Abstract

Actomyosin contraction directly regulates endothelial cell (EC) permeability, but intracellular redistribution of cytoskeletal tension associated with EC permeability is poorly understood. We used atomic force microscopy (AFM), EC permeability assays and fluorescence microscopy to link barrier regulation, cell remodeling and cytoskeletal mechanical properties in EC treated with barrier-protective as well as barrier-disruptive agonists. Thrombin, VEGF and H2O2 increased EC permeability, disrupted cell junctions and induced stress fiber formation. Oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (OxPAPC), HGF and iloprost tightened EC barrier, enhanced peripheral actin cytoskeleton and adherens junctions, and abolished thrombin-induced permeability and EC remodeling. AFM force mapping and imaging showed differential distribution of cell stiffness: barrier disruptive agonists increased stiffness in the central region, and barrier protective agents decreased stiffness in the center and increased it at the periphery. Attenuation of thrombin-induced permeability correlates well with stiffness changes from the cell center to periphery. These results directly link for the first time the patterns of cell stiffness with specific EC permeability responses.

Keywords: pulmonary endothelium, permeability, agonists, actin cytoskeleton, force mapping

INTRODUCTION

Vascular leak resulting from endothelial barrier compromise is a cardinal feature of acute lung injury (ALI). A complete understanding of cellular mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability is important for development of novel therapeutic strategies for treatment of this devastating condition. The lung endothelium forms a semiselective barrier between circulating blood and interstitial fluid, which is dynamically regulated by a counterbalance of barrier protective and barrier disruptive bioactive molecules present in the circulation.

Mechanisms governing vascular permeability are under intense investigation. Models of agonist-induced EC permeability consider the regulation of EC permeability as the net balance of barrier-disrupting axial contractile forces produced by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and Rho-GTPase driven actomyosin contraction, and barrier-promoting tethering/resistive forces produced by cell-cell, cell-matrix interactions, rigid cytoskeletal components (microtubules and intermediate filaments) and peripheral F-actin rim 1–5. Actomyosin contraction and its distribution in non-muscle cells have been monitored using immunofluorescent and biochemical labeling of actin remodeling, for example by monitoring the levels of phosphorylated myosin light chains. However, little is known about intracellular distribution and strength of cytoskeletal network in EC when exposed to a spectrum of barrier-active stimuli present in blood circulation.

Previous studies have used morphometric and biochemical parameters to describe agonist-induced cytoskeletal remodeling and changes in the EC contractility in response to barrier-disruptive and barrier-protective agonists. Increased permeability induced by thrombin, VEGF, hydrogen peroxide, microtubule disruptor nocodazole or other agents is associated with robust stress fiber formation and accumulation of phosphorylated regulatory myosin light chains on centrally positioned stress fibers leading to actomyosin contraction, cell retraction and disruption of EC monolayer integrity 6–10. In turn, barrier-protective agonists cause enhancement of peripheral F-actin and visible peripheral accumulation of phosphorylated regulatory myosin light chains suggesting generation of peripheral “tethering” forces 11,12. Activation of actomyosin contractility in cell cultures has been previously assessed by live microscopy of contracting single cells or cell clusters grown on ultra-thin elastic silicone membranes 13,14 or collagen lattices 15. Alternatively, traction forces generated by single cells were registered by measurements of mechanical interactions between cells and their underlying substrates by using cells seeded on microfabricated arrays of elastomeric, microneedle-like posts 16. However, these approaches are limited in their applicability to regional analysis of intracellular contractility in the cell monolayers upon treatment with barrier-protective and barrier-disruptive agonists. Atomic force microscopy provides a suitable approach for detailed analysis of nanomechanical properties of live cells 17, organnels 18 and drug-induced changes in cytoarchitecture and mechanics in cultured cells 19,20.

In this study we have used AFM to directly examine the current working model of endothelial barrier regulation as a balance between mechanical properties of contractile (centrally positioned) and tethering (distributed on the cell periphery) cytoskeletal network in endothelial permeability responses to bioactive molecules. We used two sets of agonists of different origin among which thrombin, VEGF, hydrogen peroxide exhibited barrier-disruptive effects 6,21–26, and OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost exhibit barrier-protective effects 6,21,27–32. We measured patterns of agonist-induced changes in local elastic modulus and linked them with immunofluorescence analysis of cytoskeletal remodeling and measurements of EC permeability responses. Finally, barrier-protective effects of OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost on thrombin-induced EC barrier dysfunction were linked to stiffness redistribution from central to peripheral cellular compartments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cell culture

Primary antibodies to VE-cadherin were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA). Texas Red phalloidin and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased form Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). VEGF and HGF were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), thrombin, iloprost were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (OxPAPC) was obtained by exposure of dry lipid to air as previously described 27,28,33. The extent of oxidation was measured by positive ion electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) described elsewhere 33. Next, oxidized lipids dissolved in chloroform were stored at −70oC and used within 2 weeks after mass spectrometry testing. All oxidized and non-oxidized phospholipid preparations were analyzed by the limulus amebocyte assay (BioWhittaker, Frederick, MD) and shown negative for endotoxin. Unless specified, all other biochemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) were obtained from Lonza Inc (Allendale, NJ), cultured according to manufacturer’s protocol, and used at passages 5–9.

Measurement of transendothelial electrical resistance

The cellular barrier properties were analyzed by measurements of transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) across confluent human pulmonary artery endothelial monolayers using an electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY). TER values from at least six microelectrodes corresponding to each experimental condition were pooled at discrete time points using custom designed Epool software and plotted vs. time as the mean ± SD as previously described 28,34.

Immunofluorescent staining

Endothelial cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed after agonist treatment in 3.7% formaldehyde solution in PBS for 10 min at 4oC, washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Tween-20 and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature, and blocked with 2% BSA in PBST for 30 min. Incubation with VE-cadherin antibodies was performed in PBS containing 0.2% Tween-20 and 2% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature followed by staining with Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Actin filaments were stained with Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes) for 1 hr at room temperature. After immunostaining, the glass slides were analyzed using Nikon video-imaging system (Nikon Instech Co., Japan) consisting of a inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse TE300 with epi-fluorescence module using 60XA/1.40 oil objective connected to SPOT RT monochrome digital camera and image processor (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). The images were recorded and processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) software.

In vitro endothelial permeability assay

Similar to the measurements of transendothelial albumin clearance 21, permeability to FITC-labeled dextran was assessed across HPAEC monolayers grown on transwell inserts using an In Vitro Vascular Permeability Assay Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to manufacturer’s protocol, as we have previously described 31.

Atomic force microscopy

Imaging was carried out with a Bioscope AFM (a prototype of Digital Instruments Bioscope) integrated with a Zeiss Axiovert 135TV inverted light microscope 35,36, using version 5,12R3 of the NanoScope software. For some experiments, a 150 × 150 μm2 “J” scanner from a Nanoscope III Extended Multimode AFM from Veeco (Santa Barbara, CA) was also used. Imaging of fixed cells in air and PBS buffer was performed in contact mode. Cantilevers with nominal spring constants of k=0.06 N/m purchased from Veeco (Santa Barbara, CA) were utilized for imaging and elasticity measurements. A nominal radius of 30 nm was used for the tip radius. The same cantilever was used to compare mechanical properties of all cells. Mechanical properties were measured by acquiring point-by-point force vs. distance curves over 32×32 arrays (force-volume). The tip velocities for these measurements varied between 1 μm/s and 3 μm/s. The sensitivity of the photodetector was calibrated by acquiring force vs. distance curves on a clean glass substrate.

A home written MatLab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) code was used to obtain elasticity maps from force volume data 37. A line of zero force was defined from the average deflection of points in the force curve corresponding to the positions of the cantilever when it is far away from the surface. The origin of the indentation curve was chosen as the point where the retraction curve intersected the line of zero force. The cell’s vertical deformation (penetration depth of the tip) was obtained by subtracting the cantilever deflection from the displacement of the piezo element. These values were plotted along the x-axis of the indentation curve. Indentation forces were calculated by multiplying the elastic constant of the cantilever by the cantilever deflection. To check the consistency of these results, a manual inspection of the force curves was performed and, when necessary, the data was reanalyzed until the computed results and manual examinations agreed reasonably. A value of zero was assigned to the elastic modulus in regions where cells’ features were either absent or too thin, and these were consequently excluded from further analysis. The same procedure was followed for data points that exceeded maximum typical values (1 MPa), regardless of the specimen’s thickness in the region.

The cell’s periphery and nucleus were defined from AFM height images acquired in contact mode. Data points inside a region of the map could be selected for further analysis by choosing the start and end points of polygonal lines. If only two points were selected, the program delivered a cross section of the selected line. Indentation curves were fitted according to the Hertz model, from which the values of elastic modulus plotted in the maps were obtained. The ratio of elastic moduli at the cell’s periphery (Ep) and cell’s center (En) was obtained from cross sections traced along the elasticity map of a cell. Importantly, unknown exact values of the cantilever’s spring constant and tip radius are not expected to contribute significantly to the error in the Ep/En ratio.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± SD of three to ten independent experiments. Experimental samples were compared to controls by unpaired Student’s t-test. For multiple-group comparisons, a one-way variance analysis (ANOVA), followed by the post hoc Fisher’s test, were used. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Changes in pulmonary endothelial permeability induced by thrombin, VEGF, hydrogen peroxide, OxPAPC, HGF, and iloprost

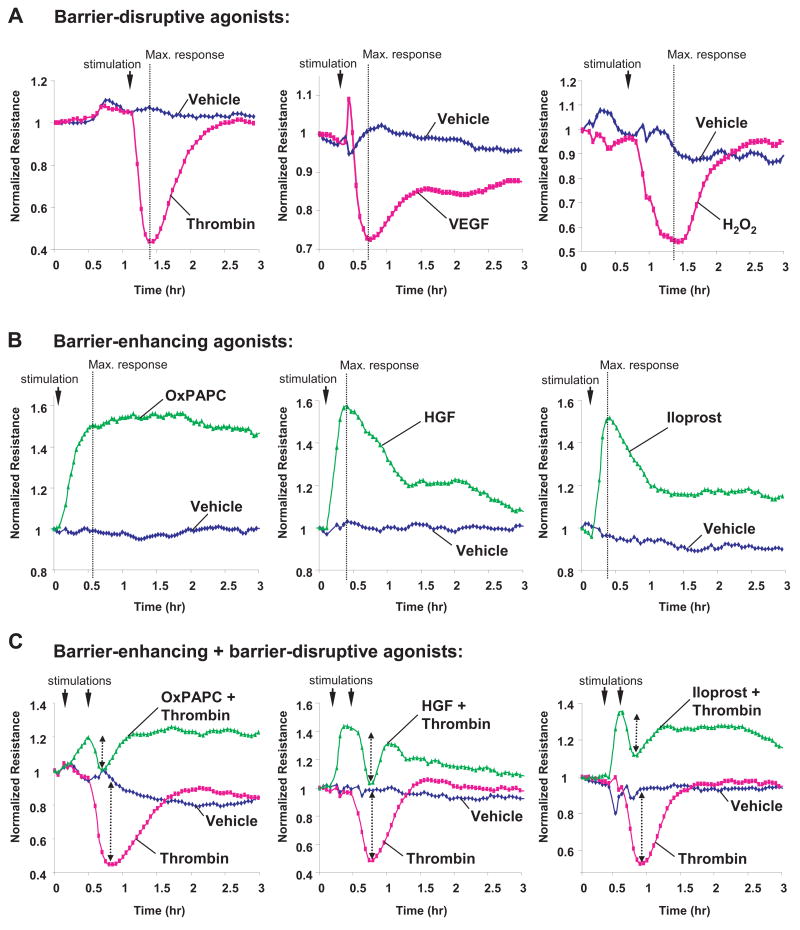

Human pulmonary EC monolayers were treated with thrombin, VEGF, hydrogen peroxide, OxPAPC, HGF, and iloprost followed by measurements of TER for 3 hrs in parallel experiments. Treatment with thrombin, VEGF and hydrogen peroxide significantly increased EC monolayer permeability 6,24,38,39 that reached maximum at different time points, as monitored by decline in TER (Figure 1A). EC stimulation with OxPAPC, HGF and prostacyclin analog iloprost increased TER, although in different fashion (Figure 1B). Consistent with previous findings 27,30,32,40, pretreatment with barrier-protective agents OxPAPC, HGF or iloprost significantly attenuated absolute values of thrombin-induced TER decline. This finding reflects EC barrier compromise and also reduced relative TER changes in response to thrombin in EC pretreated with barrier-protective agonists (Figure 1C, shown by arrows). TER measurements show that OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost also attenuated EC barrier dysfunction induced by hydrogen peroxide and VEGF (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Effect of thrombin, VEGF, hydrogen peroxide, OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost on transendothelial electrical resistance.

HPAEC monolayers were grown on gold microelectrodes. At the time point indicated by arrow, cells were treated with: A - 0.2 U/ml thrombin, 200 ng/ml VEGF, 100 μM H202; B - 20 μg/ml, OxPAPC, 20 ng/ml HGF, 200 ng/ml iloprost; or C - pretreated with OxPAPC, HGF or iloprost prior to thrombin stimulation, and transendothelial resistance was monitored during 3 hrs. Results are representative of five independent experiments.

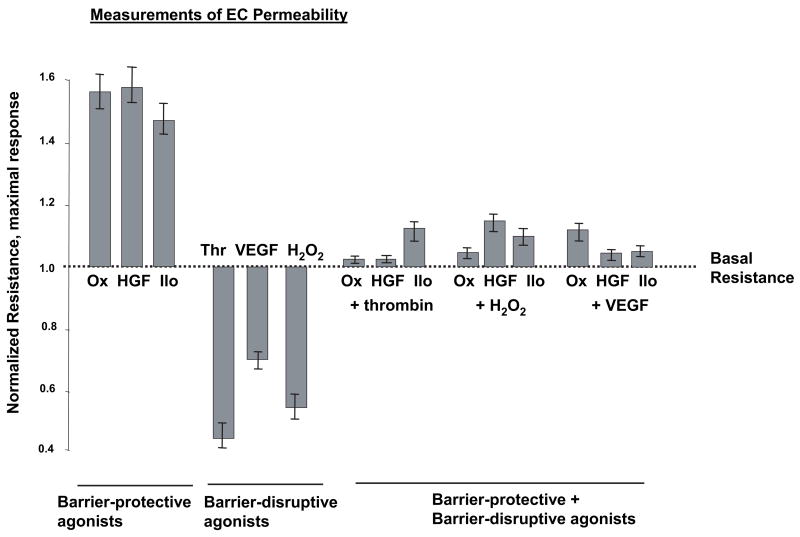

Figure 2. Summary of agonist effects on EC permeability.

TER measurements were made at the time points corresponding to maximal TER changes in response to each agonist shown by vertical lines in Figure 1. Shown are pooled data of three to eight independent experiments.

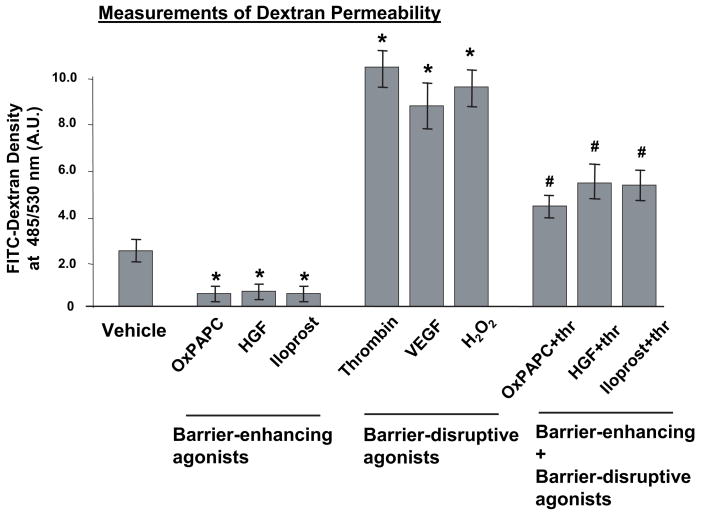

Agonist-induced permeability changes in human pulmonary EC monolayers were also analyzed by the solute flux assay 31. EC monolayers grown on semi-permeable membranes were pretreated with barrier-protective or barrier-disruptive agonists alone or with OxPAPC, HGF or iloprost followed by thrombin challenge, and permeability for FITC-labeled dextran was assessed in transwell assays. Similar to effects on TER, OxPAPC, HGF, and iloprost markedly reduced basal EC monolayer permeability and significantly attenuated thrombin-induced permeability for FITC-labeled dextran (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of agonists on endothelial monolayer permeability for micromolecules.

HPAEC monolayers grown in transwell plates were treated with 20 μg/ml, OxPAPC, 20 ng/ml HGF, 200 ng/ml iloprost, 0.2 U/ml thrombin, 200 ng/ml VEGF, 100 μM H202 for 2 hrs, or cells pretreated with OxPAPC, HGF or iloprost (15 min) were further challenged with thrombin (2 hrs). Measurements of permeability for FITC-labeled dextran were performed as outlined in Methods section. Shown are pooled data of three independent experiments. Results are represented as mean ± SD. *p<0.01, versus vehicle control; #p<0.01, versus stimulation with barrier disruptive agonists alone.

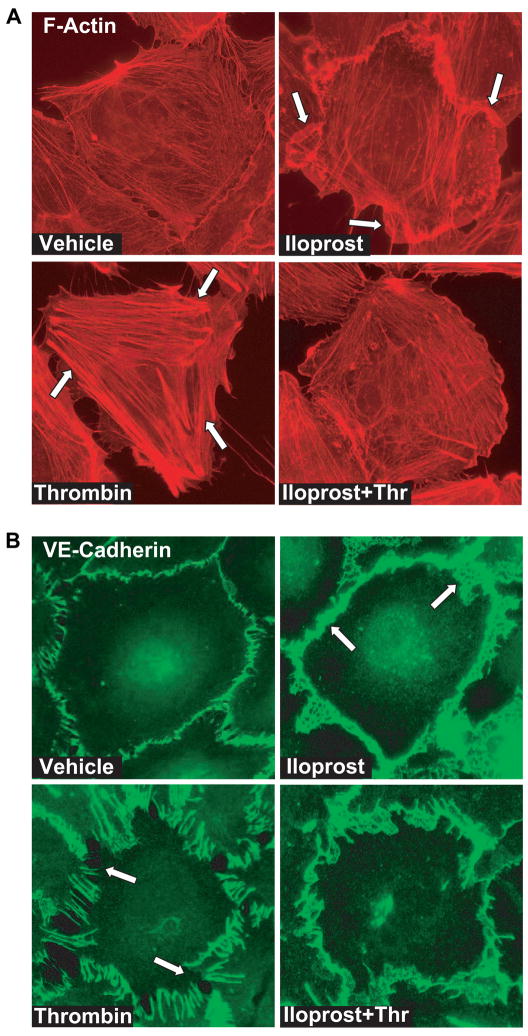

Agonist-induced remodeling of actin cytoskeleton and adherens junctions

In order to link agonist-induced EC permeability with morphological changes, we analyzed redistribution of actin cytoskeleton and adherens junctions by imaging of agonist-stimulated EC monolayers subjected to immunofluorescent staining with Texas Red phalloidin and antibodies to VE-cadherin. Thrombin and iloprost were chosen as representative barrier-disruptive and barrier-protective agonist, respectively. Consistent with previous observations, thrombin caused robust stress fiber formation (Figure 4A) and disruption of continuous pattern of VE-cadherin peripheral staining (Figure 4B). In contrast, iloprost induced accumulation of F-actin at the cell periphery (Figure 4A, shown by arrows) and enhancement of continuous VE-cadherin-positive peripheral staining of EC in monolayer (Figure 4B). Significantly, inhibition of thrombin-induced permeability by iloprost (Figures 1, 2) was associated with marked attenuation of thrombin-induced stress fiber formation and partial preservation of peripheral F-actin structure in the iloprost-pretreated EC (Figure 4A) that partially preserved the continuity of adherens junctions (Figure 4B). We also linked actin cytoskeletal redistribution induced by barrier-protective and barrier-disruptive agents with changes in local elasticity.

Figure 4. Effect of OxPAPS on thrombin-induced cytoskeletal remodeling and adherens junction integrity.

EC grown on glass coverslips were incubated with iloprost (200 ng/ml, 15 min) or thrombin (0.2 U/ml, 15 min) alone or with iloprost followed by thrombin treatment for 15 min. Cells were fixed, and double immunofluorescent staining was performed according to the protocol described in the Methods section. Cells were probed with Texas Red phalloidin to detect actin filaments (A) and with VE-cadherin antibody to label adherens junctions (B). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Force mapping of agonist-stimulated human pulmonary endothelial cells

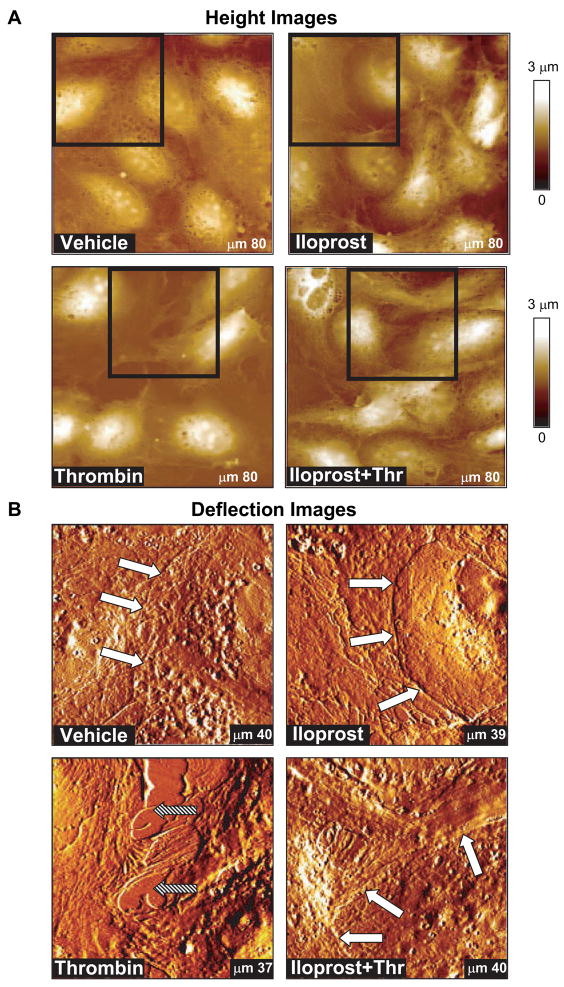

The cell periphery and nucleus in the elasticity map were defined from AFM height images of control and agonist-stimulated cells acquired in contact mode (Figure 5A). Large scale AFM deflection images of EC monolayers as well as imaging and elasticity measurements of single cells within EC monolayers provided high resolution details of cell morphology and allowed analysis of cell shape changes in control and agonist-stimulated EC. AFM images are consistent with the images obtained using conventional optical microscopy. High resolution AFM images of EC cytoskeleton in the iloprost-stimulated EC show increased peripheral cytoskeletal redistribution (Figure 5B, white arrows). In contrast, thrombin stimulation caused assembly of cytoskeletal fibers in the central part of the cell and created intercellular gaps with areas of up to tens of μm2 in thrombin-stimulated EC (Figure 5B, filled arrows). Pretreatment with iloprost attenuated gap formation caused by thrombin and restored peripheral cytoskeletal structure (Figure 5B, lower panels). Gap areas decreased in this case to only a few μm2. These data are highly consistent with changes in actin cytoskeletal arrangement monitored by immunofluorescent staining of agonist-stimulated EC monolayers (Figure 4).

Figure 5. Height and deflection images of agonist-stimulated pulmonary endothelial cell monolayers.

Pulmonary EC grown on glass coverslips and treated with iloprost (200 ng/ml, 15 min), thrombin (0.2 U/ml, 15 min), or combination of iloprost and thrombin, as described in previous figures, were used for image acquisition using AFM techniques. A - AFM height images of larger areas of EC monolayers; B - deflection images showing more detail of the regions indicated with squares in panel A. Data were acquired using the same cantilever with 0.06 N/m spring constant in PBS buffer at room temperature, as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are representative data of three independent experiments.

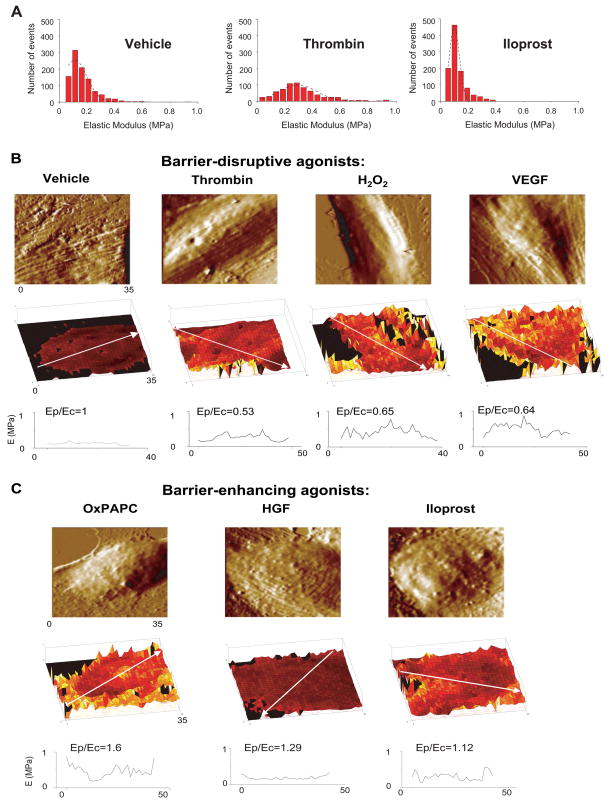

In agreement with previous works, elasticity maps in our study revealed elastic moduli in the order of 0.1–1 MPa (Figure 6A) 41,42. For the maximum loads used in our measurements (typically ~ 5 nN), the cells deformation as a result of the pressure applied by the AFM tip was ~ 200 nm. Since this depth corresponds primarily to the cytoskeletal region, and the plasma membrane stiffness is negligible in comparison to the stiffness of the underlying actomyosin cytoskeleton, these measurements depict regional changes in cytoskeletal stiffness induced by barrier-protective and barrier-disruptive agonists. We further depicted the distribution of elastic modulus in control and agonist-stimulated cells as a histogram (Figure 6A). Although the maximum of the elastic modulus distribution was ~ 0.1 MPa for both vehicle- and iloprost-treated cells, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) was significantly decreased in the iloprost-treated cells (FWHM values of 0.2 MPa for vehicle and 0.1 MPa for iloprost-treated cells respectively). These results suggest certain decrease in the basal cellular stiffness as result of iloprost treatment. Thrombin challenge increased the maximum of the elastic modulus distribution to ~ 0.25 MPa. In addition, thrombin -treated cells displayed a wider (FWHM value of 0.3 MPa) distribution of elastic modulus than vehicle cells. The results shown in Figure 6 are highly consistent with thrombin-induced generalized endothelial contraction leading to disruption of EC monolayer integrity, and iloprost-mediated relaxation of central cytoskeletal compartment with still preserved or even enhanced peripheral stiffness, which is associated with increased EC barrier properties. More detailed analysis of regional stiffness distribution was performed in the next experiments.

Figure 6. Effects of barrier-disruptive and barrier-protective agonists on intracellular elasticity distribution measured using atomic force microscopy.

A - Human pulmonary endothelial cell monolayers grown on glass coverslips and treated for 15 min with vehicle (left panels), 0.2 U/ml thrombin (middle panels), or 200 ng/ml iloprost were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and used for elasticity measurements by AFM. Histograms represent the overall distribution of elastic modulus across the entire cell. A Gaussian fit (black dashed line) is superimposed on each histogram. Full widths at half maximum (FWHM) values of the distributions are 0.2 MPa (vehicle), 0.3 MPa (thrombin) and 0.1 MPa (iloprost). Human pulmonary endothelial cell monolayers grown on glass coverslips and treated for 15 min with: B - 0.2 U/ml thrombin, 200 ng/ml VEGF, 100 μM H202, or C - 20 μg/ml, OxPAPC, 20 ng/ml HGF or 200 ng/ml iloprost were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and used for elasticity measurements by AFM. Shown are representative samples of multiple analyzed cells and measurements. Scale in z-axis (elastic modulus): 0–1 MPa for all elasticity maps. Scale is color coded in tones of black, red, yellow and white, with black corresponding to 0 MPa and white to 1 MPa. Directions of elasticity scans used for calculations of Ep/Ec ratios are shown by arrows.

The analysis of the overall elastic modulus as a result of agonist action is complicated by several effects, including cell fixation and the AFM technique itself 36,41,43. On the other hand, experiments with live cells are complicated by relatively low cell-substrate adhesive forces and the rapid action of agonists in timescales difficult to follow with the AFM. Therefore, for these preliminary experiments, relative variations in the elastic modulus of the peripheral cytoplasm to the elastic modulus in the cell nucleus (Ep/Ec values) were studied. Differences in the Ep/Ec ratio were small, but still discernable. The elastic moduli measured in our experiments are directly associated with subcellular mechanical properties 36, In addition, they provide an indirect connection to intracellular forces via relationships between the elastic modulus, bulk modulus and Gibbs free energy 44. While these relationships have been examined in detail for ionic crystals 45, they are discussed here only qualitatively. Generally, larger cohesion forces in the cytoskeleton are expected to be reflected by larger values of elastic moduli.

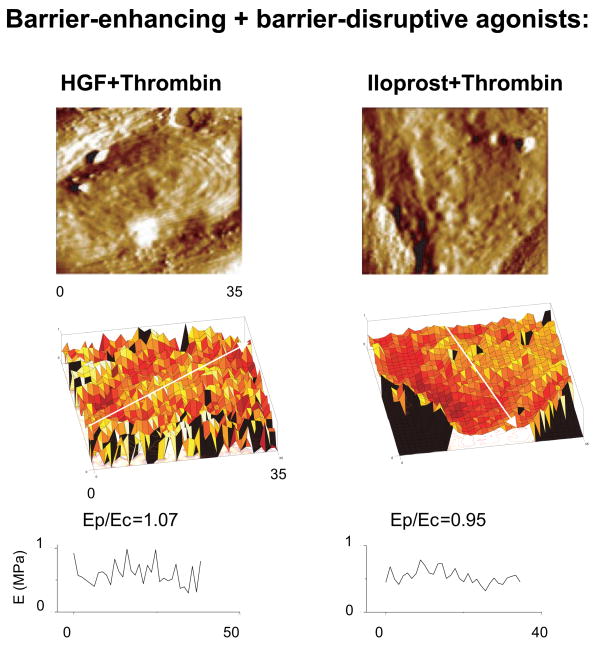

Elasticity maps of agonist-stimulated EC monolayers suggest that barrier-disruptive agonists thrombin, H202 and VEGF increased elastic modulus in the central part of the cell (Ec) as compared to the cell periphery (Ep) (Figure 6B). Calculated Ep/Ec ratios were typically less than one (within 0.53 – 0.65 range) for characteristic directions along the cells that correlated with the redistribution of actin in fluorescence images. In comparison to barrier-disruptive agents, agonists with barrier protective properties (OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost) decreased overall stiffness (mean value across the entire cell, Figure 6), but preserved or even increased the elastic modulus at the cell periphery with respect to the central part of the cell resulting to the increased Ep/Ec ratios (Figure 6C). Due to inherent differences in the elastic modulus distribution in different cells, selection of the direction for regional stiffness scanning in each cell may cause fluctuations of Ep/Ec values. However, even with these variations, EC stimulated with all three barrier protective agents (OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost) showed higher Ep/Ec ratios with respect to control cells and EC stimulated with barrier-disruptive agonists. These results are highly consistent with the model of the maintenance of EC barrier properties via increased tethering forces generated during enhancement of peripheral actomyosin cytoskeleton and cell-cell junctions 3. Significantly, cell pretreatment with barrier-protective agonists HGF and iloprost, which attenuate thrombin-induced EC barrier dysfunction, reversed the intracellular distribution of elastic modulus and increased Ep/Ec ratios to 0.95 –1.07 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Measurements of intracellular elasticity distribution in agonist-stimulated EC using atomic force microscopy.

Human pulmonary endothelial cell monolayers grown on glass coverslips and pretreated with HGF or iloprost (15 min) prior to thrombin challenge (15 min) were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and used for elasticity measurements by AFM. Shown are representative samples of multiple measurements. Scale in z-axis (elastic modulus): 0–1 MPa for both elasticity maps. Scale is color coded in tones of black, red, yellow and white, with black corresponding to 0 MPa and white to 1 MPa.

DISCUSSION

Here we described specific patterns of local intracellular elasticity in human pulmonary EC monolayers and linked them with actin cytoskeletal remodeling, rearrangement of cell-cell adherens junctions, and barrier response to agonist stimulation. These results support the model of EC barrier regulation as a balance between central contractile and circumferential tethering forces imposed by actomyosin cytoskeleton. In addition, our studies show that protective effects of OxPAPC, HGF and iloprost against EC hyper-permeability induced by barrier-disruptive agents of different origin are associated with redistribution of intracellular elastic modulus. Protective agonists caused increases in peripheral and decreases in central contractility reflected by changes in the Ep/Ec ratios. It is also important to note that dramatic redistribution of VE-cadherin to the cell junctions caused by iloprost and other barrier protective agonists and resulting increases in cell-cell adhesiveness may serve as complementary mechanism enhancing endothelial monolayer barrier properties without affecting cellular elastic modulus.

Previous studies utilized biochemical and morphological markers, such as MLC phosphorylation, protein translocation from cytosolic to membrane/cytoskeletal fractions, electron microscopy analysis of EC gaps, actin remodeling, morphological enlargement or disassembly of cell adhesion complexes upon agonist stimulation to characterize endothelial permeability (see for 2,4 review). These approaches only indirectly implied a role of contractile forces in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Functional assays such as membrane wrinkling assay, collagen lattices or single cell traction force analysis were used to confirm activation of EC contraction by edemagenic agonists (thrombin, nocodazole) leading to EC hyperpermeability 13–16. However, without AFM studies, it was very difficult if not impossible to a) quantitatively analyze stiffness/elastic modulus in a particular EC contained within endothelial monolayer; b) determine the distribution of subcellular mechanical indices; c) compare effects of barrier-protective and barrier-disruptive agonists on intracellular mechanical properties; and d) link these data with morphological and functional changes in EC monolayers. Increasing number of studies refers to cortical actin cytoskeletal enhancement as a major mechanism of EC barrier protection. However, mechanical properties of EC peripheral cytoskeleton have not been directly tested. We believe that changes in mechanical properties of cortical cytoskeleton and cell-cell adhesive complexes are keys to understanding the molecular mechanisms of agonist-induced EC barrier enhancement and barrier recovery. These measurements are only possible by using AFM methods including those described in this study. Ongoing studies by our group will further characterize cytoskeletal and cell adhesion protein targets involved in dynamic changes in cortical cytoskeletal mechanics critical for EC barrier protection and recovery.

The barrier-disruptive agonists used in this study trigger various signaling molecules including myosin light chain kinase, Rho-GTPase, protein kinase C, Erk-1,2, p38 MAP kinases, NFκB, which may cause EC barrier compromise 6,7,46–51. Similarly, agonist-induced barrier-protective effects are also mediated by various signaling pathways including Rac and Cdc42 GTPases, protein kinase A, Epac-Rap1 signaling, PI3-kinase, etc. 29–31,40,52,53. However, the common feature of EC responses to various barrier-disruptive agonists is formation of centrally positioned actomyosin filaments leading to cell retraction, disruption of cell-cell contacts and EC monolayer integrity. In turn, barrier-protective agonists OxPAPC, HGF and prostacyclin analog iloprost tested in this study, although associated with activation of distinct signaling pathways, however enhanced peripheral cytoskeleton and peripheral elasticity modulus.

The mechanisms of differential actin cytoskeletal remodeling induced by barrier-protective and barrier-disruptive agents are not yet fully understood. Increasing number of publications including our studies 11,27,54,55 suggest a central role for Rac GTPase in the peripheral actin cytoskeletal remodeling and cell-cell junction assembly. Indeed, Rac activation has been reported in EC stimulated with OxPAPC, HGF and prostacyclin 27,29–31,56. In contrast, activation of Rho GTPase and myosin light chain kinase, which promote central stress fiber formation, cell retraction and disruption of cell-cell contacts has been described in EC challenged with thrombin, H2O2 and VEGF 6,7,9,48.

In summary, this study provides comprehensive analysis of cytoskeletal remodeling examined in parallel by immunofluorescent staining and AFM methods and links differential patterns of force distribution in EC monolayers with specific permeability responses. Results of AFM analysis of regional cytoskeletal stiffness in the agonist-stimulated EC monolayers support the model of endothelial barrier regulation via a balance between centrally localized contractile and peripheral tethering forces. The AFM approach described in this study provides a suitable assay to test the role of specific molecules in EC contractility and barrier regulation via force mapping of the individual cells expressing functional mutants of signaling or cytoskeletal proteins within intact EC monolayers. Furthermore, parallel force mapping of macro- and microvascular EC monolayers may help identify the differences in the patterns of cytoskeletal remodeling, tethering forces and cell-cell adhesive forces observed in the lung macro- and microvascular beds and associated with regional differences in regulation of lung permeability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes grants HL076259, HL075349, and HL58064, the American Lung Association Career Investigator Grant (KGB); National Scientist Developing Grant from the American Heart Association (AAB), the American Lung Association Biomedical Research Grant (AAB); and Department of Medicine Developmental Fund (RL, FTA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lum H, Malik AB. Mechanisms of increased endothelial permeability. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:787–800. doi: 10.1139/y96-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1487–500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:575–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan SY. Protein kinase signaling in the modulation of microvascular permeability. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39:213–23. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birukova AA, Smurova K, Birukov KG, Kaibuchi K, Garcia JGN, Verin AD. Role of Rho GTPases in thrombin-induced lung vascular endothelial cells barrier dysfunction. Microvasc Res. 2004;67:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Davis HW. Hydrogen peroxide-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement in cultured pulmonary endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1998;174:370–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199803)174:3<370::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Deciphering vascular endothelial cell growth factor/vascular permeability factor signaling to vascular permeability. Inhibition by atrial natriuretic peptide. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44385–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun H, Breslin JW, Zhu J, Yuan SY, Wu MH. Rho and ROCK signaling in VEGF-induced microvascular endothelial hyperpermeability. Microcirculation. 2006;13:237–47. doi: 10.1080/10739680600556944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birukova AA, Smurova K, Birukov KG, Usatyuk P, Liu F, Kaibuchi K, et al. Microtubule disassembly induces cytoskeletal remodeling and lung vascular barrier dysfunction: Role of Rho-dependent mechanisms. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201:55–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:689–701. doi: 10.1172/JCI12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birukov KG, Birukova AA, Dudek SM, Verin AD, Crow MT, Zhan X, et al. Shear stress-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling and cortactin translocation in pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:453–64. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogatcheva NV, Verin AD, Wang P, Birukova AA, Birukov KG, Mirzopoyazova T, et al. Phorbol esters increase MLC phosphorylation and actin remodeling in bovine lung endothelium without increased contraction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L415–26. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00364.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verin AD, Birukova A, Wang P, Liu F, Becker P, Birukov K, et al. Microtubule disassembly increases endothelial cell barrier dysfunction: role of MLC phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L565–74. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byfield FJ, Tikku S, Rothblat GH, Gooch KJ, Levitan I. OxLDL increases endothelial stiffness, force generation, and network formation. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:715–23. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500439-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan JL, Tien J, Pirone DM, Gray DS, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cells lying on a bed of microneedles: an approach to isolate mechanical force. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1484–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235407100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelling AE, Sehati S, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, Gimzewski JK. Local nanomechanical motion of the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2004;305:1147–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1097640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riethmuller C, Schaffer TE, Kienberger F, Stracke W, Oberleithner H. Vacuolar structures can be identified by AFM elasticity mapping. Ultramicroscopy. 2007;107:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesen D, Hoh JH. Micromechanical architecture of the endothelial cell cortex. Biophys J. 2005;88:670–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotsch C, Radmacher M. Drug-induced changes of cytoskeletal structure and mechanics in fibroblasts: an atomic force microscopy study. Biophys J. 2000;78:520–35. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76614-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia JG, Siflinger-Birnboim A, Bizios R, Del Vecchio PJ, Fenton JW, 2nd, Malik AB. Thrombin-induced increase in albumin permeability across the endothelium. J Cell Physiol. 1986;128:96–104. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslin JW, Pappas PJ, Cerveira JJ, Hobson RW, 2nd, Duran WN. VEGF increases endothelial permeability by separate signaling pathways involving ERK-1/2 and nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H92–H100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00330.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niwa K, Inanami O, Ohta T, Ito S, Karino T, Kuwabara M. p38 MAPK and Ca2+ contribute to hydrogen peroxide-induced increase of permeability in vascular endothelial cells but ERK does not. Free Radic Res. 2001;35:519–27. doi: 10.1080/10715760100301531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usatyuk PV, Vepa S, Watkins T, He D, Parinandi NL, Natarajan V. Redox regulation of reactive oxygen species-induced p38 MAP kinase activation and barrier dysfunction in lung microvascular endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:723–30. doi: 10.1089/152308603770380025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Issbrucker K, Marti HH, Hippenstiel S, Springmann G, Voswinckel R, Gaumann A, et al. p38 MAP kinase--a molecular switch between VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular hyperpermeability. Faseb J. 2003;17:262–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0329fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavard J, Gutkind JS. VEGF controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the beta-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1223–34. doi: 10.1038/ncb1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birukov KG, Bochkov VN, Birukova AA, Kawkitinarong K, Rios A, Leitner A, et al. Epoxycyclopentenone-containing oxidized phospholipids restore endothelial barrier function via Cdc42 and Rac. Circ Res. 2004;95:892–901. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147310.18962.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birukova AA, Fu P, Chatchavalvanich S, Burdette D, Oskolkova O, Bochkov VN, et al. Polar head groups are important for barrier protective effects of oxidized phospholipids on pulmonary endothelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L924–35. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00395.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birukova AA, Alekseeva E, Mikaelyan A, Birukov KG. HGF attenuates thrombin-induced permeability in the human pulmonary endothelial cells by Tiam1-mediated activation of the Rac pathway and by Tiam1/Rac-dependent inhibition of the Rho pathway. FASEB J. 2007;21:2776–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7660com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu F, Schaphorst KL, Verin AD, Jacobs K, Birukova A, Day RM et al. Hepatocyte growth factor enhances endothelial cell barrier function and cortical cytoskeletal rearrangement: potential role of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. FASEB J. 2002;16:950–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0870com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Alekseeva E, Fu P, Chen W, Jacobson JR, et al. Prostaglandins PGE2 and PGI2 promote endothelial barrier enhancement via PKA- and Epac1/Rap1-dependent Rac activation. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2504–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farmer PJ, Bernier SG, Lepage A, Guillemette G, Regoli D, Sirois P. Permeability of endothelial monolayers to albumin is increased by bradykinin and inhibited by prostaglandins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L732–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson AD, Leitinger N, Navab M, Faull KF, Horkko S, Witztum JL, et al. Structural identification by mass spectrometry of oxidized phospholipids in minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein that induce monocyte/endothelial interactions and evidence for their presence in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13597–607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nonas SA, Miller I, Kawkitinarong K, Chatchavalvanich S, Gorshkova I, Bochkov VN, et al. Oxidized phospholipids reduce vascular leak and inflammation in rat model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1130–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1737OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quist AP, Rhee SK, Lin H, Lal R. Physiological role of gap-junctional hemichannels. Extracellular calcium-dependent isosmotic volume regulation. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1063–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almqvist N, Bhatia R, Primbs G, Desai N, Banerjee S, Lal R. Elasticity and adhesion force mapping reveals real-time clustering of growth factor receptors and associated changes in local cellular rheological properties. Biophys J. 2004;86:1753–62. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arce FT, Avci R, Beech IB, Cooksey KE, Wigglesworth-Cooksey B. Modification of surface properties of a poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based elastomer, RTV11, upon exposure to seawater. Langmuir. 2006;22:7217–25. doi: 10.1021/la060809a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:510–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker PM, Verin AD, Booth MA, Liu F, Birukova A, Garcia JG. Differential regulation of diverse physiological responses to VEGF in pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1500–11. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.6.L1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birukova AA, Malyukova I, Mikaelyan A, Fu P, Birukov KG. Tiam1 and betaPIX mediate Rac-dependent endothelial barrier protective response to oxidized phospholipids. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:608–17. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terán Arce F, Whitlock JL, Birukova AA, Birukov KG, Arnsdorf MF, Lal R, et al. Regulation of the micromechanical properties of pulmonary endothelium by S1P and thrombin: role of cortactin. Biophys J. 2008 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127167. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutter JL, Chen J, Wan WK, Uniyal S, Leabu M, Chan BM. Atomic force microscopy investigation of the dependence of cellular elastic moduli on glutaraldehyde fixation. J Microsc. 2005;219:61–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2005.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moloney M, McDonnell L, O’Shea H. Atomic force microscopy of BHK-21 cells: an investigation of cell fixation techniques. Ultramicroscopy. 2004;100:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landau LD, Lifschitz EM. Theory of elasticity. Oxford Pergammon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fraxedas J, Garcia-Manyes S, Gorostiza P, Sanz F. Nanoindentation: Toward the sensing of atomic interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5228–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042106699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huot J, Houle F, Rousseau S, Deschesnes RG, Shah GM, Landry J. SAPK2/p38-dependent F-actin reorganization regulates early membrane blebbing during stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1361–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rousseau S, Houle F, Landry J, Huot J. p38 MAP kinase activation by vascular endothelial growth factor mediates actin reorganization and cell migration in human endothelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;15:2169–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, Versteilen A, van Hinsbergh VW. Involvement of RhoA/Rho kinase signaling in VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:211–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054198.68894.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kevil CG, Oshima T, Alexander JS. The role of p38 MAP kinase in hydrogen peroxide mediated endothelial solute permeability. Endothelium. 2001;8:107–16. doi: 10.3109/10623320109165320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowie A, O’Neill LA. Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappaB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tolando R, Jovanovic A, Brigelius-Flohe R, Ursini F, Maiorino M. Reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokine signaling in endothelial cells: effect of selenium supplementation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:979–86. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birukova AA, Chatchavalvanich S, Oskolkova O, Bochkov VN, Birukov KG. Signaling pathways involved in OxPAPC-induced pulmonary endothelial barrier protection. Microvasc Res. 2007;73:173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singleton PA, Dudek SM, Chiang ET, Garcia JG. Regulation of sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced endothelial cytoskeletal rearrangement and barrier enhancement by S1P1 receptor, PI3 kinase, Tiam1/Rac1, and alpha-actinin. Faseb J. 2005;19:1646–56. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3928com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dudek SM, Jacobson JR, Chiang ET, Birukov KG, Wang P, Zhan X, et al. Pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement by sphingosine 1-phosphate: roles for cortactin and myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24692–700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Birukova AA, Malyukova I, Poroyko V, Birukov KG. Paxillin - {beta}-catenin interactions are involved in Rac/Cdc42-mediated endothelial barrier-protective response to oxidized phospholipids. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L199–211. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00020.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuhara S, Sakurai A, Sano H, Yamagishi A, Somekawa S, Takakura N, et al. Cyclic AMP potentiates vascular endothelial cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact to enhance endothelial barrier function through an Epac-Rap1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:136–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.136-146.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]