Abstract

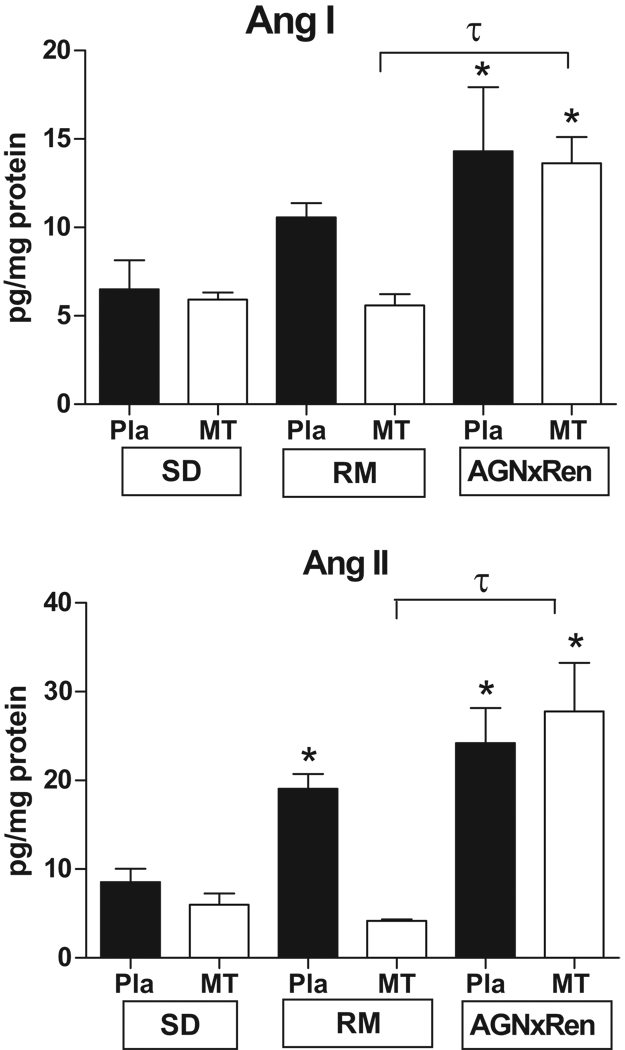

The pregnant female human angiotensinogen (hAGN) transgenic rat (TGR) mated with the male hrenin (hREN) TGR is a model of preeclampsia with increased blood pressure, proteinuria, and placenta alterations of edema and necrosis. The reverse mating (RM) of female hREN × male hAGN does not show preeclamptic features. Since the placenta is well recognized to be a key contributor to the preeclamptic syndrome, our hypothesis is that local angiotensin peptide concentrations found in the placenta (Pla) and its associated mesometrial triangle (MT) of the preeclamptic TGR differ from the RM. We characterized the Ang peptide content and the mRNA expression of hREN and hAGN of the MT and the Pla. Three groups of pregnant rats from the following matings [Sprague Dawley (SD) × SD, RM, and female hAGN × male hREN] were studied on day 21 of gestation. In the hAGNxhREN TGR Ang II is significantly increased in the Pla and MT vs SD (24.2 ± 3.9 vs 8.6 ± 1.5 pg/mg protein; 27.8 ± 5.5 vs 5.6 ± 1.3 pg/mg protein, p<0.05), whereas in the RM Ang II is increased in the Pla (19.1 ± 1.7 vs 5.6 ± 1.3 pg/mg protein, p<0.05) but unchanged in the MT (4.2 ± 0.2 vs 8.6 ± 1.5 pg/mg protein). The marked contrast in the expression of Ang II in the MT of the preeclamptic model vs the RM suggests that local Ang II generated from the maternal parts of the uteroplacental unit may play a critical role in preeclampsia.

Keywords: preeclampsia, renin-angiotensin system, angiotensinogen, placenta, fetal, maternal

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a common disease of pregnancy that is characterized by hypertension and proteinuria. The disease is generally thought to be associated with abnormal development of the placenta. However, interactions of the placenta and/or fetus with maternal factors are considered to contribute to the disease. Recent studies have identified strains of transgenic rats1 and mice2, mutant (p57Kip2-deficient)3 mice, and pre-existing borderline maternal hypertensive mice4 that show the classic features of preeclampsia, including hypertension, proteinuria, and kidney leisons. These models are important in demonstrating that maternal and feto-placental interactions can initiate this complex disease. However, the mechanisms may vary from pre-existing maternal condition, release and elevation of high levels of vasoconstrictors into the circulation arising from the placenta, or placenta pathology.

The pregnant female human angiotensinogen (hAGN) transgenic rat (TGR) mated with the male hrenin (hREN) TGR is a model of preeclampsia with increased blood pressure, proteinuria, and placenta alterations of edema and necrosis1. Their circulating levels of human plasma renin concentration (PRC) are elevated during pregnancy1, arising from hrenin released from the placenta. The reverse mating (RM) of female hREN TGR × male hAGN TGR does not show preeclamptic features. Dams harboring the hREN gene do not develop hypertension and proteinuria when they are mated with males with hAGN. Although hPRC is elevated during pregnancy, hAGN remained undetectable1, consistent with its not being released from the placenta. Part of the rationale for the difference in the two matings is the species specific dependency of renin and angiotensinogen for rodent and human proteins and their localization in the placenta and the circulation. Thus, single TGR with either hAGN or hREN are normotensive. When the female hAGN mates with the male hREN, active renin of placenta and/or of fetal origin is secreted and interacts with circulating hAGN in the dams to produce increased circulating Ang II. On the other hand, with the RM, hAGN remains undetectable in the circulation, indicating that it is not secreted from the placenta1 and the over production of Ang II in the circulation does not occur. Although the preeclamptic model is viewed as a high circulating Ang II model that arises from over-production of hrenin from the placenta, the function and regulation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in the uteroplacental unit is unknown.

The rodent has a haemochorial type of placenta which is apposed to a well-decidualized endometrium5. The placenta (Pla) consists of the labyrinth, trophospongium, and giant cell layers, which are of fetal origin. The labyrinth layer comprises the major portion of the placental disc, has very thin fetal capillaries surrounded by trophoblast cells, and constitutes the major site of maternal/fetal exchange. The trophospongium layer has uniform cells that are precursors of differentiated trophoblast cells. Associated with the placenta is the mesometrial triangle (MT) which consists of decidualized cells and numerous loops of spiral arteries. This area can be considered an expansion of the decidua or a deeper part of the placenta bed (maternal origin). Trophoblast invasion occurs in both the decidua and MT in the rat, a characteristic which Pijnenbort et al 6 propose makes it a suitable model for human pregnancy.

With the two types of TGR matings, the genetic composition of the uteroplacental unit may be quite different between tissues of fetal and maternal origin. A paternal expression of genes would be associated with fetal tissue and thus in the trangenic rats it is likely that both matings would express both the hAGN and hREN genes in fetal tissue. In the MT the genes of the dams would be present, however it is possible for the fetal genes to be present depending on the degree of invasion of the trophoblast cells, which are of fetal origin. Because the maternal influence may be critical in determining whether preeclampsia occurs, we characterized the Ang peptide content of the fetal (Pla) and maternal (MT) components of the utero-placental unit. Our objective was to determine if there is a difference in angiotensin peptide concentrations found in the MT and Pla of pregnant preeclamptic transgenic rats resulting from the mating of the female hAGN TGR mated with the male hREN as compared to the RM or normal SD pregnant rats.

The rationale and relevance for conducting studies in this animal model may reside in our recent demonstration showing that both the uterine maternal placenta bed7 and the chorionic villi8 of preeclamptic women had markedly elevated Ang II concentrations. This finding would suggest that activation of the RAS in both the maternal and fetal components of the utero-placenta unit may be important contributors to the human disease.

Methods

For these studies frozen tissue was received from the Drs. Dechend, Hering, and Herse from Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), Berlin, Germany. These tissues were obtained from animals described in previous publications1,9,10. Rat placentas with the attached MT were collected from a preeclamptic rat model [female TGR hAGN) × male TGR hREN] (n=4), the reverse mating (RM) [female TGR hREN × male TGR hAGN] (n=5) which did not show signs of preeclampsia, and age-matched control rats (Sprague-Dawly (SD × SD) (n=4) at day 21 of pregnancy 1,9,10. The MT and the proximal part of the mesometrium were dissected away from the placenta. Pla and MT were separated and snap frozen for mRNA and peptide measurements. For peptide measurements 4–5 MT and Pla from the same animal were pooled. Tissues were stored at −80°C until used. Local authorities (LAGeSo, Berlin, Germany) approved the animal protocol that complied with criteria outlined by the American Physiological Society.

Total mRNA was isolated with the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as described earlier11. Quality and quantity were checked by NanoDrop (Peqlab) and Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). 2µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit from Roche Diagnostics and were analyzed for hAGN, hREN, rAGN, rREN and 18S by realtime qPCR on ABI 5700 sequence detection system (PE Biosystems). Primer and probes were designed with PrimerExpress 2.0 (Applied Biosystems).

For Ang peptides analysis, tissue were homogenized in acid/ethanol [80% vol/vol 0.1N HCl] containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors including 0.44 mM 1,20 ortho-phenanthroline monohydrate, 0.12 mM pepstatin, 1 mM Na p-hydroxymercuribenzoate, 15% EDTA and 0.01 mM WFML-1, a rat renin inhibitor, centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4° C and stored overnight at 4°C, as previously described8,12. Samples were re-centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 20 min at 4° C and supernatant was removed and added to 1% HFBA and refrigerated overnight at −20° C. The supernatant was extracted using Sep-Pak columns activated with 5 ml wash of a mixture of n-heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA):methanol (0.1%:80%) and sequential washes of 0.1% HFBA. After the sample was applied to the column, it was washed with 0.1% HFBA and followed with a water wash. The sample was eluted with 3.3 ml washes of a mixture of acid methanol (0.1%:80%). The sample was eluted, reconstituted and split for two radioimmunoassays. Recoveries of radiolabeled Ang II were followed and samples were corrected for recoveries. Ang I was measured by a kit from Peninsula (San Carlos, CA) and Ang II by a kit from Alpco (Windham, NH). The minimum detectable levels of the assays were 1 and 0.8 fmol/ml for Ang I and Ang II, respectively. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 18% and 22% for Ang I and 8 and 22% for Ang II.

Data are presented as means ± SEM. We tested Kolmogorov-Smirnov for distribution. For group differences we tested one-way ANOVA with Scheffe post-hoc test, Dunnett-T3 or Kruskal-Wallis-Test and Mann-Whitney-U-Test as appropriate. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows that the preeclamptic model (hAGNxhREN) had significantly higher mean arterial blood pressure and albuminuria, and significantly lower fetal body weight and placenta weight as compared to the RM and SD pregnant rats. Figure 1 shows the levels of Ang I and Ang II in the MT and Pla of the three groups of pregnant rats. Ang I and Ang II levels were similar in the MT and Pla of the SD pregnant rat. In the preeclamptic model (hAGN × hREN), Ang II was significantly increased in both MT (24.2 ± 3.9 vs 8.6 ± 1.5 pg/mg protein, p<0.05) and Pla (27.8 ± 5.5 vs 5.6 ± 1.3 pg/mg protein, p<0.05) as compared to SD. In the RM, Ang II was increased in the Pla (19.1 ± 1.7 vs 5.6 ± 1.3 pg/mg protein, p<0.05) but unchanged in the MT (4.2 ± 0.2 vs 8.6 ± 1.5 pg/mg protein, ns). There was no difference between the levels of Ang II in the Pla between the preeclamptic and RM pregnant groups. A similar pattern was observed for Ang I (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Phenotype of animal models. g = grams, mg/d = milligrams/day. These data are in part previously published 1,9,10.

|

Pregnant Type |

SD | RM | hAGNxhREN |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAP (mmHg) | 94.7±3.8 | 84±3.8 | 141.4±9.4* |

| albuminuria (mg/d) | 0.22±0.07 | 0.31±0.1 | 15.15±6.7* |

| fetal-bodyweight (g) | 4.52±0.12 | 3.41±0.06 | 2.95±0.07* |

| placenta weight (with MT) (g) | 0.6±0.01 | 0.64±0.01 | 0.47±0.01* |

| fetal brain/liver-ratio | 0.53±0.02 | 0.55±0.02 | 0.74±0.03* |

Values are mean±SEM.

p<0.01 hAGNxhREN vs. SD and reverse mating (RM)

Figure 1.

Angiotensin peptides in the uteroplacental unit of normal pregnant (SD) and pregnant transgenics resulting from the mating of female hAGN × male hRen (preeclamptic model) and the reverse mating (RM). Ang I and Ang II are significantly increased in both the mesometrial triangle (MT) and placenta (Pla) in the preeclamptic model as compared to SD. In the RM, Ang II is increased in the Pla, but not the MT. Ang II is significantly higher in the MT of the preeclamptic vs the RM. Values are mean ± SEM.* p<0.05 vs SD. τ p<0.05 between groups as indicated.

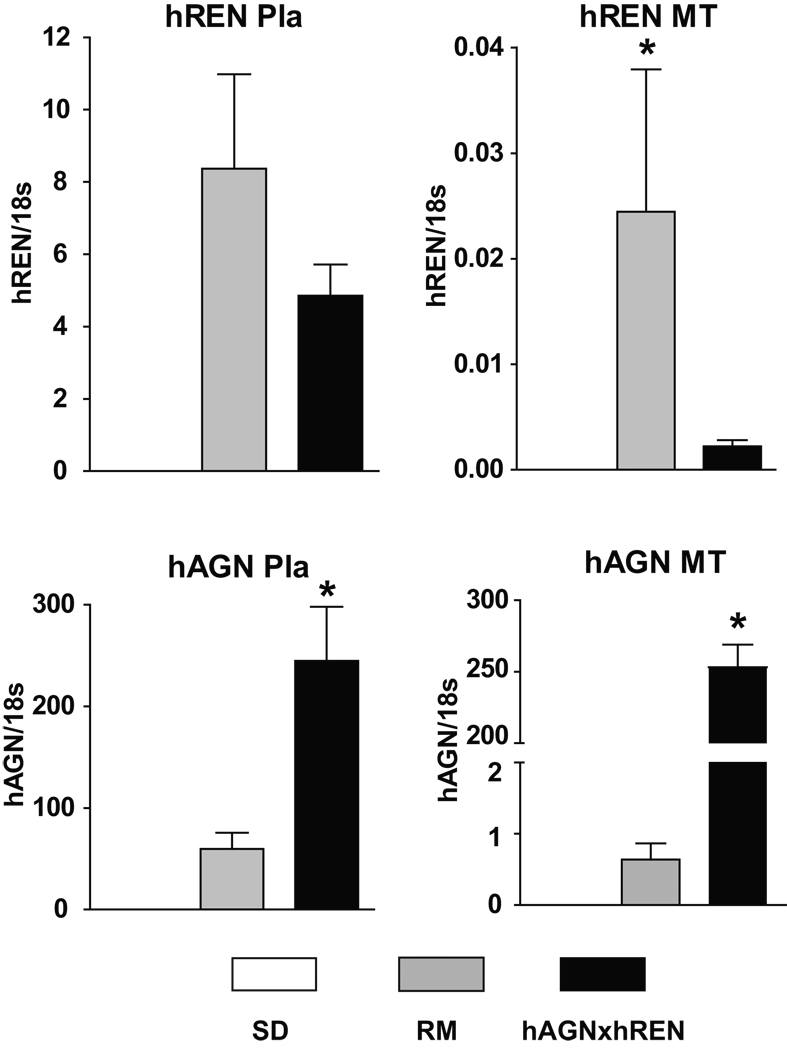

Figure 2 shows the expression of hREN and hAGN in the three groups of pregnant rats. As expected, hREN and hAGN mRNAs are not expressed in pregnant SD rats. The preeclamptic model and the RM have both hREN mRNA and hAGN mRNA in both the MT and Pla. However, the preeclamptic model has significantly higher levels of hAGN mRNA in the MT compared to the RM (>400-fold increase). The hREN mRNA in the MT is only weakly expressed compared to the Pla in both matings.

Figure 2.

Human renin (hREN) and angiotensinogen (hAGN) mRNA in the uteroplacental unit of normal pregnant (SD) and pregnant transgenics resulting from the mating of female hAGN × male hREN (preeclamptic model) and the reverse mating (RM). As expected, there is no hAGN or hREN mRNAs in SD placenta. In the preeclamptic model, both hREN and hAGN mRNAs are expressed in the MT and fetal Pla, although hREN mRNA shows a low level of expression in the MT. On the other hand, in the RM both mRNAs are expressed in the Pla, but hAGN is expressed at substantially lower levels in the MT compared to the preeclamptic model. Values are mean ± SEM. * p<0.01 between transgenic groups.

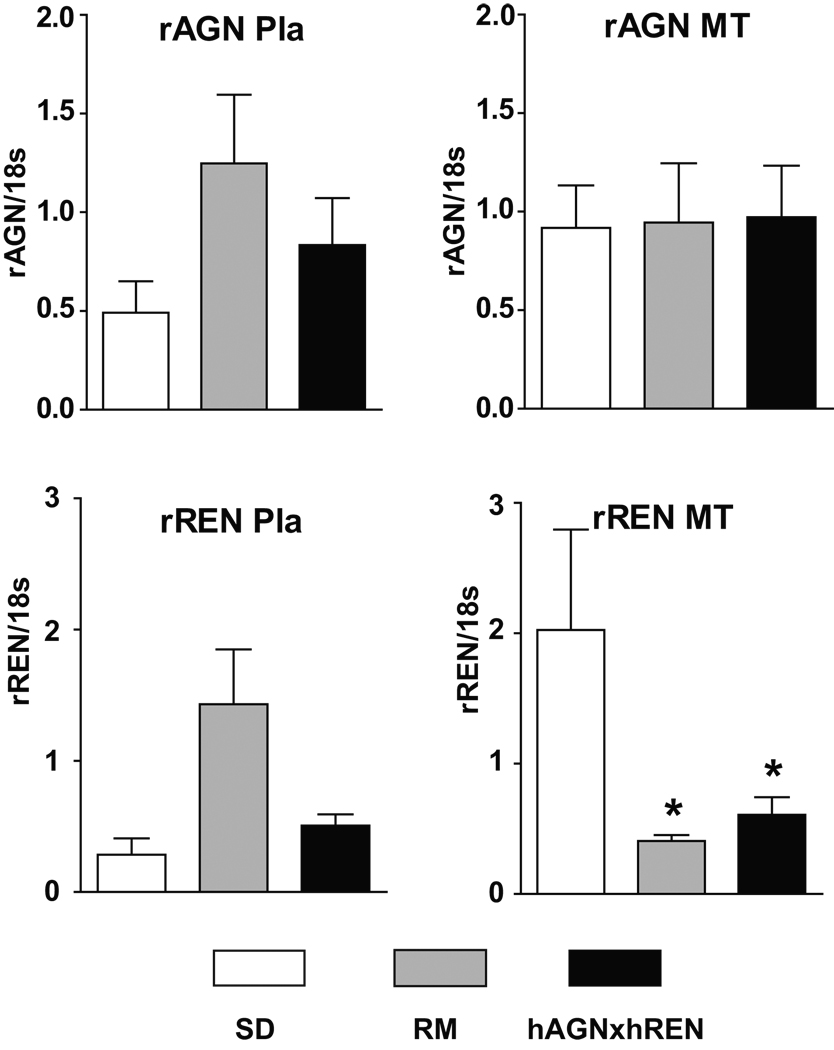

Figure 3 shows the expression of rREN and rAGN in the three groups of rats. The rREN mRNA and rAGN mRNA are expressed in all three groups and in both MT and Pla. In the preeclamptic model and in the RM, there was down-regulation of rREN mRNA in the MT as compared to SD.

Figure 3.

Rat renin (rREN) and angiotensinogen (rAGN) mRNA in the uteroplacental unit of normal pregnant and pregnant transgenics resulting from the mating of female hAGNx male hREN (preeclamptic model) and the reverse mating (RM). rREN and rAGN mRNAs are expressed in all three groups of pregnant animals at low levels. In the mesometrial triangle (MT), there is no change in rAGN, but significant down-regulation of rREN mRNA in both TGR pregnant rats. Values are mean ± SEM. * p<0.05 for groups vs SD.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that the Pla of both matings showed marked elevations in Ang II that arise from the expression of both hREN and hAGN mRNAs. The major finding of our study was the contrast in the expression of Ang II in the MT of the preeclamptic model vs the RM. In the MT from the preeclamptic TGR, Ang II was markedly elevated in association with the expression of both hREN and hAGN mRNA, whereas in the RM Ang II in the MT was not elevated, in association with substantially reduced expression of hAGN as compared to the preeclamptic mating. Our study provides evidence of two separate and differentially expressed local RAS in the MT and Pla. Because Ang II was elevated in the MT of the preeclamptic and not in the RM, the findings suggest that local actions of Ang II in the MT, influencing trophoblast invasion, survival and blood vessel remodeling, may be critical in contributing to the preeclamptic pathophysiology.

The very low expression of hAGN in the MT parallels the lack of detectable hAGN in the circulation of the RM1. In the RM, the endogenous hREN activity in the circulation was unaccompanied by hAGN protein, which was not released from the placenta into the maternal circulation. The lack of change of Ang II in the MT of the RM would suggest that hAGN from the Pla is also not released into the MT or transported in with the trophoblasts. On the other hand, in the preeclamptic TGR, plasma hREN concentration and circulating hAGN increased in late gestation, with the hREN arising from release from the placenta1. Our studies suggest that the renin is released from the Pla, because of the marked difference in expression of hREN in the Pla and MT. The placental origin of the hREN was also demonstrated in a similar transgenic mouse model showing that hREN is produced in trophoblast giant cells and secreted into the maternal circulation2. We confirmed that finding since the hREN expression is higher in the placenta (cellular types are of fetal origin) than in the MT (majority of cellular types are of maternal origin).

The MT consists of a mass of decidualized cells, uterine natural killer (NK) cells, and many loops of spiral arteries. In the rat, trophoblast cells from the placenta proliferate, migrate, and invade into the MT, the decidua, and the uterine vasculature 5. The fetal cells invade the maternal decidua and remodel the spiral arteries by replacing the endothelial layers of these vessels. The remodeled vessels promote an increase in blood flow, which promotes the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to the developing fetus. On the other hand, the long-held view is that preeclampsia arises from shallow trophoblast invasion and a reduced number of remodeled spiral arteries in the decidua, resulting in ischemia of the vessels13,14. Our findings in the MT must be assessed in light of a previous study characterizing endovascular trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling in the preeclamptic and RM transgenic rat models. Contrary to the hypothesis and evidence in human preeclampsia that there is restricted endovascular trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling in the myometrium, Geusens et al15 showed that the transgenic preeclamptic rats had deeper endovascular trophoblast invasion in the MT than the RM and SD controls. Because zygote-derived trophoblasts invade the MT, their presence in the MT would be consistent with the expression of both hREN and hAGN genes, reflecting both the maternal and paternal contribution to the augmented production of Ang II in both the MT and the Pla. The lower expression of hREN in the MT may not be a limiting factor in the production of Ang II, since it has been shown that renin protein can be released into the circulation from the placenta in these animals1. Furthermore, our finding of increased Ang II in the preeclamptic model in both the MT and Pla is consistent with our recent characterization of the RAS in human chorionic villi 8 and maternal placenta bed of preeclamptic subjects7, which demonstrated that Ang II was increased in both beds. The pattern of gene regulation contributing to the increased Ang II differed in the two local beds, with high AGN mRNA being found in the chorionic villi 8 and high REN mRNA being found in the maternal placenta bed7. Herse et al11 showed that components of tissue RAS are much higher in the maternal decidua than in the fetal parts of the placenta, suggesting a role for the RAS in trophoblast-decidua interaction. These latter findings, together with the differential expression in the MT and Pla of both TGR’s matings, support the presence of independent local RAS systems in fetal placenta and its associated maternal MT tissues.

With the reverse mating, Geusens et al15 showed that there were fewer trophoblasts present in the MT and that they invaded to a lesser degree as compared to the preeclamptic model. The findings of very low expression hREN and hAGN in the MT of the RM are consistent with the MT levels of Ang II that are not different from the control pregnant rats. In the MT of the RM, hAGN mRNA was 400-fold lower than in the preeclamptic model. A number of possibilities can be offered to explain the low levels of hAGN in the MT: 1) the fewer number of trophoblasts that invade resulted in lower levels of hAGN mRNA; or 2) there is down-regulation of hAGN gene expression in the MT of the reversible mating TGR. In both cases, the hAGN would not be sufficient to be translated into hAGN protein and thus could not interact with hrenin protein present in the maternal tissue to form Ang II. A third possibility is based on studies in a similar model of preeclampsia in transgenic mice conducted by Takimoto-Ohnishi and colleagues2 who showed using in situ hybridization that hREN is expressed in trophoblasts. This finding suggests that there may be cell type specific expression of hAGN and hREN. In the case of the RM, which has low maternal expression of hREN in the MT, if invading trophoblasts express only hREN there would be no additional Ang II generation because hAGN would not be provided by the fetal trophoblast cells.

In the Sprague Dawley pregnant rat, we showed that both the MT and the Pla express rREN and rAGN mRNAs; this was associated with equivalent amounts of Ang I and Ang II in both in parts of the placenta. As expected, there is no hREN or hAGN mRNA present. The most striking finding was the profound down-regulation of rREN mRNA in the MT in both TGR matings; and this occurred with no change in rAGN mRNA in the MT in both matings. Because blood pressure and the levels of Ang II are different in the MT of the preeclamptic and RM 1, it is not likely that either Ang II or blood pressure, two well-characterized regulators of renal renin 16, are responsible for the down-regulation of rREN in this tissue. To understand the regulation of the rREN mRNA in the MT, consideration of local cytokines, growth factors, or hormones released from or into the MT needs to be explored.

In conclusion, in the preeclamptic transgenic rat model there are two locally activated RAS in the placenta (fetal origin) and its associated maternal MT (maternal origin) due to the expression of hAGN and hREN in association with elevated Ang II. In the RM, the low level of expression hAGN and hREN in the MT is consistent with the low levels of Ang II. The contrast in the production of Ang II in the MT of the preeclamptic model vs the RM suggests a local action of the elevated Ang II in the MT that would influence trophoblast invasion and survival and the extent of blood vessel remodeling that may contribute to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia

Perspective

The placenta is a highly specialized organ that plays an essential role in fetal growth and development. The local placental RAS acts in an autocrine/paracrine way and is thought to be involved in increasing vascular permebility, angiogenesis, and decidualization during implantation and placental development17. This study highlights the distinctness of fetal and maternal utero-placental RAS components and the interactions that may arise in these local environments. In these transgenic models, the paternal influence was critical in determining the characteristics of the maternal environment. In the case of the preeclamptic model the paternal hREN gene was expressed in both the placenta and mesometrium triangle, resulting in an activated RAS in both. Theses findings are similar to the activation of local Ang II in fetal and maternal tissues of the uteroplacental unit in human preeclampsia7,8. Understanding the local maternal environment and its influence on the placenta appears to be critical in preeclampsia.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI-P01 HL51952 and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (DE631-1). The authors gratefully acknowledge grant support in part provided by Unifi, Inc. Greensboro, NC and Farley-Hudson Foundation, Jacksonville, NC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Bohlender J. Rats transgenic for human renin and human angiotensinogen as a model for gestational hypertension. J Am Soc Nephr. 2000;11:2056–2061. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takimoto E, Ishida J, Sugiyama F, Horiguchi H, Murakami K, Fukamizu A. Hypertension induced in pregnant mice by placental renin and maternal angiotensinogen. Science. 1996;274:995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanayama N, Takahashi K, Matsuura T, Sugimura M, Kobayashi T, Moniwa N, Tomita M, Nakayama Kl. Deficiency in p57Kip2 expression induces preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davisson RL, Hoffmann DS, Bust GM, Aldape G, Schlager G, Merrill DC, Sethi S, Weiss RM, Bates JN. Discovery of a spontaneous genetic mouse model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2002;39:337–342. doi: 10.1161/hy02t2.102904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caluwaerts S, Vercruysse L, Luyten C, Pijnenborg R. Endovascular trophoblast invasion and associated structural changes in uterine spiral arteries of the pregnant rat. Placenta. 2005;26:574–584. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pijnenborg R, Aplin JD, Ain R, Bevilacqua E, Bulmer JN, Cartwright J, Huppertz B, Knofler M, Maxwell C, Vercruysse L. Trophoblast and the endometrium-a workshop report. Placenta. 2004;25:S42–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.023. (Supplement A, Trophoblast Research 18) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anton L, Merrill DC, Neves LA, Diz DI, Corthrn J, Valdes G, Stovall K, Gallagher PE, Moorefield C, Gruver C, Brosnihan KB. The uterine placental bed renin-angiotensin system in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4316–4325. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anton L, Merrill DC, Neves LAAA, Stovall K, Gallagher PE, Diz DI, Moorefield C, Gruver C, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Activation of local chorionic villi angiotensin II levels but not angiotensin-(1–7) in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51:1066–1072. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dechend R, Gratze P, Wallukat G, Shagdarsuren E, Pleh R, Brasen JH, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Caluwaerts S, Vercruysse L, Pijnenborg R, Luft FC, Muller DN. Agonistic autoantibodies to the AT1 receptor in a transgenic rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005;45(part2):742–746. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154785.50570.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verlohren S, Neihoff M, Hering L, Geusens N, Herse F, Tintu AN, Plagemann A, LeNoble F, Pijnenborg R, Muller DN, Luft FC, Dudenhasuen JW, Gollasch M, Dechend R. Uterine vascular function in a transgenic preeclamptic rat model. Hypertension. 2008;5:547–553. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herse F, Dechend R, Harsem NK, Wallukat G, Janke J, Qadri F, Hering L, Muller DN, Luft FC, Staff AC. Dysregulation of the circulating and tissue-based renin-angiotensin system in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;49(part 2):604–611. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000257797.49289.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allred AJ, Chappell MC, Ferrario CM, Diz DI. Differential actions of renal ischemic injury on the intrarenal angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F636–F645. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.4.F636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Hanssens M. The uterine spiral arteries in human pregnancy:facts and controversies. Placenta. 2006;27:939–958. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geusens N, Verlohren S, Luyten C, Taube M, Hering L, Vercruysse L, Hanssens M, Dudenhausen JW, Pijnenborg Dechend R. Endovascular trophoblast invasion, spiral artery remodelling and uteroplacental haemodynamics in a transgenic rat model of pre-eclampsis. Placenta. 2008;29:614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall JE, Brands MW. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems-renal mechanisms and circulatory homeostasis. In: Seldin DW, Giebisch G, editors. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems. Chapter 40. New York: Raven Preses Ltd; 1992. pp. 1455–1504. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen AH, Schauser KH, Poulsen K. Current topic: the uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system. Placenta. 2000;21:468–477. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]