Abstract

To assess whether infants hospitalized after an apparently life-threatening event had an associated respiratory virus infection, we analyzed nasopharyngeal aspirates from 16 patients. Nine of 11 infants with positive virus results were infected by rhinoviruses. We detected the new genogroup of rhinovirus C in 6 aspirates.

Keywords: Picornavirus, rhinovirus, HRV-C, infants, apparent life-threatening events, viruses, dispatch

Human rhinovirus (HRV) is 1 of the most common agents associated with upper and lower respiratory tract infections in children and infants (1) and is a major trigger of asthma exacerbations (2). Recently, molecular methods have shown substantial phenotypic variation of HRV and identified a novel HRV genogroup provisionally named HRV-C (3). Severe asthma exacerbations in children have been associated with this new genogroup of rhinoviruses. Genogroup C could be resistant to a new candidate group of antipicornavirus drugs, including pleconaril (4).

Apparently life-threatening events (ALTEs) in infants are associated with bronchiolitis or infections in up to 6% of patients by diagnosis after hospital admission (5). We assessed the relation between ALTEs and respiratory virus infection in a secondary hospital in Spain.

The Study

Our study was part of a systematic prospective study to assess the epidemiology of respiratory virus infections in children admitted to the Severo Ochoa Hospital (Leganés, Madrid Province, Spain).We conducted a specific study to determine the incidence of respiratory virus infections in all infants admitted after ALTEs during November 2004–December 2008. An ALTE in a child <1 year of age was defined as an episode that is frightening to the observer and characterized by some combination of apnea, color change, marked change in muscle tone, choking, or gagging so the observer fears the infant has died (6).

Nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) specimens were acquired from each eligible patient at the time of hospital admission (on Monday–Friday). Samples were sent for virologic study to the Influenza and Respiratory Virus Laboratory (National Centre for Microbiology, Institute of Health Carlos III, Spain). Specimens were processed within 24 hours after collection.

Total nucleic acids were extracted from 200-µL aliquots by using a QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit in a QIAcube automated extractor (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). Simple or multiplex reverse transcription–nested PCR assays (RT-PCR) previously described (7–9) were used to assess the virus diagnosis, including 16 respiratory viruses or groups of viruses. Degenerated primers for HRV and enteroviruses were designed between the 3′ end of the 5′ noncoding region (NCR) and the viral protein (VP) 4/VP2 polyprotein gene (TCIGGIARYTTCCASYACCAICC-3′ and CTGTGTTGAWACYTGAGCICCCA-3′). HRVs from positive samples were identified by sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of these sequences. Amplified products (about 500 bp, depending on HRV serotype) were purified and sequenced in both directions by using an automated ABI PRISM 377 model sequencer. Partial sequences of HRV have been submitted to GenBank (accession nos. FJ841954–FJ841957, FJ841959–FJ841961, EU697826, and EU697832). Appropriate precautions were implemented to avoid false-positive results by carryover contamination. Positive results were confirmed by testing a second aliquot of the sample stored at –70ºC.

Sixteen infants (8 of each sex) were enrolled in the study. All patients were <5 months of age (range 7 days–5 months, mean age 7.6 weeks, median 4 weeks). Twelve infants had rhinorrea, cough, and distress signs (Table). A total of 11 (69%) NPA specimens were positive for at least 1 viral agent. For 9 of these patients, positive results for HRV were confirmed, and for the other 2 patients, respiratory syncytial virus was detected.

Table. Characteristics of infants with ALTEs, Spain, November 2004–December 2008*.

| Laboratory no. | Sex/age, wk | Admission date | Clinical signs | Discharge diagnosis | Virus | Prematurity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO3970 | M/4 | 2004 Nov | Cough, rhinorrea, loss of consciousness, flaccidity | Choking | HRV-B | No |

| SO4891 | M/4 | 2005 Oct | Cyanosis, loss of consciousness, flaccidity | Cyanosis | No | Yes (35 wk) |

| SO4923 | M/15 | 2005 Nov | Apnea, flushing | Cyanosis + URTI | HRV-A | Yes (36 wk) |

| SO4998 | F/8 | 2005 Nov | Choking, flushing, distress | URTI + GERD | HRV-B | No |

| SO5260 | F/9 | 2006 Apr | Cough, choking | GERD | No | No |

| SO5355 | M/6 | 2006 Jun | Apnea, cyanosis | URTI + GERD | No | No |

| SO5529 | F/4 | 2006 Nov | Apnea, congestion, cyanosis | Bronchiolitis + GERD | RSV | No |

| SO5749 | M/24 | 2007 Mar | Choking, cyanosis | Wheezing | No | No |

| SO5797 | F/6 | 2007 Mar | Apnea, flushing | Choking + GERD | HRV-C | No |

| SO5854 | F/6 | 2007 Apr | Cough, rhinorrea, apnea | URTI + GERD | HRV-C | No |

| SO5896 | M/13 | 2007 Sep | Apnea, rhinorrea | Bronchiolitis + GERD | HRV-C | No |

| SO6012 | F/7 | 2007 Oct | Cough, distress, apnea | URTI | RSV-A | No |

| SO6666 | M/4 | 2008 Oct | Cyanosis, choking | Choking | HRV-C | No |

| SO6813 | F/6 | 2008 Nov | Apnea, flaccidity | Apnea + GERD | HRV-C | No |

| SO6819 | M/6 | 2008 Nov | Cough, rhinorrea, flushing | URTI + GERD | HRV-C | No |

| SO6816 | F/1 | 2009 Jan | Choking, flushing | Choking | No | No |

*ALTEs, acute life-threatening events; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HRV, human rhinovirus; EV, enterovirus; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

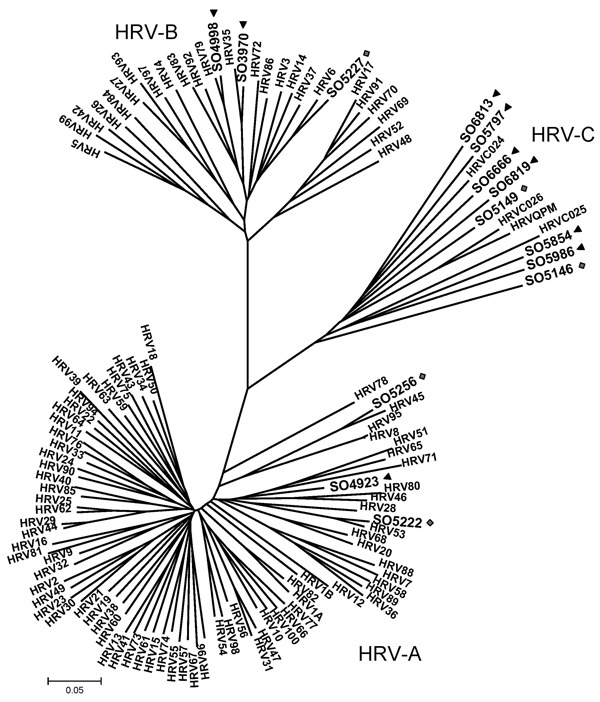

Phylogenetic analyses of 9 sequences obtained from patients showed distribution of HRV in 3 clusters. Three sequences were included in previously characterized clades, defined by HRV group A (HRV-A, SO4923–EU697826) and B (HRV-B, SO3970–FJ841954 and SO4998–EU697832). Sequence from patient SO4923 had a low sequence similarity with the other serotypes of HRV-A. In contrast, sequences from patients SO3970 and SO4998 were closely related to HRV-35 and HRV-79, respectively. Six sequences were included in the third group corresponding to the new HRV-C: SO5854, SO6666, SO5797, SO6819, SO5986, SO6813- FJ841955-57 and FJ841959-61) (3,10) (Figure). Different genotypes (collectively called HRV-Cs) were identified in 6 NPA specimens from children with ALTEs (67% of total HRV). Two received cardiopulmonary resuscitation at home; for these 2 patients, a respiratory syncytial virus and an HRV-C were identified. All 16 children survived.

Figure.

Phylogenetic analysis of 5′ noncoding region and viral protein (VP) 4/2 coding region of 9 human rhinoviruses (HRVs) identified in infants with apparently life-threatening events in Spain, November 2004–December 2008. Phylogeny of nucleotide sequences (≈492 bp) was reconstructed with neighbor-joining analysis by applying a Jukes-Cantor model; scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. Included for reference are sequences belonging to the novel genotype reported previously (QPM and 024, 025, 026 [11]) and all HRV-A and -B serotypes available in GenBank. Significant bootstrapping is indicated.

Conclusions

The most common discharge diagnoses reported for ALTEs are gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), unknown causes, seizures, and lower respiratory tract infections (11). Our series suggests that ALTEs of previously unknown etiology could be related to HRV infections. Rhinovirus infections are known to be a major cause of illness and hospital admission for young children, particularly infants <2 years of age (12). Detection of viral genomes by nested RT-PCR in NPA specimens led us to analyze the effect of HRV infections in different clinical situations. Respiratory infections associated with HRV might play a major role in young infants, probably with few clinical signs, and might contribute to apnea as a first manifestation. GERD is the most frequent hospital discharge diagnosis in published series (5,11). For our patients, GERD also was the most frequent clinical diagnosis (9 patients), but for 7 of them, a respiratory virus was identified. We cannot conclude whether GERD is a risk factor for apnea or whether signs are so nonspecific that diagnoses could be confused.

Alternatively, the new HRV-C group could account for as many as a quarter or even half of HRV infections (4,13). In children, it has been associated with bronchiolitis, wheezing, and asthma exacerbations severe enough to require hospitalization; the percentage of these children with hypoxia was substantial (13). In a case–control study, Khetsuriani et al. (4) found HRV-C only in case-patients, supporting the pathogenic role of this genogroup. They considered that HRV-C infections could be associated with more severe clinical manifestations than infections with other HRV genogroups A and B. These data could also support the role of HRV-C in infants with ALTEs found in this work.

Although we had no control group for our patients, we recently published a study of a cohort of 316 newborns up to 6 months of age tested weekly for respiratory diseases (mainly upper respiratory tract infections), coincident in age and time with our patients (14). HRV was present in 5 (3.6%) of 72 infants tested. Two viruses were genetically identified as HRV-C, demonstrating they form distinct genetic clusters, and no genetic similarity was obtained with the ALTE–related HRV-C viruses. In addition, a second group of asymptomatic children of different ages but in coincident epidemic seasons was studied. The group of children with HRV was substantially smaller than the group of children with respiratory disease (15).

Viral infections could play a major role in ALTEs. Rhinoviruses, especially HRV-C, could cause a respiratory infection with few symptoms in young infants and could trigger ALTEs in this age group. Therefore, HRVs and posterior genotyping should be included in studies of the etiology of ALTEs to help identify the true relevance of HRV-C infection to these episodes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lola Lopez-Valero, Nieves Cruz, Monica Sánchez, and Ana Calderón for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant PI060532 by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Institute of Health Carlos III. Research on viral respiratory infections is carried out in collaboration with the Influenza and Respiratory Viruses Laboratory at the National Center of Microbiology (ISCIII) and supported by the Health Research Fund.

Biography

Dr Calvo is chief clinician of pediatrics at Hospital Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madrid, Spain. Her research interests include infectious diseases in children.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Calvo C, García ML, Pozo F, Reyes N, Pérez-Breña P, Casas I. Role of rhinovirus C in apparently life-threatening events in infants, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Sep [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/9/1506.htm

References

- 1.Kusel MMH, Klerk NH, Holt PG, Kebadze T, Johnston SL, Sly P. Role of respiratory viruses in upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life. A birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:680–6. 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemanske RF Jr, Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, Li Z, Shult PA, et al. Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:571–7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamson D, Renwick N, Kapoor V, Liu Z, Palacios G, Ju J, et al. MassTag polymerase-chain-reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004–2005. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1398–402. 10.1086/508551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khetsuriani N, Lu X, Teague WG, Kazerouni N, Aderson LJ, Erdman DD. Novel human rhinoviruses and exacerbation of asthma in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1793–6. 10.3201/eid1411.080386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonkowsky JL, Guenther E, Filloux FM, Srivastava R. Death, child abuse and adverse neurological outcome of infants after apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2008;122:125–31. 10.1542/peds.2007-3376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Infantile Apnea and Home Monitoring, Sep 29 to Oct 1, 1986. Pediatrics. 1987;79:292–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pozo F, García-García ML, Calvo C, Cuesta I, Pérez-Breña P, Casas I. High incidence of human bocavirus infection in children in Spain. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:224–8. 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coiras MT, Aguilar JC, Garcia ML, Casas I, Perez-Brena P. Simultaneous detection of fourteen respiratory viruses in clinical specimens by two multiplex reverse transcription nested-PCR assays. J Med Virol. 2004;72:484-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.López-Huertas MR, Casas I, Acosta-Herrera B, Garcia ML, Coiras MT, Pérez-Breña P. Two RT-PCR based assays to detect human metapneumovirus in nasopharyngeal aspirates. J Virol Methods. 2005;129:1–7. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briese T, Renwick N, van den Berg M, Jarman R, Ghosh D, Köndgen S, et al. Role of rhinovirus in hospitalized infants with respiratory tract infections in Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:944–7. 10.3201/eid1406.080271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern MC, Smith MB. Causes of apparent life threatening events in infants: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1043–8. 10.1136/adc.2003.031740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo C, García-García ML, Blanco C, Pozo F, Casas I, Perez-Breña P. Rhole of rhinovirus in hospitalized infants with respiratory tract disease in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:904–8. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller EK, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Griffin MR, Hall CB, et al. A novel group of rhinoviruses is associated with asthma hospitalizations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:105–6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueno Campaña M, Calvo Rey C, Vázquez Alvarez MC, Parra Cuadrado E, Molina Amores A, Rodrigo García G, et al. Infecciones virales de vías respiratorias en los primeros 6 meses de vida. An Pediatr (Barc). 2008;69:400–5. 10.1157/13127993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-García ML, Calvo C, Pozo F, Pérez-Breña P, Quevedo S, Bracamonte T, et al. Human bocavirus detection in nasopharyngeal aspirates of children without clinical symptoms of respiratory infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:358–60. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181626d2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]