Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the association of benign recurrent vertigo (BRV) and migraine, using standardized questionnaire-based interview of 208 patients with BRV recruited through a University Neurotology clinic. Of 208 patients with BRV, 180 (87%) met the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2004 criteria for migraine: 112 migraine with aura (62%) and 68 without aura (38%). Twenty-eight (13%) did not meet criteria for migraine. Among patients with migraine, 70% experienced headache, one or more auras, photophobia, or auditory symptoms with some or all of their vertigo attacks, meeting the criteria for definite migrainous vertigo. Thirty per cent never experienced migraine symptoms concurrent with vertigo attacks. These met criteria for probable migrainous vertigo. Among patients without migraine, 21% experienced either photophobia or auditory symptoms with some or all of their vertigo attacks; 79% experienced only isolated vertigo. The age of onset and duration of vertigo attacks did not differ significantly between patients with (34 ± 1.2 years) and patients without migraine (31 ± 3.0 years). In patients with migraine, the age of onset of migraine headache preceded the onset of vertigo attacks by an average of 14 years and aura preceded vertigo by 8 years. The most frequent duration of vertigo attacks was between 1 h and 1 day. Benign recurrent vertigo is highly associated with migraine, but a high proportion of patients with BRV and migraine never have migraine symptoms during their vertigo attacks. Other features such as age of onset and duration of vertigo are similar between patients with or without migraine.

Introduction

The term benign recurrent vertigo (BRV) was first introduced by Slater (1) to describe spontaneous attacks of vertigo not explained by either central or otological abnormalities and that did not lead to permanent deficits. This initial case series of seven patients showed a high prevalence of migraine in BRV patients. Subsequent reports have supported an association between vestibular vertigo and migraine, but whether BRV represents a true migraine equivalent has not been definitively settled. BRV is currently not recognized as a migraine equivalent in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn (ICHD-II) (2), although benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood is recognized as one of the periodic syndromes that precede the development of migraine headaches. The most stringent definitions of definite migrainous vertigo proposed by Neuhauser et al. (3) as well as Crevits (4) require spontaneous vertigo attacks that occur concurrently with other migraine features such as headache, photophobia, phonophobia or visual aura. A diagnosis of probable migrainous vertigo can be made, according to criteria by Neuhauser, when vertigo attacks do not occur concurrently with other migraine features in patients with a history of migraine. Several investigators have reported that about one-third of patients who experience migraine headaches and vertigo attacks separately never experience the two together (5–7). However, only one study systematically looked at migraine symptoms other than headache during vertigo attacks. In Neuhauser’s study of 200 patients recruited from a migraine clinic, 33 met the criteria for migrainous vertigo, of whom 23 experienced photophobia and 12 experienced visual or other auras along with the vertigo (3).

We have previously reported families with BRV and migraine indicating that both syndromes are coheritable (8–10). However, no study has investigated the overall prevalence of migraine in BRV or the prevalence of migraine symptoms other than headache during vertigo attacks in a large group of BRV patients. We therefore studied a large series of patients with BRV in order to examine the prevalence of migraine and the association of an expanded constellation of migraine symptoms other than headache. We further present information on age of onset and duration in order to elucidate the clinical spectrum of the association between BRV and migraine.

Methods

Patients were initially identified through a University Neurotology clinical database as experiencing spontaneous episodes of rotational vertigo. All patients were examined by a senior neurologist (R.W.B.) and had no other central nervous system or otological cause for their spells, such as endolymphatic hydrops or vestibulopathy. Patients were selected for this study if they had experienced at least two attacks of spontaneous rotational vertigo not exclusively triggered by head movement. Patients with hearing loss other than bilateral high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss associated with ageing were excluded. The remaining patients were designated as having BRV.

All interviews were conducted using a standardized questionnaire to determine whether the participants met criteria for migraine headache and aura according to the 2004 ICHD-II (2). Vertigo was not considered an aura symptom for the purposes of this study. Study protocols and questionnaires were approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Clinical features assessed were: sex, age of onset of vertigo attacks, age of onset of migraine and/or aura when applicable, duration of vertigo spells, association of vertigo spells with migraine headache, aura, photophobia and auditory symptoms. Duration reported in this study refers to the actual period of rotational vertigo rather than the recovery period.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis software (SISA; http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/). Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons between patients with and without migraine when comparing sex, associated features with vertigo attacks and the duration of episodic vertigo attacks. Comparisons of age of onset of episodic vertigo, age of onset of migraine and age of onset of aura were made using Student’s t-test.

Results

Of the 208 patients who met our criteria for BRV, 180 (87%) met ICHD-II criteria for migraine (Table 1). Twenty-eight patients (13%) did not meet the criteria for migraine. There was a roughly 4:1 F: M distribution in the migraine group and a roughly 2:1 distribution in the no migraine group.

Table 1.

Clinical profile of 208 patients with benign recurrent vertigo

| No migraine |

Migraine (all) |

MoA |

MA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 28 | % | n = 180 | % | P-value | n = 68 | % | n = 112 | % | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 19 | 68 | 143 | 79 | 0.21 | 52 | 76 | 91 | 81 | 0.45 |

| Male | 9 | 32 | 37 | 21 | 16 | 24 | 21 | 19 | ||

| Age of onset | ||||||||||

| Episodic vertigo (S.E.) | 31 (3.0) | 34 (1.2) | 0.39 | 30 (1.8) | 36 (1.5) | 0.04 | ||||

| Migraine headache (S.E.) | 20 (0.97) | NA | 21 (1.7) | 20 (1.2) | 0.64 | |||||

| Aura (S.E.) | NA | 28 (1.5) | NA | |||||||

| Associated symptoms | ||||||||||

| None (isolated vertigo) | 27 | 96 | 133 | 74 | 0.007 | 51 | 75 | 82 | 73 | 0.86 |

| Migraine headache | 0 | 0 | 85 | 47 | NA | 32 | 47 | 53 | 47 | 1 |

| Visual aura | 0 | 0 | 34 | 19 | NA | 0 | 0 | 34 | 30 | NA |

| Auditory* | 4 | 14 | 50 | 28 | 0.17 | 24 | 35 | 26 | 23 | 0.08 |

| Other aura† | 0 | 0 | 13 | 7 | NA | 0 | 0 | 13 | 12 | NA |

| Photophobia | 2 | 7 | 27 | 15 | 0.38 | 9 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 0.67 |

| Only isolated vertigo attacks | 22 | 79 | 54 | 30 | 2 × 10−6 | 24 | 35 | 30 | 27 | 0.24 |

| Some isolated vertigo attacks | 5 | 18 | 79 | 44 | 0.01 | 27 | 40 | 52 | 46 | 0.43 |

| Never isolated vertigo attacks | 1 | 3 | 47 | 26 | 0.007 | 17 | 25 | 30 | 27 | 0.44 |

Hearing loss, tinnitus, fullness, phonophobia.

Cognitive change, dysarthria, hemi- or bilateral weakness, hemi- or bilateral sensory loss, lack of coordination, tremor.

S.E., standard error of the mean.

Distributions are presented for patients without migraine, all migraine patients, patients with migraine without aura (MoA) and patients with migraine with aura (MA).

Of the 180 migraine patients, 112 met criteria for migraine with aura (MA) (62%) and 68 met criteria for migraine without aura (MoA) (38%). Ninety-nine of the 112 MA patients experienced only visual aura, whereas 13 patients experienced additional auras including: aphasia/confusion (n = 6), dysarthria (n = 3), hemisensory loss (n = 8), hemiparesis (n = 11) and lack of coordination/tremor (n = 2). If vertigo had been included as a migraine symptom, then two patients would have met criteria for basilar migraine.

Twenty-six per cent of patients with migraine and 3% without migraine reported always experiencing an additional symptom other than nausea and imbalance during their vertigo attacks (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.007). The distribution of these symptoms is shown in Table 1. Thirty per cent of patients with migraine and 79% of patients without migraine reported that their vertigo attacks were never associated with any other symptom, other than the nausea and imbalance attributable to the vertigo itself (Fisher’s exact test, P = 2 × 10−6). Forty-four per cent of migraine patients reported experiencing at least two vertigo attacks with migraine-associated symptoms and some in isolation. Therefore, of migraine patients 70% would meet criteria for definite migrainous vertigo and 30% for probable migrainous vertigo.

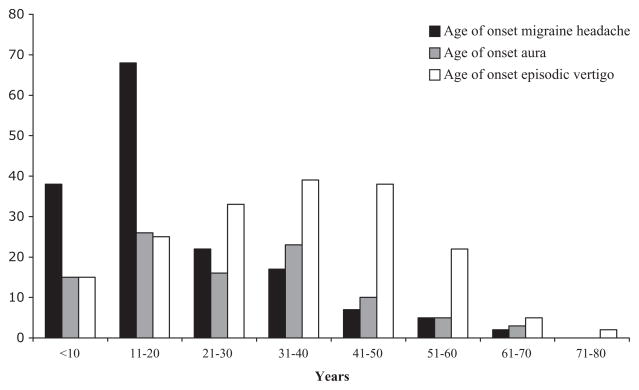

The age of onset of BRV attacks did not differ significantly (t-test, P = 0.39) between patients with (34 ± 1.2 years) and without migraine (31 ± 3.0 years). Dividing the migraine group into MA (36 ± 1.5 years) and MoA (30 ± 1.8 years) showed borderline statistical difference (t-test, P = 0.04). Migraine headaches presented an average of 14 years before the onset of vertigo attacks in patients with migraine; aura presented an average of 8 years before vertigo attacks in MA patients (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Age of onset of migraine headache and aura compared with vertigo attacks in the 180 patients with migraine.

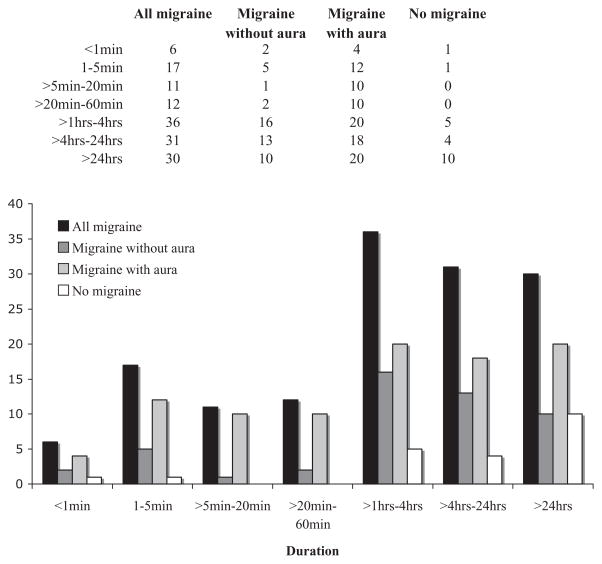

Patients reported how long their typical vertigo attacks lasted according to the following categories: < 1 min, 1–5 min, > 5–20 min, > 20–60 min, > 1–4 h, > 4–24 h and > 24 h. Ninety-four patients with MA (84%), 49 with MoA (72%) and 21 patients with no migraine (75%) reported that their attack durations were predominantly within one of the ranges presented (Fig. 2). We excluded patients who chose multiple durations of attack when comparing the durations across groups in order to use only independent data from each patient. In all groups, the most common duration of attacks was 1 h to 1 day. Fisher’s exact test showed that the duration of vertigo attacks did not differ significantly between patients with migraine and those without migraine (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.2). Dividing the migraine group into MA and MoA also showed no statistical difference either (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.3) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Duration of vertigo attacks in all patients with migraine headaches, migraine without aura (MoA), migraine with aura (MA) or no migraine.

Discussion

The designation of BRV as a migraine equivalent remains an unresolved issue in headache research, but the majority of patients with BRV in our study met criteria for migraine, indicating that the association is not by chance. In some cases, the acceptance of the vertigo attack as a migraine symptom is clear because of the temporal correlation of vestibular symptoms with migraine headaches. In many cases, however, the temporal correlation does not exist, but other features such as duration, associated features and age of onset suggest that vertigo is indeed a migraine equivalent. Supporting this designation is that the largest group of patients with migraine and BRV in our series reported having some vertigo attacks along with other migraine symptoms and some attacks without. A corollary to this situation is the phenomenon of visual auras, which are usually associated with migraine headaches but are well-recognized to occur in isolation and are accepted as a migraine equivalent.

The 62% prevalence of aura seen in our 180 BRV patients with migraine was higher than the rate of aura in unselected migraine patients, which is reported to be about 27–28% (11). Debate exists as to whether MA is a different clinical entity from MoA. Anatomical differences in visual motion processing areas have been seen in both MoA and MA patients (12). Cortical spreading depression emanating from the occipital lobe, which is typically attributed to the aura phase of migraine, has also been seen in a patient in the midst of a migraine attack but with no visual aura (13). Furthermore, migraine preventative medications are helpful in both MA and MoA and may all work by raising thresholds for cortical spreading depression (14), indicating that the mechanism underlying both MoA and MA may be similar. Nevertheless, the rate of heritability of MA seems to be higher than that of MoA (15, 16), and comorbidity with vascular events appears to segregate with MA to a greater degree than MoA, including the risk of small-vessel ischaemic changes in the brain (17, 18). This higher association of MA with vascular disease, particularly in the posterior circulation, may be relevant to why MA patients are more highly represented in our BRV population. Indeed, vasospasm in the posterior circulation has been proposed as a mechanism for migraine-associated damage to the inner ear (19, 20) and may underlie some forms of migrainous vertigo.

Interestingly, there was a higher proportion of men in our BRV patients without migraine, raising the possibility that headache may not be as penetrant in this group. This might be because head pain is sensitive to hormonal fluctuations (21). Therefore, careful assessment should be made regarding other features associated with migraine such as motion sensitivity or a family history of migraine in all patients in order to determine whether these ‘softer’ features may support BRV as a migraine equivalent in a particular patient. Regardless of background, however, age of onset and duration were very similar between all groups in our series. Furthermore, although all ranges of attack durations were seen amongst the entire group of BRV patients, attack durations were largely stereotypical for each patient.

Our study has shown that the majority of patients with BRV have a personal history of migraine. However, even those who do not have such a history occasionally experience migraine features during some or all of their vertigo attacks. Moreover, they have a similar age of onset and duration of vertigo attacks as those with migraine. This raises the question of whether there is a fundamental difference between definite and probable migrainous vertigo or BRV with or without a history of migraine. Because there was a significantly large group of patients who experienced both vertigo spells with migraine features and vertigo spells without, we believe that there may not be a fundamental difference in patients who meet the criteria for definite vs. probable migrainous vertigo.

A significant shortcoming of our study is the lack of a control group that may have been used to determine the rate of migraine in patients without a history of dizziness. However, the prevalence of migraine that we observed was significantly higher than what has been reported as the 1-year population prevalence of migraine in unselected subjects (17.1% for women and 5.6% for men) (22). The rate of migraine in a non-dizzy control group is not likely to have been higher than the overall population prevalence.

As there is no biological marker for dissociating the various kinds of spontaneous dizziness syndromes, it is not known whether episodic feelings of motion sickness, head motion intolerance, oscillopsia or imbalance are the equivalent of rotational vertigo. In the current study, we used a very strict definition of vertigo which required a true hallucination of rotation of the environment. We used this definition to avoid any ambiguity. However, other less distinct descriptions of dizziness may well be pathophysiologically related and may be acceptable operationally.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant P50 DC 05224 from the NIDCD, NIH grant 5 U54 RR019482, and the Clinical Research Training Fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology.

References

- 1.Slater R. Benign recurrent vertigo. JNNP. 1979;42:363–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.42.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuhauser HK, Leopold M, von Brevern M, Arnold G, Lempert T. The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology. 2001;56:436–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crevits L, Bosman T. Migraine-related vertigo: towards a distinctive entity. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayan A, Hood JD. Neurotological manifestations of migraine. Brain. 1984;107:1123–42. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.4.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieterich M, Brandt T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? Neurology. 1999;246:883–92. doi: 10.1007/s004150050478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutrer F, Baloh RW. Migraine-associated dizziness. Headache. 1992;32:300–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1992.hed3206300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh AK, Lee H, Jen JC, Corona S, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Familial benign recurrent vertigo. Am J Med Gen. 2001;100:287–91. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baloh RW, Foster CA, Yue Q, Nelson SF. Familial migraine with vertigo and essential tremor. Neurology. 1996;46:458–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Jen JC, Cha Y, Nelson SF, Baloh RW. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of a large family with migraine associated vertigo. Headache. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01002.x. Epub Dec 11 (ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart WF, Linet MS, Celentano DD, Van Natta M, Ziegler D. Age and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without aura. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1111–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granziera C, DaSilva AF, Snyder J, Tuch DS, Hadjikhani N. Anatomical alterations of the visual motion processing network in migraine with and without aura. PLoS Med. 2006:e402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods RP, Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC. Bilateral spreading cerebral hypoperfusion during spontaneous migraine headache. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1689–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412223312505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayata C, Jin H, Kudo C, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Suppression of cortical spreading depression in migraine prophylaxis. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:652–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen BK. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are two different entities. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:183–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.015003183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell MB, Olesen J. Increased familial risk and evidence of genetic factor in migraine. BMJ. 1995;311:541–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7004.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurth T, Gaziano M, Cook NR, Logroscino G, Diener H-C, Buring J. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2006;296:283–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruit MC, Launer LJ, Ferrari MD, van Buchem MA. Infarcts in the posterior circulation territory in migraine. The population-based MRI CAMERA study. Brain. 2005;128:2068–77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H, Whitman GT, Lim JG, Yi SD, Cho YW, Ying S, Baloh RW. Hearing symptoms in migrainous infarction. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:113–16. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viirre ES, Baloh RW. Migraine as a cause of sudden hearing loss. Headache. 1996;36:24–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3601024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelman L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventative therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]