Abstract

Overexpression and activation of the c-Src protein have been linked to the development of a wide variety of cancers. The molecular mechanism(s) of c-Src overexpression in cancer cells is not clear. We report here an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) in the c-Src mRNA that is constituted by both 5′-noncoding and -coding regions. The inhibition of cap-dependent translation by m7GDP in the cell-free translation system or induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatoma-derived cells resulted in stimulation of the c-Src IRES activities. Sucrose density gradient analyses revealed formation of a stable binary complex between the c-Src IRES and purified HeLa 40 S ribosomal subunit in the absence of initiation factors. We further demonstrate eIF2-independent assembly of 80 S initiation complex on the c-Src IRES. These features of the c-Src IRES appear to be reminiscent of that of hepatitis C virus-like IRESs and translation initiation in prokaryotes. Transfection studies and genetic analysis revealed that the c-Src IRES permitted initiation at the authentic AUG351, which is also used for conventional translation initiation of the c-Src mRNA. Our studies unveiled a novel regulatory mechanism of c-Src synthesis mediated by an IRES element, which exhibits enhanced activity during cellular stress and is likely to cause c-Src overexpression during oncogenesis and metastasis.

Keywords: RNA/Ribosome Assembly, Translation, Translation/Control, Translation/Regulation Eukaryote, RNA Folding, c-Src, cap-independent Translation, Internal Ribosome Entry Site

Introduction

Most eukaryotic mRNAs are translated by a cap-dependent mechanism where eIF4F complex binds to the 5′ cap structure through its eIF4E subunit (1, 2). This binding event results in activation of mRNA and assembly of the 48 S preinitiation complex. The 48 S complex scans mRNA in a 5′ to 3′ direction until an appropriate AUG initiation codon is encountered, which is followed by joining of the 60 S subunit (1). Many cellular conditions such as apoptosis, stress, mitosis, heat shock, hypoxia, infections, and nutrient deficiency alter the function of normal translation initiation machinery. This is largely affected by post-translational modifications (e.g. phosphorylation) and/or cleavage of canonical initiation factors (e.g. eIF4B, eIF3, eIF2a, and eIF4G family members) (1, 3, 4). A considerable number of cellular and viral mRNAs have been shown to be translated by a cap-independent mechanism due to the presence of an IRES3 element in the mRNAs (5, 6). Nearly 125 IRES elements have been described in a variety of species ranging from viruses to humans (see Ref. 3 for lists of IRESs). The IRES elements have been detected in a number of eukaryotic mRNAs that encode proteins involved in signal transduction pathways, gene expression and development, differentiation, apoptosis, and cell cycle or stress response (1, 2, 7). For example, cellular stress causes dephosphorylation of eIF4E and hypophosphorylation of 4E-BPs, both of which are unfavorable for the assembly of translation preinitiation complex by the cap-dependent mechanism (1, 8). However, under these conditions, Bcl-2, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis, eIF4G, vascular endothelial growth factor, ornithine decarboxylase, platelet-derived growth factor, PITSLRE, c-Myc family members, and a whole host of proteins maintain their presence because of their IRES-controlled translation (3, 6, 9–11, 15).

All of the viral and cellular IRESs initiate translation of a downstream open reading frame (ORF) by a cap-independent mechanism despite their rich structural diversities (12). The distinct structural features allow the IRESs to attract a different set of canonical and noncanonical translation factors for their efficient activities and/or regulation. For example, some of the viral and cellular IRESs require initiation factors such as eIF4G and poly(A)-binding protein, whereas others show enhanced activities when these factors are cleaved or their function is inactivated (2). A few of the IRESs seek support from IRES-specific trans-acting factors such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein family members, polypyrimidine tract-binding protein, lupus-associated antigen, and poly(rC)-binding protein for their efficient function (11, 13–15). The IRESs also exhibit variations in the mode of assembly of preinitiation complex. Poliovirus-like IRESs recruit the 48 S preinitiation complex upstream of the initiation site and require scanning of the complex for the initiator AUG codon, whereas an extensively studied encephalomyocarditis virus IRES recruits the preinitiation complex at the initiation site that includes AUG (3, 12). The IRESs of hepatitis C virus (HCV, a hepacivirus), classical swine fever virus (a pestivirus), cricket paralysis virus (a dicistrovirus), and simian picornavirus type 9 constitute a distinct class because of their ability to directly bind and make multiple contacts with the 40 S ribosomal subunit (12, 16–18). The assembly of productive initiation complexes on these IRESs is energy-efficient and can ignore the need of several critical translation initiation factors (eIFs 4F/4A/4B/1/1A) that are controlled by a variety of external and internal cellular regulators (15, 19). This “40 S-binding signature” has not been reported for the known cellular IRESs.

Translational dysregulation of a whole host of mRNAs has been observed in many diseases, including cancer. This is caused by a breakdown of the translational control mechanism, aberrant levels of translation factors, and/or undesirable mutations in these factors (2, 9, 20). The level of c-Src protein, a prominent member of the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase family, is known to increase in a variety of tumors (21–25). However, it is not known whether the enhanced expression is regulated by transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional mechanisms. The c-Src protein promotes cell differentiation, tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis (24–27). It activates STAT3, which transcriptionally regulates expression of Bcl-XL, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 leading to activation of anti-apoptotic and cell cycle progression pathways (28, 29). It has been shown that the activated c-Src-focal adhesion kinase complex promotes cell mobility, cell cycle progression, and cell survival. The c-Src activities are also important for promoting vascular endothelial growth factor-associated tumor angiogenesis and protease-associated metastasis (30).

Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and myristoylation are key regulators of the c-Src activities. Although nonmyristoylated c-Src readily moves to the nucleus at G0 and at the G1/S phase, myristoylation at the N terminus is required for its membrane attachment and transforming activities (31, 32). The intramolecular interaction between its Src homology 2 domain and phosphorylated Tyr-530 residue (numbered according to GenBankTM accession number NM_198291) at the C terminus induces closed or inactive conformation in the c-Src molecule. Under basal conditions in vivo, 90–95% of Src is found in this state (33). The dephosphorylation of Tyr-530 by protein-tyrosine phosphatase and autophosphorylation of Tyr-419 by its kinase domain causes induction of an enzymatically active, open conformation (25, 27).

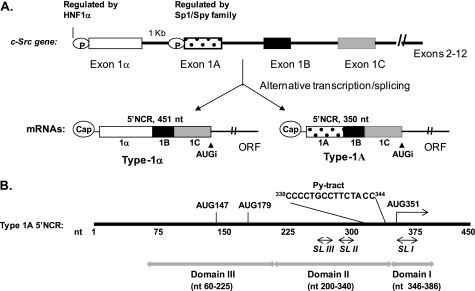

The Src gene is composed of 14 exons (34, 35). Transcription of this gene in hepatoma cells from two different promoters and alternative splicing results in mature transcripts that differ only in the extreme 5′ ends but encode the same 60-kDa c-Src protein (Fig. 1A). The c-Src type 1A mRNA contains a 350-nt-long 5′-noncoding region (5′NCR) or a 5′-untranslated region with multiple AUGs located at nt positions 147, 179, and 351 (Fig. 1B). However, only AUG351 is used to initiate translation of the c-Src open reading frame (ORF). The type 1α c-Src transcript contains a 451-nt-long 5′NCR and differs with type 1A only in the first exon (type 1A or type 1α) (35). The second and third exons (1B and 1C) are shared in both transcripts. Hepatoma cells have been shown to express both transcripts (35). The regulatory role(s) of these noncoding/untranslated elements during translation of c-Src mRNAs and their role(s) in c-Src overexpression are not known. Here, we report the presence of an IRES element in the c-Src mRNAs that is constituted by both noncoding and coding regions. This IRES possesses many unique attributes not found in the known cellular IRESs. The data presented here show that the c-Src IRES features are reminiscent of that of HCV-like IRESs and/or translation initiation in prokaryotes. Thus, our findings have opened up new avenues for investigation on the translation control of c-Src synthesis and its effects on tumorigenesis.

FIGURE 1.

A, organization of the c-src gene. Transcription from two promoters (indicated as P) and alternative splicing result in type 1α (GenBankTM accession number NM_005417) and type 1A (GenBankTM accession number NM_198291) mRNAs in liver cells. Both transcripts differ only in the 5′-distal region of the 5′NCR. The sequence of the exons 1B and 1C and ORF are shared in both transcripts (35). AUGi, initiator AUG codon. B, schematic of the type 1A 5′NCR. Two cryptic AUGs at nt 147 and 179, the initiator AUG at nt 351, and a pyrimidine tract (nt 330–344) located 6 nt upstream of the initiator AUG are shown. The gray lines with arrows on both sides show sequence locations in different putative domains, whereas similar arrows with black solid lines indicate position of the conserved stem-loop structures as shown in Fig. 2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs

Total RNA was isolated from the hepatoma-derived Huh7 cell line using Qiagen RNeasy kit. Nucleotides 1–383 of the type 1A c-Src mRNA were amplified from the total RNA using the high fidelity reverse transcription- PCR kit (Promega) and a pair of primers (sense, 5′-CATAGCAAGCTTGCCGGAGCGGCCAGGCCGCCGTCTGC-3′;antisense, 5′-GCGCCGCTGTCATGAGGCATCCTTGGGCTTGCTCTTGTTGCTACC-3′, restriction enzymes sites are underlined). The amplified DNA contains wild type full-length 5′NCR and a 33-nt coding region that encodes the first 11 amino acids of the c-Src protein. The PCR products were digested with HindIII and BspHI for ligation into a vector backbone. The backbone was created by digestion of a previously described plasmid pT7C1-DC29–332 (36) with HindIII and NcoI, and the PCR products were ligated at this site after restriction digestion. The resulting plasmid p5′Src-FLuc contains a T7 promoter at the 5′ end of the c-Src sequence that is followed by ORF of firefly luciferase (FLuc) and ends with an oligo(A) tail. The in vitro transcription of the HpaI-digested plasmid by T7 RNA polymerase produces an RNA containing the entire 5′NCR followed by coding sequences representing the N-terminal 11 amino acids (MGSNKSKPKDA) of c-Src fused with the FLuc ORF ending with a poly(A) tail. The plasmid p5′SrcΔC-FLuc was similarly constructed as described for p5′Src-FLuc except that it lacks 33 nt of the c-Src coding sequence. To construct this plasmid, the c-Src PCR-amplified DNA described above was digested with HindIII and NcoI and cloned at the same site in the vector backbone. In both cases, the Kozak sequence context was maintained at the translation site. The sequence of each construct was verified by restriction enzyme digestion and the Big Dye DNA sequencing method (Applied Biosystems).

The mutant plasmids p5′SrcΔ1-FLuc, p5′SrcΔ2-FLuc, and p5′SrcΔ3-FLuc are derived from the p5′Src-FLuc except that these plasmids have deletions of 19 (nt 216–350), 253 (nt 95–348), and 171 bases (nt 47–216) in the c-Src motif, respectively. The plasmids were constructed by appropriate restriction digestion and religation of the open ends. A Dual-Luciferase plasmid construct (p5′Src-RFLuc) was engineered, which contains the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) gene and stop codon upstream of the c-Src 5′NCR in the original plasmid p5′Src-FLuc.

The plasmid 5′PV-FLuc contains wild type, full-length poliovirus (PV, Mahoney strain) 5′NCR (nt 1–742) cloned in-frame with FLuc ORF followed by the poly(A) tail. The mutant plasmid 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc was constructed by restriction enzyme digestion of the 5′PV-FLuc plasmid with BlpI and BsaBI followed by filling with T4 DNA polymerase and religation with Quick T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). The resulting plasmid contains a deletion of 319 bp (nt 286–605) in the PV 5′NCR.

In Vitro Transcription

The plasmids p5′Src-FLuc, p5′SrcΔ1- FLuc, p5′SrcΔ2-FLuc, p5′SrcΔ3-FLuc, and p5′SrcΔC-FLuc were linearized with HpaI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase to produce luciferase reporter RNAs. The uncapped RNAs were prepared with RiboMax large scale RNA production kit (Promega). The capped RNAs were synthesized in the presence of the ARCA cap analogue using mMessage mMachine ultra kit (Ambion) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The transcribed RNAs were passed through G-25 column and purified by extraction with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol followed by water-saturated cold ether. Following precipitation and washing with 70% ethanol, the final preparations were dissolved in RNase-free water and checked for integrity of RNAs by formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis. Concentrations of RNA were determined spectrophotometrically. For preparation of the c-Src NCR probe, 5′Src-FLuc was linearized with XbaI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]CTP. The 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc was similarly digested with XbaI and transcribed for preparation of an inactive IRES control probe. The probes were purified using Qiagen RNeasy purification method. The plasmid pRL-HCV1b encodes upstream Renilla luciferase followed by the HCV IRES (nt 1–357 of the HCV genotype 1b) linked to the second reporter FLuc (37). The plasmid was linearized with HindIII and transcribed in the presence of cap analogue using T7 RNA polymerase.

Cell Culture and Preparation of Cell Lysates

Huh7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 1× penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. HeLa S3 cultures were carried out in spinner flask containing Joklik-modified minimum essential medium Eagle's (Sigma) supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum, 2% fetal clone II (Hyclone), 1× penicillin/streptomycin, and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

HeLa translation lysates (S10) and lysates containing initiation factors (IFs) were prepared according to the protocol described by Barton et al. (38). The rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) nuclease-treated was purchased from Promega. The total lysates from cultured Huh7 cells were prepared using M-PER kit (Pierce) as instructed.

In Vitro Translation of RNAs

The in vitro transcribed wild type 5′Src-FLuc and its mutant derivatives were translated in HeLa cell-free system. The standard HeLa cell-free translation mixtures contain 20 μl of S10, 10 μl of initiation factors, 5 μl of 10× buffer (155 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 600 mm potassium acetate, 10 mm ATP, and 2.5 mm GTP, 300 mm phosphocreatine, 4 mg/ml creatine phosphokinase), 20 units of RNasin, 5–10 μg of RNA template in a 40-μl final volume. One microliter of [35S]methionine was added for radiolabeling of the newly synthesized proteins. The translation mixtures were incubated for 1–2 h at 30 °C, and the FLuc activity was assayed using 2-μl aliquots. For detection of protein bands, the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. For detection of the 5′Src-RFLuc RNA expression, a Dual-Luciferase assay protocol (Promega) was employed, and Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were simultaneously assayed. Varying amounts of m7GDP or m7GTP were added in the standard HeLa translation mixtures for inhibition of cap-dependent translation. Unmethylated GDP or GTP served as negative control. Translation of the RNA in RRL was carried out as described in the supplier's protocol (Promega).

RNA Stability Assay

Equal amounts of 32P-labeled wild type or mutant reporter RNAs were incubated in standard HeLa translation reactions, and total RNAs were extracted from each sample using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The recovered RNAs were subjected to formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography of the dried gel. The bands of 18 S or 28 S rRNA in each lane were measured by ethidium bromide staining before drying the gels. During transfection experiments, 32P-labeled reporter RNAs (1–2 × 106 dpm) were transfected into Huh7 cells using the standard transfection method, and total RNAs were isolated. The radioactive full-length RNAs were detected by autoradiography.

Transfection of RNA into Cells

Huh7 cells were transfected with in vitro transcribed RNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 3, 5, 8, 24, and 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested and resuspended with lysis buffer (100 mm potassium phosphate pH 6.8, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5% Igepal). The samples were then subjected to two freeze-thaw cycles, and supernatants were assayed for Luc activities. For fluorescence microscopy, the cells were grown on coverslips (Fisher) followed by RNA transfection. The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde 48 h post-transfection, permeabilized, and stained with anti-firefly luciferase monoclonal antibody (Bionovus). A fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary conjugate was used to visualize the FLuc distribution in the transfected cells.

Isolation of 40 S Ribosomal Subunit

HeLa S10 lysate was prepared from HeLa S3 cells grown in a spinner flask as described by Barton et al. (38). The ribosomes were pelleted from S10 lysate by centrifugation in Ti70.1 rotor (Beckman, 45,000 rpm) for 3 h at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 50 mm KCl, and 4 mm MgCl2) at a concentration of 150 units/ml measured at A260 as described by Pisarev et al. (39). Puromycin (1 mm) and KCl (0.5 m) were added, stirred in an ice bath for 10 min, followed by incubation for 10 min at 37 °C. The mixture was then loaded onto a 10–30% sucrose density gradient and centrifuged for 16 h at 4 °C in a Beckman SW28 rotor (22,000 rpm). The peak fractions containing 40 S ribosomes (as determined by the presence of only 18 S rRNA) were pooled and concentrated in Ultracell-100 K (Millipore). The final preparation was dialyzed in buffer C (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.25 m sucrose), aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C (39).

Sucrose Density Gradient Analysis

Capped or uncapped 32P-labeled mRNAs were incubated in standard HeLa translation lysates that were treated with 1 mm GMP-PNP for 5 min in an ice bath. The mixtures were then incubated for 15 min at 30 °C, layered onto a 10–30% sucrose gradient in buffer K (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm potassium acetate, 5 mm magnesium acetate, and 2 mm dithiothreitol), and centrifuged for 3 h at 45,000 rpm and at 4 °C in an SW-51 rotor. Fractions (250 μl) were collected from the bottom of the gradient and analyzed by scintillation counter. Total RNAs from peak fractions were isolated using Qiagen RNeasy mini column for analysis of the RNA contents in the fractions.

For 40 S-IRES binary interaction assay, the 32P-labeled c-Src IRES or a nonspecific RNA probe derived from 5′PV(Δ286–605) as scrambled IRES was mixed with purified HeLa 40 S subunit in buffer K containing 20 units of RNasin in a final volume of 40 μl and incubated for 15 min at 30 °C. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by sucrose density gradient method as described above. A sample of RNA probe without 40 S was used to specify the position of the free probes during centrifugation.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Computer-generated c-Src RNA Structures

Our preliminary investigations on c-Src translation (not shown) and several published reports (21, 22, 26, 28) indicate that c-Src level is enhanced in many cell types during stress conditions that impair cap-dependent translation. This observation prompted us to examine cap-independent translation of the c-Src mRNAs. The 5′NCRs in the c-Src transcripts have been shown to be relatively longer than those in most cellular mRNAs (35). Sequence analysis revealed multiple pyrimidine-rich motifs and two cryptic AUGs with short ORFs at positions 147 and 179 in the 350-nt-long type 1A 5′NCR (Fig. 1). Only the AUG located at position 351 is known to serve as the initiator codon in this mRNA. Our nucleotide blast search using the BLASTN 2.2.20+ program (40) revealed that the exon 1C and the 11-amino acid N-terminal coding sequences are highly conserved in humans, chimpanzees, and rhesus monkeys (94–100% identity), whereas mouse sequences in this region are 76–80% identical to the reference human c-Src mRNA sequences (GenBankTM accession numbers NM_005417.3 and NM_198291).

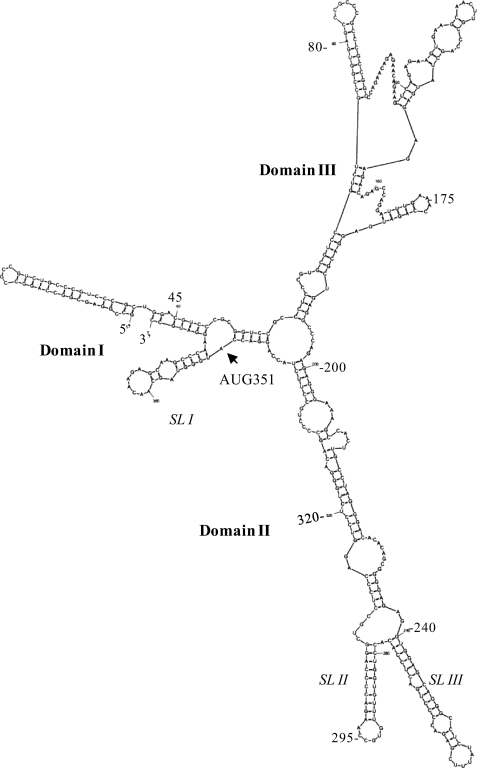

Using the M-Fold program (41), we examined a number of predicted secondary structures representing three segments (nt 1–353, 1–383, and 1–410) of the type 1A c-Src mRNA. A representative structure (dG = −135) for nt 1–383, which was found to be similar to the structure obtained for nt 1–410 segment, is shown in Fig. 2. This Y-shaped secondary structure appears to contain three domains designated as domains I–III. We further observed that a large portion of domains I and II were conserved in the structures predicted for all three c-Src segments. In addition, a high degree of conservation in the apical loops contributed by AACAAGA (nt 360–366), GUGCCA (SL II, nt 289–294), and UAUUUC (SL III, nt 255–260) motifs was also noticed in the predicted structures. The structures in domain III, however, showed less conservation among various structures generated for the three c-Src segments. A 14-nt pyrimidine (Py)-rich motif (nt 330–344) was located 6 nt upstream of the initiator AUG, which conforms with Py tracts found in many viral IRESs. These characteristics and the Y-shaped architectural features are considered as important elements of many viral and cellular IRESs (42). The predicted structure for the c-Src nt 1–353 that represents the entire 5′NCR and AUG codon lacked a significant portion of domain II structure (structure not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Computer-assisted folding of the type 1A c-Src mRNA sequence. The Zucker M-Fold program (version 3.2, 41) was used for prediction of the secondary structures representing various segments of the c-Src mRNA. Only a representative structure of the c-Src nt 1–383 that includes the entire 5′NCR followed by the 33-nt coding sequence is shown here. The initiator AUG at position 351 (arrow) and putative stem-loop (SL) structures, domains, and nt positions are indicated.

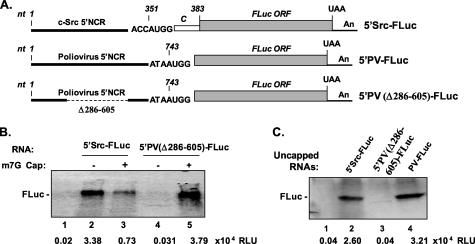

c-Src mRNA Motif Supports Cap-independent Translation of Reporter RNAs

FLuc-based reporter mRNAs were engineered to test if the c-Src 5′NCR supports cap-independent translation (Fig. 3A). Because a 33-nt sequence motif downstream of the initiator AUG in the c-Src mRNA forms a conserved stem-loop structure at the translation initiation site (Fig. 2), we included the region with the 5′NCR for engineering a parent reporter 5′Src-FLuc RNA. The RNA contains c-Src nt 1–383 (full-length 5′NCR plus 33 nt of the coding region) that is fused in-frame with luciferase ORF and ends with the poly(A) tail (Fig. 3A). In vitro transcribed capped and uncapped RNAs were translated in rabbit reticulocyte cell-free lysate (45, 46) in the presence of [35S]methionine, and the synthesized products were visualized by autoradiography. As expected, the capped 5′Src-FLuc RNA was translated to produce active luciferase protein (Fig. 3B, lane 3). Interestingly, the uncapped 5′Src-FLuc RNA was also translated but with higher efficiency (Fig. 3B, lane 2) than its capped counterpart (lane 3). During the assay, we used a reporter RNA [5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc] that contains PV 5′NCR but lacks a major portion of its IRES element (from nt 286 to 605). Thus, the noncoding region (420 nt) in the mutant PV construct represents nt 1–285 followed by nt 606–746 of the PV 5′NCR. This PV region, although known to form stable stem-loop structures, provide stability to the RNA, and bind a number of cellular factors (62), failed to support translation of FLuc in RRL (Fig. 3B, lane 4). However, synthesis of FLuc was successfully achieved when the same RNA had 5′m7G cap structure (Fig. 3B, lane 5). These results clearly demonstrate that the c-Src nt 1–383 allow cap-independent translation of downstream ORF, and its activity is enhanced when cap function is absent.

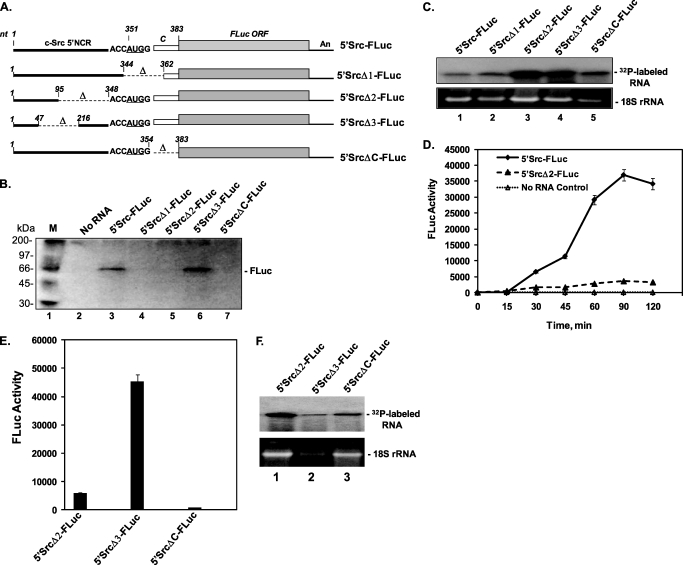

FIGURE 3.

c-Src 5′NCR-mediated translation in cell-free lysates. A, organization of in vitro transcribed uncapped reporter RNAs. The 33-nt coding sequence (dotted box, C) and Kozak sequence are shown at translation initiation site. The solid line represents 5′NCR. An, poly(A) tail. B, 5 μg of uncapped (lanes 2 and 4) and capped (lanes 3 and 5) 5′Src-FLuc (lanes 2 and 3) or 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc (lanes 4 and 5) RNAs were translated in RRL for 1.5 h in the presence of [35S]methionine. The FLuc protein bands were visualized by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE. Two μl of the translation lysates were assayed for enzymatic activity (shown as relative light units (RLU)) of FLuc using D-luciferin substrate. Lane 1, translation without exogenous RNA (control). C, translation of uncapped 5′Src-FLuc (lane 2), 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc (lane 3), and 5′PV-FLuc (lane 4) RNAs in HeLa cell-free lysate as described above. The FLuc activity and the protein bands are shown.

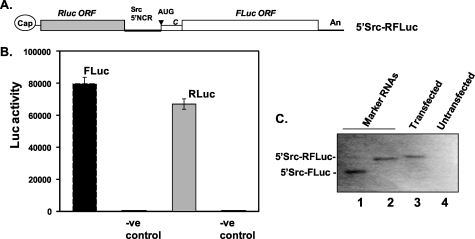

The translatability of the mRNA constructs was further tested in HeLa cell-free translation lysates that have been widely used for investigating IRES-mediated translation initiation (38). An uncapped reporter FLuc RNA that contains wild type, full-length PV 5′NCR (5′PV-FLuc, Fig. 3C, lane 4) and 5′Src-FLuc (lane 2) were efficiently translated, whereas the mutant 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc again failed to support synthesis of luciferase (lane 3). Next, we examined the c-Src 5′NCR-promoted translation in the context of a dicistronic mRNA (5′Src-RFLuc). The RNA is similar to the monocistronic 5′Src-FLuc RNA except that it contains RLuc ORF and stop codon upstream of the c-Src sequence (Fig. 4A). The in vitro transcribed capped RNA was transfected into hepatoma Huh7 cells for 3 h, and the lysates were subjected to Dual-Luciferase assay. As shown in Fig. 4B, both ORFs were translated in these cells. The capped dicistronic RL-HCV1b and RL-vector RNAs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, during the transfection. The RL-HCV-1b is similar to the 5′Src-RFLuc (Fig. 4A) except that the translation of downstream FLuc ORF is controlled by the HCV IRES instead of the c-Src IRES. In RL-vector, the c-Src IRES between upstream RLuc and downstream FLuc ORF is deleted. Both of the RNAs produced results as expected (supplemental Fig. S2). In a parallel experiment, total RNAs isolated from the dicistronic 5′Src-RFLuc RNA-transfected cells were subjected to Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe that detects the 3′ end of FLuc ORF. The result showed that the dicistronic RNA was intact in the transfected cells (Fig. 4C, lane 3). The migration of isolated RNA was similar to that of in vitro transcribed dicistronic RNA (Fig. 4C, lane 2) and was not cleaved into the monocistronic form (lane 1).

FIGURE 4.

c-Src 5′NCR-mediated translation in Huh7 cells. A, schematic of an in vitro transcribed dicistronic reporter mRNA (5′Src-RFLuc). B, Huh7 cultured cells (80% confluency, 50-mm dish) were transfected with 10 μg of capped 5′Src-RFLuc for 3 h, and Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were assayed in the cytoplasmic fractions. Each transfection was carried out in triplicate, and the experiment was repeated three times to confirm the results. The cytoplasmic fractions of untransfected cells were used as negative control. C, Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from 5′Src-RFLuc-transfected (lane 3) and untransfected (lane 4) Huh7 cells. Lanes 1 and 2 show position of monocistronic (5′Src-FLuc) and dicistronic (5′Src-RFLuc) RNAs, respectively, as RNA markers. The 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe was derived from 3′ end of the FLuc ORF. Overexposure of the film during autoradiography (for more than a week) did not show any fragment of the dicistronic mRNA in lane 3.

The 5′Src-FLuc RNA encodes a chimeric firefly luciferase with amino acids 1–11 (MGSNKSKPKDA) of the c-Src protein at its N terminus (supplemental Fig. S1A). This c-Src motif has been shown to play an important role in membrane localization and translocation of the protein into the nucleus (31, 47). Transfection of an uncapped 5′Src-FLuc RNA into Huh7 cells resulted in the synthesis of luciferase protein that was primarily localized in the nucleus and perinuclear membranes (supplemental Fig. S1B). This observation was in sharp contrast to the diffused cytoplasmic localization of luciferase that was encoded by 5′HCV-FLuc RNA in which translation of FLuc occurs under the control of HCV IRES. The resulting FLuc lacks the c-Src amino acid 1–11 motif. These results suggest that the luciferase synthesized from 5′Src-FLuc RNA contains the c-Src protein motif, which is possible when translation is initiated at the authentic AUG351 (also see Fig. 5 for translation of 5′SrcΔ1-FLuc).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of deletion mutations on the c-Src sequence-controlled translation of reporter RNAs. A, organization of in vitro transcribed uncapped wild type reporter RNA (5′Src-RFLuc) and the mutants containing various lengths of deletions (Δ) in the c-Src sequences are shown; dashed line, extent of deletion. AUG, initiator codon is underlined. B, RNAs were translated for 1.5 h in HeLa lysates in the presence of [35S]methionine, and the FLuc protein bands were visualized by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE. Lane M, 14C-labeled protein markers. C, Stability of the reporter RNAs in HeLa translation lysates. The 32P-labeled reporter RNAs (∼1 × 106 dpm) were added to a standard HeLa translation mixture for 1.5 h, and total RNAs were isolated by Qiagen RNeasy column method. Half of the eluted RNA samples (20 μl) were subjected to formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis. The gel was photographed after ethidium bromide staining for detection of ribosomal RNAs (lower panel), dried, and autoradiographed (upper panel). Reporter RNAs are as indicated for each lane. D, comparison of the kinetics of translation between wild type 5′Src-FLuc and a deletion mutant (5′SrcΔ2-FLuc). The RNAs were translated in a standard HeLa lysates mixture, and FLuc activities were assayed with an aliquot (2 μl) of the reaction at various time points. Control, translation lysates without exogenous RNA. E, transfection of uncapped monocistronic c-Src mutant RNAs. The Huh7 cells (80% confluent in 60-mm culture plates) were transfected in triplicate with uncapped RNAs as indicated, and FLuc activities were assayed 3 h post-transfection in the total lysates. F, relative stability of mutant reporter RNAs in the transfected cells. The 32P-labeled mutant RNAs (as indicated) were transfected as above. The total RNAs were isolated, and the labeled RNAs were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography of the dried gel (upper panel). Lower panel, the same gel showing 18 S rRNA in each lane.

Identification of an IRES Element in the c-Src mRNA

We introduced several deletion mutations in the c-Src motif of the 5′Src-FLuc RNA to determine its putative IRES function. The mutant 5′SrcΔC-FLuc is similar to the wild type 5′Src-FLuc RNA except that it lacks the c-Src coding sequence (nt 354–383; Fig. 5A). The mutant 5′Src-Δ1-FLuc contains a 19-nt deletion (nt 344–362). This deletion resulted in the loss of the Kozak sequence and a major portion of SL I structure at the translation initiation site (Fig. 2 and Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, both of the deletions caused dramatic reduction in the synthesis of FLuc (lanes 4 and 7) as compared with the wild type RNA (lane 3). Similarly, the 5′SrcΔ2-FLuc mutant RNA that contains a large deletion (nt 95–348) upstream of initiator AUG also failed to support efficient synthesis of FLuc (Fig. 5B, lane 5). Unlike these mutants, a 5′SrcΔ3-FLuc RNA that maintains nt 1–47 and 216–383 of the c-Src mRNA showed cap-independent translation of FLuc (Fig. 5B, lane 6) and was comparable with that of wild type 5′Src-FLuc RNA. The predicted structure of this mutant c-Src motif (data not shown) by the M-Fold program showed significant similarities in the domains I and II of the wild type structure (Fig. 2).

To determine the stability of the reporter constructs, we translated 32P-labeled uncapped mutants and wild type RNAs in HeLa cell-free lysates as described above. Total RNAs from each reaction were isolated by the RNeasy column method, and the input probes were visualized by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 5C (upper panel), the amounts of full-length mutant RNAs recovered (lanes 2–5) were similar or better than that of the wild type 5′Src-FLuc (lane 1). The quantity of 18 S rRNA (internal control) in each lane had minor variations (Fig. 5C, lower panel). This observation suggests that the mutant RNAs were present in the lysates, yet these RNAs were unable to support translation of FLuc due to absence of essential elements in the c-Src sequence motif. The different band intensities observed for the RNA probes may likely be due to minor differences in stability and/or loss during the purification process. A similar observation was also made during transfection of three mutant RNAs (Δ2, Δ3, and ΔC) into Huh7 cells. Although full-length mutant RNA probes were purified from the transfected cells (Fig. 5F), only Δ3 mutant showed efficient synthesis of reporter FLuc (Fig. 5E). These results further suggest that a functional IRES that is represented by the c-Src motif in Δ3 mutant (Fig. 2, Domains I and I,) was capable of directing translation by a cap-independent mechanism in cells as well as in the cell-free lysates. Unlike known cellular IRESs, this IRES requires a coding region for its optimal function.

We carried out kinetic analysis of translation promoted by the wild type and mutant c-Src motifs in HeLa translation lysates. The time course experiment presented in Fig. 5D shows that translation of the 5′Src-FLuc RNA exponentially increased with time, whereas the mutant 5′SrcΔ2-FLuc was translated inefficiently at all time points. During our investigations (Fig. 5, D and E), a minor translation was consistently observed for Δ2 mutant RNA. It is possible that sequence motifs that form domain I and a translation site in this RNA might have played a role in the residual translation. These motifs are, however, absent in Δ1 and ΔC mutants that are completely incompetent for translation initiation.

Assembly of 80 S Initiation Complex on the c-Src IRES in HeLa Cell-free Translation Lysates Is Not Affected by Inhibition of eIF2

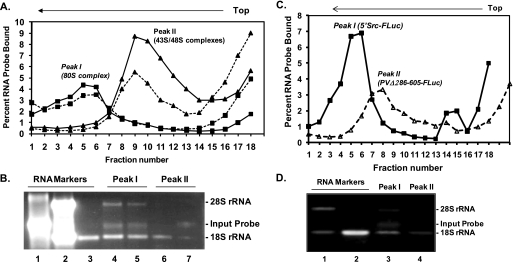

Sucrose density gradient analysis was carried out to study the assembly of 80 S translation initiation complex on the c-Src IRES. The 32P-labeled uncapped 5′Src-FLuc RNA or capped FLuc was incubated for 15 min in HeLa cell-free translation lysates containing 1 mm GMP-PNP, a nonhydrolyzable GTP analogue, which causes accumulation of 48 S complex and inhibition of 80 S formation on a capped mRNA (18, 43). The reaction mixtures were analyzed for ribosome assembly on the mRNAs by a 10–30% sucrose density gradient centrifugation method. The initiation complexes in the gradient fractions were determined by incorporation of the input RNA probe into the ribosomal complexes (Fig. 6A). A single peak (Fig. 6A, Peak I, solid line with squares) of ribosomal complex containing the input RNA probe, 18 S, and 28 S rRNA was obtained for the 5′Src-FLuc RNA (Fig. 6B, lane 4). The result clearly established assembly of the 80 S complex on the c-Src 5′NCR motif, which was not inhibited by 1 mm GMP-PNP (Fig. 6, A and B). In a similar translation reaction, we further reduced GTP and ATP concentrations by omitting the 10× reaction buffer from the translation mixture. This omission caused 10× increase in the GMP-PNP to GTP ratio during translation. Interestingly, the 80 S assembly on the 5′Src-FLuc mRNA probe occurred (Fig. 6A, Peak I, broken line with squares; Fig. 6B, lane 5) similar to the standard reaction conditions described above. On the contrary, when a capped FLuc mRNA probe that lacks the c-Src motif was used in a standard translation reaction supplemented with 1 mm GMP-PNP, only 48 S complex was obtained as expected (Fig. 6A, Peak II, solid line with triangles). This conclusion was based on the observation that peak II lacks 28 S RNA, showed lower sedimentation than peak I, and contains only input RNA probe and 18 S rRNA (Fig. 6B, lane 7). In addition, the 48 S complex assembly was considerably reduced when the cap structure was absent in the FLuc RNA probe (Fig. 6, A, Peak II, broken line with triangles, and B, lane 6). The GMP-PNP is known to inhibit GTPase function that is required for the assembly of the 80 S complex on a capped mRNA. Thus, the observed cap-independent 80 S assembly on the c-Src IRES is most likely to be independent of eIF2 function. In a similar experiment, the assembly of ribosomal complex on a mutant poliovirus 5′NCR containing FLuc (PVΔ286–605-FLuc) was compared with the 5′Src-FLuc RNA in the presence of 1 mm GMP-PNP (Fig. 6, C and D). The uncapped 5′Src-FLuc RNA showed assembly of 80 S in a reproducible manner (Fig. 6, C, Peak I, squares with solid line, and D, lane 3). However, the uncapped PVΔ286–605-FLuc RNA showed a peak at lower sucrose density (Fig. 6, C, Peak II, triangles with broken line; D, lane 4), and the complexes were spread over a wide range of sucrose density, most likely due to varying compositions of ribonucleoprotein complexes formed with the mutant PV RNA.

FIGURE 6.

Assembly of translation initiation complexes on the c-Src IRES in HeLa cell-free lysates and analysis by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. A, translation mixtures were incubated with 1 mm GMP-PNP in and ice bath for 5 min and in vitro transcribed 32P-labeled RNA as follows: 5′Src-FLuc (squares and solid line) or capped FLuc (lacking IRES, triangles and solid line) or uncapped FLuc (triangles and broken line) were added to the translation reaction and incubated for 15 min at 30 °C. The complexes formed in the absence of exogenous ATP and GTP on the 5′Src-FLuc probe are shown as squares and dashed line. The lysates were separated by 10–30% sucrose density gradient centrifugation, and fractions (250 μl) were collected from the bottom of the tube to determine RNA contents. B, total RNAs from the peak fractions (Peak I or II) were isolated and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Marker lanes are as follows: 1, input 5′Src-FLuc RNA probe; 2, total RNA extracted from HeLa S10 translation lysate showing 18 S and 28 S rRNAs; 3, 18 S rRNA extracted from purified 40 S subunit. The total RNAs extracted from Peak I (fractions 5 and 6) for 5′Src-FLuc probe are shown in lane 4, and standard translation reactions are shown as squares and solid line (A), and lane 5, translation reaction deficient in exogenous ATP/GTP (squares and broken line shown in A). RNAs isolated from Peak II are shown in lanes 6 (triangles, broken line) and 7 (triangles, solid line). C, comparison of ribosomal complex formed at wild type c-Src IRES and a mutant PV 5′NCR used as scrambled IRES in the presence of 1 mm GMP-PNP. The 32P-labeled uncapped 5′Src-FLuc (squares and solid line) or 5′PV(Δ286–605)-FLuc (scrambled IRES, triangles and dashed line) RNAs were used in sucrose gradient centrifugation analysis as described above. D, total RNA isolated and resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis is shown. Lanes 1 and 2, rRNA (as markers) isolated from lysates and purified 40 S subunit, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, RNA isolated from Peak I and Peak II, respectively.

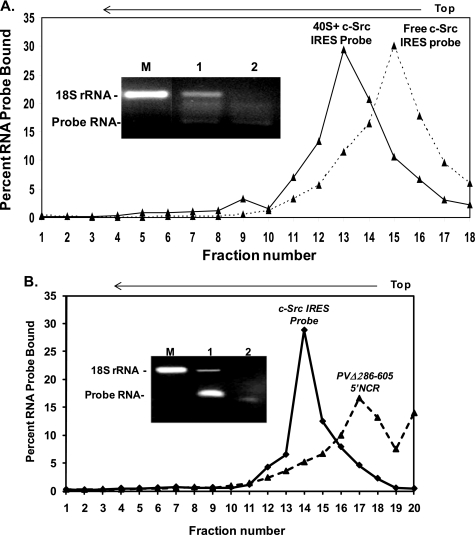

The assembly of 80 S on the c-Src IRES was further strengthened by our finding that purified HeLa 40 S ribosomal subunit directly interacts with the c-Src IRES (Fig. 7A). The purified 40 S subunit was mixed with uncapped 32P-labeled IRES fragment of the 5′Src-FLuc, and bound complex was separated from the free probe by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Characterization of the peak fractions revealed the presence of 18 S rRNA and the probe in the same peak (Fig. 7A, inset, lane 1), although the free IRES probe showed a peak at lower sucrose density. A nonspecific RNA probe of similar length and nucleotide contents (PVΔ286–605 5′NCR) failed to form the 40 S-RNA binary complex in this assay (Fig. 7B inset, lane 2). These results together provide evidence that the c-Src mRNA contains an IRES element that directly interacts with the 40 S ribosomal subunit and is capable of assembling the 80 S complex during conditions when eIF-2 function is significantly compromised.

FIGURE 7.

Direct binding of the c-Src IRES with purified HeLa 40 S ribosomal subunit. A, purified HeLa 40 S subunit was mixed with 32P-labeled RNA representing c-Src nt 1–383 (solid line) and subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation. A separate sample without 40 S was run to locate position of the free probe (broken line) during sedimentation. Peak fractions were analyzed for RNA contents (inset). Inset, lane M, 18 S rRNA as marker; lane 1, RNA extracted from 40 S plus probe peak; lane 2, RNA from free probe peak. B, experiment similar to that described in A but repeated with a scrambled IRES (5′PV(Δ286–605)) as indicated. Inset, lane M, 18 S rRNA; RNA isolated from c-Src IRES probe (lane 1) and scrambled IRES probe (lane 2).

c-Src IRES-mediated Translation Is Enhanced when Cap-dependent Translation Is Inhibited

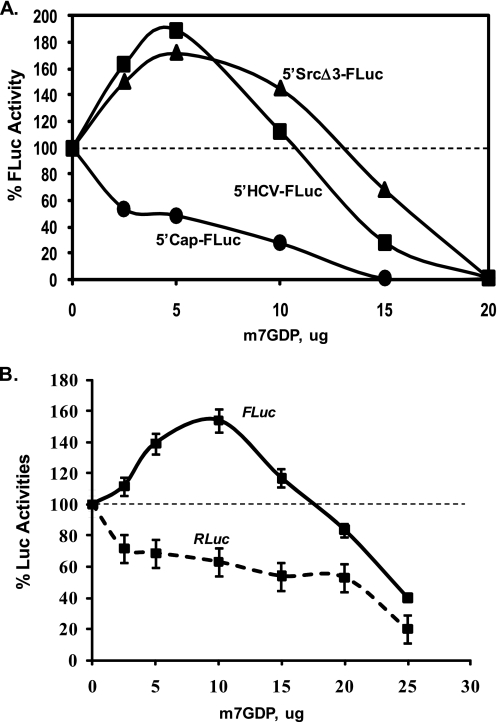

The eIF4E protein is a key translation initiation factor that binds the 5′ cap structure of an mRNA and initiates assembly of the 48 S preinitiation complex (1). It has been shown that m7GDP inhibits eIF4E function by occupying its cap-binding site. Therefore, cap-dependent translation is efficiently inhibited by the m7GDP cap analogue (44). The cap-dependent translation of a FLuc RNA, which contains the 5′cap and 3′ poly(A) tail at the respective ends of the luciferase ORF but lacks an IRES (5′Cap-FLuc), was inhibited by m7GDP in a dose-dependent manner in RRL (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the HCV IRES-controlled translation of a reporter FLuc ORF (5′HCV-FLuc) was stimulated until a threshold concentration (10 μg) of m7GDP was reached. Above this concentration, both cap-dependent as well as HCV IRES-dependent translations were inhibited. Interestingly, translation of the 5′SrcΔ3-FLuc RNA (genetic organization shown in Fig. 5A) was considerably enhanced in the presence of m7GDP as observed for the HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Similar observations were also made for the uncapped wild type 5′Src-FLuc RNA (not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Stimulation of the c-Src IRES-controlled mRNA translation when eIF4E function is inhibited. A, capped RNAs as follows: 5′Src-FLuc (triangle) and FLuc (5′Cap-FLuc, circle) or uncapped 5′HCV-FLuc (square) RNAs were translated in triplicate in the presence of increasing amounts of m7GDP in RRL for 1 h, and one-tenth of each reaction mixture was assayed for FLuc activity. Average FLuc activity of three reactions is shown for each m7GDP concentration. The FLuc activity in samples without m7GDP was considered as 100% translation and compared with those containing the cap analogue (inhibitor). Similar translation reactions were carried out twice to confirm the results. B, translation of a capped Dual-Luciferase RNA construct (5′Src-RFLuc) in RRL in the presence of increasing amounts of m7GDP as described above. Relative cap-dependent translations of RLuc and c-Src IRES-dependent FLuc synthesis are shown. Each translation mixture was carried out in triplicate. The results were confirmed by three independent experiments.

Next, we examined translation of a capped dicistronic RNA (5′Src-RFLuc; Fig. 4A) in RRL in the presence of increasing concentrations of m7GDP. The wild type c-Src IRES-controlled translation of FLuc was initially enhanced in the presence of m7GDP (5–10 μg) as observed for its monocistronic counterpart, whereas the cap-dependent translation of the upstream RLuc ORF continued to decline with increasing concentrations of m7GDP (Fig. 8B). Although the requirement of inhibitor concentration to inhibit overall translation was a little higher than that of the monocistronic RNAs, the stimulation pattern of the c-Src IRES in the presence of m7GDP was similar for both mono- and dicistronic templates. During several control experiments (data not shown), we observed that the m7GTP cap analogue also causes stimulation of the c-Src IRES in HeLa and RRL cell-free translation systems, whereas the unmethylated nucleotides (GTP or GDP) had no effects within the concentration range used in our studies. These results together with those described above (Figs. 3, 5, and 6) established the presence of a functional IRES in the c-Src mRNA that can be activated when cap function is absent or significantly inhibited and/or eIF-2 activity is inadequate in the translation system.

c-Src IRES-controlled Translation Is Modestly Enhanced during Cellular Stress That Blocks Cap-dependent Translation

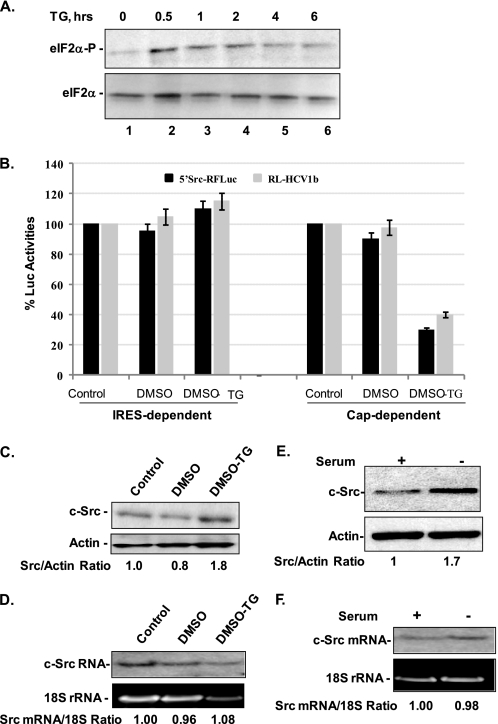

Thapsigargin (TG) causes eIF-2 phosphorylation resulting in global translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress response due to inhibition of Ca2+-ATPase activities (48, 49). We treated Huh7 cells with 1 μm TG for different time points (0.5–6 h) and monitored the status of eIF2α by Western blot. We observed a considerable increase in the phosphorylation level of eIF2α within 30 min of TG treatment, which remained elevated for 6 h (Fig. 9A, lanes 2–6, upper panel). The total eIF2α level, on the other hand, was not affected by this treatment (Fig. 9A, lower panel). The enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation may be considered as an indicator for TG-induced cellular stress and reduction in global cap-dependent translation in the treated Huh7 cells. In the subsequent experiments, Huh7 cells were pretreated with 1 μm TG for 3 h before transfection with the capped 5′Src-RFLuc or RL-HCV1b RNAs while maintaining 1 μm TG. The RL-HCV1b is similar to the 5′Src-RFLuc except that the translation of the FLuc ORF in the RNA is driven by an HCV IRES. The FLuc and RLuc activities were assayed in the cytoplasmic fractions 3 h post-transfection. The translation of reporter luciferases in untreated transfected cells (control) was considered as 100% and compared with that of DMSO- or DMSO-TG-treated cells (Fig. 9B). Both the cap-dependent and IRES-dependent (HCV or c-Src) translation was not affected by DMSO treatment of the cells. In contrast, the cap-dependent translation of RLuc was dramatically reduced for both the RNAs due to DMSO-TG treatment of the cells. In these cells, however, the c-Src or HCV IRES-controlled translation of FLuc was moderately enhanced. We also determined the expression level of natural c-Src protein in these lysates. A modest increase in the total c-Src protein level was observed in DMSO-TG-treated cell lysates as compared with the untreated (control) or DMSO alone-treated lysates (Fig. 9C). The c-Src mRNA level remained unchanged in these cells (Fig. 9D).

FIGURE 9.

c-Src IRES-controlled translation is not inhibited during cellular stress. A, phosphorylation of eIF2α by TG treatment. The cytoplasmic lysates (40 μg) from Huh7 cells that were treated with 1 μm TG for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h (lanes 2–6) were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-(phospho-eIF2α(Ser-51)) antibody (Cell Signaling, upper panel) and anti-eIF2α antibodies (Sigma, lower panel). Lane 1, 0-min treatment. B, Huh7 cells in triplicate were treated with DMSO alone or 1 μm thapsigargin dissolved in DMSO (DMSO-TG) for 3 h followed by transfection with in vitro transcribed capped 5′Src-RFLuc RNA (solid black bar) or RL-HCV1b (solid gray bar). The upstream RLuc in RL-HCV1b RNA is translated by cap-dependent mechanism, whereas HCV IRES mediates downstream FLuc translation. The cytoplasmic lysates were assayed for FLuc (IRES-dependent translation) and RLuc (cap-dependent translation) activities 3 h post-transfection. The activities of FLuc and RLuc in untreated (control) samples were considered as 100% and compared with the solvent alone (DMSO) or TG-treated cells. C, cytoplasmic lysates from experiments described in B (above) were subjected to Western blot for the total c-Src protein with monoclonal anti-Src antibody (clone 327, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, upper panel) or anti-actin antibodies (lower panel). D, Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from Huh7 cells described in B and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide corresponding to nt 320–350 of the c-Src 5′NCR (upper panel). Lower panel shows 18 S rRNA in the same samples. E, total c-Src level in Huh7 cell lysates cultured for 72 h in serum-deprived (indicated as minus) or 10% serum containing (plus) media. Western blot was carried out with anti-Src antibody as described above. F, Northern blot for probing c-Src mRNA (as described above) in total RNA extracted from Huh7 cells cultured in serum-starved (minus) and serum supplemented (plus) regular media. The 18 S rRNAs in each lane is shown in the lower panel.

Serum deprivation of cells also causes suppression of cap-dependent translation due to competitive inhibition of eIF4E binding to the 5′ cap structure by poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (50) and phosphorylation of eIF2α (4). When Huh7 cells were subjected to serum starvation, the total c-Src protein level was moderately enhanced within 72 h (Fig. 9E, minus) as compared with the control (plus), although the c-Src mRNA level was not affected (Fig. 9F). These results together complement our findings that the c-Src level in Huh7 cells is modestly enhanced or maintained to steady levels under varying cellular stress conditions that are unfavorable for cap-dependent translation. This effect is likely to occur due to increase in the c-Src IRES activities.

DISCUSSION

An overwhelming majority of reports, including polysome-profiling data, strongly advocate for IRES-dependent translation initiation of a subset of cellular mRNAs during cell division, apoptosis, cellular stress, and viral infections where cap-dependent translation initiation is compromised (reviewed in Ref. 15). Unlike known cellular IRESs, the c-Src IRES demonstrated here exhibits many unique attributes that are analogous to the characteristics of HCV-like IRESs. To identify an IRES function in viral and cellular mRNAs, mono- and dicistronic RNA-expressing plasmids have been extensively used during transfection studies. This approach, however, has been a subject of criticism due to expression via cryptic promoters and faulty transcription and splicing of the reporter constructs (51). To avoid spurious results generated by this method, we have used only in vitro transcribed capped and uncapped reporter RNAs for cell-free translation assays, transfection studies, and sucrose density gradient analyses. The transcription reactions were digested with DNase I prior to purification and checked by agarose gel electrophoresis for the absence of DNA contamination in the final RNA preparations. Furthermore, the reporter RNA transcription is under the control of the T7 promoter, and transcription of the RNA from plasmid DNA contamination is not possible in any of the systems used here. We also demonstrated that the wild type and mutant c-Src motif containing reporter RNAs were intact during various translation assays. These measures permitted us to present reliable data for the identification of c-Src IRES.

We established here that the c-Src IRES-controlled translation can be stimulated similar to the HCV IRES when eIF4E function is blocked (Fig. 8). The initiation factor eIF4E has been shown to be a negative modulator of the IRES-mediated translation, and translation of IRES-containing RNAs is accelerated when eIF4E availability is reduced (63). This is likely attributed to a decrease in eIF4F complex formation that may be accompanied by an increased availability of eIF4G/eIF4A or eIF4A RNA helicase or other initiation factors. Based on these observations, we believe that a direct binding of m7GDP to eIF-4E in our assay may lead to increased availability of translation factors that are required for efficient activities of the HCV or c-Src IRESs.

Our in vitro studies that defined the presence of an IRES in the c-Src mRNA were further corroborated by the results of transfection of mono- and dicistronic reporter RNAs into hepatoma-derived cells and induction of cellular stress in the transfected cells. Uncapped reporter RNAs containing nt 1–383 of c-Src mRNA at their 5′ ends were efficiently translated in two cell-free translation systems (RRL and HeLa lysates) and in Huh7 cells. Our genetic analysis shows that nt 200–383 of the c-Src mRNA, which harbors initiator AUG (at nt 351), plays a pivotal role in promoting cap-independent translation. An extensive analysis of the secondary and/or possible higher order structures within this region is, however, needed for accurate understanding of its role in loading productive initiation complex. We found that the c-Src IRES promotes assembly of stable 80 S complexes in the absence of cap structure and in the presence of 1 mm GMP-PNP. Under similar conditions, however, only 48 S complex can be trapped on a capped reporter RNA lacking a 5′NCR or contains a scrambled IRES. Furthermore, similar to the HCV-like IRESs, a direct binding of purified HeLa 40 S with the c-Src nt 1–383 was detected in the absence of initiation factors. These evidence together strongly support the existence of a physiologically relevant IRES element at the 5′ end of c-Src mRNA. The c-Src IRES appears to be functionally similar to the HCV IRES as both IRES elements directly interact with the purified 40 S subunit, require coding region for their functions, promote eIF2-independent assembly of 80 S complex (Figs. 3, 5 and 6) (see Refs. 19, 43, 52, 53 for the HCV IRES function), and are stimulated when eIF4E or eIF2α function is impaired (Figs. 8 and 9). Therefore, our studies reported here present several unique attributes of a cellular IRES that have been demonstrated only for HCV-like IRESs.

The sucrose gradient analyses further provided insights into the mechanism of ribosome assembly on the c-Src IRES. The nonhydrolyzable GTP analogue, GMP-PNP, blocks eIF2-dependent initiation pathway at the 48 S complex stage (18, 39). This effect was clearly evident for the cap-dependent translation initiation of the FLuc mRNA in HeLa cell-free lysates in which the 48 S complex was trapped by 1 mm GMP-PNP treatment (Fig. 6). Thus, the GMP-PNP concentration used here during translation initiation assembly was sufficient to block 80 S assembly by cap-dependent initiation mechanism in the translation mixture. In sharp contrast, assembly of 80 S complex took place on the c-Src IRES in the presence of GMP-PNP or in a reaction mixture containing the analogue but was also deficient in exogenously added ATP and GTP. Generally, 60 S subunit joins the 48 S complex to form 80 S only after eIF5-induced GTP hydrolysis and dissociation of the eIF2-GDP complex (53). This step is preceded by ATP-dependent scanning by the 48 S complex to locate the AUG codon (1). From the data presented here, c-Src IRES appears to evade both of the critical energy-dependent steps that are needed for the 80 S assembly by the cap-dependent mechanism. Because the c-Src IRES directly binds the 40 S subunit (Fig. 7) and the structural motifs from flanking regions of the initiator AUG are required for efficient function of the c-Src IRES (Fig. 5), it is highly likely that the 48 S complex formed at this element may not require energy-dependent scanning for the initiator AUG. This notion is supported by the genetic analysis of the c-Src IRES. A 19-nt deletion at translation site in 5′Src-Δ1-FLuc RNA resulted in complete impairment of the IRES function despite the presence of upstream AUG147 and AUG179. Recently, the HCV IRES was shown to switch from classical eIF2-dependent initiation to the eIF2-independent pathway under cellular stress that favors inactivation of eIF2 due to phosphorylation of its α subunit. This alternative pathway was further shown to require only eIF3 and eIF5B (an analogue of bacterial IF2) for Met-tRNAiMet delivery at the P site. Based on these observations, it was proposed that the 80 S assembly on the HCV IRES is analogous to bacteria-like mode of translation initiation (53). In this context, the c-Src IRES appears to follow HCV IRES-like mode of translation initiation when the GTPase function of the ternary complex is blocked. This conclusion is further supported by RNA transfection studies in which thapsigargin-led induction of cellular stress in Huh7 cells failed to inhibit the c-Src IRES despite increased Ser-51 phosphorylation of eIF2α as compared with the normal (unstressed) cells (Fig. 9).

The studies presented here demonstrate significant resistance of the c-Src IRES activities to the reduced level of ternary complex and eIF-2α phosphorylation. In contrast to the eIF2-dependent initiation pathway in which the eIF-2 complex delivers Met-tRNAi to 40 S subunits in a GTP-dependent manner, the eIF2A has been shown to deliver the Met-tRNAi to 40 S subunits by AUG-dependent and GTP-independent mechanisms (19, 64). In addition, a number of RNA-binding proteins have been shown to stabilize IRES structure and/or promote ribosomal complex assembly (13, 14). A comprehensive analysis is needed to ascertain whether these factors contribute to the reduced ternary complex dependence of the c-Src IRES.

In the cells, stress and serum deprivation causes inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway-dependent phosphorylation of eIF4E-BP. The unphosphorylated protein forms a tight complex with eIF4E and prevents its binding to eIF4G and the cap structure (8). Similarly, hypophosphorylation of eIF4E that is controlled by Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway also reduces its cap-binding ability. Both of these events culminate into suppression of global cap-dependent translation. In addition, phosphorylation of eIF2α by cellular kinases (e.g. PKR, PERK, HR1, and GCN2) in response to various cellular stress and viral infections leads to reduction in the level of ternary complex (eIF2-GTP- Met-tRNAiMet) due to inhibition of guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity (54). Our investigations revealed that 80 S assembly on the c-Src IRES occurs when the functions of eIF2 and eIF4E are inhibited. Therefore, it is possible that the c-Src mRNA can easily escape from tight regulation of both of these translation initiation factors, which may ultimately lead to continued c-Src protein synthesis during adverse conditions (e.g. endoplasmic reticulum stress and starvation). Enhanced c-Src level has been shown to correlate with its activated state in hepatocellular carcinoma (55). Activated c-Src is known to induce phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin and eIF4E via Ras/Raf/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, both of which favor cell survival and proliferation (56, 57). Thus, the c-Src IRES controlled translation provides an important recovery mechanism from translational blockade during cellular stress.

It has been shown that the cap-dependent translation of c-Src mRNA is regulated by elements located in its long 3′NCR through interaction with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (59). It would be interesting to investigate if heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K or microRNAs can affect the c-Src IRES-controlled translation through the 3′NCR interactions. Both transcripts of the c-src gene (type 1A and type 1α, Fig. 1A) contain conserved sequences that constitute most parts of the IRES element. However, the extreme 5′ ends in these mRNAs are dissimilar in length and nucleotide composition. It is not known if these sequences play any role in regulating the c-Src translation.

c-Src is an important player in signal transduction pathways that control oncogenesis, cell proliferation, and metastasis (24–27). The emerging strategies for treatment of breast, lung, prostate, skin, and other cancers are focused on the inhibition of c-Src activities (23, 58, 60) but not the enhanced supply of c-Src in the tumor cells. Many of the small molecules that target c-Src activities also inhibit other protein kinases and/or show high degrees of cytotoxicity (60). Adaptation for growth during cellular stress is a hallmark feature of many cancer cells, and c-Src has been shown to a play very important role during this process (61). Our study presents c-Src IRES as a new therapeutic target for treatment of cancer. Because the c-Src IRES is located downstream of the cap structure in the mRNA, interference with the IRES structure and/or function will likely result in the inhibition of cap-dependent as well as IRES-dependent c-Src synthesis. This strategy will prevent unabated c-Src supply in the cancer cells and hence is likely to reduce the chances of cancer cell survival.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to David Barton (University of Colorado, Denver) and Shahid Jameel (International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology) for helpful discussions. The plasmid pRL-HCV1b was provided by R. M. Elliott and 5′PV-FLuc by Peter Sarnow. The 5′HCV-FLuc plasmid was constructed in the laboratory of Aleem Siddiqui and reported as T7C1–341 (13, 14). We are also thankful to the members of Avidity LLC for their help.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R03AI063046 (to N. A.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

- Luc

- luciferase

- NCR

- noncoding or untranslated region

- ORF

- open reading frame

- PV

- poliovirus

- FLuc

- firefly luciferase

- RLuc

- Renilla luciferase

- TG

- thapsigargin

- RRL

- rabbit reticulocyte lysate

- GMP-PNP

- guanosine-5′-[(β,γ)-imido]triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sonenberg N., Hinnebusch A. G. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holcik M., Sonenberg N. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baird S. D., Turcotte M., Korneluk R. G., Holcik M. (2006) RNA 12, 1755–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wek R. C., Jiang H. Y., Anthony T. G. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellen C. U., Sarnow P. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1593–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannes G., Sarnow P. (1998) RNA 4, 1500–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis S. M., Cruzi S., Graber T. E., Unguent N. H., Andrews M., Holcik M. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 168–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gingras A. C., Gygi S. P., Raught B., Polakiewicz R. D., Abraham R. T., Hoekstra M. F., Aebersold R., Sonenberg N. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1422–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chappell S. A., Lausen J. P., Paulin F. E., deSchoolmeester M. L., Stoneley M., Soutar R. L., Ralston S. H., Helfrich M. H., Willis A. E. (2000) Oncogene 19, 4437–4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanbru C., Lafon I., Audigier S., Gensac M. C., Vagner S., Huez G., Prats A. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32061–32066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semler B. L., Waterman M. L. (2008) Trends Microbiol. 16, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filbin M. E., Keift J. S. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 267–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali N., Siddiqui A. (1995) J. Virol. 69, 6367–6375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali N., Siddiqui A. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2249–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spriggs K. A., Stoneley M., Bushell M., Willis A. E. (2008) Biol. Cell 100, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan E., Sarnow P. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 324, 889–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster A. M., Jan E., Sarnow P. (2006) RNA 12, 894–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pestova T. V., Shatsky I. N., Fletcher S. P., Jackson R. J., Hellen C. U. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 67–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert F., Kapp L. D., Khan S. N., Acker M. G., Kolitz S., Kazemi S., Kaufman R. J., Merrick W. C., Koromilas A. E., Lorsch J. R., Pelletier J. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4632–4644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott C. M., Proud C. G. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horn S., Meyer J., Stocking C., Ostertag W., Jücker M. (2003) Oncogene 22, 7170–7180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang Y. M., Kung H. J., Evans C. P. (2007) Neoplasia 9, 90–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serrels B., Serrels A., Mason S. M., Baldeschi C., Ashton G. H., Canel M., Mackintosh L. J., Doyle B., Green T. P., Frame M. C., Sansom O. J., Brunton V. G. (2009) Carcinogenesis 30, 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn R. S. (2008) Ann. Oncol. 19, 1379–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fizazi K. (2007) Ann. Oncol. 18, 1765–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarez R. H., Kantarjian H. M., Cortes J. E. (2006) Cancer 107, 1918–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjorge J. D., Jakymiw A., Fujita D. J. (2000) Oncogene 19, 5620–5635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaz N., Minton S., Cox C., Bowman T., Gritsko T., Garcia R., Eweis I., Wloch M., Livingston S., Seijo E., Cantor A., Lee J. H., Beam C. A., Sullivan D., Jove R., Muro-Cacho C. A. (2006) Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia R., Bowman T. L., Niu G., Yu H., Minton S., Muro-Cacho C. A., Cox C. E., Falcone R., Fairclough R., Parsons S., Laudano A., Gazit A., Levitzki A., Kraker A., Jove R. (2001) Oncogene 20, 2499–2513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitra S. K., Schlaepfer D. D. (2006) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David-Pfeuty T., Bagrodia S., Shalloway D. (1993) J. Cell Sci. 105, 613–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oneyama C., Hikita T., Nada S., Okada M. (2008) Genes Cells 13, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng X. M., Resnick R. J., Shalloway D. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 964–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonham K., Fujita D. J. (1993) Oncogene 8, 1973–1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonham K., Ritchie S. A., Dehm S. M., Snyder K., Boyd F. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37604–37611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C., Sarnow P., Siddiqui A. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 3338–3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collier A. J., Tang S., Elliott R. M. (1998) J. Gen. Virol. 79, 2359–2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barton D. J., Morasco B. J., Flanegan J. B. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 275, 35–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisarev A. V., Unbehaun A., Hellen C. U., Pestova T. V. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 430, 147–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z., Schwartz S., Wagner L., Miller W. (2000) J. Comput. Biol. 7, 203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zuker M. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le S. Y., Maizel J. V., Jr. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 362–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pestova T. V., de Breyne S., Pisarev A. V., Abaeva I. S., Hellen C. U. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 1060–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kentsis A., Volpon L., Topisirovic I., Soll C. E., Culjkovic B., Shao L., Borden K. L. (2005) RNA 11, 1762–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michel Y. M., Poncet D., Piron M., Kean K. M., Borman A. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32268–32276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soto Rifo R., Ricci E. P., Décimo D., Moncorgé O., Ohlmann T. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Resh M. D. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1451, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chao T. S., Abe M., Hershenson M. B., Gomes I., Rosner M. R. (1997) Cancer Res. 57, 3168–3173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong W. L., Brostrom M. A., Kuznetsov G., Gmitter-Yellen D., Brostrom C. O. (1993) Biochem. J. 289, 71–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seal R., Temperley R., Wilusz J., Lightowlers R. N., Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z. M. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 376–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozak M. (2007) Gene 403, 194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynolds J. E., Kaminski A., Kettinen H. J., Grace K., Clarke B. E., Carroll A. R., Rowlands D. J., Jackson R. J. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 6010–6020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terenin I. M., Dmitriev S. E., Andreev D. E., Shatsky I. N. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandez J., Yaman I., Sarnow P., Snider M. D., Hatzoglou M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19198–19205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito Y., Kawakatsu H., Takeda T., Sakon M., Nagano H., Sakai T., Miyoshi E., Noda K., Tsujimoto M., Wakasa K., Monden M., Matsuura N. (2001) J. Hepatol. 35, 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karni R., Gus Y., Dor Y., Meyuhas O., Levitzki A. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5031–5039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vojtechová M., Turecková J., Kucerová D., Sloncová E., Vachtenheim J., Tuhácková Z. (2008) Neoplasia 10, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giaccone G., Zucali P. A. (2008) Ann. Oncol. 19, 1219–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naarmann I. S., Harnisch C., Flach N., Kremmer E., Kühn H., Ostareck D. H., Ostareck-Lederer A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18461–18472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma W. W., Adjei A. A. (2009) CA-Cancer J. Clin. 59, 111–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto N., Mammadova G., Song R. X., Fukami Y., Sato K. I. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 4623–4633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murray K. E., Roberts A. W., Barton D. J. (2001) RNA 7, 1126–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Svitkin Y. V., Herdy B., Costa-Mattioli M., Gingras A. C., Raught B., Sonenberg N. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10556–10565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zoll W. L., Horton L. E., Komar A. A., Hensold J. O., Merrick W. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37079–37087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]