Abstract

p62, also known as sequestosome1 (SQSTM1), A170, or ZIP, is a multifunctional protein implicated in several signal transduction pathways. p62 is induced by various forms of cellular stress, is degraded by autophagy, and acts as a cargo receptor for autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated targets. It is also suggested to shuttle ubiquitinated proteins for proteasomal degradation. p62 is commonly found in cytosolic protein inclusions in patients with protein aggregopathies, it is up-regulated in several forms of human tumors, and mutations in the gene are linked to classical adult onset Paget disease of the bone. To this end, p62 has generally been considered to be a cytosolic protein, and little attention has been paid to possible nuclear roles of this protein. Here, we present evidence that p62 shuttles continuously between nuclear and cytosolic compartments at a high rate. The protein is also found in nuclear promyelocytic leukemia bodies. We show that p62 contains two nuclear localization signals and a nuclear export signal. Our data suggest that the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p62 is modulated by phosphorylations at or near the most important nuclear localization signal, NLS2. The aggregation of p62 in cytosolic bodies also regulates the transport of p62 between the compartments. We found p62 to be essential for accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in promyelocytic leukemia bodies upon inhibition of nuclear protein export. Furthermore, p62 contributed to the assembly of proteasome-containing degradative compartments in the vicinity of nuclear aggregates containing polyglutamine-expanded Ataxin1Q84 and to the degradation of Ataxin1Q84.

Keywords: Cell/Trafficking, Nucleus, Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitination, NES, NLS, PML Bodies, SQSTM1, p62

Introduction

p62/SQSTM1 is a ubiquitin-binding adaptor or scaffold protein implicated in many cellular functions. Initially identified as a binding partner of Lck-tyrosine kinase (1) and atypical protein kinases C (2), it was subsequently implicated as an adaptor protein in NFκB signaling pathways after activation of tumor necrosis factor-α (3), interleukin-1 (4), and nerve growth factor (5) receptors. It has been suggested that p62 may act as a ubiquitin chain-targeting factor that shuttles substrates for proteasomal degradation (6). p62 is itself a selective autophagy substrate and can act as a cargo receptor for degradation of ubiquitinated targets by autophagy (7–10). Recently, p62 was also implicated in activation of caspase-8 after triggering of cell death receptors (11). Up-regulation of p62 is detected in several forms of human tumors, and its protein level positively correlates with aggressive progression of breast and prostate cancers (12–14). p62 is required for Ras-induced tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo (15), and recently it was demonstrated that accumulation of p62 due to blockade of autophagy was highly tumorigenic in apoptosis-deficient cells (16).

Essential for many of p62′ functions is an N-terminal PB13 domain and a C-terminal UBA domain. The PB1 domain is needed for homo-polymerization and for heterodimeric interactions with atypical protein kinases Cs, MEK5 and NBR1 (17). The UBA domain has been shown to bind non-covalently to ubiquitin (18), and expression of p62 mutants defective in ubiquitin binding are linked to the development of classical, adult onset Paget disease of the bone (19, 20).

p62 is a proteotoxic stress response protein. Its expression is strongly induced at the mRNA and protein levels by exposure to oxidants, sodium arsenite, cadmium, ionophores, proteasomal inhibitors, or overexpression of polyglutamine-expanded proteins (21, 22). It is commonly found in cytosolic inclusions together with ubiquitinated proteins and in intracellular protein aggregates in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, diseases of the liver, and myopathies (23). Immunostaining of p62 is used as a histochemical diagnostic marker along with ubiquitin and cytokeratins for different forms of human aggregopathies (24).

To this end, p62 has generally been considered to be a cytosolic protein, and little attention has been paid to possible nuclear roles of this protein. Nuclear and cytosolic compartments in interphase eukaryotic cells are separated by the two-layer membrane of the nuclear envelope. Because of the relatively small size of nuclear pores (∼50 nm) and sieve-like function of the nuclear pore complex, limiting the functional diameter of opening to 9 nm, only small water-soluble molecules like salts or small proteins can passively diffuse through the pores according to the gradient concentration. Proteins larger than ∼40 kDa have to be actively transported between both compartments by the nuclear-cytosolic transport receptors karyopherins (25). Nuclear import is usually mediated by importin-α binding to a nuclear localization signal (NLS) on the cargo protein. NLSs are short peptide sequences containing a stretch of several basic amino acids either arranged as a short monopartite NLS or as a longer bipartite NLS (26). Nuclear export is facilitated by exportin-1/CRM1 binding to a nuclear export signal (NES) formed by a stretch of four regularly spaced hydrophobic amino acids (27). Both importins and exportins interact with proteins of the nuclear pore complex (nucleoporins) to transfer their cargo proteins in and out of the nucleus. The binding and release of cargo as well as the direction of this transport is regulated by a concentration gradient of GTP- or GDP-bound forms of small GTPase Ran (28).

Unlike the cytosol, where two complementary proteolytic systems, lysosomes and proteasomes, mediate the turnover of the majority of the proteins, only the proteasomal system seems to operate in the nucleus of metazoan cells. There are no membrane-limited proteolytic organelles in the nucleus, and the recently described process of piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus seems so far to be evolutionarily limited to yeasts (29). It is believed that nuclear proteasome-mediated protein degradation occurs within distinct nucleoplasmic foci (30). These proteolytic nuclear subdomains represent a subset of the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies and are sometimes referred to as clastosomes (31, 32). They contain molecular chaperones, proteasomes, and ubiquitinated proteins and are associated with proteasome-specific proteolytic activity (30, 33). These nuclear proteolytic compartments seem to have a transient nature. Their assembly is modulated by a supply of proteasomal substrates, and their number increases under the conditions of proteotoxic stress (31–33).

The importance of nuclear protein quality control and degradation system is exemplified by the fact that eight of nine currently known polyglutamine expansion diseases are characterized by formation of preferentially nuclear or only nuclear protein aggregates (34). This also underscores the importance of studying protein degradation in the nucleus, as novel mechanistic insight may unleash a great therapeutic potential.

In this study we demonstrate that p62 undergoes fast nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling and identify the nuclear localization- and nuclear export signals in the protein. The shuttling is modulated by phosphorylation and aggregation of p62. We also provide evidence that p62 localizes to PML bodies and is essential for the accumulation of polyubiquitinated nuclear proteins in PML bodies upon inhibition of nuclear protein export. Interestingly, p62 also contributes to recruitment of proteasomes to nuclear aggregates of ataxin-1 and to the degradation of ataxin-1, the etiological factor of polyglutamine expansion disease spinocerebellar ataxia 1 (SCA1).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were used: anti-p62 monoclonal (BD Transduction Laboratories #610833 and Santa Cruz Biotechnology D-3 #28359); anti-p62 C-terminal guinea pig polyclonal (Progen Biotechnik); anti-PML monoclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-GFP polyclonal (Abcam Ltd.); FK1 monoclonal antibody to polyubiquitinated proteins, FK2 monoclonal antibody to mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins, and anti-proteasome 20 S core subunit polyclonal antibody (Biomol International); horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody (Pharmingen). The following fluorescent secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies AlexaFluor 488, AlexaFluor 568, and AlexaFluor 680; goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody AlexaFluor 568; goat anti-guinea pig IgG antibodies AlexaFluor 568 and AlexaFluor 633 (all from Invitrogen); goat anti-rabbit IRDye800-conjugated polyclonal antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals). Leptomycin B was purchased from Sigma. Prostate cancer tissue microarrays prepared from radical prostatectomy specimens were obtained from Håvard Danielsen, The Norwegian Radium Hospital.

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Details on their construction are available upon request. Point mutants were made using the QuikChange site- directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Gateway LR recombination reactions were done as described in the Gateway cloning technology instruction manual (Invitrogen). Oligonucleotides for mutagenesis, PCR, and DNA sequencing reactions were obtained from Operon. All plasmid constructs were verified by restriction digestion and/or DNA sequencing (BigDye; Applied Biosystems).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

wt, wild type; polyQ, polyglutamine.

Cell Transfections

Subconfluent HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine PLUS (Invitrogen). The p62 siRNA (Dharmacon; 5′-GCATTGAAGTTGATATCGAT-3′) or nontargeting siRNAs controls (Dharmacon) were transfected twice with a 24-h interval at a 20 nm final concentration using Lipofectamine 2000. For stable transfection of GFP-Ataxin1Q84 (35), HEK293 Flp-In T-Rex cells (Invitrogen) were transfected with pcDNA5/FRT/TO-GFP-Ataxin1Q84 and pOG44 plasmids, and stably transfected cells were selected with hygromycin according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblots

For immunoprecipitation experiments, cells were lysed 24 h after transfection in HA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) with phosphatase inhibitor mixture set II (Calbiochem) and Complete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (17).

Light Microscopy Analyses

The cell cultures were directly examined under the microscope or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained as described previously (17). Live cells were placed in Hanks' medium with amino acids and serum at 37 °C and imaged for up to 30 min on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with a ×40, 1.2W C-Apochroma objective equipped with an LSM510-META confocal module or up to 2 h on Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope, 60×, 1.2W objective equipped with incubation chamber with CO2 and temperature control. Tissue microarray slides were stained using a Ventana automated immunostainer as described (12). Images were collected using a Leica DM IRB light microscope equipped with Leica DFC420 digital camera. Images were processed using Canvas Version 9 (ACD Systems).

Mass Spectrometry

Gel bands were excised and subjected to in-gel reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion using 2–10 ng/μl trypsin (V511A, Promega) (36). Peptide mixtures containing 0.1% formic acid were loaded onto a nanoAcquityTM Ultra Performance LC (Waters) containing a 3-μm Symmetry® C18 Trap column (180 μm × 22 mm) (Waters) in front of a 3-μm AtlantisTM C18 analytical column (100 μm × 100 mm) (Waters). Peptides were separated with a gradient of 5–95% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, with a flow of 0.4 μl/min eluted to a Q-TOF Ultima Global mass spectrometer (Micromass/Waters) and subjected to data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Peaklists were searched against the Swiss-Prot protein sequence data base using an in-house Mascot server (Matrix Sciences, London UK). Peptide mass tolerances used in the search were 50 ppm, and fragment mass tolerance was 0.1 Da. Verification of phospho-sites was done with the BioLynx Software (Waters).

RESULTS

Endogenous p62 Is Subject to Constitutive Fast Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling

Despite the predominantly cytosolic localization of p62, we have noticed that a fraction of HeLa cells (about 15%) displays similar fluorescence intensities in the cytoplasm and nucleus, and a small fraction (0.5%) displays preferentially nuclear p62 with accumulation of p62 in the nuclear bodies 0.3–1 μm in diameter (7). Careful examination of HeLa cells stained with anti-p62 antibody revealed that even cells with predominantly cytosolic localization of p62 also contain small nuclear speckles, positively stained with anti-p62 antibody. These structures showed strong co-localization with PML bodies (also called ND10 bodies) (Fig. 1A). We also found their partial co-localization with coilin, a marker of Cajal bodies, and no co-localization with splicing factor SC-35, a marker of SC-35 speckles/interchromatin granule clusters (data not shown). The absence of nuclear speckles, staining positive for p62 in HeLa cells transfected with siRNA against p62, confirmed the specificity of staining (data not shown). To determine if nuclear localization of p62 is limited to the cell culture model or is a more general phenomenon, we stained tissue microarray slides of prostate tumors with anti-p62 antibody. To our surprise, prostate tissue samples from 31 patients (18%) displayed a nuclear staining pattern of p62 at least in a fraction of the cells, and samples from 82 other patients (48%) showed a cytosolic pattern with some nuclear staining of p62 (Fig. 1, B and C).

FIGURE 1.

p62 is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein. A, endogenous p62 colocalizes with nuclear PML bodies in HeLa cells (upper panel) and translocates to the nucleus upon LMB treatment (lower panel). Scale bar, 10 μm. B and C, p62 is present in both nuclear and cytosolic compartments in prostate cancer tissue samples. The hematoxylin/eosin-stained slides of prostate cancer tissue microarrays were labeled with anti-p62 antibody and scored for the presence of p62 in the nucleus, cytosol, or both compartments. Numbers inside the bars represent the number of individual tissue samples assigned to each group. D, quantification of nuclear import speed of p62 is shown. HeLa cells were treated with LMB for indicated time periods, fixed, labeled with anti-p62 antibody, and scored as nuclear, nuclear/cytosolic, or cytosolic based on the intensity of p62 staining. Each time point represents the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments with more than 200 cells counted per experiment.

Proteins larger than 40 kDa usually cannot enter or leave the nucleus by passive diffusion and are transported actively as a cargo by karyopherins (25). To determine whether the export of p62 out of the nucleus is dependent on the activity of exportin-1 (mammalian homolog of CRM1 nuclear export karyopherin), we treated HeLa cells with its specific inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB). Interestingly, LMB treatment induced a rapid redistribution of endogenous p62 to the nucleus with t½ ≈ 10–15 min (Fig. 1, A and D). This suggests that subcellular localization of p62 in resting cells is extremely dynamic and indicates that p62 is shuttling fast between the nucleus and cytoplasm.

p62 Contains a Leucine-rich Nuclear Export Signal between Amino Acids 303 and 320

Accumulation of p62 in the nucleus upon LMB treatment suggests that it either contains a classical leucine-rich NES, recognized by exportin-1, or it is exported bound to a NES-containing interaction partner. Close examination of the amino acid sequence of human p62 reveals that it contains a motif between amino acids 303 and 320 resembling the consensus sequence of leucine-rich NES (Fig. 2A) (37, 38). This region of p62 is predicted to form an amphipathic α-helix with three consensus hydrophobic residues projecting from one side of the helix and the last consensus leucine located on the opposite side of the α-helix. A similar topological distribution of consensus hydrophobic residues is described for NESs in several proteins (39). Interestingly, two commonly used commercially available mouse monoclonal antibodies produced against either amino acids 257–437 (BD Transduction Laboratories #610833) or amino acids 151–440 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #28359) of p62 recognize the predicted NES motif as an antigenic epitope (Fig. 2B). Thus, this region of p62 is likely to be surface-exposed and have a stable conformation. To determine whether this motif in p62 is needed for its nuclear export, we generated a GFP fusion construct of p62 lacking amino acids 303–320. This deletion mutant displayed a more pronounced nuclear accumulation than wild type p62 (Fig. 2, C and E), although its nuclear redistribution was not complete and was characterized by high cell-to-cell variation. This observation suggests that either p62 has other NESs, or it is bound to a NES-containing protein. It is known that p62 can homopolymerize via its PB1 domain (17, 40). Hence, we speculated that NES-deficient constructs of p62 can be exported from the nucleus in complex with endogenous p62. Indeed, GFP-p62-(Δ303–320) can immunoprecipitate endogenous p62 (Fig. 2D) and redistribute endogenous p62 to the nucleus (Fig. 2C, upper panel). siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous p62 resulted in complete translocation of GFP-p62-(Δ303–320) to the nucleus (Fig. 2, C, lower panel, and E). Similarly, a 303–320 deletion mutant of p62 containing two point mutations in the PB1 domain that disrupt its polymerization (K7A/D69A) (17) also showed complete nuclear accumulation (Fig. 2, C, middle panel, and E). Moreover, a single point mutation of the consensus isoleucine 314 to glutamate in the NES was sufficient to redistribute monomeric p62 to the nucleus (Fig. 2, C, lower panel, and E). These results demonstrate that the predicted NES at amino acids 303–320 is either the only or the major NES in p62, essential for its nuclear export.

FIGURE 2.

The region of p62 between amino acids 303 and 320 is essential for the nuclear export of p62. A, the p62 region between amino acids 303 and 320 matches the consensus sequence of classical nuclear export signals. B, the region is recognized as an antigenic epitope by two commercially available mouse monoclonal antibodies. Shown is a Western blot (WB)of cell lysates from HeLa cells transiently transfected with the indicated constructs, developed with anti-p62 or anti-GFP antibodies (BD Transduction Laboratories #610833; Santa Cruz Biotechnology #28359). The bands corresponding to the GFP-p62 fusions and endogenous p62 are indicated as GFP-p62 and p62 endo., respectively. C–E, deletion of the region between amino acids 303–320 impairs the nuclear export of p62. C, shown are representative images of HeLa cells transiently transfected with the indicated DNA constructs or siRNA and stained with anti-p62 antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories #610833) where indicated. Scale bars equal 10 μm. D, immunoprecipitation (IP) of the indicated p62 constructs containing wild type or polymerization-impaired PB1 domain from cell lysates of transiently transfected HeLa cells is shown. E, quantification of nuclear/cytosolic distribution of transiently transfected p62 constructs from panel C is shown. N, only nuclear localization; N>C, nuclear staining is stronger than cytosolic; N=C, equal nucleocytosolic staining; N<C, cytosolic staining is stronger than nuclear. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment.

To formally prove that a protein sequence functions as a nuclear export signal, it is necessary to demonstrate that its fusion to a heterologous substrate can transfer nuclear export capability to this substrate. To test whether the p62 NES we have mapped has a transferable nuclear export activity, we used a Rev(1.4)-GFP transfection-based in vivo assay (Fig. 3A) (37). The EGFP fusion construct of NES-deficient Rev (Rev1.4) protein from HIV-1 (negative control) showed intense nuclear accumulation after transient transfection into HeLa cells (Fig. 3B, upper panel). Insertion of the original NES from Rev between Rev1.4 and EGFP (positive control) resulted in redistribution of the construct to the cytosol (Fig. 3B, upper panel). Consistent with the results from the deletion analysis, insertion of the p62-(303–320) fragment between Rev1.4 and EGFP also resulted in complete redistribution of the fusion construct to the cytosol (Fig. 3B, upper panel). The accumulation of Rev1.4-p62-(303–320)-EGFP in the cytosol was dynamic and was completely blocked by treatment with LMB (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Hence, the region of p62 between amino acids 303 and 320 is indeed a nuclear export signal and not a cytosolic retention signal.

FIGURE 3.

The region of p62 between amino acids 303 and 320 is sufficient for nuclear export. A, the nuclear export activity of p62 region 303–320 was tested using the pRev1.4-GFP assay system where putative NESs were inserted between the nuclear export-impaired Rev protein from HIV and GFP. B, representative images are shown of HeLa cells transiently transfected with Rev1.4-GFP, Rev1.4-NES-GFP, or Rev1.4-p62-(303–320)-GFP vectors (upper panel). Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Rev1.4-p62-(303–320)-GFP was verified by LMB treatment (lower panel). Scale bars equal 10 μm C, quantification of nuclear/cytosolic distribution of transiently transfected constructs from panel B is shown. Labels are the same as in Fig. 2E. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment. D, overexpression of the NES from Rev or the p62 fragment 303–320 inhibits the nuclear export of endogenous (end.) p62. Representative are shown of images of HeLa cells transiently transfected with indicated constructs, stained with anti-p62 polyclonal antibody. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

CRM1-dependent nuclear export is a saturable process. Peptides containing leucine-rich nuclear export signals can specifically block exportin1-mediated nuclear export (41, 42). To test whether the NES from Rev or NES from p62 could compete with nuclear export of p62, we transfected GFP-fusion constructs of Rev-(70–87) or p62-(303–320) into HeLa cells and stained cells with an antibody recognizing the C-terminal UBA domain of p62. As expected, overexpression of both GFP-Rev-(70–87) or GFP-p62-(303–320), but not GFP alone, resulted in nuclear accumulation of endogenous p62 (Fig. 3D). These data strongly suggest that the region of p62 between amino acids 303 and 320 has the functional properties of a classical exportin-1-dependent NES similar to the NES of HIV-1 Rev protein.

p62 Contains Two Monopartite Nuclear Localization Signals

Because p62 accumulates in the nucleus after inhibition of exportin-1-mediated nuclear export, it is logical to assume that it either has a functional NLS or is imported to the nucleus in complex with other NLS-containing proteins. p62 contains two clusters of positively charged residues resembling the basic monopartite nuclear localization signal; they are amino acids 186–189 (NLS1) and amino acids 264–267 (NLS2) (Fig. 4A). To elucidate the role of these NLS-like motifs in the nuclear import of p62, we first analyzed the subcellular distribution of the GFP fusion construct of amino acids 170–302 fragment of p62 containing both putative NLSs. As expected, this construct was selectively accumulated in the nucleus of transiently transfected HeLa cells, confirming the presence of nuclear import activity (Fig. 4, B and C). Point mutations of consensus basic residues to alanine in either NLS1 or NLS2 increased the cytosolic pool of these fusion proteins but did not impair their nuclear accumulation, whereas the NLS1 and NLS2 double mutant displayed an equal distribution between the nucleus and cytosol, similar to that of GFP alone (Fig. 4, B and C).

FIGURE 4.

The region of p62 between amino acids 170 and 302 is sufficient for nuclear import. A, p62 contains two predicted basic nuclear localization sequences, NLS1, 186RKVK189 and NLS2, 264KRSR267. B and C, GFP fusion constructs of p62 fragment between amino acids 170 and 302 containing wild type (WT) or mutated NLS1 and NLS2 were transfected into HeLa cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection cells were scored based on the distribution of GFP fluorescence in the nuclear or cytosolic compartments. Representative images are shown in B. Scale bars equal 10 μm. Each bar in C represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment.

NLS2 Is Required for Efficient Nuclear Import of p62

To determine whetherNLS1 and NLS2 motifs can also direct the nuclear import of the full-length protein, we decided to compare the nuclear accumulation speed of wild type versus NLS1- or NLS2 mutants of full-length p62 after inhibition of nuclear export with LMB using live-cell confocal microscopy. The speed of nuclear accumulation of these overexpressed constructs will depend on several factors; that is, the presence and accessibility of nuclear localization signals, interaction with endogenous proteins, cell-to-cell variation in the activity of the nuclear import machinery, and the expression level of the protein being tested. To decrease this variation, all tested constructs of full-length p62 with wild type or mutated NLS1 or NLS2 also contained K7A/D69A mutations in the PB1 domain to prevent the interaction of overexpressed constructs with endogenous p62. To minimize the effect of cell-to-cell variations in the activity of nuclear import machinery and differences in overexpression level of proteins, we related the nuclear import speed of tested GFP-tagged p62-K7A/D69A constructs containing wild type or mutant NLS1 or NLS2 to the nuclear import speed of cotransfected mCherry-tagged p62-K7A/D69A containing wild type NLSs (nuclear import reference control) (Fig. 5A). To enable quantitative comparisons, we measured the time needed by overexpressed constructs to reach the same concentration in the nucleus as in the cytosol after the addition of LMB. We refer to this value as the nuclear import time. For each individual cell investigated, the relative nuclear import time was calculated as the import time of the GFP-tagged construct divided by the import time of the co-expressed mCherry-tagged reference construct. When GFP- and mCherry-tagged p62 K7A/D69A were co-expressed in HeLa cells, these constructs showed a similar nuclear import time in every individual cell investigated; hence, the relative import time of GFP-p62 K7A/D69A is 1 (Fig. 5, B and D). Mutation of two basic residues in NLS1 to alanines inhibited the nuclear import by 1.5-fold (Fig. 5, C, upper panel, and D), whereas mutation of lysine 264 and arginine 265 to alanines in NLS2 inhibited the nuclear import by 6.3-fold (Fig. 5, C, lower panel, and D). Thus, these results suggest that NLS2 is the major NLS in p62.

FIGURE 5.

NLS2 is essential for efficient nuclear import of p62. A, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with mCherry fusion construct of monomeric p62 (p62K7A/D69A; p62 shuttling reference control) together with the GFP fusion constructs of monomeric p62 containing wild type or mutated NLS1 and NLS2. Twenty-four hours after transfection, LMB was added to the culture medium to inhibit nuclear export of p62, and accumulation of GFP and mCherry fluorescence in the nuclei of the cells was imaged by live laser-scanning microscopy (B and C). The time needed for GFP- or mCherry-p62 fusion constructs to reach the same concentration in the nucleus as in the cytosol was measured and referred to as nuclear import time. To compensate for cell-to-cell variation, relative nuclear import time was calculated for each cell as a ratio between nuclear import time of GFP fusion constructs of wild type or NLS mutants (mut) of monomeric p62 and nuclear import time of the mCherry fusion construct of wild type, monomeric p62 (D). Each bar represents the mean relative nuclear import time ±S.D. for 20–35 cells from 3–6 independent experiments. Scale bars in panels B and C equal 10 μm.

Phosphorylation of Residues within or C-terminal to NLS2 Can Modulate the Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling of p62

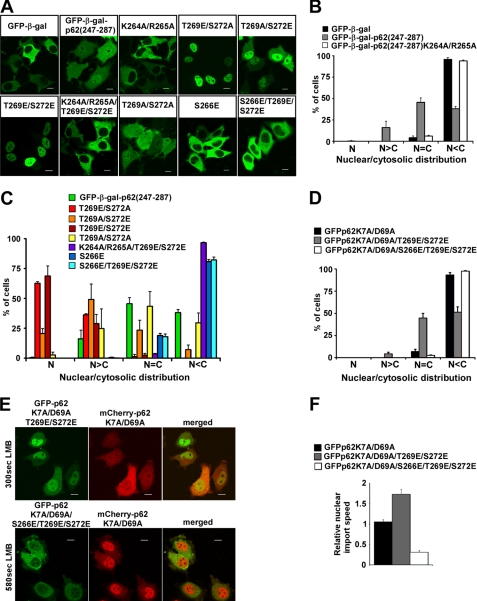

p62 has been described as a phosphoprotein and as an in vitro substrate of several protein kinases, including ERK2, protein kinase A, and casein kinase II (43). Using a mass spectrometry approach, we identified several serine and threonine residues that were phosphorylated in p62 from unstimulated HEK293 cells. Two of the phosphorylated residues are threonine 269 and serine 272, located in close proximity to NLS2 (supplemental Fig. 1). Several large phosphoproteome screens have also reported the phosphorylation of these two residues (44, 45). In addition, phosphorylation of serine 266, located in the middle of NLS2, has also been demonstrated (45). Because phosphorylation is commonly used for regulation of NLS function, we decided to test the possible effect of phosphorylation of serine 266 and 272 and threonine 269 on nuclear import of p62. To test the effect of phosphomimetic mutations of Ser-266, Thr-269, and Ser-272 on the activity of NLS2, we created a fusion construct containing a 40-amino acid fragment of p62-(247–287), fused to EGFP (for live cell imaging) and β-galactosidase (to prevent passive diffusion of the construct between the nucleus and the cytosol). As expected, both the EGFP-β-gal control and the NLS2 mutant EGFP-β-gal-p62-(247–287)-K264A/R265A were preferentially cytosolic after transient transfection of HeLa cells, whereas pEGFP-β-gal-p62-(247–287) was partially accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 6, A and B). Surprisingly, mutation of either threonine 269 or serine 272 to phosphomimetic glutamate significantly increased the nuclear accumulation of this fusion protein, with T269E and T269E/S272E mutants being almost completely nuclear. The T269E mutation gave a more pronounced nuclear accumulation than the S272E mutation (Fig. 6, A and C). This effect was dependent on a functional NLS2, as the K264A/R265A/T269E/S272E mutant was completely cytosolic (Fig. 6, A and C). On the other hand, the phosphomimetic substitution of serine 266 for glutamate alone or concomitant with the T269E/S272E double mutation completely blocked nuclear accumulation of the construct (Fig. 6, A and C). These data suggest that phosphorylation of p62 at threonine 269 and serine 272 can increase the nuclear import activity of NLS2, whereas phosphorylation of serine 266 in the middle of NLS2 has a profound inhibitory effect on nuclear import. To determine whether these results apply to full-length p62, we generated a T269E/S272E double mutant and a S266E/T269E/S272E triple mutant of GFP-p62K7A/D69A and determined their subcellular localization and nuclear import speed in transiently transfected HeLa cells. Completely consistent with the results obtained with the isolated NLS2 fragment, mutation of threonine 269 and serine 272 to glutamate increased nuclear accumulation of full-length p62 protein even in resting cells (Fig. 6D) and increased its nuclear import speed 1.7-fold (Fig. 6, E, upper panel, and F), whereas an additional mutation of serine 266 to glutamate completely blocked this effect and inhibited nuclear import of p62 (a 3.3-fold reduction) (Fig. 6, D, E, upper panel, and F). These results support our hypothesis that phosphorylation of serine 266, threonine 269, and serine 272 may play an important regulatory role in modulating nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p62.

FIGURE 6.

Phosphomimetic mutations of Ser-266, Thr-269, and Ser-272 affect the efficiency of NLS2. The fragment of p62 encompassing amino acids 247 and 287 containing NLS2 was cloned in-frame with the EGFP-β-galactosidase (EGFP-β-gal) fusion protein. The resulting fusion construct was subjected to PCR mutagenesis to generate glutamate or alanine mutations of Ser-266, Thr-269, and Ser-272. Wild type or mutant variants of this construct were transiently transfected into HeLa cells (A), and their nuclear (N)/cytosolic (C) distribution was scored 24 h after transfection (B and C). Scale bars in panel A equal 10 μm. Each bar in panels B and C represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment. D, constructs of full-length monomeric GFP-p62 with or without T269E/S272E or S266E/T269E/S272E mutations were transiently transfected into HeLa cells, and their nuclear/cytosolic distribution was scored 24 h after transfection. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment. E and F, GFP fusion constructs of full-length monomeric p62 with T269E/S272E or S266E/T269E/S272E were co-transfected with a mCherry fusion construct of full-length, monomeric p62. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated and imaged as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Cells with a similar nuclear/cytosolic distribution of GFP and mCherry fluorescence and with preferential cytosolic fluorescence before LMB treatment were selected for the calculation of nuclear import time. Relative nuclear import speed was calculated as a ratio between the nuclear import time of mCherry fusion construct of wild type monomeric p62 and the nuclear import times of GFP fusion constructs of phosphomimetic mutants of monomeric p62. Scale bars in panel E equal 10 μm. Each bar in panel F represents the mean relative nuclear import speed ± S.D. of more than 20 cells from 3–5 independent experiments.

p62 Can Recruit Nuclear Polyubiquitinated Proteins to PML/ND10 Structures

Several recent reports suggest PML/ND10 bodies to be nuclear proteolytic centers, as they can accumulate misfolded proteins, recruit proteasomal subunits, and colocalize with a reporter of proteolytic activity (30). Because p62 accumulates in PML bodies and may be able to shuttle ubiquitinated proteins for proteasomal degradation (6), we decided to test whether p62 is important for recruitment of ubiquitinated proteins to PML bodies. In resting cells the polyubiquitin-specific FK1 antibody preferentially stains cytosol with only weak diffuse nuclear staining, suggesting a low level of nuclear polyubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 7A). Increasing the amount of nuclear proteins by inhibiting nuclear export with LMB led to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in distinct nuclear foci that colocalized with p62 and PML (Fig. 7A and data not shown). Surprisingly, knockdown of endogenous p62 with siRNA prevented the recruitment of polyubiquitinated proteins to PML/ND10 nuclear bodies in LMB-treated cells (Fig. 7A). Similar results were obtained with staining with mono- and polyubiquitin-specific FK2 antibody (data not shown). Nuclear import of p62 is sensitive to ubiquitin binding, as overexpression of ubiquitin or a K29R/K48R/K63R mutant of ubiquitin that cannot form Lys9-, 48-, or 63-linked polyubiquitin chains but still can bind to p62, both inhibited nuclear accumulation of p62 after LMB treatment (Fig. 7B). Thus, it is very unlikely that nuclear foci of FK1 or FK2 staining represent polyubiquitinated proteins transported by p62 from the cytosol.

FIGURE 7.

p62 can recruit polyubiquitinated (polyUb) proteins to PML nuclear bodies. A, HeLa cells transfected with control or p62-targeting siRNA were left untreated or treated with LMB for 6 h, then fixed and stained with anti-polyubiquitin (FK1) and anti-p62 antibody. B, cells were transiently transfected with the pCW7-Myc-ubiquitin or pCW7-Myc-ubiquitin-K29R/K48R/K63R expression vectors and treated with LMB for 2 h at 24 h after transfection. The cells were fixed and stained with anti-Myc and anti-p62 antibodies. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

p62 Is Recruited to Nuclear Inclusions of Polyglutamine-expanded Ataxin1Q84 and Facilitates the Recruitment of Proteasomes to These Structures

p62 is a common component of cytosolic protein inclusions in various protein aggregation diseases (23) and plays important roles in formation and degradation of ubiquitinated cytosolic aggresome-like structures induced by cellular stress (10, 46). Several recent reports, however, indicate that p62 is not limited only to cytosolic protein inclusions but can also be found in nuclear Marinesco bodies in substantia nigra (47), in nuclear inclusions in a mouse model of Huntington disease (22), and in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (48). To test whether p62 can be recruited to the nuclear protein aggregates in resting cells, we used HeLa or HEK293 cells transfected with mutant ataxin-1 containing an expanded polyglutamine tract as model systems. Polyglutamine expansion in the nuclear protein ataxin-1 is a main etiological factor of the late-onset neurodegenerative disorder spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. It is characterized by accumulation of ubiquitinated nuclear protein inclusions formed by a pathogenic form of the ataxin-1 protein (35). Overexpression of a GFP-tagged ataxin-1 construct (35) containing a polyglutamine tract of 84 residues in HeLa cells leads to formation of spherical nuclear protein inclusions. Co-staining with anti-p62 antibody revealed that 24 h after transfection, 52% of cells contained p62 in these nuclear protein structures, and colocalization reached 82% 48 h after transfection (Fig. 8, A and B). The spatial distribution of p62 in these nuclear structures was different from its distribution in cytosolic inclusions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, 29% of the cells with colocalization contained nuclear p62 speckles closely adjacent but not directly overlapping with rounded spherical GFP-Ataxin1Q84 inclusions (Fig. 8C). In 35% of the cells, GFP-Ataxin1Q84 structures and p62 speckles overlapped in the form of recruitment of some of the GFP-Ataxin1Q84 protein into p62 speckles, resulting in elongated GFP-Ataxin1Q84 structures with one or two poles corresponding to p62 speckles (Fig. 8C). In the rest of the cells nuclear GFP-Ataxin1Q84 inclusions had an irregular shape with p62 antibody staining either surrounding the aggregates, forming a circle (in 13% of cells), or completely overlapping with GFP-Ataxin1Q84 aggregates (in 23% of cells) (Fig. 8C). On the other hand, the minor fraction of cells, containing cytoplasmic inclusions of GFP-Ataxin1, displayed a complete overlapping colocalization with p62 staining (data not shown). These observations suggest that p62 is specifically recruited to preformed nuclear aggregates of Ataxin1Q84 in a time-dependent manner, which is different from the co-aggregation type of recruitment of p62 to the cytosolic protein inclusions. Co-staining with anti-PML, anti-polyubiquitin, and anti-proteasomal antibodies revealed a high degree of colocalization of these proteins with Ataxin1Q84-recruited p62 (Fig. 8, B and C). Because p62 has been reported as a protein shuttling ubiquitinated proteins for proteasomal degradation (6), we decided to test if p62 can affect the recruitment of proteasomes to the nuclear inclusions containing Ataxin1Q84. Wild type MEFs or MEFs from p62−/− mouse (8) were transfected with GFP-Ataxin1Q84, fixed, and stained with anti-proteasome antibody 24 and 48 h after transfection. Surprisingly, 48 h after transfection only 39% of p62−/− MEFs showed a colocalization between GFP-Ataxin1Q84 and proteasomal staining, whereas in wild type MEFs, this colocalization was observed in 62% of the cells (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that p62 can facilitate the recruitment of proteasomes to the polyglutamine-expanded ataxin1 aggregates. To test whether p62 has any effect on the degradation of ataxin-1Q84, we generated HEK293 cells stably transfected with GFP-Ataxin1Q84 under the control of a Tet repressor-regulated CMV promoter. Knockdown of endogenous p62 with siRNA in these cells resulted in slower dynamics of clearance of GFP-Ataxin1Q84 after shutting down its synthesis by removal of tetracycline from the culture medium (Fig. 8, E and F). This observation suggests that p62 aids in the degradation of nuclear aggregates of Ataxin-1.

FIGURE 8.

p62 is recruited to Ataxin1Q84 nuclear protein inclusions and facilitated the recruitment of proteasomes to these structures. A, quantification is shown of colocalization between nuclear GFP-Ataxin1Q84 inclusions and endogenous p62 in HeLa cells 24 and 48 h after transfection. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the expression vector for GFP-Ataxin1Q84. 24 and 48 h after transfection cells were fixed, stained with antibodies against p62, and scored for colocalization between p62 and GFP-Ataxin1Q84. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment. B and C, confocal images are shown of HeLa cells transiently transfected with GFP-Ataxin1Q84, stained with antibodies against p62, PML, proteasome 20S core subunits, and polyubiquitin (polyUb) (FK1) 48 h after transfection. Scale bars equal 10 μm D, wild type (WT) or p62−/− MEFs were transiently transfected with the expression vector for GFP-Ataxin1Q84. 24 and 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed, stained with antibodies against the proteasome 20 S core subunits, and scored for colocalization between GFP-Ataxin1Q84 nuclear inclusions and proteasome staining by fluorescent microscopy. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of 3 independent experiments with more than 100 cells counted per experiment. E, HEK293 cells stably transfected with GFP-Ataxin1Q84 construct under the control of tet repressor-regulated CMV promoter were transfected with control (Ctrl.) siRNA or siRNA against p62, and the expression of GFP-Ataxin1Q84 was induced by tetracycline for 24 h. At 0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after removal of tetracycline, cells were lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies. F, shown is quantification of the rate of GFP-Ataxin1Q84 degradation from E. The levels of GFP-Ataxin1Q84 were normalized to actin. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. No ind., no induction.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrate that p62 is a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein. It contains two basic monopartite NLSs and a leucine-rich NES and is actively transported between both compartments at a high rate. The preferentially cytosolic distribution of p62 observed after immunostaining represents the steady state of the dynamic shuttling process and can be easily changed by even brief inhibition of nuclear protein export. Our data suggest that the nucleocytosolic distribution and/or transport of p62 are regulated by several mechanisms including self-interaction and polymerization, binding to ubiquitinated substrates, and phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues in the proximity of NLS2. Furthermore, p62 can recruit nuclear polyubiquitinated proteins or protein aggregates to PML bodies and may aid in their proteasomal degradation in the nucleus.

Our data indicate that polymerization of p62 reduces the rate of nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling, and this is presumably due to the large size of polymers and their tendency to aggregate. Although the diffuse cytosolic fraction of p62 quickly relocates to the nucleus, the punctuated cytosolic inclusions, containing aggregated polymers of p62, remain visible even after 30 min of LMB treatment. These p62 bodies disappear after 1 h of exportin-1 inhibition, but it is unclear whether this effect is due to nuclear import of p62 or its degradation by autophagy. Interestingly, the partially cytosolic localization of the diffuse fraction of the NES-deficient p62-(Δ303–320) mutant in HeLa cells (Fig. 2, C and E) suggests that even the diffuse cellular fraction of p62 consists mainly of polymers. Polymerization of p62 is essential both for efficient recognition of its ubiquitinated cargo (49) and for autophagic degradation of p62 itself (50). The isolated UBA domain of p62 has relatively low affinity for ubiquitin compared with other ubiquitin receptor proteins like Rad23 or NBR1 (49, 51), suggesting that multiple copies of the UBA domain of p62 in the polymer have to bind ubiquitinated cargo to achieve sufficient affinity. This is consistent with the function of p62 as an autophagic receptor that recognizes cargos containing multiple copies of monoubiquitin or polyubiquitin chains on their surface (for review, see Refs. 9 and 52).

The second factor that modulates the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of p62 is the level of intracellular ubiquitin, which likely acts by binding to the UBA domain of p62. The accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins or aggregates clearly has an anchoring effect on p62, resulting in its accumulation in aggregates in the cytosol or in the nucleus. However, because overexpression of the ubiquitin mutant defective in formation of three major types of polyubiquitin chains also inhibited nuclear import of p62, the possibility that ubiquitin binding directly affects the accessibility of NLS or its affinity for importin should not be excluded.

p62 is a phosphoprotein with serine-266, threonine-269, and serine-272 residues phosphorylated in a subpopulation of p62 molecules even in resting cells. The kinase(s) that mediates these phosphorylations is currently unknown. However, the Thr-269 and Ser-272 sites contain a proline residue in the +1 position, suggesting that proline-directed kinases of the mitogen-activated protein- or cyclin-dependent kinase families are likely candidates. Interestingly, ERK1/2 and p38 protein kinases have been described as binding partners of p62 (53, 54).

It is generally believed that attachment of an acidic phosphate group in proximity of the basic NLS should have a detrimental effect on the binding of karyopherins and nuclear import of the protein. Indeed, nuclear import of the phosphomimetic S266E mutant of p62 is strongly inhibited. In contrast, nuclear import of the phosphomimetic T269E and S272E mutants is accelerated. Because similar effects can be seen for the isolated NLS2 in p62-(247–287) and in full-length p62, it is likely that these phosphorylation events do not change the presentation of NLS2 by relieving some intramolecular inhibitory interactions but, rather, directly affect the affinity of NLS2 for importin. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of serine or threonine residues at the +2 or +3 position relative to the most C-terminal basic amino acid in monopartite NLSs has been shown to accelerate the nuclear import of at least two other proteins, BRCA1 and EBNA1 (55, 56). Comparison of nuclear localization signals from NLSdb (data base of nuclear localization signals) revealed that positions +2 or +3 relative to the last basic amino acid of NLS are commonly occupied by serine/threonine or acidic aspartate/glutamate residues (see supplemental Fig. 2). Previously published mutagenesis studies identified the importance of an acidic charge at the +2 position in a monopartite NLS, whereas the crystal structure of the NLS from c-Myc in complex with yeast karyopherin-α revealed the interaction of aspartate at +2 position with the indole ring of Trp-153 in the P7 pocket of karyopherin-α (57, 58). These data suggest that the addition of negative charge to serine or threonine at position +2 or +3 could be a general mechanism for positive regulation of monopartite NLSs.

Although the presence of p62 in nuclear protein aggregates has been demonstrated in several proteinopathies (22, 47, 48), very few studies have addressed the functional roles of nuclear p62. Our siRNA knockdown experiments suggest that p62 is essential for the recruitment of ubiquitinated proteins to the PML bodies after inhibition of protein export from the nucleus. Because we observed no change in electrophoretic mobility of p62 after LMB treatment, we can conclude that these ubiquitinated proteins represent the non-covalently bound cargo of the UBA domain and not the ubiquitinated form of p62 itself. There are numerous reports showing that many nuclear proteins have to be exported to the cytosol for efficient degradation. Tumor suppressor p53 is ubiquitinated and exported by the E3 ligase Mdm2 (59), whereas hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), an oncogenic transcription factor, is transported for degradation to the cytosol by von Hippel Lindau (VHL) protein, a substrate recognition component of the cullin-2 E3 ligase (60). Other examples of proteins exported to the cytosol for degradation are β-catenin (exported by adenomatous polyposis coli (61), Smad3 (exported by the ROC1-SCFFbw1a ubiquitin ligase complex), (62), p27Kip1 (exported by Jab1/CSN5) (63), cyclin D1 (64), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (65) (both proteins contain nuclear export signals). Thus, p62-mediated redistribution of ubiquitinated proteins to PML bodies after the inhibition of nuclear export is likely to represent an alternative mechanism for the degradation of these proteins in the nucleus. PML bodies have been proposed to function as sites of accumulation and degradation of misfolded proteins (30, 32). Because of its ability to interact with polyubiquitinated proteins and proteasomes, p62 may facilitate the degradation of these proteins. Our results suggesting that p62 is important for the recruitment of proteasomes to the nuclear inclusions of Ataxin1Q84 and that p62 contributes to their degradation may reflect such an adaptor role for p62. It is unclear, however, why cells utilize a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein like p62 instead of separate cytosolic and nuclear resident proteins for the recognition of ubiquitinated cargos by proteasomes. One possible explanation is that p62 also transports some components of the protein quality control or degradation systems from the cytosol to the nucleus. Alternatively, p62 can function as a sensor of nuclear and cytosolic proteotoxic stress, and sequestration of p62 in one of these compartments and the resulting depletion from the other could signal saturation of the ubiquitin-mediated degradation machinery in one of the compartments. We have previously shown that p62 is degraded by autophagy and acts as a cargo receptor for selective autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated proteins (7, 10). Hence, we cannot exclude a role of p62 in direct export of ubiquitinated substrates from the nucleus into the more degradation-potent cytosolic compartment. In conclusion, the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of p62 described in this paper opens up a new perspective suggestive of cooperation between nuclear and cytosolic protein quality control and degradation systems.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Brian Henderson and Huda Zoghbi for gifts of pRev1.4-GFP and pEGFP-C1-Ataxin1Q84, respectively. We thank Trine Nilsen and Anne Simonsen for the plasmids. We are indebted to Håvard Danielsen for the generous gift of tissue microarrays. We thank Lill Tove Busund and Lena M. Myreng Lyså for help with immunostaining of tissue microarrays and the BioImaging and Proteomics FUGE core facilities at the Medical Faculty for the use of instrumentation and expert assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Top Research Programme and the FUGE Programme of the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Cancer Society, and the Blix Foundation (to T. J.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- PB1

- Phox and Bem1p

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP

- LMB

- leptomycin B

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- ND10

- nuclear domain 10

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- NES

- nuclear export signal

- PML

- promyelocytic leukemia

- UBA

- ubiquitin-associated domain

- HIV

- human immunodeficiency virus

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joung I., Strominger J. L., Shin J. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 5991–5995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puls A., Schmidt S., Grawe F., Stabel S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6191–6196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanz L., Sanchez P., Lallena M. J., Diaz-Meco M. T., Moscat J. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 3044–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz L., Diaz-Meco M. T., Nakano H., Moscat J. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1576–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wooten M. W., Seibenhener M. L., Neidigh K. B., Vandenplas M. L. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4494–4504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seibenhener M. L., Babu J. R., Geetha T., Wong H. C., Krishna N. R., Wooten M. W. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8055–8068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjørkøy G., Lamark T., Brech A., Outzen H., Perander M., Overvatn A., Stenmark H., Johansen T. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 603–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komatsu M., Waguri S., Koike M., Sou Y. S., Ueno T., Hara T., Mizushima N., Iwata J., Ezaki J., Murata S., Hamazaki J., Nishito Y., Iemura S., Natsume T., Yanagawa T., Uwayama J., Warabi E., Yoshida H., Ishii T., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Yue Z., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Tanaka K. (2007) Cell. 131, 1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamark T., Kirkin V., Dikic I., Johansen T. (2009) Cell Cycle 8, 1986–1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pankiv S., Clausen T. H., Lamark T., Brech A., Bruun J. A., Outzen H., Øvervatn A., Bjørkøy G., Johansen T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24131–24145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin Z., Li Y., Pitti R., Lawrence D., Pham V. C., Lill J. R., Ashkenazi A. (2009) Cell 137, 721–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura H., Torigoe T., Asanuma H., Hisasue S. I., Suzuki K., Tsukamoto T., Satoh M., Sato N. (2006) Histopathology 48, 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolland P., Madjd Z., Durrant L., Ellis I. O., Layfield R., Spendlove I. (2007) Endocr. Relat. Cancer 14, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson H. G., Harris J. W., Wold B. J., Lin F., Brody J. P. (2003) Oncogene 22, 2322–2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duran A., Linares J. F., Galvez A. S., Wikenheiser K., Flores J. M., Diaz-Meco M. T., Moscat J. (2008) Cancer Cell. 13, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathew R., Karp C. M., Beaudoin B., Vuong N., Chen G., Chen H. Y., Bray K., Reddy A., Bhanot G., Gelinas C., Dipaola R. S., Karantza-Wadsworth V., White E. (2009) Cell. 137, 1062–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamark T., Perander M., Outzen H., Kristiansen K., Øvervatn A., Michaelsen E., Bjørkøy G., Johansen T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34568–34581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vadlamudi R. K., Joung I., Strominger J. L., Shin J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20235–20237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hocking L. J., Lucas G. J., Daroszewska A., Mangion J., Olavesen M., Cundy T., Nicholson G. C., Ward L., Bennett S. T., Wuyts W., Van Hul W., Ralston S. H. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2735–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurin N., Brown J. P., Morissette J., Raymond V. (2002) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1582–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii T., Yanagawa T., Yuki K., Kawane T., Yoshida H., Bannai S. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232, 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaoka U., Kim K., Jana N. R., Doi H., Maruyama M., Mitsui K., Oyama F., Nukina N. (2004) J. Neurochem. 91, 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zatloukal K., Stumptner C., Fuchsbichler A., Heid H., Schnoelzer M., Kenner L., Kleinert R., Prinz M., Aguzzi A., Denk H. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160, 255–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuusisto E., Kauppinen T., Alafuzoff I. (2008) Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 34, 169–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terry L. J., Shows E. B., Wente S. R. (2007) Science 318, 1412–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutay U., Güttinger S. (2005) Trends Cell Biol. 15, 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook A., Bono F., Jinek M., Conti E. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 647–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kvam E., Goldfarb D. S. (2007) Autophagy 3, 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rockel T. D., Stuhlmann D., von Mikecz A. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 5231–5242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lafarga M., Berciano M. T., Pena E., Mayo I., Castaño J. G., Bohmann D., Rodrigues J. P., Tavanez J. P., Carmo-Fonseca M. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2771–2782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janer A., Martin E., Muriel M. P., Latouche M., Fujigasaki H., Ruberg M., Brice A., Trottier Y., Sittler A. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen M., Singer L., Scharf A., von Mikecz A. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 180, 697–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao J., Diamond M. I. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, R115–R123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings C. J., Mancini M. A., Antalffy B., DeFranco D. B., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. (1996) Anal. Chem. 68, 850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson B. R., Eleftheriou A. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 256, 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.la Cour T., Gupta R., Rapacki K., Skriver K., Poulsen F. M., Brunak S. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 393–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsen T., Rosendal K. R., Sçrensen V., Wesche J., Olsnes S., Wiedùocha A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26245–26256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson M. I., Gill D. J., Perisic O., Quinn M. T., Williams R. L. (2003) Mol. Cell. 12, 39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer U., Huber J., Boelens W. C., Mattaj I. W., Lührmann R. (1995) Cell. 82, 475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallouzi I. E., Steitz J. A. (2001) Science 294, 1895–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanagawa T., Yuki K., Yoshida H., Bannai S., Ishii T. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 241, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nousiainen M., Silljé H. H., Sauer G., Nigg E. A., Körner R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5391–5396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olsen J. V., Blagoev B., Gnad F., Macek B., Kumar C., Mortensen P., Mann M. (2006) Cell. 127, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szeto J., Kaniuk N. A., Canadien V., Nisman R., Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Bazett-Jones D. P., Brumell J. H. (2006) Autophagy 2, 189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuusisto E., Parkkinen L., Alafuzoff I. (2003) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 62, 1241–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pikkarainen M., Hartikainen P., Alafuzoff I. (2008) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 67, 280–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirkin V., Lamark T., Sou Y. S., Bjørkøy G., Nunn J. L., Bruun J. A., Shvets E., McEwan D. G., Clausen T. H., Wild P., Bilusic I., Theurillat J. P., Øvervatn A., Ishii T., Elazar Z., Komatsu M., Dikic I., Johansen T. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ichimura Y., Kumanomidou T., Sou Y. S., Mizushima T., Ezaki J., Ueno T., Kominami E., Yamane T., Tanaka K., Komatsu M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22847–22857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raasi S., Varadan R., Fushman D., Pickart C. M. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirkin V., McEwan D. G., Novak I., Dikic I. (2009) Mol Cell. 34, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez A., Durán A., Selloum M., Champy M. F., Diez-Guerra F. J., Flores J. M., Serrano M., Auwerx J., Diaz-Meco M. T., Moscat J. (2006) Cell Metab. 3, 211–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sudo T., Maruyama M., Osada H. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 521–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hinton C. V., Fitzgerald L. D., Thompson M. E. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 1735–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitamura R., Sekimoto T., Ito S., Harada S., Yamagata H., Masai H., Yoneda Y., Yanagi K. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 1979–1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conti E., Kuriyan J. (2000) Structure 8, 329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makkerh J. P., Dingwall C., Laskey R. A. (1996) Curr. Biol. 6, 1025–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freedman D. A., Levine A. J. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 7288–7293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Groulx I., Lee S. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5319–5336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henderson B. R. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fukuchi M., Imamura T., Chiba T., Ebisawa T., Kawabata M., Tanaka K., Miyazono K. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1431–1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomoda K., Kubota Y., Kato J. (1999) Nature. 398, 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diehl J. A., Cheng M., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3499–3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davarinos N. A., Pollenz R. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28708–28715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thullberg M., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2000) Oncogene 19, 2870–2876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]