Lai LP. Hwang JJ. Lin JL. Chiang FT. Molecular genetics of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsai CT. Lai LP. Lin JL. Chiang FT. Hwang JJ. Ritchie MD. Moore JH. Hsu KL. Tseng CD. Liau CS. Tseng YZ. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109:1640–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124487.36586.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.van der Velden HMW. van der Zee L. Wijffels MC. van LC. Dorland R. Vos MA. Jongsma HJ. Allessie MA. Atrial fibrillation in the goat induces changes in monophasic action potential and mRNA expression of ion channels involved in repolarization. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:1262–1269. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2000.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vaquero M. Calvo D. Jalife J. Cardiac fibrillation: from ion channels to rotors in the human heart. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vejlstrup NG. Bouloumie A. Boesgaard S. Andersen CB. Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Mortensen SA. Kent JD. Harrison DG. Busse R. Aldershvile J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the human heart: Expression and localization in congestive heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1215–1223. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Verheule S. Sato T. Everett T. Engle SK. Otten D. Rubart–von der LM. Nakajima HO. Nakajima H. Field LJ. Olgin JE. Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-β1. Circ Res. 2004;94:1458–1465. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129579.59664.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vermes E. Tardif JC. Bourassa MG. Racine N. Levesque S. White M. Guerra PG. Ducharme A. Enalapril decreases the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: Insight from the Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trials. Circulation. 2003;107:2926–2931. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072793.81076.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Walker MK. Vergely C. Lecour S. Abadie C. Maupoil V. Rochette L. Vitamin E analogues reduce the incidence of ventricular fibrillations and scavenge free radicals. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1998;12:164–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1998.tb00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang CH. Hu DY. Tang CZ. Wu MY. Mei YQ. Zhao JG. Qi HW. [Changes of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α of right atrial appendages in patients with rheumatic valvular disease complicated with chronic atrial fibrillation] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2005;33:522–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wellens HJ. Twenty-five years of insights into the mechanisms of supraventricular arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1020–1025. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]