Abstract

Background

Little is known about whether educational gradients in smoking patterns can be explained by financial measures of socioeconomic status (SES) and/or personality traits.

Purpose

To assess whether the relationship of education to 1) never smoking and 2) having quit smoking would be confounded by financial measures of SES or by personality; whether lower Neuroticism and higher Conscientiousness would be associated with having abstained from or quit smoking; and whether education effects were modified by personality.

Method

Using data from the Midlife Development in the US national survey, 2429 individuals were classified as current (n= 695), former (n=999), or never (n=735) smokers. Multinomial logistic regressions study questions.

Results

Greater education was strongly associated with both never and former smoking, with no confounding by financial status and personality. Never smoking was associated with lower Openness and higher Conscientiousness, while have quit was associated with higher Neuroticism. Education interacted additively with Conscientiousness to increase and with Openness to decrease the probability of never smoking.

Conclusions

Education and personality should be considered unconfounded smoking risks in epidemiologic and clinical studies. Educational associations with smoking may vary by personality dispositions, and prevention and intervention programs should consider both sets of factors.

Keywords: Socioeconomic Status, Smoking, Personality Traits, Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), Social Epidemiology

Tobacco smoking is a leading preventable cause of excess morbidity and mortality across the life course (1). Lower Socioeconomic Status (SES), often operationalized through education level, is associated with higher rates of smoking and lower rates of cessation (2-6) Although education represents a commonly used SES indicator in health research (7, 8), one uncertainty is the extent to which educational gradients in smoking status can be explained by other SES indicators such as household income or wealth. The distinction is important because it speaks to whether education itself plays a role in smoking patterns. In other words, is education a critical factor because it involves more access to and/or better ability to process health information? Such advantages may lead to better health decision-making. Or is education merely a proxy for material resources, which promote smoking cessation through purchasing power for stop-smoking programs and aids, and/or confer membership social strata with less temptation to initiate smoking? A secondary SES question is whether education mediates associations between childhood SES and smoking patterns in adulthood.

In addition to education, at least two of the so-called “Big Five” personality factors(9, 10) appear powerfully associated with smoking behaviors: Neuroticism (involving distress-proneness and worry) may be higher, and Conscientiousness (involving reliability, diligence, and achievement-striving) lower in smokers, compared to non-smokers (11, 12). A pair of meta-analyses recently also found that Neuroticism is linked to smoking both in the US and other countries (13, 14). Former smokers—or those who have initiated smoking but successfully stopped—show intermediate levels of Neuroticism and Conscientiousness (11). Some findings also indicate that non-smokers show higher Agreeableness (or altruism, trust, and friendliness) than smokers (11), and mixed findings have been reported for Extraversion (or sociability, vigor, and positive affect) (12) and Openness to Experience (interest in novel ideas and behavior) (15, 16). The Big Five describe the dispositional tendencies of individuals who are susceptible to smoking initiation and maintenance, as well as hinting at psychosocial process involved (i.e., those with higher levels of Neuroticism may smoke to alleviate emotional distress).

A divide exists, however, between SES-uriented or social epidemiologic approaches to smoking investigation, and those focused on individual personality risks. The former rarely measured personality, and the latter rarely consider comprehensive indicators of SES and the role socioeconomic inequalities may play. These two strains of research arise from different disciplinary traditions (social epidemiology vs. epidemiologic personology) with distinct foci (societal inequalities vs. individual disposition) and theories of health behavior (sociological or economic vs. psychological). Yet individual differences in personality operate in conjunction with socioeconomic forces on an everyday basis to determine health behaviors (17) necessitating a better understanding of conjoint SES and personality influences on smoking.

The education-personality interface reveals the extent to which social stratification overpowers individual personality determinants of smoking, vice versa, and/or the degree to which the two interact. Three theoretical models may describe the conjoint roles of personality and education in smoking. First, correlated risks models (18) suggests that SES and personality risk for negative health outcomes cluster in the population. Personality may therefore explain some between-strata SES risk. The cultural-behavioral model suggests that SES influences individual personality configurations that in turn influence smoking status; this formulation implies a mediating role for personality (18). An alternative correlated risk model, indirect selection, holds that personality causes both SES and smoking status, implying a confounding role for personality (19). However, some work suggests reciprocal interrelationships between personality, education, and other components of SES over the lifespan.(20-25). For this reason, life course perspectives on social inequalities suggest that SES-personality risk clustering would be due to mutually reinforcing reciprocal influences between SES and personality over time (19). Few studies have the data to quantify the bidirectional causal influences between personality and SES over time, so the most reasonable interpretation of cross-sectional associations may be that they are product of such life course processes.

Alternatively, personality and SES may be relatively independent risks for some health outcomes. We call this the compensation-accumulation model. It is so named because the risk of smoking associated with social disadvantage may be compensated for by a health-adaptive personality profile, and the protection conferred by social advantage may be offset by the dispositional proclivities toward smoking. Another implication of the independence of SES and personality is that social disadvantage combined with personal propensities toward health-destructive habits represents cumulative risk, while social advantage combined with health-adaptive personality tendencies represent cumulative protection against health-damaging habits. The compensation-cumulation therefore explains within-strata heterogeneity in smoking, or why individuals of similar education level may or may not smoke because of dispositional tendencies.

A final theoretical possibility is that personality traits modify the effects of education on smoking. This has been called a vulnerability model (26, 27) and suggests that personality traits predispose individuals to perceive and respond to similar environmental demands in different ways, with potentially important consequences for socioeconomic gradients in health (28). In other words, educational level may influence smoking status differently, depending on individual disposition. As personality traits have a partially genetic basis, interactions between traits and social environmental features may also represent “down-stream” or distal results of gene-environment interactions (17).

The present investigation examined evidence for these three models in the Midlife Development in the US (MIDUS) national survey. The survey involves a wide age range of US adults (aged 25-74) (29), thus maximizing representation of three distinct smoking classifications: 1) Never smokers, or those who have completely abstained from smoking; 2) Former smokers, or those who had smoked regularly at some point in their lifetime but quit; and 3) Current smokers, or individuals actively smoking.

Method

Participants and Design

The MIDUS study was conducted in 1995 by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and has been described extensively elsewhere (29). It included a number of studies and sub-studies; the data here are from the National Probability Sample. The survey was duly approved by ethical oversight boards, and examined social, behavioral, and psychological factors associated with health through a phone interview and mailed questionnaire. The national probability sample recruited non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults aged 25-74 years (younger and older persons included for comparisons to midlife) using random-digit dialing. The response rate to sampling was 70%, with 4244 persons completing at least the phone interview portion of the study. Of these 4244, 87% returned an accompanying mail survey with at least some part completed. Of these persons 2235 individuals had complete data on all variables and 194 individuals with complete data on all variables except wealth who were also utilized, resulting in an analysis sample of 2429 persons. The greatest portion of missingness was due the outcome variable, smoking. Although sampling weights exist for the study, they did not exist for each of these 2429 persons. As sampling weights must not only be available for all people, but also add to 1 in order to properly calibrate a sample back to the desired reference population, we did not use them.

Instruments

Never, former, and current smoker were determined based on responses to two survey questions: “Have you ever smoked cigarettes regularly--that is, at least a few cigarettes every day?” and “Do you smoke cigarettes regularly NOW?” Individuals answering no to the first were classified as never smokers. Individuals who answered yes to the first and yes to the second were classified as current smokers, and those answering yes to the first and no to the second as former smokers.

Non-education SES indicators were 1) parental occupational status, measured via Duncan’s Socioeconomic Index or SEI, based on 1980 US Census (the highest SEI of mother or father) and standardized to a mean of 0 and SD of 1 according to the overall sample for purposes of interpretability; 2) annual household income; and 3) wealth (assets minus debts, with a positive values equaling some assets, 0 meaning assets equaled debts, and negative values indicating debt). For 194 individuals who had partial assets data indicating some assets or debt but not specific amounts, we used regression imputation based on education, age, gender, race, and occupational status. Household income and wealth were scaled in $10,000 units for interpretability.

Measuring education in years offers the benefits of an interval scale but assumes that each year increment conveys equally meaningful information. The alternative of measuring a few categories such as high school or college uses meaningful markers, but may obscure potentially important gradations between categories and loses information at the extreme ends of the educational spectrum. The MIDUS survey therefore featured an educational scale combining the desirable qualities of both approaches, composed of 12 intervals corresponding to sequential educational milestones (enumerated in Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

|

Overall Sample (N = 2429) |

Never Smokers (N = 735) |

Former Smokers (N = 999) |

Current Smokers (N = 695) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [SD] / N [%] |

Mean [SD] / N [%] |

Mean [SD] / N [%] |

Mean [SD] / N [%] |

|

| Female | 1,115 | 333 | 440 | 342 |

| [45.90%] | [45.31%] | [44.04%] | [49.21%] | |

| Age | 46.81 | 46.81 | 50.58 | 43.93 |

| [12.92] | [12.92] | [12.82] | [11.92] | |

| Black | 125 | 48 | 44 | 33 |

| [5.15%] | [6.53%] | [4.40%] | [4.75%] | |

| Other Race | 109 | 35 | 41 | 33 |

| [4.49%] | [4.76%] | [4.10%] | [4.75%] | |

| Education Scale | 5.84 | 6.48 | 5.97 | 4.98 |

| Mean Level | ||||

| [2.44] | [2.4] | [2.51] | [2.13] | |

| Education Scale Levels | ||||

| 0) No school/ | 10 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| some grade school | [.41%] | [.14%] | [.60%] | [.43%] |

| 1) 8th grade / | 29 | 4 | 13 | 12 |

| junior high school | [1.19%] | [.68%] | [1.3%] | [1.73%] |

| 2) Some high school | 157 | 25 | 60 | 72 |

| [6.46%] | [4.08%] | [6.01%] | [10.36%] | |

| 3) GED | 34 | 2 | 15 | 17 |

| [1.4%] | [.27%] | [6.01%] | [2.45%] | |

| 4) Attended high school | 675 | 162 | 275 | 238 |

| through graduation | [27.79%] | [22.04%] | [27.53%] | [34.24%] |

| 5) 1-2 yrs. College | 479 | 140 | 172 | 167 |

| no degree | [19.72%] | [19.05%] | [17.22%] | [24.03%] |

| 6) 3+ yrs. College | 113 | 42 | 41 | 30 |

| no degree | [4.65%] | [5.71%] | [4.1%] | [4.32%] |

| 7) 2 year college | 162 | 51 | 67 | 44 |

| Degree | [6.67%] | [6.94%] | [6.71%] | [6.33%] |

| 8) 4 year college degree | 441 | 171 | 199 | 71 |

| [18.16%] | [23.27%] | [19.92%] | [10.22%] | |

| 9) Some graduate school | 66 | 34 | 25 | 7 |

| [2.72%] | [4.63%] | [2.5%] | [1.01%] | |

| 10) Masters degree | 180 | 63 | 94 | 23 |

| [7.41%] | [8.57%] | [9.41%] | [3.31%] | |

| 11) Doctoral degree | 83 | 40 | 32 | 11 |

| [3.42%] | [5.44%] | [3.2%] | [1.58%] | |

| Parental SEI | 38.02 | 39.64 | 38.22 | 36.01 |

| [13.67] | [13.98] | [13.87] | [12.77] | |

| Household | $50,000 | $55,500 | $51,500 | $45,000 |

| Incomea | [$28,500 – $88,000] | [$32,000 - $101,500] | [$29,500 – $90,000] | [$26,000 – $76,500] |

| Wealtha | $27,500 | $32,500 | $47,500 | $9,500 |

| [$0 – $125,000] | [$0 – $125,000] | [$500 – $175,000] | [$0 – $62,500] | |

| Neuroticism | 2.26 | 2.20 | 2.82 | 2.31 |

| [.67] | [.60] | [.66] | [.70] | |

| Extraversion | 3.19 | 3.19 | 3.16 | 3.22 |

| [.56] | [.56] | [.59] | [.53] | |

| Openness | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.05 | 3.08 |

| [.52] | [.52] | [.53] | [.52] | |

| Agreeableness | 3.46 | 3.42 | 3.45 | 3.51 |

| [.50] | [.52] | [.50] | [.48] | |

| Conscientiousness | 3.46 | 3.43 | 3.38 | 3.35 |

| [.45] | [.42] | [.45] | [.48] | |

Note. SEI = Duncan’s Socioeconomic Index. Parental SEI and personality traits scores reported in raw score units.

= values are median [interquartile range]

The Big Five personality traits were assessed with the Midlife Development Inventory Big Five scales (30), composed of 4-7 trait terms for each of the Big Five. Respondent rated how well each trait described them on a four point Likert scale from “A lot” to “Not at all”, with scale scores averaged across items. These scales were developed from a pool of established Big Five trait adjectives (31) by selecting the smallest number of items that accounted for 90% of the variance in total scales scores in an initial scale development sample, based on item-total correlations, regression-based selection, and high factor loadings (30). Factor analyses conducted during scale construction indicated that these adjectives reflected their intended Big Five latent dimensions (30). Cronbach’s alpha estimates of internal consistency for each scale were: Neuroticism, .74; Extraversion, .78; Openness to Experience, .77; Agreeableness, .80; and Conscientiousness, .58. Scale scores were standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 based on the overall sample for interpretability.

Demographic covariates consisted of gender (0=male 1= female), age, and race/ethnicity (one indicator variable for African American and one for other race, Caucasian reference category).

Analyses

Analyses consisted of a series of multinomial logit models. These models are similar to typical logistic regression but allow for more than two outcome categories. The antilogs of estimated parameters are called Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs). Relative Risks (RRs) are ratios of probabilities, such as the probability of current smoking over the probability of never smoking. RRRs are ratios of RRs: for instance, a numerator that is the probability of current smoking over never smoking in women, over a denominator that is the probability of current smoking over never smoking in men. We were interested in distinguishing both lifetime abstinence and former smoking from current smoking, so current smoking was designated as the “base outcome” against which lifetime abstinence and lifetime cessation were contrasted. RRRs with values above 1 indicate the percent increase in RR for the outcome category of interest vs. the base category, associated with a one unit increase in the independent variable (IV). RRRs below 1 indicate the percent decrease in RR associated with a one unit increase in the IV. If one wants instead know the risk associated with a one unit decrease in an IV that is protective (i.e., RRR below 1), the inverse of the RRR can be taken.

We began with a model (Model 1) involving demographic covariates and childhood SES. Model 2 added education, Model 3 added household income, and Model 4 added personality traits. At each step, we examined whether odds ratios changed by more than 10% to evaluate the potential confounding effect of financial variables and personality on education, and education upon childhood SES. This method of assessing confounding is called the “change in estimate” criteria (32). When estimates shift due to the inclusion of a covariate, it means that the covariate is related to both the IV of interest and the outcome. The 10% change criteria is a typical benchmark for confounding in public health research (32), and when dealing with RRRs and similar risk estimates, the determination is made by taking (RRR of model 1 — RRR of model 2)/(RRR of model 1 - 1).

Next, we examined multiplicative interactions by testing product terms between each of the Big Five and education, one at a time. For each of our two outcomes of interest, RRR of never smoking, and RRR of former smoking, we controlled Type I error inflation from multiple interaction tests by application of the False Discovery Rate (FDR).(33) We tested additive interactions using recently published methods for continuous variables.(34) Additive interactions reflect the fact that the presence of two factors together may elevate risk more than the sum of their individual effects, but not to the degree expected by the product of their individual effects (35). The Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction (RERI) is an additive interaction index quantifying additional risks due to simultaneous 1 unit increases in two continuous predictors. It is equal to the difference between the increase in RRRs observed for simultaneous one unit increments in both factors, and the increase that would be expected from their sum if they did not interact (34).

An example may help clarify. If the observed effect of one unit increases in the two risk factors is an RRR of 1.8 (i.e., an 80% increase risk), but the expected effect of one unit increases under additive independence is 1.7, the RERI is .10, indicating an additional 10% increase in risk due to additive interaction. Additive interaction point estimates, standard errors, p-values, and 95% CIs were estimated by bootstrapping (34) and p-values were subjected to the FDR. Analyses were conducted in Stata 10, Special Edition (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the overall sample as stratified into never (N=735), current (N=999), and former smokers (N=695). Table 2 shows the correlations among the variables. Education was modestly correlated with parental SEI (.36) and assets (.29). Correlations between SES indicators and personality traits were .10 and less, although Openness showed modest correlations with education (.31) and parental SEI (.14).

Table 2.

Variable Correlations

| Female | Age | Blacka | Other Racea |

Edu- cation |

Parental SEI |

HH Income |

Wealth | Neurot- icism |

Extra- version |

Open- ness |

Agree- ableness |

Conscient- Iousness |

Former Smokeb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -.04 | |||||||||||||

| .068 | ||||||||||||||

| Blacka | .05 | -.04 | ||||||||||||

| .020 | .040 | |||||||||||||

| Other Racea | -.04 | -.13 | -.05 | |||||||||||

| .030 | .000 | .013 | ||||||||||||

| Education | -.09 | -.02 | -.06 | .02 | ||||||||||

| .000 | .228 | .002 | .370 | |||||||||||

| Parental SEI | .01 | -.15 | -.15 | .00 | .36 | |||||||||

| .463 | .000 | .000 | .836 | .000 | ||||||||||

| HH Income | -.12 | -.08 | -.06 | -.04 | .29 | .14 | ||||||||

| .000 | .000 | .002 | .066 | .000 | .000 | |||||||||

| Wealth | -.09 | .37 | -.10 | -.08 | .19 | .09 | .27 | |||||||

| .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||||||

| Neuroticism | .14 | -.17 | -.03 | .00 | -.10 | .01 | -.05 | -.12 | ||||||

| .000 | .000 | .117 | .956 | .000 | .643 | .016 | .000 | |||||||

| Extraversion | .08 | -.02 | .02 | .03 | -.02 | .04 | .05 | .01 | -.13 | |||||

| .000 | .331 | .381 | .185 | .414 | .072 | .013 | .633 | .000 | ||||||

| Openness | -.07 | -.05 | .02 | .03 | .21 | .14 | .07 | .02 | -.14 | .53 | ||||

| .001 | .008 | .349 | .160 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .229 | .000 | .000 | |||||

| Agreeableness | .26 | .04 | .03 | .01 | -.10 | -.02 | -.04 | -.04 | -.02 | .55 | .38 | |||

| .000 | .049 | .118 | .757 | .000 | .231 | .040 | .042 | .301 | .000 | .000 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | .10 | .06 | -.03 | -.02 | .08 | .01 | .10 | .07 | -.19 | .26 | .25 | .29 | ||

| .000 | .002 | .217 | .359 | .000 | .566 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||

| Former Smokerb | -.03 | .24 | -.03 | -.02 | .04 | .01 | .01 | .13 | .02 | -.04 | -.02 | -.01 | -.01 | |

| .124 | .000 | .167 | .446 | .032 | .542 | .620 | .000 | .251 | .056 | .303 | .528 | .542 | ||

| Current Smokerb | .04 | -.14 | -.01 | .01 | -.22 | -.09 | -.10 | -.15 | .05 | .04 | .02 | .07 | -.05 | -.53 |

| .039 | .000 | .574 | .695 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .024 | .040 | .227 | .001 | .013 | .000 |

Note.N = 2429. For each entry, top number is Pearson r, bottom number is p-value. SEI = Duncan’s Socioeconomic Index. HH = Household income. Correlations involving continous variables and indicator variables for black, other race, former and current smoker are biserial, while those between indicators are phi.

= reference category of Caucasian race/ethnicity.

= reference category of never smoker.

Table 3 shows RRRs for lifetime abstinence vs. current smoking from multinomial logit models. Model 1 revealed that higher parental SEI was associated with greater likelihood of never smoking, but adjustment for education in Model 2 rendered this effect non-significant. Higher education was significantly associated with never smoking, such that an increase of 1 educational mile stone increased the RR of never vs. ever smoking by 31%. This effect was robust, remaining virtually unchanged when adjusting for household income and wealth in Model 3 and personality in Model 4. Greater wealth was also associated with never smoking after adjustment for personality, although household income was not. Finally, a 1 SD increase in Openness—or the equivalent of moving from the 50th to the 84th percentile on this trait—reduced the RR of never smoking by 22%. A 1 SD increase in Conscientiousness increased the RR of never smoking by 20%. Black race/ethnicity was also associated with greater likelihood of lifetime abstinence.

Table 3.

Likelihood of Never vs. Current Smoking as a Function of SES and Personality

|

Model 1: Demographics & Childhood SES |

Model 2: Model 1 + Education |

Model 3: Model 2 + Economic Indicators Model |

Model 4: Model 3 + Personality Traits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| [0.69,1.04] | [0.75,1.15] | [0.77,1.19] | [0.76,1.21] | |

| Age | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| [1.00,1.02] | [1.00,1.02] | [0.99,1.01] | [0.99,1.01] | |

| Black | 1.79* | 1.84* | 1.97** | 2.08** |

| [1.12,2.86] | [1.14,2.97] | [1.22,3.18] | [1.28,3.38] | |

| Other Race | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 1.09 |

| [0.65,1.76] | [0.61,1.68] | [0.64,1.78] | [0.65,1.83] | |

| Parental SEI | 1.37*** | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.10 |

| [1.22,1.53] | [0.96,1.23] | [0.95,1.21] | [0.97,1.24] | |

| Education | 1.31*** | 1.28*** | 1.29*** | |

| [1.24,1.38] | [1.22,1.35] | [1.23,1.37] | ||

| Household Income | 1.02* | 1.02 | ||

| [1.00,1.05] | [1.00,1.04] | |||

| Wealth | 1.01* | 1.01* | ||

| [1.00,1.01] | [1.00,1.01] | |||

| Neuroticism | 0.91 | |||

| [0.81,1.02] | ||||

| Extraversion | 1.07 | |||

| [0.92,1.23] | ||||

| Openness | 0.78*** | |||

| [0.68,0.90] | ||||

| Agreeableness | 0.88 | |||

| [0.76,1.00] | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 1.20** | |||

| [1.07,1.35] |

Note. Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs); 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Personality traits and parental SEI standardized to MIDUS sample mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

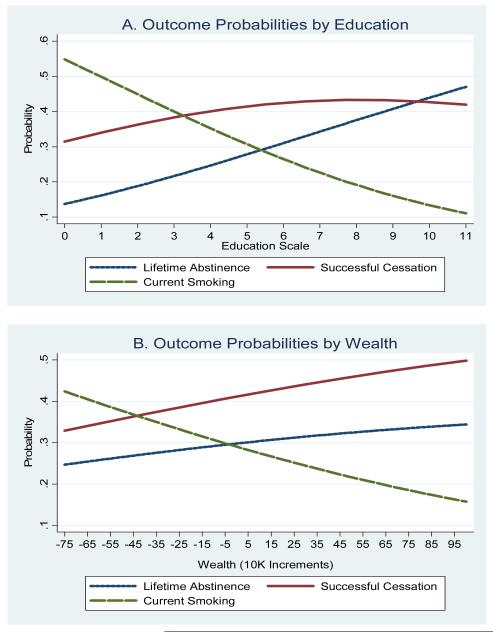

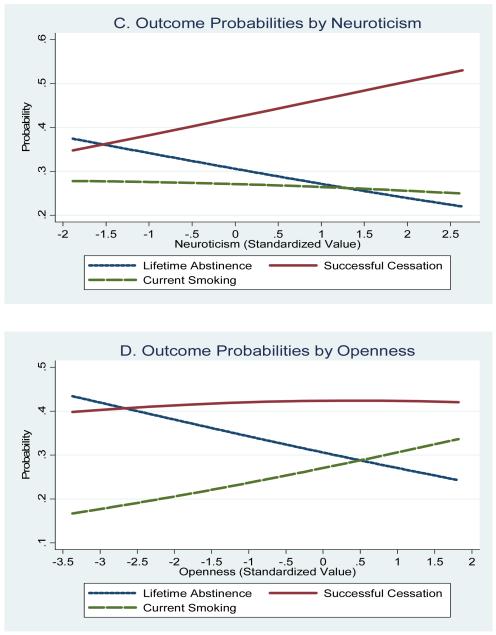

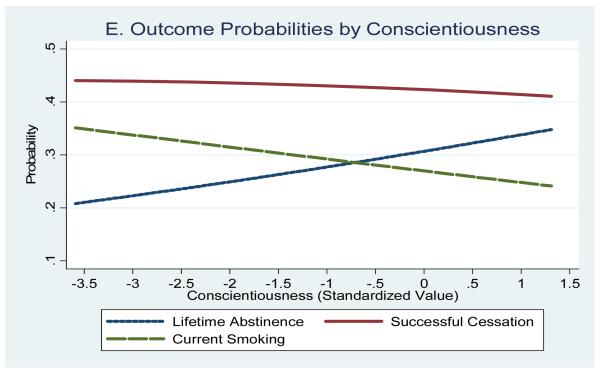

Table 4 presents factors associated with RR of the second multinomial outcome, former vs. current smoking. An initially strong association between higher parental SEI and former smoking was again diminished by education (although parental SEI remained significant in the final model). Each additional level of education increased the RR of successful lifetime cessation by 20%, an effect undiminished by finances or personality, and greater wealth was again associated with cessation even after adjustment for personality. A 1 SD increase in Neuroticism increased the RR of successful cessation by 20%. Greater age was also associated with higher likelihood of successful cessation. Figure 1, panels A-E present the probability of each smoking outcome according to levels of education, wealth, Neuroticism, Openness, Conscientiousness.

Table 4.

Likelihood of Former vs. Current Smoking as a Function of SES and Personality

|

Model 1: Demographics & Childhood SES |

Model 2: Model 1 + Education |

Model 3: Model 2 + Economic Indicators Model |

Model 4: Model 3 + Personality Traits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| [0.68,1.02] | [0.72,1.07] | [0.74,1.11] | [0.70,1.09] | |

| Age | 1.05*** | 1.05*** | 1.04*** | 1.04*** |

| [1.04,1.05] | [1.04,1.05] | [1.03,1.05] | [1.03,1.05] | |

| Black | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.37 | 1.46 |

| [0.78,2.04] | [0.79,2.09] | [0.84,2.23] | [0.90,2.38] | |

| Other Race | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.27 |

| [0.74,1.97] | [0.71,1.91] | [0.75,2.00] | [0.77,2.08] | |

| Parental SEI | 1.32*** | 1.13* | 1.12 | 1.13* |

| [1.18,1.47] | [1.01,1.27] | [0.99,1.25] | [1.01,1.27] | |

| Education | 1.20*** | 1.17*** | 1.19*** | |

| [1.14,1.26] | [1.12,1.23] | [1.13,1.25] | ||

| Household Income | 1.02 | 1.02 | ||

| [1.00,1.04] | [0.99,1.04] | |||

| Wealth | 1.01* | 1.01** | ||

| [1.00,1.01] | [1.00,1.01] | |||

| Neuroticism | 1.12* | |||

| [1.01,1.25] | ||||

| Extraversion | 0.97 | |||

| [0.85,1.12] | ||||

| Openness | 0.88 | |||

| [0.78,1.01] | ||||

| Agreeableness | 0.95 | |||

| [0.83,1.08] | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 1.06 | |||

| [0.95,1.19] |

Note. Relative Risk Ratios; 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Personality traits and parental SEI standardized to MIDUS sample mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Probabilities of Lifetime Abstinence, Successful Cessation, or Current Smoking by SES (Panels A-B) and Personality (Panels C-E) Factors

Effect modification analyses revealed no multiplicative interactions between education and personality traits for either never smoking or former smoking, and no additive interactions reached significance for former smoking. Two small additive interactions were observed for never smoking. The combined effect of a 1 SD increase in Conscientiousness and one level increase in education was slightly greater than expected under additive independence (RERI [95% CI] = .06 [.01 - .12], p = .003). Similarly, the combined effect of conjoint decreases of 1 SD in Openness and increases of 1 unit of education was greater than expected under additive independence (RERI [95% CI] = .07 [.01 - .13]), p = .019). Table 5 presents the adjusted RRRs for additive interactions of average (i.e., z-score = 0) vs. low (z-score = -1) Openness and high-school vs. 1-2 years beyond high school education (i.e., a 1 unit increase on the education scale), as well as for education and average vs. high (z-score = 1) Conscientiousness.

Table 5.

Adjusted Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs) for Never Having Smoked vs. Current Smoking by Combinations of Personality Traits and Education.

| Openness + Education | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education Level = High School |

Education Level = 1-2 years post- high school, no degree |

|

| Openness z-score = 0 | 1 | 1.29 |

| Openness z-score = -1 | 1.24 | 1.76 |

| Expected RRR under independent additivity = 1.24 + 1.29 − 1 = 1.53 | ||

| Conscientiousness + Education | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education Level = High School |

Education Level = 1-2 years post- high school, no degree |

|

| Conscientiousness z-score = 0 | 1 | 1.29 |

| Conscientiousness z-score = 1 | 1.23 | 1.64 |

| Expected RRR under independent additivity = 1.23 + 1.59 − 1 = 1.52 | ||

Note. Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) adjusted for all factors in Model 4 (Table 3). Bolded entries denote observed RRRs which RRRs expected under additive independence (i.e., not interaction) noted in italics. Additive interactions computed through bootstrapping the Relative Excess Risk Due to Interaction (RERI).

CONCLUSIONS

Based on three theoretical models, we examined whether educational gradients in lifetime abstinence and cessation from smoking were confounded by financial status or personality traits, and whether the latter interacted with education in relation to smoking patterns. People with higher levels of education are more likely to have never smoked, and more likely to have stopped smoking. This was true even after controlling for wealth and household income. Personality also did not diminish education associations with smoking status. People with higher levels of Conscientiousness and lower levels of Openness were more likely to have never smoked, and those who were higher in Neuroticism are more likely to have stopped smoking. Thus, results favor a compensation-accumulation model in which education and personality associations with smoking status are largely independent. A pair of small additive interactions was also noted, such that conjoint increases in education and Conscientiousness increased the likelihood of never smoking slightly beyond the sum of their independent effects, as did conjoint increases in education and decreases in Openness. Thus, results offer some modest support for a vulnerability model as well, in which lower Conscientiousness and higher in Openness may slightly amplify smoking risk associated with lower education. Our results extend well-documented findings on educational gradients in smoking patterns in three ways.

First, many population-based surveys demonstrate educational gradients in smoking without concomitant adjustment for income and wealth. Our findings suggest that while greater wealth is also associated with both never smoking and successfully quitting, education confers additional advantage. In contrast to wealth, which may decrease as a result of direct and indirect smoking costs, the direction of influence is clearer for education. Education may confer non-financial advantages for initially abstaining from, as well as stopping smoking. Education enhances cognitive resources, quality of decision making, access to health information, and improves health literacy (36). Education may also bring access to peer groups or social contexts where smoking is less normative. In such contexts, efforts to quit may be strongly supported and temptations to begin fewer. Finally, education also substantially diminished the associations of higher parental occupational status with both never and former smoking. These findings suggest that education may also be an important intermediary link in a life course risk chain (37) between childhood social disadvantage and adult smoking patterns, consistent with findings of naturalistic experiments that indicate the provision of additional education reduces later smoking risk (38, 39).

A second important finding was that educational gradients in smoking cannot be explained by personality traits, which often remain unmeasured in epidemiologic studies. The present results rule out confounding by personality, and also suggest that two traits are associated with never smoking while a third is associated with successful cessation of smoking. Importantly, the interface of personality and SES in this case suggests that psychological and socioeconomic correlates of smoking are independent. The implication is that after differences in smoking between socioeconomic strata have been accounted for, individuals’ personalities explain some of the remaining heterogeneity in smoking among persons of similar SES. The tendency to smoke may be offset by higher Conscientiousness and lower Openness. Buffers against smoking provided by social advantage may be obliterated by deficits in Conscientiousness and surfeits of Openness to Experience.

With respect to specific traits, the link between greater Conscientiousness and never smoking is consistent with prior work (11, 12) and probably reflects generally better healthier behavior (40) and more conservative health risk evaluation (41-43) than persons lower in Conscientiousness. Although some prior reports have found no association between Openness and smoking (16), others have found that lower Openness is predictive of abstinence after smoking cessation treatment (15). We observed strong associations between lower Openness and greater likelihood of never initiating smoking, a finding that is consistent with the tendency of people lower in Openness to refrain from behavioral experimentation (44), including the smoking of non-nicotinic substances such as marijuana (45).

Neuroticism increased, rather than decreased the likelihood of having quit smoking, relative to current smoking. This is different than prior reports in a much older samples that levels of Neuroticism in former smokers are lower than in current smokers (11). However, it is consistent with the notion Neuroticism can have health-protective effects by increasing health vigilance and worry (46), resulting in adaptive health behavior change. Within the limits of cross-sectional data, this interpretation seems particularly possible given that the Neuroticism scale used in MIDUS was heavily loaded with items indicating apprehension. It is also consistent with the results of a recent intervention trial (47) which found that the effectiveness of health messages encouraging smoking cessation was largely mediated by anxiety over potential health problems. As well, persons higher in Neuroticism are more vigilant to threats (48), and individual differences in the perceptions of the need for health-protective action are tied to the extent people perceive negative outcomes as both probable and severe (49).

The third finding was that education appears to interact additively to a small degree with both Openness and Conscientiousness in differentiating never smokers from current smokers. This provides minor support for a vulnerability model: persons lower Conscientiousness and higher Openness represent a group more susceptible to the risk of smoking initiation associated with less education. This makes intuitive sense, in that persons lacking in Conscientiousness and higher in Openness combine poor self-restraint with exploratory attitudes toward behavior, including possibly dangerous behavior. Modification of SES risk by personality traits may also represent a distal or attenuated manifestation of gene-environment interaction (17), in the form of synergy between phenotypic and social-environmental risk.

With respect to other findings, greater wealth distinguished both never smokers and those who had quit smoking from current smokers, reflecting the possibility that wealth confers entrée in social circles where smoking is less prevalent and/or tolerated. The findings may also be explained in part by the economic advantages of abstaining from or quitting smoking. Individuals who are older are probably more likely to have quit because they have had more time to. African American race/ethnicity was also robustly associated with never smoking, and while the sample precluded definitive analyses of racial/ethnic differences, this finding is consistent with prior research documenting lower rates of smoking initiation among African Americans. The reasons for this deserve further investigation.

Implications from a public health perspective suggest, first, that personality should be taken into account in intervention programs and public health messages. Media health promotion efforts might pair images of lung damage or cancer risk with individuals depicted as having a reckless, undisciplined (low Conscientiousness), and overly experimental (high Openness) approach to life. This would stand in contrast to typical marketing strategies used by the manufacturers, which pair the act of smoking with manifestations of socially attractive qualities often associated with these traits: bold spontaneity (rather than caution), self-indulgence (rather than self-discipline), and an adventuresome, “live for today” attitude (rather than prudent abstention from dangerous behavioral experimentation).

In clinical health care contexts where time and resources are limited, findings suggest it is not just the less educated, but the less educated and less worried who are most in need of available cessation resources. Indeed, if anxiety functions as an important mediator of smoking cessation, intervention efforts engendering appropriate anxiety over the negative health consequences of smoking would appear warranted. At the level of universal prevention, our findings also support a need for the enhancement of educational opportunities and attendant health literacy. However, targeted interventions could be offered to high-risk demographic groups and tailored interventions might profitably incorporate personality information.

Finally, findings have implications for health policy debates over individual vs. social responsibility for health destructive behavior (50-52). Our results suggest that while smoking is strongly related to social inequalities in the distribution of resources, it is also a function of personal propensities. This supports an approach to health policy holding both individuals and society responsible for smoking behavior. An example of this is the liberal egalitarian policy model, which penalize individuals for poor health behavior through taxing the behavior (i.e., purchasing cigarettes). However, the model preserves social responsibility by seeking to equalize, rather than differentially allocate care for health conditions on the basis of individual responsibility for creating such conditions (53).

Findings must be interpreted within the context of study strengths and limitations. Because the data were cross-sectional, we lacked the ability to assess temporal relationships between variables or ascertain causal sequences. For instance, we were unable to assess the role of childhood personality traits in adult smoking. Longitudinal follow-up work will be critical in refining causal inferences. Another important caveat of cross-sectional analyses is that while childhood SES refers to a period earlier in time than adult personality, both were measured simultaneously. Thus, mediation and confounding are impossible to disentangle in this situation, as they are statistically identical (54). We also cannot exclude the possibility that unmeasured confounders, such as cognitive ability, account for some of the effects of education or personality. However, natural experimental findings imply that induced increases in years of education are associated with higher rates of cessation regardless of cognitive ability (38, 39). The personality scales involved small numbers of items, underscoring differences in measures designed for epidemiologic surveys vs. clinical assessments (55). Brief scales may contain more error variance, masking associations, increasing Type 2 error rates, and underscoring the need to address measurement error analytically. Last, classification of lifetime abstinence, cessation, or current smoking may have been affected by reporting or recall biases (56), although the confidential nature of the survey was designed to reduce the first and the use of a relatively open-ended time period (i.e., “did you ever” smoke regularly) designed to reduce the second. Prior findings also indicate non-differential misclassification of smoking status with respect to SES (57). Additionally, we were unable to differentiate a modest history of experimentation with smoking from more prolonged and consistent former smoking, and each may be differentially linked to traits and SES factors.

Strengths of the study were the conjoint estimation of SES and personality effects, comprehensive and non-arbitrary coverage of personality traits and SES indicators, examination of different theoretical models for the personality-SES-health interface, use of a national sample with coverage of the majority of the adult life course, and methodological efforts to investigate both additive and multiplicative interactions while balancing Type I and II errors. In daily life, both individual personality traits and socioeconomic forces work in tandem to influence health outcomes. Our results suggest both sets of factors play important roles in smoking behavior. Future work is needed to understand how these two powerful sources of influence work in conjunction to influence other health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Support: Preparation of this manuscript was supported by United States Public Health Grant T32 MH073452, to Jeffrey Lyness and Paul Duberstein, and K08AG031328 to Ben Chapman.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None

References

- 1.World Health Organization . The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federico B, Costa G, Kunst AE. Educational inequalities in initiation, cessation, and prevalence of smoking among 3 italian birth cohorts. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(5):838–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst AE, Geurts JJM, et al. Educational differences in smoking: International comparison. Br Med J. 2000;320(7242):1102–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7242.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, et al. Trends in cigarette-smoking in the united-states - educational-differences are increasing. JAMA. 1989;261(1):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Droomers ML, Schrijvers CTM, Mackenbach JP. Why do lower educated people continue smoking? explanations from the longitudinal GLOBE study. Health Psychology. 2002;21(3):263–72. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez E, Schiaffino A, Garcia M, et al. Widening social inequalities in smoking cessation in spain, 1987-1997. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(10):729–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.10.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galobardes B, Smith GD, Lynch JW. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):95–101. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol. 1993;48(1):26, 34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist. 1997;52:509–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terracciano A, Costa PT. Smoking and the five-factor model of personality. Addiction. 2004;99(4):472–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert DG, Gilbert BO. Personality, psychopathology, and nicotine response as mediators of the genetics of smoking. Behav Genet. 1995;25(2):133–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02196923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The five-factor model of personality and smoking: A meta-analysis. J Drug Ed. 2006;36(1):47–58. doi: 10.2190/9EP8-17P8-EKG7-66AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munafo MR, Zetteler JI, Clark TG. Personality and smoking status: A meta-analysis. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2007;9(3):405–13. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooten WM, Wolter TD, Ames SC, et al. Personality correlates related to tobacco abstinence following treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(1):59–74. doi: 10.2190/N9F1-1R9G-6EDW-9BFL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Stress, smoking motives, and psychological well-being: The illusory benefits of smoking. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1981;3:125–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine . In: Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the Nature/Nurture debate. Hernandezx LM, Blazer DG, editors. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black DS, Townsend P, Davidson N. Inequalities in health: The black report. Penguin; Harmondsworth: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blane D, Bartley M, Smith G Davey. Making sense of socio-economic health inequalities. In: Field DTS, editor. Sociological Perspectives on Health, Illness, and Health Care. Blackwell Science; 1998. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.John OP, Caspi A, Robins RW, et al. The little 5 - exploring the nomological network of the 5-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Dev. 1994;65(1):160–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borghans L, Duckworth AL, Heckman JJ, ter Weel B. The economics and psychology of personality traits. NBER;Working Paper No. 13810. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohn ML, Schooler C. Occupational experience and psychological functioning: An assessment of reciprocal effects. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(1):97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohn ML, Schooler C. The reciprocal effects of the substantive complexity of work and intellectual flexibility: A longitudinal assessment. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84(1):24–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn ML, Schooler C. Job conditions and personality: A longitudinal assessment of their reciprocal effects. American Journal of Sociology. 1982;87(6):1257–86. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Kortteinen M, et al. Socioeconomic status, hostility and health. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(3):303–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kivimaki M, Elovainio M, Kokko K, et al. Hostility, unemployment and health status: Testing three theoretical models. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2139–52. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adler N, Matthews K. Health psychology: Why do some people get sick and some stay well? Annu Rev Psychol. 1994;45:229, 259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. The MIDUS national survey: An overview. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kesller RC, editors. How Health Are We? A National Study of Well Being at Midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2004. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The midlife development inventory (MIDI) personaltiy scales: Scale construction and scoring. Bradeis University Psychology Department MS 062. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(1):26–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mickey R, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:125–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knol MJ, van der Tweel I, Grobbee DE, Numans ME, Geerlings M. Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model. Int J Epi. 2007;36:1111–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An introduction. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Bruin W Bruine, Parker AM, Fischhoff B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(5):938–56. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, et al. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):778–83. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimard FPD. Education and smoking: Were vietnam war draft avoiders more likely to avoid smoking? Journal of Health Economics. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Walque D. Does education affect smoking behaviors? evidence using the vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. Journal of Health Economics. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887, 919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soane E, Chmiel N. Are risk preferences consistent? the influence of decision domain and personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(8):1781–91. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, et al. Conscientiousness, perceived risk, and risk-reduction behaviors: A preliminary study. Health Psychology. 2000;19(5):496–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, et al. Personality traits, perceived risk, and risk-reduction behaviors: A further study of smoking and radon. Health Psychology. 2006;25(4):530, 536. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCrae RR. Openness to experience: Expanding the boundaries of factor V. European Journal of Personality. 1994;8(4):251–72. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, et al. The relations among personality, symptoms of alcohol and marijuana abuse, and symptoms of comorbid psychopathology: Results from a community sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10(4):425–34. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. J Pers. 2000;68(6):1089–107. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Magnan RE, Koblitz AR, Zielke DJ, McCaul KD. The effects of warning smokers on perceived risk, worry, and motivation to quit. Ann Beh Med. 2009;37:46–57. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nettle D. The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. Am Psychol. 2006;61(6):622, 631. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinstein ND. Perceived probability, perceived severity, and health-protective behavior. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1):65–74. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wikler D. Personal and social responsibility for health. Ethics & Int Aff. 2002;16(2):47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2002.tb00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wikler D. Who should be blamed for being sick? Health Ed Q. 1987;14(1):11–25. doi: 10.1177/109019818701400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minkler M. Personal responsibility for health? A review of the arguments and the evidence at century’s end. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26(1):121–40. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cappelen AW, Norheim OF. Responsibility in health care: A liberal egalitarian approach. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(8):476–80. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.010421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gallacher JEJ. Methods of assessing personality for epidemiologic-study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46(5):465–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.5.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krall EA, Valadian I, Dwyer JT, et al. Accuracy of recalled smoking data. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(2):200–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suadicani P, Hein HO, Gyntelberg F. Serum validated tobacco use and social inequalities in risk of ischemic-heart-disease. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(2):293–300. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]