Abstract

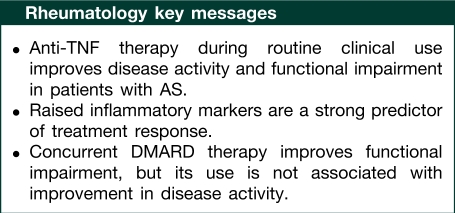

Objective. Few data exist on the use of anti-TNF drugs for AS during routine clinical use in the UK. This report describes an improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) after 6 months of therapy in 261 patients enrolled in a national prospective observational register.

Methods. The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) recruited patients starting anti-TNF therapy for AS between 2002 and 2006. Multivariable linear regression models were used to estimate the predictors of absolute improvement in BASDAI and BASFI at 6 months. Covariates included age, gender, disease duration, baseline BASDAI and BASFI, presence of raised inflammatory markers (defined as twice the upper limit of normal) and DMARD therapy.

Results. The cohort was young (median age 43 years) and 82% were males. Median baseline BASDAI was 7.6 and BASFI 7.9. At 6 months, the mean improvements in BASDAI and BASFI were 3.6 and 2.6 U, respectively; 52% reached a BASDAI50. Patients with raised inflammatory markers at the start of therapy had a 0.9-U (95% CI 0.2, 1.5) better improvement in BASDAI compared with those without. Lesser responses were seen in those with higher baseline BASFI scores. Women had a 1.1-U (95% CI 0.3, 2.0) greater improvement in BASFI at 6 months, as did those who were receiving concurrent DMARD therapy [0.9 U (95% CI 0.2, 1.7)].

Conclusions. The majority of patients receiving anti-TNF therapy for AS during routine care demonstrated an improvement in disease activity. Raised inflammatory markers at the start of therapy predicted a greater improvement in BASDAI, identifying a group of patients who may be more responsive to anti-TNF therapies, although the results were not confined to this group.

Keywords: Anti-TNF, Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab, Ankylosing spondylitis, Treatment response, Treatment effectiveness, Disability

Introduction

AS is an inflammatory disorder mainly affecting the axial skeleton, although peripheral joints and extra-articular tissue may also be involved [1]. The cytokine TNF-α is regarded as an important mediator in the disease process and raised levels of TNF have been found in the SI joints of patients with AS [2]. Anti-TNF has been used as a successful treatment in RA for several years and more recently was shown to be effective in AS [3–5]. There are currently three anti-TNF agents approved for the treatment of AS: infliximab and adalimumab, both mAbs directed against TNF, and etanercept (ETA), a soluble p75 TNF receptor fusion protein. Guidelines for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with AS in the UK were published in July 2004 by the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) [6]. These guidelines state that treatment with anti-TNF agents may be appropriate for those patients who (i) satisfy the modified New York criteria for the diagnosis of AS [7], (ii) have failed conventional treatment with two or more NSAIDs, and (iii) have active disease as defined by a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [8] score ⩾4 and spinal pain score ⩾4 cm, measured on a 10-cm visual analogue scale. The recommended doses are etanercept 25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly, infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2, 6 weeks and 6–8 weekly thereafter, adalimumab 40 mg s.c. every 2 weeks. Unlike RA [9], there are no specific recommendations regarding co-therapy with MTX.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown all three anti-TNF agents to be efficacious. However, patient selection in clinical trials is not always representative of prescribing guidelines and clinical practice in individual countries. Data from observational studies of response to anti-TNF treatment in AS have previously been published [10–15], although robust conclusions are often prevented by the small sample sizes of these studies. A large, open-label Phase IIIb trial of adalimumab identified that factors including younger age, higher CRP concentration and HLA-B27 positivity were associated with good clinical response, defined as either a 50% improvement in the BASDAI (BASDAI50), a 40% improvement in the Assessments of SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria (ASAS40) or ASAS partial remission [16]. Few studies have looked specifically at the factors associated with improvements in function.

The aims of this study were (i) to evaluate the effectiveness of anti-TNF drugs within a UK cohort of AS patients receiving anti-TNF therapy during routine clinical care by assessing changes in measurements of disease activity and functional ability 6 months after starting treatment; and (ii) to identify factors, measured at the start of treatment, which are associated with improvements in disease activity and function.

Patients and methods

Study population

The subjects for this analysis are participants in a large prospective observational study, the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR). This register was established in 2001, with the primary aim of monitoring the long-term safety of biologic agents in RA [17]. However, between 2002 and 2006, the register also captured data on a small cohort of biologic naïve AS patients starting treatment with their first anti-TNF agent.

Data

Upon initiation of anti-TNF treatment, the patient’s rheumatologist or rheumatology nurse specialist completes a baseline questionnaire and forwards this to the BSRBR. This includes details on demographics, disease activity (28-active joint count, ESR or CRP), previous and current anti-rheumatic therapy and comorbidity. Follow-up questionnaires are completed every 6 months and details of changes to anti-rheumatic therapies, disease activity and functional status are captured. As the BSRBR was initially designed to collect information on patients with RA, early questionnaires did not include specific AS disease activity measures. In September 2003, the baseline questionnaire was amended to include the BASDAI and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) [18]. To reduce the amount of missing data, physicians who had recruited patients before this date were contacted to forward results of missing BASDAIs and BASFIs, where available.

Analysis

Analysis was performed using Stata version 9.2 (Stata, 2006, College Station, TX, USA). Baseline characteristics were compared among the three anti-TNF agents using non-parametric descriptive statistics. The primary outcome measure was absolute change in BASDAI between baseline and 6-month assessment for the whole cohort. Secondary measures included the absolute change in BASFI between baseline and 6-month assessment. To represent UK prescribing guidelines, the final measurement assessed the proportion of patients who achieved at least 50% improvement in BASDAI (BASDAI50) after 6 months of treatment, the benchmark by which UK physicians are advised to make decisions on response [6].

Factors associated with the absolute change in BASDAI and BASFI in the first 6 months were modelled using linear regression. Covariates included age, gender, disease duration, baseline BASDAI and BASFI, the presence of raised inflammatory markers (defined as ESR > 25 mm/h and/or CRP > 20 mg/l), concurrent DMARD therapy, smoking status, year when anti-TNF therapy was started and the anti-TNF drug used. Factors with significance at P ⩽0.2 in univariate models were entered into a multivariable model. Similarly, a multivariable logistic regression model was developed to identify factors associated with achieving a BASDAI50 response at 6 months, using the same covariates.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the BSRBR was obtained from the Central Office for Research Ethics Committees of the UK National Health Service. All patients gave written informed consent.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Till July 2007, 261 patients with AS were registered with the BSRBR and had completed both a baseline and 6-month BASDAI. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. As would be expected in a cohort of patients with AS, subjects were young with a male to female ratio of 4 : 1. The median disease duration was 13 years. The median BASDAI was 7.6 [interquartile range (IQR) 6.4–8.6] and the median BASFI was 7.9 (IQR 6.2–8.9), indicating severe disease. In general, subjects treated with each of the three anti-TNF agents were very similar, although more patients starting infliximab or adalimumab were receiving concurrent DMARDs. Patients receiving infliximab also tended towards longer disease duration, although this did not reach statistical significance. The median dose of infliximab was 4.9 (IQR 4.0–5.0) mg/kg, although 25% of the cohort was receiving 3 mg/kg, the licensed starting dose for RA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Anti-TNF treatment | All | Etanercept | Infliximab | Adalimumab | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 261 | 148 (57) | 93 (36) | 20 (7) | |

| Age, years | 43 (37–51) | 43 (35–51) | 43 (37–51) | 44 (39–56) | 0.70 |

| Male, n (%) | 213 (82) | 124 (84) | 70 (75) | 19 (95) | 0.07 |

| Disease duration, years | 13 (6–21) | 12 (6–20) | 15 (6–25) | 15 (10–19) | 0.40 |

| BASDAI, U | 7.6 (6.4–8.6) | 7.7 (6.6–8.6) | 7.5 (5.6–8.5) | 7.6 (6.7–8.3) | 0.31 |

| BASFI, U | 7.9 (6.2–8.9) | 8.0 (6.0–8.9) | 7.7 (6.0–8.9) | 7.9 (6.9–8.6) | 0.77 |

| ESR, mm/h | 31 (14–63) | 30 (14–67) | 34 (14–62) | 27 (11–51) | 0.47 |

| CRP, mg/l | 23 (9–55) | 26 (8–57) | 23 (12–49) | 16 (9–26) | 0.56 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 85 (33) | 45 (30) | 32 (35) | 8 (40) | |

| Previously | 81 (31) | 43 (29) | 34 (37) | 4 (20) | 0.27 |

| Currently | 94 (36) | 60 (41) | 26 (28) | 8 (40) | |

| DMARD at start of anti-TNF therapy, n (%) | 116 (44) | 55 (37) | 50 (54) | 11 (55) | 0.03 |

| MTX | 90 (35) | 40 (27) | 40 (43) | 10 (50) | 0.01 |

| SSZ | 37 (14) | 19 (13) | 16 (17) | 2 (10) | 0.55 |

| >1 DMARD | 21 (8) | 9 (6) | 10 (11) | 2 (10) | 0.11 |

| NSAID treatment, n (%) | 189 (72) | 106 (72) | 69 (74) | 14 (70) | 0.88 |

| Steroid treatment, n (%) | 38 (15) | 22 (15) | 13 (14) | 3 (15) | 0.98 |

Values are given as median (IQR), unless otherwise specified.

Response

The mean improvement in BASDAI after 6 months was 3.6 U and 52% of patients achieved a BASDAI50 (Table 2). The mean improvement in BASFI after 6 months was 2.6 U. Improvement in both ESR [mean improvement 27.3 mm/h (95% CI 23.4, 31.3)] and CRP level [mean improvement 25.3 mg/l (95% CI 18.2, 32.5)] was also observed at 6 months.

Table 2.

Response to anti-TNF treatment at 6 months

| Anti-TNF treatment | All | Etanercept | Infliximab | Adalimumab | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 261 | 148 | 93 | 20 | |

| BASDAI at start of therapy, mean (s.d.) | 7.3 (1.8) | 7.4 (1.7) | 7.0 (2.0) | 7.3 (1.7) | 0.31 |

| BASDAI at 6 months, mean (s.d.) | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.3 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.4) | 4.7 (3.2) | 0.01 |

| Unadjusted change in BASDAI, mean (95% CI) | − 3.6 (− 3.9, − 3.3) | − 4.1 (− 4.6, − 3.8) | − 2.9 (− 3.4, − 2.4) | − 2.5 (− 3.6, − 1.4) | 0.0002 |

| Achieving BASDAI50 response, n (%) | 136 (52) | 93 (64) | 36 (39) | 7 (35) | P < 0.01 |

| BASFI at the start of therapy, mean (s.d.) | 7.3 (2.2) | 7.4 (2.0) | 7.1 (2.4) | 7.6 (1.7) | 0.77 |

| BASFI at 6 months, mean (s.d.) | 4.6 (2.8) | 4.4 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.7) | 3.8 (3.2) | 0.09 |

| Unadjusted change in BASFI, mean (95% CI) | − 2.6 (− 3.0, − 2.2) | − 3.1 (− 3.6, − 2.7) | − 1.7 (− 2.3, − 1.1) | − 3.4 (− 4.9, − 1.9) | 0.0028 |

| ESR at the start of therapy, mean (s.d.), mm/h | 39.4 (29.3) | 40.6 (31.2) | 39.6 (27.6) | 30.9 (22.6) | 0.21 |

| ESR after 6 months of therapy, mean (s.d.), mm/h | 13.1 (14.8) | 13.0 (14.8) | 13.8 (15.9) | 10.3 (5.9) | 0.19 |

| Unadjusted change in ESR, mean (95% CI), mm/h | − 27.3 (− 31.3, − 23.4) | − 27.5 (− 33.1, − 21.8) | − 26.9 (− 33.2, − 20.7) | − 28.3 (− 37.5, − 19.1) | 0.48 |

| CRP at the start of therapy, mean (s.d.), mg/l | 35.3 (35.1) | 36.9 (35.12) | 35.5 (36.6) | 24.7 (26.4) | 0.36 |

| CRP after 6 months of therapy, mean (s.d.), mg/l | 11.9 (22.2) | 11.4 (24.6) | 12.9 (20.2) | 10.7 (15.0) | 0.23 |

| Unadjusted change in CRP, mean (95% CI), mg/l | − 25.3 (− 32.5, − 18.2) | − 25.1 (− 35.8, − 14.4) | − 29.0 (− 40.0, − 18.0) | − 8.6 (− 20.6, + 3.3) | 0.46 |

Results of the multivariable linear regression analysis of factors associated with change in BASDAI at 6 months are shown in Table 3. The strongest predictors were baseline BASDAI score, with a 0.69 U better improvement for each unit increase in baseline BASDAI score, and the presence of raised inflammatory markers (ESR and/or CRP) at the start of therapy, with a 0.89 greater improvement among those with raised baseline indices. However, patients with the higher baseline BASFI scores demonstrated less improvement in BASDAI. The use of concurrent DMARDs was not significantly associated with absolute improvements in BASDAI.

Table 3.

BASDAI change at 6 months—linear regression models

| Covariates | Univariate, coefficient (95% CI) | Multivariate,a coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, decades | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07) | 0.02 (− 0.01, 0.05) |

| Female | − 0.48 (− 1.28, 0.32) | − 0.32 (− 1.08, 0.44) |

| Disease duration | 0.02 (− 0.01, 0.05) | − 0.01 (− 0.04, 0.03) |

| Baseline BASDAI (per unit increase) | − 0.51 (− 0.67, − 0.35) | − 0.69 (− 0.90, − 0.48) |

| Baseline BASFI (per unit increase) | − 0.12 (− 0.28, 0.03) | 0.26 (0.08, 0.45) |

| Raised inflammatory markers | − 0.71 (− 1.35, − 0.07) | − 0.89 (− 1.53, − 0.24) |

| NSAID treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.25 (− 0.95, 0.01) | – |

| MTX treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.05 (− 0.70, 0.61) | – |

| Any DMARD treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.12 (− 0.75, 0.51) | – |

| Steroid treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.16 (− 1.05, 0.72) | – |

| Smoking—never | Reference | – |

| Smoking—previous | 0.46 (− 0.31, 1.24) | – |

| Smoking—current | − 0.46 (− 1.21, 0.28) | – |

aMultivariable analysis adjusted additionally for calendar year of starting therapy and anti-TNF drug.

Similar results were found in a logistic regression analysis, looking at predictors of a 50% improvement in BASDAI (BASDAI50) (Table 4). In addition, patients were more likely to achieve a BASDAI50 when anti-TNF drugs were taken in combination with DMARDs. When the effects of concurrent DMARD therapy on BASDAI50 were stratified by anti-TNF agent, concurrent DMARDs appeared to only be important in patients receiving infliximab (50% response in co-therapy vs 26% monotherapy; P = 0.016). Small numbers prevented comparison between the anti-TNF drugs.

Table 4.

BASDAI50 response at 6 months—logistic regression models

| Covariates | Univariate, OR (95% CI) | Multivariate,a OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, decades | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) |

| Female | 1.20 (0.64, 2.26) | 1.25 (0.58, 2.69) |

| Disease duration | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) |

| Baseline BASDAI (per unit increase) | 1.09 (0.95, 1.24) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.62) |

| Baseline BASFI (per unit increase) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.03) | 0.78 (0.64, 0.99) |

| Raised inflammatory markers | 1.40 (0.84, 2.32) | 2.02 (1.05, 3.87) |

| NSAID treatment at baseline (yes/no) | 1.24 (0.72, 2.13) | – |

| MTX treatment at baseline (yes/no)b | 1.48 (0.89, 2.49) | 2.23 (1.15, 4.52) |

| Any DMARD treatment at baseline (yes/no)b | 1.56 (0.95, 2.55) | 2.15 (1.11, 4.15) |

| Steroid treatment at baseline (yes/no) | 1.01 (0.51, 2.00) | – |

| Smoking—never | Reference | Reference |

| Smoking—previous | 0.56 (0.30, 1.03) | 0.84 (0.39, 1.84) |

| Smoking—current | 1.04 (0.58, 1.88) | 1.34 (0.63, 2.86) |

aMultivariable analysis, adjusted additionally for calendar year of starting therapy and anti-TNF agent. bMultivariate model run twice: once with MTX and then again with any DMARD as covariates.

Different factors were associated with an improvement in BASFI at 6 months (Table 5). At baseline, the median baseline BASFI in males was 7.9 (IQR 6.3–8.9) and in females 7.7 (IQR 6.1–9.2). The median baseline BASFI in patients not on concurrent DMARDs was 7.9 (IQR 6.4–8.9) and in those receiving DMARDs 7.6 (IQR 5.9–8.7). In a multivariate model, the strongest independent predictors of improvement in BASFI were being female, higher baseline BASFI and concurrent DMARD use, all favouring a greater improvement in BASFI. Improvements in BASFI were not related to baseline BASDAI.

Table 5.

BASFI change at 6 months—linear regression models

| Covariates | Univariate, coefficient (95% CI) | Multivariate,a coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, decades | 0.03 (− 0.01, 0.06) | 0.02 (− 0.01, 0.06) |

| Female | − 0.83 (− 1.75, 0.09) | − 1.11 (− 1.96, − 0.26) |

| Disease duration | 0.03 (− 0.00, 0.07) | 0.03 (− 0.01, 0.07) |

| Baseline BASDAI (per unit increase) | − 0.22 (− 0.42, − 0.03) | 0.10 (− 0.14, 0.34) |

| Baseline BASFI (per unit increase) | − 0.35 (− 0.52, − 0.17) | − 0.34 (− 0.57, − 0.12) |

| Raised inflammatory markers | − 0.64 (− 1.42, 0.14) | − 0.50 (− 1.23, 0.23) |

| NSAID treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.36 (− 1.18, 0.46) | – |

| MTX treatment at baseline (yes/no)b | − 0.23 (− 1.06, 0.61) | −0.69 (− 1.48, 0.09) |

| DMARD treatment at baseline (yes/no)b | − 0.50 (− 1.26, 0.26) | − 0.94 (− 1.65, −0.23) |

| Steroid treatment at baseline (yes/no) | − 0.10 (− 1.13, 0.94) | – |

| Smoking—never | Reference | Reference |

| Smoking—previous | 0.58 (− 0.34, 1.49) | 0.34 (− 0.54, 1.22) |

| Smoking—current | − 0.82 (− 1.69, 0.05) | − 0.48 (− 1.32, 0.35) |

aMultivariable analysis, adjusted additionally for calendar year of starting therapy and anti-TNF therapy. bMultivariate model run twice: once with MTX and then again with any DMARD as covariates.

Discussion

This study evaluated the short-term effectiveness of anti-TNF in AS. The results are in agreement with the results from RCTs, indicating that anti-TNF therapy is an effective treatment option for patients with AS. Both the BASDAI and BASFI scores improved after 6 months of treatment, and more than half of the subjects achieved a BASDAI50 response.

Unlike the RCTs for anti-TNF drugs in AS, this study evaluated treatment of patients within the context of UK prescribing guidelines and enrolled many patients who could have been excluded from previous trials, for reasons including concurrent DMARD therapy or comorbidities. However, the BSRBR was not initially designed for analysis of effectiveness of anti-TNF drugs in AS patients. The register was adapted to collect further disease activity measures on AS patients and, therefore, may have excluded patients in whom BASDAI and BASFI were not collected by the treating physician. This exclusion may have threatened the external validity of our results. Although the baseline characteristics of the analysed cohort were generally in agreement with other published cohorts of AS patients, more patients were treated concurrently with DMARDs, in this study, than found in previous studies. It is not clear whether this is a reflection of exclusions from clinical trials or of differences in management within the UK. Finally, we did not have detailed data on non-biologic anti-rheumatic drug doses, such as NSAIDS or steroids, past the first visit and, therefore, are unable to assess the impact of these therapies on the results.

The strongest predictors of improvement in disease activity were raised inflammatory markers at the start of therapy and the higher baseline levels of disease activity, the latter of which may represent regression to the mean, whereas a higher BASFI score was associated with a lesser response. In our study, improvement in disease activity was not associated with age at the start of therapy or disease duration. A smaller observational study (n = 99) of infliximab- and etanercept-treated AS patients found that raised CRP, raised baseline BASDAI and lower baseline BASFI were predictive of achieving a BASDAI50 after 12 weeks of treatment [12]. Another study of 22 patients receiving infliximab found that those achieving an ASAS20 response at 1 year had higher CRP at baseline than non-responders [11], and that CRP did not correlate with BASDAI score at baseline. Further analysis of data collected during a Phase III clinical trial of ETA [19] and a Phase IIIb trial of adalimumab [16] found similar results.

In the BSRBR, ∼65% of subjects had raised inflammatory markers at baseline, and this was predictive of greater improvement in BASDAI score at 6 months. It has previously been found that ESR and CRP do not comprehensively represent the disease process in AS [20] and are not currently included in the BSR guidelines for prescribing anti-TNF in AS [6]. Although the effect of raised inflammatory markers was greater than that of baseline BASDAI score in predicting response, the decision to initiate anti-TNF therapy in AS should not be based solely on inflammatory markers, as 47% of the subjects without raised inflammatory markers at baseline achieved a BASDAI50 response. Although inflammatory markers may not correlate with disease severity, they may reflect an increased activity of cytokine-mediated inflammatory cells that will respond to anti-TNF therapy. Therefore, raised inflammatory markers may identify a group of AS patients with active and reversible disease, as opposed to long-standing chronic damage. Another possible explanation for this finding is that increased ESR and CRP may correlate with peripheral arthritis and extra-articular involvement in patients with AS. While the role of peripheral symptoms was not examined in this study, the beneficial action of anti-TNF drugs outside the axial skeleton may be responsible for the observed improvements in both BASDAI and BASFI scores.

Subjects with higher BASFI score at the start of therapy were less likely to see an improvement in BASDAI after 6 months. Similar results have previously been found in AS, where lower BASFI predicted a BASDAI50 response [12], and in RA, where lower HAQ scores were associated with response and remission [21]. Interestingly, a small study in PsA found that BASFI scores correlated more with FM signs and symptoms and fatigue than with radiological spinal involvement [22], suggesting that higher BASFI scores may also reflect long-term damage, chronic pain and other disability, which would be less responsive to anti-TNF therapy. This point aside, we still observed significant improvements in BASFI in this study.

Nearly 50% of patients in this study were receiving concurrent DMARDs, primarily MTX. Unfortunately, it was not known why these patients were receiving concurrent DMARDs (i.e. for peripheral arthritis or because of the benefits of co-prescription with anti-TNF seen in RA [23, 24]). DMARD use was not strongly associated with absolute change in BASDAI but was associated with achieving a BASDAI50 response, likely indicating that patients were more likely to cross the BASDAI50 threshold if they were receiving concurrent DMARD. A Norwegian study [15] did not find MTX to be a predictor of drug survival in AS, unlike their findings in both RA and PsA, suggesting that the effects of concurrent MTX on disease activity in patients with AS may be different.

This is the first study to identify predictors of improvement in function, measured using the BASFI. Unlike disease activity, we found a strong association between gender and improvement in function, with a significantly greater improvement in women. Concurrent DMARDs were also found to be a significant predictor of improvement in function, more so than that seen for BASDAI.

Although it was not the aim of this study to directly compare the different anti-TNF drugs, we did observe some differences. Small numbers in some groups prevented further adjustment in the analysis and therefore, this finding should be interpreted with some caution. Although it is difficult to compare results between clinical trials, a difference in efficacy between the three drugs was not suggested from the results of the major RCTs of anti-TNF in AS [3–5], with all studies finding an ASAS20 response in ∼60% of patients. It is not clear why one drug should perform better during ‘real world’ use. However, in this study, patients were not randomized to their anti-TNF therapies, and factors that may have influenced the physicians’ decision to treat may also have influenced the patient’s response. Perhaps, most importantly, all drugs were not equally available throughout the study period; etanercept was not available between 2001 and 2003 due to a worldwide shortage and adalimumab was not available until 2004. During the early years of this study, more patients were receiving infliximab as their first anti-TNF agent. These earliest patients were likely to be those with the most severe disease and, therefore, may have had a different response from those recruited later, although an analysis that restricted the patients to those recruited after 2003 found similar results. In addition, only 70% of subjects treated with infliximab were receiving the recommended dose of 5 mg/kg, with 25% receiving the dose of 3 mg/kg recommended in RA. Nonetheless, the influence of unmeasured confounders on this differential response cannot be discounted based on the results of this observational study and further observations are warranted.

Conclusions

Anti-TNF therapy is very effective in AS, with improvement in both disease activity and functional scores after 6 months of therapy. While study design prevents definitive conclusions, the results of this study suggest predictors of response. Baseline-raised ESR or CRP may identify a group of patients who are more responsive to anti-TNF therapy. Concurrent DMARD treatment was not found to be a significant predictor of improvement in disease activity, but was associated with improvement in function. Further assessment of observational datasets beyond 6 months is warranted to study the benefits of these agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the enthusiastic collaboration of all consultant rheumatologists and their specialist nurses in the UK in providing the data. In addition, we acknowledge the support from Dr Ian Griffiths (Past) and Prof. David Isenberg (Current), Chairs of the BSRBR Management Committee, Prof. Gabriel Panayi, Prof. David G. I. Scott, Dr Andrew Bamji and Dr Deborah Bax, Presidents of the BSR during the period of data collection, for their active role in enabling the Register to undertake its tasks and to Samantha Peters (CEO of the BSR), Mervyn Hogg, Nia Taylor and members of the BSRBR Scientific Steering Committee. We also acknowledge the seminal role of the BSR Clinical Affairs Committee for establishing the national biologic guidelines and recommendations for such a Register. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the substantial contribution of Andy Tracey and Katie McGrother in database design and manipulation and Prof. Alan Silman in his prior role as a principal investigator of the BSRBR.

The BSR commissioned the BSRBR as a UK-wide national project to investigate the safety of biologic agents in routine medical practice. D.P.M.S. and K.H. are principal investigators on the BSRBR. The BSR receives restricted income from UK pharmaceutical companies, presently Abbott Laboratories, Biovitrum, Schering Plough, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and Roche. This income finances a wholly separate contract between the BSR and the University of Manchester who provide and run the BSRBR data collection, management and analysis services. The principal investigators and their team have full academic freedom and are able to work independently of pharmaceutical industry influence. All decisions concerning analyses, interpretation and publication are made autonomously of any industrial contribution. Members of the Manchester team, BSR trustees, committee members and staff completed an annual declaration in relation to conflicts of interest. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Funding: This project is supported by grants from the British Society for Rheumatology and the UK Arthritis Research Campaign. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the British Society for Rheumatology.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francois RJ, Neure L, Sieper J, et al. Immunohistological examination of open sacroiliac biopsies of patients with ankylosing spondylitis: detection of tumour necrosis factor alpha in two patients with early disease and transforming growth factor beta in three more advanced cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:713–20. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis JC, Jr, Van der HD, Braun J, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3230–6. doi: 10.1002/art.11325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der HD, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT) Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:582–91. doi: 10.1002/art.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der HD, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2136–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keat A, Barkham N, Bhalla A, et al. BSR guidelines for prescribing TNF-alpha blockers in adults with ankylosing spondylitis. Report of a working party of the British Society for Rheumatology. Rheumatology. 2005;44:939–47. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der LS, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledingham J, Deighton C. Update on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNFalpha blockers in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (update of previous guidelines of April 2001) Rheumatology. 2005;44:157–63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikas SN, Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, et al. Infliximab treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: an observational study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:940–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone MA, Payne U, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. Cytokine correlates of clinical response patterns to infliximab treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:84–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.006916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, et al. Prediction of a major clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:665–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konttinen L, Tuompo R, Uusitalo T, et al. Anti-TNF therapy in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: the Finnish experience. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1693–700. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gadsby K, Deighton C. Characteristics and treatment responses of patients satisfying the BSR guidelines for anti-TNF in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:439–41. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heiberg MS, Koldingsnes W, Mikkelsen K, et al. The comparative one-year performance of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: results from a longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:234–40. doi: 10.1002/art.23333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudwaleit M, Claudepierre P, Wordsworth P, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and predictors of good clinical response in 1250 patients treated with adalimumab for active ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:801–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silman A, Symmons D, Scott DG, et al. British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(Suppl. 2):ii28–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis JC, Jr, van der Heijde DM, Dougados M, et al. Baseline factors that influence ASAS 20 response in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1751–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruof J, Stucki G. Validity aspects of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in ankylosing spondylitis: a literature review. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:966–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyrich KL, Watson KD, Silman AJ, et al. Predictors of response to anti-TNF-alpha therapy among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1558–65. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brockbank JE, Schimmer J, Schentag C, et al. Spinal disease assessment in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [Abstract] J Rheumatol. 2001;28:62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1552–63. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyrich KL, Symmons DP, Watson KD, et al. Comparison of the response to infliximab or etanercept monotherapy with the response to cotherapy with methotrexate or another disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1786–94. doi: 10.1002/art.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]