Abstract

Rottlerin, a polyphenol isolated from Mallotus Philippinensis, has been recently used as a selective inhibitor of PKC δ, although it can inhibit many kinases and has several biological effects. Among them, we recently found that Rottlerin inhibits the Nuclear Factor κB (NFκB), activated by either phorbol esters or H2O2. Because of the redox sensitivity of NFκB and on the basis of Rottlerin antioxidant property, we hypothesized that Rottlerin could prevent NFκB activation acting as a free radicals scavenger, as other natural polyphenols. The current study confirms the antioxidant property of Rottlerin against the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) in vitro and against oxidative stress induced by H2O2 and by menadione in culture cells. We also demonstrate that Rottlerin prevents TNFα-dependent NFκB activation in MCF-7 cells and in HT-29 cells transfected with the NFκB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC, suggesting that Rottlerin can inhibit NFκB via several pathways and in several cell types.

1. Introduction

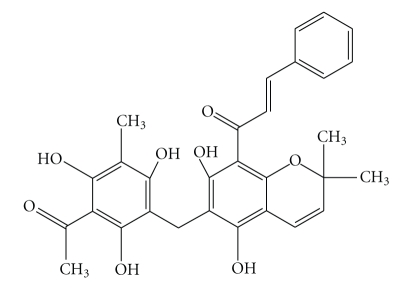

Rottlerin (also called mallotoxin or kamala) is a pigmented plant product isolated from MallotusPhilippinensis (Figure 1), used in India in ancient times as a remedy for tapeworm [1–3].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Rottlerin.

Since 1994, Rottlerin has been used as a PKCδ inhibitor based on in vitro studies that have shown that the IC50 for PKCδ was 3–6 μM compared to 30–100 μM for the other PKC isozymes [4], although the selectivity of Rottlerin in inhibiting PKC δ isoform has been recently questioned [5].

Several phloroglucinol derivatives, which are similar to Rottlerin in structure, have been demonstrated to have antiinflammatory and antiallergic properties [6, 7].

Moreover, Rottlerin can target mitochondria, interfering in the respiratory chain as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation [8], and activates the large conductance voltage and Ca++ activated K+ channel (BK) in human vascular smooth muscle; its use has been patented (patent WO/2006/060196) in the therapy of hypertension and related disorders [9].

Our laboratory showed for the first time that Rottlerin can suppress NFκB activation induced by either phorbol ester or H2O2, in MCF-7 cells and in HaCaT keratinocytes, respectively, in a PKC-independent way [10, 11]. Rottlerin is a pleiotropic inhibitor, able to inhibit the activity of a number of unrelated kinases, such as AKT/PKB and calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMKs) I-III [12, 13], two known upstream mediators of the NFκB activation process [14–19].

Although the underlying molecular mechanisms have not been yet investigated in details Rottlerin interference in the NFκB activation process was likely achieved, in MCF-7 cells, through inhibition of CaMKII, without involvement of the AKT/PKB pathway [10].

The transcription factor NFκB consists of p50 and p65 heterodimer, which is retained in the cytoplasm by masking nuclear localization signal (NLS) by the inhibitor IκBα. Upon activation, IκBα kinase (IKK) phosphorylates IκBα, promotes its ubiquitination and degradation, thus allowing p50-p65 to translocate to the nucleus, bind to its consensus sequence, and induce transcription of genes essential for cell proliferation and survival [20]. Consistently, Rottlerin inhibition of NFκB caused downregulation of cyclin D1 and growth arrest in both MCF-7 and in HaCaT cells [10, 11].

Because NFκB can be activated by a number of signaling molecules [21], we performed further experiments to support the idea that Rottlerin inhibits NFκB in different cell types and under different stimuli.

One interesting characteristic of NFκB is its extreme sensitivity to cellular redox state [22]. Since many agents activating NFκB are modulated by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) or by pro-oxidants, we wondered whether the inhibitory effects of Rottlerin, previously observed by us, could be also due to its antioxidant potential. Rottlerin, indeed, is a 5,7-dihydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-methyl-5-acetylbenzyl)-8-cinnamoyl-l,2-chromene and contains five phenolic hydroxyl groups that might likely act as hydrogen donors in the scavenging of free radicals in analogy with other polyphenols with documented antioxidant properties. An unexhaustive list of compounds, structurally related to Rottlerin, with antioxidant activity and NFκB inhibitory properties comprises Drummondins [23], Flavonoids [24], Resveratrol [25], Genistein [26, 27], Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate [28], and Curcumin [29].

Although it could have been deduced from the Rottlerin structure (known at least since 1994), only recently antioxidant properties of Rottlerin have been started to be described [30].

In the current paper, we demonstrate that Rottlerin has antioxidant properties and that the observed inhibitory effect on NFκB might be the result of Rottlerin hydrogen donating ability and free radical scavenger activity, in addition to its biological inhibition of signaling molecules. We also provide evidence that Rottlerin inhibits NFκB activation in MCF-7 and HT-29 cells and transcriptional activity in cells transfected with the NFκB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Minimum Essential Medium (MEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), Na-Pyruvate and L-glutamine and 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH), and menadione were purchased from Sigma (Milan, Italy), dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR-123) from Invitrogen, geneticin (G418 sulfate) from Alexis (San Diego, CA), Rottlerin from Calbiochem (Milan, Italy).

2.2. Cells and Culture Conditions

MCF-7 and TH-29 cells were purchased by Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia e dell'Emilia-Romagna, Brescia, Italy. MCF-7 cells were grown in humidified atmosphere (95% air/ 5% CO2) at 37°C in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 10% FBS, Na-Pyruvate (1 mM), and antibiotics. HT-29 cells were grown in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS, glutamine (2 mM), and antibiotics. After reaching subconfluence, cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 24 hr and then subjected to treatments in 2.5% FBS.

2.3. Cell Treatments

MCF-7 and HT-29 cells, pretreated with or without 20 μM Rottlerin for 30 min, were stimulated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 4 hr. As to concern the vitamin E samples, 24 hr preincubation time with 50 μM α-tocopherol (dissolved in DMSO at the final concentration in the cells of 0.1%) was selected on the basis of uptake experiments performed on cells (data not shown).

2.4. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA assay was performed as previous described by Valacchi et al. 2005 [31]. MCF-7 and HT-29 cells were plated on 100-mm dishes (7.5 × 105 cells/dish) and treated as described above. Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and dishes placed on dry ice/ethanol. Cells were lysed in 500 μl/dish buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM leupeptin) and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes. After incubation for 10 min on ice, Nonidet P-40 (final concentration 0.02%) was added, and suspensions were passed six times through a 26.5G needle to optimize cell lysis. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation for 2 min at 10,000 rpm, and supernatant (cytoplasmic extract) fractions were collected. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM leupeptin), incubated for 30 min on ice, and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm at 4°C to obtain clear supernatant fractions (nuclear extract). NFκB consensus oligonucleotide (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′), NFκB mutant oligonucleotide (5′-AGT TGA GGC GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′), and NF-IL6 (consensus) (nonspecific competitor - 5′-GGAGAGATTGCCTGAC-GTCAGAGAGGCA-3′) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were labeled with digoxygenin (Dig) using a DIG Genius gel shift kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) and incubated overnight at 5°C with nuclear extract (20 μg of protein). The complexes were electrophoresed (0.5 Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, 150 V for 2 hr at room temperature) on Novex 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and electroblotted (400 mA for 1 hr) in a sandwich procedure onto nitrocellulose (protein) and nylon (oligonucleotide) membranes. The Dig-labeled oligonucleotide was detected by anti-Dig alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Fab fragments and enhanced chemiluminescence. The p50 subunit of NFκB on the nitrocellulose membrane was probed by rabbit anti-NFκB (p50) antibody and detected by ECL Plus.

2.5. N,N-diphenyl-N-picrylhydrzyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Activity

To evaluate the anti-oxidant activity of Rottlerin, the model of scavenging the stable free radical DPPH by hydrogen donating compounds was used.

As stock solutions, 20 μM DPPH (A) and 10 μM Rottlerin (B), were prepared in absolute ethanol and mixed by adding increasing volumes of the Rottlerin solution to that of DPPH in a final volume of 3 ml to obtain DPPH/Rottlerin molar ratios 10 : 1, 4 : 1, and 2 : 1. The reaction mixtures were shaken vigorously and kept in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance of the remaining DPPH was determined at 516 nm by UV/Vis Kontron 941 spectrophotometer.

For electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, the same DPPH/Rottlerin solutions were transferred to glass capillary tubes and then placed in the EPR cavity of a Varian E4 ESR spectrometer for spectral measurements.

2.6. ROS Measurement by FACS Analysis

Serum starved MCF-7 cells were pretreated with Rottlerin (5 and 20 μM) for 1 hr. The cells were loaded with 10 μM DHR-123 for 15 minutes, washed by Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), and treated by the oxidative stress inducer, menadione (100 μM), or H2O2 (100 μM) for 30 min in HBSS. The reaction was stopped by cooling on ice for 1 min, and the cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, excitation: 488 nm laser, emission: 530/30 nm). The level of ROS was indicated by median of DHR-123 fluorescence. Debris and dead cells were discriminated from the analysis using FSC versus SSC gating.

2.7. Luciferase Reporter Construct and Stable HT-29 Cell Transfection

The reporter construct pBIIX-LUC was kindly donated by Dr. Kalle Saksela (Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Tampere, Finland). The NF-κB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC was constructed by inserting a synthetic fragment with two copies of the sequence ACA GAG GGG ACT TTC CGA GAG separated by four nucleotides (ATCT) in front of the mouse fos promoter in plasmid pfLUC [18].

The reporter plasmid was cotransfected with pSV2neo neomycin-resistance plasmid into HT-29 (ATCC) cells using electroporation (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA). Briefly, approximately 1 × 107 cells were mixed with 20 μg of reporter plasmid and 2 μg of pSV2neo plasmid, and electroporated (275 V, 950 μF, 2x pulse). Subsequently, the cells were seeded on a 100 × 20 mm dish (TPP) with a feeder of HT-29 cells treated with mitomycin-C. Neomycin-resistant clones were selected in 300 μg/mL of geneticin. The clones containing the reporter plasmid were confirmed by luciferase activity assay.

2.8. HT-29 Cell Treatment and Luciferase Activity Assay

Stably transfected cells were seeded in 12-well plates and treated, 24 hr later, with Rottlerin for 30 min followed by TNFα (10 ng/mL) for 4 hr. After the treatment, cells were rinsed with PBS and then lysed with 100 μl of reagent (Luciferase Assay System; Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Fifty μl of the extracts was mixed with 50 μl of luciferase substrate, and luminescence was quantified by luminometer.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student's t-test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

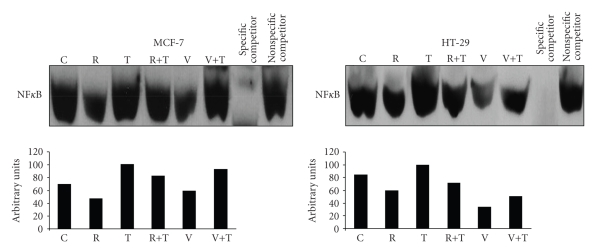

3.1. Rottlerin Inhibits TNFα-Induced NFκB Binding Activity in MCF-7 and HT-29 Cells

As shown in Figure 2, nuclear extracts from nonactivated MCF-7 and HT-29 cells (C) contained a basal or constitutive NFκB/DNA binding activity which was not affected by 20 μM Rottlerin treatment (R) nor by Vitamin E supplementation (V). Vitamin E was chosen as control since it is a well-known liposoluble antioxidant with the ability to inhibit NFκB. Treatment with 10 ng/ml TNFα (T) caused an elevated level of NFκB/DNA binding and the pretreatment of cells with Rottlerin or Vitamin E (T+R and T+V) inhibited TNFα-induced NFκB/DNA binding. The unlabeled NFκB consensus oligomer was used as the specific competitor and unlabeled NF-IL6 consensus oligomer as the nonspecific competitor.

Figure 2.

Rottlerin inhibits TNFα-induced NF-κB/DNA binding activities in MCF-7 and HT-29 cells. Cells were pretreated with Rottlerin (20 μM) or with Vitamin E (50 μM) with subsequent stimulation with TNFα (10 ng/mL) for 4 hr. Nuclear extracts (20 μg) were used to determine NF-B DNA binding activities by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using DIG-labled oligonucleotide containing NFκB element. The unlabeled NFκB consensus oligomer was used as the specific competitor and unlabeled NF-L6 consensus oligomer as the nonspecific competitor. Bottom panel shows the bands quantification of a representative blot. Complexes were visualized by chemiluminescence. Lanes: C, control; R, Rottlerin; T, TNFα; R+T; Rottlerin and TNFα; V, Vitamin E; V+T, Vitamin E and TNFα.

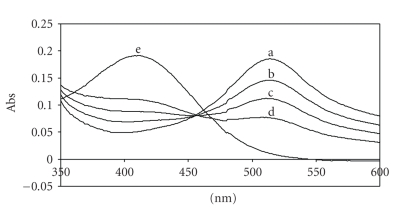

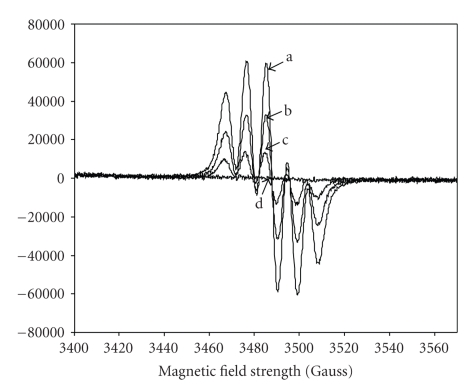

3.2. Antioxidant Activity of Rottlerin: Reaction with DPPH

In the case of the UV measurements, the DPPH and Rottlerin spectra do not overlap and the complete disappearance of the typical absorption of DPPH at 514 nm was observed when equal volume of the DPPH and Rottlerin solutions, A and B, respectively, were mixed (Figure 3). Similar results were obtained by EPR, which directly measures the free radical concentration; by mixing the two solutions into the EPR cavity, the typical EPR signal of DPPH disappeared when equal volumes of the reagents solutions were mixed, that is in a 2 : 1 molar ratio (Figur 4), because two molecules of DPPH are reduced by one molecule of Rottlerin.

Figure 3.

UV spectra of DPPH/Rottlerin solutions in absolute ethanol. (a) 20 μM DPPH ethanol solution (A); (b) spectrum of the mixture DPPH/Rottlerin obtained by mixing 2.5 ml of solution A with 0.5 ml of solution B (10 : 1 molar ratio); (c) 2.0 ml of solution A with 1 ml of solution B (4 : 1 molar ratio); (d) 1.5 ml of solution A with 1.5 ml of solution B (2 : 1 molar ratio); (e) spectrum of 10 μM Rottlerin ethanol solution (B).

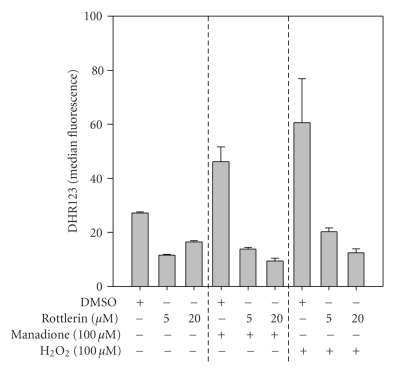

3.3. ROS Scavenging Activity of Rottlerin

As shown in Figure 5, both 5 and 20 μM Rottlerin significantly decreases MCF-7 basal ROS levels and largely prevent ROS generated by a 30-min treatment with either 100 μM H2O2 or 100 μM menadione.

Figure 5.

Rottlerin prevents both basal and induced intracellular production of H2O2. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 5 and 20 μM Rottlerin for 1 hr and loaded by H2O2-specific fluorescent probe DHR-123. Cells were treated with menadione (100 μM) and hydrogen peroxide (100 μM) for 30 min and analyzed using flow cytometry.

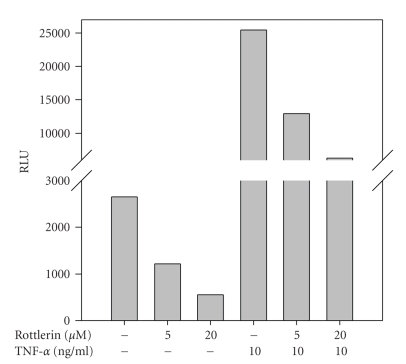

3.4. Effect of Rottlerin on NFκB Activation in HT-29 Transfected Cells

As shown in Figure 6, Rottlerin pretreatment for 30 min prevented activation of NFκB in a dose-dependent manner, both basal and after a 4 hr TNFα treatment in HT-29 cells transfected with the NFκB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC.

Figure 6.

Effect of Rottlerin on NFκB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity in HT-29 transfected cells. HT-29 cells, stably transfected with the NFκB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC, were pretreated for 30 min with 5 and 20 μM Rottlerin and then treated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 4 hr, before luciferase activity measurement. Data are the mean value ± SD of four independent experiments.

These results confirm that Rottlerin is a general inhibitor of NFκB nuclear migration and transcriptional activity.

4. Discussion

DPPH is a stable free radical, which is widely used to test the hydrogen donation of antioxidants [33]. Recently, the ability of Rottlerin to scavenge DPPH in comparison to other phenolic phytochemicals has been described. Empirically established concentrations of phytochemicals and DPPH showed that the Rottlerin scavenging ability was lower than that of resveratrol and genistein, higher than that of quercetin and epigallocatechin gallate, and roughly of the same order of that of curcumin [30].

In the present study, in order to further evaluate the hydrogen donation power of Rottlerin, we reacted one molecule of Rottlerin with two molecules of DPPH and followed the reaction by UV measurement and EPR spectroscopy (Figures 2 and 3). This last reaction is thermodynamically supported by the fact that the Bond Dissociation Enthalpy of the N-H group of the reduced DPPH is 80 Kcal/mol [34] and that of the O-H group of Vit-E is 77.9 Kcal/mol [35]. On the basis of this data it may be assumed that the hydrogen donation power of Rottlerin is of the same order of that of Vit-E, which is recognized like the best antioxidant for lipid systems [36].

The radical scavenging ability of polyphenols depends mainly on the positioning of the O-H groups rather than on their number [37], and this could be evident in Rottlerin, which possesses five phenolic O-H all conjugated to the same −CH2− group. This may suggest a higher antioxidant activity than that of the two frequently used ROS scavengers, namely, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylatedhydroxytoluene (BHT), which show BDEs of 81.1 and 79.1 Kcal/mol, respectively [38].

Because DPPH is an artificial radical and may not reproduce the in vivo situation, we also tested the Rottlerin antioxidant properties on cultured cells. According to the DPPH radical-reducing activity and its fast reactivity, Rottlerin neutralized hydrogen peroxide added to the cells and prevents free radicals generation (Figure 4). These finding are consistent with our previous report showing that Rottlerin quickly inhibited NFκB activation triggered by hydrogen peroxide in HaCaT keratinocytes [11] and are in accordance with the study by Longpre and Loo [30], showing that 20 μM Rottlerin prevented deoxycholate-induced ROS generation in HCT-116 cells.

Figure 4.

EPR spectra of DPPH /Rottlerin solutions in absolute ethanol. (a) 20 μM DPPH ethanol solution (A); (b), (c), and (d) correspond to the (b), (c), and (d) solutions of Figure 2. All spectra were recorded in the same experimental conditions.

Rottlerin-mediated inhibition of NFκB is not restricted to PMA [10] and hydrogen peroxide [11] because it also blunts TNFα-mediated NFκB activation. The current study indeed showed that NFκB nuclear migration and transcriptional activity, both basal and after stimulation by TNFα, are strongly inhibited by the drug in native MCF-7 cells and in HT-29 cells, and in HT-29 transfected with the NFκB-driven plasmid pBIIX-LUC, (2). Our results also parallel with a study by Zhang et al. where has been shown that Rottlerin inhibits NFκB activation in MCF7 sensitized cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis [39].

Taking in account the current results and previous data on PMA-stimulated MCF-7 cells [10] and H2O2-stimulated-HaCaT cells [11], it can be safely stated that Rottlerin is a general inhibitor of NFκB regardless of the activation pathway (PMA, oxidative stress or TNFα) and the cell type (MCF-7, HaCaT, HT-29 cells).

By integrating these findings, we conclude that the inhibitory effect of Rottlerin on NFκB is likely the result of a convergent double activity, free radical scavenging, and inhibition of key molecules, such as CaMKII [10] and/or PKC [40, 41] involved in the NFκB activation process.

Activation of NFκB is regulated by a bewildering number of signaling pathways, the contribution of which, in particular the cascade that mediates oxidative stress-induced NFκB, is not always known in detail. The only target common to the several positive or negative signals to NFκB is the IKK complex, but this, representing the final converging step of the different cascades, does not give information on the upstream mediators.

It is likely that Rottlerin acts at a step in which all the stimuli used (PMA, H2O2, menadione, TNFα) converge in the signal transduction pathway leading to NFκB activation.

It has been reported that 100 μM Resveratrol blocks NFκB activation through inhibition of the upstream PKC δ/PKD cascade in HeLa cells [41]. Since Rottlerin, at doses between 5 and 20 μM, is a PKCδ inhibitor, we initially thought that the Resveratrol's mechanism of action could explain also the Rottlerin effects on NFκB in MCF-7 cells. However, a preliminary experiment showed that 20 μM Rottlerin did not inhibit PMA-stimulated PKD phosphorylation on Ser 744 and Ser 748 (unpublished observation), indicating that Resveratrol and Rottlerin, although both are antioxidant with similar potency [30] and PKC δ inhibitors, act with different mechanisms in NFκB inhibition.

As far as the Rottlerin antioxidant effect is concerned, the interference of other natural antioxidants in the NFκB activation process has been already described. For example, mangiferin, a natural polyphenol with antioxidant properties, and melatonin, another potent antioxidant, block TNF-induced NFκB activation [42, 43].

In closing, the antioxidant effect of Rottlerin surely plays a main role in the NFκB activation process triggered by PMA or H2O2 or menadione or TNFα, but further studies will be necessary to establish the relative contribution of the two (chemical and biological) mechanisms and to clarify whether they act in parallel or in interdependent ways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. K. Saksela for kindly providing the reporter construct pBIIX-LUC. This work was supported by project Grants from the Italian Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR) (programma rientro cervelli V.G.), research projects Grants from “Fondazione Monte dei Paschi Siena” (2008) and Grants no. 204/07/0834, no. 310/07/0961 of the Czech Science Foundation and by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Grants no. AV0Z50040507 and AV0Z50040702.

References

- 1.Gupta SS, Verma P, Hishikar K. Purgative and anthelmintic effects of Mallotus philippinensis in rats against tape worm. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1984;28(1):63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava MC, Singh SW, Tewari JP. Anthelmintic activity of Mallotus philippinensis-kambila powder. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1967;55(7):746–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhtar MS, Ahmad I. Comparative efficacy of Mallotus philippinensis fruit (Kamala) or Nilzan® drug against gastrointestinal cestodes in Beetal goats. Small Ruminant Research. 1992;8(1-2):121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gschwendt M, Muller H-J, Kielbassa K, et al. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;199(1):93–98. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin: an inappropriate and ineffective inhibitor of PKCδ. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2007;28(9):453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daikonya A, Katsuki S, Wu J-B, Kitanaka S. Anti-allergic agents from natural sources (4): anti-allergic activity of new phloroglucinol derivatives from Mallotus philippensis (Euphorbiaceae) Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2002;50(12):1566–1569. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii R, Horie M, Saito K, Arisawa M, Kitanaka S. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression via suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation by Mallotus japonicus phloroglucinol derivatives. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1620(1–3):108–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin is a mitochondrial uncoupler that decreases cellular ATP levels and indirectly blocks protein kinase Cδ tyrosine phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(41):37986–37992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zakharov SI, Morrow JP, Liu G, Yang L, Marx SO. Activation of the BK (SLO1) potassium channel by mallotoxin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(35):30882–30887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torricelli C, Fortino V, Capurro E, et al. Rottlerin inhibits the nuclear factor κB/cyclin-D1 cascade in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Life Sciences. 2008;82(11-12):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valacchi G, Pecorelli A, Mencarelli M, et al. Rottlerin: a multifaced regulator of keratinocyte cell cycle. Experimental Dermatology. 2009;18(6):516–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochemical Journal. 2000;351(1):95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho SI, Koketsu M, Ishihara H, et al. Novel compounds, ‘1,3-selenazine derivatives’ as specific inhibitors of eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1475(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(00)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-κB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires tie Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401(6748):82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouyang W, Li J, Ma Q, Huang C. Essential roles of PI-3K/Akt/IKKβ/NFκB pathway in cyclin D1 induction by arsenite in JB6 Cl41 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):864–873. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes K, Edin S, Antonsson A, Grundström T. Calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates T cell receptor/CD3-and phorbol ester-induced activation of IκB kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(38):36008–36013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J, Krushel LA, Crossin KL. NF-κB activation by N-CAM and cytokines in astrocytes is regulated by multiple protein kinases and redox modulation. Glia. 2001;33(1):45–56. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(20010101)33:1<45::aid-glia1005>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howe CJ, Lahair MM, Maxwell JA, et al. Participation of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinases in hydrogen peroxide-induced IκB phosphorylation in human T lymphocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(34):30469–30476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra S, Mishra JP, Gee K, McManus DC, LaCasse EC, Kumar A. Distinct role of calmodulin and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II in lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated suppression of apoptosis and antiapoptotic c-IAP2 gene expression in human monocytic cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(45):37536–37546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banno T, Gazel A, Blumenberg M. Pathway-specific profiling identifies the NF-κB-dependent tumor necrosis factor α-regulated genes in epidermal keratinocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(19):18973–18980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viatour P, Merville M-P, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2005;30(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoonbroodt S, Piette J. Oxidative stress interference with the nuclear factor-κB activation pathways. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2000;60(8):1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayasuriya H, Mcchesney JD, Swanson SM, Pezzuto JM. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of rottlerin-type compounds from Hypericum drummondii. Journal of Natural Products. 1989;52(2):325–331. doi: 10.1021/np50062a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakagami H, Jiang Y, Kusama K, et al. Induction of apoptosis by flavones, flavonols (3-hydroxyflavones) and isoprenoid-substituted flavonoids in human oral tumor cell lines. Anticancer Research. 2000;20(1A):271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subbaramaiah K, Chung WJ, Michaluart P, et al. Resveratrol inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription and activity in phorbol ester-treated human mammary epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(34):21875–21882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Ahmed F, Air S, Philip PA, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of nuclear factor κB by soy isoflavone genistein contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in human cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65(15):6934–6942. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Ahmed F, Air S, Philip PA, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Erratum: inactivation of nuclear factor κB by soy isoflavone genistein contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents in human cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65(23):p. 11228. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad N, Gupta S, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate differentially modulates nuclear factor κB in cancer cells versus normal cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2000;376(2):338–346. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhandapani KM, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Curcumin suppresses growth and chemoresistance of human glioblastoma cells via AP-1 and NFκB transcription factors. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;102(2):522–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longpre JM, Loo G. Protection of human colon epithelial cells against deoxycholate by rottlerin. Apoptosis. 2008;13(9):1162–1171. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valacchi G, Pagnin E, Phung A, et al. Inhibition of NFκB activation and IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells by acrolein. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2005;7(1-2):25–31. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molyneux P. The use of stable free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for estimating antioxidant activity. Songklanakarin Journal of Science & Technology. 2004;26(2):211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saksela K, Baltimore D. Negative regulation of immunoglobulin kappa light-chain gene transcription by a short sequence homologous to the murine B1 repetitive element. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(6):3698–3705. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo Y-R. Handbook of Dissociation Energies in Organic Compounds. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borges dos Santos R-M, Martinho Simoes J-A. Energetic of the OH bond in phenol and substituted phenols: a critical evaluation data. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1998;27(3):707–739. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowry VW, Ingold KU. The unexpected role of vitamin E (α-tocopherol) in the peroxidation of human low-density lipoprotein. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1999;32(1):27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thavasi V, Leong LP, Bettens RPA. Investigation of the influence of hydroxy groups on the radical scavenging ability of polyphenols. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2006;110(14):4918–4923. doi: 10.1021/jp057315r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denisov E. Handbook of Antioxidants: Bond Dissociation Energies, Rate Constants, Activation Energies and Enthalpies of Reactions. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Liu N, Zhang J, Liu S, Liu Y, Zheng D. PKCδ protects human breast tumor MCF-7 cells against tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2005;96(3):522–532. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontny E, Kurowska M, Szczepanska K, Maslinski W. Rottlerin, a PKC isozyme-selective inhibitor, affects signaling events and cytokine production in human monocytes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2000;67(2):249–258. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storz P, Döppler H, Toker A. Activation loop phosphorylation controls protein kinase D-dependent activation of nuclear factor κB. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;66(4):870–879. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarkar A, Sreenivasan Y, Ramesh GT, Manna SK. β-D-glucoside suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced activation of nuclear transcription factor κB but potentiates apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(32):33768–33781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasaki M, Jordan P, Joh T, et al. Melatonin reduces TNF-a induced expression of MAdCAM-1 via inhibition of NF-κB. BMC Gastroenterology. 2002;2, article 9 doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]