Abstract

Bacterial toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems typically consist of a small, labile antitoxin that inactivates a specific longer-lived toxin. In Escherichia coli, such antitoxins are proteolytically regulated by the ATP-dependent proteases Lon and ClpP. Under normal conditions, antitoxin synthesis is sufficient to replace this loss from proteolysis, and the bacterium remains protected from the toxin. However, if TA production is interrupted, antitoxin levels decrease, and the cognate toxin is free to inhibit the specific cellular component, such as mRNA, DnaB, or gyrase. To date, antitoxin degradation has been studied only in E. coli, so it remains unclear whether similar mechanisms of regulation exist in other organisms. To address this, we followed antitoxin levels over time for the three known TA systems of the major human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus, mazEF, axe1-txe1, and axe2-txe2. We observed that the antitoxins of these systems, MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2, respectively, were all degraded rapidly (half-life [t1/2], ∼18 min) at rates notably higher than those of their E. coli counterparts, such as MazE (t1/2, ∼30 to 60 min). Furthermore, when S. aureus strains deficient for various proteolytic systems were examined for changes in the half-lives of these antitoxins, only strains with clpC or clpP deletions showed increased stability of the molecules. From these studies, we concluded that ClpPC serves as the functional unit for the degradation of all known antitoxins in S. aureus.

Staphylococcus aureus is a versatile human pathogen responsible for an increasing number of hospital- and community-acquired infections (33, 41) ranging from superficial skin lesions to life-threatening sepsis, endocarditis, and toxic shock (29). S. aureus' capacity to cause illness is enhanced by its robust stress response, which allows it to endure adverse conditions, such as heat, antibiotics, and nutritional deprivation. This is mediated in part by transcriptional regulators, like CtsR (11), CodY (31), and the alternative sigma factor σB (24), that allow the bacteria to rapidly adjust to challenging environments.

The roles of chromosomal toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules in environmental and antibiotic stress response have been documented for a variety of organisms, especially Escherichia coli, but only recently have they been investigated in S. aureus (12, 18, 43). These systems typically consist of a pair of cotranscribed stress-inducible genes (19) that encode a stable toxin and a more labile antitoxin. Depletion of the antitoxin allows activation of its cognate toxin, which is then free to interfere with a specific cellular target, such as mRNA, DNA gyrase, or DNA helicase. Depending on the species and the TA system, this activation results in a variety of phenotypes, but those related to growth, stress response, starvation, and persistence are often seen (12, 19, 30). For example, Streptococcus mutans devoid of its TA systems is more susceptible to changes in nutrient availability and pH than its counterpart wild-type strains (26). Furthermore, TA systems are absent in obligate intracellular organisms (37), suggesting that they are not necessary for growth in stable intracellular environments.

Previous reports have demonstrated that at least three TA systems exist in S. aureus (12, 43), annotated as mazEF (SAS0167/SA1873), axe1-txe1 (SA2196-5), and axe2-txe2 (SA2246-5). Although mazEF was named for its similarity to mazEF in E. coli, its transcriptional regulation (12) and ribonucleic target sequences are considerably different from those of E. coli mazEF (17). The axe1-txe1 and axe2-txe2 TA systems have significant homology to one another (48% amino acid similarity for both antitoxins and toxins), as well as to both the relBE (37) and yefM-yoeB (6) TA systems in E. coli. Like the mazEF system, both of the systems in S. aureus show transcriptional activation in response to select antibiotics (12) and have specific endoribonucleic activities (43).

As a functional family, antitoxins can be either small RNAs (class I) or proteins (class II) (20) that specifically bind to a cognate toxin and inhibit its enzymatic activity; in the case of S. aureus, all three antitoxins appear to belong to the latter group (12, 43). Class II antitoxins are often strongly acidic and are thought to be largely unstructured (28), attributes that facilitate the conformational changes necessary to enable the tight binding needed to repress their positively charged toxins. The unfolded nature of these antitoxins is also thought to contribute to their degradation (34), as protein unfolding is an important first step in the delivery and processing of the target protein by ATP-dependent proteases.

While the TA systems of a variety of bacteria have been shown to respond transcriptionally to environmental and antibiotic stresses (4, 12), little is known about the proteolytic regulation of TA systems in species other than E. coli (19). In that organism, two of the four proteolytic systems (Lon, ClpP, FtsH, and HslVU [ClpQY]) are involved in antitoxin degradation: Lon breaks down the antitoxins RelB (9), MazE (10), ParD (39), and CcdA (42), while the ClpP protease degrades MazE (1), PhD (25), and YefM (6). On its own, ClpP can degrade only small peptides, but it employs an Hsp100/Clp ATPase chaperone (1, 25) to unfold and translocate proteins with specific amino acid signal sequences (e.g., C-terminal AA and LCN motifs) (8, 36, 38) into its proteolytic core. In E. coli, the ClpA and ClpX chaperones have both been shown to be critical to this ClpP-mediated antitoxin degradation, but their counterparts in S. aureus are less clear. S. aureus has a single homologue of E. coli ClpX, but it also possesses several chaperones that have high similarity to ClpA (ClpB [59%], ClpC [61%], and ClpL [61%]). Among these, only ClpC and ClpX are thought to contain ClpP recognition sequences (14), suggesting that ClpB and ClpL might not directly bind ClpP (although that may not be a requirement to function as a ClpP chaperone). In terms of function in S. aureus, ClpC appears to mediate resistance to oxidative stress, enhance growth recovery from the stationary and poststationary phases, and contribute to biofilm formation (5). ClpX has a role in osmoprotection and, interestingly, also controls aspects of virulence gene regulation through an unidentified regulator of the agr system (15). Less is known of the two other chaperones, ClpB and ClpL, although roles in thermotolerance have been suggested (14).

While neither of the other two ATP-dependent proteases in E. coli, FtsH and HslVU, has been shown to be involved in antitoxin degradation, S. aureus homologues of these proteases conceivably could compensate for the lack of Lon. Strains lacking FtsH have defects in osmotic and heat shock tolerance, general cell growth, and starvation (27), phenotypes associated with TA systems. Little is known of HslVU's cellular function in S. aureus other than that it has a limited role in stress survival (16).

We report here that the antitoxins MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 from the three known TA systems in S. aureus are each rapidly degraded in vivo, with half-lives (t1/2) of approximately 18 min, rates that are faster than those of their E. coli counterparts. Examination of the genetic components involved in S. aureus antitoxin degradation revealed that strains lacking clpP showed greatly decreased degradation rates for all three antitoxins, while the rates were unchanged in ftsH- and hslV-deficient strains. The chaperone ClpC was also shown to be the only ATPase chaperone necessary for antitoxin breakdown. This indicated that while S. aureus uses ClpP to degrade its antitoxins in a manner similar to that of E. coli, S. aureus TA regulation is distinct from that of E. coli in that it employs the Gram-positive-specific stress response chaperone ClpC (5, 14) to facilitate antitoxin breakdown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

Table 1 contains a list of bacterial strains and plasmids used for this study. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on plates containing LB agar, and S. aureus was grown in trypticase soy broth (TSB) or agar (TSA). Competent S. aureus bacteria were prepared in B2 medium as described previously (40). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: erythromycin, 2.5 μg/ml; ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml; and rifampin, 200 μg/ml. Xylose induction was performed using 0.1% (vol/vol) xylose.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue | General cloning strain | Agilent Technologies |

| S. aureus | ||

| 8325-4 | General laboratory strain; rsbU mutant | 35 |

| RN4220 | Heavily mutagenized NCTC8325-4 | 23 |

| SH1000 | 8325-4 with a repaired rsbU gene | 21 |

| SaΔclpP | 8325-4 with a clpP deletion | 15 |

| JM27 | SH1000 ftsH::tet Tetr | 27 |

| ALC4976 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpB | This work |

| ALC4977 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpC | This work |

| ALC4978 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpL | This work |

| ALC4979 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpQ | This work |

| ALC4980 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpX | This work |

| ALC4981 | SH1000 clean selectionless deletion of clpY | This work |

| ALC5105 | SaΔclpP with a repaired rsbU gene | This work |

| ALC6490 | SH1000 clpC complement | This work |

| ALC6491 | SH1000 clpP complement | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMAD | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle plasmid with the ori pE194ts; bgaB Ampr Ermr | 3 |

| pCR2.1 | E. coli PCR cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pEPSA5 | Xylose-inducible shuttle vector; Ampr Cmr | 13 |

| pALC4384 | pMAD::ΔclpY | This work |

| pALC4404 | pMAD::ΔclpB | This work |

| pALC4440 | pMAD::ΔclpQ | This work |

| pALC4506 | pMAD::ΔclpC | This work |

| pALC4507 | pMAD::ΔclpL | This work |

| pALC4508 | pMAD::ΔclpX | This work |

| pALC4946 | pMAD::rsbU complement | This work |

| pALC4077 | pEPSA5::mazE | This work |

| pALC6188 | pEPSA5::mazEC-myc with a C-terminal Myc tag | This work |

| pALC6486 | pEPSA5::axe1N-myc with a N-terminal Myc tag | This work |

| pALC6489 | pEPSA5::axe2C-myc with a C-terminal Myc tag | This work |

| pALC6682 | pEPSA5::axe2C-HA with a C-terminal HA tag | This work |

| pALC6492 | pMAD::clpC complement | This work |

| pALC6493 | pMAD::clpP complement | This work |

DNA manipulations.

E. coli plasmid purification was performed using Qiagen miniprep kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, while plasmid isolation from S. aureus was performed as described previously (40). Transformations of S. aureus by plasmids were done via electroporation, using the heavily mutagenized RN4220 as an intermediate between E. coli and relevant S. aureus strains (40). The sequences of the primers used (IDT Technologies) are available upon request.

Expression vector creation.

To facilitate their detection in cell lysates, the MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 antitoxins were epitope tagged with either N- or C-terminal Myc (EQKLISEEDL) or hemagglutinin (HA) (YPYDVPDYA) tags codon optimized for S. aureus. These tag sequences were joined to the antitoxin genes by PCR amplification from the SH1000 chromosome, along with an upstream EcoRI site, a sarA ribosome-binding site, and a downstream XbaI site. The products were digested using EcoRI and XbaI, ligated into a similarly digested pEPSA5 vector, and used to transform competent E. coli XL1-Blue. Successful transformants were verified by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing.

Construction of clp knockouts.

The S. aureus genome contains genes for five Clp ATPases (clpB, clpC, clpL, clpX, and clpY) and three ATP-dependent peptidases (hslV [clpQ], clpP, and ftsH) (14, 27). Deletion of the first six of these genes was performed in the SH1000 background using the temperature-sensitive allelic replacement plasmid pMAD (3) to create clean, markerless deletions of individual clp genes. Verification of theses deletions was performed by colony PCR and chromosomal sequencing. For the clpP mutant in the SH1000 background, we repaired the 11-bp deletion in rsbU in the ΔclpP mutant of 8325-4 using a similar pMAD replacement strategy. Since the small size of this replacement made the identification of a successful rsbU repair impractical by colony PCR, enhanced pigmentation in putative rsbU+ strains was used for our initial selection (24), followed by chromosomal sequencing of pigment-positive strains for an intact rsbU gene. The SH1000 ftsH::tetM strain was a kind gift from S. Foster (27).

Protein lysate preparation.

To prepare protein lysates of SH1000 strains, overnight cultures of S. aureus were diluted 1/100 in 100 ml of TSB and grown with shaking at 250 rpm at 37°C (flask/medium ratio, 2.5:1). For those strains overexpressing antitoxins from the pEPSA5 plasmid, 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 0.1% xylose were also added during the initial inoculation. At an A650 of 1.1, 200 μg/ml rifampin was added to inhibit transcription (2), whereupon a 10-ml aliquot was immediately withdrawn. Similar samples were taken every 15 min thereafter. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1°C, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Once cells at all time points were collected, the cells were thawed on wet ice and washed twice with ice-cold sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 50 mM EDTA). The cells were then resuspended in 300 μl of sample buffer, and 100 μl of 0.1-mm silica/glass beads was added and then mechanically disrupted in a Mini-beadbeater 8 at its maximum setting for two 1-min pulses punctuated by a 1-min rest on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 1°C, and then aprotinin (1 μg/ml), leupeptin (1 μg/ml), and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (300 μM) were added to the clarified supernatants, and their protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay on a FL600 microplate reader (Biotek Instruments).

Western blot analysis.

Twenty-five micrograms of lysate from the S. aureus strains described above were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and blocked overnight in Tris-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0) with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TBS-T) and 5% dried milk. The membranes were then incubated with either mouse anti-HA (α-HA) (Cell Signaling), α-Myc (Cell Signaling), α-SarA (32), α-σB (7), α-MazFsa (17), or α-MazEsa (17) antibodies in TBS-T for 2 h; washed three times with TBS-T for 5 min each time; treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat α-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min; and washed again with TBS-T three times for 5 min each time. The membranes were then covered with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (GE Healthcare) and exposed to film. Scanned images from nonsaturated exposed film were then analyzed densitometrically using ImageJ, and the half-lives were calculated using Prism 5 (Graphpad).

RESULTS

Evaluation of protein stability in S. aureus following transcriptional inhibition.

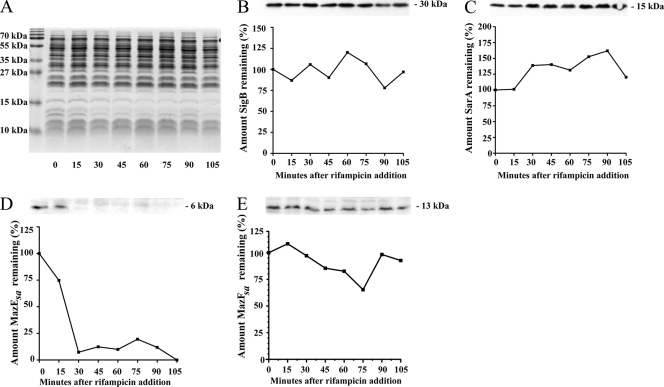

MazE degradation in E. coli was first shown by comparing time points of lysates of 35S-labeled cells grown during heat shock at 42°C, a condition that represses MazE production (1). A more specific approach was used in our studies, in which antitoxin levels were determined by Western blotting, a method similar to that used by Christensen et al. for RelB (9). To more easily expose the changes in antitoxin levels over time, rifampin was added to cultures at a level sufficient to stall RNA polymerase (200 μg/ml) and block any further transcription of TA mRNA (2). The use of a transcriptional inhibitor like rifampin was desirable, because antibiotics such as macrolides and tetracyclines that block translation also have the undesirable effect of upregulating TA transcription in S. aureus (12). However, to provide evidence that this treatment did not alter protein levels in S. aureus in general, equivalent amounts of lysates from strain SH1000 were separated using SDS-PAGE and either Coomassie stained or Western blotted using α-SarA or α-σB antibodies. As seen in Fig. 1A, rifampin treatment produced no gross changes in protein over the course of treatment, and both σB (Fig. 1B) and SarA (Fig. 1C) levels remained steady. This indicated that using rifampin to transcriptionally stall S. aureus did not lead to significant changes in the general turnover of cellular proteins.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of protein levels of lysates at different time points from S. aureus strains grown to an A650 of 1.1 and then treated with rifampin (200 μg/ml). (A) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained wild-type SH1000 lysates separated by SDS-PAGE. (B and C) Lysates of wild-type SH1000 lysates separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using primary antibodies specific for σB (B) and SarA (C). (D and E) Immunoblots of lysates from SH1000 with pALC4077 grown to an A650 of 1.1 with 0.1% xylose and then treated with rifampin (200 μg/ml). The immunoblots of these lysates used primary antibodies specific to MazEsa (D) and MazFsa (E). At the top of each panel is shown the bands from each Western blot, and the corresponding graph represents the calculation of the original amount of protein detected by densitometry before the addition of rifampin (t = 0). The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown.

MazEsa is rapidly degraded in S. aureus, while MazFsa is stable.

As antitoxin degradation is one of the key aspects of E. coli TA regulation, we examined whether the S. aureus MazEsa antitoxin was regulated in a similar manner. Western blots of lysates made from transcriptionally stalled SH1000 cells overexpressing MazEsa were probed with α-MazEsa antibodies and showed that the MazEsa levels rapidly decreased over time after rifampin treatment to the point where the protein was nearly undetectable after 30 min (Fig. 1D). Densitometry of this progression indicated MazEsa has an in vivo half-life of between 18 and 20 min, a rate faster than that reported for MazE of E. coli (t1/2 = 30 min) (1). To determine if the S. aureus MazFsa toxin was more stable than its cognate antitoxin, MazFsa levels were tracked by immunoblotting rifampin-treated SH1000 cell lysates using α-MazFsa antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1E, in contrast to the antitoxin MazEsa, MazFsa levels remained relatively constant after transcriptional inhibition. This indicated that the S. aureus mazEF TA system was posttranslationally regulated in a manner similar to that of its homologue in E. coli.

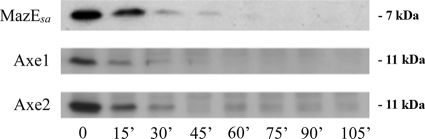

Axe1 and Axe2 are degraded rapidly in vivo.

We next examined whether the other two known antitoxins of S. aureus exhibited degradation patterns similar to that of MazEsa. To circumvent the issue that antisera to Axe1 and Axe2 were unavailable, epitope-tagged versions of these antitoxins were created to facilitate their detection. An in silico analysis suggested that the addition of an HA or Myc tag to either terminus caused no secondary-structure changes but also did not reveal any known motifs involved in Clp-specific degradation (e.g., LCN, FMLYPK, or AA motifs from Bacillus subtilis) (8, 36, 38). To guard against the possibility that such a tag could affect the degradation of these proteins, separate constructs were made that fused either HA or Myc epitope tags to the N or C terminus of each antitoxin. As a related control, we compared the degradation rate of untagged MazEsa to that of Myc-tagged MazEsa and determined the half-life to be essentially unchanged (20 minutes versus 18 min) (Fig. 1D and 2). With this information, we proceeded to transcriptionally stall SH1000 wild-type cells containing pEPSA5 plasmids capable of overexpressing either axe1 or axe2 and withdrew samples every 15 min. Western blot analysis of lysates made from these cells revealed that the levels of both HA- and Myc-tagged antitoxins of Axe2 dropped rapidly after rifampin treatment (t1/2 = 20 min for Myc- and HA-tagged antitoxins) (Fig. 2 [also see Fig. 6A] for the Myc tag; see Fig. 7A for the HA tag). Similarly, Axe1 tagged with Myc (Fig. 2 [also see Fig. 5A]) or HA (data not shown) displayed similar but rapid degradation rates in strain SH1000. From these data, we concluded that the Axe1 and Axe2 antitoxins were rapidly degraded in a fashion similar to that of MazEsa in S. aureus.

FIG. 2.

Axe1 and Axe2 levels in S. aureus SH1000 wild-type cells following transcriptional arrest with rifampin. Wild-type SH1000 was transformed with pEPSA5::mazEC-myc (pALC6188), pEPSA5::axe1N-myc (pALC6486), or pEPSA5::axe2C-myc (pALC6489); grown to an A650 of 1.1 with 0.1% xylose; and then treated with rifampin (200 μg/ml). Samples were taken every 15 min, lysed, and then separated by SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting with an α-Myc primary antibody. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are displayed.

FIG. 6.

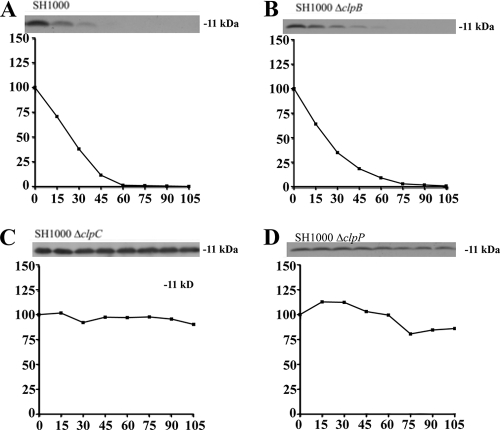

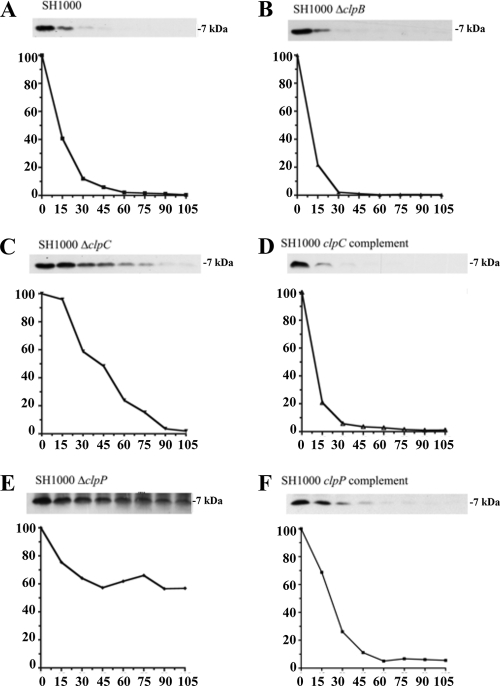

Comparative rates of Axe2 degradation in SH1000 wild-type and clp mutant strains. Wild-type (A), ΔclpB (B), ΔclpC (C), clpC complemented (D), ΔclpP (E), and clpP complemented (F) strains were transformed with pEPSA5::axe2C-myc (pALC6489). The cells were treated and analyzed like those in Fig. 4. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown.

FIG. 7.

Comparative rates of Axe2 degradation in SH1000 wild-type and clp mutant strains with an alternate HA epitope tag. Wild-type (A), ΔclpB (B), ΔclpC (C), and ΔclpP (D) strains were transformed with pEPSA5::axe2C-HA (pALC6682). At the top of each panel is a Western blot from the respective time points using a primary α-HA antibody. The graphs depict the percentage of signal at each time point compared to t = 0. The cells were analyzed like those in Fig. 4. The experiments were repeated twice, and representative blots are shown.

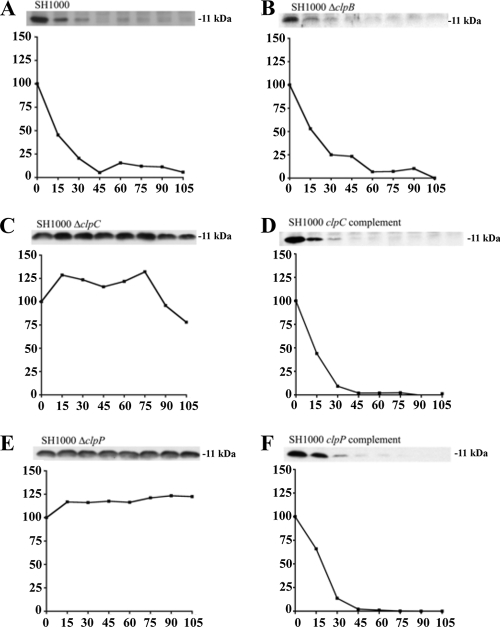

FIG. 5.

Comparative rates of Axe1 degradation in SH1000 wild-type and clp mutant strains. Wild-type (A), ΔclpB (B), ΔclpC (C), clpC complemented (D), ΔclpP (E), and clpP complemented (F) strains were transformed with pEPSA5::axe1N-myc (pALC6486). The cells were treated and analyzed like those in Fig. 4. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown.

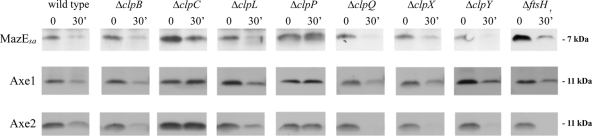

clpP and clpC are required for antitoxin degradation in S. aureus.

To date, all proteolysis of E. coli antitoxins appears to be through Lon or ClpP (19), with the latter deploying ClpA or ClpX ATPase chaperones for this destruction. However, the mechanism(s) of this degradation in S. aureus is less clear, as not only does it lack a Lon homologue, it also contains several Hsp100/Clp ATPases with similar levels of homology to ClpA (ClpB [59% similarity], ClpC [61%], and ClpL [61%]). To clarify the degradative mechanism, SH1000 strains lacking either the three known ATP-dependent protease genes, ftsH, clpP, and hslV (clpQ), or their chaperones, clpB, clpC, clpL, clpX, and clpY (hslU), were made. These strains were then transformed with either pALC6188, pALC6486, or pALC6489 for ectopic overexpression of Myc-tagged MazEsa, Axe1, or Axe2, respectively. Lysates were then made from these strains either at time points immediately following rifampin treatment or after 30 min and then analyzed by Western blotting with α-Myc antibodies. As seen in Fig. 3, only lysates from strains lacking clpC or clpP showed defects in MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 degradation after 30 min, suggesting that clpP and clpC were involved in breakdown of all three S. aureus antitoxins.

FIG. 3.

Stability of S. aureus antitoxins in SH1000 wild type and strains lacking genes in various ATP-dependent proteolytic pathways. The wild-type and mutant strains were transformed with pEPSA5::mazEC-myc (pALC6188), pEPSA5::axe1N-myc (pALC6486), or pEPSA5::axe2C-myc (pALC6489) grown under inducing conditions (0.1% xylose), treated with 200 μg/ml rifampin, and harvested either immediately or after 30 min. Lysates of the samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with an α-Myc primary antibody. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown.

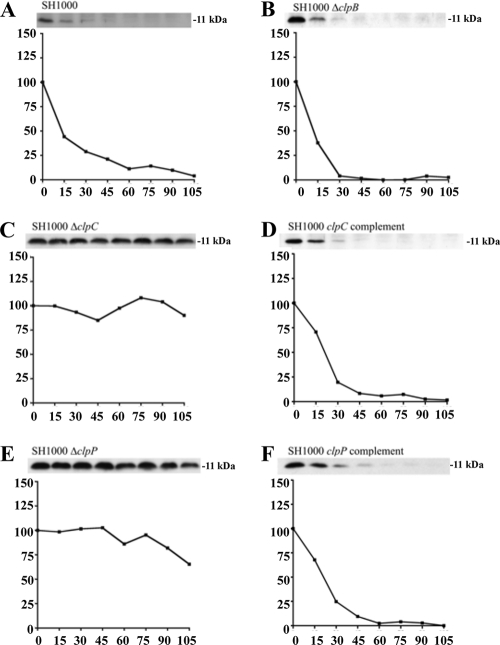

clpP, but not clpC, is essential for degradation of all S. aureus antitoxins.

We next examined the overall impact of clpC and clpP deletions on antitoxin breakdown. To do so, levels of Myc-tagged MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 were followed for almost 2 h in transcriptionally stalled wild-type SH1000 or in isogenic strains lacking either clpC, clpP, or clpB (as a control). As seen in Fig. 4E, 5E, and 6E, the levels of all three antitoxins remained unchanged in an SH1000 ΔclpP strain during these 2 h, while the ΔclpB-complemented (Fig. 4B, 5B, and 6B) and clpP-complemented (Fig. 4F, 5F, and 6F) strains showed degradation rates similar to those found in wild-type SH1000 (Fig. 4A, 5A, and 6A). A slightly different degradation pattern emerged when the SH1000 ΔclpC strain was examined. The MazEsa protein exhibited limited breakdown in the ΔclpC mutant (Fig. 4C) at a rate substantially lower (t1/2 = 46 min) than in the wild type (t1/2 = 12 min). In contrast, the levels of Axe1 and Axe2 remained steady throughout in the ΔclpC mutant (Fig. 5C and 6C). In support of our findings, the half-lives of the respective proteins were restorable to wild-type levels in a clpC-complemented strain (Fig. 4D, 5D, and 6D). To ensure that the Myc tag did not alter the profile of proteolysis of the antitoxin, we replaced the C-terminal Myc tag of Axe2 with an HA tag. Similar patterns of clpC- and clpP-dependent degradation were seen for these antitoxins with the HA tag and the Myc tag (Fig. 7). Similar data were obtained with Axe1 (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicated that clpP was essential for proteolysis of all three antitoxins in S. aureus, while clpC was involved in degradation of MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 but was essential for only the last two antitoxins.

FIG. 4.

Comparative rates of MazEsa degradation in SH1000 wild-type and clp mutant strains. Wild-type (A), ΔclpB (B), ΔclpC (C), clpC complemented (D), ΔclpP (E), and clpP complemented (F) strains were transformed with pEPSA5::mazEC-myc (pALC6188). The cells were induced and transcriptionally stalled similarly to those in Fig. 3. At the top of each panel is a Western blot from the respective time points using a primary α-Myc antibody. The graphs depict the percentage of signal at each time point compared to t = 0. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown.

DISCUSSION

Maintenance of antitoxin protein levels relies on continued synthesis in the host bacterium, while any disruption of the production process causes antitoxin levels to drop, leading to toxin activation. However, as antitoxin proteolysis has been described only for E. coli TA systems, our findings that the S. aureus ATP-dependent protease ClpP and its ATPase chaperone ClpC function to degrade the antitoxins MazEsa, Axe1, and Axe2 provide the first evidence that this mechanism of toxin activation by ClpP is conserved in Gram-positive bacteria, as well. Furthermore, the 12- to 20-min half-lives of the three S. aureus antitoxins were all considerably shorter than those of their closest E. coli homologues (MazE, 30 min [1]; YefM, 50 to 60 min [6]). These data suggest that the toxins of S. aureus TA systems might become activated much more quickly in response to stimuli than their E. coli counterparts, which is attributable to the faster decrease in S. aureus antitoxins levels.

Interestingly, the genetic components necessary for antitoxin breakdown were not absolute. While both ClpP and ClpC were essential for Axe1 and Axe2 degradation, the MazEsa level was found to decrease in the clpC mutant at one-quarter the rate of that of the wild type. This finding suggested several possibilities: (i) a second, unannotated chaperone might function to partially complement ClpC's breakdown of MazEsa; (ii) another ATP-dependent protease might also process MazEsa; and (iii) ClpP might still process MazEsa in the absence of ClpC. The third scenario may be the most likely, as (i) ClpC is essential for Axe1 and Axe2 degradation, (ii) no other clp-related gene deletion in our tested mutant strains resulted in a decreased MazEsa breakdown rate, (iii) deletion of hslV or ftsH did not alter antitoxin breakdown, and (iv) ClpP may be capable of slowly degrading proteins independently of an ATPase chaperone (22).

During our study of Axe1 and Axe2, two antitoxins with 48% amino acid similarity, we observed that the addition of either a Myc or an HA epitope tag to the N terminus of Axe2 could block its degradation, while a similar inhibitory pattern in Axe1 could be obtained only when these tags were added to its C terminus (data not shown). In silico analyses of these fusions suggested that the epitope tags did not alter the antitoxins' secondary structure, nor did they mask any motif known to be involved in Clp-specific degradation (e.g., LCN, FMLYPK, or AA motifs from B. subtilis) (8, 36, 38). We are currently investigating the basis of this proteolytic disparity.

As many TA systems do not have obvious phenotypes, identification of ClpPC as the functional protease in S. aureus antitoxin degradation may increase our understanding of the contributions of TA systems in this and other Gram-positive organisms. Previously, it was shown that the transcription of clpC and all three of S. aureus's TA systems was found to be increased upon heat shock (5, 12); the subsequent increase in ClpC levels may enhance toxin activity by virtue of increased capacity for antitoxin degradation. Furthermore, Chatterjee et al. (5) showed that a ΔclpC mutant strain survived better over 5 days of growth than the wild type, while a sigB mutant grew poorly in comparison. In light of our data, a portion of this increased survival of a ΔclpC strain may be due to the permanent inactivation of toxins that would result from the lack of antitoxin proteolysis. A similar phenotype may also be found in a strain lacking all its TA systems, as it would lack the restraints upon growth that TA systems seem to contribute. The ΔsigB growth phenotype may be due in part to the derepression of TA transcription that occurs in a ΔsigB strain (12). Such an increase would lead to the accumulation of stable toxins, which would necessitate an ever-increasing level of antitoxins. Such a demand would likely be unsustainable and result in toxin activation and, ultimately, decreased survival and/or slower growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simon Foster and Hanne Ingmer for their kind gifts of strains.

This work was supported in part by grants AI56114 and AI37142 from the NIH (to A.L.C.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizenman, E., H. Engelberg-Kulka, and G. Glaser. 1996. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:6059-6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, K. L., C. Roberts, T. Disz, V. Vonstein, K. Hwang, R. Overbeek, P. D. Olson, S. J. Projan, and P. M. Dunman. 2006. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J. Bacteriol. 188:6739-6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaud, M., A. Chastanet, and M. Debarbouille. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, Gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6887-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budde, P. P., B. M. Davis, J. Yuan, and M. K. Waldor. 2007. Characterization of a higBA toxin-antitoxin locus in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 189:491-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, I., P. Becker, M. Grundmeier, M. Bischoff, G. A. Somerville, G. Peters, B. Sinha, N. Harraghy, R. A. Proctor, and M. Herrmann. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus ClpC is required for stress resistance, aconitase activity, growth recovery, and death. J. Bacteriol. 187:4488-4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherny, I., and E. Gazit. 2004. The YefM antitoxin defines a family of natively unfolded proteins: implications as a novel antibacterial target. J. Biol. Chem. 279:8252-8261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung, A. L., Y. T. Chien, and A. S. Bayer. 1999. Hyperproduction of alpha-hemolysin in a sigB mutant is associated with elevated SarA expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 67:1331-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien, P., B. S. Perchuk, M. T. Laub, R. T. Sauer, and T. A. Baker. 2007. Direct and adaptor-mediated substrate recognition by an essential AAA+ protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6590-6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen, S. K., M. Mikkelsen, K. Pedersen, and K. Gerdes. 2001. RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:14328-14333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen, S. K., K. Pedersen, F. G. Hansen, and K. Gerdes. 2003. Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 332:809-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derre, I., G. Rapoport, and T. Msadek. 1999. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clp and molecular chaperone gene expression in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol.r Microbiol. 31:117-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donegan, N. P., and A. L. Cheung. 2009. Regulation of the mazEF toxin-antitoxin module in Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on sigB expression. J. Bacteriol. 191:2795-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsyth, R. A., R. J. Haselbeck, K. L. Ohlsen, R. T. Yamamoto, H. Xu, J. D. Trawick, D. Wall, L. Wang, V. Brown-Driver, J. M. Froelich, G. C. Kedar, P. King, M. McCarthy, C. Malone, B. Misiner, D. Robbins, Z. Tan, Z. Y. Zhu Zy, G. Carr, D. A. Mosca, C. Zamudio, J. G. Foulkes, and J. W. Zyskind. 2002. A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1387-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frees, D., A. Chastanet, S. Qazi, K. Sorensen, P. Hill, T. Msadek, and H. Ingmer. 2004. Clp ATPases are required for stress tolerance, intracellular replication and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1445-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frees, D., S. N. Qazi, P. J. Hill, and H. Ingmer. 2003. Alternative roles of ClpX and ClpP in Staphylococcus aureus stress tolerance and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1565-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frees, D., L. E. Thomsen, and H. Ingmer. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus ClpYQ plays a minor role in stress survival. Arch. Microbiol. 183:286-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu, Z., N. P. Donegan, G. Memmi, and A. L. Cheung. 2007. Characterization of MazFsa, an endoribonuclease from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 189:8871-8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu, Z., S. Tamber, G. Memmi, N. P. Donegan, and A. L. Cheung. 2009. Overexpression of MazFsa in Staphylococcus aureus induces bacteriostasis by selectively targeting mRNAs for cleavage. J. Bacteriol. 191:2051-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerdes, K., S. K. Christensen, and A. Lobner-Olesen. 2005. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes, F. 2003. Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest. Science 301:1496-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horsburgh, M. J., J. L. Aish, I. J. White, L. Shaw, J. K. Lithgow, and S. J. Foster. 2002. σB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 184:5457-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings, L. D., D. S. Lun, M. Medard, and S. Licht. 2008. ClpP hydrolyzes a protein substrate processively in the absence of the ClpA ATPase: mechanistic studies of ATP-independent proteolysis. Biochemistry 47:11536-11546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kullik, I., P. Giachino, and T. Fuchs. 1998. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor σB in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4814-4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehnherr, H., and M. B. Yarmolinsky. 1995. Addiction protein Phd of plasmid prophage P1 is a substrate of the ClpXP serine protease of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:3274-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemos, J. A., T. A. Brown, Jr., J. Abranches, and R. A. Burne. 2005. Characteristics of Streptococcus mutans strains lacking the MazEF and RelBE toxin-antitoxin modules. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lithgow, J. K., E. Ingham, and S. J. Foster. 2004. Role of the hprT-ftsH locus in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 150:373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loris, R., I. Marianovsky, J. Lah, T. Laeremans, H. Engelberg-Kulka, G. Glaser, S. Muyldermans, and L. Wyns. 2003. Crystal structure of the intrinsically flexible addiction antidote MazE. J. Biol. Chem. 278:28252-28257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowy, F. D. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnuson, R. D. 2007. Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems. J. Bacteriol. 189:6089-6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majerczyk, C. D., M. R. Sadykov, T. T. Luong, C. Lee, G. A. Somerville, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus CodY negatively regulates virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 190:2257-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manna, A., and A. L. Cheung. 2001. Characterization of sarR, a modulator of sar expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:885-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran, G. J., A. Krishnadasan, R. J. Gorwitz, G. E. Fosheim, L. K. McDougal, R. B. Carey, D. A. Talan, and the EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. 2006. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:666-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieto, C., I. Cherny, S. K. Khoo, M. G. de Lacoba, W. T. Chan, C. C. Yeo, E. Gazit, and M. Espinosa. 2007. The yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin systems of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae: functional and structural correlation. J. Bacteriol. 189:1266-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novick, R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan, Q., and R. Losick. 2003. Unique degradation signal for ClpCP in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:5275-5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pandey, D. P., and K. Gerdes. 2005. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:966-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prepiak, P., and D. Dubnau. 2007. A peptide signal for adapter protein-mediated degradation by the AAA+ protease ClpCP. Mol. Cell 26:639-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts, R. C., A. R. Strom, and D. R. Helinski. 1994. The parDE operon of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 specifies growth inhibition associated with plasmid loss. J. Mol. Biol. 237:35-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenk, S., and R. A. Laddaga. 1992. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 73:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor, M. D., and L. M. Napolitano. 2004. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in vascular surgery: increasing prevalence. Surg. Infect. 5:180-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Melderen, L., M. H. Thi, P. Lecchi, S. Gottesman, M. Couturier, and M. R. Maurizi. 1996. ATP-dependent degradation of CcdA by Lon protease. Effects of secondary structure and heterologous subunit interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27730-27738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshizumi, S., Y. Zhang, Y. Yamaguchi, L. Chen, B. N. Kreiswirth, and M. Inouye. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus YoeB homologues inhibit translation initiation. J. Bacteriol. 191:5868-5872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]