Abstract

Background

Anthropometry is a necessary aspect of aging-related research, especially in biomechanics and injury prevention. Little information is available on inertial parameters in the geriatric population that account for gender and obesity effects. The goal of this study was to report body segment parameters in adults aged 65 years and older, and to investigate the impact of aging, gender and obesity.

Methods

Eighty-three healthy old (65–75 yrs) and elderly (>75 yrs) adults were recruited to represent a range of body types. Participants underwent a whole body dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scan. Analysis was limited to segment mass, length, longitudinal center of mass position, and frontal plane radius of gyration. A mixed-linear regression model was performed using gender, obesity, age group and two-way and three-way interactions (α=0.05).

Findings

Mass distribution varied with obesity and gender. Males had greater trunk and upper extremity mass while females had a higher lower extremity mass. In general, obese elderly adults had significantly greater trunk segment mass with less thigh and shank segment mass than all others. Gender and obesity effects were found in center of mass and radius of gyration. Non-obese individuals possessed a more distal thigh and shank center of mass than obese. Interestingly, females had more distal trunk center of mass than males.

Interpretation

Age, obesity and gender have a significant impact on segment mass, center of mass and radius of gyration in old and elderly adults. This study underlines the need to consider age, obesity and gender when utilizing anthropometric data sets.

Keywords: anthropometry, aging, obesity

1. Introduction

Recent years have shown a growing population of adults aged 65 years and older in the United States. Injuries, especially resulting from falls, are a serious health burden for older adults. In 2003, injury ranked 6th in leading causes of death among old adults aged 65–74 years and 7th among elderly adults aged 75–84 years, making it comparable to diabetes and Alzheimer's disease (Dellinger and Stevens, 2006; Gillespie et al., 2003). While injuries are associated with substantial economic costs, the costs of non-fatal injuries doubled from ages 65–74 to 75–84 suggesting an increased burden with increasing age (Dellinger and Stevens, 2006; Stevens, 2005). These statistics point to a need for a concerted research effort to reduce injury rates in older adults and the economic costs associated with them (Dellinger and Stevens, 2006; Nikolova and Toshev, 2007; Stevens, 2005).

Anthropometry is necessary to develop biomechanical models of the body used in many types of injury prevention research (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Hughes et al., 2004; Kuczmarski et al., 2000; Matrangola et al., 2008). Typically, body segment parameters are derived from regression equations or models based on cadaveric studies (Chandler et al., 1975; Dempster, 1955) or imaging (de Leva, 1996). However, the use of these parameter estimates has been shown inaccurate in various populations including children (Bauer et al., 2007; Ganley and Powers, 2004) and middle-aged adults (Durkin and Dowling, 2003). Body segment parameter inaccuracies may be due to variations in tissue density within and between body segments as well as age and gender related redistribution of mass (Jensen and Fletcher, 1994; Stoudt, 1981). The effect of obesity may be another reason for the inaccuracies associated with traditional body segment parameter estimations (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Matrangola et al., 2008).

Obesity and overweight is a major and growing health concern in the United States with older adults over the age of 65 having the highest rate of obesity increase (Flegal et al., 2002; Ogden et al., 2006). Overweight adults aged 65 and older have a greater risk of impaired physical function and are at higher risk for injury (Lang et al., 2008; Ostbye et al., 2007). The biomechanical investigations in balance and mobility in obese adults have shown that obesity is associated with difficulties in postural control and gait variations, both of which may increase injury risk (Colné et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2008). Additional research is necessary to determine the impact of obesity on injury risk (Wearing et al., 2006). Such research requires body segment parameters that accurately represent obese older adults.

There is little information available on inertial parameters in an obese geriatric population (Barbosa et al., 2005; Hughes et al., 2004; Muri et al., 2008; Pearsall et al., 1996). Muri et al. (2008), modeling the body as geometric solids, found significant differences for all the inertial properties of the upper arm, forearm center of mass and thigh mass in old adults compared to young adults. However, utilizing geometric models to derive segment inertial parameters may not accurately represent all the changes that occur with age (Muri et al., 2008). Additionally, obesity was not investigated in this study. Certain medical imaging techniques can take into account age, gender and obesity related differences in body segment parameters. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) has been validated as a reliable in-vivo method to derive body segment parameters that includes tissue density, age, gender and obesity (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Ganley and Powers, 2004; LaForgia et al., 2009). Durkin and Dowling (2003) used imaging to note differences in body segment parameters of the upper and lower extremities between middle-aged and young adults. Matrangola et al. (2008) utilized imaging to find significant differences in inertial parameters with weight loss in middle-aged males. However, no imaging study has investigated gender-specific inertial body segment parameters in an obese geriatric population.

In order to develop biomechanical models of injury prevention research, age-related changes in body segment parameters that incorporate gender and obesity must be understood. The aim of this study was to report body segment parameters of adults aged 65 years and older, and quantify the effects of obesity and gender on these parameters.

2. Methods

Eighty-three healthy adults, screened for metal implants, were divided into 8 subgroups based on gender (female; male), obesity determined based on body mass index (BMI) (BMI≤30, non-obese; BMI>30, obese) and age (65–75 yrs, old; >75 yrs, elderly) (Table 1). Written informed consent approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to participation.

Table 1.

Subject sample characteristics

| Mean (Standard Deviation) [Range] |

Female | Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Elderly | Old | Elderly | |||||

| Non-obese (n=8) |

Obese (n=10) |

Non-obese (n=13) |

Obese (n=11) |

Non-obese (n=7) |

Obese (n=10) |

Non-obese (n=14) |

Obese (n=10) |

|

| Height (m) | 1.63 (0.03) [1.58–1.69] |

1.59 (0.06) [1.47–1.71] |

1.57 (0.07) [1.46–1.66] |

1.56 (0.08) [1.46–1.67] |

1.72 (0.08) [1.62–1.82] |

1.74 (0.06) [1.64–1.85] |

1.74 (0.05) [1.64–1.81] |

1.73 (0.06) [1.62–1.82] |

| Mass (kg) | 65.80 (7.94) [54.40–76.50] |

87.78 (14.78) [70.40–124.20] |

61.17 (6.52) [52.20–72.80] |

83.60 (10.92) [65.30–105.60] |

80.29 (12.60) [67.00–97.00] |

102.00 (11.50) [88.70–122.50] |

78.39 (10.00) [56.00–97.10] |

102.10 (18.14) [83.30–133.81] |

| BMI | 24.82 (3.68) [19.86–28.97] |

34.72 (4.57) [31.18–47.03] |

25.00 (2.79) [20.41–29.76] |

34.11 (3.09) [30.18–39.41] |

26.99 (1.98) [25.28–29.61] |

33.75 (2.09) [30.85–38.15] |

25.94 (2.90) [19.75–29.71] |

33.97 (4.20) [30.14–41.26] |

| Age (yrs) | 70.36 (2.42) [66.95–73.48] |

70.88 (2.35) [66.69–73.66] |

79.23 (2.94) [75.10–85.66] |

79.47 (2.76) [75.65–83.68] |

69.84 (3.28) [65.68–74.97] |

70.59 (2.64) [66.46–74.99] |

79.08 (3.15) [75.58–85.02] |

78.49 (2.02) [76.41–82.24] |

Each participant underwent a whole body DXA scan (Hologic QDR 1000/W, Bedford, MA, USA) lying supine. For each DXA scan, segment boundaries were identified similar to de Leva (1996) using bony landmarks or anatomical defined planes. The head segment was defined from vertex to the midpoint of the gonions. The neck segment was defined from the midpoint of the gonions to midpoint of the right and left acromion. The forearm was defined from elbow joint center to wrist joint center. The upper arm was defined from midpoint of the right and left acromion following the trunk/upper arm plane to elbow joint center. The trunk/upper arm plane ran through the acromion to the axilla and was used to divide the trunk and upper arm segments. The trunk was defined from midpoint of the right and left acromion following the trunk/upper arm plane to midpoint of the hip joint center following the trunk/thigh plane. The trunk/thigh plane located just lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine and the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis was used to divide the trunk and thigh segments. The thigh was defined from hip joint center following the trunk/thigh plane to knee joint center with the mass of pelvis not included. The shank was defined from knee joint center to lateral malleolus. The dominant appendage only was used for this analysis.

Each scan was divided into 3.9 cm sections that were perpendicular to the long axis of the bone and processed in a method similar to that described in Ganley and Powers (2004). Each scan was characterized by a pixel size of .205 cm by 1.30 cm, i.e. an area of 0.27 cm2 (same resolution as in Ganley and Powers, 2004). Assumed densities for bone (2.5–3.0 g/cc), fat (0.9 g/cc), and lean (1.08 g/cc) tissue were used (Hologic QDR 1000/W, Bedford, MA, USA).

Segment mass (SM) as a percent of body mass (%BM), segment length (SL) as a percent of total height (%H), distance from the center of mass to the proximal end of the segment (COM) as a percent of segment length (%SL), and radius of gyration (k) about an axis perpendicular to the frontal plane, through the center of mass, as a percent of segment length (%SL) were determined (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Ganley and Powers, 2004). These dependent variables were each entered individually in a mixed-linear regression model. The independent fixed factors were gender, obesity and age group. Analyses included main effects, two-way and three-way interactions. Post hoc analyses included comparisons using a Tukey test. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results

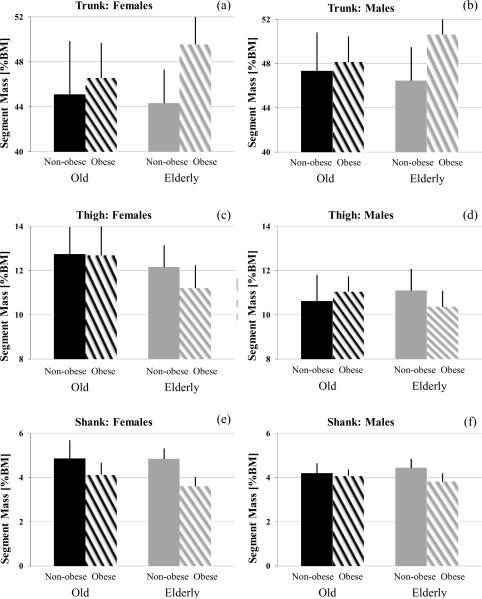

Minimal significant effects were noted in SL. Females had a 1.13%H longer head but 0.54%H shorter neck segment than males. Elderly possessed a 0.40%H longer upper arm than old adults. Obesity-age interactions revealed obese elderly individuals as having longer a trunk segment than all other groups (Table 2). Trunk SM accounted for a significantly greater percent of body mass, 2.92%BM, in obese individuals compared to non-obese individuals. Non-obese individuals had significantly greater SM of their head (1.30%BM), forearm (0.17%BM) and shank (0.67%BM) compared to obese individuals. Males had greater neck (0.27%BM), upper arm (0.13%BM), forearm (0.22%BM) and trunk (1.76%BM) SM while females had a higher thigh (1.42%BM) and shank (0.23%BM) SM (Table 3). Two-way interaction effects with obesity and age group were found in trunk, thigh and shank SM. In general, obese elderly adults had significantly higher trunk (3.79%BM) SM with less thigh (0.93%BM) and shank (0.71%BM) SM than non-obese elderly and all old adults. Obesity-gender interaction effects were noted in the shank SM with non-obese females having the greatest SM by 0.80%BM (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Segment length as a percent of total height. Mean (SD) [Range] presented for each subgroup. Only significant main effects are noted for brevity.

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Elderly | Old | Elderly | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese |

| Headg | 14.04 (0.87) | 13.61 (1.14) | 13.42 (0.87) | 13.02 (0.83) | 12.33 (1.33) | 12.58 (0.43) | 12.56 (0.75) | 12.11 (0.71) |

| Neckg | 2.60 (0.97) | 2.85 (1.19) | 2.42 (1.34) | 2.40 (1.01) | 3.34 (1.65) | 3.07 (1.03) | 3.16 (1.04) | 2.87 (1.03) |

| Trunk | 34.18 (1.45) | 34.40 (0.90) | 34.70 (1.39) | 35.83 (1.25) | 34.68 (1.12) | 34.15 (1.23) | 33.83 (1.28) | 34.81 (1.12) |

| Upper arma | 19.82 (1.08) | 20.32 (0.54) | 20.76 (0.86) | 20.42 (0.75) | 20.62 (0.45) | 20.14 (0.79) | 20.78 (0.55) | 20.53 (0.54) |

| Forearm | 15.74 (0.71) | 15.97 (.076) | 16.31 (1.07) | 16.25 (0.66) | 16.10 (0.48) | 16.49 (0.84) | 16.30 (0.43) | 16.33 (0.87) |

| Thigh | 27.18 (1.09) | 27.28 (.059) | 27.19 (0.98) | 26.68 (1.14) | 26.89 (1.23) | 26.88 (0.49) | 27.10 (0.86) | 27.21 (0.82) |

| Shank | 24.00 (0.89) | 24.08 (0.55) | 24.45 (0.92) | 23.65 (0.88) | 24.19 (0.38) | 24.04 (0.81) | 24.15 (0.66) | 23.99 (0.91) |

obesity effect

gender effect

age effect

Table 3.

Segment mass as a percent of total body mass. Mean (SD) [Range] presented for each subgroup. Only significant main effects are noted for brevity.

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old |

Elderly |

Old |

Elderly |

|||||

| Mean (SD) | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese |

| Heado | 6.89 (1.04) | 5.30 (0.77) | 6.67 (0.74) | 5.27 (0.60) | 6.39 (1.04) | 5.23 (0.40) | 6.25 (0.67) | 5.19 (0.64) |

| Neckg | 1.40 (0.46) | 1.43 (0.48) | 1.12 (0.70) | 1.27 (0.53) | 1.58 (0.80) | 1.66 (0.59) | 1.55 (0.62) | 1.56 (0.49) |

| Trunko g | 45.11 (4.75) | 46.56 (3.12) | 44.33 (3.00) | 49.58 (2.59) | 47.34 (3.50) | 48.15 (2.32) | 46.47 (3.01) | 50.65 (1.48) |

| Upper armg | 2.32 (0.34) | 2.48 (0.30) | 2.41 (0.19) | 2.50 (0.24) | 2.57 (0.14) | 2.56 (0.23) | 2.52 (0.18) | 2.59 (0.22) |

| Forearmo g | 1.46 (0.20) | 1.28 (0.08) | 1.47 (0.20) | 1.26 (0.18) | 1.70 (0.16) | 1.56 (0.17) | 1.60 (0.16) | 1.47 (0.17) |

| Thighg a | 12.74 (1.24) | 12.68 (1.56) | 12.16 (1.00) | 11.22 (1.03) | 10.62 (1.19) | 11.06 (0.69) | 11.09 (0.98) | 10.36 (0.72) |

| Shanko g | 4.86 (0.83) | 4.14 (0.53) | 4.84 (0.48) | 3.61 (0.42) | 4.20 (0.45) | 4.09 (0.27) | 4.44 (0.42) | 3.82 (0.38) |

obesity effect

gender effect

age effect

Figure 1.

Mean segment mass of the trunk (a,b), thigh (c,d) and shank (e,f) in females and males, left and right respectively. Non-obese shown as solid bars and obese as hashed bars with old adults in black and elderly in gray. Obesity group was significant in trunk and shank SM. Gender was significant in trunk, thigh and shank SM. Obesity age interaction effects were found in trunk, thigh and shank SM. Obese elderly adults had significantly higher trunk SM with less thigh and shank SM than non-obese elderly and all older adults. Obesity gender interaction effects were noted in the shank SM with non-obese females having the greatest SM. Standard errors are provided.

Significant gender and obesity effects were also found in COM and k. Non-obese individuals possessed a 1.35%SL and 0.47%SL more distal COM in the thigh and shank, respectively, than obese individuals. Males had more distal head (1.56%SL), neck (2.81%SL), and shank (0.97%SL) COM but more proximal trunk (1.56%SL) and upper arm (1.29%SL) COM compared to females. Obesity-gender interaction effects were found in head COM with non-obese females having a 2.31%SL more superior COM than all other groups (Table 4). Finally, obese individuals had a 0.49%SL greater head k with 0.64%SL and 0.38%SL less trunk and forearm k, respectively, than non-obese individuals. Males reported a greater neck (9.88%SL) and shank (0.36%SL) k than females. Two-way interaction effects with obesity and gender found that obese females had 0.47%SL less upper arm k than all other groups (Table 5).

Table 4.

Segment center of mass position with respect to the proximal border as a percent of segment length. Mean (SD) [Range] presented for each subgroup. Only significant main effects are noted for brevity.

| Female |

Male |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old |

Elderly |

Old |

Elderly |

|||||

| Mean (SD) | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese |

| Headg | 51.31 (2.33) | 53.24 (2.32) | 52.69 (2.16) | 54.57 (2.35) | 55.19 (2.45) | 53.90 (1.49) | 53.90 (1.52) | 55.05 (2.02) |

| Neckg | 54.39 (4.82) | 54.15 (5.45) | 51.56 (3.65) | 52.86 (3.72) | 56.90 (2.50) | 55.28 (4.75) | 56.46 (4.10) | 55.56 (3.99) |

| Trunkg | 55.00 (0.84) | 55.03 (0.65) | 55.60 (1.35) | 54.72 (0.91) | 52.84 (0.74) | 53.61 (0.89) | 53.72 (1.10) | 53.94 (0.98) |

| Upper armg | 51.46 (1.40) | 51.52 (1.79) | 51.25 (1.32) | 51.05 (1.64) | 49.64 (1.91) | 50.28 (1.67) | 50.17 (2.12) | 50.03 (0.86) |

| Forearm | 44.27 (1.92) | 44.53 (1.98) | 43.94 (1.19) | 45.04 (1.66) | 44.34 (1.55) | 44.67 (0.92) | 44.13 (1.38) | 44.60 (1.66) |

| Thigho | 46.34 (1.36) | 44.84 (2.35) | 46.48 (1.59) | 44.76 (1.27) | 46.10 (1.55) | 45.34 (0.92) | 46.50 (1.08) | 45.07 (0.96) |

| Shanko g | 40.34 (0.71) | 39.91 (1.69) | 40.21 (1.17) | 39.38 (0.92) | 41.26 (0.78) | 40.58 (0.56) | 40.92 (0.96) | 40.95 (0.79) |

obesity effect

gender effect

age effect

Table 5.

Frontal plane radius of gyration as a percent of segment length. Mean (SD) [Range] presented for each subgroup. Only significant main effects are noted for brevity.

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Elderly | Old | Elderly | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese | Non-obese | Obese |

| Heado | 24.43 (0.76) | 24.63 (0.64) | 24.08 (0.26) | 24.80 (0.67) | 24.45 (0.49) | 24.96 (0.59) | 24.44 (0.42) | 24.97 (0.52) |

| Neckg | 11.89 (12.72) | 9.74 (12.61) | 3.86 (9.02) | 9.58 (12.37) | 24.11 (0.80) | 14.30 (12.32) | 19.08 (10.36) | 17.10 (11.80) |

| Trunkg | 27.83 (0.67) | 26.91 (0.31) | 27.52 (0.47) | 26.83 (0.48) | 27.26 (0.38) | 26.89 (0.27) | 27.42 (0.40) | 26.84 (0.38) |

| Upper arm | 25.38 (0.51) | 24.62 (0.59) | 25.19 (0.67) | 24.85 (0.35) | 24.87 (0.79) | 25.32 (0.51) | 25.34 (0.48) | 25.16 (0.50) |

| Forearmo | 25.85 (0.58) | 25.51 (0.60) | 26.07 (0.70) | 25.27 (0.78) | 25.77 (0.49) | 25.53 (0.61) | 25.87 (0.72) | 25.72 (0.58) |

| Thigh | 25.77 (0.42) | 25.69 (0.55) | 25.86 (0.50) | 25.57 (0.38) | 25.42 (0.23) | 25.70 (0.23) | 25.82 (0.35) | 25.61 (0.41) |

| Shankg | 26.82 (0.63) | 26.85 (0.53) | 26.66 (0.50) | 26.45 (0.49) | 27.10 (0.45) | 26.91 (0.39) | 27.20 (0.41) | 27.00 (0.56) |

obesity effect

gender effect

age effect

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to report inertial body segment parameters in old and elderly adults (aged 65 years and older) and to investigate the impact of aging, gender and obesity on these anthropometric parameters. Mass distribution was found to vary with obesity and gender. Males had greater trunk and upper extremity segment mass while females had a higher lower extremity segment mass. In general, obese elderly adults had significantly greater trunk segment mass with less thigh and shank segment mass than all others. Gender and obesity effects were found in center of mass and radius of gyration. Non-obese individuals possessed a more distal thigh and shank center of mass than obese. Females had a more distal trunk center of mass than males. In summary, age, obesity and gender had a significant impact on segment mass, center of mass and radius of gyration in old and elderly adults.

Mass distribution was found to vary with obesity and gender. Trunk SM accounted for significantly greater, 2.92%BM, in obese individuals while head (1.30%BM), forearm (0.17%BM) and shank (0.67%BM) SM accounted for significantly less compared to non-obese individuals. Increases in trunk SM agree with previous literature stating that increased BMI is highly correlated to increases in waist circumference and abdominal fat (Hughes et al., 2004; Janssen and Mark, 2006; Okosun et al., 2004; Price et al., 2006). Males had a greater SM in upper extremity segments (0.14% in upper arm and 0.22% in forearm) and 1.75% greater trunk while females had a higher SM in lower extremity segments (1.42% in thigh and 0.22% in shank) in the current study. Males have been previously reported with higher trunk SM compared to females (Jensen and Fletcher, 1994; Okosun et al., 2004; Price et al., 2006). Similar to results found in the current study, middle-aged females have previously reported as having almost 1% greater thigh SM compared to males (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Hughes et al., 2004; Jensen and Fletcher, 1994). Additionally, previously reported gender and aging differences in segment volume and adipose distribution may help explain these findings with males having higher trunk values than females (Hughes et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007). These gender trends seem to carry into an older population. Interaction effects of the current study revealed that obese elderly adults had significantly higher trunk (3.79%BM) SM with less thigh (0.93%BM) and shank (0.71%BM) SM than non-obese elderly and all old adults. Increased waist girth and circumference, which could contribute to increased trunk SM, has been previously noted with increasing age and obesity (Hughes et al., 2004; Muri et al., 2008; Price et al., 2006).

Gender and obesity effects were also found in COM. Non-obese individuals possessed a more distal COM in the thigh (1.35%SL) and shank (0.47%SL) than obese. Although there is no literature on obesity effects on COM in this age group, Matrangola et al. (2008) noted a more distal thigh COM in middle-aged males (0.75%) after weight loss (Matrangola et al., 2008). Similarly, the current study found differences with non-obese individuals having a 1.35% more distal thigh COM. Males had more distal head (1.56%SL), neck (2.81%SL) and shank (0.97%SL) COM but more proximal trunk (1.56%SL) and upper arm (1.29%SL) COM compared to females in the current study. A more distal trunk COM in the female group may seem counterintuitive. However, Okada et al. (1996) reported gender differences in trunk mass distribution. Elderly females carried more mass in the lower trunk compared to the upper trunk and the opposite was true in males. (Okada et al., 1996). An increased mass in the lower trunk and less in the upper trunk would translate into a more distal trunk COM in elderly females.

A small number of main effects were noted for k. The current study found that obese individuals had a 0.49%SL greater head k with 0.64%SL and 0.38%SL less trunk and forearm k, respectively, than non-obese individuals. A decrease in k was noted in all segments with weight loss in middle-aged males (Matrangola et al., 2008). This would imply that a decrease in obesity, non-obese individuals, would be associated with a smaller k. This is not what was found in this study, as the obese individuals presented here had smaller k in most segments than the non-obese group. Matrangola et al. (2008) found a decrease of 1.87% in trunk k with weight loss. The current study found that non-obese individuals had a 1.35% greater trunk k than obese. Males reported a greater neck (9.88%SL) and shank (0.36%) k than females in the current study. Similar gender effects were noted in previous literature with old males as having a greater shank k than old females (Durkin and Dowling, 2003). Additionally, obese females had a 0.47%SL less upper arm k than all other groups. In general, there is little reported in the literature on the effect of obesity on body segment parameters, especially COM and k. However, previous research has acknowledged that wide ranges in COM and k, especially in the thigh, might be attributed to variations in body type or obesity (Durkin and Dowling, 2003).

While the body segment parameters presented here were consistent with values reported in the literature, shortcomings in the total mass exist (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Jensen and Fletcher, 1994; Muri et al., 2008; Pearsall et al., 1996). The mean summed SL to represent patient height was 101.49% (.61%). However, the mean summed SM, assuming equal dominant and non-dominant limbs was 94.03% (.93%). This shortcoming can be contributed to several factors. Both the hands and feet were excluded from this analysis. Additionally, with the delineations utilized in the biomechanics literature, several pieces of the body are ignored (de Leva, 1996). These sections were ignored in the current study to remain consistent with previous literature and allow for comparisons. A section of the thigh located superior to the hip joint center and lateral to the line dissecting the trunk segment from the thigh segment was ignored. This portion would have accounted for less than 1% of total body mass in non-obese individuals and slightly more in obese individuals. A portion of the pelvis located between the hip joint centers and the intersection of the trunk/thigh dissection line was ignored. This portion would have accounted for 5.48% (.74%) and 4.96% (.77%) of the total body mass in non-obese and obese groups, respectively.

Additional limitations of this study should be considered. Whole body DXA scans were performed in the frontal plane only, resulting in unknown COM and k in the sagittal and transverse planes. Subjects were imaged in the supine position with the foot rotated slightly inward. This prevented accurate analysis of the foot segment and may have contributed to some soft tissue deformation compared to a vertical position. This deformation should not have affected SL or SM but may have resulted in slight misestimations of COM position and k. Standing may cause soft tissue to shift distally compared to laying supine which could impact the results presented here, especially in the obese group. Race was not considered in this analysis and it may have a significant impact on body segment parameters (Durkin and Dowling, 2003; Gallagher et al., 1997; Okada et al., 1996). This study was mainly (94%) composed of Caucasian individuals, as such variations in race should not have impacted the results greatly.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, age, obesity and gender have a significant impact on segment mass, center of mass and radius of gyration in old and elderly adults. The data presented here can be used to accurately represent the anthropometrics of an aging population. This study underlines the need to consider age, obesity and gender when utilizing anthropometric data sets.

Acknowledgements

Funding and support was provided by The Pittsburgh Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (NIH P30 AG024827) & The University of Pittsburgh CTRC (NIH/NCRR/CTRC Grant 1 UL1 RR024153-01).Special thanks to Dr. S. Greenspan & Donna Medich.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barbosa AR, Souza JM, Lebrão ML, Laurenti R, Marucci MF. Anthropometry of elderly residents in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica. 2005;21:1929–38. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000600043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer JJ, Pavol MJ, Snow CM, Hayes WC. MRI-based body segment parameters of children differ from age-based estimates derived using photogrammetry. J. Biomech. 2007;40:2904–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RF, Clauser CE, McConville JT, Reynolds HM, Young JW. Investigation of the inertial properties of the human body. AMRL TR. 1975:71–137. [Google Scholar]

- Colné P, Frelut ML, Pérès G, Thoumie P. Postural control in obese adolescents assessed by limits of stability and gait initiation. Gait & Posture. 2008;28:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leva P. Adjustments to Zatsiorsky-Seluyanov's segment inertia parameters. J. Biomech. 1996;29:1223–30. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger AM, Stevens JA. The injury problem among older adults: mortality, morbidity and costs. J. Safety Res. 2006;37:519–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster WT. Space requirements of the seated operator. WADC TR. 1955:55–159. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin JL, Dowling JJ. Analysis of body segment parameter differences between four human populations and the estimation errors of four popular mathematical models. J. Biomech. Eng. 2003;125:515–22. doi: 10.1115/1.1590359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher D, Visser M, De Meersman RE, Sepúlveda D, Baumgartner RN, Pierson RN, et al. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: effects of age, gender, and ethnicity. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;83:229–39. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganley KJ, Powers CM. Anthropometric parameters in children: a comparison of values obtained from dual energy x-ray absorptiometry and cadaver-based estimates. Gait & Posture. 2004;19:133–40. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(03)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2003;4:CD000340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes VA, Roubenoff R, Wood M, Frontera WR, Evans WJ, Fiatarone Singh MA. Anthropometric assessment of 10-y changes in body composition in the elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;80:475–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Mark AE. Separate and combined influence of body mass index and waist circumference on arthritis and knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Obes. 2006;30:1223–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen RK, Fletcher P. Distribution of mass to the segments of elderly males and females. J. Biomech. 1994;27:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Descriptive anthropometric reference data for older Americans. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000;100:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforgia J, Dollman J, Dale MJ, Withers RT, Hill AM. Validation of DXA body composition estimates in obese men and women. Obesity. 2009;17:821–826. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai PP, Leung AK, Li AN, Zhang M. Three-dimensional gait analysis of obese adults. Clin. Biomech. 2008;S1:S2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Koyama A, Li C, Li J, Lu Y, Saeed I, et al. Pelvic body composition measurements by quantitative computed tomography: association with recent hip fracture. Bone. 2008;42:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrangola SL, Madigan ML, Nussbauma MA, Ross R, Davy KP. Changes in body segment inertial parameters of obese individuals with weight loss. J. Biomech. 2008;41:3278–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muri J, Winter SL, Challis JH. Changes in segmental inertial properties with age. J. Biomech. 2008;41:1809–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova GS, Toshev YE. Estimation of male and female body segment parameters of the Bulgarian population using a 16-segmental mathematical model. J. Biomech. 2007;40:3700–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Ae M, Fujii N, Morioka Y. Body segment inertia properties of Japanese elderly. Biomechanism. 1996;13:125–39. [Google Scholar]

- Okosun IS, Chandra KM, Boev A, Boltri JM, Choi ST, Parish DC, et al. Abdominal adiposity in U.S. adults: prevalence and trends, 1960–2000. Prev. Med. 2004;39:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbye T, Dement JM, Krause KM. Obesity and workers' compensation: results from the Duke Health and Safety Surveillance System. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:766–73. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearsall DJ, Reid JG, Livingston LA. Segmental inertial parameters of the human trunk as determined from computed tomography. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1996;24:198–210. doi: 10.1007/BF02667349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GM, Uauy R, Breeze E, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE. Weight, shape, and mortality risk in older persons: elevated waist-hip ratio, not high body mass index, is associated with a greater risk of death. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;84:449–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA. Falls among older adults--risk factors and prevention strategies. J. Safety Res. 2005;36:409–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoudt HW. The anthropometry of the elderly. Human Factors. 1981;23:29–37. doi: 10.1177/001872088102300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Gallagher D, Thornton JC, Yu W, Weil R, Kovac B, Pi-Sunyer FX. Regional body volumes, BMI, waist circumference, and percentage fat in severely obese adults. Obesity. 2007;15:2688–98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. The biomechanics of restricted movement in adult obesity. Obes. Rev. 2006;7:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]