Abstract

Objectives. We examined the determinants of mental health, as perceived by bisexual people, in order to begin understanding the disparities in the rates of mental health problems reported by bisexual people versus those reported by heterosexual people, and, in many studies, gay men and lesbians.

Methods. Our community-based participatory action research project comprised focus groups and semistructured interviews with 55 bisexual people across the province of Ontario, Canada.

Results. Perceived determinants of emotional well-being identified by participants could be classified as macrolevel (social structure), mesolevel (interpersonal), or microlevel (individual). In the context of this framework, monosexism and biphobia were perceived to exert a broad-reaching impact on participants' mental health.

Conclusions. Like other marginalized populations, bisexual people perceive experiences of discrimination as important determinants of mental health problems. Additional research is required to examine the relationships between these perceived determinants of emotional well-being and specific mental health outcomes and to guide interventions, advocacy, and support for bisexual people.

A growing body of epidemiological evidence shows that sexual minorities, including gay men, lesbians, and bisexual people, report poorer physical and mental health outcomes than do heterosexuals.1–5 Experiences of discrimination—that is, exposure to unpredictable, episodic, or daily stress resulting from the social stigmatization of one's identity6—are important contributors to health disparities associated with minority sexual orientations.6,7

The health status of bisexual people has received little independent study, in part because the small sample sizes in many studies have led researchers to group bisexual people with gay men and lesbians.6,8 However, in studies that have examined bisexual people separately, they report poorer mental health and higher rates of mental health service utilization than do heterosexuals1,9–14 and, in some studies, than do lesbians and gay men.10–14

Various factors have been proposed to explain the association of bisexuality with these poor mental health outcomes, including the relative invisibility of bisexual people and a resulting lack of in-group community support.13 The specific discrimination experiences of bisexual people may also be important contributors to these mental health disparities. Bisexual people can experience biphobia, which is analogous to homophobia in that it describes negativity, prejudice, or discrimination against bisexual people. Similarly, monosexism is analogous to heterosexism: some people view only single-gender sexual orientations (heterosexuality and homosexuality) to be legitimate, and at the structural level, bisexuality is dismissed or disallowed.15 Finally, bisexual people may also experience internalized oppression7 in the form of internalized biphobia and internalized monosexism. These terms refer to an unconscious acceptance by bisexual people of negative or inaccurate social messages about bisexuality, potentially leading to identity conflict and self-esteem difficulties.

To our knowledge, no research to date has examined the relationships between these or other factors and mental health or emotional well-being as perceived by bisexual people. We therefore conducted a community-based participatory action research project to answer the following question: what factors, both positive and negative, do bisexual people perceive to be significantly associated with their mental health? Our goal was to draw upon the principles of grounded theory methodology to develop a conceptual framework to describe the perceived determinants of mental health for bisexual people in Ontario. We used participants' own qualitative descriptions of the factors that they perceived to affect their mental health to develop a framework that would enable us to begin to understand mental health disparities associated with bisexual identity.

METHODS

Research on mental health in sexual minority communities must be sensitively approached because historically their sexual orientations were treated by mental health professions, particularly psychiatry, as pathological.16 To address this challenge, we designed a community-based participatory action research project17,18 in which members of the bisexual community, representatives of partner organizations, and academic researchers were equally involved in every aspect of the research process.17 We developed the project in partnership with the Sherbourne Health Centre, Toronto, Canada, which serves sexual minority communities, and we hired bisexual community educators and activists as research staff.

Data Collection

We conducted 8 focus groups of 3 to 9 participants each and interviewed 9 additional participants who either lived in more remote settings or could not be included in focus groups for other reasons. Six focus groups met in Toronto: 2 with women, 3 with men, and 1 with transgender and transsexual people. A mixed-gender focus group convened in Ottawa, Canada's capital city (eastern Ontario), and another in a small community in southwestern Ontario. We interviewed 7 individuals by telephone and 2 at locations requested by the participants. Data collection began in December 2006 and was completed in October 2007.

We used the same semistructured guide for both interviews and focus groups. Our analysis focused on answers to the following questions:

What are some of the unique issues, experiences, and challenges you face as a bisexual person (or a person who is attracted to or sexually active with men and women)?

What are the main issues, experiences, and concerns you have faced over the course of your life as a bisexual person?

What do you feel has a positive impact on your mental health and emotional well-being as a bisexual person?

What do you feel has a negative impact on your mental health and emotional well-being as a bisexual person?

Prior to the focus group or interview, each participant provided written informed consent and completed a demographic questionnaire. Focus groups lasted approximately 2 hours and interviews 1 hour. At the close of each focus group or interview, participants received a package of resources on bisexual health.

Participants

Participants were identified through convenience sampling of community health and social service agencies; local bisexual or lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender organizations; online support and discussion groups; and advertisements in local newspapers. We advertised the study as “a community-based research project to better understand the factors that affect mental health and emotional well-being among bisexual people” and invited individuals who identified as bisexual or were attracted to or sexually active with both men and women to participate.

A total of 125 people expressed interest in the study. Of these, more than 40% reported learning about the study via e-mail or an online discussion group. Eligibility criteria, ascertained by a brief screening questionnaire completed by 99 (79%) of those who contacted us, included being aged 16 years or older, residence in Ontario, and self-identification as bisexual or as attracted to or sexually active with both men and women. Of those screened, 10 (10%) were ineligible: 9 participants lived outside of Ontario, and 1 did not meet our definition of bisexual.

We used purposive sampling to identify a final sample of 55 participants with diversity in gender, ethnicity, and geographic location. Selected demographic characteristics of participants are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Selected Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 55) in Study of Bisexuals and Mental Health: Ontario, Canada, 2006–2007

| Characteristics | No. (%) or Mean (Range) | |

| Gender identificationa | ||

| Male | 30 (55) | |

| Female | 25 (45) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Bisexualb | 41 (75) | |

| Queer | 8 (15) | |

| Omnisexual | 1 (2) | |

| No identity label | 5 (9) | |

| Ethnocultural background | ||

| White/Caucasian | 38 (69) | |

| Person of color | 17 (31) | |

| Relationship statusc | ||

| Single | 18 (33) | |

| Married/common law/living with partner | 16 (29) | |

| Partnered/dating | 18 (33) | |

| Divorced/separated | 14 (25) | |

| Multiple partners | 4 (7) | |

| Geographic location | ||

| Greater Toronto area | 30 (55) | |

| Ottawa area | 10 (18) | |

| Southwestern Ontario | 9 (16) | |

| Northern Ontario | 6 (11) | |

| Education | ||

| Completed college/university | 36 (65) | |

| Completed high school | 17 (31) | |

| Did not complete high school | 2 (4) | |

| Individual income,d $ | ||

| < 10 000 | 6 (11) | |

| 10 000–29 999 | 25 (45) | |

| 30 000–59 999 | 13 (24) | |

| 60 000–100 000 | 10 (18) | |

| > 100 000 | 1 (2) | |

| Age, y | 35 (18–66) | |

| Mental health historye | ||

| Experience with mental health problem reported | 38 (69) | |

| No mental health problem reported | 17 (31) | |

Included 13 people (24%) who also identified as transgender, transsexual, or both.

Included people who identified as bisexual or bisexual in combination with another identity.

Participants could select more than 1 option.

Median individual income was $20 000–$29 999.

Most commonly reported problems were depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

Data Analysis

Focus groups and interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim. We analyzed anonymized transcripts with a grounded-theory approach; this method of qualitative data analysis derives a conceptual framework or theory from the data.19,20 We used QSR N6 software to generate reports from the coded transcripts for each of the primary categories and subcategories.21 We then applied selective coding procedures20 to these reports to identify the linkages between the primary categories and construct a conceptual framework to elucidate the relationships between these categories and mental health or emotional well-being.

We validated the framework at a community launch of the research findings in September 2008. No substantive changes to the framework were required following this validation with participants and other community members.

RESULTS

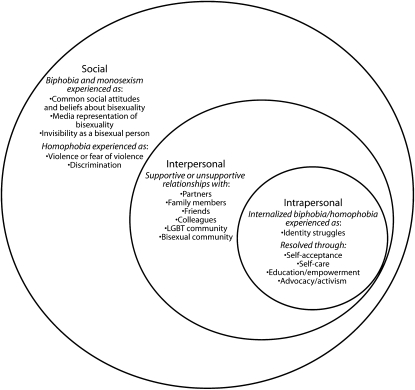

Our data indicated that the established sociological framework of intersecting macrolevel (social structure), mesolevel (interpersonal), and microlevel (individual) determinants of health22,23 agreed with our participants' descriptions of potential risk and protective factors for mental health problems (Figure 1). However, within this framework, specific factors at each level were unique to or operated in a unique context for bisexual people. Quotes that illustrate these factors are provided in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Potential risk and protective factors for mental health problems for participants in study of bisexuals and mental health: Toronto, Ontario, 2006–2007.

TABLE 2.

Quotations From Participants in Study of Bisexuals and Mental Health: Ontario, Canada, 2006–2007

| Factors Affecting Mental Health | Participant Comments |

| Macrolevel (social structure) | |

| Experiences of biphobia and monosexism | “I just don't tell anybody [that I'm bisexual], because I hear all the jokes … my age being as it is that I never felt comfortable actually telling anybody how I felt” (Rebecca, an older participant). |

| Common social attitudes and beliefs about bisexuality | “The stereotype is that bisexuals are confused, because they don't know who they are, and what I've actually realized is that society is confused, because they don't know who we are.” (Owen) |

| Media representation of bisexuality | “I think I've always feared being visible as a bisexual woman. Mainly because what's been portrayed to me in media or anywhere on the dance floor are girls who acted out to get male attention, and I was always afraid that people would think that that's what I'm doing.” (Kate) |

| Invisibility as a bisexual person | “I didn't even know bisexuality existed until I was in my early twenties… . It didn't occur to me that there was something other than straight or gay, that was what I was taught.” (Sharon) |

| Experiences of homophobia | “I was walking on Yonge Street [in Toronto] with my friend and some guys yelled out of a car, ‘you fuckin' faggots.’ We were doing nothing. We were walking on Yonge Street on the sidewalk, and, and we're not partners.” (Miguel) |

| Mesolevel (interpersonal) | |

| Partner and intimate relationships | “One of my first really serious relationships with a male, he was quite homophobic, and I told him about a past lover of mine who was female. And he was incredibly immature about it. And he would make fun of me … anyways, it was pretty traumatic, and it took me years to overcome, and fully step into who I really am.” (Donna) |

| Family members | “My father's from [an African country], and there people still kind of believe that homosexuality isn't even African at all. Like, it's like this thing that white men brought.” (Owen) |

| Friends | “I have 2 very close friends that also identify as bisexual and we are like this [crosses fingers]. Very tight, very close, they've been really supportive. They understand what I'm going through. They're very accepting. So I think that that has been extremely—I feel very lucky.” (Nicole) |

| Colleagues | “When I got a new boss, I contemplated for a long time whether I should say ‘Hey, I'm living with a woman’ and ‘I have bipolar disorder.’ Those are two sort of big bombs, I was trying to figure out which one to drop first. I felt, for me, in terms of taking care of my mental health, it was important to have been open about both.” (Diana) |

| LGBT community | “It's actually fun to feel part of the LGBT community. I think all 4 are very different, and it shouldn't necessarily always be lumped together, but at the same time it's fun to sort of say, I'm part of this community… . I see myself maybe wanting to become a bit of an advocate for all 4 [communities] and, like, that could be something I could feel proud of.” (Chris) |

| Bisexual community | “It was great for my mental health [to go to meetings of a bisexual support group] … just to sort of look around the room and go, oh my god, maybe I'm not as alone as I think I am.” (Diana) |

| Microlevel (individual) | |

| Struggles with identity | “My thought process was, at least if I was gay I have no choice, I have to find a woman to be with for the rest of my life. But in this society, I'm supposed to be with a man, but what if I fall in love with a woman? And it was just constant anxiety about that. Too many choices, you know?” (Leslie) |

| Self-acceptance | “I think the fact that I've been able to come to a position of peace and be a Christian and a bisexual and polyamorous all at the same time, and make those pieces of the puzzle fit together. I think that, that's been healthy for me.” (James) |

| Self-care | “There's a lot of things that have a positive impact on my health, things that have nothing to do with being a bi person. Things like exercise, and schoolwork, and socializing, finding a babysitter on occasion and getting out of the house.” (Robyn) |

| Empowerment and education | “I was maybe in my early teens when I began to have regular Internet access at home, and it gave me an opportunity to find other bisexual people, to learn about different sexual identities in general, and understand that I wasn't alone.” (Jane) |

| Advocacy and activism | “[Speaking to others about bisexuality] helped me immensely. Just being able to tell my story to other people was really beneficial, I think. Because after every lecture that I did, there was always a couple people in the group that come up and talk to me and say, ‘I've never heard a bisexual person speak before, that was really powerful.’” (Aaron) |

Note. LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

Macrolevel Factors

The critical roles of biphobia and monosexism in participants' mental health experiences were apparent in their responses. Bisexuality is often dismissed or disallowed at a structural level, to the extent that participants felt they were constantly required to justify or explain their sexual identity: “[Y]ou're either straight or you're gay/lesbian. [People] don't see that there are other possibilities” (James [All names used here have been changed.]). Bisexual identity was structurally disallowed for transgender and transsexual participants in particular, as in the example of gatekeepers to gender identity services: “The general stereotype is that if you're bisexual, you're probably not transsexual, you're just confused. And that if you really are a transsexual and you really are a woman, then you should only be attracted to men, otherwise this is all bullshit” (Chris).

Participants described the invisibility of their bisexuality and expressed frustration at being labeled with either a gay or heterosexual identity tied to the gender of their current partner. They noted the added burden of constantly or repeatedly disclosing their bisexual identity, by contrast with the experience of gay men and lesbians, whose sexual identity is implicit in the disclosure of the gender of a current or past partner. Similarly, participants who were in long-term, monogamous relationships felt that others questioned the legitimacy of their bisexual identities, because they were not presently sexually active with both men and women. Bisexuality's lack of social legitimacy, several participants reported, meant that they were unaware that bisexuality existed during their teenage years and young adulthood.

Bisexuality is also explicitly degraded or demeaned in commonly held beliefs and attitudes about bisexuality, particularly as they are perpetuated through the media: “People assume you're promiscuous. People assume you have threesomes. People assume a lot about being bisexual that, for me, none of it is true” (Evelyn). In addition to being portrayed as hypersexual, bisexuals are commonly understood to be gay or lesbian people who are confused about their sexual orientation or in transition to coming out as gay or lesbian. Some common social beliefs and attitudes about bisexual people are gender specific; for example, bisexual men are viewed as carriers of disease to the heterosexual population, and bisexual women are seen as willing objects of sexual pleasure for heterosexual men.

Participants also described experiences of homophobia, particularly from people who assumed them to be gay or lesbian. In a particularly striking account, a respondent described the homophobic violence she and her girlfriend experienced in their isolated northern Ontario community: “My girlfriend came down to see me, and she got beaten, almost to death, for being a bisexual” (Carol). In this instance, simply being visibly in a same-sex relationship resulted in an incident of homophobic violence; the actual sexual orientation of the victim was irrelevant to her attacker.

Common social beliefs and attitudes about bisexuality, as well as other manifestations of monosexism, biphobia, and homophobia experienced by participants, were perceived to affect emotional well-being in diverse ways. Of particular importance to participants was the effect of internalization of these social perceptions, both by important people in their lives (family, friends, partners, and potential partners) and by the participants themselves.

Mesolevel Factors

Although participants noted the beneficial effects of a supportive partner on their emotional well-being, they also provided examples of relationship problems associated with partners and potential partners internalizing common social beliefs about bisexuality.

“I had the unfortunate experience of going on a date with this lesbian … she was very anti-bisexual. She said, ‘You're sitting on the fence. Make a choice, either you're gay or straight’” (Shaiva).

Polyamory, which can be broadly understood as a relationship structure in which individuals may have more than 1 romantic or sexual relationship, conducted openly with the consent of all involved, was a myth for some of our participants and a reality for others. Although only 4 (7%) respondents reported having multiple partners at the time of the study, others indicated openness to multiple relationships in the future. Although some of these participants had embraced the integration of their bisexual and polyamorous identities, others noted challenges that polyamory introduced, particularly in the development and nurturing of long-term relationships. Still other participants were not interested in polyamorous relationships and preferred monogamy.

Participants similarly expressed both value and challenges associated with support from family members. Many participants spoke about the difficulties their family members had embracing a bisexual identity: “My sister said to me … I would prefer it if you were just my gay brother, and not this slutty person who just sleeps with everyone” (Jonathan). This challenge was multilayered for participants who identified with minority ethnoracial communities. Some of these participants perceived that within their communities, a bisexual identity was considered even more pathological or more incompatible with their ethnoracial identity than a lesbian or gay identity would be.

Supportive friends, and particularly bisexual-identified friends, were described as beneficial for mental health. However, some participants expressed challenges in disclosing their bisexual identity to heterosexual friends: “Female friends have found out after a while, and they're like, ‘oh my god, why didn't you tell me? Ooh, then I don't feel comfortable around you’” (Anne). Conversely, some participants described anxiety about disclosing their bisexual identity to gay and lesbian friends, out of concern that they would be seen to be no longer legitimate members of the lesbian and gay community. Participants also expressed anxiety about disclosing their bisexuality in the workplace, while at the same time noting the mental health benefits of being out at work.

Participants described complex relationships with the larger lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and transexual community. Although some described positive interactions, others reported experiences of biphobia associated with involvement in predominantly gay and lesbian events:

“I remember being at a party and having a really good time, and then a bunch of people started talking about someone who wasn't at the party, and why wasn't she there, and she had ‘turned straight’ and was dating a man” (Emily).

By contrast, participants consistently expressed the value of access to a community of other bisexual people, although there was variability in the extent to which this desire was realized; geographic location was an important factor. For some, participation in our focus groups offered their first opportunity to meet and share experiences with other bisexuals: “I have never been in a room full of this many bisexuals that I've known” (Leah). Level of involvement in a bisexual community was dependent on other identity variables as well, particularly ethnicity and age, because bisexual communities were perceived to be primarily available for Toronto-based, White, and young or middle-aged bisexual people.

Microlevel Factors

Many participants described past, and sometimes ongoing, struggles to understand and accept their bisexuality:

“I always knew I was attracted to both men and women, but coming from a small town you know you're supposed to hide those feelings … you want to fit into the norm of society” (Aaron).

Participants demonstrated significant awareness of the extent to which they had internalized common social attitudes and beliefs about bisexuality:

“How did I get this idea that it isn't okay to be who I am? … I look at my culture, I look at my parents, and I'm like, okay, I get it, you didn't give me a space to see that it was possible” (Sharon).

Some participants noted a close relationship between their mental health and their sexual identity struggles: “When I'm feeling kind of crazy, I think I'm a lesbian … when I'm feeling good, I kind of think I am a happy, normal, well-adjusted bisexual” (Stephanie).

Many participants described the very positive mental health effects of self-acceptance, including acceptance of their bisexual (and sometimes other) identities: “I've found that my biggest struggle over the years was accepting myself. And then once I did that, I feel a lot less weight on my shoulders” (Shaiva). Self-acceptance seemed to come with time and age for some participants; others achieved this with the help of supportive counselors or therapists, friends, and communities who were positive about bisexuality.

Many participants emphasized the importance of self-care activities, including exercise, spiritual involvement, healthy support networks, and arts activities, in maintaining their emotional well-being. Participants noted that these self-care activities were beneficial for all people but that for bisexual people they served the additional purpose of providing a focus outside of the challenges and struggles related to their bisexual identities, as well as being important sources of pride and self-esteem. Finally, many participants described feelings of self-fulfillment associated with involvement in advocacy, activism, and other activities intended to help other bisexuals achieve self-acceptance and to challenge biphobia and monosexism in society.

DISCUSSION

Our results illustrate the far-ranging mental health impact of biphobia and monosexism, in combination with homophobia and heterosexism, as perceived by bisexual people. Experiences of discrimination were perceived to affect mental health both directly (e.g., anxiety associated with fear of sexual orientation–based violence) and indirectly, through their effects on interpersonal relationships (e.g., distress associated with relationship problems) and on individuals' senses of self-worth and self-esteem.

Our conceptual framework is consistent with research that has examined the various ways that homophobia and heterosexism can influence the emotional well-being of gay and lesbian people, particularly as described by the Minority Stress Framework.7 Our data are consistent with this and other frameworks describing intersecting macro-, meso-, and microlevel determinants of health, lending credibility and transferability to our study. However, to our knowledge, ours is the first study to specifically examine the experiences of bisexual people, which can then be compared with previous research on the impact of discrimination on gay and lesbian people.7

We noted some unique experiences among bisexuals. For example, our participants described self-questioning of their bisexual identity, often in relation to a gay or lesbian identity—one that was perceived to be less stigmatized than a bisexual identity. That this questioning often occurred during times of mental health challenges demonstrates the strength required to continually resist social pressure to conform to a heterosexual–homosexual dichotomy.

It is seldom acknowledged that bisexual people experience homophobia and heterosexism in addition to biphobia and monosexism. Participants in our study described experiencing rejection both from the heterosexual community (often in the form of homophobia) and from the gay and lesbian community (often in the form of biphobia). Bisexual people may in fact experience more social discrimination than those who identify as gay or lesbian because of their doubly stigmatized identity. In addition, many bisexual people simultaneously negotiate other stigmatized identities (e.g., as people of color or as transgender and transexual people).24 The effect of multiple oppressions on the well-being of bisexual people requires further study, which may be informed by research examining the experiences of other doubly marginalized communities, such as biracial people.25,26

Our participants felt that the media and many social institutions failed to acknowledge bisexuality as a legitimate and healthy sexual identity. When the media and other information sources refer to bisexuality or bisexual people, they often perpetuate negative, hurtful, or inaccurate images. For example, although it is true that some bisexual people are polyamorous, this relationship structure is not more common among bisexuals than among heterosexual, gay, or lesbian people.27,28 Furthermore, research on polyamory among bisexual people has differentiated this practice from promiscuity, describing it instead as a form of responsible nonmonogamy.29

In the context of the perceived multilevel significance of structural factors on the mental health of bisexual people, meaningful improvements might be expected only once problems in the surrounding society have been addressed. This raises the question of how, from a public health perspective, the development of a more supportive social environment can be facilitated. Although addressing systemic discrimination is clearly a challenging undertaking, existing initiatives to address other forms of discrimination (including homophobia and heterosexism) could be expanded to address issues specific to bisexual people. For example, to address common beliefs about bisexuality (a macrolevel manifestation of biphobia and monosexism described by our participants), public health agencies could include healthy images of bisexuality in antidiscrimination public education campaigns.

Sexual health education presenting bisexuality as a legitimate and healthy identity would both address the invisibility of bisexuality (another macrolevel manifestation of biphobia and monosexism) and alleviate identity struggles at the intrapersonal level for bisexual youths. Support groups for partners of bisexual people could be established to deconstruct common social beliefs about bisexuality, particularly as they relate to bisexual people's capacity for healthy, stable relationships. This would not only address a manifestation of biphobia and monosexism at the structural level, but also address biphobia and monosexism experienced in the context of bisexual people's relationships with partners and potential partners—a perceived interpersonal determinant of mental health problems described by our participants.

Limitations

Because we conducted our study in 1 province of Canada, the extent to which our findings are reflective of the experiences of bisexual people in other settings is uncertain. Although Ontario is geographically diverse (it includes the largest city in Canada along with smaller towns and remote rural communities), a relatively progressive institutional environment exists throughout the province. However, we would expect that the negative effects of discrimination on emotional well-being would be even more pronounced in less supportive jurisdictions. That is, in settings where bisexual people experience even greater levels of discrimination, the negative mental health impact may be more significant than our participants described.

Our convenience recruitment method likely resulted in a sample of bisexual people who were predominantly open about and comfortable with their sexual orientation. Furthermore, in acknowledgment of the fluidity of sexual identities,30,31 we opted to use a broad definition of bisexuality that included self-identification, sexual behavior, and sexual attraction. Although the majority of our sample endorsed a bisexual identity, there may be differences between those who self-identify as bisexual and those who do not. Finally, the majority of our sample reported experience with a mental health problem. The extent to which our findings can be generalized to a broader sample of bisexual people is therefore unknown.

Conclusions

Our use of qualitative methods did not permit conclusions about causal relationships between the factors identified by our participants and mental health (and other health) outcomes. Our data suggesting an association between discrimination and mental health among bisexuals could serve as a starting point for future research. For example, quantitative studies could explore the relationships between these perceived determinants and mental health outcomes. Respondent-driven sampling, a novel strategy for sampling of hard-to-reach populations,32 might be of value in this research. Opinion polls could quantify social beliefs about bisexuality. Research is also needed to develop and test interventions and supports for bisexual people to ultimately improve the mental health status of this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Community Research Capacity Enhancement grant from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Lori E. Ross was supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Ontario Women's Health Council (NOW-84656). Support to CAMH for salary of scientists and infrastructure was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

We thank Anna Travers, Ayden Scheim, Loralee Gillis, and our participants for their essential contributions to this research.

Note. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

Human Participant Protection

This project was approved by the research ethics board of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Participants provided written consent.

References

- 1.Diamant AL, Wold C. Sexual orientation and variation in physical and mental health status among women. Journal Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12(1):41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandfort TG, Bakker F, Schellevis FG, Vanwesenbeeck I. Sexual orientation and mental and physical health status: findings from a Dutch population survey. Am J Public Health 2006;96(6):1119–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: results from the California Quality of Life Survey. Am J Public Health 2007;97(11):2048–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health 2007;97(6):1134–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King M, Semlyen J, See Tai S, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 2001;91(11):1869–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129(5):674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen DJ, Bradford JB, Powers D, et al. Comparing women of differing sexual orientations using population-based sampling. Women Health 2004;40(3):19–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNair R, Kavanagh A, Agius P, Tong B. The mental health status of young adult and mid-life non-heterosexual Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005;29(3):265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Mickey RM, Rothblum ED. Mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings: effects of gender, sexual orientation, and family. J Abnorm Psychol 2005;114(3):471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses' Health Study II. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13(9):1033–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koh AS, Ross LK. Mental health issues: a comparison of lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual women. J Homosex 2006;51(1):33–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Rodgers B, Jacomb PA, Christensen H. Sexual orientation and mental health: results from a community survey of young and middle-aged adults. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjepkema M. Health care use among gay, lesbian and bisexual Canadians. Health Rep 2008;19(1):53–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett K. Feminist bisexuality: a both/and option for an either/or world. : Weise ER, Closer to Home: Bisexuality and Feminism Seattle, WA: Seal Press; 1992:205–231 [Google Scholar]

- 16.King M. Dropping the diagnosis of homosexuality: did it change the lot of gays and lesbians in Britain? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003;37:684–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. : Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Community Based Participatory Research for Health San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003:53–76 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris M, Muzychka M. Participatory Research and Action: A Guide to Becoming a Researcher for Social Change Ottawa, Canada: CRIAW/ICREF; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cresswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedure and Techniques Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 21.QSR N6 [computer software] Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31(6):1091–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hertzman C, Power C, Matthews S, Manor O. Using an interactive framework of society and lifecourse to explain self-rated health in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med 2001;53(12):1575–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dworkin SH. Biracial, bicultural, bisexual: bisexuality and multiple identities. J Bisexuality 2002;2(4):93–107 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vivero VN, Jenkins SR. Existential hazards of the multicultural individual: defining and understanding ‘cultural homelessness.’ Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 1999;5:6–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman VH, Carter MM. Biracial self-identification: impact on trait anxiety, social anxiety and depression. Identity 2007;7(2):103–114 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumstein P, Schwartz P. American Couples New York, NY: William Morrow; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber A. Who are we? And other interesting impressions. Loving More 2002;30:4–6 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klesse C. Polyamory and its ‘others’: contesting the terms of non-monogamy. Sexualities 2006;9(5):565–583 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond LM. Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol 2008;44:5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl 1997;44(2):174–199 [Google Scholar]