Abstract

Whether α6β4 integrin regulates migration remains controversial. β4 integrin-deficient (JEB) keratinocytes display aberrant migration in that they move in circles, a behavior that mirrors the circular arrays of laminin (LM)-332 in their matrix. In contrast, wild-type keratinocytes and JEB keratinocytes, induced to express β4 integrin, assemble laminin-332 in linear tracks over which they migrate. Moreover, laminin-332-dependent migration of JEB keratinocytes along linear tracks is restored when cells are plated on wild-type keratinocyte matrix, whereas wild-type keratinocytes show rotation over circular arrays of laminn-332 in JEB keratinocyte matrix. The activities of Rac1 and the actin cytoskeleton-severing protein cofilin are low in JEB keratinocytes compared with wild-type cells but are rescued following expression of wild-type β4 integrin in JEB cells. Additionally, in wild-type keratinocytes Rac1 is complexed with α6β4 integrin. Moreover, Rac1 or cofilin inactivation induces wild-type keratinocytes to move in circles over rings of laminin-332 in their matrix. Together these data indicate that laminin-332 matrix organization is determined by the α6β4 integrin/actin cytoskeleton via Rac1/cofilin signaling. Furthermore, our results imply that the organizational state of laminin-332 is a key determinant of the motility behavior of keratinocytes, an essential element of skin wound healing and the successful invasion of epidermal-derived tumor cells.

Migration of cells is an essential element of morphogenesis, remodeling following tissue damage and metastasis. For example, following wounding of the skin, epidermal cells migrate over a wound, a complex process involving changes in cytoskeleton organization, alterations in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, and modulation in gene and protein expression (1, 2). In particular, keratinocytes lose stable matrix adhesive structures called hemidesmosomes, migrate over exposed dermal collagen, and deposit a provisional matrix rich in laminin (LM)3-332 (old nomenclature: laminin-5), a heterotrimer consisting of α3, β3, and γ2 subunits (1–5). This provisional matrix regulates the motility of keratinocytes (2–4). LM-332 is also believed to support tumor cell invasion (6–12).

Although cells in wounds and cancer cells migrate on a LM-332 substrate, LM-332 stabilizes epidermal cell adhesion in intact skin (3, 4, 12–16). These contradictory functions exhibited by LM-332, adhesion and motility, have been investigated by a number of laboratories, and results to date indicate that proteolytic processing of LM-332 has a profound impact on its functions. Specifically, in the extracellular matrix, the α3 and γ2 subunits are processed from 190 to 160 kDa and from 140 to 100 kDa, respectively (4, 17–22). LM-332 containing an unprocessed α3 chain supports keratinocyte motility (20). Upon proteolytic cleavage of the α3 LM subunit within its G domain, LM-332 triggers hemidesmosome assembly, leading to decreased cell motility (3, 20–24). However, further proteolysis of laminin-332 within its γ2 chain produces a laminin protein and/or fragment that induces cell migration (22, 25, 26).

Two integrin receptors (α3β1 and α6β4) bind LM-332. α3β1 integrin is involved in cell adhesion to LM-332 ligand, LM-332 matrix assembly, and cell motility (3, 4, 16, 27, 28). α6β4 integrin mediates stable adhesion to LM-332 by nucleating assembly of hemidesmosomes (13, 29, 30). In addition, like α3β1 integrin, α6β4 integrin may support cell migration on laminin, although this aspect of α6β4 integrin biology is controversial (13, 29–34). Indeed, several groups have hypothesized that migration of keratinocytes on LM-332 is mediated by α3β1 rather than α6β4 integrin, with the latter having a “transdominating” inhibitory effect on α3β1 integrin (35–38). If this hypothesis is correct, then one might assume that, when β4 integrin is absent, cells should migrate constitutively in a α3β1 integrin-dependent manner. However, here, contrary to this hypothesis, we present evidence showing that cells deficient in β4 integrin have a motility defect. This defect is corrected following re-expression of a wild-type β4 integrin subunit. Our data also indicate that α6β4 integrin, through interaction with the Rac1 signaling pathway, regulates LM-332 matrix organization which, in turn, specifies patterns of cell motility.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Drug Treatments, Matrix Preparation, SDS-PAGE, Immunoblotting, and Immunoprecipitation

Human epidermal (WT) keratinocytes were a gift from Dr. Lou Laimins of Northwestern University. The β4-deficient keratinocytes, derived from a JEB patient, were described previously (Russell et al. (36)). Both lines were immortalized in identical fashion using human papilloma virus E6 and E7 genes (39). They were maintained at 37 °C in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen). The Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 was obtained from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI, National Institutes of Health. It was added to keratinocyte growth medium at 50 μM 24 h prior to cell analysis. Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) was added to growth medium at a concentration of 50 μM.

Keratinocyte matrix was prepared as described previously (40). For immunoprecipitations, keratinocytes were extracted in 1% Brij 97, 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Al-drich Co.). The extract was clarified by centrifugation, and either primary antibody or control IgG was added. After shaking for 4 h at 4 °C, rProtein G-agarose beads (Invitrogen) were added to the mix, which was incubated for 90 min at 4 °C. The beads were washed, collected by centrifugation, and then incubated in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Protein preparations were processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as detailed elsewhere (30). Immunoblots were scanned and quantified using a MetaMorph Imaging System (Universal Imaging Corp., Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA).

Retroviral and Adenoviral Constructs and Infection of Keratinocytes

The wild-type β4 integrin cDNA or a mutant, laminin-332 binding-deficient β4 integrin bearing a mutation in the specificity determining loop (K150A) were described previously (41). Both were fused with sequences encoding GFP at their 3′ ends, cloned into the LNCX2 vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), and sequenced using ABI Big Dye chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The subsequent constructs were introduced into PT67 packaging cells using calcium phosphate-mediated transfection. Briefly, 10 μg of DNA was diluted in 440 μl of sterile water, mixed with 500 μl of 2× HBS (280 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 12 mM dextrose, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.05) and 60 μl 2 M CaCl2, and added dropwise to cells in medium containing 25 μM chloroquine. Following overnight incubation, the medium was removed, cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, and fresh medium was added. The following day, cells were trypsinized and replated into medium (without penicillin/streptomycin) supplemented with G418 (Invitrogen). Surviving cells were subsequently cloned to produce stable cell lines. Four days prior to infecting keratinocytes, PT67 cell lines expressing the β4 integrin construct were transfected with a plasmid encoding the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein using the protocol described above. The following day, the medium was replaced, and the cells were switched to 32 °C for 2 days. The supernatant was harvested and filtered, and 8 μg/ml Polybrene was added. Keratinocytes were incubated in the viral supernatant in plates which were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 2 h at room temperature (42). After removal of viral supernatant, cells were subcultured for subsequent analyses.

Keratinocytes were infected with adenoviruses containing the cytomegalovirus promoter (courtesy of Dr. Kathy Rundell, Northwestern University), the N19 DN mutant of RhoA, the N17 DN mutant of Rac1, the N17 dominant-negative mutant of Cdc42, the V12 CA Rac1 mutant (all c-Myc epitope-tagged, courtesy of Dr. Anne Ridley of University College, London, UK), XAC1 GFP S3E (inactive, phospho-mimetic) cofilin, XAC1 GFP S3A (active, non-phosphorylatable) cofilin (generously provided by Dr. James Bamburg of the University of Colorado at Boulder, CO), and the YFP-tagged β3 laminin subunit at a multiplicity of infection of 1:50 in keratinocyte medium (43). To generate virus encoding YFP-tagged full-length β3 laminin, β3 laminin cDNA was cloned into the pEYFP-N vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) at the BamHI/XhoI sites in the polylinker 5′ to the start of sequences encoding the YFP tag. This produces a fusion protein consisting of the β3 laminin subunit, a spacer of 21 amino acid residues (RAQASNSAVDGTAGPGSPVAT), and YFP. This entire cassette was subcloned into the pENTR-4 vector (Invitrogen). This entry vector was used in a site-directed recombination reaction to place the cassette into the pAD/CMV.V-5-DEST vector following the manufacturer’s directions (Invitrogen). The adenoviral vector was linearized with PacI and transfected into 293A cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Approximately 12 days post transfection, the adenovirus-containing 293A cells were harvested and lysed to prepare a crude viral stock. The resultant viral stock was amplified and titered. Keratinocytes were incubated in virus at 37 °C overnight, and the virus-containing medium was removed. The cells were then fed with fresh medium, followed by incubation at 37 °C. After 18 h, cells were trypsinized and processed for motility assays. To confirm expression of the above constructs, immunoblotting of cell extracts was performed using GFP antibodies or antibody 9E10 against the c-Myc epitope, and/or cultures were viewed by fluorescence microscopy to identify cells expressing GFP- or YFP-tagged protein (not shown). Greater than 80% infection rates were obtained in each of our studies.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against β4 integrin (3E1), α3 integrin (P1B5), β1 integrin antibody (6S6), the α5 laminin subunit (4C7), the β3 laminin subunit (Clone 17), and Rac1 were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA); P1B5 and 6S6 are both inhibitory antibodies. GoH3, a rat monoclonal against α6 integrin, was obtained from Beckman Coulter (Miami, FL). Antibodies against the α3 laminin (RG13) and the γ2 laminin (3D5) subunits were characterized previously (20, 44); RG13 has been shown to be a laminin-332 antagonist (44). A rabbit anti-serum against human fibronectin was purchased from Collaborative Research Inc. (Bedford, MA). 9E10, a mouse monoclonal antibody against the Myc epitope, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). A mix of mouse monoclonal antibodies (clones 7.1 and 13.1) against GFP and its variants, including YFP, was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Antibodies to phospho-cofilin (Ser3) and total cofilin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). A rabbit polyclonal antibody (AA6A) against α6 integrin was generously provided by Dr. Anne Cress (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against β1 integrin was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies conjugated with various fluorochromes or horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA).

For flow cytometry, freshly trypsinized cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing a 50% dilution of normal goat serum, incubated with monoclonal antibodies against α3, β4, or α6 integrin for 45 min at room temperature, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, incubated with Cy5-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 45 min, washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and analyzed using a Beckman Coulter Elite PCS sorter (Beckman Coulter). For negative controls, primary antibody was omitted from the above procedure.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells on glass coverslips were processed as detailed elsewhere (30). All preparations were viewed with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Images were exported as TIFF files, and figures were generated using Adobe Photoshop software.

Observations of Live Cells, Motility Assays, and TIRF

Scratch assays of confluent cell monolayers were performed in triplicate as described elsewhere (3). For studies on the motility of individual and groups of cells, cells were plated onto uncoated or matrix-coated 35 mm glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek Corp., Ash-land, MA). For function-blocking assays, fresh medium containing 20 μg/ml antibody or immunoglobulin was added 15 min prior to visualization. Cells were viewed on a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY) or the Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. Images were taken at 2- to 5-min intervals over a 2-h period, and cell motility was analyzed by MetaMorph (Molecular Devices Corp.). Motility assays were performed a minimum of three times with at least 50 cells being counted in each trial. Wide-field and TIRF observations of live cells were performed on a TIRFM microscope (Olympus America Corp., Melville, NY).

RESULTS

Expression of β4 Integrin in JEB and WT Keratinocytes

We have used keratinocytes derived from a patient with junctional epidermolysis bullosa-pyloric atresia (JEB), a blistering skin disease whose pathogenesis results from an absence of β4 integrin expression (45). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses confirmed that these JEB cells are deficient in β4 integrin (Fig. 1A), but express α3 and α6 integrin at levels comparable to those of wild-type (WT) cells (Fig. 1A). The JEB keratinocytes were infected with retrovirus encoding either GFP-tagged wild-type β4 integrin or β4 integrin bearing a mutation (K150A) that inhibits α6β4 integrin interaction with LM-332 ligand (41). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses reveal that surface expression of β4 integrin protein in these cells (JEBβ4 and JEBβ4Mut) is at levels slightly higher than their WT counterparts; surface expression of α3 and α6 integrin in the cells was comparable to JEB and WT cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, when viewed either by confocal or total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, tagged β4 integrin protein localized along the substratum-attached surface of JEBβ4 and JEBβ4Mut cells in patterns identical to the distribution of endogenous β4 integrin in WT cells (Fig. 1B). JEB cells showed no staining when processed for confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using a β4 integrin antibody probe (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1. Analyses of integrin expression in WT, JEB, JEBβ4, and JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes.

A, cell-surface expression of β4 integrin, α3 integrin, and α6 integrin was compared in WT, JEB, JEBβ4, or JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes (black, secondary antibody alone). In B: i and ii, expression of GFP-tagged β4 integrin was viewed in the same live JEBβ4 cell using wide-field fluorescence microscopy and TIRF optics, respectively. iii, a WT keratinocyte, prepared for indirect immunofluorescence using 3E1 antibodies against β4 integrin, was viewed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. iv, a JEBβ4Mut keratinocyte was viewed by TIRF optics. v and vi, a JEB cell, prepared for immunofluorescence using 3E1 antibody, was viewed by phase contrast (v) and by confocal microscopy (vi). iii and vi, the focal plane was close to the substratum-attached surface of the cell. Bar, 10 μm.

JEB Cells Exhibit Aberrant Motility Behavior

We next assayed the migration of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, and JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes in scratch wound motility assays (Fig. 2). Consistent with others (36), both JEB and JEBβ4Mut cell populations displayed delayed wound closure compared with WT and JEBβ4 keratinocytes (Fig. 2). We have also monitored migration of individual and groups of cells following plating onto an uncoated substrate. These assays were performed at 6–8 h after plating to allow the cells to adhere and spread. JEB and JEBβ4Mut cells showed significantly lower overall migration and displacement over a 2-h period than their WT counterparts (Fig. 3A). These deficiencies were not observed in JEBβ4 cells, which exhibit migration similar to WT cells (Fig. 3A). We also calculated the directed migration index (net displacement divided by total distance traveled) for the four cell types. None of the indices approached one indicating that the four keratinocytes failed to exhibit directed/processive migration under these conditions (Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, upon careful examination of the images we derived, we noticed that our cells show two distinct motile behaviors. WT cells move along linear tracks (Fig. 3, B (panel i) and C, and supplemental video 1). In addition, a number of WT cells change trajectory and move back over the same regions of the substrate that they have already traversed (backtracking is exhibited by 34 (±3) % of WT cells that we have examined; n = 163, in three trials), which is the clear reason why they do not exhibit directed migration. In contrast, JEB cells move primarily in circles and exhibit little or no migration along linear tracks; this is true of individual cells as well as groups of adherent cells (Fig. 3, B (panels ii and iii) and C, and supplemental video 2). The migratory patterns displayed by the JEB cells explain why these cells failed to close a wound in a scratch assay (Fig. 2) (36). The motility of JEBβ4 keratinocytes is similar to WT cells (Fig. 3, B (panel iv) and C, and supplemental video 3), whereas JEBβ4Mut cells showed migration patterns comparable to JEB cells (Fig. 3, B (panel v) and C, and supplemental video 3).

FIGURE 2. Scratch wound motility assays.

Confluent monolayers of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, or JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes were scratched, fed with fresh medium, and photographed. After 48 h the cultures were photographed again, and the percent change in wound width was measured (mean ± S.D. for three independent trials); **, p < 0.01, indicate a significant difference when comparing JEB, JEBβ4, or JEBβ4Mut with WT keratinocytes (t test). NS, not significant.

FIGURE 3. Motility assays of keratinocytes on uncoated glass.

A, motility of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, or JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes was evaluated at 6 – 8 h following plating of cells onto glass coverslips by phase-contrast microscopy for 2 h. The three graphs, from left to right, indicate the total distance moved by the cells, net displacement, and directed migration index, respectively (mean ± S.D.; n ≥ 3 trials involving at least 50 cells per trial); *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01; indicate a significant difference from WT (t test). In B: i–v, examples of motility behavior of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, or JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes, as observed by phase-contrast microscopy at the indicated time points, are shown. Of the two WT cells in i, one cell migrates out of the field of view, while the other, which initially is at the bottom of the panel, moves to the upper left corner. JEB cells, including a cluster of three cells, undergo circular motion in ii. This circular motion is also exhibited by the single JEB cell in iii. In iv, two JEBβ4 cells move independently from the upper right to the lower left corner of the panels, whereas in v a JEBβ4Mut keratinocyte moves in a circle. In vi, JEB keratinocytes were evaluated as above, except α3 integrin function-inhibitory antibody P1B5 (20 μg/ml) was added 30 min prior to visualization. Phase images are shown at the same magnification. The bar in phase images, 10 μm. In C, representative tracks of six to eight randomly chosen cells from three trials involving a minimum of 50 cells per trial are shown. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken as the starting point of each cell path.

The motility of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, and JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes is inhibited by removal of growth factors (not shown) or by α3 and β1 integrin antagonists (P1B5 and 6S6, respectively, only results using P1B5 are shown; Fig. 3B (panel vi)). The antagonists were added to the cells at 6 h after plating, at a time when the cells have adhered to substrate and assembled an LM-332 matrix (not shown). Our analyses were begun 30 min later. The treated cells appeared to “wobble” but showed no obvious motility (Fig. 3B (panel vi)). Control immunoglobulins had no apparent effect on migration (not shown). These results indicate that the motility of all of our assayed keratinocytes is likely growth factor- and α3β1 integrin-regulated, consistent with previous studies (16, 36).

Laminin-332 Matrix Organization Regulates Keratinocyte Motility Behavior

The aberrant motility of JEB cells detailed above might reflect an inherent migration machinery defect in the cells. To assess this possibility, we compared the motility of JEB and WT cells after plating on WT cell matrix. We also compared the migration of JEB and WT cells on JEB cell matrix. Our analyses were performed at 2 h after plating, because the cells rapidly adhere to and spread on the preformed matrices, and we wished to minimize the possibility that the cells would modify the matrix upon which they were plated. JEB keratinocytes and WT cells on the matrix of WT cells exhibited comparable levels of overall distance moved and directed migration; however, JEB cells exhibited somewhat lower displacement values than WT cells, following plating on WT matrix (Fig. 4A). In addition, WT cells and JEB cells both displayed comparable levels of overall migration and displacement on the matrix of JEB cells, albeit at levels lower than that when they were plated onto WT cell matrix (Fig. 4A). Moreover, even on preformed matrices, both WT and JEB cells failed to exhibit directed migration. More important, however, the majority of JEB and WT cells showed movement along linear tracks when plated onto the matrix of WT cells (Fig. 4, B (panel i) and C), whereas WT and JEB keratinocytes moved in a relatively circular fashion on the matrix of JEB cells (Fig. 4, B (panel ii) and C). To rule out the possibility that the cells secrete matrix components and/or proteases that change the functional properties of the matrix, keratinocytes were treated with Brefeldin A (supplemental Fig. S1A). Treatment had no impact on the motile behaviors of the cells, regardless of the matrix on which they were plated. In summary, these data imply: 1) that the intrinsic motile machinery of JEB cells is functional and 2) that the matrix of keratinocytes regulates the precise motile behavior of adherent keratinocytes.

FIGURE 4. Motility assays of keratinocytes on organized arrays of LM-332.

A, motility of WT and JEB cells was monitored for 2 h by phase-contrast microscopy, 2 h after plating cells onto the LM-332-rich matrix deposited by either WT or JEB cells. The three graphs, from left to right, indicate total distance moved by the cells, net displacement, and directed migration index, respectively (mean ± S.D.; n ≥ 3). *, p < 0.01, indicate a significant difference between bracketed results (t test) (n ≥ 3 trials involving at least 50 cells per trial). NS, not significant. B, representative examples of phase images of JEB cells migrating on the matrix of WT cells (i), WT cells migrating on the matrix of JEB cells (ii), and JEB cells migrating on the matrix of WT cells in the presence of either the antibody RG13 against the α3 LM subunit (iii) or P1B5 against the α3 integrin subunit (iv). The antibodies (20 μg/ml) were added 30 min prior to visualization. Bars: in i and ii, 10 μm; in iii and iv, 50 μm. In C, representative tracks of 8 –14 randomly chosen cells from three trials involving a minimum of 50 cells per trial are shown. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken as the starting point of each cell path.

The matrices of WT and JEB cells were both enriched in LM-332, whose subunit composition was comparable (supplemental Fig. S2). To determine whether LM-332 is the functionally active component of the matrix in supporting migration behavior, keratinocytes were allowed to adhere and spread on matrix for 2 h, and then the α3 LM subunit antagonist antibody RG13 was added to the cells (44). After a 30-min incubation, analyses of migration of the cells were begun. RG13 antibody inhibited migration of JEB cells on WT cell matrix and vice versa (only results for JEB cells on WT cell matrix are shown; Fig. 4 (B (panel iii) and C) (control immunoglobulin had no impact; not shown). Similarly, the α3 integrin antagonist P1B5 inhibited the motility of JEB and WT cells plated onto each other’s matrix (Fig. 4, B (panel iv) and C). These results indicate that motile behavior of the cells, irrespective of matrix type, its processing, or components, is LM-332- and α3 integrin-dependent.

If motility of keratinocytes on both JEB and WT cell matrix is LM-332-dependent, does LM-322 organization determine the differences in motile behaviors exhibited by JEB versus WT keratinocytes? WT keratinocytes secreted LM-332 primarily as linear tracks that appeared for some distance beyond the cells (Fig. 5i). Moreover, live cell imaging of WT keratinocytes, which have been induced to express a YFP-tagged β3 LM subunit via adenoviral delivery (the YFP is at the C-terminal end of the molecule), revealed that the cells move along these labeled, linear LM-332-rich tracks (Fig. 6i; in the example shown the cells undergo the backtracking behavior mentioned earlier; supplemental video 4). In these studies, there was a 42:58 ratio of tagged to untagged β3 laminin subunits in the matrix of the cells (supplemental Fig. S3). Moreover, the YFP tag provided an accurate representation of the secreted and assembled laminin-332 matrix, because it showed precise colocalization with the γ2 subunit when the matrix was stained by GB3 antibody (not shown).

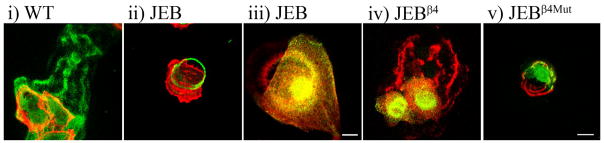

FIGURE 5. LM-332 organization in the matrix of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, and JEBβ4Mut keratinocytes.

Cultures of WT (i), JEB (ii and iii), JEBβ4 (iv), and JEBβ4Mut (v) keratinocytes were prepared for confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies against LM-332 (green in i and ii and red in iii–v). The WT cells in i and JEB cells in ii were double-labeled with rhodamine phalloidin (red); the JEB cells in iii were processed with α3 integrin antibody (green); in iv and v, green represents GFP-tagged wild-type and mutant β4 integrin, respectively. Bars: in iii, 12.5 μm; in v, 25 μm.

FIGURE 6. Live cell imaging studies on labeled LM-332 matrices.

WT (i) and JEB (ii) cells expressing a YFP-tagged β3 LM subunit were plated onto glass coverslips and visualized 8 h later. In iii and iv, JEB or WT cells were plated onto the labeled matrix assembled by JEB or WT cells as indicated. 2 h after plating the motility of the cells was monitored. Phase/fluorescence overlays at the indicated time points, are shown. In iii, a WT cell migrates in a circle pattern delineated by LM-332 in the matrix assembled by JEB cells. In iv, a series of images of a JEB cell moving over the matrix assembled by WT cells is shown. Bar, 50 μm.

JEB cells assembled LM-332 in intersecting arcs/circles with which the α3 integrin subunit colocalized (Fig. 5, ii and iii). The α6 integrin-blocking antibody, GoH3, when added to the medium of the cells prior to plating onto uncoated coverslips, did not inhibit assembly of the LM-332 circles, indicating that their formation is not α6 integrin-dependent (not shown). Furthermore, JEB cells, expressing a YFP-tagged β3 LM subunit, move over the labeled circular arrays of LM-332 that they secrete (Fig. 6ii and supplemental video 4). The distinct organizational states of the proteins in the matrix of both WT and JEB cells appear specific for LM-332; we have observed no obvious LM-10/11 staining, and only diffuse fibronectin staining, in WT and JEB cell matrix (not shown).

The above results imply that LM-332 organization in the matrix of keratinocytes not only mirrors the motile behaviors of adherent cells but also specifies keratinocyte motile behavior patterns. To provide further support for this, we assayed migration of WT cells at 2 h after plating onto YFP-labeled LM-332-rich arrays of JEB cell matrix and vice versa. In both instances, cells migrated precisely along the tracks or circles defined by the preformed arrays of LM-332 (Fig. 6 (panels iii and iv) and supplemental video 5).

The morphologically distinct arrangement of LM-332 in the matrix of JEB versus WT cells suggested the possibility that β4 integrin may be involved in determining LM-332 organization. To assess if this is the case, we assayed LM-332 organization in JEBβ4 cells. JEBβ4 keratinocytes assembled a matrix in which LM-332 was organized into linear patterns rather than circles (Fig. 5iv). JEBβ4Mut cells, expressing a ligand-binding defective β4 integrin, assembled a LM-332 matrix organized into circles (Fig. 5v).

Motile Behavior of Keratinocytes and Their Matrix Organization Are Dependent on Active Rac1

The small GTPases of the Rho family regulate assembly of fibronectin and LM matrices (46–48). In this regard, previous analyses indicate that the activity of the small GTPase Rac1 is significantly lower in JEB cells than in WT cells and that Rac1 activity is regulated by α6β4 integrin (35–38). Based on these results, we evaluated whether Rac1 is involved in determining motile behavior of keratinocytes via effects on LM-332 matrix organization. To do so, we expressed dominant-negative (DN) Rac1 as well as DN versions of two other small GTPases (cdc42 or RhoA) in WT cells. Expression of the mutant proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 7A), and motility assays were performed on the cells. WT cells expressing either DN cdc42 or DN Rac1 exhibited motility defects (Fig. 7, B (panels i–iii) and C, and supplemental video 6). Most of the cells in the former instance appeared to wobble in place, although an occasional cell showed circular motion (Fig. 7, B (panel i) and C). In contrast, cells expressing DN Rac1 exhibited the same circular migration patterns that are shown by JEB cells (Fig. 7, B (panels ii and iii) and C, and supplemental video 5). The same was true when WT cells were treated with the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (49, 50) (Fig. 7, B (panel iv) and C). DN RhoA had little or no effect on the motility behavior of WT cells (Fig. 7C). WT keratinocytes expressing DN Rac1 or WT cells treated with an Rac1 inhibitor also assembled circles of LM-332 (Fig. 7D, panels i and ii). In addition, untreated WT cells move in a circular fashion on the matrix assembled by WT cells in which the activity of Rac1 has been inhibited (supplemental Fig. S1B). Because the converse is also true (WT cells expressing DN Rac1 move in linear tracks on the matrix of untreated WT cells (supplemental Fig. S1B)), this implies that Rac1 regulates keratinocyte motility behavior by determining LM-332 matrix organization rather than negatively impacting the internal motile machinery of the cells. However, expression of constitutively active (CA) Rac1 is incapable of rescuing the motility defects of JEB cells, and it does not induce the cells to assemble linear tracks of LM-332 (Fig. 7A; not shown).

FIGURE 7. Motility assays of WT keratinocytes expressing mutants of various small GTPases.

A, extracts of WT keratinocytes expressing c-Myc-tagged DN Rac1, DN RhoA, or DN Cdc42, and JEB cells expressing the c-Myc-tagged CA Rac1 were processed for SDS-PAGE/Western blotting using a c-Myc antibody. The bar indicates 22-kDa molecular mass marker. B, motility of WT keratinocytes expressing DN cdc42 (i), DN Rac1 (ii and iii), and WT cells treated with the Rac1 inhibitor (NSC23766) was evaluated 6 – 8 h after plating for up to 2 h by phase-contrast microscopy. Bars: in i, ii, and iv, 20 μm; in iii, 10 μm. In C, representative tracks of 7–10 randomly chosen cells from three trials involving a minimum of 50 cells per trial are shown. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken as the starting point of each cell path. In D, WT keratinocytes expressing DN Rac1 or treated with the Rac1 chemical inhibitor were prepared for confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies against LM-332 (green). In i, the two cells were double labeled with rhodamine phalloidin (red), whereas the cell in ii is shown by phase-contrast microscopy. The focal plane is as close as possible to the substratum-attached surface of the cell. Bars in D, 20 μm.

To provide additional evidence of a link between Rac1 signaling and α6β4 integrin-regulated matrix assembly and motility, we assessed whether Rac1 complexes with β4 integrin in sub-confluent, motile WT keratinocytes. Indeed, Rac1 co-precipitates with α6β4 integrin (Fig. 8). In contrast, α3 integrin antibodies fail to co-precipitate significant levels of Rac1 from keratinocyte extracts, although they co-precipitate β1 integrin (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8. Rac1 co-precipitates with α6β4 integrin.

Extracts of WT cells were processed for immunoprecipitation using either a β4 integrin monoclonal antibody, control IgG (−), or an α3 integrin monoclonal antibody. The precipitated proteins were subjected to immunoblotting using Rac1, β1 integrin, or α6 integrin antibodies as indicated.

Cofilin Regulates the Motile Behavior of Keratinocytes and Their Matrix Organization

The actin-severing protein cofilin is involved in regulating actin organization and, as a downstream target of Rho GTPases, is a key regulator of migration (51–54). The relative level of Ser3 phosphorylated (inactive) cofilin in JEB cells was greater than in uninfected WT cells, JEBβ4 cells, or WT cells expressing DN RhoA or DN cdc42 (Fig. 9A). However, the level of inactive cofilin in JEB cells was comparable to that in WT cells expressing DN Rac1 and in WT cells treated with the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (Fig. 9A), indicating that cofilin activity is linked to the distinct motile behavior of our keratinocytes lines. We have confirmed this, because WT cells induced to express a dominant-inactive, phospho-mimetic cofilin mutant via adenoviral infection show the same motility phenotype as JEB cells (Fig. 9, B and C, and supplemental video 6) (43). The infected cells assemble circular arrays of LM-332 in their matrix (Fig. 9D). In addition, WT cells move in a circular fashion on the matrix laid down by WT cells in which the activity of cofilin has been inhibited (supplemental Fig. S1C). The relative activity level of cofilin in JEBβ4Mut cells is comparable to that of WT cells even though the former showed an aberrant circular migration behavior (Figs. 3B (panel v) and 9A). This suggests that the mutant β4 integrin is capable of triggering certain signaling pathways, but its inability to bind ligand precludes assembly of LM-332 into linear tracks. Moreover, expression of CA Rac1 in JEB cells also results in an increase in active cofilin without rescuing the motility phenotype of the cells (Fig. 9). Similarly, JEB cells induced to express a dominant-active, non-phosphorylatable cofilin mutant exhibit the same circular migration behavior and matrix organization of their non-infected counterparts (43) (not shown). These data imply that the activity of cofilin is positively regulated by Rac1 and that active cofilin is necessary but not sufficient to induce LM-332 assembly into an organization that supports migration of keratinocytes along linear tracks (55).

FIGURE 9. Cofilin activity in JEB and WT keratinocytes and effects of expression of dominant-inactive cofilin in WT cells.

A, whole cells extracts of WT, JEB, JEBβ4, WT cells expressing DN Rac1, WT cells treated with the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766, WT cells expressing DN RhoA, WT cells expressing DN cdc42, and JEB expressing CA Rac1 were processed for SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting. Blots were probed first with antibodies against phosphorylated cofilin (pSer3) and then with antibodies against total cofilin. The percent phosphorylation was calculated relative to total cofilin levels in each of three studies, and the quantification is shown. Error bars indicate ± S.D. B, motility of WT keratinocytes expressing GFP-tagged dominant-inactive cofilin was evaluated for 90 min by phase-contrast microscopy at 8 h after plating. Bar, 20 μm. In C, representative tracks of 8 randomly chosen cells from 3 trials involving a minimum of 50 cells per trial are shown. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken as the starting point of each cell path. In D, WT cells expressing dominant-inactive cofilin were prepared for immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies against LM-332 (red). Green indicates expression of the tagged mutant cofilin. The focal plane is close to the substratum-attached surface of the cell. Bar, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

Most studies on LM-332 have focused on its receptor-binding motifs, its role in disease, and the functions of its fragments (3, 4, 20, 24–26, 56). Many of these studies have assayed cell behavior on LM-332 randomly spread onto surfaces. Our data reveal that there is an added complexity. The organizational state of LM-332 specifies cellular migration patterns. JEB cell migration is restricted to circular arrays of LM-332. Likewise, WT keratinocytes show LM-332-dependent migration and move along linear tracks of LM-332. Our data provide evidence that this is independent of LM-332 subunit processing and whatever accessory proteins reside in the matrix, because an LM-332 antagonist blocks migration of keratinocytes on both WT and JEB cell matrix.

Although there is circumstantial evidence that β4 integrin regulates cell motility (31–33), a recent report has presented data that spontaneously immortalized mouse keratinocytes lacking β4 integrin show enhanced, rather than defective, migration (57). The latter result has led Raymond and coworkers (57) to conclude that α6β4 integrin functions to “impede” cell migration. In contrast, our data indicate that immortalized, β4 integrin-deficient, human keratinocytes lack the ability to move in a linear fashion and migrate primarily in circles. It remains unclear why our results diverge from those of Raymond et al. (57), although the divergent results may reflect differences between spontaneous versus viral-immortalized cells. Regardless of any discrepancies, the mutant motility phenotype of JEB cells is corrected following expression of wild-type β4 integrin. This finding directly pinpoints α6β4 integrin as an active participant in keratinocyte motility. Furthermore, our data are consistent with reports linking α6β4 integrin to regulation of motility (32–34).

There is only one report that α6β4 integrin plays a role in matrix assembly (58); most studies have focused on how β1 integrin is required for LM matrix assembly (see, for example, Refs. 59 – 61). Indeed, our own previous studies have pointed to a crucial role for the α3 integrin subunit in LM-332 matrix assembly, because cells lacking α3(β1) integrin assemble aberrant arrays of LM-332 (28). Thus, one possible explanation for our results is that α6β4 integrin indirectly determines LM-332 matrix organization via its influence on α3β1 integrin. Although we cannot rule out this scenario, we believe it is unlikely. It implies that α6β4 integrin positively regulates the functions of α3β1 integrin, whereas it is widely accepted that the reverse is the case (35–38). Moreover, β4 integrin must be capable of binding LM-332 ligand in order for LM-332 matrix to be properly organized implying that α6β4 integrin is actively organizing LM-332 matrix. Indeed, based on our previous data and the results we have presented here, we propose that the LM-332 matrix of keratinocytes assembles in “two phases.” Specifically, LM-332 is first organized into circles in the extracellular matrix in an α3 integrin-dependent manner (28). We hypothesize that α6β4 integrin may remodel circular arrays of LM-332 into linear tracks. Cells deficient in β4 integrin retain LM-332 in circular arrays and show α3β1 integrin-dependent circular motility. Consistent with this hypothesis, α3 integrin co-localizes with LM-332 in JEB cells. Moreover, our previous data (28) suggest that, in the absence of α3 integrin, and therefore without the initial, α3 integrin-dependent phase of LM-332 organization, LM-332 is aberrantly arranged into arrowhead arrays. We propose that an initial, α3 integrin-dependent phase of LM-332 organization is a necessary prerequisite for the β4 integrin-mediated arrangement of LM-332 into linear tracks along which keratinocytes move in a α3 integrin-dependent manner.

We also report that assembly of LM-332 matrix into linear arrays depends on Rac1. Rac1 co-precipitates robustly with α6β4 integrin from extracts of migrating keratinocytes, suggesting that α6β4 integrin/Rac1 complexes are central to the mechanism via which α6β4 integrin regulates LM-332 matrix organization. One might explain this by proposing that β4 integrin signals through Rac1 and indirectly regulates matrix assembly. However, this would be inconsistent with our finding that constitutively active Rac1 fails to rescue the motility defect of JEB cells and that a ligand-binding defective β4 integrin is capable of activating Rac1-regulated pathways but does not induce LM-332 assembly into linear tracks. These data indicate that Rac1 activation is necessary but not sufficient for LM-332 to be assembled into linear arrays.

How does Rac1 regulate matrix assembly and, in so doing, keratinocyte motility behavior? Rac1 does so via its impact on the actin-severing protein cofilin. We suggest that β4 integrin interacts with and activates Rac1, which then induces activation of cofilin. This would parallel Rac1-mediated cofilin activation by epidermal growth factor-related growth factors in MCF-7 epithelial cells (55) (Fig. 10). Our data support this in that cofilin activity is down-regulated in WT keratinocytes where Rac activity is inhibited but not when the cells are expressing DN RhoA or cdc42 or in cells expressing CA Rac1. The mechanism we propose is distinct from a pathway via which active Rac1 induces an inactivation of cofilin through LIM kinase 1 (62–64).

FIGURE 10.

Model depicting the way β4 integrin, through Rac1 and the actin cytoskeleton, regulates the organizational state of LM-332 in the extracellular matrix.

The involvement of Rac1 and cofilin in regulating LM-332 matrix assembly/keratinocyte motility leads us to put forward a model (Fig. 10). α6β4 integrin “structures” LM-332 in keratinocyte matrix by shuttling over the surface of keratinocytes. We propose that this mechanism is actin-dependent. There is support for this, because actin microfilaments act as a brake to the mobility of α6β4 integrin complexes in the plane of the membrane (65). This supposes that β4 integrin links to the actin cytoskeleton for which there is well documented evidence; β4 integrin binds actin via plectin (66, 67). That plectin, through its interaction with β4 integrin, is involved in regulating motility is also supported by other studies (34). Thus, we hypothesize that plectin regulates the ability of α6β4 integrin to organize LM-332 matrices (34, 65–69) (Fig. 10). This is consistent with data showing that the interaction of β4 with plectin stabilizes α6β4 integrin and LM-332 interaction (69). Furthermore, we propose that cofilin functions to release the brake imposed by plectin/actin, allowing α6β4 integrin to become dynamic, thereby mediating LM-332 track assembly. This mechanism has a parallel. Integrin receptors move along actin cables and remodel fibronectin matrices leading to fibronectin fibril assembly (46).

In summary, we have provided new insight into the molecular mechanisms governing how LM-332 is organized in the matrix of keratinocytes. Moreover, we have shown that the organizational state of LM-332 dictates keratinocyte motile behavior. How the assembly of the exquisite arrays of LM-332 in the extracellular matrix is regulated is key to understanding the migration patterns of keratinocytes during wound healing in the skin and skin tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and videos 1– 6.

The abbreviations used are: LM, laminin; JEB, junctional epidermolysis bullosa; GFP, green fluorescent protein; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; CMV, cytomegalovirus; TIRF, total internal reflection fluorescence; WT, wild type; DN, dominant negative; CA, constitutively active.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant RO1 AR054184 (to J. C. R. J.) and by NIH Training Grant T32 AR007593 (to B. U. S.).

References

- 1.Martin P. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilcher BK, Jones JCR, Parks WC. In: Cell Invasion. Heino J, Kahari V-M, editors. Landes Bioscience; Georgetown, TX: 2002. pp. 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldfinger LE, Hopkinson SB, deHart GW, Collawn S, Couchman JR, Jones JCR. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2615–2629. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen BP, Gil SG, Carter WG. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31896–31907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aumailley M, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Carter WG, Deutzmann R, Edgar D, Ekblom P, Engel J, Engvall E, Hohenester E, Jones JCR, Kleinman HK, Marinkovich MP, Martin GR, Mayer U, Meneguzzi G, Miner JH, Miyazaki K, Patarroyo M, Paulsson M, Quaranta V, Sanes JR, Sasaki T, Sekiguchi K, Sorokin LM, Talts JF, Tryggvason K, Uitto J, Virtanen I, von der Mark K, Wewer UM, Yamada Y, Yurchenco PD. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kainulainen T, Autio-Harmainen H, Oikarinen A, Salo S, Tryggvason K, Salo T. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosmehl H, Berndt A, Strassburger S, Borsi L, Rousselle P, Mandel U, Hyckel P, Zardi L, Katenkamp D. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:1071–1079. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyke C, Salo S, Ralfkiaer E, Romer J, Dano K, Tryggvason K. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4132–4139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niki T, Kohno T, Iba S, Moriya Y, Takahashi Y, Saito M, Maeshima A, Yamada T, Matsuno Y, Fukayama M, Yokota J, Hirohashi S. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katayama M, Sekiguchi K. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:277–286. doi: 10.1023/b:hijo.0000032359.35698.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Fu W, Im J, Zhou Z, Santoro S, Iyer V, DiPersio CM, Yu QC, Quaranta V, Al-Mehdi A, Muschel RJ. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:935–941. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortiz-Urda S, Garcia J, Green CL, Chen L, Lin Q, Veitch DP, Sakai LY, Lee H, Marinkovich MP, Khavari PA. Science. 2005;307:1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1106209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JCR, Hopkinson SB, Goldfinger LE. BioEssays. 1998;20:488–494. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199806)20:6<488::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bannon LJ, Goldfinger LE, Jones JCR, Green KJ. In: Cell Adhesion. Beckerle M, editor. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. pp. 324–368. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank DE, Carter WG. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1351–1363. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marinkovich MP, Lunstrum GP, Burgeson RE. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17900–17906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vailly J, Verrando P, Champliaud MF, Gerecke D, Wagman DW, Baudoin C, Aberdam D, Burgeson R, Bauer E, Ortonne JP. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsui C, Wang CK, Nelson CF, Bauer EA, Hoeffler WK. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23496–23503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldfinger LE, Stack MS, Jones JCR. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:255–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amano S, Scott IA, Takahara K, Koch M, Gerecke DR, Keene DR, Hudson DL, Nishiyama T, Lee S, Greenspan DS, Burgeson RE. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22728–22735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veitch DP, Nokelainen P, McGowan KA, Nguyen TT, Nguyen NE, Stephenson R, Pappano WN, Keene DR, Spong SM, Greenspan DS, Findell PR, Marinkovich MP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15661–15668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirosaki T, Mizushima H, Tsubota Y, Moriyama K, Miyazaki K. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22495–22502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baudoin C, Fantin L, Meneguzzi G. J Invest Derm. 2005;125:883–888. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quaranta V. Science. 1997;277:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenk S, Hintermann E, Bilban M, Koshikawa N, Hojilla C, Khokha R, Quaranta V. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:197–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter WG, Ryan MC, Gahr PJ. Cell. 1991;65:599–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90092-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.deHart GW, Healy KE, Jones JCR. Exp Cell Res. 2003;283:67–79. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones JCR, Kurpakus MA, Cooper HM, Quaranta V. Cell Reg. 1991;2:427–438. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.6.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowling J, Yu Q-C, Fuchs E. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:559–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1873–1884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mercurio AM, Rabinovitz I, Shaw LM. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:541–545. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikolopoulos SN, Blaikie P, Yoshioka T, Gio W, Giancotti FG. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolopoulos SN, Blaikie P, Yoshioka T, Guo W, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Giancotti FG. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6090–6102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6090-6102.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santoro MM, Gaudino G, Marchisio PC. Dev Cell. 2003;5:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell AJ, Fincher EF, Millman L, Smith R, Vela V, Waterman EA, Dey CN, Guide S, Weaver VM, Marinkovich MP. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3543–3556. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hintermann E, Bilban M, Sharabi A, Quaranta V. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:465–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choma DP, Pumiglia K, DiPersio CM. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3947–3959. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur P, McDougall JK, Cone R. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1261–1266. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-5-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langhofer M, Hopkinson SB, Jones JCR. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:753–764. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.3.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuruta D, Hopkinson SB, Lane K, Werner ME, Cryns VL, Jones JCR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38707–38714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirotani H, Tuohy NA, Woo JT, Stern PH, Clipstone NA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13984–13992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agnew BJ, Minamide LS, Bamburg JR. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17582–17587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzales M, Haan K, Baker SE, Fitchmun MI, Todorov I, Weitzman S, Jones JCR. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:259–270. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vidal F, Aberdam D, Miquel C, Christiano AM, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, Ortonne J-P, Meneguzzi G. Nat Genet. 1995;10:229–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Schwarzbauer J. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3269–3276. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.deHart GW, Jones JCR. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;57:107–117. doi: 10.1002/cm.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Bradley Dickerson J, Guo F, Zheng J, Zheng Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7618–7623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307512101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancelas JA, Lee AW, Prabhakar R, Stringer KF, Zheng Y, Williams DA. Nat Med. 2005;11:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nm1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dawe HR, Minamide LS, Bamburg JR, Cramer LP. Curr Biol. 2003;13:252–257. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghosh M, Song X, Mouneimne G, Sidani M, Lawrence DS, Condeelis JS. Science. 2004;304:743–746. doi: 10.1126/science.1094561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mouneimne G, Soon L, DesMarais V, Sidani M, Song X, Yip SC, Ghosh M, Eddy R, Backer JM, Condeelis JS. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:697–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danen EHJ, von Rheenen J, Franken W, Huveneers S, Sonneveld P, Jalink K, Sonnenberg A. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:515–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagata-Ohashi K, Ohta Y, Goto K, Chiba S, Mori R, Nishita M, Ohashi K, Kousaka K, Iwamatsu A, Niwa R, Uemura T, Mizuno K. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:465–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGowan KA, Marinkovich MP. Micro Res Tech. 2000;51:262–279. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001101)51:3<262::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raymond K, Kreft M, Janssen H, Calafat J, Sonnenberg A. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1045–1060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rabinovitz I, Gipson IK, Mercurio AM. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:4030–4043. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colognato H, Winkelmann DA, Yurchenco PD. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henry MD, Satz JS, Brakebusch C, Costell M, Gustafsson E, Fässler R, Campbell KP. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1137–1144. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P. Nature. 1998;393:805–809. doi: 10.1038/31729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Nature. 1998;393:809–812. doi: 10.1038/31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–259. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsuruta D, Hopkinson SB, Jones JCR. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;54:122–134. doi: 10.1002/cm.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Litjens SH, Koster J, Kuikman I, van Wilpe S, de Pereda JM, Sonnenberg A. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4039–4050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiche G. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2477–2486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rezniczek GA, de Pereda JM, Reiper S, Wiche G. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:209–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Geuijen CA, Sonnenberg A. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3845–3858. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.