Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) uses a host cell tRNALys,3 molecule to prime reverse transcription of the viral RNA genome into double-stranded DNA prior to integration into the host genome. All three human tRNALys isoacceptors along with human lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) are selectively packaged into HIV-1. Packaging of LysRS requires the viral Gag polyprotein and incorporation of tRNALys additionally requires the Gag-Pol precursor. A model that incorporates the known interactions between components of the putative packaging complex is presented. The molecular interactions that direct assembly of the tRNALys/LysRS packaging complex hold promise for the development of new anti-viral agents.

Keywords: tRNA packaging; HIV-1 assembly; capsid, Gag; Gag-Pol; lysyl-tRNA synthetase

Introduction

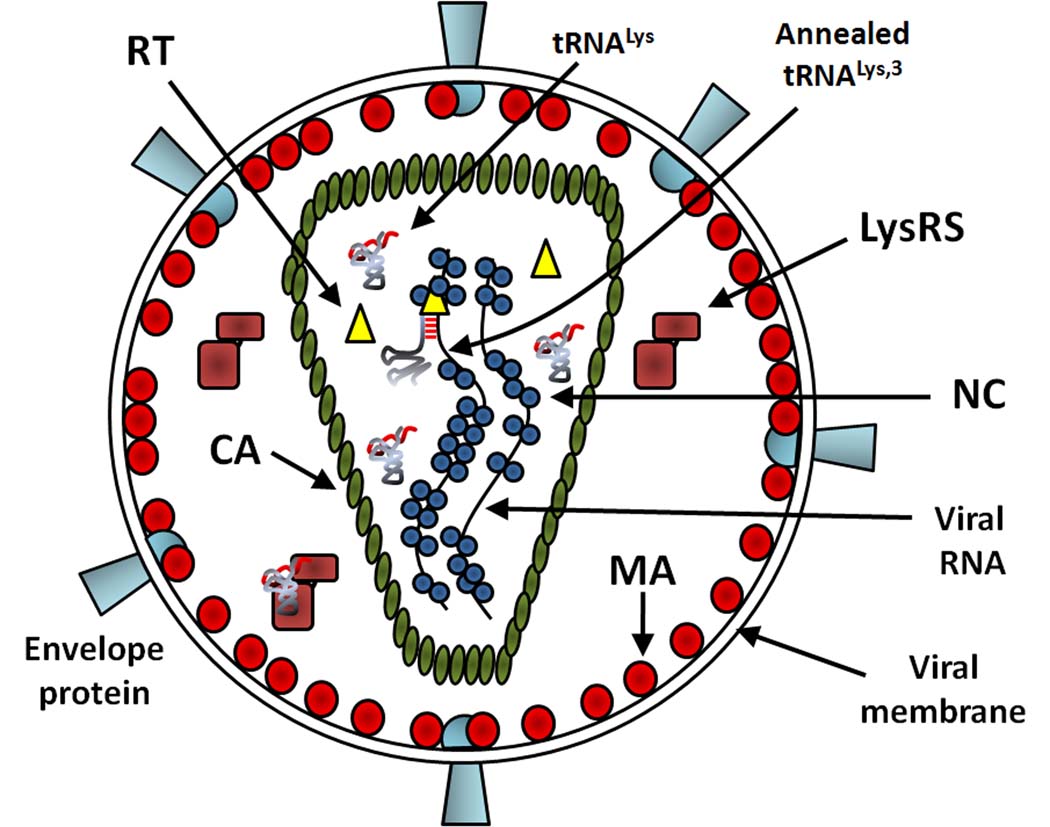

During the replication of human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), the viral RNA genome is converted into double-stranded proviral DNA during reverse transcription. Initiation of reverse transcription is primed by a cellular tRNA, tRNALys,3, which is selectively incorporated into the virus during its assembly. Figure 1A shows the components of HIV-1. The virus particle is surrounded by membrane derived from the cell plasma membrane (PM) during viral budding. Proteins comprising the viral structure include the glycosylated envelope proteins and mature structural proteins resulting from the proteolytic processing of the Gag precursor protein: matrix (MA), underlying the membrane; capsid (CA), comprising the wall of the core, within which are two strands of viral RNA genome; and nucleocapsid (NC), binding to the viral RNA. Additionally, three virally-encoded enzymes used during the HIV-1 lifecycle are protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN). PR and IN (not shown in Figure 1A) form homodimers or homotetramers while RT is a heterodimer. They are created upon processing of the Gag-Pol precursor protein by viral PR.

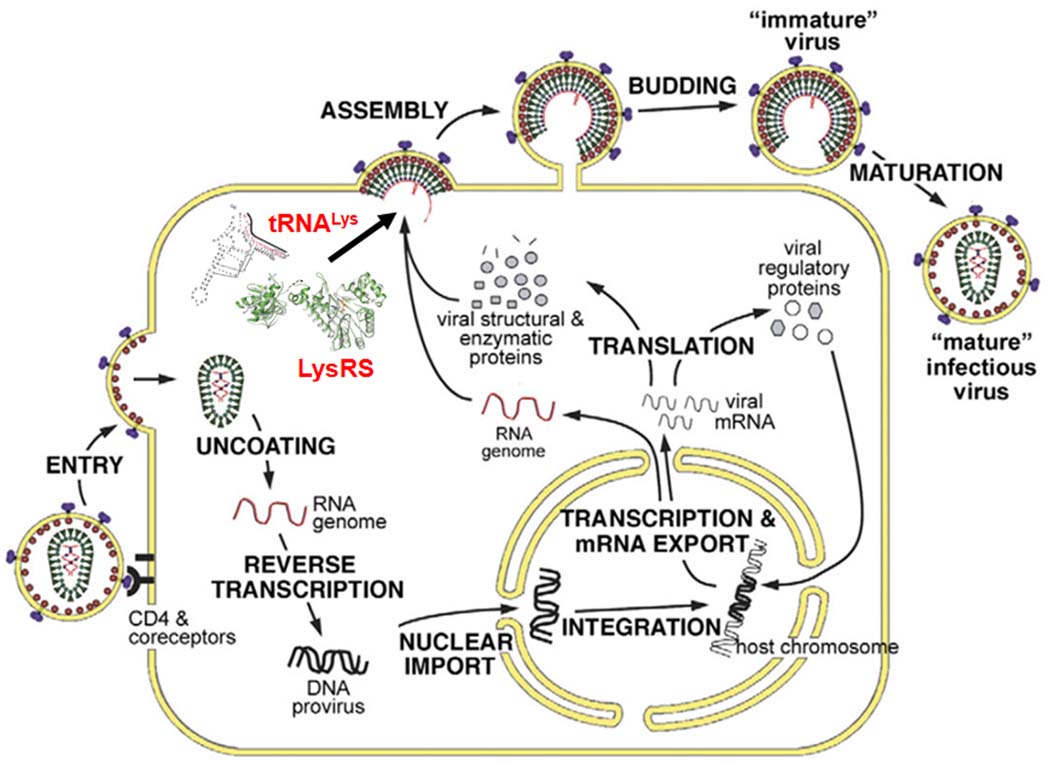

Figure 1.

Cartoons showing the mature HIV-1 virion and HIV-1 lifecycle. (A) Schematic of the mature virus structure. MA is shown binding the virus membrane and CA forms the core, within which NC is bound to two copies of the viral genomic RNA. Inside the core, tRNALys,3 is shown annealed to the genome. Whether free or tRNA-bound LysRS is found in the core is not known. (B) Scheme of HIV-1 life cycle adapted from [83]. Assembly is a complex process that occurs at the PM and results in budding and maturation of new virions. During assembly, LysRS and tRNALys are packaged by the Gag and Gag-Pol viral proteins.

The replication cycle of HIV-1 is shown in Figure 1B (for review, see [1]). Briefly, HIV-1 envelope proteins bind to PM receptors of the target cell, resulting in fusion of viral and cell membranes. Upon its release into the cytoplasm, the CA core disassembles, and within the resulting nucleoprotein complex, the viral RNA genome is copied into a double-stranded cDNA by RT. The tRNA primer, which is annealed to the genomic RNA primer binding site (PBS), initiates reverse transcription [2], a complex process involving multiple strand-transfer reactions facilitated by the NC protein, a nucleic acid chaperone [3]. The resultant double-stranded viral DNA within the pre-integration complex is translocated into the nucleus of the infected cell where it integrates into the host cell’s DNA and codes for viral mRNA and proteins. Envelope protein and regulatory proteins are coded for by spliced mRNAs, while both Gag and Gag-Pol are translated from full-length viral RNA, which is packaged into assembling virions where it serves as viral genomic RNA.

The Gag and Gag-Pol proteins assemble at the PM, and during or immediately after budding from the cell, the viral PR is activated and cleaves the precursor proteins into the mature products shown in Figure 1A. A number of host cell factors are packaged during the viral assembly step, including the tRNALys primer. Transfer RNAs are known to participate in a channeled life cycle in mammalian cells, and are virtually never free [4]. For this reason, the primer tRNA cannot be selected from the microenvironment and must be present in the mature CA core prior to initiation of reverse transcription, which may initiate prior to capsid disassembly [5,6]. Thus, during virus assembly, viral genomic RNA and cellular tRNALys isoacceptors (tRNALys,3 and tRNALys,1,2) are selectively concentrated at the site of assembly. A portion of the incorporated tRNALys is annealed near the 5´ end of the viral RNA to the 18-nucleotide PBS sequence, which is perfectly complementary to the 3´-18 nucleotides of tRNALys,3. It is not known whether tRNA annealing occurs prior to, or after, viral budding.

In lentiviruses, including HIV-1, tRNALys,3 serves as the primer tRNA [7]. However, in avian retroviruses, tRNATrp is the primer for all members of the avian sarcoma and leucosis virus group examined to date [8,9], whereas tRNAPro is the common primer for murine leukemia virus (MuLV) [10]. “Selective packaging of tRNA” refers to the increase in the percentage of the low molecular weight RNA population representing primer tRNA in going from the cytoplasm to the virus. For example, in avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV), the relative concentration of tRNATrp changes from 1.4% to 32% [9]. In HIV-1 produced from COS7 cells transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA, both primer tRNALys,3 and the other major tRNALys isoacceptors, tRNALys,1 and tRNALys,2, are selectively packaged. The relative concentration of tRNALys changes from 5–6% in the cytoplasm to 50–60% in the virus [11]. tRNALys,1,2, which differs from tRNALys,3 by 14 or 16 bases, represents two tRNALys isoacceptors differing by one base pair in the anticodon stem. While not involved in functioning as a primer in HIV-1, evidence has been found suggesting that tRNALys,1,2 may play a role in the import of the pre-integration complex into the nucleus of the infected cell [12]. In MuLV, selective packaging of primer tRNAPro is less dramatic, going from a relative cytoplasmic concentration of 5–6% to 12–24% of low molecular weight RNA [9]. The selective concentration of tRNALys is required for optimizing both annealing and infectivity of the HIV-1 population [13], and an understanding of this process requires an understanding of how viral RNA, tRNALys, and viral and cellular proteins interact during HIV-1 assembly.

Gag/Gag-Pol assembly

Gag alone is capable of forming extracellular Gag viral-like particles (VLPs), but this assembly requires RNA for its formation, and in the absence of genomic RNA, cellular RNA can perform this function [14–17]. It is generally assumed that Gag forms multimeric complexes at cell membranes (PM or endosomal [18]), but a pre-membrane formation of smaller Gag complexes containing genomic RNA has not been excluded. Genomic RNA is packaged through interactions between NC protein sequences in Gag with specific stem/loop structures at the 5´ end of the genomic RNA [19,20]. A potential role for MA, another nucleic acid binding domain, has also been proposed [21,22]. The in vivo interaction of Gag with Gag-Pol has also been well documented [23,24], and it is believed that Gag-Pol is carried into the assembling particle by interaction with CA and spacer peptide-1 (SP1) domains of Gag [25]. Cryoelectron microscopy has indicated that in immature virions, Gag is radially distributed with the N-terminal sequences within the MA domain associated with membrane, and the C-terminal sequences coding for SP1-NC-spacer peptide 2 (SP2)-p6 domains nearest the center of the virion [26,27]. Images of immature virions have suggested that Gag molecules may be arranged in interacting hexagonal bundles, with a Gag molecule at each vertex of the hexagon [28–31], a model supported by workstudying the in vitro assembly of Gag [32]. The hexagonal order, however, appears to be primarily at the level of CA and SP1, and the N- or C-terminal regions of Gag are largely disordered [28–31], supporting the conclusion that Gag/Gag interactions occur primarily at the CA/SP1 region.

tRNALys incorporation into HIV-1

Selective tRNALys packaging into HIV-1 occurs independent of the genomic RNA [11]. Gag-Pol is required for packaging tRNALys into Gag VLPs or into HIV-1 [11], and more specifically, the thumb (TH) structural domain in RT plays an important role in the interaction between Gag-Pol and tRNALys [33]. Although Gag-Pol appears to play a role in stable incorporation of tRNALys, it is believed that Gag is responsible for selecting tRNALys isoacceptors for incorporation into VLPs. This selection is not direct but is mediated through specific interactions with the tRNALys binding protein, human lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) [34–37]. LysRS is responsible for binding and aminoacylating all three tRNALys isoacceptors that are found in HIV-1 particles [38]. Gag alone is sufficient for incorporation of LysRS into Gag VLPs [38], but as mentioned earlier, Gag-Pol is required for tRNALys incorporation as well [11]. Moreover, the packaging of tRNALys isoacceptors requires interaction with LysRS [39] but not aminoacylation of the tRNA [40].

The interaction of Gag with LysRS is specific, i.e., of 9 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) and 3 related proteins tested, only LysRS is packaged into HIV-1 [41]. The domains critical for the interaction have been mapped to include the so-called motif 1 domain of LysRS and the C-terminal domain of CA [34]. Deletions that extend into either of these domains abolish the interaction in vitro and, importantly, eliminate packaging of LysRS into Gag VLPs [34]. Interestingly, both of these primarily helical regions are responsible for homodimerization of their respective proteins. An equilibrium binding constant of 310 nM was measured for the Gag/LysRS interaction in vitro, and CA alone binds to LysRS with a similar affinity (~400 nM) as full-length Gag [35,36]. Mutant Gag and LysRS that do not homodimerize still interact, suggesting that dimerization of each protein per se is not required for the interaction, even though amino acids proximal to regions involved in forming the homodimer interfaces contribute to heterodimer formation. Gel chromatography studies further support the formation of a Gag/LysRS heterodimer in vitro. It is not known, however, if Gag interacts in vivo with the monomeric, dimeric, or tetrameric state of LysRS [42].

Newly synthesized LysRS is the source of viral LysRS, which likely interacts with Gag before entering its identified steady-state cellular compartments (high molecular weight multisynthetase complex (MSC), nuclei, mitochondria, cell membrane) [41,43]. Importantly, siRNA knockdown of newly synthesized LysRS (80%) results in similarly reduced levels of tRNALys packaging, tRNALys,3 priming by reverse transcriptase, and viral infectivity [43]. It has also been reported that mitochondrial LysRS (mLysRS) is a source of viral LysRS [37,44]. In human cells, cytoplasmic LysRS (cLysRS) and mLysRS are encoded from the same gene by means of alternate splicing. The two LysRS species share 576 identical amino acids, but mLysRS has a different N-terminus of 49 amino acids that contains a putative mitochondrial targeting sequence [45]. In HIV-1 produced from U937 cells, antibodies directed to full-length LysRS detected full-length and truncated species, while antibodies specific for the unique N-termini of cLysRS and mLysRS were only able to detect mLysRS. These data support the conclusion that mLysRS is a source of viral LysRS [37]. However, the conclusion that mLysRS is the sole source of viral LysRS contradicts several reports in which expression of exogenous cLysRS in transfected HIV-1 producing cells results in cLysRS incorporation [13,34,40,46]. This enhancement in LysRS packaging is associated with increases in tRNALys packaging, tRNALys,3 annealing, and viral infectivity [13]. We suggest that the inability to detect cLysRS in virions using antibodies directed to the N-terminus may be associated with the lability of the N-terminus of cLysRS [38]. In vitro mapping studies also support the possibility that both forms of LysRS are possible sources for viral packaged LysRS, as the region of interaction with Gag is the motif 1 dimer interface present in both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic forms of the synthetase [35,36].

Formation of the tRNALys packaging complex

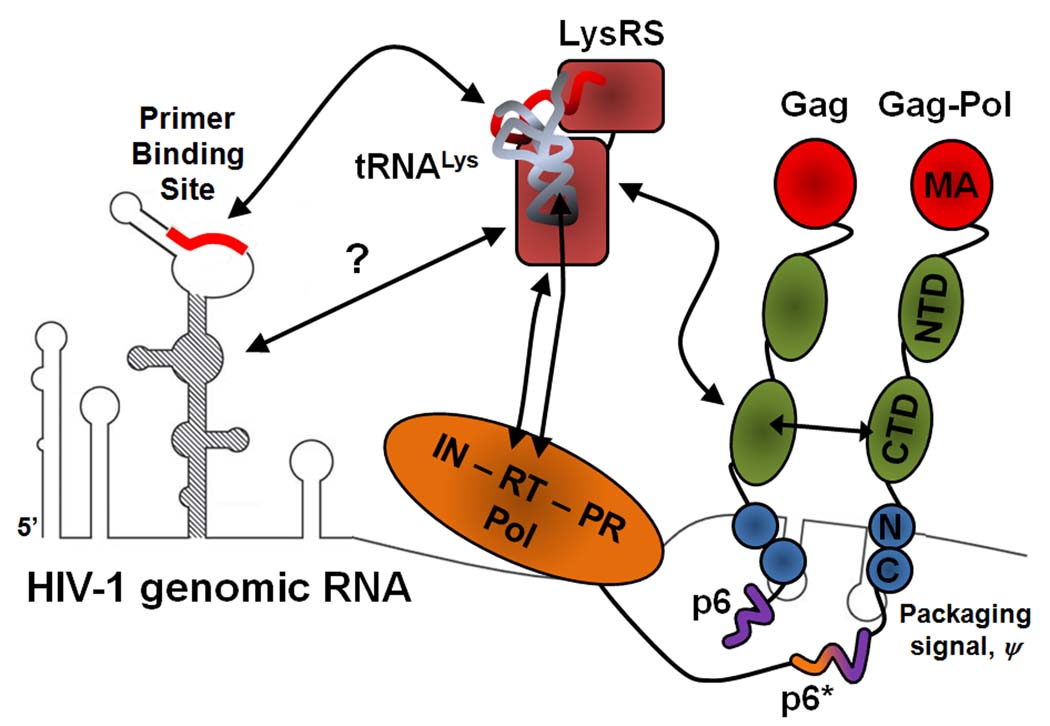

While tRNALys is targeted for incorporation into HIV-1 by a specific interaction of HIV-1 Gag with LysRS, RT sequences within Gag-Pol must also be present, or LysRS will be packaged without tRNALys [33,38]. Predicted relationships within the putative tRNALys packaging complex are schematically shown in Figure 2, along with the mature proteinsequences coded for by the Gag and Gag-Pol precursors. In Figure 2, a Gag/Gag-Pol/viral RNA complex interacts with a tRNALys,3/LysRS complex, with Gag binding specifically to LysRS, and tRNALys,3 binding to RT domain in Gag-Pol. In the virus, tRNALys,3 is uncharged (i.e., has a free 3´ hydroxyl group on the ribose of the terminal adenosine) [47], and must be in this state in order to act as a primer for RT. It is not known if tRNALys,3 is uncharged at the time of these interactions, or if the interaction of Gag with LysRS facilitates deacylation and release of tRNALys from the synthetase. In vitro studies have shown that the presence of Gag inhibits aminoacylation by human LysRS but does not promote deacylation of Lys-tRNALys (R. Kennedy. M. Hong, and K. Musier-Forsyth, unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the interactions that may occur within the LysRS/tRNALys packaging complex. A single copy of each molecule is shown for simplicity. The Gag protein interacts with LysRS via the CA C-terminal domain (CTD) and Pol interactions (RT domain) with LysRS have also been reported to play a role in vivo. The RT domain of Pol also interacts with tRNALys and may help to position tRNALys,3 for annealing onto the PBS. CA-CTD/CA-CTD interactions occur between Gag proteins and between Gag and Gag-Pol. The highly basic NC protein contacts the viral RNA packaging signal, and additional contacts between the viral RNA and LysRS may also occur. The RNA secondary structure proximal to the PBS is taken from [84].

Based on the following data, we predict that the Gag/Gag-Pol ratio in the tRNALys packaging complex is lower than the ratio present in the budding virion. When transfected 293T cells producing HIV-1 are pulsed for 10 min with 35S-Cys/Met, ~15% of newly-synthesized Gag and >95% of newly-synthesized Gag-Pol are found associated with membrane domains enriched in lipid rafts [48], a membrane microdomain from which HIV-1 is proposed to bud [49,50]. The Gag and Gag-Pol molecules at this membrane domain are presumably interacting since the movement of Gag-Pol to membrane requires association with Gag, which is driven by the interaction between homologous Gag sequences within Gag and Gag-Pol [23,51]. Since the ratio of synthesis of Gag/Gag-Pol in cells has been estimated to be approximately 20:1 [52], the ratio of newly-synthesized Gag:Gag-Pol at lipid raft domains would be 3:1—much lower than the Gag:Gag-Pol ratio found in immature virions. It was observed that during a 30-min chase period, more Gag molecules moved towards lipid raft-enriched membrane [48], implying that the tRNALys,3 packaging/annealing complex may represent a very early assembly intermediate to which more Gag is later added. However, this assembly intermediate has not been directly detected.

In such an assembly intermediate, Gag-Pol may be present as a dimer, which is required for later Gag and Gag-Pol processing [53]. Gag and Gag-Pol would be present in a 3:1 ratio. LysRS may be present as a monomer since monomeric LysRS has been shown to interact with monomeric Gag in vitro [36]. However, as mentioned earlier the oligomeric state of LysRS upon interaction with Gag in vivo is not known. Gag-Pol may adopt a conformation to interact with Gag, reminiscent of the intermolecular interaction between Pol and Gag in human foamy viruses [54]. Expression of HIV-1 Pol and Gag from separate plasmids in 293T cells results in the incorporation of Pol into Gag VLPs, and Pol can replace Gag-Pol in facilitating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into the Gag VLPs [55]. Recent reports also indicate that RT sequences alone can be incorporated into Gag VLPs, with apparent interactions occurring between MA and p6 sequences in Gag and the TH domain in RT [56,57].

The association of Gag-Pol with Gag is most likely driven by an interaction between homologous Gag sequences in both molecules, and the model in Figure 2 shows the additional interactions that have been proposed to date. The model shows tRNALys,3 bound to TH in RT, which is based both on in vitro studies on the interaction of purified HIV-1 RT with tRNALys,3 [58,59], and in vivo studies on the effect of C-terminal deletions in Gag-Pol upon tRNALys,3 incorporation into HIV-1 [33,60]. The model also shows the 5´ region of viral genomic RNA. HIV-1 genomic RNA is packaged into the virus through interactions between NC sequences in Gag and specific stem/loop structures at the 5´ end of the genomic RNA [19,20]. The PBS is located within 100 nucleotides upstream of these sequences. Additional interactions between LysRS and genomic RNA proximal to the PBS may also facilitate tRNA targeting and placement (C. Jones, J., Saadatmand, L. Kleiman, and K. Musier-Forsyth, unpublished data). During viral maturation, the first PR cleavage is between SP1 and NCp7 [61]. An interaction between Pol and Gag could insure that Pol is retained in the partially closed budding particle if proteolytic cleavage initiates during assembly. The fact that p6 is required for the interaction of Gag with Pol is of interest in this context since it has been reported that the deletion of p6 from Gag resulted in a lower concentration of Pol products in PR-positive HIV-1, but no change in Gag-Pol incorporation in PR-negative viruses [62].

The model in Figure 2 suggests that an interaction between LysRS and Pol sequences might facilitate formation of the complex. In support of this model, an interaction between LysRS and the connection domain (CD)/RNaseH domains in RT has been reported [57]. LysRS and mature RT do not interact in vitro (T. Stello, L. Kleiman, and K. Musier-Forsyth, unpublished data), and thus, this interaction may only occur in the context of Pol or may be indirect, and the function of this interaction is not yet clear. Since C-terminal deletions of Gag-Pol that include the RT CD do not inhibit tRNALys,3 packaging [60], the LysRS/RT interaction is not involved in facilitating tRNALys,3 packaging. On the other hand, virions in which Gag-Pol is C-terminally deleted through the RT CD do not contain annealed tRNALys,3. This could mean that a Gag/LysRS/RT interaction may be involved in conformational changes facilitating movement of tRNALys,3 towards the PBS.

In summary, based on the current estimates of ~2500 Gag molecules in immature HIV-1 particles [31,63,64], we estimate that within the tRNALys packaging complex, an early assembly intermediate, there may be approximately 300 molecules of Gag, 100 molecules of Gag-Pol, 25 molecules of LysRS [65], and 20–25 molecules of tRNALys [47] in addition to viral genomic RNA. Our model in Figure 2 indicates that Gag-Pol, LysRS and tRNALys,3 should be proximal to the Gag molecule(s) that are chaperoning tRNA annealing (see below), in order to facilitate transfer of tRNALys,3 from LysRS to the PBS, via RT. Ongoing studies are aimed at understanding whether additional interactions between LysRS and genomic RNA help to target this complex to the PBS region.

When does annealing of tRNALys,3 to viral RNA occur?

Previous in vitro studies have shown HIV-1 NC to be a very effective nucleic acid chaperone protein that facilitates nucleic acid remodeling events throughout the reverse transcription process [66]. Although NC can efficiently catalyze tRNALys,3 annealing onto the PBS in vitro [67], in viruses lacking active PR, tRNA annealing to the PBS still occurs, suggesting that the precursor protein Gag may act as a NA chaperone and facilitate this process in vivo [68,69]. Indeed, Gag p6, which lacks the C-terminal p6 domain, and other assembly-competent Gag variants have been demonstrated to facilitate tRNA annealing and genome dimerization in vitro [70,71]. New studies also show that Gag’s chaperone activity is stimulated upon interacting with inositol phosphates in the PM (C. Jones, S. Datta, A. Rein, I. Rouzina, and K. Musier-Forsyth, submitted).

While it has been demonstrated that the selective packaging of primer tRNALys,3 into HIV-1 is correlated with achieving optimal annealing of tRNALys,3 and infectivity of the HIV-1 population [13], it is not known whether selective packaging of tRNALys,3 is required for annealing. That is, selective packaging of tRNALys,3 into the virus may be due to a higher local concentration of tRNA at the site of viral assembly, where annealing may take place prior to viral budding. It has been shown that tRNALys,3 annealed in vivo or in vitro to viral RNA by Gag has a reduced ability to initiate reverse transcription [72] and results in a less stably annealed state relative to tRNALys,3 annealed by NC [69]. This reduced ability of Gag-annealed tRNALys,3 to function as a primer for reverse transcription can be rescued by a transient exposure of total viral RNA isolated from PR-negative virions to NC. Taken together, these data suggest that tRNALys,3 annealing may be a two-step process, involving an initial Gag-facilitated annealing at the site of viral assembly, followed by a re-annealing by NC after protein processing. Alternatively, NC may chaperone the refolding of viral RNA into an alternative structure to the one stabilized by Gag. Evidence for an RNA structural change that could govern RT initiation has been described [73].

Future Prospects

Understanding the mechanism by which the tRNA packaging complex is targeted to the 5´ region of the genomic RNA, and probing the timing of tRNA annealing in the viral lifecycle are just two of the open questions currently under investigation. Gag interacts with viral genomic RNA and the PM, but Gag’s interactions with other host cell factors such as LysRS, ABCE1, cyclophilin A, Tsg101, and ALIX are also critical to virus infectivity [38,74–77]. Interaction with so many cellular factors may be achieved by distinct pools of Gag, each interacting with separate essential factors and ultimately mixing during assembly at the PM. How newly synthesized LysRS is diverted from its normal function in translation to interact with HIV components is not known, but one of the cellular pools of Gag presumably recruits LysRS from its normal role in translation to aid virus replication. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases have been shown to function in a wide array of cellular processes that are distinct from aminoacylation [78]. The expanded functions of synthetases and other components of the MSC have been shown to be regulated at the level of posttranslational modification. For example, in the case of human glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase (EPRS), phosphorylation is required for its release from the MSC and for formation of the heterotetrameric γ-interferon-activated inhibitor of translation (GAIT) complex [79–81]. Recently, specific phosphorylation of human LysRS has been shown to regulate Ap4A production in response to immunological challenge [82]. Phosphorylation results in release of LysRS from the MSC, enhanced Ap4A synthesis, and transcriptional activation via interaction with MITF [82]. While we do not yet know the phosphorylation state of LysRS that is incorporated into HIV, one intriguing possibility is that HIV infection triggers posttranslational modifications that modulate the oligomerization state of LysRS and/or LysRS-protein interactions.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- MA

matrix protein

- CA

capsid protein

- NC

nucleocapsid protein

- PR

protease

- RT or

reverse transcriptase

- IN

integrase

- PBS

primer binding site

- MuLV

murine leukemia virus

- AMV

avian myeloblastosis virus

- aaRSs

aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

- LysRS

lysyl-tRNA synthetase

- RSV

Rous sarcoma virus

- SP1

spacer peptide-1

- SP2

spacer peptide-2

- SL3

stem-loop 3

- CD

connection domain

- TH

thumb domain

- VLP

virus-like particle

- MSC

multisynthetase complex

- PM

plasma membrane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus H. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mak J, Kleiman L. Primer tRNAs for reverse transcription. J Virol. 1997;71:8087–8095. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8087-8095.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin JG, Guo J, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: critical role in reverse transcription and molecular mechanism. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;80:217–286. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negrutskii BS, Deutscher MP. Channeling of Aminoacyl-tRNA for Protein Synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:4991–4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lori F, Veronese F, De Vico AL, Lusso P, Reitz MJ, Gallo RC. Viral DNA Carried by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Virons. J Virol. 1992;66:5067–5074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5067-5074.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Dornadula G, Pomerantz RJ. Natural endogenous reverse transcription of HIV-1. J Reprod Immunol. 1998;41:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(98)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratner L, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada F, Sawyer RC, Dahlberg JE. A primer RNA for initiation of In vitro Rous Sarcoma Virus DNA synthesis: Nucleotide sequence and amino acid acceptor activity. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:3487–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters LC, Mullin BC. Transfer RNA in RNA tumor viruses. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1977;20:131–160. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters G, Harada F, Dahlberg JE, Panet A, Haseltine WA, Baltimore D. Low-molecular-weight RNAs of Moloney murine leukemia virus: Identification of the primer for RNA-directed DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1977;21:1031–1041. doi: 10.1128/jvi.21.3.1031-1041.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mak J, Jiang M, Wainberg MA, Hammarskjold M-L, Rekosh D, Kleiman L. Role of Pr160gag-pol in mediating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1994;68:2065–2072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2065-2072.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaitseva L, Myers R, Fassati A. tRNAs promote nuclear import of HIV-1 intracellular reverse transcription complexes. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabor J, Cen S, Javanbakht H, Niu M, Kleiman L. Effect of altering the tRNALys3 concentration in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon its annealing to viral RNA, GagPol incorporation, and viral infectivity. J Virol. 2002;76:9096–9102. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9096-9102.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell S, Vogt VM. Self-Assembly In Vitro of Purified CA-NC Proteins from Rous Sarcoma Virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6487–6497. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Krausslich HG. In vitro assembly properties of purified bacterially expressed capsid proteins of human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khorchid A, Halwani R, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. Role of RNA in facilitating Gag/Gag-Pol Interaction. J Virol. 2002;76:4131–4137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.4131-4137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muriaux D, Mirro J, Harvin D, Rein A. RNA is a structural element in retrovirus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5246–5251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono A, Freed EO. Cell-type-dependent targeting of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly to the plasma membrane and the multivesicular body. J Virol. 2004;78:1552–1563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1552-1563.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkowitz R, Fisher J, Goff SP. RNA packaging. In: Krausslich HG, editor. Morphogenesis and maturation of retroviruses. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geigenmüller U, Linial ML. Specific Binding of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Gag-Derived Proteins to a 5' HIV-1 Genomic RNA Sequence. J Virol. 1996;70:667–671. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.667-671.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Norris KM, Mansky LM. Involvement of the matrix and nucleocapsid domains of the bovine leukemia virus Gag polyprotein precursor in viral RNA packaging. J Virol. 2003;77:9431–9438. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9431-9438.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ott DE, Coren LV, Gagliardi TD. Redundant roles for nucleocapsid and matrix RNA-binding sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J Virol. 2005;79:13839–13847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13839-13847.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Morrow CD. The nonmyristylated Pr160gag-pol polyprotein of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 interacts with Pr55gag and is incorporated into virus-like particles. J Virol. 1992;66:6304–6313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6304-6313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AJ, Cho MI, Hammarskjöld ML, Rekosh D. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Pr55gag and Pr160gag-pol expressed from a simian virus 40 late replacement vector are efficiently processed and assembled into virus-like particles. J Virol. 1990;64:2743–2750. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2743-2750.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srinivasakumar N, Hammarskjöld M-L, Rekosh D. Characterization of deletion mutations in the capsid region of HIV-1 that affect particle formation and Gag-Pol precursor incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:6106–6114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6106-6114.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller SD, Wilk T, Gowen BE, Krausslich H-G, Vogt VM. Cryoelectron microscopy reveals ordered domains in the immature HIV-1 particle. Current Biology. 1997;7:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilk T, et al. Organization of immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:759–771. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.759-771.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs JA, Johnson MC, Simon MN, Fuller SD, Vogt VM. Cryoelectron microscopy reveals conserved and divergent features of gag packing in immature particles of Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayo K, Huseby D, McDermott J, Arvidson B, Finlay L, Barklis E. Retrovirus capsid protein assembly arrangements. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nermut MV, Hockley DJ, Bron P, Thomas D, Zhang WH, Jones IM. Further evidence for hexagonal organization of HIV gag protein in prebudding assemblies and immature virus-like particles. J Struct Biol. 1998;123:143–149. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright ER, Schooler JB, Ding HJ, Kieffer C, Fillmore C, Sundquist WI, Jensen GJ. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. Embo J. 2007;26:2218–2226. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huseby D, Barklis RL, Alfadhli A, Barklis E. Assembly of human immunodeficiency virus precursor gag proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17664–17670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khorchid A, Javanbakht H, Parniak MA, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. Sequences within Pr160gag-pol affecting the selective packaging of tRNALys into HIV-1. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:17–26. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Javanbakht H, Halwani R, Cen S, Saadatmand J, Musier-Forsyth K, Gottlinger H, Kleiman L. The interaction between HIV-1 Gag and human lysyl-tRNA synthetase during viral assembly. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27644–27651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovaleski BJ, Kennedy R, Khorchid A, Kleiman L, Matsuo H, Musier-Forsyth K. Critical role of helix 4 of HIV-1 capsid C-terminal domain in interactions with human lysyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32274–32279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kovaleski BJ, Kennedy R, Hong MK, Datta SA, Kleiman L, Rein A, Musier-Forsyth K. In vitro characterization of the interaction between HIV-1 Gag and human lysyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19449–19456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminska M, Shalak V, Francin M, Mirande M. Viral hijacking of mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetase. J Virol. 2007;81:68–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01267-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cen S, Khorchid A, Javanbakht H, Gabor J, Stello T, Shiba K, Musier-Forsyth K, Kleiman L. Incorporation of lysyl-tRNA synthetase into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:5043–5048. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5043-5048.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Javanbakht H, Cen S, Musier-Forsyth K, Kleiman L. Correlation between tRNALys3 aminoacylation and incorporation into HIV-1. JBiol Chem. 2002;277:17389–17396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cen S, Javanbakht H, Niu M, Kleiman L. Ability of wild-type and mutant lysyl-tRNA synthetase to facilitate tRNALys incorporation into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2004;78:1595–1601. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1595-1601.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halwani R, Cen S, Javanbakht H, Saadatmand J, Kim S, Shiba K, Kleiman L. Cellular distribution of Lysyl-tRNA synthetase and its interaction with Gag during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J Virol. 2004;78:7553–7564. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7553-7564.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo M, Ignatov M, Musier-Forsyth K, Schimmel P, Yang XL. Crystal structure of tetrameric form of human lysyl-tRNA synthetase: Implications for multisynthetase complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:2331–2336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712072105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo F, Cen S, Niu M, Javanbakht H, Kleiman L. Specific inhibition of the synthesis of human lysyl-tRNA synthetase results in decreases in tRNALys incorporation, tRNALys annealing to viral RNA, and viral infectivity in HIV-1. J Virol. 2003;77:9817–9822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9817-9822.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaminska M, Francin M, Shalak V, Mirande M. Role of HIV-1 Vpr-induced apoptosis on the release of mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3105–3110. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tolkunova E, Park H, Xia J, King MP, Davidson E. The human lysyl-tRNA synthetase gene encodes both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial enzymes by means of an unusual alternative splicing of the primary transcript. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35063–35069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo F, Gabor J, Cen S, Hu K, Mouland AJ, Kleiman L. Inhibition of cellular HIV-1 protease activity by lysyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26018–26023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang Y, Mak J, Cao Q, Li Z, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. Incorporation of excess wild type and mutant tRNALys3 into HIV-1. J Virol. 1994;68:7676–7683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7676-7683.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halwani R, Khorchid A, Cen S, Kleiman L. Rapid localization of Gag/GagPol complexes to detergent-resistant membrane during the assembly of HIV-1. J Virol. 2003;77:3973–3984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.3973-3984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen DH, Hildreth JE. Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J Virol. 2000;74:3264–3272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3264-3272.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ono A, Freed EO. Plasma membrane rafts play a critical role in HIV-1 assembly and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13925–13930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241320298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith AJ, Srivivasakumar N, Hammarskjöld M-L, Rekosh D. Requirements for incorporation of Pr160gag-pol from Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 into virus-like particles. J Virol. 1993;67:2266–2275. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2266-2275.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gendron K, Charbonneau J, Dulude D, Heveker N, Ferbeyre G, Brakier-Gingras L. The presence of the TAR RNA structure alters the programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift efficiency of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by modifying the rate of translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:30–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettit SC, Gulnik S, Everitt L, Kaplan AH. The dimer interfaces of protease and extra-protease domains influence the activation of protease and the specificity of GagPol cleavage. J Virol. 2003;77:366–374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.366-374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stenbak CR, Linial ML. Role of the C terminus of foamy virus Gag in RNA packaging and Pol expression. J Virol. 2004;78:9423–9430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9423-9430.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cen S, Niu M, Saadatmand J, Guo F, Huang Y, Nabel GJ, Kleiman L. Incorporation of Pol into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag virus-like particles occurs independently of the upstream Gag domain in Gag-pol. J Virol. 2004;78:1042–1049. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.1042-1049.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liao WH, Huang KJ, Chang YF, Wang SM, Tseng YT, Chiang CC, Wang JJ, Wang CT. Incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase into virus-like particles. J Virol. 2007;81:5155–5165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01796-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saadatmand J, Guo F, Cen S, Niu M, Kleiman L. Interactions of reverse transcriptase sequences in Pol with Gag and LysRS in the HIV-1 tRNALys3 packaging/annealing complex. Virology. 2008;380:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dufour E, Reinbolt J, Castroviejo M, Ehresmann B, Litvak S, Tarrago-Litvak L, Andreola ML. Cross-linking localization of a HIV-1 reverse transcriptase peptide involved in the binding of primer tRNALys3. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1339–1346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arts EJ, Miller JT, Ehresmann B, Le Grice SF. Mutating a region of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase implicated in tRNALys3 binding and the consequences for (−)- strand DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14523–14532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cen S, Niu M, Kleiman L. The connection domain in reverse transcriptase facilitates the in vivo annealing of tRNALys3 to HIV-1 genomic RNA. Retrovirology. 2004;1:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pettit SC, Everitt LE, Choudhury S, Dunn BM, Kaplan AH. Initial cleavage of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 GagPol precursor by its activated protease occurs by an intramolecular mechanism. J Virol. 2004;78:8477–8485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8477-8485.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu XF, Dawson L, Tian CJ, Flexner C, Dettenhofer M. Mutations of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p6Gag domain result in reduced retention of Pol proteins during virus assembly. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:3412–3417. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3412-3417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briggs JA, Riches JD, Glass B, Bartonova V, Zanetti G, Krausslich HG. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:11090–11095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903535106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Y, Wu B, Musier-Forsyth K, Mansky LM, Mueller JD. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy on viral-like particles reveals variable gag stoichiometry. Biophys J. 2009;96:1961–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cen S, et al. Retrovirus-specific packaging of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases with cognate primer tRNAs. J Virol. 2002;76:13111–13115. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13111-13115.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levin JG, Guo J, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Nucleic Acid Chaperone Activity of HIV-1 Nucleocapsid Protein: Critical Role in Reverse Transcription and Molecular Mechanism. Progress in Nucleic Acids Research And Molecular Biology. 2005;80:217–286. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hargittai MR, Gorelick RJ, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Mechanistic insights into the kinetics of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein-facilitated tRNA annealing to the primer binding site. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:951–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang Y, Wang J, Shalom A, Li Z, Khorchid A, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. Primer tRNALys3 on the viral genome exists in unextended and two base-extended forms within mature Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:726–728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.726-728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo F, Saadatmand J, Niu M, Kleiman L. Roles of Gag and NCp7 in facilitating tRNALys3 Annealing to viral RNA in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2009;83:8099–8107. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00488-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng YX, Campbell S, Harvin D, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Rein A. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 Gag polyprotein has nucleic acid chaperone activity: possible role in dimerization of genomic RNA and placement of tRNA on the primer binding site. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:4251–4256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4251-4256.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roldan A, Warren OU, Russell RS, Liang C, Wainberg MA. A HIV-1 minimal gag protein is superior to nucleocapsid at in vitro annealing and exhibits multimerization-induced inhibition of reverse transcription. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17488–17496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cen S, Khorchid A, Gabor J, Rong L, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. The role of Pr55gag and NCp7 in tRNALys3 genomic placement and the initiation step of reverse transcription in HIV-1. J Virol. 2000;74:10796–10800. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10796-10800.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbink TE, Berkhout B. HIV-1 reverse transcription initiation: a potential target for novel antivirals? Virus Res. 2008;134:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zimmerman C, Klein KC, Kiser PK, Singh AR, Firestein BL, Riba SC, Lingappa JR. Identification of a host protein essential for assembly of immature HIV-1 capsids. Nature. 2002;415:88–92. doi: 10.1038/415088a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh CT, Sodroski J, Göttlinger HG. Functional Association of Cyclophilin A with HIV-1 Virions. Nature. 1994;372:363–365. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garrus JE, et al. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell. 2001;107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strack B, Calistri A, Craig S, Popova E, Gottlinger HG. AIP1/ALIX is a binding partner for HIV-1 p6 and EIAV p9 functioning in virus budding. Cell. 2003;114:689–699. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park SG, Schimmel P, Kim S. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and their connections to disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:11043–11049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802862105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jia J, Arif A, Ray PS, Fox PL. WHEP domains direct noncanonical function of glutamyl-Prolyl tRNA synthetase in translational control of gene expression. Mol Cell. 2008;29:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sampath P, et al. Noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase: gene-specific silencing of translation. Cell. 2004;119:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arif A, Jia J, Mukhopadhyay R, Willard B, Kinter M, Fox PL. Two-site phosphorylation of EPRS coordinates multimodal regulation of noncanonical translational control activity. Mol Cell. 2009;35:164–180. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yannay-Cohen N, et al. LysRS serves as a key signaling molecule in the immune response by regulating gene expression. Mol Cell. 2009;34:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M, Sundquist WI. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beerens N, Groot F, Berkhout B. Inititation of HIV-1 reverse transcription is regulated by a primer activation signal. JBiol Chem. 2001;276:31247–31256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]