Abstract

The channels mediating most of the somatodendritic A-type K+ current in neurons are thought to be ternary complexes of Kv4 pore-forming subunits and two types of auxiliary subunits, the K+ channel interacting proteins (KChIPs) and dipeptidyl-peptidase-like (DPPL) proteins. The channels expressed in heterologous expression systems by mixtures of Kv4.2, KChIP1 and DPP6-S resemble in many properties the A-type current in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons and cerebellar granule cells, neurons with prominent A-type K+ currents. However, the native currents have faster kinetics. Moreover, the A-type currents in neurons in intermediary layers of the superior colliculus have even faster inactivating rates. We have characterized a new DPP6 spliced isoform, DPP6-E, that produces in heterologous cells ternary Kv4 channels with very fast kinetics. DPP6-E is selectively expressed in a few neuronal populations in brain including cerebellar granule neurons, hippocampal pyramidal cells and neurons in intermediary layers of the superior colliculus. The effects of DPP6-E explain past discrepancies between reconstituted and native Kv4 channels in some neurons, and contributes to the diversity of A-type K+ currents in neurons.

Keywords: A-type potassium channel, Inactivation, DPPX, DPP6

Potassium channel proteins of the Kv4 subfamily are the primary or pore-forming subunits of the ion channels mediating most of the subthreshold-operating somatodendritic transient or A-type K+ currents (ISAs) in neurons [23,32] reviewed in [22]. These currents have fundamental roles in neuronal function. They contribute to subthreshold excitability, spike repolarization, the control of the frequency of repetitive firing, signal processing in dendrites and spike timing-dependent plasticity [5–7,9,10,14,15,20,21,28,36]. In spinal cord dorsal horn neurons, the ISA is a critical target of modulation of neuronal excitability and nociceptive behavior [10]. Moreover, a truncation in the gene encoding Kv4.2 (KCND2) has been identified in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) [33], highlighting the relevance of ISAs in epilepsy. These roles of ISAs rely on the precise voltage-dependence and kinetic properties of the underlying K+ channels. These properties in turn are determined by the molecular components of channel complexes.

Recent studies have led to the view that native Kv4 channels in CNS neurons are complexes composed of Kv4 pore-forming subunits (Kv4.2 and/or Kv4.3) and at least two distinct types of auxiliary subunits: the Kv channel interacting proteins (KChIPs) and the dipeptidyl-peptidase-like (DPPL) proteins DPP6 (also known as DPPX) and DPP10 (also known as DPPY) [1,11,13,22,26,29,40]. KChIPs and DPPLs control the trafficking and stability of channel complexes in the plasma membrane and have major effects on the voltage-dependence and kinetics of the channels.

This hypothesis is strongly supported by evidence that the currents expressed in heterologous cells by ternary Kv4–KChIP–DPPL complexes resemble native currents in neurons more closely than the currents expressed by Kv4 subunits alone [11,26]. A recent study explored this similarity in detail by directly comparing the properties of the ISA in cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) and the currents in heterologous mammalian cells expressing the Kv4–KChIP–DPP6 ternary complex obtained under the same recording conditions [2]. This investigation showed that, although the shape of the curves describing channel properties was the same for the native and the reconstituted systems, there remain quantitative differences. Specifically, the native currents were faster than the reconstituted currents. Moreover, the rate of inactivation of the ISA is even faster in other neurons, including neocortical pyramidal cells and several types of neurons in intermediary layers of the superior colliculus than it is in CGNs [4,18,31]. This could be explained by differences in membrane composition or posttranslational modifications of one or more of the channel components. However, Jerng et al. [11] recently suggested that an alternatively spliced DPP10 isoform (DPP10-A), which is expressed in neocortex and produces faster inactivation than other DPP10 isoforms and all known DPP6 versions, could explain the faster inactivation of the ISA in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Yet, the DPP10 gene is not expressed in CGNs or in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, which inactivate at rates similar to CGNs [9]. These neuronal populations express the DPP6 gene [25,40].

Here we report the cloning of a novel DPP6 alternatively spliced isoform, DPP6-E, that when co-expressed with Kv4.2 and KChIP subunits produces currents with very fast kinetics in mammalian heterologous cells. In situ hybridization showed that DPP6-E is prominently expressed in hippocampal pyramidal cells, CGNs and in neurons in the superior colliculus. DPP6-E likely explains the quantitative discrepancies between reconstituted and the native currents of some neurons and provides additional evidence that alternative splicing of DPPLs contributes to the diversity of A-type K+ currents in neurons.

DPP6-E-specific riboprobes were prepared from the sequence of the exon encoding the DPP6-E N-terminus. PCR primers 5′-GGTACCTCCGCTCCCTCCACTT-3′ and 5′-CTCGAGCTTATGGCCTTTCCCTGGAG-3′ were used to amplify a 760 bp fragment from AK136075 (RIKEN/FANTOM). PCR amplification products were cloned into Topo TA sequencing vector (Invitrogen) and used to generate riboprobes as previously described [40]. Antisense digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were transcribed and hybridized at 65 °C with 40 μm slices cut from p30 ICR mice as described in [40].

HEK 293 cells plated at 50% confluence were cotransfected with green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-c3, Clontech) and the indicated channel components utilizing the FuGENE HD method (Roche Diagnostics) as described by the manufacturer and incubated for 24 h prior to recording. Whole cell currents were obtained at room temperature with 2–5 MOhm pipettes using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA) and protocols and solutions described in [40]. Junction potential was estimated at −10 mV and all reported potentials are corrected by this amount.

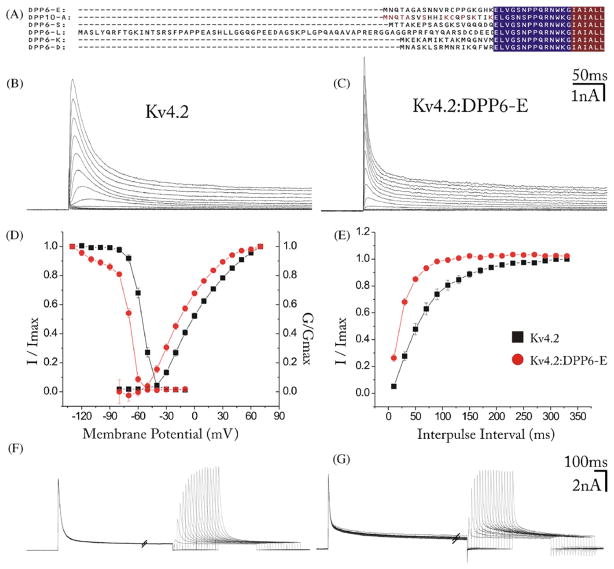

DPP6 and DPP10 are type II membrane glycoproteins with a single membrane-spanning sequence, a short intracellular amino-terminal domain and a very large extracellular sequence that contains two highly conserved domains: a β-propeller and a non-catalytic αβ-hydrolase fold [16,30,35]. The intracellular amino terminus is alternatively spliced resulting in protein isoforms that differ only in their intracellular N-terminal sequence [25,37]. A search of the GenBank EST database using the last 784 residues of the rat coding sequence of DPP6-S (M76427) revealed the presence of five alternatively spliced N-terminal exons resulting in five spliced DPP6 isoforms termed DPP6-S, DPP6-L, DPP6-E, DPP6-D, and DPP6-K, each with a divergent N-termini of 17 (DPP6-K, DPP6-D), 19 (DPP6-S), 20 (DPP6-E), and 75 (DPP6-L) amino acids preceding a common juxtamembrane region of 14 amino acids (Fig. 1A). Transcripts encoding DPP6-S, DPP6-L and DPP6-K were shown to have specific, but partially overlapping, expression patterns in brain, although all were shown to produce similar (although not identical) effects on Kv4 currents in heterologous cells [25]. DPP6-E and DPP6-D have not been studied.

Fig. 1.

DPP6-E modulates the kinetics and voltage-dependence of Kv4 Channels expressed in HEK 293 cells. (A) Comparison of the divergent N-termini of DPP6 spliced isoforms. Common juxtamembrane and transmembrane domains encoded by a common second exon are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. Only the first 6 amino acids of the transmembrane domain are shown. Letters in red indicate conserved amino acids in the N-termini, which are encoded in alternatively spliced exons. Also included for comparison is the N-terminus of DPP10-A. Shown is the alignment of the following rodent sequences: NP 034205 (DPP6-E); NP 001012205 (DPP10-A) M76427 (DPP6-S); M76426 (DPP6-L); CF743412 (DPP6-K); and CB585942 (DPP6-D). (B) Kv4.2-mediated A-type K+ currents in representative HEK 293 cells transfected with Kv4.2 DNA alone or (C) Kv4.2 plus DPP6-E cDNA at a ~1:1 molar ratio obtained by whole cell recording. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −90 mV followed by depolarizing test pulses from −90 to 40 mV in 10 mV increments. (D) Normalized conductance–voltage relation (G/Gmax) and steady-state inactivation curves (I/Imax) for the ISA in cells expressing Kv4.2 alone (black symbols) and Kv4.2 + DPP6-E (red symbols). Shown are averages from 6 cells. (E) Time course of the recovery from inactivation of the ISA in cells transfected with Kv4.2 (black squares) and Kv4.2 plus DPP6-E (red circles) at a ~1:1 molar ratio. The currents were recorded during test pulses to +40 mV following a pulse to the same voltage separated by increasing time intervals at −110 mV.(F) Representative currents from HEK 293 cells transected with Kv4.2 or (G) Kv4.2 plus DPP6-E at a ~1:1 molar ratio recorded under conditions described in (E). Error bars represent S.E.M. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure caption, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

DPP6-E is particularly interesting because it shows significant sequence similarity with the DPP10-A alternative spliced N-terminus (Fig. 1A), which has been shown to produce Kv4 currents with faster kinetics than DPP6-S, L, or K [11,40]. We therefore generated a cDNA containing the full coding sequence of DPP6-E and investigated the effects of this isoform on the currents expressed by Kv4.2 pore-forming subunits in the presence and absence of KChIP1 in HEK 293 cells.

DPP6-E had similar effects on Kv4 currents as those reported for other DPP6 isoforms (Fig. 1). DPP6-E accelerated current activation and inactivation, produced large negative shifts in the voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation and accelerated the rate of recovery from inactivation (Fig. 1B–G). The voltage-dependent properties and time constants of recovery from inactivation of the currents expressed by Kv4.2 channels were similar in the presence of DPP6-E and DPP6-S, the most abundant and best studied DPP6 isoform (G/Gmax: V0.5: −4 ± 0.8, −21.1 ± 2.2 and −26 ± 2.4 mV; k: 22.1 ± 0.8, 23.3 ± 1.3 and 25.8 ± 1.2 for Kv4.2, Kv4.2 with DPP6-E and Kv4.2 with DPP6-S, respectively. Inactivation: V0.5: −57 ± 0.5, −71.2 ± 0.5 and −70 ± 0.4; k: 4.7 ± 0.2, 5.1 ± 0.3 and 4.1 ± 0.3 for Kv4.2, Kv4.2 with DPP6-E and Kv4.2 with DPP6-S, respectively. τ of recovery at −110 mV: 72 ± 1.7, 31.5 ± 0.7 and 40.4 ± 2.2 ms, for Kv4.2, Kv4.2 with DPP6-E and Kv4.2 with DPP6-S, respectively).

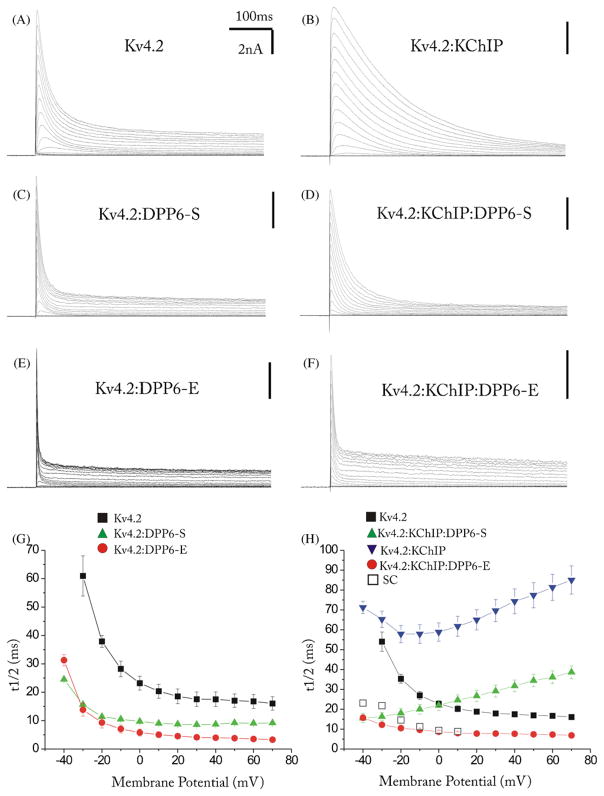

Although the voltage-dependence and rates of recovery from inactivation were similar with DPP6-S or DPP6-E, the kinetics of the currents was much faster when DPP6-E was present (Fig. 2). This was observed independently of whether Kv4.2 was expressed in the presence or absence of KChIP1.

Fig. 2.

ISAs inactivate faster in the presence of DPP6-E than in the presence of DPP6-S. (A)–(F) Kv4.2-mediated A-type K+ currents in representative HEK 293 cells transfected with the indicated cDNAs at equimolar ratios. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −90 mV followed by depolarizing test pulses from −90 to 70 mV in 10 mV increments. (G)–(H) Plots of the time at which half of the peak current is inactivated (t1/2) against membrane potential from the currents recorded in HEK 293 cells expressing Kv4.2 with or without KChIP in the absence or presence of DPP6-E or DPP6-S as indicated. In (H) open squares show the t1/2 of inactivation of FS and late-spiking cells in the superior colliculus reported by Saito and Isa [31]. Note the similarity between these native currents and those produced by the Kv4.2, KChIP, DPP6-E complex. Error bars represent S.E.M.

Not only were the kinetics faster in the presence of DPP6-E, but also the shape of the curve describing the voltage-dependence of the rate of inactivation of the ternary complex was different for the two DPP6 isoforms (Fig. 2H). The kinetics of inactivation of ternary (Kv4–KChIP–DPPL) Kv4 channels expressed in heterologous expression systems has an unusual voltage-dependence [2,11,38]. With increasing step depolarizations, the rate of inactivation slows down. This unusual behavior is caused by KChIPs and is also observed in cell expressing Kv4 and KChIP proteins but not in cells expressing only Kv4 proteins or Kv4 and DPPLs without KChIP [2,11]. KChIPs bind and immobilize the N-terminus of Kv4 proteins [27,39] and in doing so prevent a fast open-state inactivation that resembles the N-type inactivation of other transient K+ channels [8]. As a result, the channels inactivate predominantly from closed states [2,3,11,12]. Closed-state inactivation slows down during depolarization due to increased occupancy of open states and hence reduced residency in the inactivation-prone pre-open closed state.

Amarillo et al., [2] showed that the precise profile of the voltage-dependence of the inactivation rates observed in ternary channels depends in a complex fashion on the closed-state inactivation promoted by KChIPs and the acceleration of the inactivation rate and voltage-dependence shifts produced by DPPLs [2]. The native ISA in hippocampal pyramidal cells and CGNs also shows this unusual property, resembling ternary complexes containing DPP6-S [2,9,17,19,24]. However, ternary complexes containing DPP6-E instead of DPP6-S do not show this behavior (Fig. 2H). In ternary channels containing DPP6-E, the rate of inactivation speeds up with increasing depolarization. This effect of DPP6-E is similar to that observed in ternary complexes containing DPP10-A [11].

Nadal et al., [25] used in situ hybridization to compare the distribution of mRNA transcripts of three DPP6 isoforms, DPP6-S, -L and -K in adult brain. These studies showed that each isoform had a specific, but sometimes overlapping expression pattern. DPP6-S and DPP6-K showed widespread expression in brain. In contrast, DPP6-L was only expressed in a few neuronal populations.

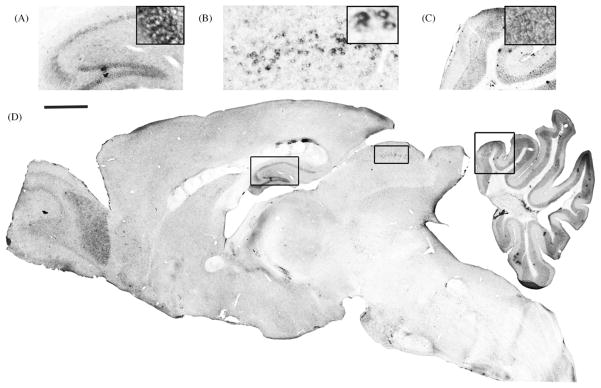

Here we used non-radioactive in situ hybridization (NR-ISH) with probes specific to the exon encoding the DPP6-E spliced version to determine the distribution of DPP6-E transcripts in mouse brain. Like DPP6-L, DPP6-E showed a very restricted expression pattern. Prominent signals were detected in granule cells of the cerebellar cortex, in the principal neurons of the hippocampal formation, including pyramidal neurons in the CA1–CA3 fields and granule cells of the dentate gyrus, granule cells in the olfactory bulb, and in neurons in intermediary layers of the superior colliculus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of DPP6-E mRNA transcripts in mouse brain. DPP6-E exon-specific cRNA probes were used to localize DPP6-E expression in mouse brain using non-radioactive in situ hybridization. Enlarged sections of specific staining including the hippocampus (A); intermediary layer of the superior colliculus (B); and cerebellum (C) are taken from the areas indicated by boxes in the full sagital section (D). Further enlargement of the staining pattern from these fields is shown in inset images. Calibration bar shows 1 mm for image in (D).

The expression of DPP6-E in the superior colliculus is particularly interesting because the ISA in these neurons inactivates faster than the ISA in CGNs or in hippocampal pyramidal cells [31], matching the inactivation rates observed in heterologous cells expressing KChIP1 and DPP6-E (Fig. 2H). Moreover, as in heterologous cells expressing KChIP1 and DPP6-E (Fig. 2H) the voltage-dependence of inactivation rate of the ISA in neurons in the superior colliculus does not slow down with depolarization [31]. The remarkable qualitative and quantitative similarity of the rates of inactivation of the native and the reconstituted current is strong evidence that native channels include DPPL proteins.

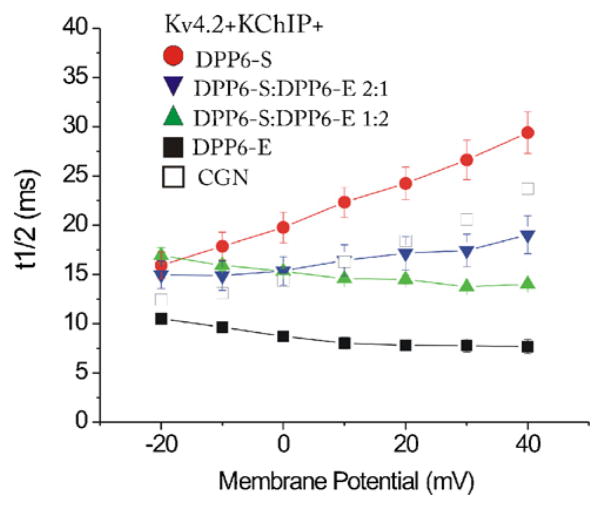

Of the two DPPL genes only DPP6 is expressed in the granule cell layer of the cerebellar cortex and in pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus [40]. In these structures DPP10 is expressed in Purkinje cells and GABAergic interneurons, respectively. However, CGNs and hippocampal pyramidal cells prominently express multiple DPP6 isoforms [25], including DPP6-S. As shown here, DPP6-E is also prominently expressed in the CGNs and in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Fig. 3). We therefore asked whether mixtures of DPP6-E and DPP6-S in the presence of KChIP1 result in currents with faster kinetics that preserve the slow down of inactivation rate with depolarization that is observed with channels containing DPP6-S and in the native currents in CGNs and hippocampal pyramidal neurons. As shown in Fig. 4, in cells expressing Kv4.2, KChIP1 and DPP6-S, increasing concentrations of DPP6-E produced faster inactivation. When the proportion of transfected DPP6-S and DPP6-E cDNAs was higher than ~1 the inactivation rate slowed down with depolarization, but the decrease in inactivation rate with depolarization was lost when the proportion was ~1:1 or less.

Fig. 4.

Intermediary inactivation kinetics produced by Kv4–KChIP channels expressed with different ratios of DPP6-E and DPP6-S. Plotted are the t1/2 of inactivation against membrane potential for HEK 293 cells transfected with Kv4.2 and KChIP with either DPP6-S, DPP6-E or the indicated mixtures of both isoforms. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −90 mV followed by depolarizing test pulses from −20 to 40 mV in 10 mV increments. The open squares represent the t1/2 of inactivation of A-type currents recorded from cerebellar granule neurons (CGN) reported by Amarillo et al. (2008). Note that the ratio of DPP6-S to DPP6-E determines the effect of depolarization on the t1/2 of inactivation for the currents in the heterologous system and that the native currents fall within the range of kinetics produced by these mixtures. Error bars represent S.E.M.

We have shown that the currents produced by Kv4 channels containing one of the spliced products of the DPP6 gene known as DPP6-E, inactivate much faster than the currents mediated by channels containing DPP6-S, the most abundant and most widely expressed DPP6 spliced isoform [25]. DPP6-E and DPP6-S differ only in the intracellular N-terminal sequence (19 residues in DPP6-S and 20 in DPP6-E); they have an identical juxtamembrane and membrane-spanning sequence and identical extracellular domains (Fig. 1A, [25]). One splice product of the DPP10 gene, DPP10A [11,13,40] also produces channels with fast inactivation rates.

In addition to producing faster kinetics, these splice variants occlude the increase in inactivation time constants with voltage induced by KChIP. There are significant similarities between the DPP6-E and DPP10-A spliced sequences, supporting the view that these sequences are responsible for a faster inactivation rate that cannot be prevented by KChIPs, presumably because KChIPs are unable to bind and sequester the DPP6-E and DPP10-A N-terminus.

We also showed that when heterologous cells expressed combinations of DPP6-S and DPP6-E, the currents inactivated at intermediary rates and showed intermediary behavior in terms of the voltage-dependence of the inactivation rate.

Our data suggests that the inactivation properties of the ISA in native neurons depend on the DPPL isoforms present. In neurons expressing only DPP6-E, as in neurons in the superior colliculus, the ISA inactivates very fast and does not slow down with depolarization. On the other hand, in neurons expressing DPP6-E and other DPPLs the inactivation rate is slower than in the superior colliculus and, depending on the relative concentrations of each isoform, may slow down with depolarization, as is the case in CGNs and hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Yet the rate of inactivation in these cells is faster than it would be if DPP6-E was not present.

Kv4 channel complexes are likely to include four DPPL molecules (two dimers) [34] and many neuronal populations express multiple DPPL isoforms [11,25]. Given that DPPLs can form heterodimers [35], the number of possible combinations of DPPLs in neurons, and hence the diversity in ISA properties that could be realized by alternative splicing of DPPLs could be large.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcela Nadal for helpful discussions and assistance in obtaining the DPP6-E N-terminus. Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS045217 to B.R.

References

- 1.Adams JP, Anderson AE, Varga AW, Dineley KT, Cook RG, Pfaffinger PJ, Sweatt JD. The A-type potassium channel Kv4.2 is a substrate for the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2277–2287. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarillo Y, De Santiago-Castillo JA, Dougherty K, Maffie J, Kwon E, Covarrubias M, Rudy B. Ternary Kv4.2 channels recapitulate voltage-dependent inactivation kinetics of A-type K+ channels in cerebellar granule neurons. J Physiol. 2008;586:2093–2106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck EJ, Bowlby M, An WF, Rhodes KJ, Covarrubias M. Remodelling inactivation gating of Kv4 channels by KChIP1, a small-molecular-weight calcium-binding protein. J Physiol. 2002;538:691–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekkers JM. Distribution and activation of voltage-gated potassium channels in cell-attached and outside-out patches from large layer 5 cortical pyramidal neurons of the rat. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 3):611–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai X, Liang CW, Muralidharan S, Kao JP, Tang CM, Thompson SM. Unique roles of SK and Kv4.2 potassium channels in dendritic integration. Neuron. 2004;44:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Yuan LL, Zhao C, Birnbaum SG, Frick A, Jung WE, Schwarz TL, Sweatt JD, Johnston D. Deletion of Kv4.2 gene eliminates dendritic A-type K+ current and enhances induction of long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12143–12151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2667-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor JA, Stevens CF. Voltage clamp studies of a transient outward membrane current in gastropod neural somata. J Physiol. 1971;213:21–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebauer M, Isbrandt D, Sauter K, Callsen B, Nolting A, Pongs O, Bahring R. N-type inactivation features of Kv4.2 channel gating. Biophys J. 2004;86:210–223. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu HJ, Carrasquillo Y, Karim F, Jung WE, Nerbonne JM, Schwarz TL, Gereau RWT. The kv4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerng HH, Lauver AD, Pfaffinger PJ. DPP10 splice variants are localized in distinct neuronal populations and act to differentially regulate the inactivation properties of Kv4-based ion channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:604–624. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerng HH, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Molecular physiology and modulation of somatodendritic A-type potassium channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:343–369. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jerng HH, Qian Y, Pfaffinger PJ. Modulation of Kv4.2 channel expression and gating by dipeptidyl peptidase 10 (DPP10) Biophys J. 2004;87:2380–2396. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston D, Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Poolos NP, Watanabe S, Colbert CM, Migliore M. Dendritic potassium channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 1):75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Nadal MS, Clemens AM, Baron M, Jung SC, Misumi Y, Rudy B, Hoffman DA. Kv4 accessory protein DPPX (DPP6) is a critical regulator of membrane excitability in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1835–1847. doi: 10.1152/jn.90261.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kin Y, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y. Biosynthesis and characterization of the brain-specific membrane protein DPPX, a dipeptidyl peptidase IV-related protein. J Biochem. 2001;129:289–295. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klee R, Ficker E, Heinemann U. Comparison of voltage-dependent potassium currents in rat pyramidal neurons acutely isolated from hippocampal regions CA1 and CA3. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1982–1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korngreen A, Sakmann B. Voltage-gated K+ channels in layer 5 neocortical pyramidal neurones from young rats: subtypes and gradients. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 3):621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lien CC, Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Jonas P. Gating, modulation and subunit composition of voltage-gated K(+) channels in dendritic inhibitory interneurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2002;538:405–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liss B, Franz O, Sewing S, Bruns R, Neuhoff H, Roeper J. Tuning pacemaker frequency of individual dopaminergic neurons by Kv4.3L and KChIp3.1 transcription. EMBO J. 2001;20:5715–5724. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Losonczy A, Makara JK, Magee JC. Compartmentalized dendritic plasticity and input feature storage in neurons. Nature. 2008;452:436–441. doi: 10.1038/nature06725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maffie J, Rudy B. Weighing the evidence for a ternary protein complex mediating A-type K+ channels in neurons. J Physiol. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161620. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malin SA, Nerbonne JM. Elimination of the fast transient in superior cervical ganglion neurons with expression of KV4.2W362F: molecular dissection of IA. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5191–5199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Monyer H, Jonas P. Functional and molecular differences between voltage-gated K+ channels of fast-spiking interneurons and pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8111–8125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08111.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadal MS, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Differential characterization of three alternative spliced isoforms of DPPX. Brain Res. 2006;1094:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Ma Y, Mo W, Goldberg EM, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Neubert TA, Rudy B. The CD26-related dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein DPPX is a critical component of neuronal A-type K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor DL., Jr Three-dimensional structure of the KChIP1–Kv4.3 T1 complex reveals a cross-shaped octamer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakers GM, Storm JF. A postsynaptic transient K(+) current modulated by arachidonic acid regulates synaptic integration and threshold for LTP induction in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10144–10149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152620399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren X, Hayashi Y, Yoshimura N, Takimoto K. Transmembrane interaction mediates complex formation between peptidase homologues and Kv4 channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudy B, Maffie J, Amarillo Y, Clark B, Goldberg E, Jeong H, Kruglikov I, Kwon E, Nadal M, Zagha E. Structure and function of voltage-gated K+ channels: Kv1 to Kv9 subfamilies. In: Squire L, Albright T, Bloom F, Gage F, Spitzer N, editors. New Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands: in press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito Y, Isa T. Voltage-gated transient outward currents in neurons with different firing patterns in rat superior colliculus. J Physiol. 2000;528(Pt 1):91–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serodio P, Kentros C, Rudy B. Identification of molecular components of Atype channels activating at subthreshold potentials. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1516–1529. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh B, Ogiwara I, Kaneda M, Tokonami N, Mazaki E, Baba K, Matsuda K, Inoue Y, Yamakawa K. A Kv4.2 truncation mutation in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soh H, Goldstein SA. I SA channel complexes include four subunits each of DPP6 and Kv4.2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15072–15077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706964200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strop P, Bankovich AJ, Hansen KC, Garcia KC, Brunger AT. Structure of a human A-type potassium channel interacting protein DPPX, a member of the dipeptidyl aminopeptidase family. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1055–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson SM. IA in play. Neuron. 2007;54:850–852. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada K, Yokotani N, Hunter C, Doi K, Wenthold RJ, Shimasaki S. Differential expression of two distinct forms of mRNA encoding members of a dipeptidyl aminopeptidase family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:197–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Shahidullah M, Rocha CA, Strang C, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Functionally active t1-t1 interfaces revealed by the accessibility of intracellular thiolate groups in kv4 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:55–69. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Yan Y, Liu Q, Huang Y, Shen Y, Chen L, Chen Y, Yang Q, Hao Q, Wang K, Chai J. Structural basis for modulation of Kv4 K+ channels by auxiliary KChIP subunits. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:32–39. doi: 10.1038/nn1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zagha E, Ozaita A, Chang SY, Nadal MS, Lin U, Saganich MJ, McCormack T, Akinsanya KO, Qi SY, Rudy B. DPP10 modulates Kv4-mediated A-type potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18853–18861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]