Abstract

The pretreatment of human dendritic cells with interferon-β enhances their immune response to influenza virus infection. We measured the expression levels of several key players in that response over a period of 13 h both during pretreatment and after viral infection. Their activation profiles reflect the presence of both negative and positive feedback loops in interferon induction and interferon signaling pathway. Based on these measurements, we have developed a comprehensive computational model of cellular immune response that elucidates its mechanism and its dynamics in interferon-pretreated dendritic cells, and provides insights into the effects of duration and strength of pretreatment.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are essential in the establishment of the innate immune response and the triggering of adaptive immunity (1). Activated DCs undergo a process of maturation involving the upregulation of major histocompatibility complex molecules, secretion of various cytokines and chemokines, and migration to draining lymph nodes to activate T-cells (2).

DCs can detect and respond to viral infection through two different pathways: a Toll-like-receptor (TLR)-dependent and a TLR-independent pathway. The TLR-dependent pathway utilizes TLR 3, 7/8, and 9 to recognize extracellular or endosomal viral double-stranded RNA, single-stranded RNA, and CpG DNA, respectively (3). The TLR-independent pathway includes melanoma-differentiation-associated gene-5 and retinoic-acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I), which both detect cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA, whereas RIG-I also recognizes 5′-triphosphate RNAs (4,5). Regardless of which pathway is followed, DC activation entails the induction and secretion of type I interferon (IFN), which plays a key role in the antiviral immune response (6). Secreted type I IFN activates the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway in the same cell or other cells through an autocrine or a paracrine loop similar to that described in Shvartsman et al. (7). The activation of the IFN-signaling pathway establishes an antiviral state in target cells by inducing the transcription of numerous IFN-responsive genes (8).

All pathogenic viruses have developed various strategies to partially block and circumvent the IFN response (9). It is expected that the innate immune system has similarly devised mechanisms to overcome viral inhibitory effects. In vitro experiments have shown that the secretion of type I IFN from DCs after influenza infection is effectively blocked by the influenza NS1 protein, a potent IFN antagonist (10,11). However, the corresponding immune response is strong (12), suggesting that the antagonism is somehow overcome in vivo. This could result from exposure of immune cells to IFN before virus encounter, which has been shown to enhance the DC response to virus challenges (13–16). Moreover, in a mouse model of influenza infection, we have evidence that monocytes recruited to the site of infection display an interferon signature before exposure to virus in the lungs (T. Hermesh, B. Moltedo, T. M. Moran, and C. B. Lopez, unpublished). It is possible that the interferon may be released by plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) (16). A recent study also indicates that cytokines/chemokines secreted from virus-infected DCs, including type I IFNs, could induce a primed state among the uninfected DCs through paracrine signaling, making these DCs more resistant and more responsive to future infection than naïve DCs (17). Since IFN pretreatment of DCs alone does not induce IFNs, the enhanced IFN induction in IFN-pretreated DCs after virus infection must be attributed to the upregulation of one or more IFN-stimulated genes. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying cellular responses to IFN exposure and virus infection, we constructed a comprehensive model of the cellular immune response.

Interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 7 is one of the IFN-stimulated genes that has been reported as a key regulator of type I IFN induction in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and pDCs (18). IRF7 functions as an important component of the positive feedback loop for virus-triggered type I IFN induction (19,20). It is induced through the JAK/STAT pathway upon IFN stimulation (19,21) and activated through the RIG-I signaling pathway, similar to IRF3 (22). Phosphorylated IRF7 (IRF7P) translocates into the nucleus in the form of a homodimer or heterodimer with phosphorylated IRF3 (23,24) and enhances both IFN-β and IFN-α induction (18,19,21,25). We consider the upregulation of IRF7 to be the main cause of enhanced IFN induction in IFN-pretreated human DCs infected by the influenza PR8 virus.

The IFN signaling pathway itself has been extensively studied (see review in Platanias (26)) and modeled (27,28), but its involvement in the positive feedback, and in particular the role played by IRF7 in the context of virus-triggered type I IFN induction, has not been well characterized. Our mathematical model integrates IFN-induced IRF7 production and virus-triggered IFN induction. It encompasses IFN secretion into extracellular space, receptor activation, and cytoplasmic and nuclear reactions tied together through feedback loops. It is the first model—to the best of our knowledge—that attempts such a comprehensive description of the dynamics of the immune response. From a methodological standpoint, the model is distinguished by the fact that its elements are limited, as much as possible, to those components, proteins or mRNA, that are actually being measured in IFN-pretreated human DCs infected by PR8. We obtained quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and high-resolution imaging flow cytometry measurements in both the pretreatment regime and after viral infection over a time span of 13 h. The corresponding time courses of multiple key mediating species in the type I IFN induction loop provide strong constraints on model building. These constraints are much more stringent than those imposed by the known monotonously increasing IFN-α/β concentrations, because some time courses, such as that of nuclear phosphorylated STAT (STATPn), show sizable variations within the observed time span (see Fig. 2). Our modeling results predict two important saturation threshold values for in vitro IFN pretreatment dosage and pretreatment time and provide insight into the in vivo DC temporal responses to virus infection.

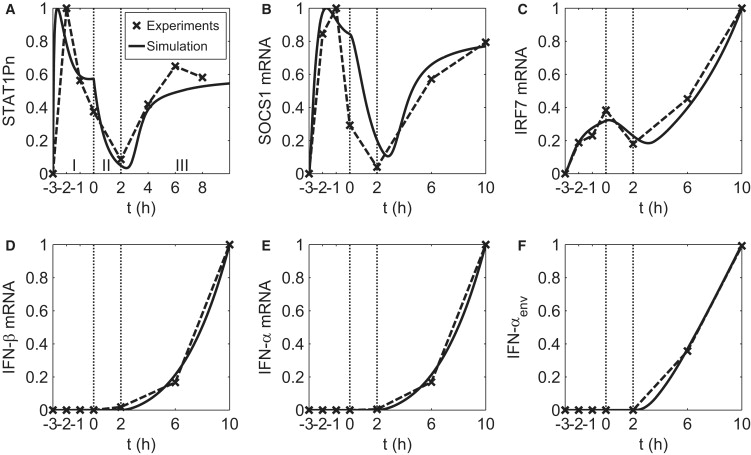

Figure 2.

Experiment and simulation of IFN-pretreated DC response to influenza PR8 virus infection. The experimental time course data points are marked by crosses and connected with dashed lines after normalization with respect to the corresponding maximum for each species in (A) nuclear protein, (B–E) mRNA, and (F) secreted protein. The label of the horizontal axis represents the time (in hours) of measurement. The simulation result is plotted with solid lines and normalized to the corresponding maximum. The temporal response of each species is divided into three stages according to the change in extracellular IFN level (as discussed in the text), separated by vertical lines. Pretreatment time extends from t = −3 to t = 0 h. Viral infection (PR8 virus) takes place at t = 0 h. The DCs used in the experiment are from four different donors, denoted as donors 1–4 in this legend. The data points for t = −3–0 h in A are the average results from donors 1–3. The data points for t = 2–8 h in A are from donor 1. The data points for t = −3–0 h in B–F are the average results from donors 2 and 3. The data points for t = 2–10 h in B–F are from donor 4.

Materials and Methods

Experiments

Isolation and culture of human DCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) from buffy coats of healthy anonymous human donors (New York Blood Center, New York, NY). CD14+ cells were immunomagnetically purified using anti-human-CD14 antibody-labeled magnetic beads and iron-based Midimacs LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After elution from the columns, CD14+ cells were plated (1 × 106 cells/ml) in DC medium (RPMI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) or 4% human serum (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen)) supplemented with 500 U/ml human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 1000 U/ml human interleukin-4 (IL-4) (Peprotech). Cells were incubated for 5–6 days at 37°C. Our cultured DCs were routinely 95–98% positive for CD11c as tested by flow cytometry.

Infection and treatment of DCs

After 5–6 days in culture, the conventional DCs were pretreated for 3 h with 200 U/ml IFN-β (PBL, Piscataway, NJ) or left alone. After 3 h, both nontreated and IFN-treated cells were spun down and medium was completely removed. Cells were resuspended in DC media (RPMI (Invitrogen), 4% human serum (Cambrex), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen)) at 1 × 106 cells/ml. The samples were split in two, one of each sample infected with influenza PR8 virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5. At the time point listed, cells were removed from total samples for qRT-PCR, ELISA, and high-resolution imaging flow cytometry quantification. Depending on the experiment, the time points of infection examined were 2 and 1 h before infection, immediately before infection, and either 2, 6, and 10 h or 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after infection.

Imaging flow cytometry

Cells were fixed in a final concentration of 1.5% paraformaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich). After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 100% methanol for 15 min at 25°C and washed three times with staining buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Samples were then incubated with monoclonal antibodies against STAT1 and phosphorylated STAT1 (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and DRAQ-5, a nuclear dye (Biostatus, Shepshed, UK). Cells were then assayed with the Image Stream 100 (Amnis, Seattle, WA) imaging flow cytometer. The degree of phosphorylation of STAT1, as well as the degree of nuclear translocation of STAT1 or phosphorylated STAT1, was analyzed with the help of the IDEAS software (Amnis). The increase of fluorescence caused by the fluorophore conjugated antibody against phosphorylated STAT1 was used as a measurement for the phosphorylation of STAT1. A normalized Pearson's correlation of the pixel intensities of the nuclear dye and STAT1 or phosphorylated STAT1 was used to calculate a translocation score. The degree of translocation was then calculated by the difference of the medians of the translocation scores of a specific time point minus the negative control sample divided by the sum of standard deviations of both samples.

Capture ELISAs

Supernatants were isolated after cell pelleting, and capture ELISAs for IFN-α were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (PBL). Plates were read in an ELISA reader from Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT. All samples were assayed in duplicate or triplicate.

RNA extraction from human DCs

Samples of at least 0.5 × 106 cells/sample were pelleted, and RNA was isolated and treated with DNase by using an Absolutely RNA RT-PCR microprep kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE).

Quantitative real-time PCR

qRT-PCR of the extracted RNAs was performed by using a previously published SYBR green protocol (11) with an ABI7900 HT thermal cycler by the Mount Sinai Quantitative PCR Shared Research Facility. Each transcript in each sample was assayed in triplicate, and the mean cycle threshold was used to calculate the x-fold change and control changes for each gene. Three housekeeping genes (actin, Rps11, and tubulin) were used for global normalization in each experiment. Data validity was determined by modeling of reaction efficiencies and analysis of measurement precision, as described previously (11).

Model

Our goal is to develop a model of type I IFN induction in IFN-pretreated DCs after virus infection. Instead of constructing an extensive model by assembling all the available information from the literature, we take the approach of modeling the measured temporal behavior of only a few known key mediators of the IFN response to virus infection. The model, with a minimal number of free parameters, aims to capture the essential characteristics of the experimental time course data. For simplicity, various assumptions are made. For example, STAT1 and STAT2 are not differentiated and are modeled as one species denoted STAT. A detailed discussion of the reaction network and derivation of the equations for our model can be found in the Supporting Material.

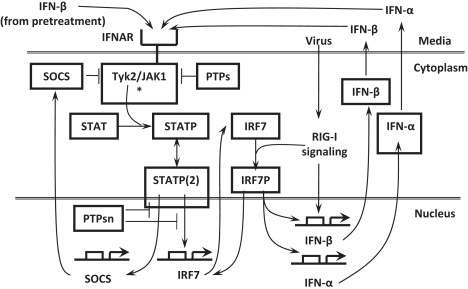

As shown in the network in Fig. 1, when DCs are pretreated with IFN, IFN binds to the IFN-α/β receptors (IFNARs) and activates the receptor-associated kinase JAK1 and Tyk2 (29–31). STATs (STAT1 and STAT2) are recruited to the activated receptor complex and phosphorylated (32). Phosphorylated STAT (STATP) dimers (including STAT1P homodimer and STAT1P/STAT2P heterodimer) translocate into the nucleus (29,33,34). The STATP dimers are subject to dephosphorylation in the nucleus by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) (35,36). Nuclear STATP dimers lead to the induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) genes (such as SOCS1, mediated through IRF1 (37)). Induced SOCS proteins inhibit the kinase activity of the receptor complex (e.g., by interacting with either Tyk2 or IFNAR1 (38)) and negatively regulate the IFN signaling pathway. IRF7 is induced by the interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 consisting of STAT1P, STAT2P, and IRF9 (19,21).

Figure 1.

Induction of IFNs after virus infection in IFN-β pretreated human DCs. IFN-β, after binding to IFNAR, engages the JAK/STAT pathway, leading to STAT phosphorylation and production of IRF7 and SOCS. The latter acts back negatively on JAK/STAT pathway activation. Viral infection is detected by RIG-I and leads via IRF7 activation to induction and secretion of IFN-β/α, which bind to IFNAR in a positive feedback loop. Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) act in the cytoplasm and nucleus.

When DCs are infected with influenza virus after IFN pretreatment, its detection by RIG-I triggers the RIG-I signaling pathway, leading to the activation and subsequent nuclear translocation of IRF7 (22–24) and other enhanceosome components (39). In the nucleus, the activated enhanceosome components bind to the IFN-β promoter in a cooperative manner to form the enhanceosome, which promotes the induction of the IFN-β gene (40). IRF7P also promotes the induction of various IFN-α genes (18,19,25). Induced IFN-α and IFN-β are secreted in the media and are capable of binding to the IFN receptors of the same cell or other cells through an autocrine or a paracrine loop.

The final form of the model (see Text S2 in the Supporting Material) consists of eight coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for the eight concentrations STATP(2)n (phosphorylated STAT dimer in the nucleus), SOCSm (SOCS mRNA), IRF7m (IRF7 mRNA), IRF7Pn (phosphorylated IRF7 in the nucleus), IFN-βm and IFN-βenv (IFN-β mRNA and IFN-β in the environment), and IFN-αm and IFN-αenv (IFN-α mRNA and IFN-α in the environment). These equations contain 19 parameters, of which 14 are fixed at values derived from biological considerations and five are used in fitting the eight model equations to the experimental data points, of which there are 29. The time courses of six model concentrations, namely STAT1Pn, SOCS1 mRNA, IRF7 mRNA, IFN-β mRNA, IFN-α mRNA, and IFN-αenv (see Fig. 2), were directly experimentally measured with seven, six, six, five, three, and two data points, respectively, available for parameter estimation. The experimental data of STAT1Pn, SOCS1 mRNA, and IRF7 mRNA show a rich temporal structure that constrains the parameters used in the fit.

Some important remarks concerning our model are:

-

1.

Our qRT-PCR data show that RIG-I is upregulated in a manner similar to that of SOCS1 and IRF7 upon IFN stimulation (Fig. S1), possibly as a result of shared induction by a complex associated with phosphorylated STATs. As RIG-I functions as the viral sensor of the RIG-I signaling pathway, it is possible that its upregulation could contribute to the enhanced induction of type I IFNs in IFN-pretreated DCs. However, data from a separate study on human DCs (J. Hu and J. Wetmur, unpublished) indicate that the protein levels of the IFN enhanceosome components downstream of RIG-I other than IRF7P (e.g., phosphorylated IRF3) do not show significant increase with RIG-I upregulation after virus infection, whereas the type I IFNs are induced at an accelerating rate. This suggests that RIG-I upregulation alone cannot account for the enhanced type I IFN induction in IFN-pretreated DCs, implying the participation of a different IFN-stimulated gene (or genes). In our model, this gene is assumed to be IRF7. We do not explicitly include the upregulation of RIG-I and possible upregulation of other upstream components in the RIG-I signaling pathway (41). We assume their upregulation functions to maintain a constant kinase level that activates the induced IRF7.

-

2.

The experimental data indicate an ∼2-h delay in the induction of detectable levels of IFN-β mRNA after infection, which is the time taken by activation of the RIG-I signaling pathway and IRF7. An arbitrary 2-h delay in IRF7 activation after virus infection is introduced in our model to account for this fact.

-

3.

The qRT-PCR data of IRF7 mRNA show increased induction after t > 2 h (Fig. 2 C) despite the flattening of STAT1Pn after t > 6 h (Fig. 2 A). This contrasts with SOCS1 mRNA (Fig. 2 B) and RIG-I mRNA data (Fig. S1) that follow STAT1P behavior. The degradation of IRF7 mRNA from t = 0–2 h suggests a typical half-life of 2 h for IRF7 mRNA. Thus, a much longer IRF7 mRNA half-life cannot be evoked to explain the enhanced IRF7 mRNA induction. However, it was reported that virus infection could activate IRF3 and IRF7, which form the virus-activated factor with coactivators CREB-binding protein and P300 and induce IRF7 independently of IFN signaling (42). We therefore included this positive feedback of IRF7 induction into our model to account for the enhanced IRF7 induction after virus infection. In the equation for IFN-β induction (see Text S1 in the Supporting Material), we neglect the term that would account for the case of infection without pretreatment. This term would be small and could be adjusted to fit the corresponding data. Because the influenza virus PR8 contains the potent immune response antagonistic protein NS1, the measured response (IFN, IRF7, RIG-I, etc.) in nonpretreated cells is very much suppressed (11,16).

-

4.

Since, in the experiment, the multiplicity of infection is <1, not all cells are infected by the virus, though all cells are pretreated. However, the environment created by the secretion of IFN from infected cells is the same for all cells. Therefore, the time courses of gene products induced in the JAK/STAT pathway are similar for both infected and uninfected cells. The exception is IRF7, which has both viral (through virus-activated factor) and JAK/STAT pathway induction. In the modeling, we consider only infected cells, and neglect the fact that the IRF7 data somewhat underestimates the amount of IRF7 at large times.

Model parameter estimation

Our model contains eight species (see Text S2 in the Supporting Material) and a total of 19 parameters. The parameter values were estimated through an iterative nonlinear least-square fitting to the experimental data (described below). The starting parameter values of mRNA induction, degradation, and protein translation rate constants were set to the corresponding typical values (see Table S1). For the remaining parameters, we set their starting values to physiologically reasonable numbers. The initial condition of our model corresponds to a state in which IFN-βenv is determined by the pretreatment dosage and the concentrations of the remaining seven modeled species are set to zero.

Error function and local parameter sensitivity

We defined the following error function for our least-square fitting:

where Xij (P) and Yij are the normalized simulation values evaluated at the parameter set P and normalized experimental data points, respectively. Normalization is to the maximal value over the respective time courses when the experimental data are given in arbitrary units and to the maximum of the experimental data for both simulation and experiment when the experimental data are given in physical units. The sum runs over all species (from 1 to m) and time points (from 1 to n).

For a given set of parameters, the sensitivity of the error function, E, to finite changes in the value of the ith parameter, pi, was estimated through a local parameter sensitivity, Si, defined as the relative change in E due to a 5% change in pi:

where E0 is the error function evaluated at the given parameter set. This local parameter sensitivity Si is used in our iterative least-square fitting procedure (described below) to select parameters for the model fitting to experimental data.

Iterative least-square fitting

We used the iterative procedure below for the nonlinear least-square fitting of our model to the experimental data, beginning with the parameter starting values:

-

1.

Compute local parameter sensitivity Si for all parameters individually at current values, as described above.

-

2.

Identify the parameter(s) with Si > 0.05 (an arbitrary threshold) but not in the set Pfit, which is the list of parameters to be optimized. Pfit is set to be empty at the beginning of optimization. When there is at least one parameter that satisfies the criteria, choose the parameter with the largest Si and add it to the set Pfit; otherwise, the fitting procedure is terminated.

-

3.

Perform a local optimization with respect to the parameters in Pfit while fixing the rest parameters at their current values. Use the optimized parameter values to update the current parameter set, then go to step 1.

The model simulation and optimization are performed in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) using the ODE solver “ode15s” and minimization routine “fminunc”.

For our model, the procedure terminated in five iterations. As a result, a total of five model parameters were optimized, whereas the remaining 14 parameters remain fixed at their starting values (see Table S1).

Confidence interval and identifiability

The 68% confidence interval (CI) for the optimized parameter values are computed according to Press et al. (43), using the equation

where H is the Hessian matrix, Hij = ∂2 χ2/∂pi∂pj, evaluated at the optimized parameter set and χ2 = E/σ2. Here, we have assumed a constant standard deviation for all experimental data points and estimated it with σ2 = Emin/(N − M), where Emin is the error function E evaluated at the optimized parameter set; N is the number of experimental data points, and M is the number of optimized parameters (43). The computed confidence intervals were normalized with respect to the corresponding optimized parameter values, and the resulting percentages were summarized in Table S1.

To determine the identifiability (44,45) of our model parameters, we chose the tolerance for the normalized 95% confidence intervals of identifiable parameters to be ±40% (45). Among the five optimized parameters, three are identifiable (vmax, τ2, and τ3) according to the selected tolerance, for which the 95% confidence intervals can be estimated as two times the 68% confidence intervals shown in Table S1.

Parametric sensitivity analysis

We carried out local parameter sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of parametric changes on the temporal system responses. The normalized sensitivity (NS) is computed for each variable in our ODE model with a finite difference approximation:

where y and p, respectively, denote the system response variables, namely, the species concentrations and parameters.

The parametric sensitivity analysis result is shown in Fig. S2 for four species. It shows that the induction of type I IFNs (Fig. S2 C) is most sensitive to the half-lives of STATP(2)n τ2 and SOCSm τ3 (especially ∼2–3 h after virus infection). This heightened sensitivity reflects the importance of the interplay between STATP and its inhibitor SOCS for the induction of type I IFNs, as the system mostly operates in a regime where the binding of the extracellular IFNs to the receptors quickly reaches saturation due to a predicted low threshold value (Fig. 3 A).

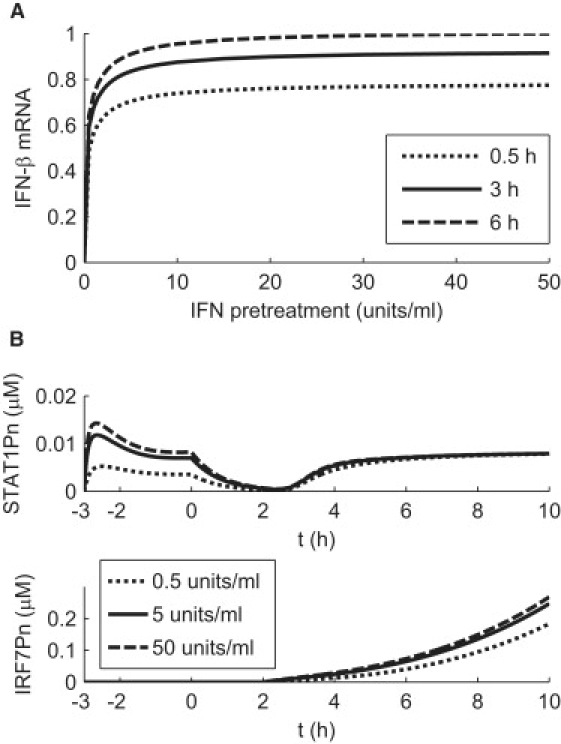

Figure 3.

Predicted dependence of IFN induction on IFN pretreatment conditions. (A) IFN mRNA levels are evaluated at t = 10 h for increasing IFN pretreatment dosages and indicated pretreatment times. The computed IFN mRNA levels are normalized by the value computed at the pretreatment condition of 50 U/ml dosage and 6 h of pretreatment. (B) Predicted temporal responses of STAT1Pn and IRF7Pn level at indicated pretreatment dosages for a pretreatment duration of 3 h.

Results and Discussion

Regulation of type I IFN induction by extracellular IFN

We now proceed to compare experimental and simulated results. Simulations are based on the network model shown in Fig. 1, the details of which are described in the Supporting Material.

As shown in Fig. 2, the intermediate species involved in the induction of IFN show richly varied and distinct temporal responses. For example, the level of nuclear phosphorylated STAT1 protein (STAT1Pn) in Fig. 2 A shows a prompt increase followed by a quick drop during the first 3 h of pretreatment, monotonically decreases until 2 h after virus infection, increases again up to t = 4 h, and eventually stabilizes. Our model is not only capable of reproducing such characteristics in temporal behavior, but, of more importance, provides a tool for understanding and exploring the mechanisms behind such complex dynamics.

Through modeling, we found that the extracellular IFN level in both the pretreatment and postinfection stages plays an essential role in the regulation of virus-triggered type I IFN production. Below, we explain how this occurs, and show how the interplay of extracellular IFN and intracellular IRF7 levels leads to the complex dynamical behavior shown in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2, A, D, and E, the upregulation of IFN mRNA at t > 2 h coincides with the simultaneous increase of STAT1P, which implies that the dynamics of IRF7-related reactions, namely, IRF7 phosphorlyation and translocation, and IRF7-promoted IFN induction, is fast. In addition, the sharp increase and decrease of STAT1P in the pretreatment stage implies fast phosphorylation as well as dephosphorylation. The temporal response of SOCS1 mRNA (Fig. 2 B) exhibits a tight correlation with that of STAT1P, suggesting that the degradation of SOCS1 mRNA is also fast. As the half-life of SOCS1 protein is short (1.5 h, as reported in Siewert et al. (46)), we expect the dynamics of SOCS1 protein to resemble that of its mRNA. Thus, because of the fast dynamics of the mediating signaling species, STAT1Pn, SOCS1 mRNA/protein, and IRF7 mRNA/protein, the overall signaling pathway is tightly regulated by the dynamics of receptor-ligand formation, which is determined by the level of IFN in the media.

We divide the overall process into three stages according to changes in the extracellular IFN level, as indicated in Fig. 2 A.

Stage I

The introduction of a constant level of extracellular IFN results in a prompt increase in the activated receptor complex (the kinase for STAT phosphorlyation) to a fixed level. The dynamics of STAT1Pn is governed by the interplay between STAT1Pn and SOCS proteins through a delayed negative feedback, resulting in a peaked STAT1Pn response associated with damped oscillations, as a delayed negative feedback is often associated with oscillatory behavior (47). IRF7 mRNA (Fig. 2 C) is regulated by phosphorylated STAT similarly to SOCS1. No IFNs are induced and secreted at this stage, as there is no virus infection.

Stage II

As IFN in the media is removed at t = 0 and virus added, the STAT1Pn level starts to decline at a faster rate because of the complete removal of its upstream kinase. Both IRF7 mRNA and SOCS1 mRNA continue to decrease due to constitutive degradation as the level of nuclear STAT1Pn decreases. Even though the cells are already infected by the virus, there is still no detectable level of IFN-β mRNA, probably due to the low virus copy number, antagonist activity of the influenza virus, and slow dynamics of enhanceosome assembly for IFN-β induction.

Stage III

When cell-secreted IFN triggers the IFN signaling pathway after t > 2 h, the overall dynamics is controlled by the slow secretion of IFN proteins before the saturation IFN level is reached (∼t = 6 h), when the amount of STATP levels off. For the period between t = 2 h and t = 6 h, the temporal responses resemble that of the extracellular IFN level, i.e., they show a monotonic increase, because the dynamics of mediating signaling species is fast (as discussed above) compared to the slow secretion of IFN. After saturation, the dynamics is once again controlled by the interplay between STAT1Pn and SOCS proteins. IRF7, on the other hand, keeps increasing because of autoinduction.

Applications of the model

We consider two applications of our model. To identify optimal conditions leading to maximal IFN response, we explore the influence of different IFN pretreatment conditions (dosage and duration) on IFN induction. We also simulate in vivo induction of IFN in DCs at the site of infection.

Different pretreatment conditions

Fig. 3 A shows that increasing pretreatment dosage or duration beyond some limits does not prepare a cell to better cope with viral infection. For fixed pretreatment duration, as shown in Fig. 3 A, IFN induction increases dramatically with IFN pretreatment dosage in the low-dosage regime (<5 U/ml) and quickly becomes insensitive to further increase in pretreatment dosage. Moreover, for dosages >5 U/ml, IFN induction is rather insensitive to pretreatment duration above 0.5 h. One can ask what aspects of the model determine the shapes in Fig. 3 A. The increase with dosage (for a given pretreatment time) of the percentage amount of induced IFN can be traced back to the corresponding responses of STAT1Pn, for which a strong dependence on dosage is apparent before infection (Fig. 3 B). This preinfection dosage dependence of STAT1Pn entrains a corresponding postinfection dependence in nuclear phosphorylated IRF7 (IRF7Pn) (Fig. 3 B), which ultimately is responsible for the observed dependence of IFN-β on pretreatment dosage in Fig. 3 A. Higher pretreatment dosages do not lead to more induced IFN because the IFN receptors are already saturated. Our model predicts a threshold value of ∼2 U/ml for the binding of extracellular IFN to the IFNAR complex of a human DC (corresponding to the value of parameter K1, as described in the Supporting Material), with a saturation level of ∼20 U/ml, 10 times the threshold value. As with dosage amount, an increase in pretreatment duration does not lead to significant gains in IFN induction. Saturation takes place with pretreatment duration as soon as dosage exceeds 5 U/ml (Fig. 3 A). The reason can again be traced back to STAT activation. When pretreatment duration increases, the STAT1Pn peak of Fig. 2 A moves to earlier times, allowing more time for the induced IRF7 mRNA to “forget” the influence of such initial STAT1Pn temporal behavior.

It has been shown (16) that extension of the IFN pretreatment time beyond 6 h (such as 12 h) leads to a weak DC immune response after virus infection, because the pretreated DCs become resistant to virus infection. Therefore, we would expect an IFN pretreatment of 6 h with a dosage of 50 U/ml to provide a good estimate of the maximum IFN response to virus infection, which was used for the scaling in Fig. 3 A.

In summary, our model predicts two important saturation threshold values for the influence of IFN pretreatment conditions on the enhancement of IFN induction (Fig. 3 A). For a pretreatment >3 h, a low pretreatment dosage of 5 U/ml is enough to provide ∼90% of the maximum enhancement in IFN induction associated with solely increasing IFN dosage. For a fixed pretreatment dosage >5 U/ml, a pretreatment length of ∼3 h is also able to give ∼90% of the maximum in IFN induction.

Simulations for DC in vivo responses to virus infection

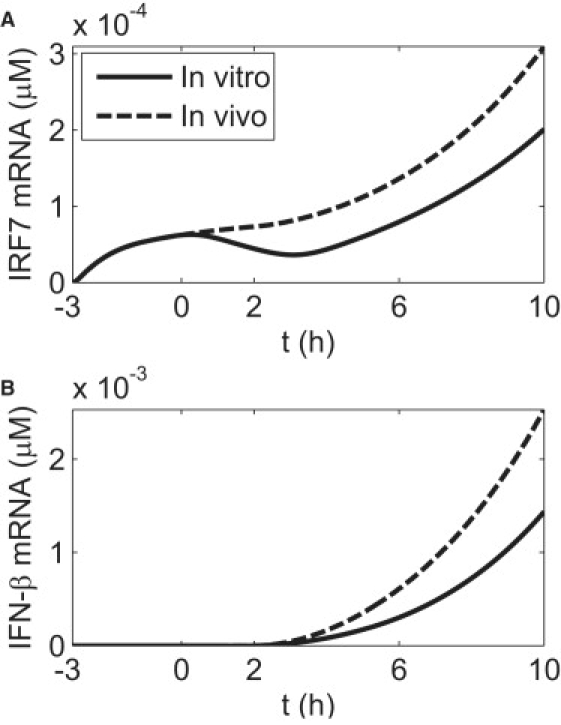

The in vivo environment is different from the in vitro experiments discussed above in at least the following aspects: 1), the priming time of DCs, which is the time the immature uninfected DC is exposed to IFN, varies among cells; 2), the IFN in the tissue is not removed after infection; and 3), the in vivo IFN level at the site of infection is found to vary much more slowly over time when compared to our in vitro experiments (T. Hermesh, B. Moltedo, T. M. Moran, and C. B. Lopez, unpublished). We thus performed simulations with our model to compare IFN responses to virus infection under in vitro IFN pretreatment and in vivo IFN priming conditions. As the in vivo extracellular IFN level increases very slowly, we assumed a constant extracellular IFN level during the 10-h time span of our simulations.

Fig. 4 shows that with the same dosage of priming or pretreatment, the in vivo cellular immune response to viral infection is stronger than that in vitro. The level of in vivo IRF7 mRNA does not diminish for the first 2 h after infection, because its degradation is compensated by induction, due to persistent external IFN. As a consequence, the amount of induced IFN-β increases more sharply after 2 h in vivo than in vitro. The production of other factors, such as cytokines and antiviral proteins, released through the JAK/STAT pathway, can also be expected to be enhanced in vivo. The difference in IRF7 mRNA level during the early stage of viral infection (t = 0–2 h), which strongly influences the early IFN response (starting at t = 2 h) (Fig. 4), could become important in determining the long-term IFN response when the antagonist activity of the influenza virus is taken into account. NS1 is an antagonist viral protein that inhibits the RIG-I signaling pathway (48). A dramatic increase in NS1 mRNA is observed ∼2 h after influenza infection (16), which is also the time when IFN mRNA increases (Fig. 4). Such simultaneous upregulation of NS1 and IFN mRNA implies the existence of two competing processes. On one hand, the NS1 protein inhibits the RIG-I signaling pathway and thus reduces IRF7 activation and IFN induction. On the other hand, extracellular IFN induces the key components of the RIG-I signaling pathway (including RIG-I, Tripartite-motif-containing 25 (41), and IRF7) to avoid the shutdown by NS1. At the same time, it activates several antiviral pathways to inhibit virus replication (8). One would expect that enough IRF7 should be induced and activated during the t = 0–2 h period for the IFN induction feedback loop to win against NS1 inhibition over time, which has been confirmed experimentally (16). Our model predicts that this is more easily achieved in vivo than in vitro.

Figure 4.

Simulations of the temporal IFN response to virus infection under in vitro IFN pretreatment and in vivo IFN priming conditions. (A) The temporal behavior of IRF7 mRNA. (B) The temporal behavior of IFN-β mRNA. Virus infection is introduced at t = 0. For the in vitro case, an IFN pretreatment dosage of 20 U/ml with a pretreatment time of 3 h is used. The concentration of the infected DCs is set to 5 × 105 cells/ml, as in Fig. 2. For the in vivo simulation, a constant extracellular IFN level of 20 U/ml is used, and the priming time is set to 3 h.

We also studied the dependence of in vivo DC IFN response on IFN priming conditions, similar to that for the in vitro case shown in Fig. 2. The results (not shown) are found to be very similar to the in vitro case, and the threshold values of IFN priming dosage and time corresponding to 90% of the maximal IFN response are estimated to be 8 U/ml and 2 h, respectively.

Conclusion

We performed experiments on human DCs to investigate the enhanced immune response to influenza virus infection after IFN-β pretreatment. A comprehensive computational model was developed based on the experimental time course data for proteins and mRNAs that mediate the IFN response. The model describes the dynamics of cellular immune response in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, as well as in the extracellular medium. The results fit the data nicely over a 13-h period that includes 3 h of pretreatment. The dynamics of immune response shows two distinct phases after viral infection: a 2-h phase during which the level of the main regulator IRF7 declines and no IFN induction takes place, and a second phase in which the amount of IRF7 increases due to JAK/STAT pathway activation and IFN induction takes off. This result shows that for pretreated cells, it takes ∼2 h between viral infection and IRF7 induction. Some time courses, in particular that of nuclear STAT1P, show significant variation over the span of the experiment, and provide strong constraints on model parameters. That IRF7 mRNA continues to increase after 6 h, whereas STAT1Pn and SOCS1 level off, imposes another constraint. Since IRF7 mRNA half-life is estimated to be the typical value of 2 h, the continued increase of IRF7 mRNA up to 10 h requires the presence of a previously known autoinduction mechanism that functions after infection alongside the JAK/STAT pathway.

Our model provides insight into the kinetics of IFN induction in pretreated DCs and helps to identify the extracellular IFN level as the key regulator of the overall dynamics. Since IRF7 activation is very fast, it is the amount of IFN in extracellular space that determines the timescale of cellular response to viral infection. Extracellular IFN, which comes from cellular secretion after infection, is part of a positive feedback loop across the cell population. We applied our model to explore the effects of varying IFN pretreatment conditions on IFN induction in IFN-pretreated DCs after virus infection. Two important saturation threshold values emerge concerning dosage and pretreatment time. The result is that IFN induction reaches near saturation for dosages >5 U/ml and durations >3 h. The model is then extended to simulate the in vivo IFN induction of DCs at the site of infection. We found that in the same conditions, IFN mRNA induction occurs at a faster rate in vivo than in vitro, and is determined by the level of IRF7 mRNA present in the cell at the early stages of influenza virus infection. Thus, the cell is better prepared to combat the virus in vivo than under similar conditions in vitro.

As a final note, we raise the usual flags of modeling caution, which arise from the fact that the model describes a limited set of data over a finite temporal range. From inspection of Fig. 2, it is clear that the system of components has not reached steady state at 10 h after infection, since IRF7 and the IFNs continue to increase. This behavior cannot go on indefinitely, even though in the model it would. The reason is that for the sake of keeping the number of parameters small, some of the reactions are described by equations in which only the linear part of a saturating Michaelis-Menten expression is retained (e.g., induction of IFN-α/β mRNA by IRF7Pn). If one were to extend the model beyond 10 h, some of the equations would need to be rewritten, at the price of introducing additional parameters. Moreover, some of the assumptions made to simplify the model would need to be reevaluated if new measurements were to appear. The conclusion is that model methodology—here, the tailoring of model size to the number of experimental measurements—is more important than model details.

Supporting Material

Model of type I IFN induction in IFN-pretreated human DCs, model equations, a table, references, and two figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(09)01723-8.

Supporting Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yishai Shimoni for discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract HHSN266200500021C, and National Institutes of Health grants U19 AI62623 and RO1 AI041111.

References

- 1.Trumpfheller C., Finke J.S., Steinman R.M. Intensified and protective CD4+ T cell immunity in mice with anti-dendritic cell HIV gag fusion antibody vaccine. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:607–617. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J., Steinman R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira S., Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi O., Akira S. MDA5/RIG-I and virus recognition. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myong S., Cui S., Ha T. Cytosolic viral sensor RIG-I is a 5′-triphosphate-dependent translocase on double-stranded RNA. Science. 2009;323:1070–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1168352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stetson D.B., Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 2006;25:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shvartsman S.Y., Hagan M.P., Lauffenburger D.A. Autocrine loops with positive feedback enable context-dependent cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C545–C559. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00260.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadler A.J., Williams B.R.G. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller O., Weber F. Pathogenic viruses: smart manipulators of the interferon system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;316:315–334. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Sastre A., Egorov A., Muster T. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology. 1998;252:324–330. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Sesma A., Marukian S., Moran T.M. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J. Virol. 2006;80:6295–6304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02381-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brimnes M.K., Bonifaz L., Moran T.M. Influenza virus-induced dendritic cell maturation is associated with the induction of strong T cell immunity to a coadministered, normally nonimmunogenic protein. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:133–144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montoya M., Schiavoni G., Tough D.F. Type I interferons produced by dendritic cells promote their phenotypic and functional activation. Blood. 2002;99:3263–3271. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollara G., Jones M., Katz D.R. Herpes simplex virus type-1-induced activation of myeloid dendritic cells: the roles of virus cell interaction and paracrine type I IFN secretion. J. Immunol. 2004;173:4108–4119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osterlund P., Veckman V., Julkunen I. Gene expression and antiviral activity of α/β interferons and interleukin-29 in virus-infected human myeloid dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:9608–9617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9608-9617.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phipps-Yonas H., Seto J., Fernandez-Sesma A. Interferon-β pretreatment of conventional and plasmacytoid human dendritic cells enhances their activation by influenza virus. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000193. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bordería A.V., Hartmann B.M., Sealfon S.C. Antiviral-activated dendritic cells: a paracrine-induced response state. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6872–6881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda K., Yanai H., Taniguchi T. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato M., Hata N., Tanaka N. Positive feedback regulation of type I IFN genes by the IFN-inducible transcription factor IRF-7. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:106–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda K., Yanai H., Taniguchi T. Regulation of the type I IFN induction: a current view. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:1367–1378. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marié I., Durbin J.E., Levy D.E. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-α genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J. 1998;17:6660–6669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S., tenOever B.R., Hiscott J. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science. 2003;300:1148–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.1081315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marié I., Smith E., Levy D.E. Phosphorylation-induced dimerization of interferon regulatory factor 7 unmasks DNA binding and a bipartite transactivation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8803–8814. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8803-8814.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin R.T., Mamane Y., Hiscott J. Multiple regulatory domains control IRF-7 activity in response to virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:34320–34327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato M., Suemori H., Taniguchi T. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-α/β gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Platanias L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada S., Shiono S., Yoshimura A. Control mechanism of JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway. FEBS Lett. 2003;534:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smieja J., Jamaluddin M., Kimmel M. Model-based analysis of interferon-β induced signaling pathway. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2363–2369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell J.E., Kerr I.M., Stark G.R. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ihle J.N., Kerr I.M. Jaks and Stats in signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily. Trends Genet. 1995;11:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stark G.R., Kerr I.M., Schreiber R.D. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung S., Qureshi S.A., Stark G.R. Role of STAT2 in the α interferon signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:1312–1317. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Decker T., Lew D.J., Darnell J.E. Two distinct α-interferon-dependent signal transduction pathways may contribute to activation of transcription of the guanylate-binding protein gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:5147–5153. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frahm T., Hauser H., Köster M. IFN-type-I-mediated signaling is regulated by modulation of STAT2 nuclear export. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1092–1104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ten Hoeve J., de Jesus Ibarra-Sanchez M., Shuai K. Identification of a nuclear Stat1 protein tyrosine phosphatase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5662–5668. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5662-5668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu D., Qu C.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the JAK/STAT pathway. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:4925–4932. doi: 10.2741/3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito H., Morita Y., Kishimoto T. IFN regulatory factor-1-mediated transcriptional activation of mouse STAT-induced STAT inhibitor-1 gene promoter by IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 2000;164:5833–5843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenner J.E., Starr R., Hertzog P.J. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 regulates the immune response to infection by a unique inhibition of type I interferon activity. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:33–39. doi: 10.1038/ni1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoneyama M., Fujita T. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merika M., Thanos D. Enhanceosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001;11:205–208. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakasato N., Ikeda K., Inoue S. A ubiquitin E3 ligase Efp is up-regulated by interferons and conjugated with ISG15. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;351:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ning S.B., Huye L.E., Pagano J.S. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of the IRF7 promoter by a pathway independent of interferon signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12262–12270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Press W.H., Teukolsky S.A., Flannery B.P. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Birtwistle M.R., Hatakeyama M., Kholodenko B.N. Ligand-dependent responses of the ErbB signaling network: experimental and modeling analyses. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:144. doi: 10.1038/msb4100188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung S.W., Miles F.L., Ogunnaike B.A. Quantitative modeling and analysis of the transforming growth factor β signaling pathway. Biophys. J. 2009;96:1733–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siewert E., Müller-Esterl W., Schaper F. Different protein turnover of interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling components. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;265:251–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novák B., Tyson J.J. Design principles of biochemical oscillators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:981–991. doi: 10.1038/nrm2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mibayashi M., Martínez-Sobrido L., García-Sastre A. Inhibition of retinoic acid-inducible gene I-mediated induction of β interferon by the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 2007;81:514–524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.