Abstract

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of the conserved multifunctional transcription factor CTCF was previously identified as important to maintain CTCF insulator and chromatin barrier functions. However, the molecular mechanism of this regulation and also the necessity of this modification for other CTCF functions remain unknown. In this study, we identified potential sites of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation within the N-terminal domain of CTCF and generated a mutant deficient in poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Using this CTCF mutant, we demonstrated the requirement of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation for optimal CTCF function in transcriptional activation of the p19ARF promoter and inhibition of cell proliferation. By using a newly generated isogenic insulator reporter cell line, the CTCF insulator function at the mouse Igf2-H19 imprinting control region (ICR) was found to be compromised by the CTCF mutation. The association and simultaneous presence of PARP-1 and CTCF at the ICR, confirmed by single and serial chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, were found to be independent of CTCF poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. These results suggest a model of CTCF regulation by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation whereby CTCF and PARP-1 form functional complexes at sites along the DNA, producing a dynamic reversible modification of CTCF. By using bioinformatics tools, numerous sites of CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization were demonstrated, suggesting that such regulation of CTCF may take place at the genome level.

CTCF is a highly conserved transcription factor which recognizes and binds to various target DNA sequences (28, 31, 54, 72). Different regulatory roles performed by CTCF include promoter activation (33, 86) or repression (32), hormone-responsive gene silencing (16), regulation of cell growth and proliferation (77, 84), differentiation (56, 61, 83), and apoptosis (26). CTCF is also involved in the regulation of methylation-dependent chromatin insulation (11, 42) and chromatin barrier functions (22, 49, 91) and genomic imprinting (10). From these perspectives, the best-studied example is provided by the Igf2-H19 imprinted locus, where CTCF binds to the imprinting control region (ICR) on the maternal allele and creates a chromatin insulator boundary between the Igf2 gene promoters and enhancers downstream of the H19 gene. Methylation of the paternally inherited ICR DNA sequence silences the H19 promoter and enables Igf2 transcription by preventing CTCF binding to the insulator (10, 42, 46, 82).

CTCF functions depend on interactions with various proteins (88) and posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation (29, 53), SUMOylation (64), and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) (18, 52). In particular, PARylation was found previously to regulate CTCF insulator (92) and chromatin barrier (91) functions and also affects the transcription of rRNA (84).

PARylation is a covalent modification of proteins catalyzed by the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), a large family of 18 proteins encoded by different genes (44, 80), of which the best-studied isoform is PARP-1 (6). Recent evidence, however, suggests that there may be only six true PARPs and that the remaining family members are mono(ADP-ribosyl)transferases (44, 51). The PARylation reaction involves a processive sequential transfer of ADP-ribose moieties from coenzyme NAD+ to an acceptor protein (44, 60). Although it is generally perceived that there is no specific consensus site for the PARylation reaction (43), it has been reported previously that glutamic and aspartic acid (3, 43) and lysine (4) residues of putative acceptor proteins can be utilized as ADP-ribose acceptor sites. The catalyzed reaction results in an ADP-ribose polymer (PAR) chain of variable length, from a few to 200 ADP-ribose units, attached to the protein. This polymer chain may also be branched in structure, with a frequency of branching of 1 per 20 to 30 ADP-ribose residues (69). The modification is transient, as the PARs are rapidly degraded by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) or other proteins with phosphodiesterase activity (14, 37, 79).

It is well established that PARylation modulates the activities of PARP-1 and various nuclear proteins (21, 23, 57-59, 85, 87) and is implicated in DNA repair, recombination, cell proliferation, cell death, and the regulation of nuclear and chromatin functions (21, 44, 68, 80). Intriguingly, CTCF appears to act as a link between PARylation and DNA whereby CTCF activates PARP-1, leading to DNA hypomethylation (40).

Although we have gained knowledge from previous studies, the role of PARylation in the regulation of different CTCF functions and also mechanistic aspects of this regulation are still not well understood. In this investigation, we identified PARylation sites in CTCF and generated a mutant deficient in PARylation, which was employed to investigate the importance of CTCF PARylation in transcriptional regulation and the control of cell proliferation. Regulation of insulator function was also examined with a newly generated isogenic insulator reporter cell line. In all functional tests, we observed a loss of function of the non-PARylated CTCF. Our observation of PARylation-independent association of CTCF and PARP-1 at the mouse H19 ICR, in the new isogenic insulator system, led to a model whereby PARP-1 (and possibly PARG) molecules form functional complexes with CTCF at sites on DNA. We suggest that PARylation and de-PARylation of CTCF are dynamic processes in response to cellular signals and/or the environment and are an essential mechanism in the regulation of CTCF function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and transfections.

Human cell lines used in this study were HeLa (cervical carcinoma) and 293T (embryonic kidney) cells and B4 cells (transgenic 293T cells; see the next section), all maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with l-glutamine, glucose pyridoxine-HCl, and NaHCO3 (Lonza), and MDA435 (breast carcinoma) and MCF7 (breast carcinoma) cells, maintained in RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine (Lonza). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest) and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Invitrogen). Transient transfections of cell lines were carried out using a calcium phosphate transfection protocol (26). The β-galactosidase expression construct pCH110 (Invitrogen) was used for normalization of the transfection efficiency.

Stable isogenic insulator reporter cell line B4.

B4 cells were generated by stable transfection of 293T cells with a luciferase-neomycin resistance (luciferase-neo) construct. The construct contains a luciferase gene under the control of the mouse Igf2 promoter (P3), an H19 enhancer, and the upstream H19 ICR. The construct also contains a cytomegalovirus promoter-driven neomycin resistance gene (see Fig. 4A), which enabled selection for active neo transcription. To obtain single-construct integration, the neomycin-resistant cells were subjected to limiting dilution to enrich for clones from single colonies. Single-copy integration of the luciferase-neo construct was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), and the methylation status of the CTCF binding sites was also verified (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

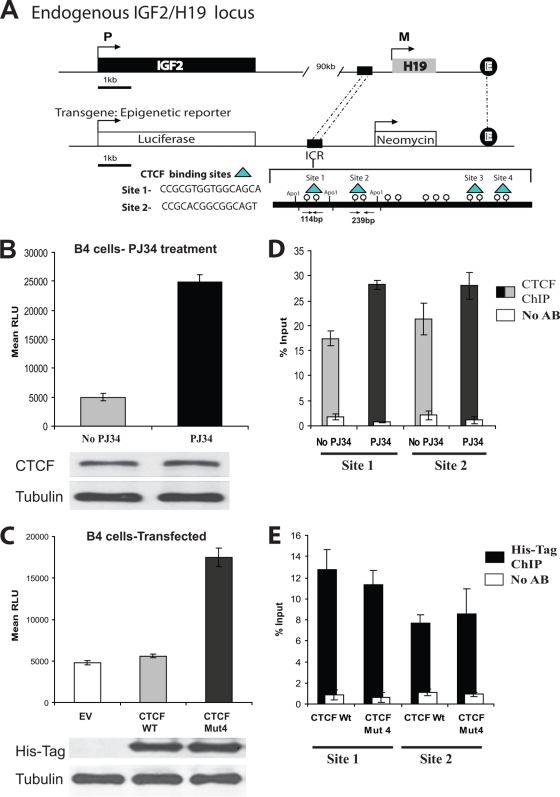

FIG. 4.

CTCF insulator function at the H19 ICR in a transgenic model is dependent on PARylation. (A) In vitro epigenetic reporter system: a schematic diagram of the stably integrated luciferase reporter construct in the 293T transgenic cell line B4. The integrated construct contains a luciferase gene under the control of the mouse Igf2 promoter (P3), an H19 enhancer, and the upstream H19 ICR. The ICR contains four identified binding sites for the CTCF protein (indicated). (B) The activity of the luciferase gene controlled by the Igf2 promoter is increased in the presence of the PARP inhibitor PJ34. B4 cells (6 × 105) were plated and either treated or not treated with 10 μM PJ34. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were counted and lysed and the luciferase assay was performed. The luciferase values were normalized based upon cell number. Bars represent luciferase activity in relative luciferase units (RLU). Each bar shows an average of results from three experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The levels of CTCF in the cell lysates were assessed by Western blotting using the anti-CTCF antibody. The membrane was reprobed with an antitubulin antibody as an internal control for cell number (results are shown at the bottom). (C) The activity of the luciferase gene controlled by the Igf2 promoter is increased in cells transfected with the vector expressing CTCF Mut4, which is deficient in PARylation. B4 cells (4 × 105) were transfected with 5 μg of either the EV or a vector expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut 4 and 0.5 μg of the β-galactosidase-expressing construct. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were counted, lysed, and subjected to the luciferase assay. The luciferase values were initially normalized by cell number, and the transfection efficiency was then normalized using the β-galactosidase assay. Bars represent luciferase activity in relative luciferase units. Each bar shows an average of results from three experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The levels of exogenous CTCF were assessed by Western blotting using the anti-His tag antibody. The membrane was reprobed with an antitubulin antibody as an internal control for cell number (results are shown at the bottom). (D) Endogenous CTCF is associated with the CTCF binding sites 1 and 2 at the H19 ICR in B4 cells not treated and treated with PJ34. B4 cells (5 × 106) were either treated or not treated with 10 μM PJ34 for 24 h, cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde, and the standard ChIP assay was performed to assess the in vivo CTCF occupancies at the DNA. To separate two CTCF binding sites, site 1 and site 2, the DNA-protein complexes were digested overnight with ApoI restriction endonuclease and subjected to IP with the anti-CTCF antibody. Real-time PCR amplification was carried out using primers situated within site 1 and site 2. The efficiency of ChIP at each of the sites was calculated as a percentage of the starting material (percent input). Results are a representative example of data from three independent experiments. (E) Exogenous CTCF is associated with the CTCF binding sites 1 and 2 at the H19 ICR in B4 cells transfected with the plasmids expressing the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4. B4 cells (5 × 106) were transfected with a plasmid expressing either the His-tagged CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde and the standard ChIP assay was performed to assess the in vivo occupancies at the DNA. To separate two CTCF binding sites, site 1 and site 2, the DNA-protein complexes were digested overnight with ApoI restriction endonuclease and subjected to IP with the anti-His tag antibody. Real-time PCR amplification was carried out using primers situated within site 1 and site 2. The efficiency of ChIP at each of the sites was calculated as a percentage of the starting material (percent input). Results are a representative example of data from three independent experiments.

The expression of the luciferase gene in the B4 cells was assessed by a luciferase assay. In all experiments, the luciferase values were normalized by cell number. This method was verified for reproducibility by using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega). The cell number was determined by counting (using untreated and untransfected cells) and confirmed by the CellTiter-Glo assay; between three and five replicate assays were performed.

Generation of the CTCF-expressing vectors and the CTCF mutants deficient in PARylation.

A CTCF expression construct was prepared by excision of the sequence encoding His-tagged CTCF from the vector for bacterial expression of CTCF, pET7.1 (7). The fragment containing CTCF cDNA was excised from pET7.1 by using XhoI and NheI and inserted into the eukaryotic expression vector pCi (Promega) digested with XhoI and XbaI. The resulting cloned expression vector produced a full-length His-tagged wild-type CTCF protein (CTCF WT).

Mutant CTCF expression vectors were produced by site-directed mutagenesis, using CTCF WT as a template, by the QuikChange method according to the instructions of the QuikChange manufacturer (Stratagene). The primers used in the generation of CTCF mutants were as follows: for CTCF mutant 1 (Mut1), forward primer 5′ GATGTGTCTGCGTACGATTTTGCGGCAGCACAGCAGGAGG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ CCTCCTGCTGTGCTGCCGCAAAATCGTACGCAGACACATC 3′; for Mut2, forward primer 5′ GCGTTATACAGCGGCGGGCAAAGATG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ CATCTTTGCCCGCCGCTGTATAACGC 3′; and for Mut3 and Mut4, forward primer 5′ ACAGCAGGCGGGTCTGCTATCAGCGGTTAATGCGGCGAAAGTGGTTG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ CAACACTTTCGCCGCATTAACCGCTGATAGCAGACCCGCCTGCTGT 3′.

The CTCF-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fusion constructs, both wild-type and mutant forms, were prepared by excision of the relevant CTCF constructs using XbaI and EcoRI and insertion of the fragments into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech). A p19ARF-luciferase gene reporter construct was used in the reporter assays, as described previously (33).

Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays.

The human cell lines were subjected to a luciferase reporter assay, following cotransfections and normalization of transfection efficiency by using a β-galactosidase assay, as described previously (66). The luciferase reporter assay kit was used to measure luciferase activity according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega).

BrdU assay.

Forty-eight hours posttransfection of 293T, HeLa, and MDA435 cells with either EGFP-CTCF WT or EGFP-CTCF mutants, cells were incubated with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) as described previously (35). Incorporation of BrdU by cells was visualized by incubation with anti-BrdU antibody (Sigma) and then a tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako), staining of cells with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), and fluorescence microscopy analysis. A minimum of 1,000 cells were assessed for proliferation based upon the incorporation of BrdU (red fluorescence) and positivity for EGFP (green fluorescence). An average percentage of proliferating cells from each experiment, carried out in triplicate and repeated three times, was calculated.

PARG assay.

The nucleoplasmic extracts from MCF7 cells (106), enriched with the CTCF-180 isoform (84), were obtained as described previously (92). The extracts were incubated with 1, 2, 3, or 5 mU of PARG enzyme (Axxora) as reported earlier (15). The incubated extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-CTCF antibody (Abcam).

Indirect immunostaining and analysis of colocalization of CTCF and PARP-1.

Cells were seeded for 48 h onto eight-well glass slides and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at −20°C. Blocking was performed for 2 h at room temperature with blocking solution containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Slides were then incubated simultaneously with anti-rabbit PARP-1 antibody (diluted 1:400; a gift from L. Kraus) and anti-mouse CTCF antibody (diluted 1:50; from BD Transduction Laboratories) at 4°C overnight. After three washes in PBS with gentle shaking (each at least 15 min), secondary antibodies labeled with Dylight 488 (green; anti-mouse antibody) and Dylight 594 (red; anti-rabbit antibody) (both from Thermo Scientific) were mixed, and the slides were incubated at room temperature for 2 h and then washed with PBS. Images for PARP-1 and CTCF were taken using the same exposure times for both red and green channels before using the colocalization module (Volocity; Improvision), which provides the facility to visualize proteins and quantify colocalization in a pair of images. The colocalization was calculated at the same voxel (volumetric pixel) locations in the two images; by using the same module, an overlay with a scatter plot including statistics with a Pearson coefficient was automatically generated (65).

ISPLA.

The in situ proximity ligation assay (ISPLA) was performed as described previously (34), with modifications. Briefly, cells were seeded for 48 h onto eight-well glass slides and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at −20°C. Cells were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with blocking solution containing 3% BSA and PBS. Both primary antibodies, anti-CTCF (BD Transduction Laboratories) and anti-PARP-1 (a gift from L. Kraus), were individually incubated in blocking solution for 15 min and then mixed together and applied to the slides, and the slides were incubated overnight at 4°C. The slides were washed four times with PBS for 15 min with gentle shaking. Proximity probes were covalently linked via their 5′ ends to affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies by using a hydrazone linker (SoluLinK, San Diego, CA). The donkey anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was linked to the nonpriming amine-modified oligonucleotide NH2-AAA AAA AAA AGA CGC TAA TAG TTA AGA CGC TT(U UU). Modified secondary antibodies were separately incubated in blocking solution for 15 min and then added to the slides, and the slides were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a humid chamber and washed with PBS four times, each for 15 min. Hybridization, ligation, and rolling-circle amplification were performed using the Duolink detection kit (Olink Bioscience). At the final step, when the detection solution is applied, NorthernLights-labeled secondary antibodies (R&D Systems) were also added to visualize the individual primary antibodies. Finally, six washes in PBS at room temperature for 15 min each were performed. Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken using a grid microscope and analyzed by the Volocity software (Improvision). Controls for ISPLA are shown in Fig. S7A in the supplemental material.

IP.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed as described previously (20). In brief, MCF7 cells (2 × 106) were lysed in 500 μl of IP buffer, composed of 25 mM Tris-HEPES (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Tween 20, 0.25 M NaCl, and protease inhibitors. The lysates were incubated for 4 h with either anti-PAR-10H mouse monoclonal antibody (Alexis) or anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal antibody (Calbiochem) and then incubated for 2 h with either protein G or protein A Sepharose Fast Flow beads. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting.

ChIP and re-ChIP (serial ChIP) assays.

A chromatin IP (ChIP) assay was performed as described previously (19), using B4 cells either treated or not treated with PJ34 and either untransfected or transfected with the pCi empty vector (pCi EV) or the vector expressing CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4. In this assay, 107 cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde. Instead of being subjected to the usual sonication method to fragment the DNA, the DNA-protein complexes were digested overnight at 37°C with the ApoI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs). In all ChIP experiments, the complete digestion of the cross-linked DNA by ApoI was assessed by PCR analysis of the input material using the site 1 forward primer and the site 2 reverse primer (see below) for amplification: absence of the product confirmed the efficiency of digestion (data not shown). The DNA-protein complexes were immunopurified using anti-His tag and anti-CTCF antibodies (75) (for endogenous CTCF) or anti-PARP antibody (Alexis) and protein A4 Sepharose Fast Flow beads (Sigma).

PCR amplification of the purified DNA was performed using primers corresponding to the selected DNA sites within the integrated H19 ICR, as follows: site 1, forward primer 5′ CAAGGAGACCATGCCCTA 3′ and reverse primer 5′GGGGGGCTCTTTAGGTTT 3′, and site 2, forward primer 5′ GCAGGACACATGCATTTT 3′ and reverse primer 5′ GACTAGCATGAACCCCTG 3′.

PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min; 33 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and 72°C for 3 min.

The re-ChIP assay was performed following the standard single ChIP assay (see above). For re-ChIP, the immunoprecipitates from the single ChIP were eluted with the buffer of 5 M urea-50 mM 2-β-mercaptoethanol, after which the precipitates were dialyzed against a solution of 10 mM Tris-HEPES (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100. Re-ChIP was performed with either the anti-His tag, anti-PARP-1, or antitubulin antibody and protein A or protein G4 Sepharose Fast Flow beads (Sigma). PCR amplification was performed using the purified DNA from either the single ChIP or the re-ChIP, primers corresponding to the selected DNA sites within the integrated H19 ICR, and the conditions described above for the single ChIP.

Real-time PCR analyses of the single-ChIP or re-ChIP samples were carried out in triplicate using 2 μl of the immunoprecipitated DNA sample or 2 μl of input DNA together with 200 nM primers diluted in a final volume of 25 μl of SensiMixPlus SYBR solution (Quantace). PCR conditions were per the instructions of the solution manufacturer. Primers used were as follows: site 1, forward primer 5′ AGACCATGCCCTATTCTTGG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ GCTCTTTAGGTTTGGCGC 3′; site 2, forward primer 5′ ACCCAAGTTCAGTACCTCAG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ TTTAGGACTGCGATGTACGA 3′; chromosome 7, forward primer 5′ AGAGACAAACTTAACAAGGAGG 3′ and reverse primer 5′ GCCATACATTTCAATCCCTG 3′; chromosome 11, forward primer 5′ GTTCTAGGAATCTCTGACATCG and reverse primer 5′ TCTGCTAACTCTGTTCACCAG 3′; and chromosome 21, forward primer 5′ CATCCTATGAAGTGAACTAAACAG and reverse primer 5′ CTTGCTCCTTTGATTCCTCC 3′.

Amplification, data acquisition, and analysis were carried out using a Chromo4 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The percentage of DNA brought down by ChIP (percent input) was calculated as follows: percent input = AE(CTinput − CTChIP) × Fd × 100, where AE is the amplification efficiency, CTChIP and CTinput are threshold cycle values obtained from the exponential phase of quantitative PCR, and Fd is a dilution factor for the input DNA to balance the difference in amounts of ChIP samples.

Western blot analysis.

Lysates from different cell lines were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (26). In brief, cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and probed with anti-CTCF (Abcam, Cambridge, Cambs, United Kingdom), anti-His tag (Cell Signaling), anti-PAR-10H mouse monoclonal (Alexis), anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal (Calbiochem), antibiotin (Sigma), anti-PARP (Alexis), anti-PARG (Abcam, Cambridge, Cambs, United Kingdom), and anti-α-tubulin (Sigma) antibodies. The secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies (both from Abcam) and anti-protein A-HRP (Sigma). Immunocomplexes were detected by using an ECL kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Bucks, United Kingdom).

Biotinylated-NAD labeling and selection of labeled proteins.

To confirm the modification of CTCF by PARylation, nonradioactive labeling of cells with 6-biotin-17-NAD (biotinylated NAD+), which results in the incorporation of biotinyl-ADP-ribose into acceptor proteins, was used. MCF7 cells (7.5 × 105) were incubated with biotinylated NAD (Trevigen) as described previously (8). The cells were lysed in 500 μl IP buffer (see “IP” above), and labeled proteins were selected using Dynal M-280 streptavidin beads per the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen).

ChIP-on-ChIP data comparison to investigate the colocalization of CTCF and PARP-1.

A comparison of the microarray data obtained from two independent ChIP-ChIP experiments was made. The two chosen data sets both contained data from genome binding/occupancy profiling using tiling arrays featuring the ENCODE regions and therefore enabled a direct comparison of the data. The data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). As input for CTCF ChIP localization analysis, we used the statistically processed data deposited under accession number GSM52941 (ChIP-ChIP data for CTCF in HL60 cells) (13). For PARP-1 input, we used raw data supplied under accession numbers GSM239063 and GSM239064 (ChIP-ChIP data for PARP-1 in MCF7 cells) (59) that have been statistically processed in a way similar to data for CTCF (13) to make them comparable. In brief, a two-tailed ranked Wilcoxon test was used to compare probes in each IP versus input conditions in a 1,000-bp sliding window with 250-bp steps. A −10 log10 P value and a Hodges-Lehmann estimator were determined for each window. Chromosome coordinates corresponding to statistically significant P values for both CTCF and PARP-1 ChIP data were compared. The colocalization region was considered when CTCF and PARP-1 positions, expressed in chromosome coordinates, were within 500 bp of each other. The colocalization sites were mapped to the relevant human chromosomes to obtain a hot spot map.

Mass spectrometry.

Samples were loaded onto a thin SDS-PAGE gel, and the affinity-purified proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed as described earlier (19). In brief, the band of interest was excised and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion, and the tryptic peptides were subsequently extracted and analyzed using a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry ion trap (Esquire; Bruker Daltonics). Ion searching was performed using both in-house-built Mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com) and the X!Tandem tandem mass spectrometry search tool (http://thegpm.org) with SwissProt database release 57.8.

RESULTS

CTCF-130 and CTCF-180 are differentially poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated.

It has been generally assumed that CTCF is a protein with the apparent molecular mass of 130 kDa (CTCF-130), found predominately in the nuclear extracts of cells (26, 55). A further form of CTCF that migrated at 180 kDa (CTCF-180) and carried a PARylation mark was later reported (84, 92). We verified this modification in a PARG enzyme assay using MCF7 cell nucleoplasmic extracts enriched with CTCF-180 following treatment with sodium butyrate (15). In this experiment, a shift from CTCF-180 to CTCF-130 was observed with increasing doses of PARG, suggestive of the removal of the PARylation mark from CTCF-180 by PARG (Fig. 1A). We anticipated the presence of intermediate forms of CTCF following treatment with PARG, due to the nature of PARylation. However, only discrete forms of CTCF (CTCF-180 and CTCF-130) were detected.

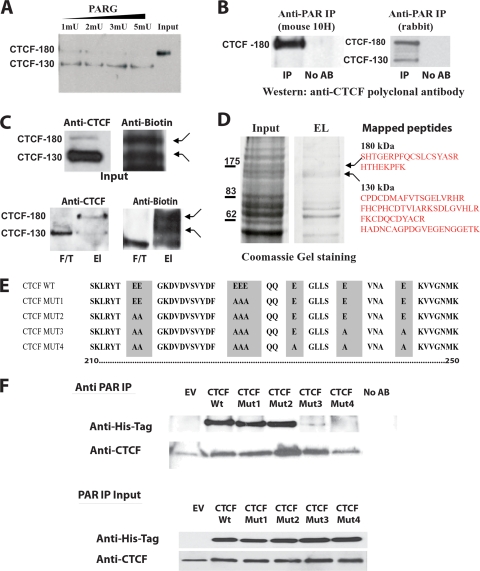

FIG. 1.

CTCF-180 and CTCF-130 are differentially poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated. (A) Removal of PARylation from CTCF-180 using PARG. MCF7 cell nucleoplasmic extracts containing only CTCF-180 were incubated with PARG enzyme in a dose-dependent manner. The incubated lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-CTCF polyclonal antibody (Abcam). A complete shift from CTCF-180 to CTCF-130 is observed following increases in units of PARG. (B) The anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal antibody and mouse 10H antibody immunoprecipitate specific forms of CTCF. MCF7 cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with either the anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal antibody or anti-PAR mouse (10H) antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-CTCF polyclonal antibody. (Left) The anti-PAR mouse 10H antibody, which recognizes more than 20 PAR residues, immunoprecipitates only CTCF-180. (Right) The anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal antibody is able to recognize as few as two PAR residues and is able to immunoprecipitate both CTCF-130 and CTCF-180. No AB, control with no antibody in the IP reaction mixture. (C) Labeling with biotinylated NAD+ reveals two forms, CTCF-180 and CTCF-130. MCF7 cells (7.5 × 105) were incubated with biotinylated NAD+, leading to the incorporation of biotinylated ADP-ribose residues attached to protein acceptors. The labeled proteins were selected using M-280 streptavidin magnetic beads. (Top) The input was analyzed for the presence of the CTCF forms by a Western blot assay. The membrane was probed with the anti-CTCF rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam), stripped, and probed with antibiotin antibody. Both CTCF-130 and CTCF-180 forms were present in the extracts (left), and bands of similar sizes (indicated by arrows) were observed when the membrane was probed with the antibiotin antibody (right). (Bottom) For selected biotinylated proteins, the elution (El) and flowthrough (F/T) fractions were analyzed by a Western blot assay for the presence of CTCF. (Left) CTCF-130 appears in both fractions, whereas CTCF-180 is observed only in the elution fraction. (Right) The membrane was stripped and reprobed with the antibiotin antibody to confirm the presence of similarly sized labeled bands (indicated by arrows). (D) Analysis of the 130- and 180-kDa bands of the PARylated proteins selected using M-280 streptavidin magnetic beads and mass spectrometry. Proteins eluted from streptavidin magnetic beads were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Bands corresponding to 130 and 180 kDa were excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The identified CTCF peptides are shown. (E) Schematic diagram of the CTCF N-terminal domain amino acid sequence showing the mutations produced by site-directed mutagenesis. The wild-type sequence is depicted at the top. Amino acid substitutions are highlighted. The amino acids are numbered according to Filippova et al. (32). (F) Western blot analysis of the proteins produced by the mutant variants of CTCF. 293T cells were transfected with 5 μg of EV or a vector expressing the CTCF WT or a CTCF mutant. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were lysed and the cell extracts were divided in two and either subjected to IP with the anti-PAR rabbit polyclonal antibody or used as an input control. (Top) The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the anti-His tag antibody. The membrane was reprobed with an anti-CTCF antibody, confirming the presence of endogenous CTCF-130, retained by the anti-PAR antibody, in all cell lysates. (Bottom) The input materials were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with both the anti-His tag antibody and anti-CTCF, showing equal amounts of the exogenous and endogenous CTCF proteins.

Findings from studies using in vitro PARylation and IP with the mouse monoclonal 10H anti-PAR antibody had suggested that CTCF-180 was the PARylated form (92). This antibody recognizes only linear PAR chains of more than 20 PAR residues (47). We reasoned that if CTCF contains less than 20 residues of PAR, it is unlikely to be detected with this antibody. In the present investigation, we refined this analysis to further assess the two CTCF forms with regard to the level of PARylation by using the rabbit polyclonal anti-PAR antibody, which recognizes as few as two PAR residues and has higher affinities for longer chain lengths (1). We compared the two anti-PAR antibodies, monoclonal 10H and rabbit polyclonal, in IP experiments using MCF7 cell lysates and then performed Western analysis with the anti-CTCF polyclonal antibody. This experiment revealed that both CTCF-180 and CTCF-130 were present in the sample immunoprecipitated with the rabbit anti-PAR polyclonal antibody but that only CTCF-180 was present in the sample immunoprecipitated with the monoclonal 10H anti-PAR antibody (Fig. 1B).

To confirm the modification of CTCF by PARylation, MCF7 cells were labeled with biotinylated NAD+ and the lysates were subjected to Western blotting using either the anti-CTCF or the antibiotin antibody. With the use of the antibiotin antibody, two proteins were observed whose sizes coincided with CTCF-180 and CTCF-130 identified in the same lysates with the polyclonal anti-CTCF antibody (Fig. 1C, top). The labeled samples were then purified using M-280 streptavidin magnetic beads, which selected proteins containing biotinyl-ADP-ribose residues. As shown in Fig. 1C (bottom), two bands coincided with CTCF-180 and CTCF-130 identified in the same lysates with the polyclonal anti-CTCF antibody.

To confirm the presence of CTCF-130 and CTCF-180 among the proteins migrating as 130 and 180 kDa, the proteins labeled with biotinylated NAD+ and selected using streptavidin beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue; bands corresponding to 130- and 180-kDa proteins were excised from the gel (Fig. 1D). The gel slices were subjected to in-gel digestion, and peptides were extracted and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Database searching with the recovered peptide sequences showed that sequences from both the 130- and 180-kDa bands matched human CTCF (Swiss-Prot protein database accession number P49711); these peptide sequences are presented in Fig. 1D (right).

From the results of these experiments, we conclude that both forms of CTCF were PARylated, with CTCF-130 containing from 1 to several ADP-ribose residues and CTCF-180 containing more than 20 ADP-ribose residues.

Production of a series of CTCF mutants deficient in poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation.

Next, we aimed to generate a CTCF variant deficient in PARylation. It is generally accepted that there is no consensus site for PARylation (25); therefore, the following experimental observations were considered to determine the possible PARylated sequences in CTCF. First, we discovered that the N-terminal domain of CTCF was modified by PARylation in the in vitro PARylation assay (92). Second, by using a combination of alkaline hydrolysis of CTCF produced in baculovirus and mass spectrometry, a PAR-modified peptide was identified in the N-terminal domain (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). This peptide is highly conserved among species (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material) and is also rich in glutamic acids, which we propose comprises possible PARylation sites (Fig. 1E).

This information was used to generate a series of CTCF mutants. The glutamic acid residues of the His-tagged CTCF expressed by the pCi vector were replaced by alanine residues by sequential site-directed substitutions until a mutant deficient in PARylation (CTCF Mut4) was obtained. The mutants were produced in the following order: CTCF Mut1, CTCF Mut2, CTCF Mut3 (an unexpected mutant identified following sequencing of Mut4), and CTCF Mut4 (Fig. 1E). Each mutant was characterized for the presence of the PARylation mark in transfection experiments with either the CTCF WT or mutant CTCF, followed by IP experiments using the polyclonal anti-PAR antibody (Fig. 1F). Western analysis using an anti-His tag antibody revealed that CTCF Mut1 and CTCF Mut2 could be immunoprecipitated by the anti-PAR antibody, whereas only trace amounts of CTCF Mut3 and no CTCF Mut4 variants were detected (Fig. 1F, top). Thus, CTCF Mut4 was the only exogenous CTCF protein that did not carry a PARylation mark. The membrane was then reprobed with an anti-CTCF antibody; this experiment confirmed that endogenous CTCF-130 proteins in all samples were equally and efficiently immunoprecipitated (Fig. 1F, top). The results also implied that a population of the endogenous CTCF-130 carried a PARylation mark, although this was likely to be short. Western analysis of the input material confirmed the presence of the exogenous CTCF in the samples (Fig. 1F, bottom). The generated mutants did not show any difference from the CTCF WT in their nuclear distribution/localization, stability, and levels of expression in the cell (Fig. 1F and data not shown).

We therefore concluded that CTCF Mut4 is a non-PARylated CTCF protein, which can be used in functional tests as a dominant negative mutant.

Inhibition of PARylation by PJ34 and PARylation deficiency of a CTCF mutant compromise CTCF functions as a transcriptional regulator and suppressor of cell proliferation.

CTCF is a transcriptional factor that negatively regulates cell proliferation (33, 77, 83). To examine how inhibition of PARylation affects transcription, we employed transient reporter assays with three cell lines of different tissue origins, 293T, MDA435, and HeLa, using a luciferase gene driven by the p19ARF promoter activated by the CTCF WT (33).

In the first series of experiments, cotransfections were carried out using either the CTCF WT or an EV and cells were treated with PJ34, a potent PARP inhibitor. The concentration of 10 μM PJ34 was found to be optimal for all three cell lines, with no effect on proliferation observed (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, at this concentration, PJ34 was found to effectively reduce general PARylation of proteins in these cell lines following oxidative stress caused by hydrogen peroxide (data not shown). As expected, activation of the p19ARF promoter by the CTCF WT was observed in all cell lines; however, this activation was considerably reduced in cells treated with PJ34 (Fig. 2A). The luciferase reporter system was also used to examine the effects of the mutated non-PARylated version of CTCF (CTCF Mut4). CTCF Mut4 showed reduced ability to activate the p19ARF promoter in comparison with the CTCF WT, although equivalent amounts of the protein were generated from the expression vectors in all three cell lines (Fig. 2B). Other CTCF mutants (Mut1, Mut2, and Mut3) were also used in this reporter assay, but no marked reduction in activation of the p19ARF promoter was observed (data not shown).

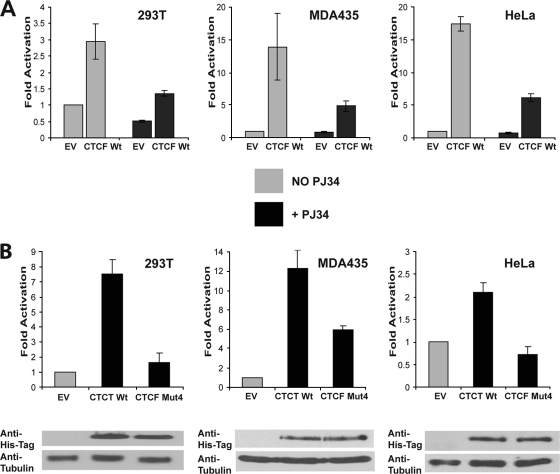

FIG. 2.

Activation of the p19ARF promoter by CTCF is poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation dependent. (A) Activation of the p19ARF promoter is abrogated by PJ34, a PARP inhibitor. 293T, MDA435, and HeLa cells were cotransfected with 2 μg of the luciferase reporter construct driven by the p19ARF promoter and either 0.5 μg EV or 0.5 μg of a CTCF WT-expressing plasmid; 0.5 μg of the β-galactosidase vector was added for normalization. Transfected cells were either treated or not treated with PJ34 (10 μM), and luciferase expression was quantified by a luciferase assay. Luciferase values were normalized using a β-galactosidase assay. The CTCF WT significantly activates the p19ARF promoter in the untreated cells, but following treatment with PJ34, the luciferase expression is greatly reduced. The loss of activation by the CTCF WT following PJ34 treatment is observed in all cell lines. Bars represent luciferase activity. Each bar shows an average of results from three experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Activation of the p19ARF promoter is abrogated by the CTCF mutant deficient in PARylation (CTCF Mut4). The 293T, MDA435, and HeLa cell lines were transfected with 0.5 μg of either an EV or a vector expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4, together with 2.0 μg of the p19ARF-luciferase reporter construct and 0.5 μg of a β-galactosidase expression vector. A luciferase assay of the transfected cells was performed, and values were normalized for transfection efficiency by using a β-galactosidase assay. The p19ARF promoter is activated by the CTCF WT, but reduced activation by CTCF Mut4 is observed. Bars represent luciferase activity. Each bar shows an average of results from three experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The levels of exogenously produced CTCF in the transfected cell lysates were assessed by Western blot analysis using the anti-His tag antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an antitubulin antibody used as a loading control. The results of the Western blot analysis are shown at the bottom.

We then asked whether the changes in CTCF Mut4 would compromise CTCF function as an inhibitor of cell proliferation. To investigate this issue, the EGFP-CTCF fusion proteins, both wild type and Mut4, were generated and utilized in a BrdU cell proliferation assay with three cell lines, 293T, MDA435, and HeLa. Following transfection with an EV expressing EGFP (the control) or a vector expressing EGFP-CTCF WT or EGFP-CTCF Mut4, the percentage of EGFP-positive proliferating cells was assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A). In all cell lines, inhibition of proliferation by the CTCF WT, but not CTCF-Mut4, was observed. Figure 3B shows a representative example of results from the BrdU assay carried out with the MDA435 cell line.

FIG. 3.

The poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of CTCF is important for the growth suppression and proliferation functions. (A) The mutant of CTCF deficient in PARylation (CTCF Mut4) abrogates CTCF function as a negative regulator of progression into S phase. To assess the number of cells in S phase, the BrdU assay was performed with 293T, MDA425, and HeLa cells transfected with 2.0 μg of either pEGFP-C1 (EV) or a plasmid expressing EGFP-CTCF WT or EGFP-CTCF Mut4. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were incubated with BrdU reagent for 2 h. The cells were fixed and stained with the anti-BrdU antibody as described in Materials and Methods. A secondary anti-mouse TRITC-conjugated antibody, together with DAPI, was used to visualize proliferating cells. A growth-suppressive effect on all cell lines transfected with the CTCF WT plasmid compared to those transfected with the EV was observed. In contrast, transfection of the cells with the CTCF Mut4 plasmid had no marked effect on cell proliferation. Each bar shows an average of results from three experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Fluorescence images of BrdU assay results for cells transfected with pEGFP-C1 (EV) or the plasmid expressing EGFP-CTCF WT or EGFP-CTCF Mut4. Following the BrdU assay as described above, the cells were visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Arrows indicate cells which are both EGFP-CTCF positive and proliferating (BrdU positive). A reduced number of proliferating cells is observed following transfection with the EGFP-CTCF WT vector, indicating a growth suppression effect. This growth-suppressive effect is not observed in the cells transfected with the EGFP-CTCF Mut4 vector, which show proliferation similar to that of the control cells (those transfected with the EV).

Of note, the EGFP fusion constructs were functionally and biochemically equivalent to their nonfusion counterparts, as determined by several criteria: (i) similar patterns of regulation of the reporter construct (p19ARF-luciferase reporter gene) in a reporter assay, (ii) identical patterns of distribution in the nucleus, and (iii) similar amounts of the fusion proteins, as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3B and data not shown).

From the results of these experiments, we concluded that deficiency in PARylation compromises CTCF functions as a transcriptional regulator and also as a suppressor of cell proliferation.

Inhibition of PARylation by PJ34 and PARylation deficiency of a CTCF mutant compromise the CTCF insulator function in a cell-based epigenetic system and in an endogenous system.

In our study, the insulator function of CTCF at the Igf2-H19 locus was examined using a novel isogenic insulator reporter cell model (a stable exogenous insulator system, or epigenetic system). The insulator reporter cell line was generated by stable transfection of 293T cells with a construct containing a luciferase gene regulated by the mouse Igf2-H19 insulator sequence, an enhancer, and Igf2 promoter 3 (yielding B4 cells) (Fig. 4A). The rationale for the generation of such a system was to create a quantifiable assay for insulator function that did not require colony counting. Investigation of the endogenous Igf2-H19 locus is impeded by a number of factors: (i) Igf2 is expressed at low levels in most normal cell lines; (ii) cancer cell lines often have rearrangements at the locus, and therefore, results obtained by assaying Igf2 expression after transfection with CTCF mutants are difficult to interpret; (iii) primary cell lines are not always available, and transfection of primary cell lines is difficult; (iv) many cell lines do not have the appropriate polymorphisms to detect the parent from which the expressed Igf2 allele originates; and (v) the endogenous Igf2 mRNA levels are influenced by RNA stability, multiple promoters, and posttranscriptional processing. We developed the stable exogenous insulator system which was devoid of these deficiencies and therefore used in our tests.

Prior to our experiments, this system was thoroughly assessed. Single-copy integration of the luciferase-neo construct was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (see Fig. S3A, B, and C in the supplemental material). Since CTCF binds only the maternal unmethylated Igf2-H19 ICR in order to exhibit its insulator function (46), the DNA methylation status of the integrated H19 ICR was inspected. Bisulfite sequence analysis revealed that a length of the DNA of the H19 ICR containing all four CTCF binding sites was unmethylated (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). ChIP analysis confirmed that CTCF is bound to the exogenous insulator sequence (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the epigenetic system is an adequate model for the maternal allele of the Igf2-H19 locus.

Luciferase assays were carried out following treatment of B4 cells with PJ34, and a comparison between treated and untreated cells was made. We assumed that the endogenous CTCF bound to the transgenic insulator sequence would function in its PARylated form to reduce expression of luciferase. Indeed, cells treated with PJ34 showed almost fivefold-higher levels of luciferase activity than untreated cells (Fig. 4B, top). Levels of CTCF in treated and untreated cells were found to be similar (Fig. 4B, bottom).

In order to assess the effects of non-PARylated exogenous CTCF in this model system, we transfected B4 cells with either the EV (control) or a plasmid expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4. The transfections were optimized to ensure that saturation with the exogenous CTCF had occurred to reduce any effects from endogenous CTCF (data not shown). Similar levels of luciferase expression were seen in the cells transfected with the EV and those transfected with the CTCF WT vector; however, the luciferase expression was considerably increased in cells transfected with the plasmid expressing CTCF Mut4 (Fig. 4C, top). Similar levels of the exogenous CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 were confirmed using Western analysis (Fig. 4C, bottom).

We then asked if the observed effects on luciferase expression following treatment with PJ34 and/or transfection were dependent on the binding of the exogenous CTCF to the H19 ICR. CTCF binding to two established binding sites for CTCF, designated site 1 and site 2 (82), was tested; these sites are both flanked by ApoI restriction enzyme sites and therefore could be easily separated and assessed for CTCF binding to each site (Fig. 4A).

ChIP experiments using anti-CTCF antibodies with both PJ34-treated and untreated B4 cells revealed enrichment at both binding sites and additionally in both treated and untreated cells in comparison with the controls (Fig. 4D; see also Fig. S5A in the supplemental material).

ChIP experiments were also carried out using B4 cells transfected with the vector expressing His-tagged CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4, and the anti-His tag antibody was used to select for only the bound exogenous CTCF. Results showed enrichment with both the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 at both binding sites (Fig. 4E; see also Fig. S5B in the supplemental material), thereby confirming that exogenous CTCF was bound to site 1 and site 2 at the H19 ICR, having replaced the endogenous protein.

The effects of PARylation inhibition and the expression of CTCF Mut4 on the endogenous Igf2-H19 locus were then tested using A911M and A911P mouse-human hybrid cells, which contain a single copy of human chromosome 11 of known parental origin (maternal or paternal) (67). The imprinted status is maintained in both cell lines, with monoallelic expression of IGF2 observed in A911P cells (those with the paternal chromosome) but not in A911M cells (those with the maternal chromosome) (67). Both cell lines were either treated with PJ34 or transfected with the EV or a vector expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4, and the expression level of IGF2 was assessed by real-time PCR. Expression of IGF2 was detected in A911P cells under all conditions, whereas in A911M cells (those with the maternal chromosome), IGF2 expression was observed only following treatment with PJ34 or transfection with the CTCF Mut4 plasmid (see Fig. S5C in the supplemental material).

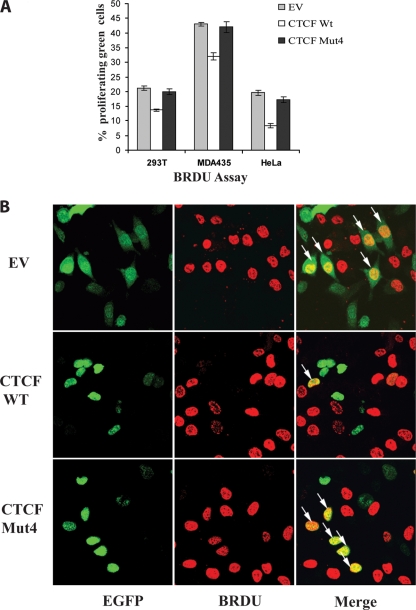

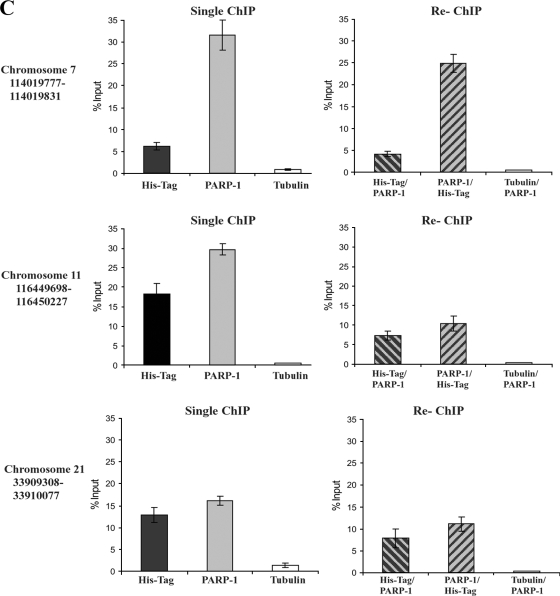

CTCF and PARP-1 colocalize at the CTCF binding sites.

Our results support a model described in previous reports (52, 92) which proposes a mechanism of epigenetic control based on reversible PARylation of CTCF bound to DNA. In this model, the PARylated CTCF at the H19 ICR represents the default state and functions as a constitutive insulator protein; the de-PARylated CTCF remains bound to DNA, but its function as an insulator is compromised. However, although CTCF was reported previously to interact with PARP-1 (93), it had not been determined whether PARP-1 and CTCF were associated with the same DNA sequences. To experimentally test this proposition, we first asked whether PARP-1 (endogenous), CTCF (exogenous), and PARG (endogenous) are all associated at the exogenous insulator in B4 cells. We performed coimmunoprecipitation/Western analyses using B4 cells transfected with a plasmid expressing either the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4 (non-PARylated). Anti-PARP-1 or anti-His tag antibodies were used for IP. As shown in Fig. 5A, endogenous PARP-1 is associated with both the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 (non-PARylated), but endogenous PARG was not detected in the immunoprecipitated complexes. No signal was detected in the control samples.

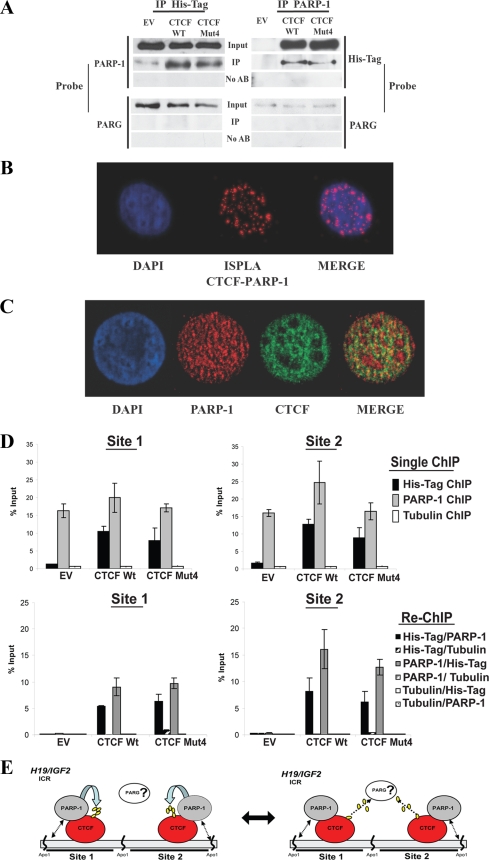

FIG. 5.

CTCF association with PARP-1 provides a mechanism of CTCF functional regulation by PARylation at the H19 ICR and genomewide. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis demonstrating that the association of PARP-1 with CTCF is independent of the CTCF PARylation status. B4 cells (2 × 106) were transfected with either the pCi EV or a vector expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4 and lysed for IP. The cell lysates were incubated with either the anti-PARP-1 or anti-His tag antibody for 4 h and then with protein A Sepharose Fast Flow for 2 h. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. The membranes were probed with either the anti-His tag or anti-PARP-1 antibody and sequentially with an anti-PARG antibody. (B) Analysis of CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization by ISPLA. The ISPLA was carried out with MCF7 cells by using both CTCF and PARP-1 antibodies. The red signal observed, as shown in the ISPLA image (center), indicates that CTCF and PARP-1 protein are in close proximity to each other, at a maximum distance of 40 nm or overlapping. DAPI staining and merging of images illustrate the extent of CTCF and PARP-1 nuclear colocalization. (C) Immunofluorescence staining demonstrating CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization. MCF7 cells were fixed and analyzed by dual immunofluorescence staining using both CTCF (green) and PARP-1 (red) antibodies. Nuclei are visualized by DAPI (blue); the merge of the green and red colors in shown in the rightmost image. (D) PARP-1 is associated with both the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 at CTCF binding sites 1 and 2 at the H19 ICR in B4 cells, as shown by results from ChIP and re-ChIP assays. B4 cells (5 × 106) were transfected with either the pCi EV or a plasmid expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4 and cross-linked with formaldehyde. A standard ChIP assay was followed by an additional elution step and re-ChIP to assess the in vivo occupancies of the DNA target sites by PARP-1, the CTCF WT, and CTCF Mut4. An antitubulin antibody was used as the negative control in both the ChIP and re-ChIP experiments. Real-time PCR amplification was carried out using primers situated within site 1 and site 2. The efficiency of ChIP at each of the sites was calculated as a percentage of the starting material (percent input). Expression of the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 was assessed by Western blotting (data not shown). (E) Proposed model of the regulation of CTCF functions by PARylation. In this model, the close proximity of CTCF and PARP-1 proteins is suggested to provide a mechanism by which CTCF functional activity may be regulated. CTCF and PARP-1 form a functional complex at the CTCF target sites. (Left) PARP-1 modifies CTCF, thereby modulating CTCF function. (Right) This reaction may be reversed by PARG-1, which may also be associated with the CTCF-PARP-1 complex. Double-headed arrows between PARP-1 and DNA in both the left and right panels indicate that the association between CTCF and PARP-1 may be independent of whether PARP-1 is bound to the DNA.

The colocalization of the endogenous CTCF and PARP-1 was observed in nuclei of different cell types by using ISPLA (Fig. 5B; see also Fig. S7B in the supplemental material) and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5C and data not shown). In the latter analysis, the Pearson coefficient was 0.697, indicating good correlation between the staining patterns of the two proteins. However, these results also indicate that there are populations of CTCF and PARP-1 which are not colocalized, suggesting that only a subset of CTCF binding sites have the potential to recruit CTCF-PARP-1 complexes.

We then asked if both PARP-1 and CTCF are present at site 1 and site 2 of the H19 ICR. We first performed single ChIP assays using either the anti-PARP-1, anti-His tag, or antitubulin (control) antibody with transfected B4 cells. Following the single ChIP with the PARP-1 antibody, both sites could be specifically amplified from all samples, confirming the presence of PARP-1 at both sites (Fig. 5D; see also Fig. S6, upper panels, in the supplemental material). Single ChIP was also performed using the anti-His tag antibody, thereby selecting only the DNA-protein complexes containing exogenously expressed CTCF (WT and Mut4). Signals for both CTCF binding sites were detected in cells transfected with a plasmid expressing the CTCF WT or CTCF Mut4 but not in cells transfected with the EV. The results of the single ChIP experiments confirmed that PARP-1 and the PARylated and non-PARylated forms of CTCF are associated with both CTCF binding sites.

In order to confirm the simultaneous presence of PARP and CTCF (WT and Mut4) at the two CTCF binding sites, a re-ChIP assay was performed using combinations of anti-PARP-1, anti-His tag, and antitubulin (control) antibodies. As shown in Fig. 5D and Fig. S6 (lower panels) in the supplemental material, site 1 and site 2 could be specifically amplified from the samples subjected to re-ChIP. No signal was detected in the controls when the antitubulin antibody was used as the first antibody in the re-ChIP with either the anti-His tag or anti-PARP-1 antibody. These results confirmed the simultaneous association of PARP-1 with both the CTCF WT and CTCF Mut4 at the H19 ICR in B4 cells. Importantly, this association was not dependent upon the PARylation status of CTCF.

We therefore suggest a model in which CTCF forms a functional complex with PARP-1 at CTCF binding sites, independently of the PARylation state of CTCF. Such association between CTCF and PARP-1 will then allow dynamic reversible modification of CTCF by PARP-1, thus maintaining the PARylated state of CTCF and modulating CTCF function (Fig. 5E). It is possible that a PAR degradation enzyme, such as PARG, may also be present in this complex, although we were unable to prove it experimentally.

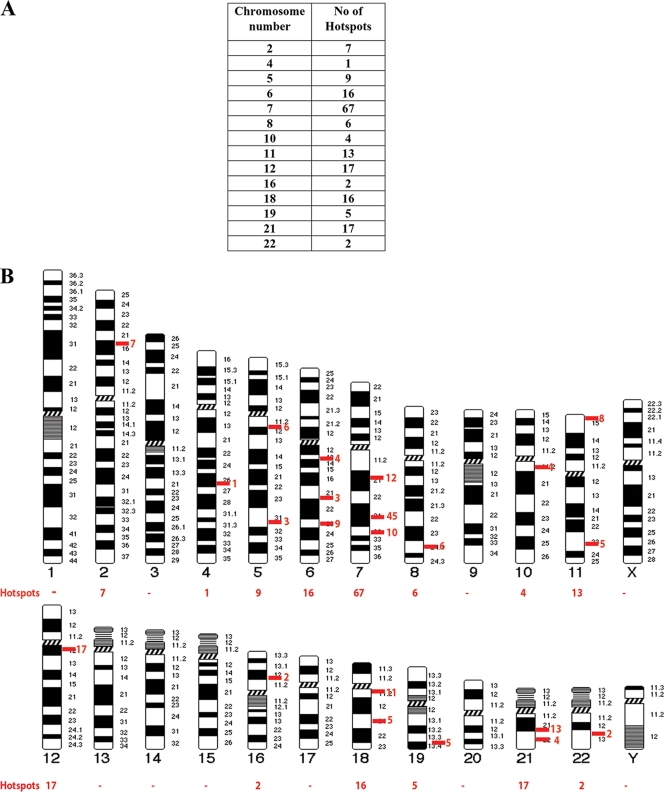

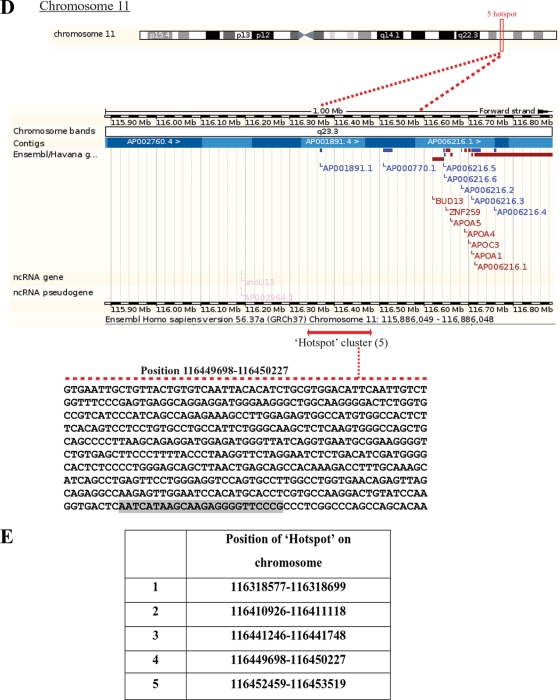

We next asked if CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization may be a frequent occurrence across the genome by taking advantage of existing databases recording CTCF and PARP-1 distribution patterns in the human genome (13, 59). The sites of overlap (hot spots) for CTCF and PARP-1 are summarized in relation to specific chromosomes in Fig. 6A, and the corresponding chromosome positions are shown in Fig. 6B. In order to confirm that CTCF and PARP-1 occupied the identified sites of overlap, we randomly chose three hot spots on chromosomes 7, 11, and 21. Using the ChIP samples obtained from the B4 cell experiments (Fig. 5D), we observed enrichment for both CTCF and PARP-1 at all three sites tested, although to different extents (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Colocalization of CTCF and PARP-1 across the genome. (A) Summary of the microarray data obtained from two independent ChIP-ChIP experiments studying CTCF and PARP-1, deposited in the GEO database. Numerous colocalization sites within human DNA were identified. The table indicates the number of identified CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization hot spots with regard to the specific human chromosomes. (B) Correlated sites (hot spot clusters) of CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization mapped to human chromosomes. The numbers of hot spots on the chromosomes are shown. (C) Validation of the identified CTCF and PARP-1 colocalization sites using three randomly chosen sites positioned on chromosomes 7, 11, and 21. Real-time PCR was performed using a selection of the ChIP samples obtained in the B4 cell experiments (Fig. 5D). The single ChIP samples were analyzed with anti-His tag, anti-PARP-1, and antitubulin antibodies, and re-ChIP samples were analyzed with anti-His tag/anti-PARP-1, anti-PARP-1/anti-His tag, and antitubulin/anti-PARP-1 antibodies. The efficiency of ChIP was calculated as a percentage of the starting material (percent input). At all three chromosomal sites, enrichment is observed, indicating colocalization of CTCF and PARP-1 at these chromosomal positions. (D) Chromosome 11 is shown as an example of a “chromosome region in detail.” The Ensembl genome browser was used to map the sites of CTCF/PARP-1 colocalization. (Top) The chromosomal position of the hot spot cluster comprising five hot spots is shown. (Middle) The region in detail shows genes within the area of CTCF/PARP-1 colocalization. (Bottom) One of the identified colocalization hot spots, hot spot 4, is expanded to reveal the DNA sequence, and a putative CTCF binding site is highlighted. ncRNA, noncoding RNA. (E) Chromosomal positions of the five identified hot spots in a cluster on chromosome 11.

Searches were then performed and positions of hot spot clusters were mapped with the Ensembl genome browser; these positions are shown as the relevant “chromosome region in detail” in Fig. 6D and Fig. S8A to N in the supplemental material. The sequence of hot spot 4 on chromosome 11, obtained from the CTCF motif reported previously (50), is presented in Fig. 6D (bottom) with a putative CTCF binding site highlighted. The genome locations for all five hot spots in a cluster on chromosome 11 are shown in Fig. 6E.

This analysis revealed that there is overlap in the localization patterns of CTCF and PARP-1 on many of the chromosomes, although no such overlap was found on chromosomes 1, 9, 13, 14, 15, 20, and X. The locations of the overlap sites were both intergenic and intragenic, as exemplified on chromosome 11 (Fig. 6D) and several other chromosomes (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). No information was available for CTCF localization on chromosomes 3, 17, and Y or for PARP-1 localization on chromosome Y.

The distribution of regions of CTCF/PARP-1 overlap varied among chromosomes, and interestingly, the sites of overlap appeared to be clustered on the chromosomes, suggesting that these features may be linked to specific functions of CTCF and PARP-1 at these sites.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we further characterized two forms of CTCF, CTCF-130 and CTCF-180, with regard to their PARylation status. CTCF-130 was previously suggested to be the non-PARylated form of CTCF (92) whose predominance in all cellular contexts has been well established (26, 33, 54, 55, 72, 77, 83). Further detailed analysis of CTCF-130 and CTCF-180 revealed the complex nature of CTCF PARylation. Both forms appear to be PARylated, although to different extents (Fig. 1B and C): CTCF-180 is likely to be highly PARylated, whereas CTCF-130 may contain only a few ADP-ribose residues. Two lines of evidence support this proposition: (i) CTCF-130 can be detected only by the rabbit polyclonal antibody (Fig. 1B), and (ii) PARylated CTCF-130 comigrates with the non-PARylated form of CTCF (Fig. 1F). These data demonstrate that the CTCF-130 band seen upon SDS-PAGE represents different populations of CTCF, which may contain mono(ADP-ribose), oligo(ADP-ribose), and unmodified CTCF; similar observations have been made in a recent report (91). Our findings suggest that the two PARylated forms of CTCF, CTCF-130 and CTCF-180, may be involved in functional regulation in different cell contexts (see below).

Intriguingly, PARylation of CTCF-130 with PARP-1 (92) and enzymatic degradation of CTCF-180 with PARG (Fig. 1A) result in the appearance of discrete bands of CTCF-180 and CTCF-130, respectively. The absence of a discernible CTCF protein smear, indicating varying modification levels, suggested that a distinct mechanism may contribute to the dramatic increase/decrease in the molecular mass of CTCF following PARylation and de-PARylation. This phenomenon requires further investigation.

The coexistence of differentially ADP-ribosylated forms of CTCF supports the current view of the biochemistry of the PARylation reaction, which requires preformed mono(ADP-ribosyl)ated substrates. Several enzymes, such as mono(ADP-ribosyl)transferase, PARP-1 itself, other PARP family members, and heteromers of these proteins, may mono(ADP-ribosyl)ate CTCF, which can then be used for the PARylation reaction (43, 73).

Although CTCF-180 usually represents only a minor fraction of the total CTCF population, our recent study shows that CTCF-180 is the predominant isoform in many normal human tissues and the only isoform in normal breast tissues, with CTCF-130 associated with cell proliferation, whereas CTCF-180 is associated with nondividing cells (27). In this context, the low levels of endogenous CTCF-180 in the cell lines, as well as the absence/very low levels of CTCF-180 produced from the exogenous CTCF-expressing constructs (reference 40 and this study), may be explained by rapid degradation of PAR, typical for proliferating cells in culture, where the half-life of PAR is less than a minute (5, 90).

To specifically examine the role of PARylation in CTCF functions, we generated a CTCF mutant deficient in PARylation by mutating the cluster of glutamic acid residues, the preferred acceptors of PARylation, in the N-terminal domain of CTCF (Fig. 1E). To our knowledge, this is the first example of the generation of a mutant protein completely deficient in PARylation in vivo; a recently described PARylation-deficient p53 mutant still demonstrated residual in vivo PARylation (45). The non-PARylated CTCF Mut4 was identical to the CTCF WT by the following criteria: (i) protein size of 130 kDa upon SDS-PAGE, protein stability, and similar protein levels produced from the plasmid vectors (Fig. 1F, 2B, and 4C and data not shown), (ii) localization and distribution patterns in the nucleus (Fig. 3B), and (iii) ability to bind to DNA (Fig. 4E and 5D). These findings are in contrast with the reports that PARylation alters the stability and DNA binding activity of proteins (81, 89).

In the present study, in all experimental systems tested, the differences in CTCF PARylation resulted in the loss of CTCF function. In the presence of PJ34, a potent PARP inhibitor, or transfection with the plasmid expressing CTCF Mut4, the activity of the p19ARF promoter-driven reporter was considerably reduced, suggesting that CTCF function as a transcriptional regulator is PARylation dependent. Notably, the effects of PARylation in cell lines of different origins seem to vary, thus indicating that cell context may play a “tuning” role in CTCF regulation.

The inhibitory role of CTCF in cell proliferation was also compromised by CTCF Mut4 (Fig. 3). It is conceivable that this regulation occurs through transcriptional regulation of CTCF target genes controlling proliferation, such as p19ARF (32, 33, 62), c-myc (62), pRb (24), BRCA1 (17), and possibly p21 and p27 (76). Recent studies also implicated CTCF in the regulation of ribosomal biogenesis (84) and replication timing (12). Thus, since CTCF effects on cell proliferation are likely to involve various regulatory pathways, alterations in CTCF PARylation may lead to global changes in cell biology.

In our previous investigations, we used similar assays to assess the effects of CTCF phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2 on CTCF functions, which generally resemble those of CTCF PARylation (29, 53). Cross talk between the two pathways may occur and may explain the similar functional outcomes; these observations require further examination. Functional regulation by both modifications, PARylation and phosphorylation, is not unusual and has been reported previously for p53 and histones (30, 41, 70).

Finally, the insulator function of CTCF, tested using a stable isogenic insulator reporter cell system and a mouse-human hybrid cell line, was also perturbed by PJ34 and CTCF Mut4 (Fig. 4). Using this system, we explored a hypothesis that CTCF functional activities regulated by PARylation are facilitated mechanistically by the close proximity of CTCF and PARP (Fig. 5E). In this model, PARylation of CTCF is established by PARPs present at the same DNA site and can be reversed by PARG. We were not able to establish the presence of PARG at the insulator or association with PARP-1 and CTCF due to the absence of ChIP-grade anti-PARG antibodies; however, interaction between PARP-1 and PARG has been reported in the literature (36, 48).

In the proposed model, a feedback axis can be envisaged whereby CTCF can directly regulate PARP-1, which in turn may lead to DNA hypomethylation (40). Cooperation between CTCF and PARP-1 may provide a link between PARylation and DNA methylation, thereby adding another layer of complexity to the model. These aspects deserve further investigation.

The notions that CTCF is stably bound to its DNA targets and that regulatory signals are responsible for the modulation of CTCF activity are supported by previously published observations (63, 92). However, such close association between CTCF and PARP-1 may not be required for CTCF regulation by PARylation at all CTCF targets (91).

The genome-scale association between CTCF and the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation mark was shown previously with the mouse microarray library of CTCF binding sites (71, 92). In the present investigation, considerable overlap between CTCF and PARP-1 in the nuclei in different cell lines was confirmed (Fig. 5B and C; see also Fig. S7B in the supplemental material). Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis of the distributions of CTCF (13) and PARP-1 (59) in the ENCODE regions of the genome in human cell lines revealed sizable areas of overlap between CTCF and PARP-1 on different chromosomes (Fig. 6D and E; see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), with three of the identified CTCF/PARP-1 colocalizaton sites validated (Fig. 6C). Although the ChIP-ChIP data for CTCF and PARP-1 were obtained from different cells lines, previous reports indicate that CTCF occupancy at its binding sites is conserved among different cell lines (9, 13, 50).

In this context, it is important to acknowledge the substantial overlap between CTCF and cohesin binding sites throughout the genome, which is believed to have important functional implication in the regulation of gene expression and is the subject of much current research (references 38, 39, and 74 and references therein). The results of our study, indicating the frequency of colocalization of CTCF and PARP-1, lead us to hypothesize that CTCF, PARP-1, and cohesin may all appear in one complex. This hypothesis deserves further investigation.

A common theme of this study is that CTCF and PARP-1 are important elements of the same regulatory pathway(s) and likely to be linked by a feedback mechanism. Therefore, PARP-1 dysfunction may lead to loss of CTCF PARylation and, as a result, dramatic changes in gene regulation and development of disease, in particular cancer. Alternatively, deregulation of PARP-1 by aberrant CTCF protein may also contribute to tumorigenesis. In this context, it is significant that both CTCF and PARP-1 display features of tumor suppressors (2, 31, 54, 68, 78). However, the interrelationship between CTCF and the PARylation enzymatic machinery appears to be more complex, as CTCF and PARylation enzymes are likely to be shared by different functional complexes. Such sharing may be important for functional integration of different cellular processes in response to various stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Docquier, A. Harrison, R. Meyer, M. Meyer-Ficca, and N. Curtin for helpful discussions. We are grateful to V. Lobanenkov for the gift of the anti-CTCF monoclonal antibody, L. Kraus for the gift of the anti-PARP-1 antibody, and M. Oshimura and A. Feinberg for A911M and A911P mouse-human hybrid cells.

Funding for this work was from the Medical Research Council (to D.F., S.R., and E.K.), the Breast Cancer Campaign (to S.R. and E.K.), the University of Essex (to E.K. and I.C.), the Swedish Science Research Council (to R.O.), the Swedish Cancer Research Foundation (to R.O.), the Swedish Pediatric Cancer Foundation (to R.O.), the Lundberg Foundation (to R.O.), HEROIC and ChILL (European Union integrated projects; to R.O.), a Cancer Research United Kingdom senior cancer research fellowship (to A.M.), the Wenner-Gren Foundation (to M.J.), and an Association of International Cancer Research grant (to A.M. and Y.I.). We acknowledge the support of the University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK, and Hutchison Whampoa Limited (to A.M., M.J., and Y.I.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Affar, E. B., P. J. Duriez, R. G. Shah, E. Winstall, M. Germain, C. Boucher, S. Bourassa, J. B. Kirkland, and G. G. Poirier. 1999. Immunological determination and size characterization of poly(ADP-ribose) synthesized in vitro and in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1428:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar-Quesada, R., J. A. Munoz-Gamez, D. Martin-Oliva, A. Peralta-Leal, R. Quiles-Perez, J. M. Rodriguez-Vargas, M. R. de Almodovar, C. Conde, A. Ruiz-Extremera, and F. J. Oliver. 2007. Modulation of transcription by PARP-1: consequences in carcinogenesis and inflammation. Curr. Med. Chem. 14:1179-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Althaus, F. R., and C. Richter. 1987. ADP-ribosylation of proteins. Enzymology and biological significance. Mol. Biol. Biochem. Biophys. 37:1-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altmeyer, M., S. Messner, P. O. Hassa, M. Fey, and M. O. Hottiger. 2009. Molecular mechanism of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1 and identification of lysine residues as ADP-ribose acceptor sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3723-3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Gonzalez, R., and F. R. Althaus. 1989. Poly(ADP-ribose) catabolism in mammalian cells exposed to DNA-damaging agents. Mutat. Res. 218:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ame, J. C., C. Spenlehauer, and G. de Murcia. 2004. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays 26:882-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awad, T. A., J. Bigler, J. E. Ulmer, Y. J. Hu, J. M. Moore, M. Lutz, P. E. Neiman, S. J. Collins, R. Renkawitz, V. V. Lobanenkov, and G. N. Filippova. 1999. Negative transcriptional regulation mediated by thyroid hormone response element 144 requires binding of the multivalent factor CTCF to a novel target DNA sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27092-27098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakondi, E., P. Bai, E. E. Szabo, J. Hunyadi, P. Gergely, C. Szabo, and L. Virag. 2002. Detection of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in oxidatively stressed cells and tissues using biotinylated NAD substrate. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barski, A., S. Cuddapah, K. Cui, T. Y. Roh, D. E. Schones, Z. Wang, G. Wei, I. Chepelev, and K. Zhao. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell, A. C., and G. Felsenfeld. 2000. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 405:482-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell, A. C., A. G. West, and G. Felsenfeld. 1999. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell 98:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergstrom, R., J. Whitehead, S. Kurukuti, and R. Ohlsson. 2007. CTCF regulates asynchronous replication of the imprinted H19/Igf2 domain. Cell Cycle 6:450-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birney, E., J. A. Stamatoyannopoulos, A. Dutta, R. Guigo, T. R. Gingeras, E. H. Margulies, Z. Weng, M. Snyder, E. T. Dermitzakis, R. E. Thurman, M. S. Kuehn, C. M. Taylor, S. Neph, C. M. Koch, S. Asthana, A. Malhotra, I. Adzhubei, J. A. Greenbaum, R. M. Andrews, P. Flicek, P. J. Boyle, H. Cao, N. P. Carter, G. K. Clelland, S. Davis, N. Day, P. Dhami, S. C. Dillon, M. O. Dorschner, H. Fiegler, P. G. Giresi, J. Goldy, M. Hawrylycz, A. Haydock, R. Humbert, K. D. James, B. E. Johnson, E. M. Johnson, T. T. Frum, E. R. Rosenzweig, N. Karnani, K. Lee, G. C. Lefebvre, P. A. Navas, F. Neri, S. C. Parker, P. J. Sabo, R. Sandstrom, A. Shafer, D. Vetrie, M. Weaver, S. Wilcox, M. Yu, F. S. Collins, J. Dekker, J. D. Lieb, T. D. Tullius, G. E. Crawford, S. Sunyaev, W. S. Noble, I. Dunham, F. Denoeud, A. Reymond, P. Kapranov, J. Rozowsky, D. Zheng, R. Castelo, A. Frankish, J. Harrow, S. Ghosh, A. Sandelin, I. L. Hofacker, R. Baertsch, D. Keefe, S. Dike, J. Cheng, H. A. Hirsch, E. A. Sekinger, J. Lagarde, J. F. Abril, A. Shahab, C. Flamm, C. Fried, J. Hackermuller, J. Hertel, M. Lindemeyer, K. Missal, A. Tanzer, S. Washietl, J. Korbel, O. Emanuelsson, J. S. Pedersen, N. Holroyd, R. Taylor, D. Swarbreck, N. Matthews, M. C. Dickson, D. J. Thomas, M. T. Weirauch, J. Gilbert, et al. 2007. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447:799-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonicalzi, M. E., J. F. Haince, A. Droit, and G. G. Poirier. 2005. Regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase: where and when? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:739-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun, S. A., P. L. Panzeter, M. A. Collinge, and F. R. Althaus. 1994. Endoglycosidic cleavage of branched polymers by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Eur. J. Biochem. 220:369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burcin, M., R. Arnold, M. Lutz, B. Kaiser, D. Runge, F. Lottspeich, G. N. Filippova, V. V. Lobanenkov, and R. Renkawitz. 1997. Negative protein 1, which is required for function of the chicken lysozyme gene silencer in conjunction with hormone receptors, is identical to the multivalent zinc finger repressor CTCF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1281-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butcher, D. T., and D. I. Rodenhiser. 2007. Epigenetic inactivation of BRCA1 is associated with aberrant expression of CTCF and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT3B) in some sporadic breast tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 43:210-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caiafa, P., and J. Zlatanova. 2009. CCCTC-binding factor meets poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J. Cell. Physiol. 219:265-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chernukhin, I., S. Shamsuddin, S. Y. Kang, R. Bergstrom, Y. W. Kwon, W. Yu, J. Whitehead, R. Mukhopadhyay, F. Docquier, D. Farrar, I. Morrison, M. Vigneron, S. Y. Wu, C. M. Chiang, D. Loukinov, V. Lobanenkov, R. Ohlsson, and E. Klenova. 2007. CTCF interacts with and recruits the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II to CTCF target sites genome-wide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:1631-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernukhin, I. V., S. Shamsuddin, A. F. Robinson, A. F. Carne, A. Paul, A. I. El-Kady, V. V. Lobanenkov, and E. M. Klenova. 2000. Physical and functional interaction between two pluripotent proteins, the Y-box DNA/RNA-binding factor, YB-1, and the multivalent zinc finger factor, CTCF. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29915-29921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiarugi, A. 2002. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: killer or conspirator? The ‘suicide hypothesis’ revisited. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuddapah, S., R. Jothi, D. E. Schones, T. Y. Roh, K. Cui, and K. Zhao. 2009. Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 19:24-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Amours, D., S. Desnoyers, I. D'Silva, and G. G. Poirier. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 342(Pt. 2):249-268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De La Rosa-Velazquez, I. A., H. Rincon-Arano, L. Benitez-Bribiesca, and F. Recillas-Targa. 2007. Epigenetic regulation of the human retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene promoter by CTCF. Cancer Res. 67:2577-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Murcia, G., and S. Shall. 2000. From DNA damage and stress signalling to cell death: poly ADP-ribosylation reactions. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 26.Docquier, F., D. Farrar, V. D'Arcy, I. Chernukhin, A. F. Robinson, D. Loukinov, S. Vatolin, S. Pack, A. Mackay, R. A. Harris, H. Dorricott, M. J. O'Hare, V. Lobanenkov, and E. Klenova. 2005. Heightened expression of CTCF in breast cancer cells is associated with resistance to apoptosis. Cancer Res. 65:5112-5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Docquier, F., G. X. Kita, D. Farrar, P. Jat, M. O'Hare, I. Chernukhin, S. Gretton, A. Mandal, L. Alldridge, and E. Klenova. 2009. Decreased poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of CTCF, a transcription factor, is associated with breast cancer phenotype and cell proliferation. Clin. Cancer Res. 15:5762-5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn, K. L., and J. R. Davie. 2003. The many roles of the transcriptional regulator CTCF. Biochem. Cell Biol. 81:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Kady, A., and E. Klenova. 2005. Regulation of the transcription factor, CTCF, by phosphorylation with protein kinase CK2. FEBS Lett. 579:1424-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faraone-Mennella, M. R. 2005. Chromatin architecture and functions: the role(s) of poly(ADP-RIBOSE) polymerase and poly(ADPribosyl)ation of nuclear proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83:396-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filippova, G. N. 2008. Genetics and epigenetics of the multifunctional protein CTCF. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 80:337-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]