Abstract

The current study evaluated the associations between externalizing psychopathology and marital adjustment in a combined sample of 1,805 married couples. We further considered the role of personality in these associations, as personality has been found to predict both the development of externalizing psychopathology as well as marital distress and instability. Diagnostic interviews assessed Conduct Disorder, adult symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder, and Alcohol Dependence. Personality was assessed using the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale was used to measure marital adjustment. Results indicate that more externalizing psychopathology, greater Negative Emotionality, and lower Communal Positive Emotionality were associated with reduced marital adjustment in both individuals and their spouses. Low Constraint was associated with reduced marital adjustment for individuals but not for their spouses. Multivariate analyses indicated externalizing psychopathology continued to predict marital adjustment even when accounting for overlap with personality. These results highlight the importance of examining the presence of externalizing psychopathology and the personality attributes of both members of a dyad when considering psychological predictors of marital adjustment.

Keywords: externalizing, psychopathology, personality, marital adjustment

Satisfying marriages are valued by nearly all adults in the United States (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 2005). Indeed, marital satisfaction is one of the largest correlates of life satisfaction according to a recent meta-analysis (average r = .42: Heller, Watson, & Ilies, 2004). Moreover, distressing romantic relationships are associated with poor physical health and diminished well-being (Bloom, Asher, & White, 1978; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Given these findings, there is considerable clinical interest in understanding the risk factors for relationship distress. The primary objective of the present study is to examine how externalizing spectrum psychopathology (i.e., substance use disorders and antisocial behavior; Krueger, Markon, Patrick, & Iacono, 2005) and personality traits are uniquely associated with marital adjustment in sample of over 1,800 married couples.

Theoretical Perspectives Linking Personal Attributes to Intimate Relationships

Theoretical approaches to relationships have been broadly distinguished as either intrapersonal or interpersonal (see Kelly & Conley, 1987). Intrapersonal approaches consider how individual differences in either personality or psychopathology are associated with relationship functioning whereas interpersonal approaches focus on how behavioral interactions between partners are associated with relationship quality and stability. Several integrative models have recognized that these are complementary perspectives, linking individual differences and interpersonal processes (e.g., Bradbury & Fincham, 1988; Caughlin, Huston, & Houts, 2000; Donnellan, Assad, Robins, & Conger, 2007; Huston & Houts, 1998; Karney & Bradbury, 1995). A common theme in these approaches is that individual differences in psychopathology and personality help to form the “psychological infrastructure” of marital relationships (e.g., Huston & Houts, 1998). One widely known theoretical model, the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) model, proposes that individual differences in personality and psychopathology create “enduring vulnerabilities” that affect how couples adapt to stressful experiences (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). This adaptation then impacts overall relationship satisfaction. In short, VSA predicts that individual differences in personality and psychopathology will be associated with couples’ perceptions of marital satisfaction.

Consistent with these models, research has implicated both psychopathology (e.g., depression) and personality (e.g., traits linked with emotional distress and interpersonal hostility) as important statistical predictors of relationship distress (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Gonzaga, Campos, & Bradbury, 2007; Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2000; Whisman, 2007). However, much of the existing literature in this area has focused primarily on internalizing psychopathology (i.e., depression and to a lesser extent anxiety), and it is therefore unclear whether externalizing psychopathology in both spouses is related to marital adjustment.

Externalizing Psychopathology and Marital Adjustment

One of the most commonly studied manifestations of externalizing psychopathology studied as it relates to romantic relationships is alcohol misuse (Marshal, 2003; Whisman, 2007). For example, Marshal (2003) reviewed 60 studies and found that problematic drinking was associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction, higher levels of maladaptive marital interaction patterns, and higher levels of marital violence. Heavy alcohol use thus appears to have deleterious consequences for relationships.

Although studied less frequently than alcohol-related disorders, psychopathology that manifests as aggression and interpersonal animosity has also been linked to marital distress (e.g., Andrews, Capaldi, Foster, & Hops, 2000; Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Lawrence & Bradbury, 2001). The best example of an extreme manifestation of these traits is found in Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), which is characterized by interpersonal hostility and a disregard for the rights of others. Savard, Sabourin, and Lussier (2006) found that sub-clinical symptoms of psychopathy (which overlaps with many of the symptoms of ASPD) in males were associated with decreases in marital quality for both men and women in a longitudinal analysis. However, Savard and colleagues (2006) failed to examine psychopathic personality attributes in women, and thus it is unknown whether gender moderates these statistical effects. Capaldi and Crosby (1997) examined both men and women in their study but they focused on younger adults and examined the narrower attribute of aggression. Indeed, we know of no study examining the range of symptoms for ASPD in both spouses, especially past young adulthood.

Most importantly, however, it remains unclear whether associations between externalizing psychopathology and marital adjustment exist independently beyond their overlap with personality. For example, alcohol-related disorders and ASPD consist of symptoms such as impulsivity that overlap with personality traits of self-control (e.g., Constraint). ASPD also contains aspects of interpersonal antagonism, attributes which overlap with Negative Emotionality (Krueger et al., 2005; Tellegen, 1982). Furthermore, at least one of these associations between psychopathology and personality traits extends to the etiologic level, such that common genes are responsible for the association between constraint and externalizing psychopathology (Krueger, Hicks, Patrick, Carlson, Iacono, & McGue, 2002). Given this, it may be that after accounting for the shared overlap with normal personality traits, externalizing psychopathology per se has little unique associations with the marital relationship.

Indeed, there is a considerable body of evidence linking “normal” personality attributes to marital distress. One of the most studied dimensions is the tendency to more readily experience aversive negative emotions (see e.g., Clark & Watson, 1999), a trait that is often labeled Negative Emotionality, Neuroticism, or Negative Affectivity (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Heller et al., 2004; Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Karney, Bradbury, Fincham, & Sullivan, 1994; Kelley & Conley, 1987; Robins et al., 2000; Watson, Hubbard, & Wiese, 2000). In particular, Negative Emotionality is associated with greater levels of dissatisfaction, instability, and even observed hostility in romantic relationships (see e.g., Donnellan, Conger, & Bryant, 2004; Pasch, Bradbury, & Davila, 1997).

Unfortunately, personality traits beyond Negative Emotionality have been largely overlooked. For instance, Karney and Bradbury (1995) noted that “whether other personality variables account for significant variance in marital outcomes after controlling for neuroticism remains to be examined” (p. 21). That said, there is some literature linking planfulness and self-control (i.e., Constraint) with more satisfying marriages (e.g., Heller et al., 2004; Robins et al., 2000). There are also hints that men’s Constraint is more strongly associated with relationship distress when compared to women’s Constraint (Robins et al., 2000). Moreover, traits related to the affiliative neurobiological system (see Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005) thought to underlie Agreeableness and aspects of Communal Positive Emotionality appear to be positively associated with relationship experiences (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Heller et al., 2004; Robins et al., 2000). Often these positive traits are examined in the form of marital processes such as partner support, which has been associated with marital functioning and health outcomes (see Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000 for a review). In other words, whereas Negative Emotionality and externalizing psychopathology may capture the “enduring vulnerabilities” in the VSA model, Communal Positive Emotionality and higher levels of Constraint may capture “enduring strengths” in the model. These strengths are equally important to consider, as they may serve as protective factors in the marital relationship. There is thus a need for studies that examine whether personality attributes beyond Negative Emotionality are associated with marital adjustment, and moreover, consider how these “enduring strengths” might also relate to the association between externalizing psychopathology and marital adjustment.

Additional Limitations in Previous Research

In addition to the theoretical gaps we highlighted above, the existing literature linking marital adjustment with externalizing psychopathology or personality traits is limited in a couple of other important, if more general, ways. First, research in this area is generally underpowered because most studies do not have large sample sizes (i.e., samples of 100 couples are common; see Karney & Bradbury, 1995). This is an especially noteworthy concern because Asendorpf (2002) pointed out that effect sizes for individual personality traits are often small when studying multiply determined outcomes like relationship satisfaction (see also Ahadi & Diener, 1989), which means that researchers need large sample sizes to reliably detect effects. Likewise, we also expect the effects for externalizing psychopathology to be relatively “small” by conventional standards. However, this does not mean that the “small” effects in question are inconsequential; recent research on the life course consequences of personality demonstrates how putatively “small” effects can have significant consequences for important life outcomes like longevity, criminality, and relationships (e.g., Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

Concerns about sample sizes are especially relevant when evaluating hypotheses linked with gender differences. Despite the often-discussed view that gender is a moderator of relationship effects, research on psychopathology and marital adjustment has been mixed with regard to gender differences. This could be a consequence of truly trivial gender differences or it could be a consequence of the presence of more subtle gender effects that do not consistently replicate across studies (e.g., Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003; Whisman, 2007). Accordingly, research using large samples to examine whether gender is a moderator is clearly needed. The current study is ideally suited in this regard, as analyses were based on a combined sample of over 1,800 couples.

Last, many studies do not rely on dyadic data analytic techniques for addressing questions about the associations between individual characteristics and marital satisfaction. In particular, the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) is the most appropriate technique for examining dyadic questions because it models the interdependence that is inherent in couple data and provides separate estimates for both “actor” and “partner” effects. Actor effects capture the strength of the association between an individual’s own characteristics and his or her own marital adjustment. Partner effects, by contrast, capture the cross-spouse effect, or the association between the individual’s characteristics and the relationship distress of his or her partner. As partner effects are measured over and above those of the actor effects, they would provide compelling evidence that individual differences in psychopathology and personality have interpersonal correlates.

The Current Study

The current study uses the APIM in a large sample of long-term married couples to evaluate the association between marital adjustment and individual differences in externalizing psychopathology while also evaluating and controlling for its association with personality. We specifically expected externalizing psychopathology to be associated with lower perceptions of marital adjustment. We further predicted that the personality trait of Negative Emotionality would be negatively associated with marital adjustment whereas Communal Positive Emotionality would be positively associated with marital adjustment. Finally, we explored whether externalizing psychopathology was independently associated with marital adjustment after controlling for personality (i.e., do effects persist when controlling for the statistical association between the predictors?). All in all, the present study offers an important opportunity to replicate and extend the existing literature using one of the largest samples of established couples to date.

Method

Participants

The total sample in the present study consisted of 1,805 established married couples with children from Minnesota where both parents participated in the assessment (total N=3,610 participants). Participants ranged in age from 29-66 years, averaging 42.9 for wives (SD = 5.3) and 44.9 for husbands (SD = 5.7). Couples had been married for an average of 19.6 years (SD = 5.6), with a range of 1 to 39 years (only 5% had been married less than 10 years, and 22% had been married less than 15 years). Participants were predominantly Caucasian (95-98%), and were therefore generally representative of the population of their home state. Nearly 84% of couples were the rearing parents of adolescent children (i.e., they had jointly parented their biological and/or adoptive children since infancy). The remainder were step-parents.

The majority of couples examined here (65%) came from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS). The MTFS is an epidemiologically-based, longitudinal study of same-sex twins and their parents. Two age cohorts of twins (ages 11 and 17 at their intake assessment) and their parents were recruited through Minnesota birth records and then located using public databases. In addition to the population-based participants, the MTFS also contains a “high-risk enrichment” sample (ES) (comprising 8% of the current study). The selection criteria for the ES were established prior to the on-site family assessment through a diagnostic interview during an initial phone screen. During the phone screen, the twins’ mother was administered portions of the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Conduct Disorder interviews from the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (Reich, 2000) in regard to her twins’ behaviors. If either twin showed more than the usual amount of externalizing psychopathology (i.e., a score of 5 or more on the screening questions), the family was invited to participate in the study.

Finally, we included parents from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS; 27% of the current sample). The SIBS is a population-based, longitudinal study of adoptive and non-adoptive adolescent siblings and their parents. Adoptive families living in the Twin Cities greater metropolitan area were contacted based on records of the three largest, private adoption agencies in Minnesota (averaging between 600 and 700 placements a year). Families were selected to have an adopted adolescent placed as an infant and first assessed between the ages of 11 and 19 years, and a second non-biologically related adolescent sibling falling within the same approximate age range. Non-adoptive families were randomly identified and recruited using public databases of Minnesota birth records. Although biological siblings were selected to have gender and age composition similar to that of the adopted siblings, biological and adoptive families were not otherwise matched.

Families were excluded from the any of three aforementioned studies if either twin had a cognitive or physical handicap that would preclude completion of the day-long, in-person assessment, or if the family lived more than one day’s drive from the Minneapolis laboratory. Of eligible families in the MTFS and ES, 83% agreed to participate, whereas 63% of adoptive and 57% of biological families from the SIBS sample participated. Compared to non-participating parents, participating parents of the MTFS and ES had slightly more years of education (0.25 years). However, they did not differ on socioeconomic status or self-reported mental health problems (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999). For the SIBS sample, there were no significant differences between participating and non-participating adoptive families in parental education, occupational status, and marital dissolution (McGue et al., 2007). Among biological parents, there were no significant differences between participating and non-participating families in terms of paternal education, paternal and maternal occupational status, or rate of divorce. However, participating mothers were more likely to have a college degree (44%) than were non-participating mothers (29%).

Measures

Marital Adjustment

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) was used to assess marital adjustment in all three subsamples. Of the 3,610 participants across all subsamples, only 77 (2%) were missing data on marital adjustment. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale is a 32-item scale assessing four aspects of marital adjustment: marital satisfaction, consensus, cohesion, and affective expression. We examined the overall scale, as it provides an overall measurement of dyadic adjustment that has been found to show stronger associations with other variables than the individual subscales (Graham, Liu, & Jeziorski, 2006). Total Dyadic Adjustment Scale scores evidenced good internal consistency reliabilities for men and women across all samples (α = .71-.84). In addition to the original 32 items, two items were added to our Dyadic Adjustment Scale measure to assess the extent of agreement between spouses regarding their parenting: how to raise the children and how to discipline the children. These questions were added because conflicts over child rearing seem to play a role in perceptions of marital adjustment for couples with children (e.g., Cui & Donnellan, 2009; Ishii-Kuntz & Seccombe, 1989; Kurdek, 1999). Reliabilities for these two items alone were excellent (α = .89-.90).

Clinical Assessment

During intake visits for all subsamples, trained bachelor-level and master-level interviewers assessed each parent for lifetime psychopathology using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-R; Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon, 1987). As DSM-III-R was the current manual at the onset of our twin assessments, we made use of DSM-III-R criteria for all participants in order to maintain continuity across samples. To reduce shared method variance, spouses were always assessed by different interviewers. Analyses in the current study centered on lifetime symptom counts of the following disorders: Conduct Disorder (symptoms present before age 16), Adult Antisocial Behavior (adult symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder, present at age 16 or later), and Alcohol Dependence.1 Of the 3,610 participants, only 26 (<1%) were missing data for Conduct Disorder, 26 (<1%) for Adult Antisocial Behavior, and 28 (<1%) for Alcohol Dependence.

Prior to the assignment of mental disorder symptoms, a clinical case conference was completed in which the evidence for every symptom was discussed by at least two advanced clinical psychology graduate students. To achieve consensus, audio tapes from the interview were replayed or the participant was re-contacted for clarification as necessary. For each symptom, the severity and frequency of the behavior were evaluated. Only symptoms that were judged to be clinically significant in both severity and frequency were considered present. The reliability of the consensus process was quite good, with kappas greater than 0.80 for diagnoses of all disorders. After symptoms were assigned, computer algorithms were used to create symptom counts corresponding to the criteria for DSM-III-R. Criteria were included in the symptom count only if they referred to symptoms of the disorders per se (i.e., symptom duration and hierarchical exclusionary rules were not included), although age of onset information was included (i.e., only Conduct Disorder symptoms present prior to age 16 were included).

In order to determine the percentage of individuals that met diagnostic criteria (according to the DSM-III-R) for each disorder, we used raw symptom counts without any exclusionary criteria. For Conduct Disorder, 40 (2%) women and 252 (14%) men reported 3 or more symptoms prior to adulthood (the number necessary for a DSM-III-R diagnosis). For Adult Antisocial Behavior (i.e., the adult symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder), 49 (3%) women and 283 (16%) men reported 3 or more symptoms. Finally, for Alcohol Dependence, 126 (7%) women and 514 (29%) men reported 3 or more symptoms. In order to capture an overall dimension of externalizing psychopathology, we summed the standardized scores of all three individual disorders to form a general externalizing disorder composite score (10% of women and 40% of men met criteria for at least one of the three disorders).

Personality

A 198-item version of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen, 1982) was used to assess personality in all subsamples. The MPQ is comprised of 10 primary scales that coalesce into three higher-order factors: Positive Emotionality (the dispositional tendency to experience positive affect/emotions), Negative Emotionality (the dispositional tendency to experience negative affect/emotions), and Constraint (high self-control and behavioral restraint). The Positive Emotionality primary scales include Well-being (e.g., optimistic, happy disposition), Social Potency (e.g., likes being in charge), Achievement (e.g., ambitious, persistent), and Social Closeness (e.g., sociable, affectionate). The Negative Emotionality primary scales include Stress Reaction (e.g., unaccountable mood changes, easily upset), Aggression (e.g., physically violent), and Alienation (e.g., estrangement). Lastly, the Constraint scales include Control (e.g., cautious, plans ahead), Harm Avoidance (e.g., avoids risk), and Traditionalism (e.g., conventionality). As prior research has indicated that associations between Positive Emotionality and marital adjustment differ by Positive Emotionality sub-factors (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Robins et al., 2000), current analyses made use of the agentic (high scorers are ambitious, socially dominant, and express positive emotional responsiveness; includes the Achievement and Social Potency scales) and communal (high scorers have higher interpersonal connectedness and experience positive emotions from their close relationships; includes the Well-Being and Social Closeness scales) sub-factors within Positive Emotionality.

The MPQ shows good internal consistency within college and community samples with alphas ranging from .76-.90 for the eleven primary traits, and a 30-day test-retest reliability ranging from .82-.92 (Tellegen, 1982). In the current study, higher-order factor alphas ranged from .82 to .85. Of the 3,610 participants in the combined sample, 182 (5%) were missing data on Agentic Positive Emotionality, 182 (5%) on Communal Positive Emotionality, 245 (7%) on Negative Emotionality, and 245 (7%) on Constraint.

Data Analyses with Actor-Partner Interdependence Models

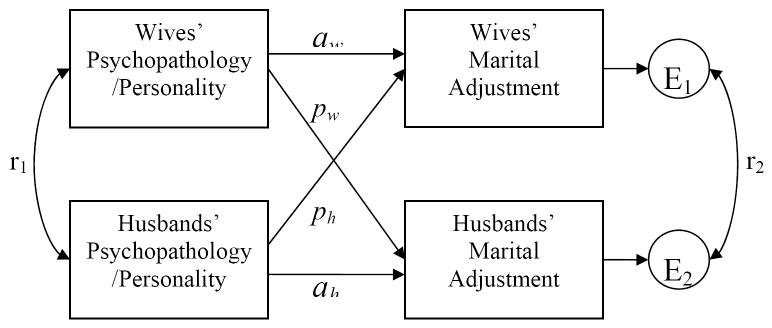

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; e.g., Kenny et al., 2006) was used to estimate the association between psychopathology/personality traits and marital adjustment (see Figure 1). As seen in Figure 1, actor effects are labeled aw and ah for wives’ and husbands’ actor paths, respectively. Partner effects for wives and husbands are labeled pw and ph, respectively. The model also provides explicit estimates of spousal similarity (r1) and spousal similarity on the residual variance within marital adjustment (r2).

Figure 1.

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006). aw and ah represent wives’ and husbands’ actor effects, respectively (i.e., the prediction of one’s marital adjustment from his/her own psychopathology/personality); pw and ph represent wives’ and husbands’ partner effects, respectively (i.e., the prediction of one’s marital adjustment from his/her spouse’s psychopathology/personality); E1 and E2 respectively represent the residual variance in wives’ and husbands’ marital adjustment, after controlling for a and p effects; r1 represents the association between spouses’ psychopathology/personality; r2 represents the residual association between spouses’ marital adjustment, after controlling for a and p effects.

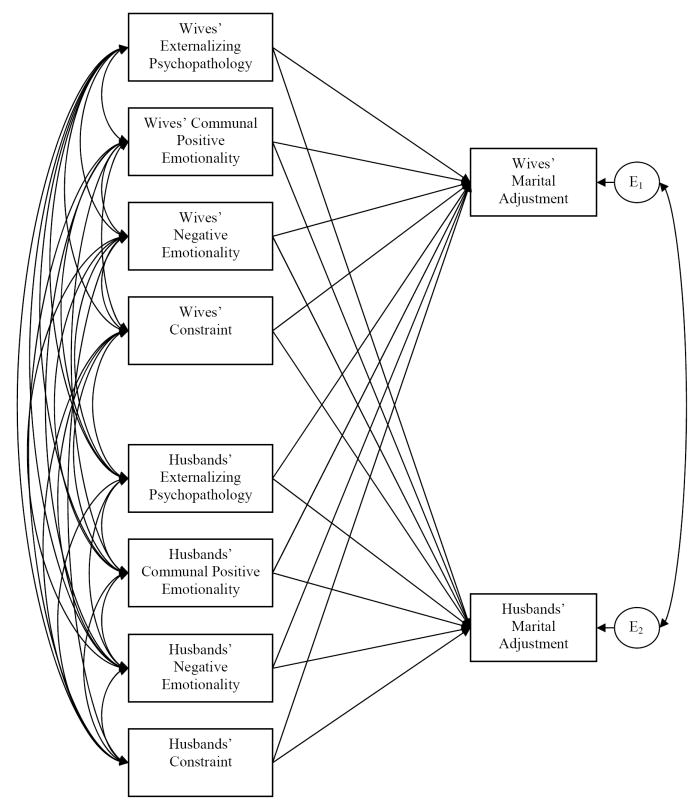

Analyses were first conducted separately for each predictor variable, so as to examine the “zero-order” actor and partner effect estimates. We then expanded the basic APIM to evaluate independent associations for externalizing psychopathology and personality when statistically predicting marital adjustment (see Figure 2). That is, we modified the basic model depicted in Figure 1 by simultaneously incorporating actor and partner effects for all personality attributes and externalizing psychopathology in the same analysis. In this way, we were able to examine, for example, the unique associations between externalizing psychopathology and marital adjustment, over and above any common associations with personality.

Figure 2.

A modified Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006). Paths from wives’ predictors to wives’ marital adjustment represent wives’ actor effects, and paths from husbands’ predictors to husbands’ marital adjustment represent husbands’ actor effects. Cross-spouse effects, meaning paths from wives’ predictors to husbands’ marital adjustment (and vice versa for husbands), represent partner effects. Path coefficients represent independent actor or partner effect because all predictors are estimated in the same model. E1 and E2 respectively represent the residual variance in wives’ and husbands’ marital adjustment, after controlling for actor and partner effects from all variables. Specific path estimates from this model are presented in Table 5.

All models were estimated using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Amos 7.0. In order to determine whether husbands and wives were statistically distinguishable within a dyad, we first tested for distinguishability by gender for each single variable analysis (following procedures described in Kenny et al., 2006). This test evaluated whether or not men and women were systematically different in terms of means, variances, and covariances for all variables included in Model 1. In these data, we found evidence for distinguishability for all sets of variables under consideration (χ2 values ranged from 40.5 to 936.1, df = 6, all ps < .05); however, an inspection of descriptive statistics indicated that mean-level differences were the primary source of gender differences.

Given that we were primarily concerned with whether gender moderated any of the associations in question and not the presence of mean-level gender differences, we imposed equality constraints on the basic APIM which specified that actor and partner effects were the same for husbands and wives. Accordingly, the fit of these models allowed us to empirically evaluate the reasonableness of the assumption that there were no gender differences in the size of actor and partner effects (see Kenny et al., 2006, p. 178). Model fit was adjudicated using the chi-square test of exact fit, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Given the concern that the chi-square test can lead to rejecting models that are trivially misspecified in large sample sizes (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), we followed the convention that reasonable models should have CFI values in excess of .95 and RMSEA values below .06 (see Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Sub-samples (i.e., MTFS, SIBS, and ES) were tested for significant differences prior to collapsing them into an overall, larger sample. Analyses demonstrated no substantial differences between the samples (this procedure is detailed below), and as such, descriptive statistics are presented for the overall sample. Means and standard deviations (as well as the proportion of the sample with enough symptoms for a “diagnosis”) are presented separately by gender (see Table 1). The fifth column contains overall gender effect sizes. As discussed above, these effect sizes indicate that there are significant mean gender differences for all forms of psychopathology, such that men reported higher mean levels of Conduct Disorder, Adult Antisocial Behavior, Alcohol Dependence, and the general Externalizing composite. Similarly, men reported higher means levels of Agentic Positive Emotionality and Negative Emotionality, although the effects for Negative Emotionality were very small (i.e., d less than ∣.20∣).2 Women reported higher levels of Communal Positive Emotionality, Constraint, and Dyadic Adjustment Scale scores, however the effect size for the difference in marital adjustment was trivial. The final column in Table 1 reports correlations between husbands and wives on all predictors (i.e., spousal similarity coefficients). The very high correlation for the Dyadic Adjustment Scale indicates that spouses agree to a considerable extent about the adjustment of their marriage.

Table 1.

Gender Comparisons For Marital Adjustment, Externalizing Disorder Symptom Counts, and Personality Scale Scores

| Variable (Scale Range) | Women | Men | Gender Differences Effect Size (d) (all p’s < .05) | Correlation Between Spouses (all p’s < .05) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Diagnostic Prevalence N (%) | Mean (SD) | Diagnostic Prevalence N (%) | |||

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale (61-204) | 158.8 (18.1) | NA | 157.7 (17.2) | NA | .06 | .63 |

| Conduct Disorder (0-9) | .32 (0.73) | 40 (2%) | 1.08 (1.38) | 252 (15%) | -1.04 | .09 |

| Adult Antisocial Behavior (0-7) | .73 (0.79) | 49 (3%) | 1.56 (1.12) | 283 (16%) | -1.05 | .22 |

| Alcohol Dependence (0-9) | .46 (1.24) | 126 (7%) | 1.71 (2.2) | 514 (29%) | -1.01 | .22 |

| Externalizing Composite (-2.95-9.5) | -1.17 (1.79) | 174 (10%) | 1.17 (2.28) | 721 (40%) | -1.31 | .33 |

| Agentic Positive Emotionality (44-140) | 90.5 (13.5) | NA | 95.4 (13.6) | NA | -.36 | .10 |

| Communal PEM (48-143) | 110.7 (13.8) | NA | 103.5 (13.7) | NA | .52 | .10 |

| Negative Emotionality (38-130) | 79.0 (12.6) | NA | 80.7 (13.2) | NA | -.13 | .21 |

| Constraint (75-195) | 151.4 (13.5) | NA | 144.1 (14.1) | NA | .54 | .20 |

Note. N represents number of individuals. NA represents Not Applicable. Descriptive statistics (aside from Diagnostic Prevalence rates) are based off of N=1,805 couples. Diagnostic Prevalence represents the proportions of the sample reporting three or more symptoms of each disorder according DSM-III-R criteria, and the Externalizing Composite represents the proportion of the sample meeting criteria for at least one disorder. Because the Externalizing composite was calculated by summing z-scores on the individual psychopathology variables (i.e., with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1.0), a mean negative value indicates that scores on the individual factors that made up the composite fell below the mean for those factors. Adult Antisocial Behavior diagnosis was made using symptom count criteria for Antisocial Personality Disorder, for which three or more symptoms merit a diagnosis. Because exclusionary rules and duration requirements were omitted from our symptom count variables, rates are upper estimates of the possible prevalences of these disorders in our sample. Standardized effect sizes are presented for the comparison of variables between gender. All gender differences effect sizes are significant at the p < .05 level. Negative effect sizes indicate that men scored higher than women. Correlations Between Spouses represent the correlations between husbands and wives on each variable of interest.

Associations across all forms of externalizing psychopathology, the Externalizing composite, and the personality variables can be found in Table 2. As seen there, externalizing psychopathology is consistently and significantly associated with Negative Emotionality and Constraint for both wives and husbands. In addition, Communal Positive Emotionality is negatively associated with all forms of externalizing psychopathology for men but only with Alcohol Dependence for women. This table suggests there is some degree of overlap between externalizing disorders and the broad spectrum of personality traits.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Externalizing Psychopathology and Personality Variables

| Conduct Disorder | Adult Antisocial Behavior | Alcohol Dependence | EXT Composite | Agentic PEM | Communal PEM | Negative Emotionality | Constraint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct Disorder | --- | .35** | .36** | .66** | .04 | .02 | .07** | -.14** |

| Adult Antisocial Behavior | .43** | --- | .36** | .80** | .08** | .00 | .07** | -.19** |

| Alcohol Dependence | .23** | .49** | --- | .67** | .01 | -.09** | .13** | -.09** |

| Externalizing (EXT) Composite | .72** | .75** | .75** | --- | .08** | -.02 | .11** | -.21** |

| Agentic Positive Emotionality | .04 | .06** | -.03 | .03 | --- | .32** | .13** | .00 |

| Communal Positive Emotionality | -.05* | -.09** | -.09** | -.10** | .39** | --- | -.49** | -.04 |

| Negative Emotionality | .11** | .14** | .21** | .19** | .03 | -.48** | --- | .13** |

| Constraint | -.20** | -.25** | -.13** | -.25** | .04 | .05 | .05* | --- |

Note. All correlations are based off of N=1,805 couples. EXT represents Externalizing and PEM represents Positive Emotionality. Wives’ correlations are reported above the diagonal and husbands’ correlations are reported below the diagonal. * and ** indicate coefficients are statistically significant at p < .05 and p < .01, respectively.

Table 3 displays correlations between all predictor variables and marital adjustment for wives and husbands. Results highlight that correlations between the wives’ predictor variables and marital adjustment are significant in the expected directions with the exception of Agentic Positive Emotionality and Constraint. For husbands, correlations between their predictor variables and marital adjustment were uniformly significant in the expected directions. Finally, cross-spouse or partner correlations (i.e., wife’s predictors with husband’s marital adjustment and vice versa) were significant in the expected directions for most variables. Non-significant correlations were found for partner correlations for Constraint in both husbands and wives. The correlation between wives’ Alcohol Dependence and husband’s marital adjustment, and correlations of husbands’ Agentic Positive Emotionality and Constraint with wives’ marital adjustment were also non-significant.

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Predictors and Marital Adjustment for Wives and Husbands

| Wife Dyadic Adjustment Scale | Husband Dyadic Adjustment Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wife | Conduct Disorder | -.07** | -.03 |

| Adult Antisocial Behavior | -.11** | -.12** | |

| Alcohol Dependence | -.06* | -.05 | |

| Externalizing Composite | -.12** | -.11** | |

| Agentic Positive Emotionality | .04 | .05* | |

| Communal Positive Emotionality | .29** | .17** | |

| Negative Emotionality | -.25** | -.12** | |

| Constraint | .03 | .05* | |

| Husband | Conduct Disorder | -.05 | -.09** |

| Adult Antisocial Behavior | -.10** | -.18** | |

| Alcohol Dependence | -.12** | -.14** | |

| Externalizing Composite | -.12** | -.17** | |

| Agentic Positive Emotionality | .02 | .07** | |

| Communal Positive Emotionality | .16** | .31** | |

| Negative Emotionality | -.17** | -.26** | |

| Constraint | .04 | .12** | |

Note. N=1,805 couples. * and ** indicate coefficients are statistically significant at p < .05 and p < .01, respectively.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)

Raw scores for all variables were standardized across the combined sample. It is generally not advisable to standardize coefficients separately within gender when specifying the APIM; however, standardizing across the combined sample, as we did, preserves mean-level gender differences and ensures that each dyad member remains comparable (Kenny et al., 2006). This standardization approach facilitated the interpretation of the unstandardized coefficients as essentially standardized coefficients given the metrics of the variables.

We first evaluated whether APIM estimates varied across the three subsamples using stacked models. To do so, we fit two nested models for each set of variables (e.g., Adult Antisocial Behavior and Dyadic Adjustment Scale; Conduct Disorder and Dyadic Adjustment Scale; Negative Emotionality and Dyadic Adjustment Scale). In the first model, a and p paths were allowed to vary across each of the three subsamples (i.e., freely estimated). In the second model, a and p paths were constrained to be equal across subsamples. In both models, means, variances, and error variances were freely estimated. We then compared changes in CFI values across the two models in order to test whether subsample moderated actor and partner effects (CFI differences are not sensitive to sample size like chi-square difference tests). We adopted Cheung and Rensvold’s (2002) suggestion that the difference in CFI between models should not exceed .01 (see also Byrne & Stewart, 2006, p. 307). The CFI differences were uniformly small (Δ CFI ranged between 0 and .006). Given these results, we elected to simplify the remaining APIM analyses (and further augment our statistical power) by combining our subsamples into one dataset.

Univariate Results for Externalizing Psychopathology and Personality

The first set of analyses using the APIM (i.e., Figure 1) were used to determine “zero-order” coefficients for a and p paths for all variables (i.e., the association of marital adjustment with each predictor was evaluated in a separate model). As noted before, a and p paths were constrained to be equal across gender (i.e., gender was not specified as a moderator of actor or partner effects) whereas means and variances for wives and husbands were freely estimated. Fit statistics and path coefficients for this “constrained model” are reported in Table 4 for each predictor. The constrained model provided a reasonable fit to the data, as indicated by the CFI values ≥0.99 and RMSEA values <0.05 and several chi square values that were not statistically significant (χ2 were only significant for Adult Antisocial Behavior and Constraint).

Table 4.

Univariate Results: Individual APIM Results Predicting Relationship Adjustment

| Predictor | Fit Indices For Constrained Model | Path Estimates For Constrained Model | Path Estimates For Unconstrained Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 on 2 df (p-value) | CFI | RMSEA | a (aw= ah) | p (pw= ph) | aw | pw | ah | ph | |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.2 (.54) | 1 | 0 | -.08** | -.05* | -.10** | -.03 | -.08** | -.05* |

| Adult Antisocial Behavior | 7.1* (.03) | .995 | .037 | -.15** | -.10** | -.11** | -.10** | -.19** | -.10** |

| Alcohol Dependence | 2.9 (.23) | .999 | .016 | -.11** | -.08** | -.07 | -.03 | -.13** | -.10** |

| Externalizing Composite | .3 (.87) | 1 | 0 | -.07** | -.04** | -.06** | -.04** | -.07** | -.05** |

| Agentic Positive Emotionality | 3.4 (.19) | .998 | .019 | .06** | .03 | .04 | .04 | .07* | .02 |

| Communal Positive Emotionality | .02 (.99) | 1 | 0 | .30** | .15** | .30** | .15** | .30** | .14** |

| Negative Emotionality | 4.9 (.1) | .997 | .028 | -.24** | -.10** | -.25** | -.07** | -.24** | -.12** |

| Constraint | 8.9** (.01) | .993 | .044 | .08** | .03 | .03 | .02 | .12** | .04 |

Note: N=1,805 couples. APIM represents the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Path estimate and correlation column labels correspond to those presented in Figure 1. Models were first fit constraining actor (a) and partner (p) effects to be equal across husbands and wives (i.e., aw = ah; pw = ph; as seen in Figure 1). These models uniformly provided an excellent fit to the data, as indicated by the CFI values ≥0.99 and RMSEA values <0.05. However, we also fit the unconstrained or fully saturated model (i.e., a and p effects were allowed to vary across spouses), particularly for the few instances where the chi-square test was significant (another, albeit very conservative, indicator of model fit; Adult Antisocial Behavior, Alcohol Dependence, and Constraint) on 2 degrees of freedom (df). Standardized path coefficients are presented. * and ** indicate coefficients that are statistically significant at p < .05 and p < .01, respectively.

Estimates for the unconstrained model are also presented on the right-hand side of Table 4 for purposes of comparison. A close inspection of the a and p estimates for Adult Antisocial Behavior indicated that the actor effect for husbands was stronger than the actor effect for wives (although both were statistically significant). A similar pattern for the actor effects emerged for Constraint, such that that the actor effect for husbands was larger than the actor effect for wives, an effect which also did not reach statistical significance. In any case, these results suggest that gender may play some role in moderating actor and partner effects for Adult Antisocial Behavior and Constraint. As can be seen for most other “unconstrained” estimates, path coefficients were similar to those from the constrained model. For Alcohol Dependence, path coefficients were no longer significant when examining them separately for husbands and wives. However, as stated above, the constrained model was still a better fit for this variable.

All psychopathology variables were associated with marital adjustment in the expected direction, such that higher levels of externalizing psychopathology predicted lower levels of marital adjustment. In particular, higher levels of Conduct Disorder, Adult Antisocial Behavior, Alcohol Dependence, and the overall Externalizing composite predicted lower levels of husbands’ and wives’ own marital adjustment (i.e., actor effects) and their spouse’s marital adjustment (i.e., partner effects). That said, however, the effects were generally small in magnitude (ranging from -.05 to -.15).

The personality variables were also associated with marital adjustment in the expected directions. Higher levels of Agentic and Communal Positive Emotionality and lower levels of Negative Emotionality significantly predicted higher levels of husbands’ and wives’ own marital adjustment. Higher Communal Positive Emotionality and lower Negative Emotionality predicted higher levels of spousal marital adjustment, suggesting that personality traits have associations with marital adjustment as reported by partners, an effect that is not confounded by shared informant biases.

Multivariate Results for Externalizing Psychopathology and Personality

Due to conceptual and empirical overlap between the externalizing disorders and some personality traits (see Table 2), we next evaluated the independent effects of the predictors (e.g., the effects of externalizing psychopathology on marital adjustment after accounting for the effects of personality). We conducted a multivariate analysis using the expanded APIM (Figure 2) by simultaneously estimating separate actor and partner paths for each of the predictor variables so as to evaluate their independent associations with marital adjustment. Agentic PEM was not included given the previously reported null results. Similar to Model 1, actor and partner paths for both externalizing psychopathology and personality predictors were constrained to be equal across gender while means and variances were freely estimated.

Fit statistics and path coefficients of this model are reported in note for Table 5. We only report the results for the overall Externalizing composite given that the results for separate disorders followed the same overall pattern (a complete table with results for personality and all three individual disorders is available upon request). As can be seen, the model provided an excellent fit to the data with a chi square value that was not statistically significant. For readers interested in specific spousal effects, we also fit a fully saturated model (df = 0) in which actor and partner paths were allowed to vary across gender. These path estimates are presented in the last four columns of Table 5.

Table 5.

Multivariate Results: Predicting Relationship Adjustment from Externalizing Psychopathology and Relevant Personality Variables

| Predictors | Path Estimates for Constrained Model | Path Estimates for Unconstrained Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wives | Husbands | |||||

| a (aw= ah) | p (pw= ph) | a | p | a | p | |

| Externalizing Composite | -.04** | -.03** | -.04** | -.03* | -.04** | -.03* |

| Communal Positive Emotionality | .23** | .11** | .22** | .13** | .22** | .09** |

| Negative Emotionality | -.13** | -.04* | -.14** | -.01 | -.13** | -.07* |

| Constraint | .07** | .02 | .05* | .03 | .08** | 0 |

Note. N=1,805 couples. As can be seen in Figure 2, all predictor variables were placed into the same model. Estimates for each predictor variable thus quantify its unique associations with marital adjustment (when controlling for the other predictor variables). This model was first fit constraining actor (a) and partner (p) effects to be equal across husbands and wives (i.e., aw = ah; pw = ph; as seen in Figure 1) but different for each predictor variable. The constrained model provided an excellent fit to the data, with χ2 (8) = 10.9, CFI = .999, and RMSEA = .014. Path estimates from a fully unconstrained (i.e., saturated) model with degrees of freedom (df) = 0 are reported in the last four columns for comparison purposes. Standardized path coefficients are presented. * and ** indicate coefficients are statistically significant at p < .05 and p < .01, respectively.

As seen in Table 5, the major univariate results held in these multivariate analyses. That is, actor effects remained statistically significant for all individual personality variables. Moreover, partner effects were significant for personality predictors, with the exception of Constraint (an effect which was not significant in univariate analyses, either). The path estimates for the constrained model were very similar to the unconstrained model, suggesting that the actor effects for Constraint, for example, held even when considering gender. Most importantly, however, both the actor and partner effects of externalizing psychopathology were still detectable (if small), even when controlling for overlap with personality. In sum, such results indicate that externalizing psychopathology has a unique and statistically detectable association with marital adjustment.

Discussion

Motivated by theoretical approaches like Karney and Bradbury’s (1995) Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) Model, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the association between marital adjustment and individual differences in externalizing psychopathology over and above any shared association with normal personality traits in a large sample of married couples. Results were generally consistent with our hypotheses. Higher levels of Alcohol Dependence and antisocial behavior were associated with lower levels of marital adjustment for both partners. Low Negative Emotionality and high Communal Positive Emotionality were associated with higher levels of self-reported marital adjustment in both the individual and the spouse. Finally, psychopathology had independent associations with marital adjustment, even when adjusting for the overlap with personality. These findings provide further insight into the individual characteristics that act as both enduring vulnerabilities to (viz., externalizing symptoms and Negative Emotionality) and enduring strengths (viz., Communal Positive Emotionality) for happy and satisfying marital relationships.

In general, we found evidence that the presence of externalizing psychopathology in either partner is related to poorer marital adjustment for both members of the romantic dyad. Consistent with prior research, we found that higher levels of alcohol dependence (e.g., Marshal, 2003; Whisman, 2007) were associated with poorer marital adjustment. Importantly, the results also suggest that symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Conduct Disorder were negatively related with relationship adjustment. Existing research has extensively examined other Axis I disorders in relation to marital distress (e.g., major depression), but has less frequently examined the effects of externalizing behaviors in wives and husbands. Although there was evidence for slight gender differences in actor and partner effects for Adult Antisocial Behavior, the direction and overall magnitude of these effects were similar. Moreover, the results for the other disorders associated with externalizing psychopathology showed little indication of gender differences. Accordingly, we tentatively conclude that the bulk of the results suggest that all varieties of externalizing symptoms are negatively associated with relationships, regardless of gender. These results suggest that future studies should evaluate externalizing symptoms in both members of the dyad rather than assuming that symptoms of externalizing psychopathology are only relevant for men given the mean-level differences between women and men.

In addition, we replicated and extended previous work which indicates that variation in personality is associated with marital adjustment. Consistent with previous work (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Robins et al., 2000), the tendency to more readily experience aversive emotions such as anxiety, anger, and fear (i.e., Negative Emotionality) was associated with relationship adjustment both for the individual and for his or her spouse. A more novel contribution of the present study was evidence linking Communal Positive Emotionality to marital adjustment. Consistent with the findings from Donnellan and colleagues (2007), Communal Positive Emotionality had a stronger association with marital adjustment than Agentic Positive Emotionality (see also Robins et al., 2000). Thus, there is now replicable evidence in support of the utility of dividing Positive Emotionality into separate domains for relationship research given that traits related to social affiliation appear to be more statistically predictive of relationship adjustment than traits related to social dominance, ambition, and zest.

Constraint in husbands had detectable actor effects for predicting relationship adjustment, but no partner effects. This gender difference in the actor effects of Constraint on relationships was similar to the difference in actor effects observed by Robins and colleagues (2000). It was also similar in direction to the actor effect of Antisocial Personality Disorder. Thus, there is some evidence that Constraint matters more for men’s own perceptions of relationship adjustment when compared to women’s Constraint. Unfortunately, these data cannot rule out the possibility that the observed actor effects are artifacts of shared method biases given that these actor effects are based on reports of two different variables from the same person. Future multi-method work is needed to thoroughly rule-out this possibility. Nonetheless, if a shared method bias is the best explanation for actor effects, then the gender difference for Constraint raises an intriguing issue as to why such a “method effect” is apparently relevant for men but not women.

Finally, the current study found that univariate effects generally held in multivariate analyses; in other words, both personality and externalizing psychopathology have unique statistical effects on marital adjustment. Such results suggest that although personality may predict and even precede the development of relationships and mental illness, both personality and externalizing psychopathology seem to have independent associations with marital adjustment. It appears that there is utility in assessing both symptoms of externalizing psychopathology and personality attributes.

In sum, these results demonstrate the significance of examining externalizing psychopathology as well as personality traits outside of negative emotionality as potential enduring vulnerabilities or strengths for marital adjustment. Although the effect sizes for these variables were generally small, it is important to note that small effects can have substantial applied value, especially when considering multiply determined and important life outcomes like marital adjustment (see Roberts et al., 2007). For example, Roberts and colleagues (2007) describe that small effect sizes are important when they have practical significance, as they found that personality traits significantly predict consequential outcomes such as mortality, divorce, and occupational outcomes. Indeed, as we noted in the Introduction, the attainment of a happy and satisfying marital union is something that is vitally important to many individuals and linked moderately to general life satisfaction (i.e., Heller et al., 2004). Thus, we believe that small effect sizes are meaningful in this context (see also Robins et al., 2000).

Although the current study has several strengths, it also has its share of limitations. First, we only reported cross-sectional associations.3 As such, these data themselves are not informative about the causal priority of the variables in question. However, there is some longitudinal evidence linking individual differences similar to those investigated in the current report to relationship adjustment (e.g., Newman, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1997; Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2002). This body of work suggests that variation in psychopathology and personality are causally prior to relationship satisfaction. However, even in light of this research, we cannot conclude this causal link given we used cross-sectional data.

A second limitation concerns the use of lifetime (i.e., retrospective and current) reports for the assessment of externalizing disorders. Given that externalizing symptoms tend to peak in late adolescence, some research has suggested that there may be little validity in asking adults to recall these past behaviors. However, evidence for this proposition is somewhat mixed (for a review of both sides, see Brewin, Andrews, & Gotlib, 1993). For Conduct Disorder, for example, the symptoms are generally discrete, specific behaviors (e.g., deliberately engaging in fire setting, vandalism, theft) that should be salient enough to be easily recalled in adulthood. Furthermore, Elkins, Iacono, Doyle, and McGue (1997) found that father’s retrospective recall of Conduct Disorder was effective in predicting all outcomes that would be expected by the actual presence of Conduct Disorder (i.e., high Negative Emotionality, low Constraint, alcohol and substance dependence, etc.).

A third limitation is that although the current study examines the independent effects of psychopathology and personality in a multivariate model, the distinction between the two sets of constructs may be somewhat artificial as there is increasing interest in examining links between normal personality and psychopathology (e.g., Krueger & Tackett, 2003). To be sure, there is substantial overlap between both constructs and research has suggested that personality differences may form the basis to understanding expressions of psychopathology (e.g., Krueger et al., 1993).

A final limitation is that the present study consisted predominantly of European Americans that span a wide age-range in lengthy marriages with at least two teenage children. Thus, we cannot generalize these particular findings with confidence to those in other ethnic groups or in marriages of a shorter duration or marriages without children. However, Donnellan and colleagues (2007) and Robins and colleagues (2000) found similar personality associations between personality and relationship satisfaction in samples of young adult couples who had been together for less time. Moreover, there was no indication that age was a potential moderator of effects reported in this paper.4

All in all, our results lend credence to the importance of observing the psychological functioning of both partners in a couple for better understanding relationship adjustment. Consistent with the VSA model, our results suggest that externalizing psychopathology may act as an enduring vulnerability for marital adjustment. It is important to emphasize that these results suggest that externalizing psychopathology in both wives and husbands has intimate interpersonal consequences. Moreover, our findings suggest that personality characteristics matter when dealing with relationship distress. Though we are not familiar with interventions tailored to specific personality styles, the current results imply such work may be warranted (see also Moffitt, Robins, & Caspi, 2001).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by USPHS Grants # DA05147, AA09367, and AA11886, DA13240, and MH65137.

Footnotes

Although data on other substance use disorders was available, these disorders were not included in the current study because of their very low base rates in the current sample. Prevalences of these disorders ranged from 0.1-1.7% for Amphetamines, Cocaine, Hallucinogens, Inhalants, Opioids, Phencyclidine, and Sedative Dependence, 5.7% for Cannibus Dependence, and 29.8% for Nicotine Dependence. Nonetheless, in order to test a recent hypothesis that suggests there are no longer effects for Alcohol Dependence on marital adjustment when substance use disorders are controlled for (i.e., Feingold, Kerr, & Capaldi, 2008), we created two composite averages of these disorders (one with nicotine and one without) and tested them separately along with Alcohol Dependence in our APIM. The results demonstrated that there were still significant, unique associations of Alcohol Dependence with marital adjustment even after controlling for substance use disorders. Inconsistent with Feingold and colleagues’ (2008) findings, our data did not demonstrate that controlling for substance use disorders eliminated the association between alcohol dependence and marital adjustment. This may be due to our significantly larger sample size (Feingold et al., 2008 had a sample size of 150) and the fact that Feingold and colleagues (2008) only examined men.

The size and direction of the gender difference in Negative Emotionality may raise questions given the expectation that women should score substantially higher than men on this dimension of personality. However, these results are actually consistent with the existing literature which indicates very small gender differences in this broad dimension of personality. For example, three studies have reported gender differences for Negative Emotionality where the effect size was below ∣.20∣ for individuals in their mid 20s or older (Donnellan et al., 2007 reported d = .00 for participants in their late 20s; McGue, Bacon, & Lykken, 1993 reported d = .08 for participants at approximately 29.6 years of age; Robins et al., 2002 reported d = .12 for participants aged 26 years).

Longitudinal data for some variables was available for 345 couples (N=690; 19% of the original sample) at 6 years following their intake assessment. Personality data was not assessed at this time point, because personality was considered relatively stable in adulthood, and retrospective Conduct Disorder symptoms were also not re-assessed. In order to test longitudinal effects, we first standardized variables using identical procedures described in the current study. We then formed a new composite of Alcohol Dependence and Adult Antisocial Behavior at both time points (i.e., intake and 6 years later). We used this Externalizing composite and the Dyadic Adjustment Scale score for both spouses at Time 1 as predictors of the respective variables at Time 2 in a cross-lagged model. Overall, results demonstrated no evidence of any prospective longitudinal effects of psychopathology on marital adjustment (i.e., the Externalizing composite and individual disorders at Time 1 were not related to marital adjustment at Time 2) for either spouse perhaps because of the appreciable degree of stability in marital adjustment (see Cole, 2006 for a discussion of stability effects). Indeed, the stability of these variables across was fairly high (i.e., stability regression coefficients of 0.46 for Externalizing psychopathology and 0.63 for the Dyadic Adjustment Scale) that there was relatively little variance left to be explained by longitudinal, cross-spouse associations. Moreover, mean levels and variances of symptoms and marital adjustment scores also did not significantly differ across time. These results are preliminary given the sample size but seem consistent with the enduring dynamics model in that personality and psychopathology are not associated with changes in marital adjustment over time but instead exert relatively consistent influences throughout the relationship.

Given the wide age-range of individuals in the current sample (i.e., 29 to 66), we examined age as a potential moderator in our univariate APIM analyses. To facilitate the evaluation of continuous variable moderators, we chose to use a multilevel modeling approach as opposed to SEM. Importantly, zero-order univariate estimates did not vary when using multilevel modeling as opposed to SEM. We placed age of both spouses in our original APIM analyses, including all moderation variables (i.e., age wife*wife predictor, age wife*husband predictor, age husband*husband predictor, age husband*wife predictor). We found no indication that age moderated the effects in question.

References

- Ahadi S, Diener E. Multiple determinants and effect size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:398–406. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Capaldi D, Foster SL, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB. Personality effects on personal relationships over the life span. In: Vangelisti AL, Reiss HT, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Stability and change in relationships. New York: Cambridge Univeristy; 2002. pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonnett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL, Asher SJ, White SW. Marital distruption as a stressor: A review and analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1978;85:867–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. Individual difference variables in close relationships: A contextual model of marriage as an integrative framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:713–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:964–980. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. Psychopathology and early experience: A reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:82–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Stewart SM. The MACS approach to testing for multigroup invariance of a second-order structure: A walk through the process. Structural Equation Modeling. 2006;13:287–321. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Caughlin JP, Huston TL, Houts RM. How does personality matter in marriage? An examination of trait anxiety, interpersonal negativity, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:326–336. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RG. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Second Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Coping with longitudinal data in research on developmental psychopathology. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Donnellan MB. Trajectories of conflict over raising adolescent children and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2009;71:478–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Hall TW, Bradbury TN. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: Within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:557–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue R, Morrone-Strupinsky J. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:313–395. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Assad KK, Robins RW, Conger RD. Do negative interactions mediate the effects of negative emotionality, communal positive emotionality, and constraint on relationship satisfaction? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Conger RD, Bryant CM. The Big Five and enduring marriages. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:481–504. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, Iacono WG, Doyle AE, McGue M. Characteristics associated with the persistence of antisocial behavior: Results from recent longitudinal research. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Kerr DCR, Capaldi DM. Associations of substance use problems with intimate partner violence for at-risk men in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:429–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga GC, Campos B, Bradbury T. Similarity, convergence, and relationship satsifaction in dating and married couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:34–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Liu YJ, Jeziorski JL. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:701–717. [Google Scholar]

- Heller D, Watson D, Ilies R. The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: A critical examination. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:574–600. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Houts RM. The psychological infrastructure of courtship and marriage: The role of personality and compatibility in romantic relationship. In: Bradbury TN, editor. The developmental course of marital dysfunction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 114–151. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor JT, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development & Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii-Kuntz M, Seccombe K. The impact of children upon social support networks throughout the life course. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:777–790. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, Sullivan KT. The role of negative affectivity in the association between attributions and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:413–424. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Conley JJ. Personality and compatibility: A prospective analysis of marital stability and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:27–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: The Guildford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bullletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Tackett JL. Personality and psychopathology: Working towards the bigger picture. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;17:109–128. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.2.109.23986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. The nature and predictors of the trajectory of change in marital quality for husbands and wives over the first 10 years of marriage. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1283–1296. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:135–154. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Bacon S, Lykken D. Personality stability and change in early adulthood: A behavioral genetic analyses. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:96–109. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behavior Genetics. 2007;37:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Robins RW, Caspi A. A couples analysis of partner abuse with implications for abuse-prevention policy. Criminology & Public Policy. 2001;1:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Antecedents of adult interpersonal functioning: Effects of individual differences in age 3 temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:206–217. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer DJ, Benet-Martínez V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:401–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Bradbury TN, Davila J. Gender, negative affectivity, and observed social support behavior in marital interaction. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Reich W. Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socio-economic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Two personalities, one relationship: Both partners’ personality traits shape the quality of their relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. It’s not just who you’re with, it’s who you are: Personality and relationship experiences across multiple relationships. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:925–964. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savard C, Sabourin S, Lussier Y. Male sub-threshold psychopathic traits and couple distress. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:931–942. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structural clinical interview for DSM-III-R. Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Brief manual for the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. University of Minnesota; 1982. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Hubbard B, Wiese D. General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self- and partner-ratings. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:413–449. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital distress and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in a population-based national survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:638–643. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]