Abstract

Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP) is a rare cartilaginous neoplasm that often presents in the long bones of the hands and feet. BPOP is a benign but locally aggressive fibro-osseous mass that has striking clinical, radiographic, and histologic similarities with osteochondroma. Differentiating between the two lesions is important as BPOP often requires more extensive surgical resection and has a higher recurrence rate compared to osteochondroma. This report presents two cases of BPOP where initial clinical diagnosis of osteochondroma was made even after appropriate imaging and histologic samples were evaluated. This report reviews clinical, radiographic, and histologic characteristics that can differentiate between the two lesions.

Keywords: Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation, Bone tumor, Misdiagnosis, Nora’s lesion, Osteochondroma

Introduction

Cartilaginous neoplasms of the musculoskeletal system represent a wide variety of lesions with varying clinicopathologic behaviors. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP) was first described by Nora in 1983 [9]. Nora’s lesion, as it is occasionally referred to, was originally described as a rare, benign osseous mass found primarily in the hands and feet. The mass is a fibro-osseous proliferation with a cartilaginous cap and is grossly similar in appearance to an osteochondroma. BPOP differ from osteochondromas in that they spare the distal phalanges, are not necessarily located in the metaphyseal region, and do not generally have medullary continuity between the native bone and the lesion [1, 7, 9]. In addition, BPOP has a dramatically higher frequency of recurrence, reported to be 20–55% [1, 7, 9]. Due to their similarities, a BPOP lesion can be misdiagnosed as an osteochondroma. Being able to correctly differentiate between the two lesions is important is surgical planning as BPOP requires more aggressive resection and possible reconstruction. The patient should also be counseled regarding an increased rate of recurrence with BPOP. In this report, we describe two patients whose lesions were originally misdiagnosed as osteochondromas. Using these cases, we review the distinguishing clinical, radiographic, and histologic features that differentiate the two lesions.

Case Number 1

A 39-year-old female was referred to the Orthopedic Clinic for evaluation of a left middle finger metacarpal lesion. She had previously undergone resection of a lesion in the same location 5 months previous under the care of a different surgeon. Original pathology was read as an osteochondroma. Shortly after resection, the patient noted rapid recurrence of the mass in the same location and was referred for evaluation. She complained of pain over her distal middle finger metacarpal associated with mild proximal radiation of pain.

She had no other previous surgeries in her affected hand. On physical exam, she was noted to have a well-healed dorsolateral incision overlying a prominent, firm mass in the distal-most aspect of the third metacarpal. The mass was tender, and her metacarpophalangeal (MCP) range of motion was 0/80° compared to 0/90° on the contralateral side. Sensibility and motor strength in the middle finger was normal, and her finger was well-perfused. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted.

Imaging prior to her initial resection was reviewed. Plain films showed an expansile lesion over the ulnar aspect of the distal third metacarpal (Fig. 1). It was difficult to determine if there was medullary continuity with the lesion. By report, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to the initial resection revealed an ulnar-based lesion of the neck of the third metacarpal that was approximately 1 × 1 cm in its greatest dimension. The lesion appeared to have a corticated rim with a cartilaginous cap.

Figure 1.

Shows an expansile lesion over the ulnar aspect of the distal third metacarpal.

Imaging done 5 months after her initial resection showed a lesion that was similar in appearance and location to the lesion that had been previously resected. To better assess the anatomy of the lesion, a computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained. It showed a 4 × 10 × 12 mm focus of mature bone formation along the ulnar side of the distal third metacarpal with no evidence for cortical destruction or communication with the marrow space. Given lack of marrow space communication, the appearance was not consistent with an osteochondroma. The possibility of bizarre periosteal osteochondromatous proliferation was discussed with the patient, and repeat excision was recommended.

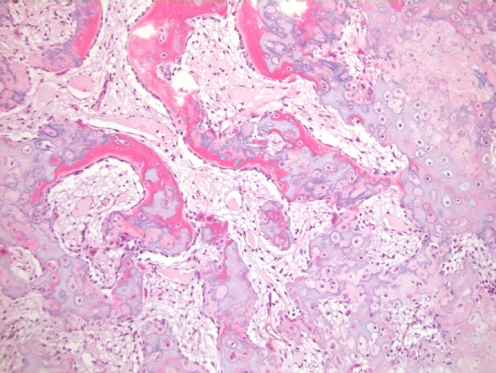

Pathology evaluation showed that the lesion exhibited irregular osseous-cartilaginous interfaces, with occasional bizarre nuclei (Fig. 2). The final interpretation was that the lesion was consistent with a benign osteochondromatous proliferation.

Figure 2.

Medium power view showing cellular cartilage with irregular calcification admixed with fibroblastic tissue. The cartilage is undergoing endochondral ossification with new bone lined by benign activated appearing osteoblasts.

The patient underwent wide excision 7 months after the second resection. The resection was carried out through the previously used dorsal incision. Extensor tenolysis was performed. The bony lesion was excised with a hemiresection of the metacarpal. An iliac crest corticocancellous allograft was then fashioned to fit the bony defect and secured with screws (Fig. 3). At her 1-year follow-up, she had no evidence of tumor recurrence. Her MCP joint range of motion was mildly limited at 10–80°. She had no complaints of pain. There was radiographic evidence of a well-healed graft.

Figure 3.

Post-operative reconstruction radiographs.

Case Number 2

The patient was a 38-year-old right-hand-dominant male who presented to us with a recurrent left long finger mass. He had undergone excision of a bony mass in the same location 16 months previously. The mass was determined to be an osteochondroma by pathology assessment. Shortly after excision, he noted recurrent swelling, and radiographs had shown a recurrence of the bony mass. He stated that the mass did not limit his activities, and it was minimally painful. He had no numbness or tingling distally.

On physical exam of his left hand, there was a 1 × 1 cm mass that protruded 5 mm over the ulnar aspect of the long finger at the base of the middle phalanx. He had normal range of motion and intact neurovascular function.

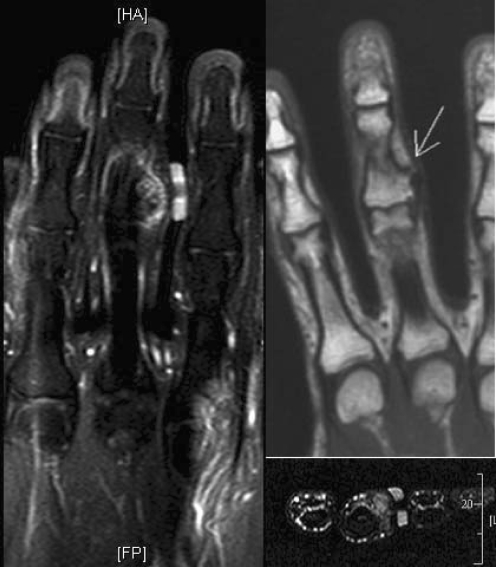

Imaging from 17 months after his excision demonstrated a bony mass extending from the base of the middle phalanx of the long finger on the ulnar aspect (Fig. 4). There was no cortical destruction. MRI showed that the mass was extracortical and did not involve the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 5). Given the rapid recurrence of the lesion and concern for malignant potential, repeat excision was recommended.

Figure 4.

Bony mass extending from the base of the middle phalanx of the middle finger on the ulnar aspect.

Figure 5.

Magnetic resonance imaging—coronal T1 FS (left), coronal T1 (upper right) and axial T2 FS (lower right). Demonstrates internal T2 hypointensity, represents calcification, and abuts the flexor tendon. There is heterogeneous contrast enhancement, mainly at the periphery of the lesion.

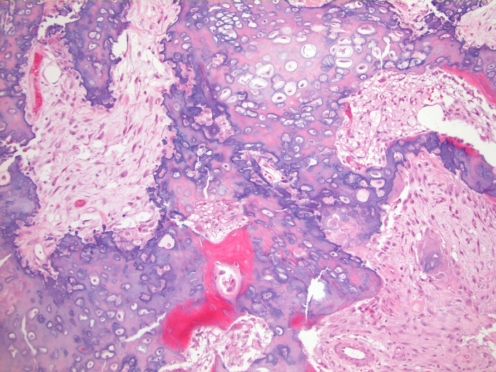

Intraoperatively, the patient’s initial mid axial incision was used and extended with a Brunner incision. The mass protruded between the artery and nerve and required complex dissection and neurolysis. The flexor tendon sheath was released at the level of the A-3 and C-1 pulleys sparing the A-2 and A-4 pulleys. The mass was noted to extend to the level of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. The mass was excised along with a small margin of normal bone and soft tissue, including a portion of the collateral ligament and volar plate, which was reconstructed using a rotation of the volar plate and Micromite bone anchors (Conmed Linvatec, St. Petersberg, FL, USA). Final pathology of the excised lesion was consistent with bizarre periosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Medium power view that shows cellular cartilage with irregular outlines admixed with fibroblastic spindle cells. Endochondral ossification of lesional cartilage is seen below center.

Discussion

BPOP and osteochondromas are strikingly similar in clinical presentation. Patient history may be helpful in differentiating the two entities. BPOP most commonly occurs in the fourth decade, while osteochondromas are most commonly diagnosed in the second and third decades [5]. However, either lesion can occur over a larger age span. Given that these age spans are similar and that the age spans can overlap, age is not a reliable discriminating clinical factor. Similarly, the presence or absence of pain is not helpful in that both pathologic processes may or may not have pain as a symptom. In addition to their similar clinical presentation, BPOP and osteochondromas can also have similar radiographic and histologic appearances.

Radiographic Appearance

BPOP lesions of the hand involve the phalanges in 92% of cases and are typically located in the diaphysis and metaphysis [4]. All lesions originate from the periosteal aspect of an intact cortex of the affected bone. This is in contrast to the key radiographic feature of osteochondromas, which is the presence of continuity between the lesion and the underlying medullary cavity. Careful axial CT or MRI can be helpful when radiographs are inconclusive though will not always be able to always rely on medullary continuity as the discriminating factor. Recently, four cases have been described where histologically proven BPOP lesions demonstrated communication of the lesion with the underlying medullary cavity on radiographs and CT [10]. This challenges the notion that the presence of medullary continuity will always distinguish osteochondromas from BPOP lesions and raises the possibility that relying solely on this criterion may lead to misdiagnosis of BPOP lesions as osteochondromas. In the two cases we have presented, plain radiographs were not conclusive in determining the presence or absence of medullary continuity, but axial imaging (CT scan and MR) demonstrated that the cortex was not disrupted, and that there was no medullary continuity between the lesion and the underlying bone. On MRI, BPOP has a low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and a high signal intensity on T2-weighted and short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) sequences and is noted to not involve the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 5) [11].

Histology

Histologically, BPOP has three components: cartilage, bone, and fibroblastic spindle cells. The cartilage may form a cap very similar to that of an osteochondroma. The cartilage is arranged geographically or as irregular islands with variable mineralization undergoing endochondral ossification. In BPOP, chondrocytes are ‘bizarre’ in appearance with enlarged nuclei with distinct nucleoli and open or unpacked chromatin. The chondrocyte atypia may even approximate the appearance of chondrosarcoma [9]. In the background, there are numerous fibroblastic spindle cells which may also have mild cytological atypia [7]. Bony trabeculations in BPOP are benign appearing but very irregular in orientation. Meneses et al. described the bony trabeculae as having a blue color that is more evident at the interface with cartilage [7]. Osteochondromas, however, have a more regular arrangement of the trabeculae of bone, oriented at 90° to the cartilage cap [3, 6]. In spite of this, some regions of BPOP lesions may have less irregularity and a histologic appearance similar to osteochondromas [10]. BPOP will have fibroblastic tissue not seen in osteochondroma, and the chondrocyte atypia in BPOP is not present in osteochondroma.

Management

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for BPOP lesions [7, 12]. Adjuvant cryotherapy has also been suggested [6]. Excision will alleviate symptoms related to mass effect such as restricted range of motion or pain and tenderness. In spite of surgical excision, BPOP displays a high rate of recurrence with as many as 50% of patients having a recurrence within 2 years and almost half of those having a second recurrence [9]. As with other musculoskeletal lesions, wide excision as opposed to intralesional curettage can decrease recurrence risk, a finding demonstrated in this small series. A key feature to the preoperative planning is the preparation to reconstruct either the bone or ligaments in order to achieve the required margin. Excising the underlying periosteal tissue and suspicious appearing cortex has been shown to be beneficial in preventing recurrence [8]. While BPOP is a benign lesion, there has been a case report of a distal fibula fibrosarcoma in an 18-year-old woman who had a concomitant BPOP at the same site [2]. However, no evidence of causality or malignant transformation has been shown.

Conclusion

Osteochondroma and BPOP can have subtle differences that may lead to misdiagnosis as was described in our two cases. Careful assessment of the clinical features, signs on imaging, and histologic characteristics described may prevent misdiagnosis in other cases and prompt more aggressive initial management.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimers No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. No grant or other financial assistance was used in creating this article.

Contributor Information

Aaron M. Chamberlain, Phone: +1-801-6314122, FAX: +1-206-2570464, Email: amc12@u.washington.edu

Jason S. Weisstein, Email: weisstei@u.washington.edu

References

- 1.Brien EW, Mirra JM, Luck JV., Jr Benign and malignant cartilage tumors of bone and joint: their anatomic and theoretical basis with an emphasis on radiology, pathology and clinical biology. II. Juxtacortical cartilage tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s002560050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi JH, Gu MJ, Kim MJ, et al. Fibrosarcoma in bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:44–47. doi: 10.1007/s002560000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange EE, Pope TL, Jr, Fechner RE, et al. Case report 428: bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP) Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16:481–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00361482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhondt E, Oudenhoven L, Khan S, et al. Nora’s lesion, a distinct radiological entity? Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:497–502. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flint JH, McKay PL. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation and periosteal chondroma: a comparative report and review of the literature. J Hand Surg. 2007;32:893–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindeque BG, Simson IW, Fourie PA. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation of a phalanx. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;110:58–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00431369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meneses MF, Unni KK, Swee RG. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation of bone (Nora’s lesion) Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:691–697. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelsen H, Abramovici L, Steiner G, et al. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora’s lesion) in the hand. J Hand Surg. 2004;29:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nora FE, Dahlin DC, Beabout JW. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferations of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:245–250. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rybak L, Abramovici L, Kenan S, et al. Cortico-medullary continuity in bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation mimicking osteochondroma on imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torreggiani WC, Munk PL, Al-Ismail K, et al. MR imaging features of bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation of bone (Nora’s lesion) Eur J Radiol. 2001;40:224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(01)00362-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twiston Davies CW. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation in the hand. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:648–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]