Abstract

Bacillus subtilis plasmid pBET131 is a derivative of pLS32, which was isolated from a natto strain of Bacillus subtilis. The DNA region in pBET131 that confers segregational stability contains an operon consisting of three genes, of which alfA, encoding an actin-like ATPase, and alfB are essential for plasmid stability. In this work, the alfB gene product and its target DNA region were studied in detail. Transcription of the alf operon initiated from a σA-type promoter was repressed by the alfB gene product. Overproduction of AlfA was inhibitory to cell growth, suggesting that the repression of the alf operon by AlfB is important for maintaining appropriate levels of AlfA. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay and footprinting analysis with purified His-tagged AlfB showed that it bound to a DNA region containing three tandem repeats of 8-bp AT-rich sequence (here designated parN), which partially overlaps the −35 sequence of the promoter. A sequence alteration in the first or third repeat did not affect the AlfB binding and plasmid stability, whereas that in the second repeat resulted in inhibition of these phenomena. The repression of alfA-lacZ expression was observed in the constructs carrying a mutation in either the first or third repeat, but not in the second repeat, indicating a correlation between plasmid stability, AlfB binding, and repression. It was also demonstrated by the yeast two-hybrid system that AlfA and AlfB interact with each other and among themselves. From these results, it was concluded that AlfB participates in partitioning pBET131 by forming a complex with AlfA and parN, the mode of which is typified by the type II partition mechanism.

Faithful distribution to daughter cells is essential for plasmids to be inherited in dividing cells, and this is achieved by mechanisms including active partitioning, postsegregational killing, and multimer resolution (15, 32). Low-copy-number plasmids are known to carry active partitioning mechanisms (17, 50), which are composed of a centromere-like site and two partitioning genes, one being an ATPase and the other a protein that binds to the centromere-like site. Active partitioning apparatuses can be classified into two types on the basis of the ATPase (13): type I, as exemplified by the Escherichia coli F and P1 plasmids, contains a Walker-type ATPase motif (4, 5, 7, 14, 18, 31), while type II, signified by E. coli R1, encodes an actin-like ATPase (11, 13, 22).

The three inheritance mechanisms have also been reported for Gram-positive bacteria. Multimer resolution systems, which effect random distribution of plasmid copies in the cell, have been reported for plasmids from Clostridium perfringens, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Enterococcus faecalis (12, 37, 43). With respect to the plasmid maintenance system classified as the killer-antidote system, several examples have been reported, including a restriction-modification system (24), a toxin-antitoxin system (53), and a determinant involving two small RNA molecules (49). Stability determinants involving the active partitioning mechanism have been reported for several plasmids from Gram-positive bacteria. Plasmids from Lactococcus lactis, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Enterococcus faecalis carry proteins with sequence similarities to the type I ATPases (8, 9, 10, 23, 36). The partition system encoded by a staphylococcal plasmid, pSK1, is unusual in that the parA gene product, which has no sequence similarity to known type I or type II ATPases, exerts the stabilization function without the involvement of other factors (41). Less well-characterized determinants involving a small DNA region and a protein, SpbA, have been reported for a plasmid from Bacillus thuringiensis (26). Another novel partition mechanism has been found recently, in which partitioning is executed by a tubulin-like protein (25).

In addition, a type II actin-like ATPase was found to be involved in partitioning a B. subtilis plasmid, pBET131, whose replication origin was derived from a B. subtilis (natto) plasmid, pLS32 (3, 45). pBET131, carrying 11 genes, including the replication origin region, is present in the cell at 1 to 2 copies per chromosome (46). It is less stable than pLS32 in both the original strain, B. subtilis (natto) IAM1163, and B. subtilis 168 (T. Tanaka, unpublished data), but much more stable than a pBET131 derivative lacking the plasmid stability region (3).

It was shown previously that the B. subtilis chromosome was dissected into two subgenomes when pBET131 was inserted into a DNA region in the chromosome surrounded by two homologous DNA sequences, but one of the subgenomes carrying the pBET131 origin, oriN, was rapidly lost or integrated into the other subgenome when only the oriN region was used, indicating the importance of the stability region for the stable maintenance of the oriN-driven subgenome (19, 20). Thus, in order to make oriN more useful for cloning purposes or genome analysis, it is useful to characterize the region conferring the segregational stability on oriN. Becker et al. have shown that two consecutive genes, alfA and alfB, on pBET131 confer segregational stability on the plasmid and that AlfA is an ATPase that forms actin-like filaments in B. subtilis cells (3). A partition mechanism that involves a putative actin-like protein has also been reported for the Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pSK41 (40). Since the partition involving type II ATPase is less well studied for plasmids of Gram-positive bacteria, it is of interest to characterize the partition mechanism of pBET131 and to compare the results with those for the Gram-negative counterparts. Recent studies of the AlfA structure and dynamics have shown that the AlfA filament is distinct from the ParM actin-like filament of plasmid R1 in that the former constitutes a more twisted helix and does not show dynamic instability (3, 35). It was also suggested by those authors that segregation by AlfA is significantly different from that exerted by ParM. In this report, I describe the characterization of the partition mechanism of pBET131 in vivo and in vitro by focusing on the functional characteristics of AlfB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction enzymes were purchased from Toyobo Co., Takara Co., and New England Biolabs. T4 DNA ligase was from New England Biolabs. DNase I and T4 DNA polymerase were purchased from Takara Co. and Roche, respectively. Synthetic oligonucleotides were commercially prepared by Tsukuba Oligo Service Co. and are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. NuSieve 3:1 agarose was from Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Inc. Matchmaker GAL4 Two-hybrid System 3, yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium, minimal Synthetic Dropout (SD) base, and Dropout (DO) supplements lacking Leu/Trp or Ade/His/Leu/Trp were purchased from Clontech. Protein molecular mass markers (2,500 to 17,000 Da) were obtained from Sigma.

Bacterial strains, and strain construction.

The bacterial and yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The strains carrying the alfA-lacZ fusions were constructed by linearization of plasmid pOF5LA2 with ScaI, followed by insertion into the amyE locus of strain CU741.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | ||

| CU741 | trpC2 leuC7 | 48 |

| LA213 | trpC2 leuC7 amyE::alfA-lacZ (Cmr) | pOF5LA2 × CU741 |

| WILA2 | LA213 derivative with alfA preceded by synthetic, wild-type repeat sequences | pWILA2 × CU741 |

| LMLA2 | WILA2 derivative carrying an alteration in the first repeat | pLMLA2 × CU741 |

| MDLA13 | WILA2 derivative carrying alterations in the first and second repeats | pMDLA13 × CU741 |

| RMLA11 | WILA2 derivative carrying an alteration in the third repeat | pRMLA1 × CU741 |

| E. coli | ||

| JM103 | Δlac-pro thi rpsL supE sbcB hsdR4 F′ [traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | 51 |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| AH109 | MATatrpl-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 ga14 Δgal80 ΔLYS2:: GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3 GAL2]UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2 URA3::MEL1UAS-MEL1TATA-lacZ | Clontech |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDH88 | Integration vector carrying Pspac promoter | 16 |

| pDG148 | Carries Pspac promoter before muticloning sites | 42 |

| pQE8 | Expression vector for construction of His-tagged proteins | Qiagen |

| pIS284 | Delivers promoter-E. coli lacZ fusion to B. subtilis amyE locus and carries EcoRI, BamHI and XbaI sites in that order upstream of the lacZ gene | I. Smith |

| pBET131 | Wild-type plasmid (Fig. 1A) | 46 |

| pBIF2965 | pBET131 carrying a deletion from the BamHI site to position 2964 | This study |

| pBIC6561 | pBIF6561 carrying Pspac promoter upstream of position 2965 | This study |

| pBIF6561 | pBIF2965 carrying a deletion spanning positions 3033 to 3060 | This study |

| pBIAW2 | pBET131 carrying synthetic, wild-type DNA between BamHI and SnaBI sites | This study |

| pBIBM6 | pBET131 carrying a deletion between the BamHI and SnaBI sites | This study |

| pBIBM19 | pBIAW2 carrying nucleotide alterations in the first repeat | This study |

| pBIBM24 | pBIAW2 carrying nucleotide alterations in the second repeat | This study |

| pBIBM34 | pBIAW2 carrying nucleotide alterations in the third repeat | This study |

| pBIBM8 | pBIAW2 carrying nucleotide alterations in both the first and second repeats | This study |

| pDGEN51 | pDG148 carrying alfA downstream of Pspac promoter | This study |

| pENSA51 | pDGEN51 carrying a blunt-ended SacI site in alfA | This study |

| pDGEX561 | pDG148 carrying alfA and alfB downstream of Pspac promoter | This study |

| pEXSA564 | pDGEX561 carrying a blunt-ended SacI site in alfA | This study |

| pOF5LA2 | pIS284 carrying the promoter region of alfA before lacZ | This study |

| pWILA2 | pORF5LA2 derivative carrying synthetic, wild-type repeat sequences | This study |

| pLMLA2 | pWILA2 derivative carrying an alteration in the first repeat | This study |

| pMDLA13 | pWILA2 derivative carrying alterations in the first two repeat sequences | This study |

| pRMLA1 | pWILA2 derivative carrying an alteration in the third repeat | This study |

| pQE8OF6 | pQE8 carrying alfB | This study |

| pGBKT7 | Kmr; cloning vector carrying GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD) | Clontech |

| pGADT7 | Ampr; cloning vector carrying GAL4 activation domain (AD) | Clontech |

| pGBA3 | pGBKT7 carying a fusion between alfA and GAL4 DNA BD | This study |

| pGAB142 | pGADT7 carrying a fusion between alfB and GAL4 AD | This study |

| pGB64 | pGBKT7 carrying a fusion between alfB and GAL4 DNA BD | This study |

| pGA51 | pGADT7 carrying a fusion between alfA and GAL4 AD | This study |

| pGBKT7-53 | Carrying a fusion between murine p53 and GAL4 DNA BD in pGBKT7 | Clontech |

| pGADT7-T | Carrying a fusion between simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen and GAL4 AD in pGADT7 | Clontech |

Medium and antibiotics.

Schaeffer sporulation (39) and Luria-Bertani (LB) media were used for growing Bacillus subtilis and both E. coli and B. subtilis strains, respectively. Chloramphenicol (Cm), tetracycline (Tc), and neomycin (Nm) were added at concentrations of 5 μg/ml, 10 μg/ml, and 15 μg/ml, respectively. Ampicillin (Ap) was added at 100 μg/ml for E. coli culture. YPD medium supplemented with 0.2% adenine hemisulfate was used for growing the yeast strain AH109. For the selection of AH109 transformants, the SD minimal medium with either the −Leu/−Trp DO supplement or the −Ade/−His/−Leu/−Trp DO supplement added was used. X-α-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside) was added at a concentration of 80 μg/ml. The media for growing yeast were prepared according to the procedure recommended by Clontec.

Construction of plasmids.

The procedures to construct the plasmids used in this study are described in the supplemental material.

Primer extension analysis.

Primer extension was performed with an AMV RT cDNA Synthesis Kit obtained from Takara Co. The reaction mixture contained 10 μg of RNA and a primer, ORF5Bio3, biotinylated at the 5′ end. The reaction product was run in a sequencing gel, together with sequencing ladders prepared by using the same primer with pBET131 as a template. RNA was isolated as described previously (52).

β-Galactosidase activities.

Cells were grown overnight in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics, and the culture medium (50 μl) was transferred to 50 ml of Schaeffer sporulation medium containing the same antibiotics. IPTG (isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside) was added at a concentration of 0.1 mM to the Schaeffer medium when necessary. Samples (1 ml) were withdrawn from T-1 (1 h before the end of the exponential growth phase) or T1 (1 h after the end of the exponential growth phase) to T4, and the cells were collected by centrifugation. β-Galactosidase activities were measured as described previously (33).

Purification of histidine (His)-tagged AlfB.

E. coli JM103 carrying pQEORF6 was grown overnight in LB medium containing Ap, and the culture medium was transferred to the same fresh medium at a concentration of 1%. After the cell density reached 70 Klett units (red filter), IPTG was added at a final concentration of 2 mM. His-tagged AlfB protein was purified by a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid silica column as described previously (44).

Binding of His-tagged AlfB protein to DNA.

Binding of His-tagged AlfB to DNA and subsequent analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis were performed by a method described previously (44). The reaction mixture contained 15 to 20 ng of 290-bp DNA fragments to be tested, 170 ng of RsaI fragments of pUC19 (51), and various amounts of His-tagged AlfB. The reaction mixtures were left at room temperature for 40 min and then directly added to the wells formed in 3.5% NuSieve 3:1 agarose for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

DNase I footprinting.

PCR fragments from positions 2871 to 3330 and from positions 3131 to 2700, which were biotin labeled at the 5′ ends, were prepared by using primers 2871Bio plus BET3330R (for the nontemplate strand) and 3131Bio plus 2700F (for the template strand), respectively. Sequencing ladders were prepared by using the same biotinylated primers with the plasmid pBET131 as a template. The binding reaction was performed as described above in a total volume of 40 μl at room temperature for 40 min, followed by the addition of 3.5 μl of 10×-concentrated DNase I buffer (Roche) and 1.4 μl of DNase I (1 unit/ml). After the reaction mixture had been incubated at 37°C for 2 min, the DNase I-treated DNAs were prepared for gel electrophoresis by the procedure described by Tsukahara and Ogura (47).

Segregational stability of plasmids.

The constructed plasmids in E. coli JM103 were transformed into strain CU741, and the plasmid stability was determined as follows. Cells grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium containing Cm and Tc were inoculated into LB medium without the antibiotics and grown for 10 generations. The cells before and after incubation were spread on LB plates without the antibiotics and incubated overnight. Of the colonies formed, 150 to 200 were picked and examined for resistance to both Cm and Tc by toothpick transfer onto LB plates with or without the antibiotics.

Yeast two-hybrid system.

The Matchmaker GAL4 Two-hybrid System 3 obtained from Clontech was used for testing protein-protein interactions. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 was made competent and transformed with plasmids as described in the Clontech manual.

RESULTS

The plasmid stability region in pBET131.

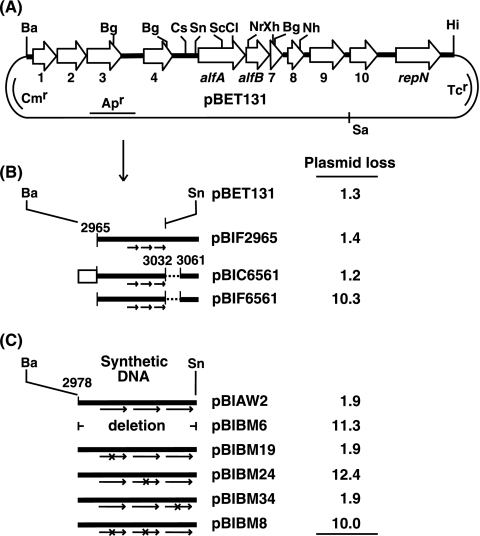

Becker et al. have reported that among the 11 open reading frames of pBET131 (Fig. 1A), only the alfA and alfB genes are required for the maintenance of the plasmid (3), and these results have been confirmed (Tanaka, unpublished). The open reading frames alfA, alfB, and orf7 apparently constitute an operon, since the last codons of alfA (275 codons) and alfB (93 codons) overlap the initiation codons of alfB and orf7 (51 codons), respectively (46).

FIG. 1.

Localization of the DNA region responsible for the segregational stability of pBET131. Plasmid stability was determined as described in Materials and Methods and is shown as percent plasmid loss per generation. (A) Restriction map of pBET131. The DNA region between the BamHI and HindIII sites was derived from pLS32 (46). The open arrows show the open reading frames on pBET131. Abbreviations: Ba, BamHI; Bg, BglII; Cl, ClaI; Cs, Csp45I; Hi, HindIII; Nh, NheI; Nr, NruI; Sa, SalI; Sc, SacI; Sn, SnaBI; Xh, XhoI. (B) Derivatives of pBET131 carrying modifications in the upstream region of alfA. The rectangle and the dotted lines show the Pspac promoter and the deleted region between positions 3033 and 3060, which contains part of the promoter for the alf operon (Fig. 2B), respectively. The three arrows depict the tandem repeat sequence located between positions 3000 and 3031. (C) Derivatives of pBET131 carrying synthetic 55-nucleotide sequences between the BamHI and SnaBI (position 3032) sites of pBET131. The arrows and ×s show the tandem repeats and nucleotide changes, respectively.

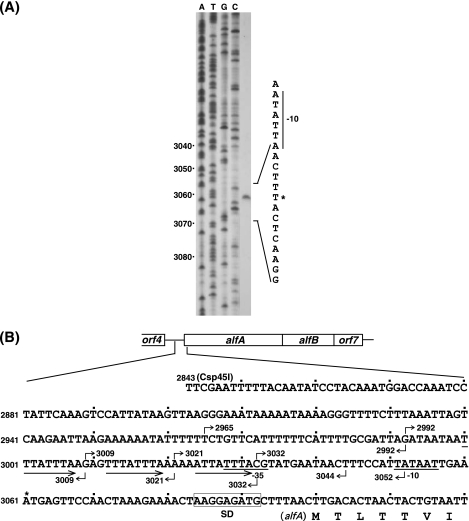

Transcription initiation site of the alf operon.

As part of the characterization of the control region of the alf operon, we first determined the transcription initiation site. RNA was isolated from the CU741 cells carrying pBET131 and used as the template for a reverse transcriptase reaction. It was shown that the transcription starts at position 3061 (Fig. 2A), which is 39 nucleotides upstream of the initiation codon of alfA (Fig. 2B). Putative −35 (TTTACG) and −10 (TATAAT) regions, which are likely to be recognized by σA RNA polymerase, were identified upstream of the transcription initiation site (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Determination of the transcriptional start site of the alf operon. (A) Primer extension analysis. The transcriptional start point and the putative −10 sequence are shown by the asterisk and bar, respectively. The numbers on the left show the coordinates starting from the BamHI site of pBET131 (Fig. 1A) (46). (B) The nucleotide sequence starting from the Csp45I site (position 2843) to the 7th codon of alfA on pBET131. The numbers with the bent arrows above and below the sequence show the 5′ and 3′ ends of the DNA fragments, respectively, that were used for gel shift analysis. The three arrows, bars, and rectangle depict the tandem repeats and promoter and Shine-Dalgarno sequences, respectively.

Confinement of the DNA region responsible for plasmid stability.

The E. coli plasmids, such as F, P1, and R1, carry a cis sequence with which one of the par proteins interacts (4, 6, 10, 15, 50). In an attempt to narrow down the cis DNA region necessary for the stable maintenance of pBET131 (Fig. 1A), three plasmids carrying deletions upstream of alfA were constructed. Plasmid pBIF2965 is a derivative of pBET131 carrying a deletion from the BamHI site to position 2964, while pBIF6561 is a derivative of pBIF2965 carrying a deletion from positions 3033 to 3060, where most of the promoter region for the alf operon is located (Fig. 1B and 2B). Plasmid pBIC6561 carries the Pspac promoter (16) upstream of position 2965 of pBIF6561. It was shown that pBIC2965, but not pBIF6561, was as stable as pBET131 (Fig. 1B). These results show that the region upstream of position 2965 is not required for plasmid stability and that the promoter for the alf operon is necessary, as expected. When the Pspac promoter was placed upstream of position 2965 of pBIF6561, the resultant plasmid, pBIC6561 (Fig. 1B), became stable, indicating that the DNA region between positions 2965 and 3032 is sufficient to stabilize the plasmid, as long as the alf operon is transcribed.

To further investigate the DNA sequence necessary for plasmid stability, the region between the BamHI and SnaBI (position 3032) sites of pBET131 was replaced with a synthetic sequence spanning positions 2978 to 3032 (Fig. 1C and 2B). The resultant plasmid, pBIAW2, showed stability similar to the level exhibited by pBET131 (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, pBIBM6, lacking the synthetic DNA, was found to be unstable (Fig. 1C), indicating the importance of this DNA region. It was noted that the region contains three tandem repeats with a consensus sequence, 5′-T(A)TTATTTA-3′, which are separated from each other by 4 nucleotides (Fig. 2B). To examine whether the repeats are involved in plasmid stability, the nucleotide sequences of the repeats were changed and the segregational stability of the resultant plasmids was examined. The results showed that the stability was not affected when the first repeat was changed to the sequence 5′-ATATATAT-3′ (pBIBM19), while the same sequence change in the second repeat resulted in plasmid instability (pBIBM24) (Fig. 1C). The nucleotide alterations in both the first and second repeats by the same sequence caused instability of the plasmid (pBIBM8), as expected, and the mutation in the third repeat from 5′-ATTATTTA-3′ to 5′-TAATTTGA-3′ did not affect plasmid stability (pBIBM34) (Fig. 1C). These results can be interpreted to indicate that either two consecutive repeats have to be present adjacently or the second repeat alone is sufficient for the stable maintenance of pBET131. However, since the sequences of the first and second repeats are the same and the presence of this sequence was not sufficient to stabilize the plasmid (pBIBM24), it is unlikely that the second repeat alone provides the stability function.

The existence of A-T tracts in the repeat region suggested static bending of DNA, but no such bent DNA was observed, as shown by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis run at both low and high temperatures (34; T. Tanaka, data not shown).

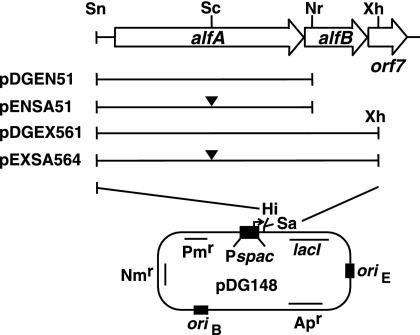

Repression of alf operon expression by AlfB.

Becker et al. showed that deletion of alfB resulted in inhibition of cell growth (3). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that excessive levels of AlfA are detrimental to cell growth and that the expression of alfA may be controlled by AlfB. To test these possibilities, the alfA gene alone or both the alfA and alfB genes were placed downstream of the IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter carried on pDG148 (42), resulting in plasmids pDGEN51 and pDGEX561, respectively (Fig. 3; see the supplemental material). In addition, the SacI site in alfA (Fig. 1A) was filled with DNA polymerase and ligated to disrupt the alfA gene in the two plasmids, resulting in pENSA51 and pEXSA564, respectively (Fig. 3). In these constructs, the 5′ terminus of the cloned DNA region is the SnaBI site located at position 3033 within the −35 region (Fig. 1A and 2B), and thus, the expression of the downstream genes solely depends on the Pspac promoter. When the promoter was activated by the addition of IPTG (0.05 mM), the host cells carrying pDG51 or pDGEX561, but not pENSA51 or pEXSA564, failed to form colonies on Nm-containing plates (T. Tanaka, data not shown), indicating that overproduced AlfA leads to growth inhibition irrespective of the presence or absence of AlfB.

FIG. 3.

Derivatives of pDG148 carrying alfA and alfB downstream of the IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter. The solid bars depict the DNA regions carried in the plasmids. The filled triangles show the SacI sites that were blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase and ligated. For the abbreviations of the restriction enzymes, see the legend to Fig. 1. oriB, replication origin for B. subtilis; oriE, replication origin for E. coli.

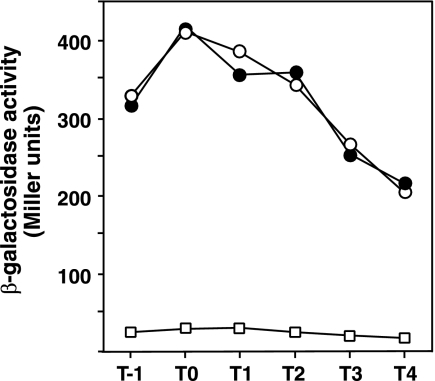

Next, the expression of alfA was examined. The DNA region between the BglII site in orf4 and the SacI site in alfA (Fig. 1A), which contains the upstream region of alfA and its N-terminal region, was inserted before the promoterless E. coli lacZ gene in pIS284, and the resultant alfA-lacZ fusion was placed at the amyE locus of CU741 (strain LA213). The expression levels of alfA-lacZ were quantified in the cells carrying pENSA51, pEXSA564, and their vector pDG148. It was found that the expression of alfA-lacZ was unaffected by overexpression of truncated alfA (pENSA51) compared to the control level exhibited by the pDG148-containing cells, whereas it was greatly reduced by overexpression of alfB on pEXSA564 (Fig. 4). It should be noted that alfA-lacZ expression was not affected by overexpression of alfA, as shown by using pDGEN51 under conditions where the concentration of IPTG added had little growth effect on the host strain (T. Tanaka, data not shown). These results show that AlfB works as a repressor of the alf operon.

FIG. 4.

Repression of alfA expression by AlfB. The cells of strain LA213 (amyE::alfA-lacZ) carrying the plasmids were cultured in the presence of Cm, Nm, and IPTG, and the β-galactosidase activities were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The structures of the plasmids are shown in Fig. 3. ○, pDG148; •, pENSA51; □, pEXSA564.

Binding of AlfB to the upstream region of the alfA promoter.

The repressor activity of the AlfB protein suggested that it might bind to a specific region upstream of alfA. To test this possibility, the AlfB protein histidine tagged at the N terminus was prepared (Fig. 5A) and used for gel shift analysis. A series of DNA fragments of 290 to 298 bp, referred to as the “290-bp” fragment, starting from positions 2965, 2992, 3009, 3021, and 3032 (Fig. 5B and 2B) were prepared by PCR and incubated with the His-tagged AlfB protein. To this reaction mixture were added three RsaI-digested pUC19 fragments, which served as internal controls for testing nonspecific DNA binding to the AlfB protein. Under conditions where there was little effect on the mobility of the pUC19-derived DNA bands (shown by the dots in Fig. 5B), band shifting was observed for the 290-bp fragments, starting from positions 2965, 2992, and 3009 (Fig. 5B, a, b, and c), whereas no shifted band was observed for those starting from positions 3021 and 3032 (Fig. 5B, d and e), indicating that the 5′ boundary of the AlfB binding site exists downstream of position 3009. Similarly, the 3′ boundary of the binding region was examined using the 290-bp fragments ending at positions 2992, 3009, 3021, 3032, 3044, and 3052. The results showed that shifted bands were seen for the fragments carrying the 3′ termini at positions 3021, 3032, 3044, and 3052 (Fig. 5B, h, i, j, and k), indicating that the 3′ boundary is located upstream of position 3021. It was noted that in both experiments the 290-bp DNA fragments contained two adjacent repeats in the cases where DNA binding by AlfB was observed.

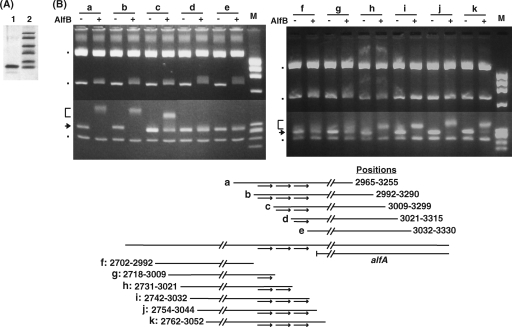

FIG. 5.

Purification of His-tagged AlfB (A) and determination of the 5′ (left) and 3′ (right) boundaries of the AlfB binding site by using EMSA on fragments bearing various deletions upstream of alfA (B). (A) SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of His-tagged AlfB. Lanes: 1, purified sample; 2, molecular mass markers (from the top in Da, 16,950, 14,440, 10,600, 8,160, 6,210, and 2,520). (B) The 290-bp fragments used are shown below (Fig. 2B shows exact positions). The arrows and brackets on the left indicate the 290-bp DNA fragments at their original and shifted positions, respectively. The other three DNA bands, indicated by the dots, are the RsaI fragments of pUC19 (from the top in bp, 1,769, 676, and 241). + and − show the presence and absence of His-tagged AlfB in the reaction mixture. The HaeIII fragments of φX174 DNA were run as size markers (M). The arrows in the scheme depict the tandem repeat sequences. The reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods, except that 0.3 μg of His-tagged AlfB was used. The DNA fragments were prepared by using the PCR primers (shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material) as follows: a, BET2965F and BET3255R; b, BET2992F and BET3290R; c, BET3009F and BET3299R; d, BET3021F and BET3315R; e, BET3032F and BET3330R; f, BET2702F and BET2992R; g, BET2718F and BET3009R; h, BET2731F and BET3021R; i, BET2742F and BET3032R; j, BET2754F and BET3044R; k, BET2762F and BET3052R.

Footprinting analysis.

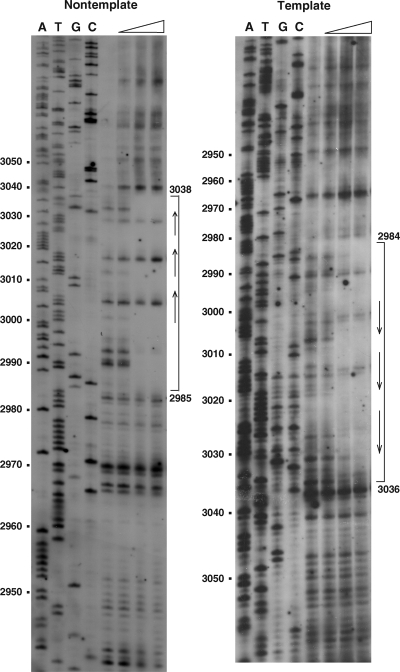

To gain more insight into the binding site of AlfB, DNase I footprinting was performed. It was shown that the DNA region spanning positions 2985 to 3038 was protected from DNase I digestion in the nontemplate strand, whereas the region from positions 2984 to 3036 was protected in the template strand (Fig. 6). The three tandem repeats are within the protected region, and the −35 sequence of the alf promoter resides in the 3′ end of this DNA region (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 6.

DNase I footprinting analysis of the binding region of His-tagged AlfB. DNA fragments labeled with biotin at either position 2871 (left) or position 3131 (right) were subjected to footprinting analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The open triangles show the increase of His-tagged AlfB (from left to right, 0, 0.3, 0.9, and 2.7 μg). The reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods. The arrows and brackets denote the tandem repeats and the protected regions from DNase I, respectively. The numbers on the left show the nucleotide positions from the BamHI site of pBET131 (Fig. 1A and 2B).

Involvement of tandem repeat sequences in the binding of AlfB.

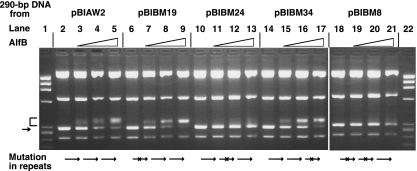

To further investigate the nature of the binding of AlfB to the upstream region of alfA, we tested AlfB binding to the 290-bp fragments spanning positions 2979 to 3263, which carry wild-type or altered sequences in the repeats. The PCR fragments were prepared by using wild-type pBIAW2 and its mutants pBIBM19, pBIBM24, pBIBM34, and pBIBM8 (Fig. 1C) as the templates. The results shown in Fig. 7 indicate that as the concentration of AlfB was increased, the intensities of the shifted bands increased for the DNA fragments derived from the stable plasmids pBIAW2, pBIBM19, and pBIBM34, which carry wild-type repeats and sequence alterations in the first and third repeat, respectively, whereas no band shifting was observed for those derived from the unstable plasmids pBIBM24 and pBIBM8 carrying alterations in the second repeat and both the first and second repeats, respectively.

FIG. 7.

Binding of His-tagged AlfB to the 290-bp wild-type and mutant DNA fragments containing the tandem repeat region. Various 290-bp DNA fragments were prepared using primers PBR358 and 3263R2 and the plasmids pBIBW2, pBIBM19, pBIBM24, pBIBM34, and pBIBM8 as the templates. The reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods, except that the reaction mixture contained 0 μg (lanes 2, 6, 10, 14, and 18), 0.1 μg (lanes 3, 7, 11, 15, and 19), 0.2 μg (lanes 4, 8,12,16, and 20), and 0.3 μg (lanes 5, 9, 13, 17, and 22) of His-tagged AlfB. Lanes 1 and 22, size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 DNA). The arrow and bracket on the left indicate the 290-bp DNA fragments at their original and shifted positions, respectively.

The results with pBIBM24 show that AlfB is unable to bind the 290-bp fragment if the DNA region carries the sequence alteration in the middle of the three consecutive repeats, indicating that neither the individual single repeat at the first or third position nor the presence of two repeats with the middle repeat carrying the sequence alteration supports AlfB binding. This is in accordance with the finding that two repeats were present consecutively when AlfB bound to the 290-bp fragment successfully (Fig. 5). Another possibility remains unaccounted for in these data: that the binding requires only the second repeat. However, since the first and second repeats share the same sequence (Fig. 2B) and the first repeat alone or together with the third repeat could not support AlfB binding, as described above, this possibility may be ruled out.

Hereafter, the region containing the three tandem repeats is designated parN.

Requirement for the tandem sequences in AlfB repression.

I next investigated whether the three tandem repeats are necessary for repression of the alf operon. To do this, alfA-lacZ fusions were constructed in which the three tandem repeat sequences were altered: strain WILA2 carried the wild-type sequence, whereas strains LMLA2, MDLA13, and RMLA11 carried altered sequences in the first repeat, in both the first and second repeats, and in the third repeat, respectively. The introduced sequence alterations were the same as those used for the construction of pBIAW2, pBIBM19, pBIBM8, and pBIBM34, respectively. Plasmid pEXSA564 was introduced into these strains, and the β-galactosidase activities were estimated in the presence and absence of IPTG. It was found that alfA-lacZ expression was repressed by the addition of IPTG in strains WILA2, LMLA2, and RMLA11, but not in MDLA13 (Table 2). The variations in the β-galactosidase activities seen without the addition of IPTG may have been due to the sequence alterations in the repeat sequences, which might have affected the alf operon transcription. Apparently, the higher activity in strain RMLA11 was due to the sequence alteration, which resulted in a −35 sequence closer to the consensus sequence of the σA-type promoter (from 5′-TTTACG-3′ to 5′-TTGACG-3′). The result with strain MDLA13 also shows that the transcription level of the alf operon was similar to that in strain WILA2 (Table 2), indicating that the instability of pBIBM8 carrying sequence alterations in the first and second repeats was not caused by a defect in transcription of the alf operon. These results show that the repression of alfA expression is correlated with the binding of AlfB, in that where alfA-lacZ was repressed, AlfB bound to the parN region (Fig. 7).

TABLE 2.

Effects of overproduction of AlfB on expression of alf-lacZ carrying sequence alterations in the upstream repeat sequencesa

| Strain | Sequence alterationb | IPTGc | β-Galactosidase activityd |

|---|---|---|---|

| WILA2 | Wild type | − | 381 |

| WILA2 | Wild type | + | 51 |

| LMLA2 | Rp1 | − | 457 |

| LMLA2 | Rp1 | + | 54 |

| MDLA13 | Rp1 and Rp2 | − | 416 |

| MDLA13 | Rp1 and Rp2 | + | 393 |

| RMLA11 | Rp3 | − | 717 |

| RMLA11 | Rp3 | + | 154 |

The experimental conditions are described in Materials and Methods, except that the media contained Cm. The data set is from one of two experiments, in which the variations of the enzyme levels were within 15%.

Rp1, -2, and -3 refer to the sequence alterations in the first, second, and third repeat sequences, respectively.

+, present; −, absent.

The levels of β-galactosidase activity in Miller units were determined for the samples taken from T1 to T4, and the highest values attained at either T0 or T1 are shown.

Interaction of AlfA and AlfB as shown by the yeast two-hybrid system.

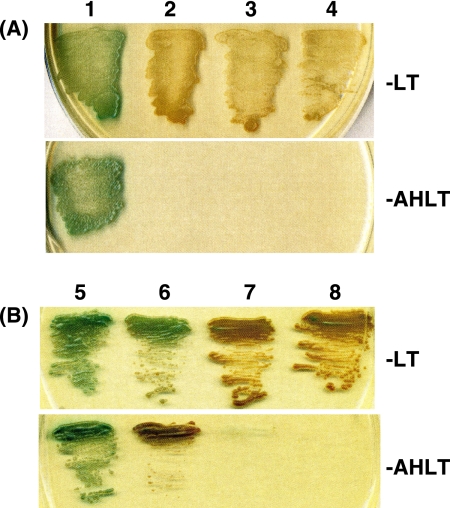

AlfA belongs to a new family of actins and forms actin-like filaments inside the cell (3). It is known that the E. coli plasmid R1 partitions with the help of a partition complex consisting of the actin-like protein ParM and the ParR protein bound to the centromere-like parC region (15, 29). To study if the partition system of pBET131 also involves interaction between AlfA and AlfB, the yeast Gal4 two-hybrid system was used. The yeast strain AH109 used as the host carries three reporters, ADE2, HIS3, and MEL1, which are under the control of distinct GAL4 upstream activating sequences and TATA boxes, and these features help to eliminate false positives (2, 21). The strain shows the phenotype Ade− His− Trp− Leu−, and the vector plasmids pGBKT7 and pGADT7 complement the Leu− and Trp− phenotypes, respectively. The interaction of a protein fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain in pGBKT7 with a protein fused to the GAL4 activation domain in pGADT7 renders the host cell growth independent of histidine and adenine. In addition, the protein-protein interaction causes the secretion of α-galactosidase encoded by MEL1, whose activity can be measured on a plate containing X-α-Gal (1). The alfA and alfB genes were cloned in pGBKT7 and pGADT7 by transformation of E. coli JM103, resulting in pGBA3 (alfA) and pGAB142 (alfB), respectively. The constructed plasmids and the vectors were transformed into AH109 in various combinations, and the colonies formed on the −Leu, −Trp (−LT) selection plates were patched on both the −LT and −AHLT (lacking Leu, Trp, Ade, and His) plates containing X-α-Gal. It was found that all the transformants carrying pGBKT7 (vector) or its derivative pGBA3 (alfA) together with pGADT7 (vector) or its derivative pGAD142 (alfB) showed growth on the −LT plate, but only the cells transformed with pGBA3 (alfA) and pGAB142 (alfB) turned blue (Fig. 8A, top). Furthermore, on the −AHLT plate, only the cells carrying these plasmids grew and turned blue (Fig. 8A, bottom).

FIG. 8.

Yeast two-hybrid system displaying the interaction between AlfA and AlfB (A) and among themselves (B). The AH109 transformants were grown overnight in minimal SD medium supplemented with a DO supplement lacking Leu and Trp, centrifuged, and resuspended in SD medium. The suspensions were patched on X-α-Gal-containing SD plates with DO supplements lacking either Leu and Trp (−LT) or Ade, His, Leu, and Trp (−AHLT). (A) Lanes: 1, AH109 carrying pGBA3 (alfA) and pGAB142 (alfB); 2, pGBA3 (alfA) and pGADT7 (vector); 3, pGBKT7 (vector) and pGAD142 (alfB); 4, pGBKT7 (vector) and pGADT7 (vector). (B) Lanes: 5, AH109 carrying pGBA3 (alfA) and pGA51 (alfA); 6, pGAB142 (alfB) and pGB64 (alfB); 7, pGA51 (alfA) and pGBKT7 (vector); 8, pGB64 (alfB) and pGADT7 (vector).

We next studied the interaction of the AlfA and AlfB proteins among themselves. To do this, the alfA and alfB genes were cloned in the vectors pGADT7 and pGBKT7, respectively, resulting in pGA51 (alfA) and pGB64 (alfB). The AH109 cells transformed with pGBA3 and pGA51, both of which carried the alfA gene, and those transformed with pGB64 and pGAB142, both of which carried the alfB gene, grew and turned blue on both the −LT and −AHLT plates containing X-α-Gal, whereas neither the transformants carrying pGA51 (alfA) and pGBKT7 (vector) nor those carrying pGB64 (alfB) and pGADT7 (vector) formed colonies on the −AHLT plate (Fig. 8B).

The following control experiments were performed to eliminate false positives (T. Tanaka, data not shown). The plasmids carried in the blue colonies on the −AHLT plates were isolated and transformed into E. coli JM103, from which individual plasmids were isolated and checked for integrity. These plasmids were then used for transformation of AH109 as described above, resulting in identical phenotypes. Furthermore, the combinations of pGBA3 (alfA) or pGAB142 (alfB) with the unrelated fusion plasmid pGADT7-T or pGBKT7-53 (Table 1), respectively, did not support the growth of AH109 on the −AHLT plate. These results show specific interactions of the AlfA and AlfB proteins.

DISCUSSION

It was shown previously that the partition mechanism of the mini-pLS32 plasmid pBET131 involves an actin-like ATPase, AlfA (3). The current article reports a functional study of ParB. It was shown that AlfB binds to the parN region upstream of the alf operon consisting of three tandem repeats and that this binding most likely requires two consecutive repeats (see above). It was also shown that only the stable plasmids contain the parN region to which AlfB binds (Fig. 1 and 5), suggesting strongly that the binding of AlfB to parN is a prerequisite for the segregational stability of pBET131. Furthermore, there was a correlation between AlfB binding to parN and the repression of alfA expression (Table 2). These results are consistent with the notion that specific binding of AlfB to parN results in both plasmid stabilization and repression of alfA expression. Since overproduction of AlfA (see above) or deletion of alfB (3) results in a growth defect, one role of AlfB is to keep alf operon expression below a certain level so that appropriate amounts of AlfA and AlfB are produced.

Becker et al. showed that, after replication, pBET131 enters the forespore before septum formation (3). They also showed that AlfA filaments extend to the cell pole and that a pBET131 derivative carrying the oriN and parN regions is translocated to the prespore that is formed at an extreme end of the mother cell. AlfA has partial amino acid sequence similarity to ParM encoded on E. coli plasmid R1 (3). A model has been presented for the plasmid maintenance of R1, according to which the ParR protein binds to the centromere-like sequence parC, forming a partitioning complex, and ATP-bound ParM molecules attach to the complex via ParR and push the plasmid copies toward the cell poles as they grow in filaments in the cell (6, 27, 28, 29, 30).

The experiments with a yeast two-hybrid system revealed that the AlfA and AlfB proteins interact not only with each other, but also among themselves (Fig. 8). The interaction between the AlfA molecules was expected from the previous observation that they form filaments in the cell (3). On the other hand, the interaction between AlfA and AlfB and the formation of a complex between AlfB and parN suggest the possibility of formation of a ternary complex among them. An attempt to detect binding between a parN-containing DNA fragment and partially purified His-tagged ParA was unsuccessful (Tanaka, unpublished), suggesting that parN may not interact directly with AlfA. Thus, it is possible that another role of ParB is to interact with ParA for partition.

Taking the data together, and by analogy with the partition mechanism of plasmid R1, it is likely that AlfB and parN form a DNA-protein complex to which AlfA binds successively to form actin-like filaments, presumably pushing the AlfB-parN complex toward the cell pole. Although the overall partition mechanism of pBET131 may be similar to that of R1, they are different in details: parR carries 10 10-bp repeats (38) as opposed to three 8-bp repeats in parN, the AlfA filaments are more stable than the ParM filaments, and AlfA forms highly twisted, helical filaments (35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank K. Asakawa, Y. Hirabayashi, and M. Uto for technical assistance; M. Ogura for discussion; and P. de Haseth for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B and C) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aho, S., A. Arffman, T. Pummi, and J. Uitto. 1997. A novel reporter gene MEL1 for the yeast two-hybrid system. Anal. Biochem. 253:270-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel, P. L., C.-T. Chien, R. Sternglanz, and S. Fields. 1993. Elimination of false positives that arise in using the two-hybrid systems. Biotechniques 14:920-924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker, E., N. C. Herrera, F. Q. Gunderson, A. I. Derman, A. Dancce, J. Sims, R. A. Larsen, and J. Pogliano. 2006. DNA segregation by the bacterial actin AlfA during Bacillus subtilis growth and development. EMBO J. 25:5919-5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouet, J. Y., and B. E. Funnell. 1999. P1 ParA interacts with the P1 partition complex at parS and an ATP-ADP switch controls ParA activities. EMBO J. 18:1415-1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouet, J. Y., J. A. Surtees, and B. E. Funnell. 2000. Stoichiometry of P1 plasmid partition complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8213-8219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, C. S., and R. D. Mullins. 2007. In vivo visualization of type II plasmid segregation: bacterial actin filaments pushing plasmids. J. Cell Biol. 179:1059-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, M. A., and S. J. Austin. 1988. Recognition of the P1 plasmid centromere analog involves binding of the ParB protein and is modified by a specific host factor. EMBO J. 7:1881-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Hoz, A. B., S. Ayora, I. Sitkiewicz, S. Fernandez, R. Pankiewicz, J. C. Alonso, and P. Ceglowski. 2000. Plasmid copy-number control and better-than-random segregation genes of pSM19035 share a common regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:728-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dmowski, M., I. Sitkiewicz, and P. Ceglowski. 2006. Characterization of a novel partition system encoded by the delta and omega genes from the streptococcal plasmid pSM19035. J. Bacteriol. 188:4362-4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francia, M. V., K. E. Weaver, P. Goicoechea, P. Tille, and D. B. Clewell. 2007. Characterization of an active partition system for the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responding plasmid pAD1. J. Bacteriol. 189:8546-8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garner, E. C., C. S. Campbell, D. B. Weibel, and R. D. Mullins. 2007. Reconstitution of DNA segregation driven by assembly of a prokaryotic actin homolog. Science 315:1270-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnier, T., W. Saurin, and S. T. Cole. 1987. Molecular characterization of the resolvase gene, res, carried by a multicopy plasmid from Clostridium perfringens: common evolutionary origin for prokaryotic site-specific recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 1:371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerdes, K., J. Moller-Jensen, and J. R. Bugge. 2000. Plasmid and chromosome partitioning: surprises from phylogeny. Mol. Microbiol. 37:455-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatano, T., Y. Yamaichi, and H. Niki. 2007. Oscillating focus of SopA associated with filamentous structure guides partitioning of F plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1198-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helinski, D. R., A. E. Toukdarian, and R. R. Novick. 1996. Replication control and other stable maintenance mechanisms of plasmids, p. 2295-2324. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 16.Henner, D. J. 1990. Inducible expression of regulatory genes in Bacillus subtilis. Methods Enzymol. 185:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiraga, S. 1992. Chromosome and plasmid partitioning in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:283-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano, M., H. Mori, T. Onogi, M. Yamazoe, H. Niki, T. Ogura, and S. Hiraga. 1998. Autoregulation of the partition genes of the mini-F plasmid and the intracellular localization of their products in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:392-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itaya, M., and T. Tanaka. 1997. Experimental surgery to create subgenomes of Bacillus subtilis 168. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:5378-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itaya, M., and T. Tanaka. 1999. Fate of unstable Bacillus subtilis subgenome: re-integration and amplification in the main genome. FEBS Lett. 448:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James, P., J. Halladay, and E. A. Craig. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen, R. B., and K. Gerdes. 1997. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The ParM protein exhibits ATPase activity and interacts with the centromere-like ParR-parC complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269:505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kearney, K., G. F. Fitzgerald, and J. F. Seegers. 2000. Identification and characterization of an active plasmid partition mechanism for the novel Lactococcus lactis plasmid pCI2000. J. Bacteriol. 182:30-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulakauskas, S., A. Lubys, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1995. DNA restriction-modification systems mediate plasmid maintenance. J. Bacteriol. 177:3451-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laesen, R. A., C. Cusumano, A. Fujioka, G. Lim-Fong, P. Patterson, and J. Poliano. 2007. Treadmilling of a prokaryotic tubulin-like protein, TubZ, required for plasmid stability in Bacillus thuringiensis. Genes Dev. 21:1340-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lereclus, D., and O. Arantes. 1992. SpbA locus ensures the segregational stability of pTH1030, a novel type of gram-positive replicon. Mol. Microbiol. 6:35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moller-Jensen, J., J. Borch, M. Dam, R. B. Jensen, P. Roepstorff, and K. Gerdes. 2003. Bacterial mitosis: ParM of plasmid R1 moves plasmid DNA by an actin-like insertional polymerization mechanism. Mol. Cell 12:1477-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moller-Jensen, J., and K. Gerdes. 2007. Plasmid segregation: spatial awareness at the molecular level. J. Cell Biol. 179:813-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moller-Jensen, J., R. B. Jensen, J. Lowe, and K. Gerdes. 2002. Prokaryotic DNA segregation by an actin-like filament. EMBO J. 21:3119-3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moller-Jensen, J., S. Ringgaard, C. P. Mercogliano, K. Gerdes, and J. Lowe. 2007. Structural analysis of the ParR/parC plasmid partition complex. EMBO J. 26:4413-4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori, H., Y. Mori, C. Ichinose, H. Niki, T. Ogura, A. Kato, and S. Hiraga. 1989. Purification and characterization of SopA and SopB proteins essential for F plasmid partitioning. J. Biol. Chem. 264:15535-15541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordstrom, K., and S. J. Austin. 1989. Mechanisms that contribute to the stable segregation of plasmids. Annu. Rev. Genet. 23:37-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogura, M., A. Matsuzawa, H. Yoshikawa, and T. Tanaka. 2004. Bacillus subtilis SalA (YbaL) negatively regulates expression of scoC encoding the repressor for the alkaline exoprotease gene, aprE. J. Bacteriol. 186:3056-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pérez-Martín, J., G. H. del Solar, A. G. de la Campa, and M. Espinosa. 1988. Three regions in the DNA of plasmid pLS1 show sequence-directed static bending. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:9113-9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polka, J. K., J. M. Kollman, D. A. Agard, and R. D. Mullins. 2009. The structure and assembly dynamics of plasmid actin AlfA imply a novel mechanism of DNA segregation. J. Bacteriol. 191:6219-6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pratto, F., A. Cicek, W. A. Weihofen, R. Lurz, W. Saenger, and J. C. Alonso. 2008. Streptococcus pyogenes pSM19035 requires dynamic assembly of ATP-bound ParA and ParB on parS DNA during plasmid segregation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:3676-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rojo, F., and J. C. Alonso. 1994. A novel site-specific recombinase encoded by the Streptococcus pyogenes plasmid pSM19035. J. Mol. Biol. 238:159-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saije, J., and J. Lowe. 2008. Bacterial actin: architecture of the ParMRC plasmid DNA partitioning complex. EMBO J. 27:2230-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaeffer, P. J., J. Millet, and J. Aubert. 1965. Catabolite repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 54:704-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schumacher, M. A., T. C. Glover, A. J. Brzoska, S. O. Jensen, T. D. Dunham, R. A. Skurray, and N. Firth. 2007. Segrosome structure revealed by a complex of ParR with centromere DNA. Nature 450:1268-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson, A. E., R. A. Skurray, and N. Firth. 2003. A single gene on the staphylococcal multiresistance plasmid pSK1 encodes a novel partitioning system. J. Bacteriol. 185:2143-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stragier, P., C. Bonamy, and C. Karmazyn-Campelli. 1988. Processing of a sporulation sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis: how morphological structure could control gene expression. Cell 527:697-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swinfield, T. J., L. Janniere, S. D. Ehrlich, and N. P. Minton. 1991. Characterization of a region of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAMβ1 which enhances the segregational stability of pAMβ1-derived cloning vectors in Bacillus subtilis. Plasmid 26:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka, T., H. Ishida, and T. Maehara. 2005. Characterization of the replication region of plasmid pLS32 from the Natto strain of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187:4315-4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka, T., and T. Koshikawa. 1977. Isolation and characterization of four types of plasmids from Bacillus subtilis (natto). J. Bacteriol. 131:699-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka, T., and M. Ogura. 1998. A novel Bacillus natto plasmid pLS32 capable of replication in Bacillus subtilis. FEBS Lett. 422:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsukahara, K., and M. Ogura. 2008. Promoter selectivity of the Bacillus subtilis response regulator DegU, a positive regulator of the fla/che operon and sacB. BMC Microbiol. 8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward, J. B., Jr., and S. A. Zahler. 1973. Genetic studies of leucine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 116:719-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weaver, K. E., K. D. Jensen, A. Colwell, and S. I. Sriram. 1996. Functional analysis of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded stability determinant par. Mol. Microbiol. 20:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams, D. R., and C. M. Thomas. 1992. Active partitioning of bacterial plasmids. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida, K.-I., K. Kobayashi, Y. Miwa, C.-M. Kang, M. Matsunaga, H. Yamaguchi, S. Tojo, M. Yamamoto, R. Nishi, N. Ogasawara, T. Nakayama, and Y. Fujita. 2001. Combined transcriptome and proteome analysis as a powerful approach to study genes under glucose repression in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:683-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zielenkiewicz, U., and P. Ceglowski. 2005. The toxin-antitoxin system of the streptococcal plasmid pSM19035. J. Bacteriol. 187:6094-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.