Summary

Oxygen supplementation is used as therapy to support critically ill patients with severe respiratory impairment. Although hyperoxia has been shown to enhance the lung susceptibility to subsequent bacterial infection, the mechanisms underlying enhanced susceptibility remain enigmatic. We have reported that disruption of Nrf2, a master transcription regulator of various stress response pathways, enhances susceptibility to hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury (ALI) in mice, and have also demonstrated an association between a polymorphism in the NRF2 promoter and increased susceptibility to ALI. In this study, we show that Nrf2-deficient (Nrf2−/−) but not wild-type (Nrf2+/+) mice exposed to sub-lethal hyperoxia succumbed to death during recovery after P. aeruginosa infection. Nrf2-deficiency caused persistent bacterial pulmonary burden and enhanced levels of inflammatory cell infiltration as well as edema. Alveolar macrophages isolated from Nrf2−/− mice exposed to hyperoxia displayed persistent oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine expression concomitant with diminished levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as Gclc, required for GSH biosynthesis. In vitro exposure of Nrf2−/− macrophages to hyperoxia strongly diminished their antibacterial activity and enhanced inflammatory cytokine expression compared to Nrf2+/+ cells. However, GSH supplementation during hyperoxic insult restored the ability of Nrf2−/− cells to mount antibacterial response and suppressed cytokine expression. Thus, loss of Nrf2 impairs lung innate immunity and promotes susceptibility to bacterial infection after hyperoxia exposure, ultimately leading to death of the host.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, acute lung injury, macrophages, Marco, bacterial exacerbation

INTRODUCTION

Oxygen supplementation, often leading to hyperoxia, is widely used to support critically ill patients with non-infectious and infectious acute lung injury (ALI) and in treating exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease. However, prolonged hyperoxia causes histopathological changes similar to acute lung injury in rodents (1). Experimental evidence obtained from various laboratories has shown that hyperoxia induces ALI by causing both lung epithelial and endothelial cell death leading to the disruption of epithelial and blood barrier integrity (1–3). Although excessive production of reactive electrophiles contributes to the development of ALI (4, 5), the mechanisms underlying repair processes and inflammatory responses, as well as enhanced susceptibility to viral or bacterial infections during the recovery phase of ALI are not clearly understood.

NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription factor that modulates cellular stress by regulating the expression of genes encoding several cellular detoxifying enzymes via the antioxidant response element (ARE) (6). Nrf2 deficiency is known to cause diminished levels of basal and inducible expression of several stress response pathways crucial for both detoxification of reactive electrophiles generated by prooxidants during repair processes (see review (7)). Targeted deletion of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility of the lung to hyperoxia (8, 9). We have recently demonstrated that deletion of Nrf2 in mice leads to alveolar cell growth arrest and enhances cell sensitivity to prooxidants accompanied by a deregulated antioxidant transcriptional program both in vivo and in vitro (10, 11). In agreement with these results, administration of GSH to Nrf2−/− mice reverses these phenotypes. We also demonstrated persistently increased inflammation and cellular infiltration in the lungs of Nrf2−/− mice exposed to sub-lethal hyperoxia during recovery (12). Given that patients subjected to oxygen supplementation in intensive care units often suffer from infections such as pneumonia which cause excess morbidity and mortality (13), we examined whether a dysfunctional Nrf2-ARE signaling enhances susceptibility to bacterial infection during recovery from hyperoxia. We provide for the first time evidence of an impairment of innate immunity against P. aeruginosa infection following hyperoxic lung injury in Nrf2−/− mice, which occurs in part from deregulated alveolar macrophage response.

METHODS

Hyperoxia exposure, P. aeruginosa infection, and assessment of lung injury and inflammation

The wildtype (Nrf2+/+) and Nrf2-deficient (Nrf2−/−) CD1/ICR strains of mice (6–8 weeks, 25–30 grams) were exposed to hyperoxia (95% oxygen) or room air (RA) as previously described (12). Mice were then infected with low (105 colony forming units (cfu)) and high (106 cfu) doses of P. aeruginosa O1 constitutively expressing GFP (gift from Dr. Terry Manchen, University of California, Berkeley) (14) for 4 h and 72 h, respectively. After infection, lung inflammation was evaluated by differential cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of the right lung as previously described (12). The left lung was inflated to 25 cm of water pressure and fixed with 0.8% low-melting agarose in 1.5% buffered paraformaldehyde for 24 h, and 5 μm lung sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Differential cell counts were performed after staining the cells with Diff-Quik stain kit (Dade Behring, Laboratory Supplies). All experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the institutional animal care use committee of the Johns Hopkins University.

In vivo bacterial clearance

Ampicillin-resistant P. aeruginosa bacteria expressing EGFP, grown from a single colony, were used throughout the study. The bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth overnight at 37°C and the bacterial numbers were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions on ampicillin-agar plates and counting colonies. BAL fluids and lung (right middle lobe) tissues were collected at 4 h and 72 h post-infection and respiratory bacterial burdens were measured by incubating serial 10-fold dilutions of BAL fluid and lung homogenates on ampicillin-agar plates at 37°C overnight. The cfu were enumerated and the total number of bacteria present in the BAL fluid and in the lung was quantified. The results were expressed as the total cfu present both in the total BAL fluid and lung tissue.

In vitro bactericidal assay

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity of mice administered with 2% thioglycolate using a standard protocol. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then immediately exposed to hyperoxia for 24 h prior to bacterial infection. Live bacterial numbers were determined by plating the cell lysates on to ampicillin containing agar plates.

Real-time RT-PCR

The expression levels of various genes were quantified in triplicate by TaqMan® gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, CA) using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) and mitochondrial ribosomal protein L32 (Mrpl32) (n = 3–4 per group) as internal control genes. The absolute expression values for each gene was normalized to that of gapdh/Mrpl32 and values from room air samples set as one unit. Each experiment was repeated and n of at least 3 was derived from two independent experiments.

Cytokine measurements in BAL fluids

BAL samples were analyzed for IL-6 protein content using ELISA Quantikine Mouse IL-6 Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Equal protein from the BAL samples were incubated in microplates pre-coated with a monoclonal antibody specific for mouse Il-6 for 2 h at room temperature, wells were washed and then incubated with polyclonal antibody against mouse Il-6 conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. After washing the wells substrate solution was added and incubated for 30 min followed by stop solution. Optical density was measured at 450 nm. The Il-6 concentration was quantified using a standard curve created using the mouse Il-6 standards.

Detection of reactive electrophiles

We used 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) staining, which acquires fluorescent properties upon reacting with reactive electrophiles in an intracellular environment, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (Molecular Probes). Briefly, cell cultures were washed on day 3 with PBS and the H2DCFDA at 2 μM in PBS was added prior to incubation for 10 min, after which the cultures were washed with PBS and images of cells were obtained using fluorescent microscope (NIKON Eclipse, TE2000-S) with Spot software. The total number of DCF stained cells were quantified and plotted.

Statistical analysis

All data involving animal experimentation were collected by an investigator or technician blinded to the specific experimental group used. Data were expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3–5 for each condition). Student’s t-test was used and the P values ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant.

RESULTS

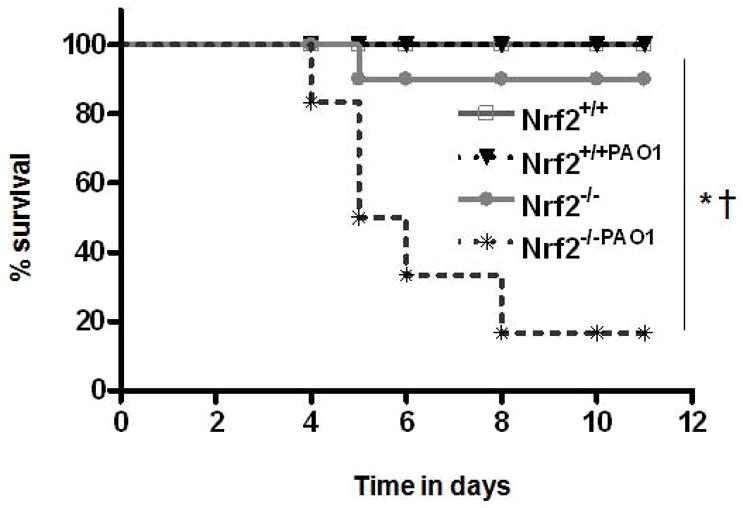

P. aeruginosa infection causes mortality in hyperoxia primed Nrf2-deficient mice

We have recently shown that a sub-lethal (48-h) hyperoxia exposure causes oxidative stress and persistent inflammation in Nrf2−/− mice (12). In order to test the effect of oxidative stress caused by Nrf2-deficieny on innate immunity, we inoculated wild-type (Nrf2+/+) and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to normoxia (room air) or hyperoxia by intratracheal instillation of 106 cfu of P. aeruginosa, an opportunistic human pathogen commonly associated with critically ill ALI patients (13, 15). After bacterial infection, mice were allowed to recover under normoxic condition. As shown in Fig. 1, 10 out of 12 (i.e. >80%) infected Nrf2−/− mice under hyperoxic stress died between 4 to 8 days. In contrast, 92% of infected Nrf2−/− mice exposed to normoxic condition survived up to 12 days. In contrast, 100% of the Nrf2+/+ mice under either normoxic or hyperoxic exposure survived the infection to the end point (12 days). These observations demonstrate that Nrf2 deficiency impairs the innate immunity and greatly enhances susceptibility to bacterial infection after hyperoxic insult.

Figure 1. Survival times of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice infected with P. aeruginosa following hyperoxic insult.

Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (n = 12/genotype) were exposed to room air or hyperoxia for 48 h and then infected with 106 cfu P. aeruginosa. Mice were allowed to recover under normoxic condition (room air). The survival times of mice were monitored every 6–12 h thereafter for several days as indicated. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype (n=5); † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− mice vs. Nrf2+/+ mice subjected to hyperoxia.

Nrf2-deficiency impairs lung innate immunity to P. aeruginosa after hyperoxia exposure

In order to determine the mechanisms by which Nrf2 mitigates bacterial infection after hyperoxic exposure, we infected the Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after sub-lethal (48-h) hyperoxia exposure with a lower (105 cfu) dose of P. aeruginosa given by intratracheal instillation. Some mice exposed to hyperoxia were allowed to recover under normoxia for 72 h and were then infected with bacteria. Mice were sacrificed at 4 h post-infection and lung histology as well as bacterial clearance was assessed as detailed in Methods. Although P. aeruginosa infection produced a moderate and comparable degree of lung inflammation in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice under nomoxia (Fig. 2A, left panel), we noticed a striking difference in the lung histology between these two genotypes after hyperoxia (middle panel) and recovery (right panel) (See supplemental data for 4x (Figure S1) and 10x pictures (Figure S2). P. aeruginosa infection caused extensive inflammatory cellular infiltration in the alveolar space of Nrf2−/− mice in the recovery period (right panel, bottom). In contrast, moderate cellular infiltration and intact alveolar structure was observed in the lungs of Nrf2+/+ mice (right panel, top).

Figure 2. Effects hyperoxia on lung histology and bacterial clearance in Nrf2−/− mice.

Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice were exposed to room air or hyperoxia and then infected with P. aeruginosa at a dose of 105 cfu for 4 h. One group of hyperoxia exposed mice were allowed to recover for 72 h (recovery) and then infected with P. aeruginosa. After 4 h post-infection, mice were killed and left lobes were fixed in formalin, while right lobes were lavaged with 1ml of PBS. (A) Histopathology of lungs of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice infected for 4 h showing signs of cellular infiltration and alveolar damage. (B) Bacterial burden in the lungs of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to room air (RA) hyperoxia (hyp) and under recovery (Rec). Graphs represent the number of cfu of bacteria remaining in the lung and in the BAL fluid, which were quantified as detailed in Methods. Each bar represents the mean value of five mice with SD. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− mice vs. Nrf2+/+ mice subjected to hyperoxia. (C and D) Lung histology and bacterial clearance of hyperoxia primed Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after 72 h infection. Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice were exposed to room air or hyperoxia and then infected with a dose of 106 cfu P. aeruginosa. After 72 h post-inoculum, mice were sacrificed and left lobes were fixed in formalin for histological analysis while the right lobes were used for BAL collection and bacterial colony counting. Histopathology of lungs of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice infected for 72 h, showing signs of cellular infiltration and alveolar damage (panel C). Graph represents the number of cfu bacteria remaining in the lung and in BAL fluid (panel D). Bars represent the mean values with SD. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype (n=5); † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− mice vs. Nrf2+/+ mice subjected to hyperoxia.

To determine whether Nrf2-deficiency alters bacterial clearance, we quantified total cfu present both in the lung tissue and BAL fluid after a 4 h post-infection (Fig. 2B). Approximately 75% of the 105 cfu P. aeruginosa was cleared in Nrf2+/+ mice and in Nrf2−/− mice under normoxia (compare bar 1 and bar 4). The bacterial clearance was modest in Nrf2+/+ mice under hyperoxia, as 85% of the total inoculum remained in the lung (bar 2). However, 70% of the 105 cfu was cleared in Nrf2+/+ mice, when infected 3 days post hyperoxia exposure (bar 3), in a manner similar to that of room air exposed control (open bars). In contrast, although ~70% of the 105 cfu was cleared in Nrf2−/− mice under normoxia (bar 4), the bacterial cfu increased to 175% of the original inoculum under hyperoixa (bar 5). Unlike the wild-type mice, the bacterial cfu in lungs of Nrf2−/− mice was increased to 200% of the inoculum (bar 5) when infected 72 h after recovery from hyperoxia (bar 6). Thus, the ability to clear bacterial infection was significantly suppressed in the Nrf2−/− mice at 4 h post-infection, leading to high pulmonary bacterial load compared to wild-type mice.

We further investigated the histological changes and kinetics of bacterial clearance by analyzing lung tissue and BAL fluid after a 72 h infection with 106 cfu (Fig. 2C). This infectious period, compared to 4 h-infection, caused severe cellular infiltration into alveolar spaces of hyperoxia exposed and recovered Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ mice (Fig. 2C, supplemental data for 4x (Figure S3) and 10x pictures (Figure S4). Similar to the 4 h infection, Nrf2+/+ mice under normoxia were able to clear more than 70% of the bacteria as assessed by the cfu present both in the lung and BAL fluid (Fig. 2D, bar 1). However, the high dose of bacteria in Nrf2−/− mice under normoxia caused bacterial out growth 72 h after infection (bar 4). These mice were defective at clearing bacteria and the number of bacteria rose to 125% of inoculum. Hyperoxia also inhibited bacterial clearance in Nrf2+/+ mice and 75% of the inoculum survived even after 72 h infection (bar 2), but the bacterial numbers were increased to 190% of inoculum in Nrf2−/− mice under hyperoxia (Fig. 2D, bar 5). The total cfu present in the lungs of hyperoxia-recovered Nrf2+/+ mice was nearly comparable to the total inocula (bar 3), whereas the bacterial numbers rose to 260% of the original inoculum in the Nrf2−/− mice under recovery (bar 6). These results suggest that the Nrf2-regulated transcriptional response is critical for clearing bacteria clearance following acute lung injury.

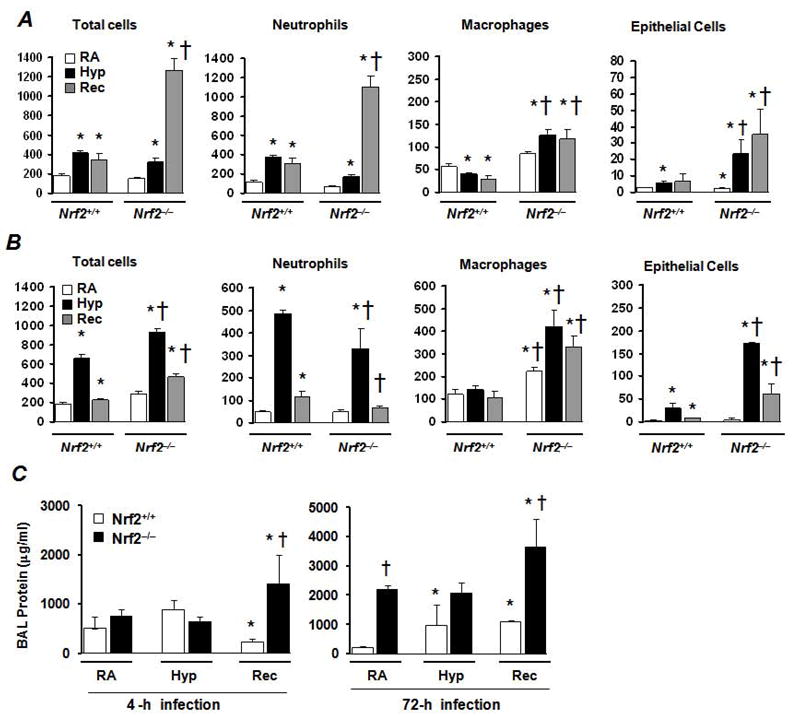

P. aeruginosa infection increases lung inflammation in Nrf2−/− mice under hyperoxia

It has been observed that an exaggerated inflammation occurs during secondary infections in injured lungs (16). To test the role of Nrf2 in controlling the inflammatory responses due to secondary infections after hyperoxia exposure, we next assessed bacteria–induced inflammation in lungs of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to either normoxia or hyperoxia as well as in mice undergoing recovery after hyperoxia. As a measure of lung inflammation, we quantified inflammatory cell accumulation in the BAL fluid at 4 h (Fig. 3A) and 72 h (Fig. 3B) post-infection. We observed striking differences in bacteria induced inflammatory cell accumulation in the BAL fluid between the two genotypes after hyperoxia and during recovery (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3A, at 4-h post-infection severe infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, as well as increased epithelial cell sloughing, were observed in Nrf2−/− mice exposed to hyperoxia and in the recovery period as compared to the corresponding Nrf2+/+ mice. A prolonged (72 h) infection period caused greater levels of macrophage accumulation and epithelial cell sloughing in the Nrf2−/− mice exposed to hyperoxia and in the recovery period as compared to the wild-type controls (Fig. 3B). However, as opposed to the 4 h, the 72 h infection did not cause a significant change in the numbers of neutrophils accumulated between these two genotypes of mice undergoing recovery. As a measure of lung injury, we quantified protein concentration in the BAL fluid of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice at 4 h (Fig. 3C, left panel) and 72 h (Fig. 3C, right panel) post-infection. We observed striking differences in bacteria induced protein accumulation in the BAL fluid of Nrf2−/− mice during recovery at 4-h post-infection (left panel, compare bar 6 and bar 5). At 72-h post-infection (right panel), increased level of protein accumulation was also observed in Nrf2−/− mice as compared to counterpart Nrf2+/+ mice.

Figure 3. Effects of hyperoxia on bacterial induced lung inflammation in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice.

Following exposure to room air or hyperoxia exposure, Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice were infected with P. aeruginosa at 105 (A) and 106 cfu (B) for 4 h and 72 h, respectively, as in Figure 2. The relative numbers of total cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells present in the BAL fluid of both genotypes are shown. (C) Protein concentration in the BAL fluids of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice at 4-h and 72-h post-infection with P. aeruginosa. Each bar represents the mean value with SD (n =3–4). *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− mice vs. Nrf2+/+ mice.

Hyperoxia induces persistent oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine expression in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages

Alveolar macrophages play key roles in clearing bacteria during infections (17). Therefore, we determined the levels of oxidative stress in alveolar macrophages obtained from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice immediately after exposure to hyperoxia, by staining with DCF reagent as detailed in Methods. As anticipated, there was no detectable level of DCF-staining present in alveolar macrophages obtained from room air exposed mice from either genotype (Fig. 4A, see supplemental data Figure S5 for color images). We found greater levels of DCF staining in alveolar macrophages isolated from both Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to hyperoxia (Fig. 4A middle). However, the DCF staining of alveolar macrophages was persistent in hyperoxia-exposed Nrf2−/− mice in recovery, but not in those from the Nrf2+/+ mice (Fig. 4A, right). The total number of DCF-positive alveolar macrophages obtained from the BAL fluid was quantified and relative expression levels of DCF-positive cells were shown in the graph (Fig. 4A). Approximately 80 percent of total BAL macrophages of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− genotypes showed positive DCF-staining following hyperoxia exposure. However, DCF-staining remained persisted in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages during recovery from hyperoxia (bar 6), whereas counterpart Nrf2+/+ alveolar macrophages showed very low or undetectable level of DCF- staining (bar 3) which was comparable to room air control group (bar 1). These results suggest that hyperoxia causes persistent oxidative stress in alveolar macrophages in the absence of Nrf2. To further correlate these results with cellular antioxidant status, we measured mRNA levels of Gclc, a classic transcriptional target of Nrf2, whose product is required for GSH biosynthesis. We found greater levels of Gclc expression in alveolar macrophages obtained from Nrf2+/+ mice exposed to hyperoxia, and the induction was persistent through the 72 h recovery compared to those of normoxic controls (Fig. 4B). The induction of Gclc following hyperoxic exposure was absent in alveolar macrophages isolated from Nrf2−/− mice, and somewhat decreased during hyperoxia and in the recovery phase.

Figure 4. Effects of hyperoxia on oxidative stress and inflammatory gene expression in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages.

(A) DCF staining of BAL macrophages collected from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to room air (left), 48 h hyperoxia (middle), and in recovery (right). Graph represents quantification of relative number of cells stained with DCF. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype and † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells. The expression levels of Gclc (B) and Il-1 and Il-6 (C) in macrophages obtained from the BAL fluid were analyzed using TaqMan real-time probes. The values represented are means with SD (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells subjected to hyperoxia. (D) ELISA measurement of Il-6 levels in the BAL fluids of Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ mice exposed to room air, 48 h hyperoxia, and during recovery. Data are means with SD (n = 4–5). *P < 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P < 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells.

We next examined whether these differential responses were due to production of different levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Analysis of the inflammatory cytokine expression in alveolar macrophages revealed a marked difference in the levels of Il-1 and Il-6 transcripts between Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after hyperoxia (Fig. 4C). The levels of Il-1 transcript decreased in alveolar macrophages after hyperoxia in both genotypes, and were elevated during recovery. However, the magnitude of Il-1 induction was 3-fold greater in Nrf2−/− macrophages during recovery compared to Nrf2−/− macrophages (Fig. 4C, compare bar 3 and bar 6). Il-6 mRNA expression was also increased by 20-fold in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages during the recovery, while it was markedly low in Nrf2+/+ alveolar macrophages. However, we found no significant differences in the expression of this cytokine between the alveolar macrophages of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after hyperoxic exposure. To determine whether increased levels of Il-6 mRNA expression in macrophages correlate with protein levels, we have analyzed Il-6 protein in the BAL fluid of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after hyperoxia and during recovery (Fig. 4D). We did not find significant change in the levels of Il-6 protein in BAL fluids of Nrf2+/+ mice after hyperoxia (bar 2) and during recovery (bar 3) compared to room air control (bar 1). In contrast, Il-6 protein levels were markedly increased in the BAL fluid of Nrf2−/− mice during recovery (Fig. 4D, bar 6) compared to room air (bar 4) and hyperoxia exposed groups (bar 5) as well as counterpart Nrf2+/+ mice (bar 3). These data demonstrate that hyperoxia induces persistent oxidative stress accompanied by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokine (Il-6 and Il-1) expression in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages during recovery.

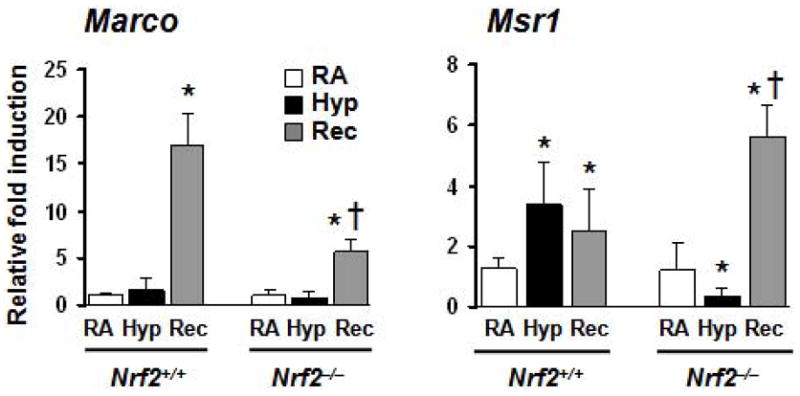

Scavenger receptor induction by hyperoxia is deregulated in Nrf2−/− macrophages

Because the macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO) and macrophage scavenger receptor (MSR1; also known as scavenger receptor SRA I) regulate phagocytosis (18, 19), we next measured their expression levels in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages obtained from hyperoxia-exposed and room air-recovered Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 5). While there was no significant difference in the expression of Marco transcripts after hyperoxia, this expression was increased significantly during recovery by 17-fold in Nrf2+/+ cells. However, the magnitude of this induction was significantly diminished (~5-fold) in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages (left panel). As shown in right panel, Msr1 expression was also significantly increased in Nrf2+/+ mice after hyperoxia (3.7-fold, bar 2), and during recovery (3-fold, bar 3). In contrast, Msr1 induction by hyperoxia was decreased Nrf2−/− mice as compared to room air exposed control (compare bar 4 and bar 5), but the expression of Msr1 was increased during recovery (bar 6) in Nrf2−/− mice.

Figure 5. The effects of hyperoxia on scavenger receptor expression in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages.

The mRNA expression levels of Marco (left panel) and Msr1 (right panel) in macrophages from room air, hyperoxia-exposed and recovered mice were determined using real-time PCR analysis. The values represented are means with SD. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells exposed to hyperoxia.

GSH supplementation augments the bactericidal activity of hyperoxia-exposed peritoneal macrophages from Nrf2−/− mice

We have previously shown that administration of GSH to hyperoxia exposed Nrf2−/− mice rescues the impaired resolution of lung injury and inflammation during recovery (12) as well as restores the proliferation of Nrf2−/− alveolar epithelial cells in vitro (10). In order to test whether glutathione supplementation rescues the bactericidal activity of Nrf2−/− macrophages, we isolated peritoneal macrophages from Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ mice following thioglycolate administration, and exposed them to hyperoxia ex vivo in the presence and absence of GSH-methyl ester for 24 h and then assessed their bactericidal activity (Fig. 6). The macrophages of Nrf2−/− mice were defective in bacterial killing compared to those of the Nrf2+/+ mice. Hyperoxia impaired the ability to kill P. aeruginosa in Nrf2−/− but not Nrf2+/+ macrophages (Fig. 6A). However, the reduction in the bactericidal activity of macrophages was more pronounced in Nrf2−/− cells. Supplementation of GSH restored the bactericidal capacity in normoxia- and hyperoxia-exposed Nrf2−/− mice macrophages to a level comparable to that of Nrf2+/+ mice.

Figure 6. The effects of hyperoxia exposure on bactericidal activity of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− peritoneal macrophages.

Peritoneal macrophages isolated from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice and supplemented without (open bars) or with GSH (filled bars) were exposed to hyperoxia for 24 h and then incubated with P. aeruginosa at 1:100 ratio for 60 min. (A) The cfu of the remaining bacteria were determined as described in Methods and bactericidal indices were calculated. † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells exposed to hyperoxia. § P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs Nrf2−/−GSH of the hyperoxia exposed experimental groups. The relative expression levels of Gclc (B) and Il-6 (C) transcripts in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− peritoneal macrophages exposed to room air (RA), hyperoxia (Hy), P. aeruginosa (PA) and combination of hyperoxia and P. aeruginosa (Hy+PA) supplemented without (open bars) and with GSH (filled bars) are shown. Each bar represents the average value with SD (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05 vs. room air control of the same genotype; † P ≤ 0.05, Nrf2−/− vs. Nrf2+/+ cells exposed to hyperoxia.

To determine whether a diminished level of antioxidant gene expression was associated with impaired bacterial killing, we assessed induction of Gclc, the rate limiting enzyme in GSH biosynthesis, in Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ alveolar macrophages immediately after hyperoxia and/or P. aeruginosa exposure. The Gclc expression in Nrf2+/+ cells was strongly induced ~30-fold and ~9-fold by P. aeruginosa and hyperoxia, respectively. However, the combined exposure had either a synergistic or additive effect on the induction levels (Fig. 6B). In contrast, hyperoxia and/or P. aeruginosa failed to stimulate the Gclc expression in both Nrf2−/− and Nrf2−/−GSH macrophages compared to untreated controls (Fig. 6B).

Since oxidative stress is known to induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines, we next measured the expression levels of Il-6 transcripts (Fig. 6C). Addition of P. aeruginosa to macrophages stimulated the Il-6 expression in control and hyperoxia exposed macrophages by 305- and 217-fold, respectively (Fig. 6C, left panel). Il-6 expression was increased 2.4 fold in Nrf2−/− cells compared to control macrophages. There was a robust increase in the levels of Il-6 in P. aeruginosa infected control (4700-fold) and hyperoxia-exposed (652-fold) Nrf2−/− macrophages. The induction of Il-6 decreased with GSH supplementation in P. aeruginosa infected control and hyperoxia-exposed Nrf2−/− macrophages.

DISCUSSION

Collectively, our present findings demonstrate that the Nrf2-regulated transcriptional response is critical in effectively mitigating bacteria-induced lung injury and inflammation as well as mortality in mice primed with a hyperoxic insult. While hyperoxia has been shown to impair the pulmonary innate immunity to bacterial infections (20–26), our study for the time establish a link between a dysfunctional Nrf2/ARE response and increased risk of opportunistic pulmonary bacterial infection during recovery from hyperoxic exposure. Overall, our findings likely have major clinical implications as bacterial infections can exacerbate preexisting lung injury and inflammation and, in some cases, cause death in critically ill patients receiving oxygen supplementation (13, 27). Importantly, several studies have shown an association between NRF2 promoter polymorphisms located at position −650 nt, −686 nt, and −684 nt and enhanced disease susceptibility (28–32). For example, we have previously shown that −650 NRF2 promoter polymorphism is associated with enhanced susceptibility to ALI in humans in a well-characterized trauma group at-risk for this syndrome (28). In separate studies, Arisawa et al reported that −650 and −686 polymorphisms associate with the development of gastric mucosal inflammation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection (29), while −686 and −684 were correlated with development of ulcerative colitis and gastric ulcers in humans (32). Based on these observations, we propose that either a deregulated NRF2 expression and/or a dysfunctional NRF2/ARE response may enhance susceptibility to opportunistic lung infections after an initial hyperoxic insult in vulnerable populations.

Pulmonary macrophages and neutrophils play key roles in clearing apoptotic and necrotic cells, as well as invading microbial pathogens, leading to a proper resolution of inflammation following toxin and oxidant exposures or lung infections (33–36). Previous studies have shown that peritoneal macrophages exposed to hyperoxia in vitro and alveolar macrophages isolated from mice exposed to hyperoxia exhibit impaired bacterial adherence, chemotaxis, phagocytosis and pathogen killing (20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 37). Impaired clearance of bacteria after hyperoxic insult in Nrf2−/− mice could be attributed to either a decline in the recruitment or impaired macrophage functions under our experimental conditions. However, despite the presence of high levels of macrophages, bacterial outgrowth in lungs of Nrf2−/− mice is remarkably higher than wild-type mice (Fig. 2), suggesting impairment of antibacterial effector function of Nrf2−/− macrophages. Our studies revealed that hyperoxia alone caused elevated levels of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine expression in Nrf2−/− alveolar macrophages during recovery (Fig. 4). Previous studies have shown, in agreement with our results, that exposure to particulate matter impairs macrophage effector functions in response to Streptococcus infection, which was associated with elevated levels of intracellular oxidative stress (38–40). Thus, it is likely that oxidative stress induced by hyperoxia, in the absence of a functional Nrf2-regulated ARE driven transcriptional response, might contribute to impairment of antibacterial function of alveolar macrophages in vivo, thereby resulting in lung bacterial burden and inflammation ultimately leading to death of the host.

Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines by Nrf2−/− peritoneal macrophages may promote the recruitment of other leukocytes thereby perpetuating inflammation and injury in response to bacterial infection. This notion is further supported by in vitro studies, as hyperoxia exposure diminished the ability of Nrf2−/− peritoneal macrophages to effectively clear bacterial infection, and enhanced expression of mediators of inflammation; however, GSH supplementation was able to rescue the impaired ability of the Nrf2−/− cells to clear bacteria and suppress the inflammatory cytokine expression (Fig. 6). Although defects in adherence, chemotaxis, phagocytosis or pathogen killing can impair the ability of macrophages to effectively eliminate bacteria, it is unclear whether lack of a functional Nrf2/ARE signaling cripples one or more steps of bacterial clearance in our experimental conditions. Nonetheless, our studies reveal that Nrf2/ARE signaling is critical to counteract the effects of hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress and also for effective macrophage antibacterial function, which otherwise would impair macrophage function and enhance bacteria-induced injury and inflammation. We have observed increased levels of lung neutrophils in Nrf2+/+ mice primed with hyperoxia, both after 4 h and 72 h of P. aeruginosa challenge compared to counterpart Nrf2−/− mice. Previous studies have shown that hyperoxia impairs the clearance of P. aeruginosa by decreasing the accumulation of neutrophils in lung tissue and BAL fluid by promoting their adherence to the endothelium (20). It is unclear whether apoptosis or enhanced adherence of neutrophils to endothelium contributes to lower levels of neutrophils in BAL fluid and lung tissue in Nrf2−/− mice.

Phagocytosis is an actin-dependent internalization process that requires the oxidation of actin by S-glutathionylation. S-glutathionylation of actin is essential for cell spreading and cytoskeletal reorganization and internalization of phagocytosed bacteria (41, 42). Reactive electrophiles generated during oxidant exposure consume protons in the phagosome, causing alkalinization of the phagosome and inhibition of acidic proteases (43). Although our results suggest that Nrf2-regulated, GSH-induced signaling plays an essential role in regulating bacterial clearance by macrophages, the exact mechanisms by which Nrf2-deficiency dampens the innate immunity following hyperoxic insult, as well as the means by which how GSH restores this defect in vivo, remain to be investigated.

Scavenger receptors are critical for clearance of the damaged cellular organelles by toxins and oxidants as well as dead cells (18). These receptors are also critical to effectively regulate macrophage antibacterial function. Macrophages recognize and bind foreign particles and bacteria with scavenger receptors, such as MARCO and MSR1 (or SRA I) (44–46). These receptors have been shown to attenuate oxidant- and toxin-induced lung inflammation by scavenging oxidized lipids and bacteria from lung lining fluids (18,19). Gene expression analysis revealed that both hyperoxia and P. aeruginosa strongly induce Marco and Msr1 expression in Nrf2+/+ macrophages, however, their induction is markedly lower in Nrf2−/− cells (Fig. 5). Previous studies have shown that Marco and Msr1 are critical for effectively dampening bacteria-induced lung inflammation. For example, genetic disruption of Marco in mice, like that of Nrf2, causes impaired ability to clear bacteria from lungs and increased lethality (47), while disruption of Msr1 increases susceptibility to oxidant induced lung inflammation (48, 49). Thus, it is likely that diminished levels of Marco and Msr1 expression at least in part contribute to impairment of the antibacterial function of Nrf2−/− macrophages. Although the mechanism by which hyperoxia and P. aeruginosa regulate expression of Marco and Msr1 is unclear, murine genomic sequence analysis revealed the presence of Nrf2-binding ARE/ARE-like sites in the promoter region of Marco, but not that of Msr1. Further studies are warranted to define whether Nrf2, directly through ARE or indirectly through ARE-regulated anti-oxidative response (GSH signaling), regulates Marco and Msr1 expression.

In summary, our studies demonstrate, for the first time, that the Nrf2-regulated transcriptional response is critical for the regulation of inflammation (especially macrophage accumulation) and in the maintenance of epithelial cell integrity during secondary microbial infection following initial injury. Since promoter polymorphisms of this transcription factor are associated with increased susceptibility to ALI and bacteria-induced inflammation in humans, our findings further support that targeting Nrf2 pathway may be a valuable therapeutic strategy in controlling lung inflammation associated with bacterial infection in critically ill patients subjected to oxygen supplementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: Funded by National Institute of Health grants HL66109 and ES11863 (SPR), HL049441 (PH), SCCOR P50 HL073994 (SPR and PH), and CA94076 (TWK) and [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (SRK).

We thank both Pathology Core of the ALI SCCOR and Microarray Core supported by Hopkins-NIEHS center for utilizing their facilities and services in the present study.

References

- 1.Crapo JD. Morphologic changes in pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Annu Rev Physiol. 1986;48:721–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crapo JD, Barry BE, Foscue HA, Shelburne J. Structural and biochemical changes in rat lungs occurring during exposures to lethal and adaptive doses of oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:123–143. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagano A, Barazzone-Argiroffo C. Alveolar cell death in hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:405–416. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chabot F, Mitchell JA, Gutteridge JM, Evans TW. Reactive oxygen species in acute lung injury. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:745–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comhair SA, Erzurum SC. Antioxidant responses to oxidant-mediated lung diseases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L246–255. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00491.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB. Regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression mediated by the antioxidant response element. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:233–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho HY, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR. Nrf2 defends the lung from Oxidative Stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:76–87. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho HY, Jedlicka AE, Reddy SPM, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Role of NRF2 in Protection Against Hyperoxic Lung Injury in Mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:175–182. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.2.4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho HY, Reddy SP, Yamamoto M, Kleeberger SR. The transcription factor NRF2 protects against pulmonary fibrosis. Faseb J. 2004;18:1258–1260. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1127fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy NM, Kleeberger SR, Cho HY, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Biswal S, Reddy SP. Deficiency in Nrf2-GSH Signaling Impairs Type II Cell Growth and Enhances Sensitivity to Oxidants. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:3–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0004RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy NM, Kleeberger SR, Bream JH, Fallon PG, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Reddy SP. Genetic disruption of the Nrf2 compromises cell-cycle progression by impairing GSH-induced redox signaling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5821–5832. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy NM, Kleeberger SR, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Hassoun PM, Reddy SP. Disruption of Nrf2 impairs the resolution of hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury and inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2009;182:7264–7271. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:867–903. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2105078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey ME, Caiazza NC, O’Toole GA. Rhamnolipid surfactant production affects biofilm architecture in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1027–1036. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1027-1036.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS, Christman JW, Prince AS. Pathogen-host interactions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1209–1223. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1044SO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamee LA, Harmsen AG. Both influenza-induced neutrophil dysfunction and neutrophil-independent mechanisms contribute to increased susceptibility to a secondary Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6707–6721. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00789-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dockrell DH, Marriott HM, Prince LR, Ridger VC, Ince PG, Hellewell PG, Whyte MK. Alveolar macrophage apoptosis contributes to pneumococcal clearance in a resolving model of pulmonary infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:5380–5388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thakur SA, Hamilton RF, Jr, Holian A. Role of scavenger receptor a family in lung inflammation from exposure to environmental particles. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5:151–157. doi: 10.1080/15476910802085863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palecanda A, Kobzik L. Receptors for unopsonized particles: the role of alveolar macrophage scavenger receptors. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:589–595. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn MM, Smith LJ. The effects of hyperoxia on pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:676–681. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada RN, Vatter AE, Repine JE. Macrophage effector function in pulmonary oxygen toxicity: hyperoxia damages and stimulates alveolar macrophages to make and release chemotaxins for polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1984;35:373–383. doi: 10.1002/jlb.35.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suntres ZE, Omri A, Shek PN. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury: role of oxidative stress. Microb Pathog. 2002;32:27–34. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Reilly PJ, Hickman-Davis JM, Davis IC, Matalon S. Hyperoxia impairs antibacterial function of macrophages through effects on actin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:443–450. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0153OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tateda K, Deng JC, Moore TA, Newstead MW, Paine R, 3rd, Kobayashi N, Yamaguchi K, Standiford TJ. Hyperoxia mediates acute lung injury and increased lethality in murine Legionella pneumonia: the role of apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4209–4216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baleeiro CE, Wilcoxen SE, Morris SB, Standiford TJ, Paine R., 3rd Sublethal hyperoxia impairs pulmonary innate immunity. J Immunol. 2003;171:955–963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikuchi Y, Tateda K, Fuse ET, Matsumoto T, Gotoh N, Fukushima J, Takizawa H, Nagase T, Standiford TJ, Yamaguchi K. Hyperoxia exaggerates bacterial dissemination and lethality in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markowicz P, Wolff M, Djedaini K, Cohen Y, Chastre J, Delclaux C, Merrer J, Herman B, Veber B, Fontaine A, Dreyfuss D. Multicenter prospective study of ventilator-associated pneumonia during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. ARDS Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1942–1948. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9909122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzec JM, Christie JD, Reddy SP, Jedlicka AE, Vuong H, Lanken PN, Aplenc R, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto M, Cho HY, Kleeberger SR. Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. Faseb J. 2007;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7759com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Hasegawa S, Takagi T, Wang FY, Hirata I, Nakano H. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and promoter polymorphism of the Nrf2 gene in chronic gastritis. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Arima Y, Okubo M, Hirata I, Nakano H. The influence of promoter polymorphism of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 gene on the aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelium. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Okubo M, Sakata M, Wang FY, Hirata I, Nakano H. Nrf2 gene promoter polymorphism is associated with ulcerative colitis in a Japanese population. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:394–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Arima Y, Okubo M, Hirata I, Nakano H. Association between promoter polymorphisms of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 gene and peptic ulcer diseases. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:849–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marriott HM, Dockrell DH. The role of the macrophage in lung disease mediated by bacteria. Exp Lung Res. 2007;33:493–505. doi: 10.1080/01902140701756562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faurschou M, Borregaard N. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nauseef WM. How human neutrophils kill and degrade microbes: an integrated view. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:88–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rehm SR, Gross GN, Pierce AK. Early bacterial clearance from murine lungs. Species-dependent phagocyte response. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:194–199. doi: 10.1172/JCI109844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raffin TA, Simon LM, Braun D, Theodore J, Robin ED. Impairment of phagocytosis by moderate hyperoxia (40 to 60 per cent oxygen) in lung macrophages. Lab Invest. 1980;42:622–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou H, Kobzik L. Effect of concentrated ambient particles on macrophage phagocytosis and killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:460–465. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0293OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldsmith CA, Imrich A, Danaee H, Ning YY, Kobzik L. Analysis of air pollution particulate-mediated oxidant stress in alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1998;54:529–545. doi: 10.1080/009841098158683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker S, Soukup JM, Gallagher JE. Differential particulate air pollution induced oxidant stress in human granulocytes, monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Toxicol In Vitro. 2002;16:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(02)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalle-Donne I, Giustarini D, Rossi R, Colombo R, Milzani A. Reversible S-glutathionylation of Cys 374 regulates actin filament formation by inducing structural changes in the actin molecule. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiaschi T, Cozzi G, Raugei G, Formigli L, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Redox regulation of beta-actin during integrin-mediated cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22983–22991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahl M, Bauer AK, Arredouani M, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kleeberger SR, Kobzik L. Protection against inhaled oxidants through scavenging of oxidized lipids by macrophage receptors MARCO and SR-AI/II. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:757–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI29968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi H, Sakashita N, Okuma T, Terasaki Y, Tsujita K, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Nomori H, Kawasuji M, Takeya M. Class A scavenger receptor (CD204) attenuates hyperoxia-induced lung injury by reducing oxidative stress. J Pathol. 2007;212:38–46. doi: 10.1002/path.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Granucci F, Petralia F, Urbano M, Citterio S, Di Tota F, Santambrogio L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. The scavenger receptor MARCO mediates cytoskeleton rearrangements in dendritic cells and microglia. Blood. 2003;102:2940–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arredouani M, Yang Z, Ning Y, Qin G, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kobzik L. The scavenger receptor MARCO is required for lung defense against pneumococcal pneumonia and inhaled particles. J Exp Med. 2004;200:267–272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beamer CA, Holian A. Scavenger receptor class A type I/II (CD204) null mice fail to develop fibrosis following silica exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L186–195. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00474.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thakur SA, Beamer CA, Migliaccio CT, Holian A. Critical role of MARCO in crystalline silica-induced pulmonary inflammation. Toxicol Sci. 2009;108:462–471. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.