Abstract

Sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (thia-PAHs or thiaarenes) are common constituents of air pollution and cigarette smoke, but only a few have been studied for health effects. We evaluated the mutagenicity in Salmonella TA98, TA100, and TA104 of two sulfur-containing derivatives of benzo[c]phenanthrene, phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene (P[3,4-b]T), and phenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene (P[4,3-b]T) as well as their dihydrodiol and sulfone derivatives. In addition, we assessed levels of stable DNA adducts (by 32P-postlabeling) as well as abasic sites (by an aldehydic-site assay) produced by six of these compounds in TA100. P[3,4-b]T and its 6,7- and 8,9-diols, P[3,4-b]T sulfone, P[4,3-b]T, and its 8,9-diol were mutagenic in TA100. P[3,4-b]T sulfone, the most potent mutagen, was approximately twice as potent as benzo[a]pyrene in both TA98 and TA100. Benzo-ring dihydrodiols were much more potent than K-region dihydrodiols, which had little or no mutagenic activity in any strain. P[3,4-b]T sulfone produced abasic sites and not stable DNA adducts; the other five compounds examined, B[c]P, B[c]P 3,4-diol, P[3,4-b]T, P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol, and P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol, produced only stable DNA adducts. P[3,4-b]T sulfone was the only compound that produced significant levels of frameshift mutagenicity and induced mutations primarily at GC sites. In contrast, B[c]P, its 3,4-diol, and the 8,9 diols of the phenanthrothiophenes induced mutations primarily at AT sites. P[3,4-b]T was not mutagenic in TA104, whereas P[3,4-b]T sulfone was. The two isomeric forms (P[3,4-b]T and P[4,3-b]T) are apparently activated differently, with the latter, but not the former, involving a diol pathway. This study is the first illustrating the potential importance of abasic sites in the mutagenicity of thia-PAHs.

Keywords: Mutagenicity, Salmonella, Sulfur-PAH, DNA adducts

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocyclic compounds (PASH or thia-PAHs) are formed during the combustion of organic materials such as coal, oil, diesel fuel, and tobacco [1–5]. Like their more extensively studied relatives, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), thia-PAHs are mutagenic and carcinogenic [1, 4–7]. Thia-PAHs are considered to be more persistent in the environment than PAHs and, unlike most PAHs, they have the potential to bio-accumulate [1, 4]. However, despite their presence in many combustion emissions and urban air [1–5], relatively little is known about their biological effects.

The metabolites of benzo[b]naphtho[2,1-d]thiophene ([2,1]BNT) and benzo[b]phenanthro[2,3-d]thiophene include dihydrodiols with a bay-region double bond, as well as the sulfoxide and the sulfone [8,9]. In addition, [2,1]BNT-3,4-diol, which forms a bay-region diol epoxide, was as mutagenic in Salmonella TA100 as the parent compound [2,1]BNT; however, [2,1]BNT-1,2-diol was not mutagenic [10]. Thus, [2,1]BNT appears to be activated partially via a bay-region diol epoxide.

Thia-PAHs with a peripheral thiophene ring (thiophene-annulated PAHs) are also mutagenic [1,11], with the tri- and tetracyclic thia-PAHs of this class exhibiting higher mutagenic activity [1,11] compared to that of their carbon analogs [12,13]. Methyl-substituted tri- and tetracyclic thia-PAHs [7], as well as nitro-substituted tetracyclic sulfur-PAHs [14], are also mutagenic. The presence and position of the sulfur heteroatom in a PAH strongly influence the mutagenic and carcinogenic activity of thia-PAHs with a peripheral thiophene ring [1,11].

The metabolism of benzo[b]phenanthro[2,3-d]thiophene (BPT), a thia analog of dibenz[a,h]anthracene, has been studied [9]. BPT was mutagenic in Salmonella, causing primarily GC to TA mutations [15]. Although two of the major metabolites of BPT, BPT 3,4-diol and BPT sulfoxide, were more mutagenic than BPT, 3-hydroxyBPT and BPT sulfone were not mutagenic [15]. These results suggested the involvement of both a diol epoxide pathway and a sulfoxidation pathway in the bioactivation of thia-PAHs.

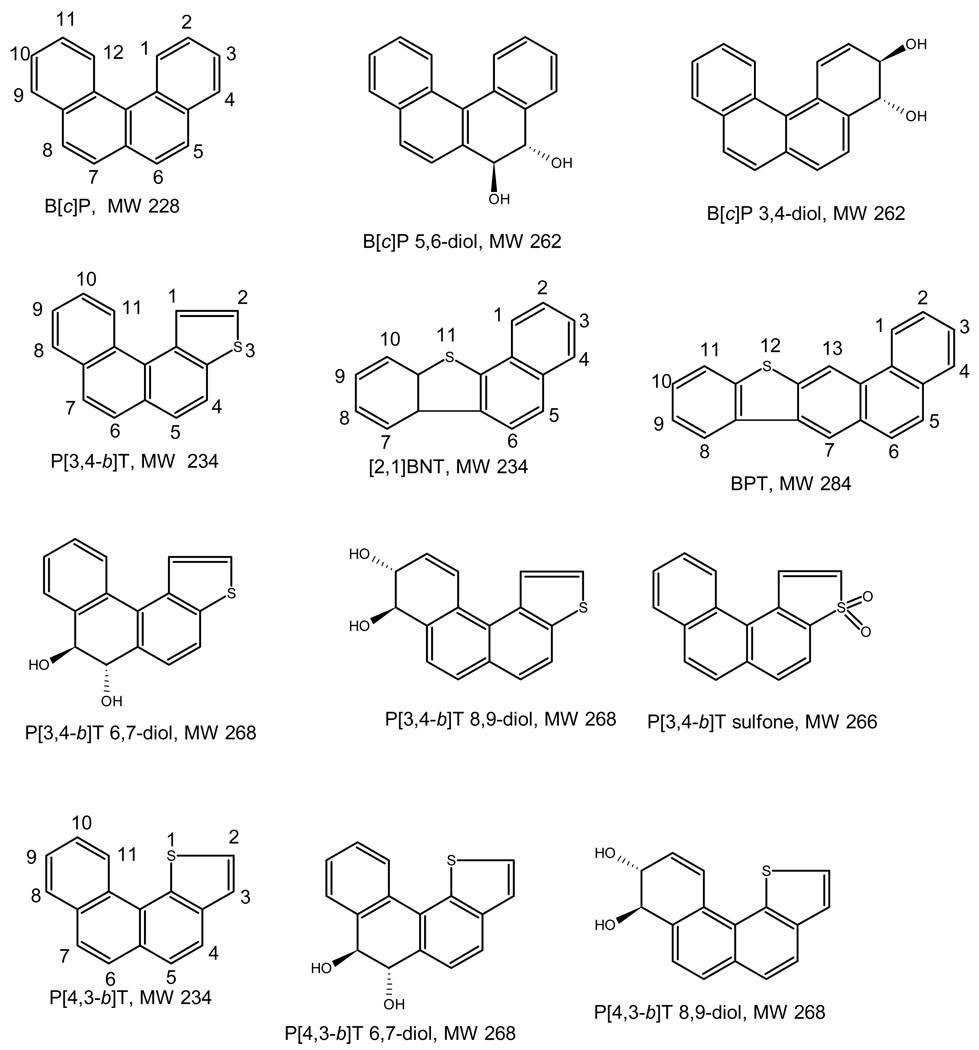

Early studies found that benzo[c]phenanthrene (B[c]P) and its 3,4-diol (B[c]P 3,4-diol) were mutagenic in Salmonella [13], as was phenanthro[3,4,-b]thiophene (P[3,4-b]T [11]. More recently, Kumar et al. [16] synthesized the dihydrodiol derivatives of P[3,4-b]T and phenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene (P[4,3-b]T) as well as the sulfone of the former. To examine the biological activities of these synthesized thia-PAHs, we determined the mutagenicity of nine thia-PAHs and B[c]P (Fig. 1, Table 1) in strains TA98, TA100, and TA104, as well as their relative potencies and their abilities to induce base-substitution and frameshift mutations. Comparison of mutagenic potencies of a compound in TA100 versus TA104 permits one to infer the site (AT or GC base pairs) specificity of the mutations induced by these compounds.

Figure 1.

Structures of PAHs, abbreviated name, and molecular weight.

Table 1.

Compounds evaluated for mutagenicity in the present study.

| Compound | Abbreviation | Reported Mutagenicity [ref] |

Number of mutagenicity assays |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA98 | TA100 | TA104 | |||

| Benzo[c]phenanthrenea | B[c]P | + [10] | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| (± )-trans-5,6-Dihydrobenzo[c]phenanthrene 5,6-diol | B[c]P 5,6-diol | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| (± )-trans-3,4-Dihydrobenzo[c]phenanthrene 3,4-diola | B[c]P 3,4-diol | + [10] | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Phenanthro[3,4,-b]thiophenea | P[3,4-b]T | + [11] | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| (± )-trans-6,7-Dihydrophenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene 6,7-diol | P[3,4-b]T 6,7-diol | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| (±)-trans-8,9-Dihydrophenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene 8,9-diola | P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Phenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene | P[4,3-b]T | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| (±)-trans-6,7-Dihydrophenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene 6,7-diol | P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| (±)-trans-8,9-Dihydrophenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene 8,9 diol-a | P[4,3-b]T 8,9 diol | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| Phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene sulfonea | P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

These compounds were also evaluated for induction of stable DNA adducts or abasic sites based on their mutagenicity in TA100 and TA104 and availability of compound.

Only one thia-PAH, 5-nitrobenzo[b]naphtho[2,1-d]thiophene, has been examined for its ability to induce stable DNA adducts [6], and no study has yet examined the ability of such compounds to induce abasic sites, which are one of the most frequent lesions in DNA. Abasic sites result from hydrolytic cleavage of the N-glycosyl bond between the base and deoxyribose. This cleavage can occur via spontaneous depurination or by the action of a DNA glycosylase during base-excision repair [17].

We assessed the ability of 6 of the compounds to induce stable DNA adducts, as measured by 32P-postlabeling, and abasic sites, as measured by an aldehydic-site assay [18], in strain TA100. We compared these results to the mutagenic potencies of the compounds in the various strains as well as to the inferred site-specificity of mutation to characterize potential mutagenic mechanisms and possible metabolic pathways of these compounds.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

B[c]P, its sulfur-containing analogs, and dihydrodiol and sulfone derivatives (Fig. 1) were synthesized as described and were obtained at >98% chemical purity by unequivocal synthesis [16,19,20]. For the synthesis of P[3,4-b-]T sulfone, a solution containing 100 mg of P[3,4-b-]T in 4 ml of CH2Cl2 containing 2 ml of trifluoroacetic acid was treated with 30% H2O2 at 0–5°C. After stirring at ambient temperature overnight, the product was isolated and purified by preparative TLC (30% EtOAc-hexane) to produce a light-yellow crystalline solid, mp 140–142°C. 1H NMR (DCCl3): d 6.96 (d, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.70–7.77 (m, 3 H), 7.85 (d, 1 H, J = 8.9 Hz), 7.92 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.93–7.99 (m, 1 H), 8.05 (d, 1 H, 8.0 Hz), 8.42 (d, 1 H, J = 7.3 Hz), 8.49–8.54 (m, 1 H); HRMS for C16H10O2S [M+]: 266.0396 (calculated); 266.0398 (EI found). Stock solutions of test compounds at 2 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Burdick and Jackson Laboratories, Muskegon, MI) were maintained at −20°C. Benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), sodium azide, and 2-aminoanthracene were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Nuclease P1 (NP1) and calf spleen phosphodiesterase (SPDE) were purchased from CalBiochem Corporation (La Jolla, CA). Polyethyleneimine cellulose (PEI-Cellulose) TLC plates were purchased from Alltech (Avondale, PA). Proteinase K, Ribonuclease A, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO), and Micrococcal nuclease (MN) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., (St. Louis, MO). Isopropanol (certified ACS grade) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh PA). HPLC-grade water and methanol were purchased from Burdick and Jackson Laboratories Inc. (Muskegon, MI). T4 polynucleotide kinase (3'-phosphatase free) was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). [γ32P]ATP (>3000 Ci/mmol) in an aqueous solution containing 5-mM 2-mercaptoethanol was obtained from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL). Flo-Scint II was obtained from Packard Bioscience, (Meriden, CT). The internal UV standard, cis-9,10-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene, was a gift from Dr. David H. Phillips, Haddow Laboratories, The Institute of Cancer Research (Sutton, Surrey, UK). All other chemicals were reagent grade and obtained from commercial sources.

Mutagenicity assays

The mutagenic potencies of the compounds (Table 1) were determined in the standard plate-incorporation assay in the Salmonella mutagenicity assay [21]. The strains used were TA98 [hisD3052 rfa-1004 chl-1008 (bio uvrB gal) pKM101+ Fels-1+ Fels-2+ Gifsy-1+ Gifsy-2+], TA100 [hisG46 rfa-1001 chl-1005 (bio uvrB gal) pKM101+ Fels-1+ Fels-2+ Gifsy-1+ Gifsy-2+], and TA104 [hisG428 rfa-1028 chl-1057 (bio uvrB gal) pKM101+ Fels-1+ Fels-2+ Gifsy-1+ Gifsy-2+], all provided by Dr. B.N. Ames, Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA. Aroclor 1254-induced, Sprague-Dawley rat liver S9 was obtained from Moltox, Inc. (Boone, NC). Initially, we tested each compound at doses of 2–80 µg/plate, but in replicate experiments, we restricted doses to the linear range of the dose-response curve. Pelroy et al. [11] showed that thia-PAHs require metabolic activation, so we tested all compounds in the presence of S9 mix. Because of its prior sulfoxidation, we also tested the sulfone derivative P[3,4-b]T sulfone without S9 mix to evaluate any direct-acting activity. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 37°C and counted with an AccuCount 1000 automated colony counter (BioLogics, Gainesville, VA). We calculated mutagenic potencies (rev/µg) as described below. Compounds showing reproducible dose-related increases in rev/plate that reached or exceeded 2-fold relative to zero-dose controls were considered mutagenic. The positive controls were B[a]P (at a range of doses to calculate a potency) for TA98 and TA100 with S9, 2-aminoanthracene (0.5 µg/plate) for TA104 with S9, and sodium azide (3 µg/plate) for TA100 and TA104 in the absence of S9.

Compounds B[c]P, B[c]P 3,4-diol, P[3,4-b]T, P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol, P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol, and P[3,4-b]T sulfone were selected for adduct analysis because, with the exception of P[3,4-b]T, these were the only compounds that were clearly mutagenic in both TA100 and TA104. P[3,4-b]T was included because it was highly mutagenic in TA100, although negative in TA104. Due to limited amount of some of these six compounds, there was enough to perform only one liquid-suspension mutagenicity assay for the adduct analyses. Thus, there was only one biological replicate for the adduct analyses.

To provide exposed cells from which to isolate DNA for adduct analysis, we evaluated these compounds for mutagenicity in TA100 using a liquid-suspension assay involving incubation of the cells, S9 mix, and compounds for 1.5 h at 37°C in 10- or 20-ml reactions. 20-ml reactions contained 14 ml of S9 mix, 5.5 ml of 10X overnight TA100 cells concentrated in PBS, and 500 µl of compound in DMSO at selected concentrations; 10-ml reactions contained half these amounts. Concentrations were selected based on mutagenic doses of the compounds in the plate-incorporation assay and on availability of compound. For mutagenicity, 50 µl were plated in duplicate on minimal medium supplemented with excess biotin and trace histidine; for survival, 100 µl was diluted 10−6 fold in PBS, and 100 µl was plated in duplicate on minimal medium supplemented with excess biotin and histidine. We concentrated the remaining cells by centrifugation, decanted the medium, and stored the cell pellet at −80°C until processed for DNA adduct analyses.

DNA isolation

DNA was isolated using the protocol and the PUREGENE DNA Purification Kit for 30–50 million cells (Qiagen Inc. Valencia, CA). The kit contained Purgene cell lysis solution (Cat # D-50K2), Purgene protein precipitation solution (Cat # D-50K3), and Purgene DNA hydration solution (Cat # D-50K4). We modified the manufacturer’s protocol to include the use of the antioxidant 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO), a free-radical scavenger [22]. TEMPO was suspended in methanol at 2 M and diluted into the above reagents to reach a final concentration of 20 mM. We removed 30 to 50 million cells in separate 50-ml centrifuge tubes from our −80°C freezer and thawed then at room temperature for 45 min. Then 6 ml of the cell lysis solution was added and the suspension mixed by pipetting the solution up and down several times to lyse cells. We then added 30 µl of Proteinase K solution (20 mg/ml), mixed well by inverting the samples in tubes up to 25 times, and incubated the samples for 1 hr at 37°C. Following this incubation, 30 µl of RNase A solution (4 mg/ml) was added to the lysate, and mixed as described and incubated again for 1 hr at 37°C. To precipitate the protein, 2 ml of the protein precipitation solution was added to the RNase-treated lysate, vortexed vigorously for 20 sec, and placed in the refrigerator at 4°C overnight. The following morning, the samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min to pellet the precipitated proteins. The supernatant containing the DNA was carefully poured into a 15-ml centrifuge tube containing 6 ml of 100% ice cold isopropanol. These samples were mixed by inverting 50 times and placed in a freezer at −20°C for 2 h to precipitate the DNA. The precipitated DNA was then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 3 min to pellet the DNA. The supernatant was decanted and the tubes drained on clean absorbent paper. To wash the DNA pellet, 6 ml of ice cold 70% ethanol was added, the tubes inverted several times, and the tubes centrifuged again at 2,000 × g for 1 min. The tubes were inverted to drain on clean absorbent paper to allow the samples to air dry for 10 to 15 min. The DNA was hydrated by the addition of 500 µl of DNA hydration solution and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. DNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer with ultraviolet absoption at wavelength A260. Isolated DNA was stored at −80°C until used for adduct analyses.

Detection of aldehydic lesions

To detect abasic sites in bacterial DNA samples, we used the BioVision DNA Damage Quantification Kit (BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA, Cat. No. K253-25) [18]. In the preparation of ARP-labeled DNA, we modified the manufacturer’s protocol by mixing 15 µl of genomic DNA (1µg/µl) in TE buffer (supplied with the kit) and 15 µl of ARP solution at the bottom of a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr to tag the DNA AP sites. We then added 8 µl of a glycogen solution and 600 µl of ice cold absolute ethanol, mixed well and placed in a freezer at −80°C for 20 min or overnight. To precipitate the AP-site tagged DNA, we centrifuged the samples in a microcentrifuge (Eppendorf Model 5417, Fisher Scientific, Inc. Pittsburgh, PA) at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed three additional times with 500 µl of ice cold absolute ethanol and centrifuged again after each wash at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The residual ethanol was removed and the pellet was allowed to dry at room temperature for 5 min. The ARP tagged DNA pellet was resuspended in 250 µl of TE Buffer and the DNA concentration quantified by using ultraviolet absorption at wavelength A260. The ARP tagged DNA samples were then diluted with TE buffer to yield a concentration of 0.5 µg/ml. The remainder of the procedures used in the determination of the number of abasic sites is DNA was as described in the DNA Damage Quantification Kit.

Detection of stable DNA adducts

We used the 32P-postlabeling assay to detect stable DNA adducts. The isolated DNA (50 µg) of each sample was digested to mononucleotides at 37°C for 3.5 h with MN and SPDE [6,23,24]. An internal standard of 5 µg of B[a]P-diol epoxide-modified calf thymus DNA was included in all adduct analyses. Digestion of 5 µg of modified calf thymus DNA yielded 9.5 × 106 dpm, which represented a 95% labeling efficiency.

DNA adducts were enriched by butanol extraction and evaporated to dryness in vacuo [6,23,24] due to the limited amount of sample and because butanol extracts a wider range of chemical classes than does nuclease P1. Samples were incubated with 50 µCi of [γ32P]ATP (>3000 Ci/mmol) and 3.5 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase for 30 min at 37°C, and total incubates were applied to PEI-cellulose TLC plates.

Labeled digests of DNA samples were spotted on 10-cm × 10-cm PEI-cellulose sheets and separated using a TLC system (D1 direction only) [6,23,24]. Following autoradiography to locate spots, samples were prepared for HPLC analyses [6,23,24]. Major PEI-cellulose adduct spots (1 cm2) were cut out and placed in scintillation vials containing 5 ml of ethanol, and total radioactivity was determined. Ethanol was decanted after counting, and adducted spots were extracted overnight (18 h) in 1 ml of 4-M pyridinium formate (pH 4). We transferred extracts to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge vials, and sedimented particulate material by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 1 min). Total radioactivity (DPM) in the 4-M pyridinium formate extracts was determined, and sample volumes were reduced to dryness in vacuo, resuspended with 100 µl of a 9:1 mixture of methanol:0.3-M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 2.0), vortexed, and centrifuged again (10,000 rpm, 1 min). Supernatant (75 µl) from each sample was carefully removed and spiked with 4 nmol (8 µl) of the UV marker, cis-9,10-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene. Volumes were adjusted to 100 µl with a 9:1 mixture of MeOH: 0.3-M NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 2) and placed in 100-µl autosampler vials for HPLC analysis.

We separated 32P-labeled nucleoside-3',5'-bisphosphate adducts on a Hewlett-Packard Series 1100 HPLC System (Hewlett-Packard Company, Wilmington, DE) using a 5-µm, 4.6-mm × 250-mm Zorbax phenyl-modified column (MAC-MOD Analytical, Inc., Chadds Ford, PA). Adducted nucleotides were eluted with a linear gradient using the following solvent system: Solvent A: 0.5-M NaH2HPO4 buffer (pH 2.0); Solvent B: 90% methanol and 10% solvent A. The gradient was 0 to 12.5 min, 10 to 43% B; 12.5 to 60 min, 43 to 47% B; 60 to 83 min, 47 to 90% B; 83 to 90 min, 10% B. Flow rate was 1 ml/min, and the column was allowed to equilibrate at the initial solvent ratio (90% A: 10% B) for 15 min before subsequent analysis. Radiolabeled nucleotides were detected by an in-line flow-through scintillation counter (Model A-500 Flow-One\β Radiomatic Instruments & Chemical Co., Inc. (Tampa, FL). The retention times of 32P-postlabeled DNA adducts were expressed as relative retention time (RRT), calculated by dividing the retention time of the 32P-postlabeled DNA adducts by the retention time of the internal UV standard (cis-9,10-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene). Adduct levels were estimated as described [25]. Chromatography was at pH 2, and our previous studies with other PAHs [6,23] as well as with these PAHs (data not shown) demonstrated that these adducts were stable at pH 2 based on a lower resolution and elution close to the front at pH 4 or 4.5.

Statistical analyses

Mutagenicity assays for each strain were conducted on separate sets of dates. For TA100 and TA104, only a subset of compounds was studied on each date; the number of dates per compound ranged from three to five for TA100 and from one to three for TA104. For TA98, all 10 compounds were assayed on each of three dates. Regardless of strain, each date involved triplicate plates at dose zero (common to all compounds studied on that date) and either single (on dose-finding runs) or duplicate plates (otherwise) at each non-zero dose for each compound. Consequently, for each strain and compound, we had from one to five ‘near-replicate’ dose-response curves (assays) with which to assess mutagenicity (Table 1).

We modeled the counts from each plate using generalized linear mixed models assuming a Poisson error distribution with the identity link function. To facilitate potency comparisons between TA100 and TA104, we analyzed these strains together, using a separate analysis for each compound. For those analyses, we modeled the expected response for each plate as a linear function of dose with a separate intercept and slope for each strain (omitting data outside the linear range). We considered date, interactions involving date, and replicate plates as possible sources of extra-Poisson variation. We analyzed TA98 separately from the other two strains but included all compounds in a single analysis. For this analysis, our model for the expected response includes a common intercept and separate slopes for each compound (omitting data outside the linear range). We again considered date, interactions involving date, and replicate plates as possible sources of extra-Poisson variation, and we allowed the magnitude of extra-variation parameters to differ among compounds.

The strain- and compound-specific slope parameters from these analyses represent the strain-specific potencies of the respective compounds (rev/µg). Our modeling approach appropriately integrates all individual experimental runs with possibly different numbers of dose levels and plates per dose to provide a single potency estimate for each compound in each strain. The variance reported for the potency estimates takes account of all sources of extra-Poisson variation mentioned earlier. We used SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), in particular the GLIMMIX macro, to fit these models <http://support.sas.com/ctx/samples/index.jsp?sid=536>.

Results

In general, the thia-PAHs were more potent base-substitution mutagens than frameshift mutagens (Table 2, Appendix A). Only P[3,4-b]T sulfone showed any significant activity in TA98, and its potency (143 rev/µg) was comparable to that of the positive control B[a]P (144 or 195 rev/µg in two experiments calculated independently by standard linear regression). In TA100, the sulfone also was the most mutagenic, followed by P[3,4-b]T. B[c]P 3,4-diol and P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol were moderately active. The most potent compounds in TA104 were B[c]P 3,4-diol, P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol, and P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol, whereas P[3,4-b]T and P[3,4-b]T sulfone were less potent in this strain (Table 2). Only P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol was not mutagenic in any strain.

Table 2.

Mutagenic potencies (rev/µg) ± S.E., call, and inferred predominant site of mutation in plate-incorporation assay

| Compound | Revertants/µg ± S.E. (call)a |

P (TA100 vs. TA104) | Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA98 | (call) | TA100 | (call) | TA104 | (call) | |||

| B[c]P | 1.2 ± 1.3 | (−) | 56.4 ± 12.1 | (+) | 241 ± 25 | (+) | 0.007 | A > G |

| B[c]P 5,6-diol | −0.1 ± 0.1 | (−) | 1.6 ± 0.7 | (+) | 2.5 ± 1.2 | (−) | 0.578 | only G |

| B[c]P 3,4-diol | 11.1 ± 3.0 | (+) | 268 ± 46 | (+) | 552 ± 62 | (+) | 0.014 | A > G |

| P[3,4-b]T | 0.2 ± 0.2 | (−) | 550 ± 61 | (+) | 210 ± 84 | (−) | 0.030 | only G |

| P[3,4-b]T 6,7-diol | 1.4 ± 0.2 | (+) | 59.8 ± 6.1 | (+) | 24.9 ± 8.3 | (−) | 0.043 | only G |

| P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 5.6 ± 0.8 | (+) | 80.0 ± 13.2 | (+) | 369 ± 28 | (+) | 0.003 | A > G |

| P[4,3-b]T | 13.7 ± 3.3 | (+) | 12.8 ± 3.9 | (+) | 58.9 ± 7.9 | (−) | 0.003 | only G |

| P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol | −0.2 ± 0.1 | (−) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | (−) | 9.2 ± 1.3 | (−) | 0.007 | negative |

| P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol | 11.0 ± 1.6 | (+) | 274 ± 37 | (+) | 577 ± 63 | (+) | 0.009 | A > G |

| P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 143 ± 19 | (+) | 914 ± 113 | (+) | 262 ± 135 | (+) | 0.034 | G > A |

Called mutagenic (+) based on showing reproducible, dose-related increases in rev/plate that reached or exceeded 2-fold relative to zero-dose controls; calls were not based on the magnitude of the potency relative to its standard error. Potencies were calculated as described in the Materials and methods based on the data in Appendix A.

Appendix A.

Mutagenicity of benzo[c]phenanthrene, B[c]P-related thiaarenes, and their derivatives in TA98, TA100, and TA104a

| Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 | Test 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test strain/ compound |

Dose (µg/plate) |

Rev/plate | Dose (µg/plate) |

Rev/plate | Dose (µg/plate) |

Rev/plate | Dose (µg/plate) |

Rev/plate | Dose (µg/plate) |

Rev/plate |

| TA98 | 0 | 33/40/39 | 0 | 43/41/30 | 0 | 49/50/50 | ||||

| B[c]P | 2 | 37 | 0.5 | 44/36 | 0.5 | 49/36 | ||||

| 5 | 43 | 1 | 41/35 | 1 | 52/54 | |||||

| 10 | 57 | 2 | 38/37 | 2 | 60/50 | |||||

| 20 | 60 | 5 | 56/50 | 5 | 87/61 | |||||

| 40 | 50 | |||||||||

| 80 | 35 | |||||||||

| B[c]P 5,6-diol | 2 | 31 | 10 | 43/42 | 10 | 51/47 | ||||

| 5 | 41 | 20 | 27/49 | 20 | 46/60 | |||||

| 10 | 41 | 40 | 46/33 | 40 | 51/47 | |||||

| 20 | 29 | 80 | 52/35 | 100 | 32/47 | |||||

| 40 | 34 | |||||||||

| 80 | 40 | |||||||||

| B[c]P 3,4-diol | 2 | 47 | 5 | 120/112 | 5 | 145/173 | ||||

| 5 | 100 | 10 | 180/199 | 10 | 238/242 | |||||

| 10 | 120 | 20 | 310/260 | 20 | 350/328 | |||||

| 20 | 226 | 40 | 460/414 | 40 | 458/504 | |||||

| 40 | 303 | 80 | 492/423 | 80 | 509/597 | |||||

| 80 | 417 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T | 2 | 81 | 0.05 | 30/40 | 0.05 | 57/49 | ||||

| 5 | 80 | 0.1 | 31/33 | 0.1 | 50/51 | |||||

| 10 | 62 | 0.25 | 33/32 | 0.25 | 40/63 | |||||

| 20 | 54 | 0.5 | 58/34 | 0.5 | 66/69 | |||||

| 40 | 60 | |||||||||

| 80 | 55 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T 6,7-diol | 2 | 45 | 20 | 64/63 | 20 | 90/111 | ||||

| 5 | 47 | 40 | 72/84 | 40 | 132/132 | |||||

| 10 | 61 | 80 | 146/141 | 80 | 181/199 | |||||

| 20 | 62 | 150 | 207/190 | 150 | 241/222 | |||||

| 40 | 107 | |||||||||

| 80 | 130 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 2 | 61 | 10 | 104/110 | 10 | 143/142 | ||||

| 5 | 87 | 20 | 124/134 | 20 | 193/190 | |||||

| 10 | 94 | 40 | 276/244 | 40 | 315/359 | |||||

| 20 | 156 | 80 | 381/323 | 80 | 448/459 | |||||

| 40 | 285 | |||||||||

| 80 | 412 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T | 2 | 61 | 1 | 39/49 | 1 | 93/74 | ||||

| 5 | 137 | 2 | 41/33 | 2 | 98/77 | |||||

| 10 | 141 | 5 | 97/77 | 5 | 162/166 | |||||

| 20 | 146 | 10 | 110/79 | 10 | 194/213 | |||||

| 40 | 158 | |||||||||

| 80 | 105 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol | 2 | 34 | 5 | 28/34 | 5 | 50/53 | ||||

| 5 | 35 | 10 | 27/28 | 10 | 43/47 | |||||

| 10 | 47 | 20 | 38/27 | 20 | 52/47 | |||||

| 20 | 52 | 40 | 33/27 | 40 | 48/50 | |||||

| 40 | 39 | |||||||||

| 80 | 36 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol | 2 | 73 | 10 | 167/151 | 10 | 251/249 | ||||

| 5 | 116 | 20 | 127/225 | 20 | 298/321 | |||||

| 10 | 140 | 40 | 383/448 | 40 | 561/624 | |||||

| 20 | 229 | 80 | 479/475 | 80 | 828/725 | |||||

| 40 | 435 | |||||||||

| 80 | 578 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 2 | 328 | 0.5 | 41/57 | 0.5 | 56/52 | ||||

| 5 | 982 | 1 | 63/67 | 1 | 124/86 | |||||

| 10 | 1373 | 2.5 | 263/237 | 2.5 | 293/366 | |||||

| 20 | 1324 | 5 | 765/708 | 5 | 1078/922 | |||||

| 40 | 1124 | |||||||||

| 80 | 1268 | |||||||||

| Positive control | 0.25 | 81/78 | 0.25 | 55/51 | 0.25 | 81/92 | ||||

| benzo[a]pyrene | 0.5 | 97/97 | 0.5 | 84/85 | 0.5 | 142/118 | ||||

| 1 | 138/130 | 1 | 158/160 | 1 | 217/240 | |||||

| 2 | 244/277 | 2 | 286/287 | 2 | 402/399 | |||||

| 3 | 283/247 | |||||||||

| TA100 | 0 | 99/110/110 | 0 | 84/78/80 | 0 | 127/118/125 | 0 | 112/140/115 | 0 | 102/119/99 |

| B[c]P | 2 | 251 | 0.5 | 97/85 | 0.5 | 180/190 | ||||

| 5 | 388 | 1 | 114/78 | 1 | 250/217 | |||||

| 10 | 467 | 2 | 117/143 | 2 | 300/303 | |||||

| 20 | 503 | 5 | 300/204 | 5 | 510/499 | |||||

| 40 | 494 | |||||||||

| 80 | 354 | |||||||||

| B[c]P 5,6-diol | 2 | 132 | 40 | 161/116 | 40 | 210/248 | ||||

| 5 | 151 | 80 | 129/144 | 80 | 306/328 | |||||

| 10 | 147 | 120 | 127/129 | 120 | 375/304 | |||||

| 20 | 192 | |||||||||

| 40 | 193 | |||||||||

| 80 | 263 | |||||||||

| B[c]P 3,4-diol | 2 | 694 | 0.5 | 151/162 | 0.5 | 335/357 | 0.5 | 328/304 | ||

| 5 | 1002 | 1 | 244/241 | 1 | 474/494 | 1 | 613/577 | |||

| 10 | 1067 | 2.5 | 533/604 | 2.5 | 848/945 | 2.5 | 938/941 | |||

| 20 | 942 | 5 | 598/153 | 5 | 1216/1218 | 5 | 1117/1140 | |||

| 40 | 381 | |||||||||

| 80 | 100 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T | 0.05 | 131/124 | 0.05 | 151/163 | 0.05 | 144/123 | 0.05 | 136/140 | ||

| 0.1 | 120/128 | 0.1 | 187/201 | 0.1 | 159/169 | 0.1 | 175/132 | |||

| 0.25 | 235/243 | 0.25 | 344/311 | 0.25 | 216/227 | 0.25 | 237/166 | |||

| 0.5 | 389/354 | 0.5 | 450/508 | 0.5 | 333/364 | 0.5 | 366/305 | |||

| P[3,4-b]T 6,7-idol | 2 | 280 | 2 | 224/217 | 2 | 305/298 | ||||

| 5 | 461 | 5 | 369/364 | 5 | 573/564 | |||||

| 10 | 580 | 10 | 746/565 | 10 | 862/714 | |||||

| 20 | 1052 | 20 | 593/607 | 20 | 1142/1113 | |||||

| 40 | 1172 | |||||||||

| 80 | 1286 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 2 | 326 | 0.5 | 80/94 | 0.5 | 147/151 | ||||

| 5 | 554 | 1 | 140/116 | 1 | 178/187 | |||||

| 10 | 755 | 2.5 | 268/224 | 2.5 | 347/430 | |||||

| 20 | 995 | 5 | 352/315 | 5 | 545/614 | |||||

| 40 | 992 | |||||||||

| 80 | 847 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T | 2 | 172 | 1 | 80/84 | 1 | 142/160 | 1 | 160/156 | ||

| 5 | 194 | 2 | 92/89 | 2 | 185/164 | 2 | 164/156 | |||

| 10 | 190 | 5 | 116/108 | 5 | 218/248 | 5 | 218/198 | |||

| 20 | 125 | 10 | 119/98 | 10 | 274/291 | 10 | 275/234 | |||

| 40 | 188 | |||||||||

| 80 | 164 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol | 2 | 101 | 5 | 97/98 | 5 | 125/135 | ||||

| 5 | 128 | 10 | 79/88 | 10 | 132/119 | |||||

| 10 | 126 | 20 | 94/113 | 20 | 134/155 | |||||

| 20 | 127 | 40 | 119/81 | 40 | 136/128 | |||||

| 40 | 132 | |||||||||

| 80 | 137 | |||||||||

| P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol | 2 | 660 | 0.5 | 205/219 | 0.5 | 412/353 | 0.5 | 305/312 | 0.5 | 269/235 |

| 5 | 938 | 1 | 318/270 | 1 | 610/511 | 1 | 487/469 | 1 | 430/375 | |

| 10 | 1120 | 2.5 | 703/655 | 2.5 | 951/868 | 2.5 | 976/966 | 2.5 | 865/878 | |

| 20 | 1175 | 5 | 857/907 | 5 | 985/1059 | 5 | 1368/1275 | 5 | 1150/1115 | |

| 40 | 1027 | |||||||||

| 80 | 673 | |||||||||

| P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 0.1 | 239/190 | 0.1 | 197/195 | 0.1 | 194/197 | ||||

| 0.25 | 368/365 | 0.25 | 284/297 | 0.25 | 255/245 | |||||

| 0.5 | 681/795 | 0.5 | 453/514 | 0.5 | 504/448 | |||||

| 1 | 1332/1283 | 1 | 380/383 | 1 | 1037/993 | |||||

| 2.5 | 2801/2710 | 2.5 | 1885 | 2.5 | 2935/2875 | |||||

| 5 | 3090/3170 | |||||||||

| Positive control | 0.25 | 283/295 | 0.25 | 141/145 | 0.25 | 245/232 | 0.25 | 416/384 | 0.25 | 300/296 |

| benzo[a]pyrene | 0.5 | 434/467 | 0.5 | 247/220 | 0.5 | 442/503 | 0.5 | 616/641 | 0.5 | 505/525 |

| 1 | 641/677 | 1 | 382/317 | 1 | 665/972 | 1 | 955/850 | 1 | 794/808 | |

| 2 | 1053/1132 | 2 | 604/490 | 2 | 945/1250 | 2 | 1202/1255 | 2 | 1062/1044 | |

| 3 | 1258/1210 | |||||||||

| TA104 | 0 | 379/400/370 | 0 | 276/260/270 | 0 | 402/395/336 | 0 | 482/455/462 | ||

| B[c]P | 0.5 | 432/407 | 0.5 | 523/486 | ||||||

| 1 | 504/506 | 1 | 636/581 | |||||||

| 2 | 570/609 | 2 | 588/660 | |||||||

| 5 | 753/894 | 5 | 850/824 | |||||||

| B[c]P 5,6-diol | 40 | 457 | ||||||||

| 80 | 506 | |||||||||

| 120 | 507 | |||||||||

| B[c]P 3,4-diol | 0.5 | 770/707 | 0.5 | 663/615 | 0.5 | 655/635 | ||||

| 1 | 1007/1137 | 1 | 923/920 | 1 | 913/888 | |||||

| 2.5 | 1618/1616 | 2.5 | 1368/1509 | 2.5 | 1375/1312 | |||||

| 5 | 1925/2036 | 5 | 1781/1775 | 5 | 1807/1818 | |||||

| P[3,4-b]T | 0.5 | 335/385 | 0.5 | 507/473 | ||||||

| 1 | 461/542 | 1 | 571/559 | |||||||

| 2 | 569/553 | 2 | 604/630 | |||||||

| 5 | 582/601 | 5 | 535/679 | |||||||

| P[3,4-b]T 6,7-idol | 2 | 365/338 | 2 | 475/419 | ||||||

| 5 | 407/431 | 5 | 498/541 | |||||||

| 10 | 475/484 | 10 | 532/550 | |||||||

| 20 | 538/576 | 20 | 533/627 | |||||||

| P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 0.5 | 486/465 | 0.5 | 566/525 | ||||||

| 1 | 213/673 | 1 | 754/785 | |||||||

| 2.5 | 1311/1300 | 2.5 | 1235/1287 | |||||||

| 5 | 1723/1755 | 5 | 1508/1620 | |||||||

| P[4,3-b]T | 1 | 392/313 | 1 | 457/397 | 1 | 517/524 | ||||

| 2 | 414/432 | 2 | 468/515 | 2 | 532/540 | |||||

| 5 | 419/440 | 5 | 490/505 | 5 | 540/497 | |||||

| 10 | 437/473 | 10 | 489/509 | 10 | 520/592 | |||||

| P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol | 5 | 330/353 | 5 | 438/407 | ||||||

| 10 | 391/347 | 10 | 442/462 | |||||||

| 20 | 348/340 | 20 | 423/445 | |||||||

| 40 | 305/354 | 40 | 365/373 | |||||||

| P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol | 0.5 | 700/693 | 0.5 | 824/707 | ||||||

| 1 | 1035/1060 | 1 | 1210/1178 | |||||||

| 2.5 | 1698/1615 | 2.5 | 1827/1822 | |||||||

| 5 | 1986/1995 | 5 | 1980/1970 | |||||||

| P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 2.5 | 1068/1015 | 2.5 | 1027/982 | ||||||

| 5 | 1603/1565 | 5 | 1650/1580 | |||||||

| 10 | 1488/1583 | 10 | 1652/1652 | |||||||

| 20 | 706/778 | 20 | 758/919 | |||||||

| Positive control | 0.1 | 469/478 | 0.1 | 366/337 | 0.1 | 444/419 | 0.1 | 573/564 | ||

| 2-aminoanthracene | 0.25 | 650/632 | 0.25 | 521/530 | 0.25 | 570/588 | 0.25 | 699/711 | ||

| 0.5 | 849/818 | 0.5 | 764/666 | 0.5 | 822/811 | 0.5 | 864/989 | |||

| 1 | 1004/998 | 1 | 983/956 | 1 | 1079/1097 | 1 | 1185/1181 | |||

| 2 | 1335/1432 | 2 | 1321/1392 | 2 | 1434/1518 | |||||

Numbers in bold identify linear portions of the dose-response curves, and duplicate or triplicate plate values are separated by a / mark.

Mutations can be recovered in TA100 only at GC sites, but mutations can be recovered in TA104 at either GC or AT sites. Thus, comparing the mutagenic potencies of the compounds in these two base-substitution strains permits one to infer the mutational specificity of the compounds. This analysis showed that four compounds, B[c]P 5,6-diol, P[3,4-b]T, P[3,4-b]T 6,7-diol, and P[4,3-b]T, were mutagenic only in strain TA100, indicating that they produced mutations at only GC sites (Table 2). In contrast, another four compounds, B[c]P, B[c]P 3,4-diol, P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol, and P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol, were more mutagenic in TA104 than in TA100, indicating that they produced mutations preferentially at AT sites relative to GC sites. Among compounds that were mutagenic in both TA100 and TA104, only the sulfone was more mutagenic in TA100 than in TA104, indicating that it produced mutations preferentially at GC sites relative to AT sites.

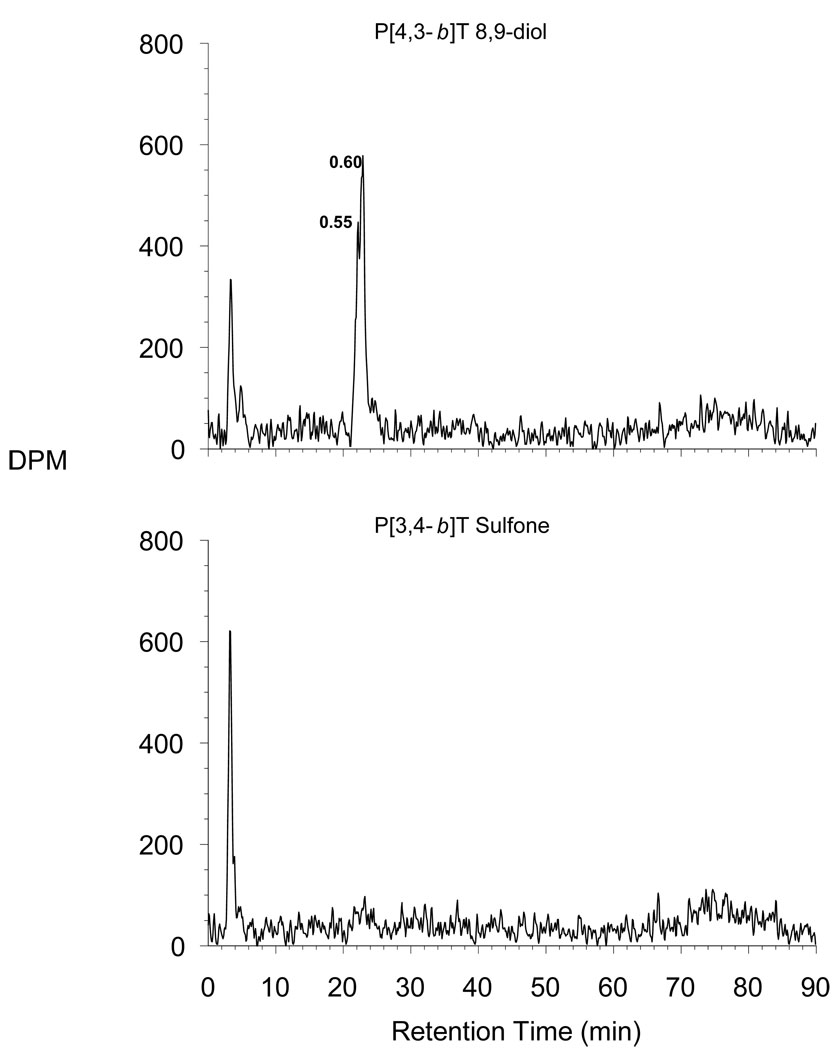

Except for the sulfone, all of the compounds produced stable DNA adducts, whereas only the sulfone produced abasic sites at levels that were twofold or greater than those detected in the DMSO control (Table 3; Fig. 2). We saw no obvious relationship between the mutagenic potencies and the levels of DNA adducts or between percent survival and the levels of DNA adducts (Table 3). As in the plate-incorporation assay, the sulfone was also the most mutagenic compound in the liquid-suspension assay (Table 3). Thus, the high mutagenic activity of the sulfone was associated with the induction of abasic sites and not with stable DNA adducts.

Table 3.

Mutagenicity, DNA adducts, and abasic sites induced by compounds in strain TA100 in liquid-suspension assay

| Compound | Concen. (µg/ml) |

Percent survival |

Rev/106 survivors |

Fold increasea |

Stable adducts/ 108 nucleotides ± S.Eb |

Abasic sites/ 105 nucleotides ± S.Ec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO (0.025 ml/ml) | 100 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.024 ± 0.000 | 5.9 ± 0.33 | |

| B[c]P | 20 | 71 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 1.600 ± 0.040 | 3.3 ± 0.12 |

| B[c]P 3,4-diol | 2 | 56 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 5.900 ± 0.230 | 4.2 ± 0.16 |

| 5 | 20 | 18.7 | 23.4 | 4.500 ± 0.034 | 5.3 ± 0.27 | |

| P[3,4-b]T | 10 | 24 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 0.090 ± 0.007 | 6.2 ± 0.26 |

| P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol | 2 | 91 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 0.170 ± 0.045 | 2.9 ± 0.23 |

| 5 | 63 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.750 ± 0.045 | 4.7 ± 0.25 | |

| P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol | 5 | 47 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 0.650 ± 0.045 | 5.5 ± 0.16 |

| P[3,4-b]T sulfone | 10 | 56 | 14.1 | 17.6 | Not detected | 18.4 ± 0.64 |

| 20 | 37 | 49.1 | 62.1 | Not detected | 15.1 ± 0.43 |

Fold increase in mutant frequency relative to that of DMSO-treated cells.

Average and standard error are based on two subsamples from a single biological sample for each compound. These standard errors represent technical measurement error only and should not be used to assess differences among compounds.

Average and standard error are based on triplicate measurements on each of three subsamples from a single biological sample for each compound. These standard errors represent technical measurement error only and should not be used to assess differences among compounds.

Figure 2.

Typical HPLC profile of DNA from Salmonella TA100 treated with P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol or P[3,4-b]T sulfone.

Discussion

Consistent with the literature [13], the mutagenic potency of the non-sulfur-containing parent PAH B[c]P was considerably less than that of its 3,4-diol, and the 5,6-diol was barely mutagenic (Table 2). A similar effect was seen for P[4,3-b]T and its diol derivatives, where the mutagenic potency of P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol was greater and that of P[4,3-b]T 6,7-diol was less than that of their parent compound P[4,3-b]T (Table 2). The pattern for P[3,4-b]T and its diols also was similar, except that the 8,9-diol was more mutagenic than the parental compound in TA98 and TA104 but not in TA100. These results illustrate a generally consistent and large influence of the location of the diol on mutagenic potency relative to the parent compound.

In agreement with a previous study [11], we found that the mutagenic potency of the thia-PAHs depended on the position of the sulfur heteroatom relative to the vicinal trans-diol group. For example, the mutagenicity of P[3,4-b]T, where the sulfur atom is distal to the angular benzo-ring, was similar to that of its parent compound B[c]P in TA104 but much greater than that of its parent in TA100. In contrast, the mutagenicity of P[4,3-b]T, where the sulfur atom is proximal to the angular benzo-ring, was much less than that of B[c]P in both strains. This observation may reflect the greater steric availability of the sulfur atom for metabolic activation when the sulfur atom is distal rather than proximal to the angular benzo-ring. The K-region diols (6,7-diols) were the least mutagenic diols and were consistently less mutagenic than their respective parent compounds (Table 2). The sulfone required metabolic activation to be mutagenic, which raises a question as to the ultimate mutagenic form of these sulfur-PAHs. As shown previously for B[c]P and B[c]P 3,4-diol ([10] and for the sulfone here and elsewhere [11], metabolic activation was required for the mutagenicity of these compounds. The other seven compounds were mutagenic in the presence of S9 mix (Table 2); however, we were unable to test them in the absence of S9 mix due to limited availability of sample. Nonetheless, based on earlier studies showing that other sulfur-PAHs required S9 mix to be mutagenic [11], it is likely that these seven sulfur-PAHs also require S9 mix for mutagenic activity.

The most mutagenic thia-PAH, the sulfone, produced the most abasic sites and was the only compound that induced mutation at primarily GC sites and a high level of frameshift mutation. In contrast, four of the five remaining compounds that were next in mutagenic potency (i.e., the parent PAH B[c]P, its 3,4-diol, and the 8,9 diols of the two phenanthrothiophenes) all produced only stable DNA adducts resulting in mutations primarily at AT sites. The exception, P[3,4-b]T, induced mutation only at GC sites. Our finding that B[c]P 3,4-diol, which was more mutagenic than the parent B[c]P in all strains of Salmonella, produced more stable DNA adducts and was more mutagenic than its parent compound B[c]P is consistent with a diol epoxide mechanism of mutagenicity for B[c]P in Salmonella. Because P[3,4-b]T sulfone induced only abasic sites, and more than twice the levels produced by P[3,4-b]T, then the sulfone is, apparently, not a major metabolite of P[3,4-b]T. In contrast, P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol produced more stable DNA adducts than its parent P[3,4-b]T, consistent with metabolic activation of P[3,4-b]T to the diol and then to the diol epoxide in TA104. P[3,4-b]T 8,9-diol was, however, considerably less mutagenic in TA100 than its parent compound P[3,4-b]T, suggesting that unlike B[c]P, its sulfur analogue P[3,4-b]T is metabolically activated (or metabolized to mutagenic products) by several pathways.

A preliminary metabolism study [26] involving incubation of selected compounds with rat liver microsomes found that the 6,7-diols (K-region diols) and 8,9-diols (diols with a bay-region double bond) were formed at considerably lower levels from P[3,4-b]T and P[4,3-b]T compared to the levels that the analogous 5,6-diol (K-region diol) and 3,4-diol (diol with a bay-region double bond) were formed from B[c]P. A major (80–96% of the total metabolites), relatively nonpolar metabolite(s) was formed by both P[3,4-b]T and P[4,3-b]T.

The formation of extremely low or undetectable amounts of P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol [24], which is 10–20 times more mutagenic for base-substitution mutation than the parent P[4,3-b]T (Table 2), is consistent with the possible involvement of a dihydrodiol pathway in the metabolic activation of P[4,3-b]T. Thus, P[4,3-b]T 8,9-diol is a proximate (not ultimate) mutagenic form of P[4,3-b]T. These mutagenicity data suggest the possibility that the ultimate mutagenic form is a diol expode formed from the 8,9-diol. P[3,4-b]T, which is highly mutagenic in TA100, is also metabolized to a lower extent than B[c]P [24]. However, in addition to low formation, this diol is also 7 times less mutagenic (in TA100) than its parental form (P[3,4-b]T). These observations suggest that in contrast to P[4,3-b]T, P[3,4-b]T is activated via a mechanism other than a diol epoxide pathway. Collectively, these data indicate that the two isomeric forms (P[3,4-b]T and P[4,3-b]T), which differ only in the position of the sulfur heteroatom, are metabolically activated by distinctly different pathways, with P[3,4-b]T not involving a diol pathway but the P[4,3-b]T likely involving a diol epoxide pathway.

The fact that the most mutagenic compound (the sulfone) produced the most abasic sites, whereas the less-mutagenic compounds produced more stable DNA adducts, illustrates the potential importance of aldehydic lesions in the mutagenesis of thia-PAHs, as has already been shown for other PAHs [27]. The most common model for the conversion of an abasic site to a base substitution mutation (as produced by the sulfone in TA100 and TA104) involves the “A-rule,” in which dATP is incorporated preferentially opposite an abasic site by various DNA polymerases [28]. Additional models have been proposed for the conversion of abasic sites into frameshift mutations [29], which also were induced at a high level by the sulfone. Our data indicate that metabolism of the sulfone by S9 mix results in a highly reactive intermediate that results in mutations preferentially at guanine, and to a lesser extent to adenine (Table 2). Recent studies indicate that the mutations initiated by abasic lesions are a consequence of the nature of the lesion, the structure of neighboring nucleotides, and the type of DNA polymerase that performs translesion synthesis [28].

All three benzo-ring dihydrodiols, as well as the parent compound B[c]P, induced stable DNA adducts, and they induced mutations preferentially at AT sites rather than GC sites (Table 2). These were the only compounds to exhibit this type of site specificity for mutation, and this study clearly links the structure of benzo-ring dihydrodiols to mutation induction preferentially at AT sites. In contrast, two of the K-region dihydrodiols, B[c]P 5,6-diol and P[3,4-b]T 6,7-diol, as well as the parent compounds P[3,4-b]T and P[4,3-b]T, induced mutations only at GC sites, and they were the only compounds that exhibited this site specificity for mutation (Table 2). P[3,4-b]T induced stable DNA adducts, but a limited amount of sample prevented our assessing P[4,3-b]T for induction of stable DNA adducts. Collectively, our results begin to define the structural features of these compounds that are associated with site specificity of mutation (and, presumably, site specificity of DNA damage), as well as the nature of the lesion (stable adducts or abasic sites).

Because of their persistence and multiple pathways of bioactivation, thia-PAHs may contribute substantially to the mutagenicity of complex mixtures in which they occur. Further studies are required to clarify their metabolic pathways and the types of DNA damage and mutations they induce. In particular, studies on the carcinogenicity of selected thia-PAHs are needed to relate emerging mechanistic data to overall health effects in vivo for this important class of environmental contaminant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peggy Matthews for preparation of medium and Linda Adams and Joycelyn Allison for help with the DNA adduct analyses. We thank Jeffrey Ross, Larry Claxton, and Daniel Shaughnessy for helpful comments on the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. C.D.S. was supported by a grant from the NHEERL-DESE Cooperative Training Agreement in Environmental Science Research, US EPA CT 82651301. S.K. acknowledges support from Phillip Morris USA. This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. This manuscript has been reviewed by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents reflect the views of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

References

- 1.Jacob J. Sulfur Analogues of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (Thia-arenes) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 1–281. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson JT, Hegazi AH, Roberz B. Polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles as information carriers in environmental studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006;386:891–905. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang F, Lu M, Birch ME, Keener TC, Liu Z. Determination of polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles in diesel particulate matter and diesel fuel by gas chromatography with atomic emission detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1114:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kropp KG, Fedorak PM. A review of the occurrence, toxicity, and biodegradation of condensed thiophenes found in petroleum. Can. J. Microbiol. 1998;44:605–622. doi: 10.1139/cjm-44-7-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claxton LD, Matthews PP, Warren SH. The genotoxicity of ambient outdoor air, a review: Salmonella mutagenicity. Mutation Res. 2004;567:347–399. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King LC, Kohan MJ, Brooks L, Nelson GB, Ross JA, Allison J, Adams L, Desai D, Amin S, Padgett W, Lambert GR, Richard AM, Nesnow S. An evaluation of the mutagenicity, metabolism, and DNA adduct formation of 5-nitrobenzo[b]naphtho[2,1-d]thiophene. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:661–671. doi: 10.1021/tx0001373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFall T, Booth GM, Lee ML, Tominaga Y, Pratap R, Tedjamulia M, Castle RN. Mutagenic activity of methyl-substituted tri-and tetracyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles. Mutation Res. 1984;135:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(84)90161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy SE, Amin S, Coletta K, Hoffmann D. Rat liver metabolism of benzo[b]naphtho[2,1-d]thiophene. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992;5:491–495. doi: 10.1021/tx00028a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan Z-X, Sikka H, Munir S, Kumar A, Muruganandam AV, Kumar S. Metabolism of the polynuclear sulfur heterocycle benzo[b]phenanthro[2,3-d]thiophene by rodent liver microsomes: evidence for multiple pathways in the bioactivation of benzo[b]phenanthro[2,3-d]thiophene. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16:1581–1588. doi: 10.1021/tx0341310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misra B, Amin S. Synthesis and mutagenicity of trans-dihydrodiol metabolites of benzo[b]naphtho[2,1-d]thiophene. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1990;3:93–97. doi: 10.1021/tx00014a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelroy RA, Stewart DL, Tominaga Y, Iwao M, Castle RN, Lee ML. Microbial mutagenicity of 3-and 4-ring polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles. Mutation Res. 1983;117:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(83)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood AW, Chang RL, Levin W, Ryan DE, Thomas PE, Mah HD, Karle JM, Yagi H, Jerina DM, Conney AH. Mutagenicity and tumorigenicity of phenanthrene and chrysene epoxides and diol epoxides. Cancer Res. 1979;39:4069–4077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood AW, Chang RL, Levin W, Ryan DE, Thomas PE, Croisy-Delcey M, Ittah Y, Yagi H, Jerina DM, Conney AH. Mutagenicity of the dihydrodiols and bay-region diol-epoxides of benzo(c)phenanthrene in bacterial and mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2876–2883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laali KK, Chun J-H, Okazaki T, Kumar S, Borosky GL, Swartz C. Electrophilic chemistry of thia-PAHs: stable carbocations (NMR and DFT), S-alkylated onium salts, model electrophilic substitutions (nitration and bromination), and mutagenicity assay. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8383–8393. doi: 10.1021/jo701502y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Lin J-M, Whysner J, Sikka H, Amin S. Mutagenicity of benzo[b]phenanthro[2,3-d]thiophene (BPT) and its metabolites in TA100 and base-specific tester strains (TA7001-TA7006) of Salmonella typhimurium: evidence of multiple pathways for the bioactivation of BPT. Mutation Res. 2004;545:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(03)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Reuben PA, Kumar A. Synthesis of dihydrodiols of phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene and phenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene. Polycyclic Aromatic Compds. 2004;24:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59 2552-2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao R, Su Y, Simmen RCM, Simmen FA. Dietary soy protein inhibits DNA damage and cell survival of colon epithelial cells through attenuated expression of fatty acid synthase. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G868–G876. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Saravanan S, Reuben P, Kumar A. Synthesis of trans-dihydrodiol derivatives of phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene and phenanthro[4,3-b]thiophene. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2005;42:1345–1355. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S. A new and concise synthesis of 3-hydroxybenzo[c]phenanthrene and 12-hydroxybeno[g]chrysene, useful intermediates for the synthesis of fjord-region diol epoxides of benzo[c]phenanthrene and benzo[g]chrysene. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8535–8539. doi: 10.1021/jo9712355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maron DM, Ames BN. Revised methods for the Salmonella mutagenicity test. Mutation Res. 1983;113:173–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(83)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDorman KS, Pachowski BF, Nakamura J, Wolf DC, Swenberg JA. Oxidative DNA damage from potassium bromate exposure in Long-Evans rats is not enhanced by a mixture of drinking water disinfection by-products. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 2005;152:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King LC, George M, Gallagher JE, Lewtas J. Separation of 32P-postlabeled DNA adducts of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by HPLC. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994;7:503–510. doi: 10.1021/tx00040a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weyand DH, Rice JD, LaVoie EJ. 32P-Postlabeling analysis of DNA adducts from non-alternant PAH using thin-layer and high performance liquid chromatography. Cancer Lett. 1987;37:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(87)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King LC, Adams L, Allison JC, Kohan MJ, Nelson G, Desai D, Amin S, Ross J. A quantitative comparison of dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-DNA adduct formation by recombinant human cytochrome P450 microsomes. Mol. Carcinogen. 1999;26:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Kumar A, Sikka HC. Comparative metabolism of phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene, phenanthro[3,4-b]thiophene and their carbon analog benzo[c]phenanthrene by rat liver microsomes. Polycyclic Aromatic Compds. 2004;24:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakravarti D, Venugopal D, Mailander PC, Meza JL, Higginbotham S, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. The role of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in inducing mutations in mouse skin. Mutation Res. 2008;649:161–178. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor J-S. New structural and mechanistic insight into the A-rule and the instructional and non-instructional behavior of DNA photoproducts and other lesions. Mutation Res. 2002;510:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroeger KM, Kim J, Goodman MF, Greenberg MM. Replication of an oxidized abasic site in Escherichia coli by a dNTP-stabilized misalignment mechanism that reads upstream and downstream nucleotides. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5048–5056. doi: 10.1021/bi052276v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]