Abstract

This is a case report of a 61-year-old cardiac transplant patient who developed a disseminated infection involving the upper extremity with a rare fungus known as Aspergillus ustus. The patient was successfully treated with aggressive serial debridements, antifungal medications, and reduction of immunosuppression. With these interventions, the patient avoided amputation despite the aggressive nature of this infection.

Keywords: Aspergillus ustus, Aspergillosis, Fungal hand infection, Case report

Introduction

This is a case report of a 61-year-old cardiac transplant patient who developed an invasive hand infection involving a form of Aspergillus known as Aspergillus ustus. Such infections are extremely rare representing less than 1% of all infections with Aspergillus worldwide. Since 1970, less than 30 cases of disseminated A. ustus infections have been reported. We report the second case of primary cutaneous aspergillosis caused by A. ustus.

Case Report

A 61-year-old man with a history of dilated cardiomyopathy underwent cardiac transplantation and was placed on cyclosporine and mycophenolate. Three months after discharge, he presented with complaints of persistent cough and left arm pain. A chest computed tomography scan, performed to evaluate the patient’s respiratory complaints, revealed small nodular opacities in his lungs bilaterally. Cultures and stains from bronchiolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy were unrevealing but the patient was found to have a high level of serum galactomannan, a component of the fungal cell wall in various species of Aspergillus. He was therefore empirically treated with voriconazole and caspofungin for suspected pulmonary aspergillosis.

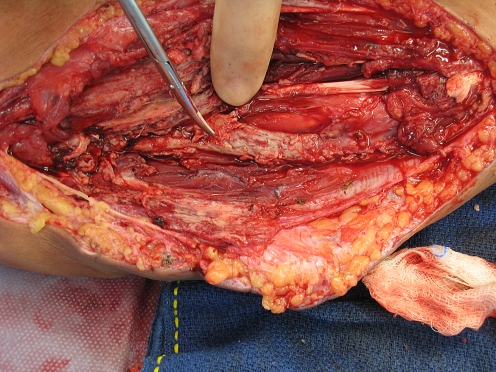

He also complained of pain in his left arm and was noted to have slight swelling over the volar aspect of his left forearm. He denied fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms. A punch biopsy of the skin was taken and the patient was started on empiric treatment for bacterial cellulitis. He slightly improved but 12 days later described increased forearm pain with new onset of paresthesias in the ulnar distribution and difficulty flexing his fingers. Guided aspiration was ordered, which yielded approximately 3 ml of purulent fluid from a well-circumscribed primarily solid mass measuring about 4 × 5 cm. That patient was immediately taken to the operating room for exploration. Upon opening the volar forearm, we found a purulent pocket with involvement of both superficial and deep flexor compartments of the forearm. The flexor digitorum superficialis muscles were necrotic (Fig. 1) and were excised. There was a thick white rind adherent to the ulnar neurovascular bundle (Fig. 2). The rind was debulked maintaining the bundle. The skin was closed loosely over a drain with plans for re-exploration.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative view showing extensive necrosis of flexor muscles.

Figure 2.

Fungus encasing ulnar neurovascular bundle.

Postoperatively, the patient was maintained on an aggressive antimicrobial regimen of caspofungin, voriconazole, vancomycin, and cefepime and taken back to the operating room on postoperative day #2 for further debridement. The infective process was found to encase the median nerve, flexor carpi ulnaris tendon, and flexor carpi radialis tendon. The wound was packed and dressing changes were performed with half-strength sodium hypochlorite solution three times a day.

Histologic staining of tissue from the skin biopsy and intraoperative specimens demonstrated invasive fungal elements. Tissue cultures grew A. ustus sensitive only to caspofungin. Amputation of the infected extremity was considered given the high mortality associated with A. ustus infections but this was deferred to allow for optimization of the patient's antimicrobial regimen and modulation of the patient’s immunosuppressive regimen. Two additional debridement procedures were performed which decreased the fungal load and the patient’s immunosuppression was radically reduced.

After receiving further sensitivities and reviewing the literature on disseminated A. ustus infections, the patient was placed on a regimen of high dose caspofungin, terbinafine, and lipid-complex amphotericin B. His heart was closely monitored but there was no evidence of rejection with the dramatic decrease in his antirejection regimen. The patient improved clinically and healed his wounds secondarily. Serum galactomannan levels were followed monthly and consistently decreased as the patient continued to improve while on antifungal agents.

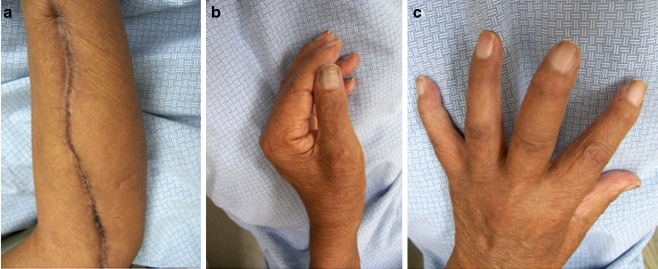

The patient was seen 7 months after discharge and was found to have well-healed incisions (Fig. 3). He had decreased sensation over the volar surface of his wrist and weak intrinsics with abduction of the index finger of 4/5. Additional range of motion deficits included lack of active flexion of the middle, ring, and small fingers and thumb. His fingers demonstrated residual swelling likely secondary to the extensive dissection and disruption of lymphatics on the volar forearm. The patient is currently using the hand as a helper hand and notes daily improvements in his function. The patient has had no recurrence of this infection and intends to undergo future tendon transfer procedures to restore active finger flexion of his fingers.

Figure 3.

Seven-month postoperative photographs showing healed incision after secondary closure (a), intact pinch grasp (b), and intact intrinsic muscle function (c).

Discussion

Aspergillus species are commonly cultured from cutaneous infections in immunocompromised patients. In the upper extremity, primary cutaneous aspergillosis is often associated with skin injuries such as burns, surgical wounds, or sites of IV or catheter insertion and typically presents as erythema and induration progressing to necrosis [1, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20]. Treatment depends on the underlying condition of the patient but typically involves topical and/or systemic antifungal chemotherapy plus surgical debridement when clinical indicated [21].

In contrast, disseminated invasive aspergillosis resulting in secondary cutaneous or soft tissue lesions is less common and more severe. Approximately 5–11% of disseminated Aspergillus infections involve the skin [11, 25]. Invasive aspergillosis of the hand requiring amputation has been described in children being treated for hematologic malignancies [11, 14].

We present a case of a 61-year-old patient who developed a disseminated infection involving the hand, lung, and posterior thigh with a rare form of Aspergillus known as A. ustus. Since 1970, only 27 cases of disseminated A. ustus infections have been reported [4, 13, 16, 17, 19, 24, 26, 27]. The fungus is found in food, soil, and indoor air environments and is believed to be an emerging nosocomial pathogen, particularly among transplant patients [16, 23]. It is characteristically resistant to multiple antifungal medications and may have an associated mortality rate as high as 50% [9, 17, 24].

There are no standardized diagnostic or treatment protocols for A. ustus. However, as with any infection in an immunocompromised patient, cultures for bacteria, fungi, viruses, and atypical pathogens should be performed. A serum galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or (1,3)-β-d glucan assay may be helpful for diagnostic purposes as well as for monitoring postoperatively as levels have been shown to correlate with clinical course [5, 24]. Involvement of experts in infectious disease is paramount as empiric treatment for a variety of organisms is often needed.

In the treatment of A. ustus, the antimicrobial regimen used in this case (caspofungin, intravenous amphotericin B, and topical terbinafine cream) has been successful in other reports [22, 24]. Dressing changes with sodium hypochlorite (also known as Dakin’s solution) may be a useful adjunct to antifungal therapy as the solution has been shown to have activity against Aspergillus species in vitro [2]. Reducing immunosuppression plays the vital role in managing these patients allowing for restoration of the patient’s ability to fight opportunistic pathogens. The issue should be promptly discussed with the team administering immunosuppressive agents.

While the role of surgery as it relates to A. ustus infections remains to be determined, treatment success has been reported when antifungal agents have been used alongside lung resection [3]. In addition, it is clear that surgical biopsy can facilitate early diagnosis, which is a key determinant of prognosis for patients with invasive aspergillosis in general [7].

Hand surgeon must be aware of the atypical and aggressive nature of infections that occur in transplant patients and others who are immunocompromised. The need for early surgical intervention and multiple debridement procedures should be recognized. This case also illustrates the importance of collaboration between the hand surgery, infectious disease, and transplant teams in coordinating care for immunocompromised patients with unique hand infections. With early diagnosis, multiple debridements, aggressive antimicrobial chemotherapy, and careful modulation of immunosuppression, one may be able to achieve outcomes more functional than that of amputation.

References

- 1.Allo MD, Miller J, Townsend T, Tan C. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis associated with Hickman intravenous catheters. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710293171802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo R, Goncalves Rodrigues A, Pina-Vaz C. Susceptibility pattern among pathogenic species of Aspergillus to physical and chemical treatments. Med Mycol. 2006;44:439. doi: 10.1080/13693780600654414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzola A, Passweg JR, Habicht JM, Bubendorf L, Tamm M, Gratwohl A, et al. Use of lung resection and voriconazole for successful treatment of invasive pulmonary Aspergillus ustus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4805. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4805-4808.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balajee SA, Houbraken J, Verweij PE, Hong SB, Yaghuchi T, Varga J, et al. Aspergillus species identification in the clinical setting. Stud Mycol. 2007;59:39. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.59.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretagne S, Marmorat-Khuong A, Kuentz M, Latgé JP, Bart-Delabesse E, Cordonnier C. Serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen testing by sandwich ELISA: practical use in neutropenic patients. J Infect. 1997;35:7. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(97)90833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlile JR, Millet RE, Cho CT, Vats TS. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a leukemic child. Arch Dermatol. 1980;114:78. doi: 10.1001/archderm.114.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denning DW, Stevens DA. Antifungal and surgical treatment of invasive aspergillosis: review of 2, 121 published cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:1147. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estes SA, Hendricks AA, Merz WG, Prystowsky SD. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:397. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gene J, Azon-Masoliver A, Guarro J, et al. Cutaneous infection caused by Aspergillus ustus, an emerging opportunistic fungus in immunosuppressed patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1134. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1134-1136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman ME, Fithian EC, Behrens C, Bissinger J, Fracaro M, Neu HC. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in six leukemic children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:313. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(85)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg B, Eversmann WW, Eitzen EM. Invasive aspergillosis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 1982;7:38. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt SJ, Nagi C, Gross KG, Wong DS, Mathews WC. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis near central venous catheters in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1229. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.9.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwen PC, Rupp ME, Bishop MR, Rinaldi MG, Sutton DA, Tarantolo S, et al. Disseminated aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus ustus in a patient following allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplantation. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3713. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3713-3717.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones NF, Conklin WT, Albo VC. Primary invasive aspergillosis of the hand. J Hand Surg. 1986;11A:425. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarty JM, Flam MS, Pullen G, Jones R, Kassel SH. Outbreak of primary cutaneous aspergillosis related to intravenous arm boards. J Pediatr. 1986;108:721. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(86)81051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panackal AA, Imhof A, Hanley EW, Marr KA. Aspergillus ustus infections among transplant recipients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:403. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.050670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavie JC, Lacroix DG, Hermoso M, Robin M, Ferry C, Bergeron A, et al. Breakthrough disseminated Aspergillus ustus infection in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients receiving voriconazole or caspofungin prophylaxis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4902. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4902-4904.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prystowsky SD, Vogelstein B, Ettinger DS, Merz WG, Kaizer H, Sulica VI, et al. Invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609162951206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saracli MA, Mutlu FM, Yildiran ST, Kurekci AE, Gonlum A, Uysal Y, et al. Clustering of invasive Aspergillus ustus eye infections in a tertiary care hospital: a molecular epidemiologic study of an uncommon species. Med Mycol. 2007;45(4):377–84. doi: 10.1080/13693780701313803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stiller MJ, Teperman L, Rosenthal SA, Riordan A, Potter J, Shupack JL, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Aspergillus ustus in a 62-year-old liver transplant recipient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:344. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burik JA, Colven R, Spach DH. Cutaneous aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3115. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3115-3121.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vagefi PA, Cosimi AB, Ginns LC, Kotton CN. Cutaneous Aspergillus ustus in a lung transplant recipient: emergence of a new opportunistic fungal pathogen. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:131. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varga J, Houbraken J, Lee HA, Verweij PE, Samson RA. Aspergillus calidoustus sp. nov., causative agent of human infections previously assigned to Aspergillus ustus. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:630. doi: 10.1128/EC.00425-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verweij PE, Bergh MF, Rath PM, Pauw BE, Voss A, Meis JF. Invasive Aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus ustus: case report and review. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1606. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1606-1609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walmsley S, Devi S, King S, Schneider R, Richardson S, Ford-Jones L. Invasive Aspergillus infections in a pediatric hospital: a ten year review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:673. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss LM, Thiemke WA. Disseminated Aspergillus ustus infection following cardiac surgery. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80:408. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/80.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yildiran ST, Mutlu FM, Saracli MA, Uysal Y, Gonlum A, Sobaci G, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis caused by Aspergillus ustus in a patient following cataract surgery. Med Mycol. 2006;44:665. doi: 10.1080/13693780600717161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]