Abstract

Claviceps purpurea, the fungal pathogen that causes the cereal disease ergot, produces glycerides that contain high levels of ricinoleic acid [(R)-12-hydroxyoctadec-cis-9-enoic acid] in its sclerotia. Recently, a fatty acid hydroxylase (C. purpurea FAH [CpFAH]) involved in the biosynthesis of ricinoleic acid was identified from this fungus (D. Meesapyodsuk and X. Qiu, Plant Physiol. 147:1325-1333, 2008). Here, we describe the cloning and biochemical characterization of a C. purpurea type II diacylglycerol acyltransferase (CpDGAT2) involved in the assembly of ricinoleic acid into triglycerides. The CpDGAT2 gene was cloned by degenerate RT-PCR (reverse transcription-PCR). The expression of this gene restored the in vivo synthesis of triacylglycerol (TAG) in the quadruple mutant strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae H1246, in which all four TAG biosynthesis genes (DGA1, LRO1, ARE1, and ARE2) are disrupted. In vitro enzymatic assays using microsomal preparations from the transformed yeast strain indicated that CpDGAT2 prefers ricinoleic acid as an acyl donor over linoleic acid, oleic acid, or linolenic acid, and it prefers 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol over 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol as an acyl acceptor. The coexpression of CpFAH with CpDGAT2 in yeast resulted in an increased accumulation of ricinoleic acid compared to the coexpression of CpFAH with the native yeast DGAT2 (S. cerevisiae DGA1 [ScDGA1]) or the expression of CpFAH alone. Northern blot analysis indicated that CpFAH is expressed solely in sclerotium cells, with no transcripts of this gene being detected in mycelium or conidial cells. CpDGAT2 was more widely expressed among the cell types examined, although expression was low in conidiospores. The high expression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in sclerotium cells, where high levels of ricinoleate glycerides accumulate, provided further evidence supporting the roles of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH as key enzymes for the synthesis and assembly of ricinoleic acid in C. purpurea.

Diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) catalyzes the final and committed step in triacylglycerol (TAG) biosynthesis from the substrates diacylglycerol (DAG) and fatty acyl-coenzyme A (CoA). Although DGAT activity was reported first in chicken liver in 1956 (30), only in the last few years have DGAT genes been cloned and characterized at the molecular level. Cases et al. (7) cloned the first DGAT gene from the mouse by using homology searches of expressed sequence tag (EST) databases with a mammalian acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) as the query sequence. The DGAT identified shared 20% identity at the amino acid level with the ACAT translation product. The mouse DGAT later was named DGAT1, so as to distinguish it from subsequently identified types of DGATs. An in vitro assay of mouse DGAT1 showed that, in addition to DGAT activity, this enzyme also could catalyze the esterification of a fatty acyl-CoA with monoacylglycerol, generating diacylglycerols (31). Mice lacking DGAT1 have reduced levels of wax esters in their fur (8), and the overexpression of DGAT1 in cells led to a 10-fold increase in wax synthase activity (31).

The existence of the second type of DGAT (DGAT2) was suggested initially by the observation that an Arabidopsis mutant, with the single-copy Arabidopsis thaliana DGAT1 (AtDGAT1) gene disrupted, still accumulated substantial amounts of TAGs (24). Furthermore, Smith et al. (27) reported that mice lacking DGAT1 retained a large amount of TAGs in their tissues. Lardizabal et al. (18) were the first to actually clone a DGAT2 gene through the use of purified enzyme from the fungus Mortierella ramanniana. Since then, DGAT2 genes have been identified from various organisms, including fungi, plants, and animals (32).

Although DGAT1 and DGAT2 catalyze the same reaction, they share no or little similarity in amino acid sequence. Furthermore, compared to DGAT1, DGAT2 appears to be more active in lower concentrations of acyl-CoA (≤50 μM) and less active when less than 50 mM magnesium is used (6). The two enzymes also may differ in terms of substrate specificities. Substrate specificity assays using a mammalian DGAT2 expressed in insect cells showed that oleoyl-CoA was utilized preferentially, followed by palmitoyl-CoA, while activity levels with linoleoyl- and arachidonyl-CoA were similar (6). However, in enzymatic assays using solubilized and nonsolubilized samples of the fungal DGAT2 from M. ramanniana, no significant preference between 12:0-CoA and 18:1-CoA as an acyl donor substrate was detected (18).

Few data are available regarding the ability of DGAT2 to use unusual fatty acids as substrates. This may be due to the fact that DGAT2 exhibits lower activity in in vitro assays than DGAT1, suggesting that the optimization of assay conditions is required. In addition, the chemically labile properties of unusual fatty acids often make in vitro assays difficult to monitor (26). Despite these difficulties, Shockey et al. (26) demonstrated a 5-fold increase in the accumulation of α-eleastearic acid-containing TAGs in yeast expressing the tung tree DGAT2 compared to that of the sample expressing DGAT1. An in vitro assay of castor DGAT2 (Ricinus communis DGAT2 [RcDGAT2]) using sn-1,2-diricinolein as an acyl acceptor and [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA as an acyl donor (5, 17) indicated that the enzyme preferentially utilized DAGs containing ricinoleic acid as the acyl acceptor. Furthermore, the expression of RcDGAT2 along with the castor hydroxylase RcFAH in Arabidopsis led to an increased accumulation of ricinoleic acid (5). However, so far no DGAT2 has been functionally proven to preferentially utilize an unusual fatty acid as an acyl donor in TAG synthesis.

Claviceps purpurea is the causal agent of the disease ergot in cereal crops such as wheat, barley, and oat. It infects young flowers by mimicking pollen grains to penetrate style tissues. After reaching the ovary of the inflorescence, it forms a specialized structure called a sclerotium, in which high levels of ricinoleic acid accumulate, in some cases amounting to as much as 50% of the total fatty acids in sclerotium oil (2). Ricinoleic acid, a hydroxyl fatty acid [(R)-12-hydroxyoctadec-cis-9-enoic acid] with many specialized uses in the chemical industry, has been the subject of a great deal of scientific interest in recent years. An oleate 12-hydroxylase, C. purpurea FAH (CpFAH), recently identified from this fungus catalyzes the hydroxylation of oleic acid at the 12 position (20) to produce ricinoleic acid. In this report, we describe the molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of a C. purpurea cDNA encoding a type II acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (CpDGAT2) that preferentially uses ricinoleic acid as a substrate for TAG synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The quadruple mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain H1246 (MATα are1-Δ::HIS3 are2-Δ::LEU2 dga1-Δ::KanMX4 lro1-Δ::TRP1 ADE2) (25) and the wild-type S. cerevisiae strain INVSc1 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2 trp1-289 ura3-52; Invitrogen) were used as heterologous hosts to study the expression of CpDGAT2. Transformed yeast cells were cultivated at 28°C on minimal medium (synthetic dropout medium) lacking uracil and including 2% glucose or galactose. For the production of sclerotium-like cells and conidia, Claviceps purpurea was grown at 25°C in the dark in an amino-nitrogen medium (ANM) containing sucrose (100 g/liter), l-asparagine (5 g/liter), or other l-amino acids in amounts supplying equivalent nitrogen, e.g., 10 g/liter aspartic acid, 0.25 g/liter KH2PO4, 0.25 g/liter MgSO4·7H2O, 0.125 g/liter KCl, 0.033 g/liter FeSO4·7H2O, and 0.027 g/liter ZnSO4·7H2O (19). Potato dextrose agar (PDA) was used to maintain C. purpurea in the mycelium stage.

Cloning of the CpDGAT2 cDNA from C. purpurea.

Total RNA was extracted from sclerotium-like tissues of C. purpurea using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 5 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Two microliters of the first-strand cDNA was used as a template for PCR amplification with degenerate oligonucleotide primers (DM51, TAYATHTTYGGITAYCAYCCICAYGG, and DM53, TGITCRTAIARRTCIKTYTCICCRAA) that were designed based on conserved amino acid regions of DGAT2 enzymes from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the fungus Mortierella ramanniana, and the mammal Mus musculus. The forward primer DM51 and the reverse primer DM53 correspond to the amino acid sequences YIFGYHPHG and FGE(N/T)DLY(D/E)Q, respectively. Amplified products with the expected size of approximately 400 bp were gel purified, cloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and sequenced. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the CpDGAT2 cDNA were obtained using a Marathon cDNA amplification kit (BD Biosciences, Clontech) by following the manufacturer's recommendations. Primers DM66 (5′-CCCGCGCGCAGAGCCACCTTGATG-3′) and DM65 (5′-CGGTGCGCCTTCGCCACCAATGC-3′) were used to obtain the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The full-length sequence, including the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions as well as the coding region, was amplified using Pfx50 DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with the specific primers DM83 (5′-CGGCGCGGCCTCGTTGAGCTCC-3′) and DM84 (5[prime]-CCCCCAACTTCCCCCTGCGAAAGC-3′).

Heterologous expression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in yeast.

For the functional expression of CpDGAT2 in yeast, the gene was amplified by PCR using the primers DM85 (5′-CAGGATCCGAGATGGCAGCCGTCCAAGTC-3′) and DM82 (5′-ACGCTAGCTCAAGACAAGATCTGCAGCTC-3′), and the amplification product was cloned into the yeast expression vector pYES2.1. For coexpression experiments, the CpFAH gene flanked with EcoRI sites first was inserted in the yeast pESC-URA vector (Stratagene) behind the GAL10 promoter and the native Saccharomyces cerevisiae DGAT2 gene (ScDga1), or CpDGAT2 then was cloned in the BamHI/NheI sites of the vector behind the GAL1 promoter. Recombinant plasmids were transferred into the yeast S. cerevisiae H1246 strain using the method described by Gietz and Woods (14).

In vitro enzymatic assays.

Transformed yeast cells were cultivated in synthetic minimal dropout medium lacking uracil and containing 2% (wt/vol) galactose, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 400 mM sucrose, 100 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). After the addition of acid-washed glass beads, the cells were disrupted using a tabletop bead beater (three cycles of 1 min each). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant fraction was removed and centrifuged at 10,0000 × g for 1 h. The resulting microsomal membrane fraction was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20% glycerol, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use. The protein concentration in the microsomal sample was determined by the Bradford dye-binding assay (3). DGAT activity was measured as the production of [14C]triacylglycerol from [1-14C]acyl-CoAs and unlabeled DAGs. For the acyl donor specificity assay, the reaction mixture (0.1 ml) consisted of 20 μg microsomal protein, 16.2 μM (55 mCi/mmol) [1-14C]acyl-CoA ([1-14C]oleoyl-CoA, [1-14C]linoleoyl-CoA, [1-14C]linolenoyl-CoA, or [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA), and 400 μM 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol in a buffer of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (15). The assay mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 min, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 ml of isopropanol-CH2Cl2 (2:1, vol/vol). After the reaction was stopped, radiolabeled glycerolipids were isolated by adding 1 ml 0.9% NaCl and 2 ml of CH2Cl2. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged, and the lower organic phase was transferred to a new glass tube and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen gas. The radiolabeled glycerolipids were resuspended in chloroform and subjected to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) separation on silica gel-G plates. The experimental conditions for the acyl acceptor assay were the same as those described above, except that [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA was incubated with different acyl acceptors.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNAs from different stages of C. purpurea grown in ANM or PDA medium were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of RNA samples was determined spectrophotometrically and by comparison to a marker standard after gel electrophoresis. For each sample, 7 μg of total RNA was fractionated on a denaturing agarose gel and transferred onto a nylon membrane according to Ausubel et al. (1). CpDGAT2 and CpFAH probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using the Random Primers DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen). Prehybridization, hybridization, and washing procedures were performed according to Davis et al. (10). Radioactivity was detected by exposure on Kodak Biomax MR film (20.3 by 25.4 cm), and film was developed using developing solutions (White Mountain Imaging, Salisbury, NH) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Lipid analysis.

Total lipids from C. purpurea or transformed yeast cells were extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol) according to Pillai et al. (22). The lipid sample was fractionated on silica gel-G plates using a mobile phase of organic solvent as described by Donaldson (11). For the visualization of separated lipids, the developed TLC plates were air dried, sprayed with primulin staining solution (5 mg of primulin dissolved in 100 ml acetone-water; 80:20, vol/vol) and observed under a UV light. The monoricinolein standard was purified from Ricinus communis oil according to Donaldson (11). TLC plates loaded with lipids from the CpDGAT2 assay containing nonhydroxylated acyl donors were developed in hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (70:30:1, vol/vol/vol), while TLC plates loaded with lipids from the CpDGAT2 assay containing [1-14]ricinoleoyl-CoA acyl-donors were developed in hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (70:140:3 vol/vol/vol). The level of radioactivity incorporated into lipid classes was determined by scanning developed plates with a radioimage analyzer (Bioscan GC-252). Radiolabeled bands then were scraped from the plate, and the radioactivity of the lipid classes was determined using a Beckman liquid scintillation system (22).

The fatty acid analysis of the total cellular lipids and of lipid classes was performed essentially according to Reed et al. (23). Yeast pellets were saponified with 2 ml of 10% (wt/vol) methanolic KOH in a sealed culture tube at 80°C for 2 h. Samples were cooled, and the nonsaponifiable lipids were preextracted twice with 2 ml of hexane. The methanol phase was neutralized with 2 ml of 50% HCl, and free fatty acids were extracted twice with 2 ml of hexane and transmethylated with 3 N methanolic-HCl at 80°C for 2 h. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) then were dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in 200 μl of hexane. For the identification of hydroxyl fatty acids, 100 μl of resuspended FAMEs was treated with 20 μl of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide-pyridine (1:1, vol/vol). FAME samples were analyzed in a Hewlett-Packard 5890A gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a DB-23 column (30 m by 0.25 mm) with a 0.25-μm film thickness and a flame ionization detector (FID). The column temperature was maintained at 160°C for 1 min and then was raised to 240°C at a rate of 4°C/min (21).

RESULTS

Cloning of a diacylglycerol acyltransferase from C. purpurea.

To clone the C. purpurea gene encoding the type II diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) involved in the formation of ricinoleic acid-containing triacylglycerols, a pair of degenerate oligonucleotide primers was designed based on conserved regions of fungal and mammalian DGAT2 sequences. RT-PCR amplification with the degenerate primers using the total RNA extracted from sclerotium-like tissues as a template generated a DNA fragment of about 400 bp in length that showed sequence similarity to type II DGATs from other species. The rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method then was used to obtain a full-length cDNA, which was designated CpDGAT2. The open reading frame of CpDGAT2 was 1,314 nucleotides in length, and it encoded a 437-amino-acid polypeptide with a predicted molecular mass of 48.9 kDa. A comparison of the CpDGAT2 protein to related sequences indicated it had 41.6, 25, and 38.2% amino acid identity to Mortierella ramanniana (DGAT2; GenBank accession number AF391089), castor bean (RcDGAT2; GenBank accession number AAY16324), and human (HsDGAT2; GenBank accession number AAQ88896) DGAT2 sequences, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that CpDGAT2 is tightly clustered with the fungal Mortierella ramanniana DGAT2 (MrDGAT2), which forms a group with the yeast DGAT2 (ScDGAT2). This group is distantly separated from two other groups of DGAT2s from plants and animals (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenic analysis of CpDGAT2 and related proteins. The unrooted tree was constructed using the Geneious 4.6.4 software program. The proteins shown are MrDGAT2 (Mortierela ramanniana; AF391090), ScDGAT2 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; YOR245C), VfDGAT2 (Vernicia fordii; ABC94474), RcDGAT2 (Ricinus communis; AAY16324), AtDGAT2 (Arabidopsis thaliana; NP_566952), MmDGAT2 (Mus musculus; BAB22105), HsDGAT2 (Homo sapiens; AAQ88896), and CcDGAT2 (Caenorhabditis elegans; CAB04533).

Functional expression of CpDGAT2 in yeast.

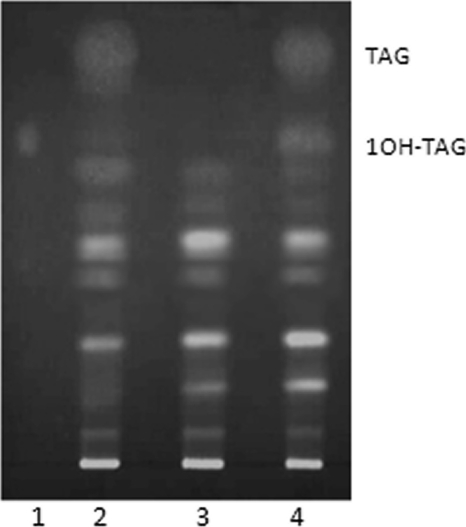

The putative CpDGAT2 identified from C. purpurea was expressed in the non-TAG-forming quadruple mutant S. cerevisiae strain H1246, in which all four of the genes (DGA1, LRO1, ARE1, and ARE2) involved in TAG biosynthesis are disrupted (25). The thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of neutral lipids extracted from transformed yeast cells grown in the presence of ricinoleic acid allowed the identification of several lipid classes including TAG fractions. DGAT activity was detected by the appearance of two TAG bands. One migrated to the same area as TAGs lacking hydroxyl fatty acids, while a second class of TAGs containing one hydroxyl fatty acid (monoricinolein) migrated to a slightly different position. These bands were detected in both mutant cells expressing CpDGAT2 and in wild-type cells harboring an empty vector, while TAGs were not detected in the non-TAG-forming mutant strain harboring an empty vector (S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/blank) (Fig. 2). The monoricinolein band from the mutant cells expressing CpDGAT2 contained 33.7% ricinoleic acid, indicating that CpDGAT2 can utilize ricinoleic acid in the synthesis of hydroxyl fatty acid-containing TAGs.

FIG. 2.

Thin-layer chromatography of lipids extracted from yeast transformants. Cells were cultivated in 10 ml of minimal medium lacking uracil, supplemented with 2% galactose for 24 h at 28°C in the presence of ricinoleic acid. Total lipids were extracted from 1.5 g of cells. Column 1, standard consisting of triacylglycerol with one ricinoleic acid; column 2, S. cerevisiae INVSC1 (pYES2.1/blank); column 3, S. cerevisiae H1246 (pYES2.1/blank); column 4, S. cerevisiae H1246 (pYES2.1/CpDGAT2). Abbreviations: 1OH-TAG, monoricinolein; TAG, triacylglycerol.

Substrate specificity of CpDGAT2.

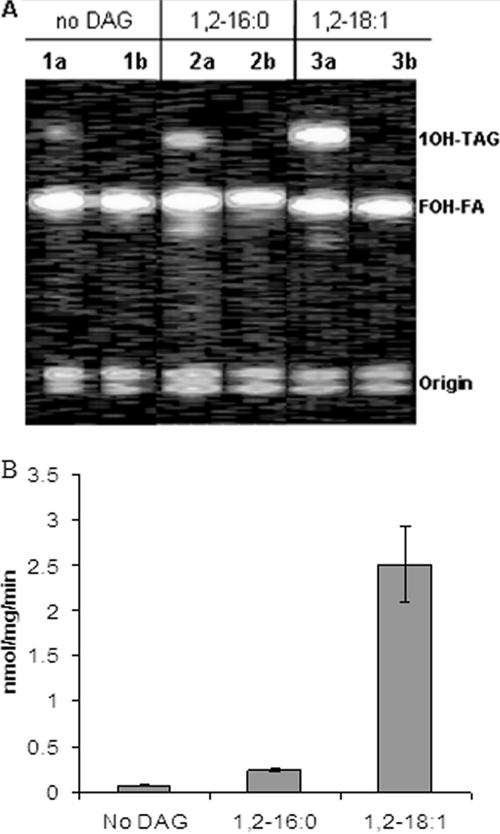

Acyl-CoA-diacylglycerol acyltransferase catalyzes the final acylation step in TAG biosynthesis by using acyl-CoA as an acyl donor and 1,2-sn-diacylglycerol as an acyl acceptor. To examine the acyl donor specificity of CpDGAT2, microsomal preparations from the mutant yeast strain H1246 expressing CpDGAT2 were incubated with different [1-14C]acyl-CoAs and unlabeled dioleoyl-DAG. Neutral lipids were extracted from the reactions and separated by TLC (Fig. 3). The analysis of [1-14C]acyl-containing lipids indicated that radioisotope-labeled TAGs were present in yeast cells expressing CpDGAT2 but not in control cells carrying an empty vector (Fig. 3A and B). The quantitative measurement of radioactivity in the TAG fractions of different acyl donor reactions showed that the largest amount of radioactivity was detected in the TAG fraction when ricinoleic acid was used as the acyl donor, followed by linoleic and oleic acids, with the smallest amount of radioactivity found when α-linolenic acid was used as an acyl donor (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Acyl donor specificity of CpDGAT2 as indicated by in vitro enzymatic assays. (A) TLC analysis of [1-14C]acyl-containing lipids after incubation of 1,2-diolein and various [1-14C]acyl-CoAs other than [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA with S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/CpDGAT2 microsomal preparations. Lipids were separated in hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (70:30:1, vol/vol/vol). (B) TLC analysis of [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-containing lipids after incubation of [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA and 1,2-diolein with S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/CpDGAT2 microsomal preparations. Ricinoleic acid-containing lipids were separated in hexane:diethyl ether:acetic acid (70:140:3, vol/vol/vol). Lanes 1a to d, S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/CpDGAT2; lanes 2a to d, S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/blank. TAG, triacylglycerol; FFA, free fatty acids; 1OH-TAG, triacylglycerol with one ricinoleic acid; FOH-FA, free ricinoleic acid. (C) Quantitative analysis of radioactivity found in TAGs after the incubation of various [1-14C]acyl-CoAs and 1,2-diolein with S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/CpDGAT2 microsomal preparations. The experiment was performed three times, and the bar represents the standard errors.

To examine the acyl acceptor specificity of CpDGAT2, microsomal preparations from yeast expressing CpDGAT2 were incubated with [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA and two commercially available DAG molecules (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol) (Fig. 4). The quantification of radioactivity present in the TAG fractions of the two acyl acceptor reactions indicated a much higher (more than 6-fold) accumulation of radioactive TAGs when 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol was used as an acyl acceptor, while the amount of radioactivity present in TAGs derived from 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol was approximately equal to the amount found in the control (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Acyl acceptor specificity of CpDGAT2 as indicated by in vitro enzymatic assays. (A) TLC separation of [14C]ricinoleoyl-containing lipids. 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycerol and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol were incubated with [14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA and 20 μg of microsomal protein. Lipids were separated in hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (70:140:3, vol/vol/vol). Lanes 1a to 3a, S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/CpDGAT2; lanes 1b to 3b, S. cerevisiae H1246-pYES2.1/blank. 1OH-TAG, TAGs with one ricinoleic acid; FOH-FA, free ricinoleic acid. (B) Quantitative analysis of radioactivity found in TAGs after incubation of yeast microsomal preparations of pYES2.1/CpDGAT2 with [1-14C]ricinoleoyl-CoA plus either 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol or 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol. The experiment was performed three times, and the bar represents standard deviations.

Coexpression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in yeast.

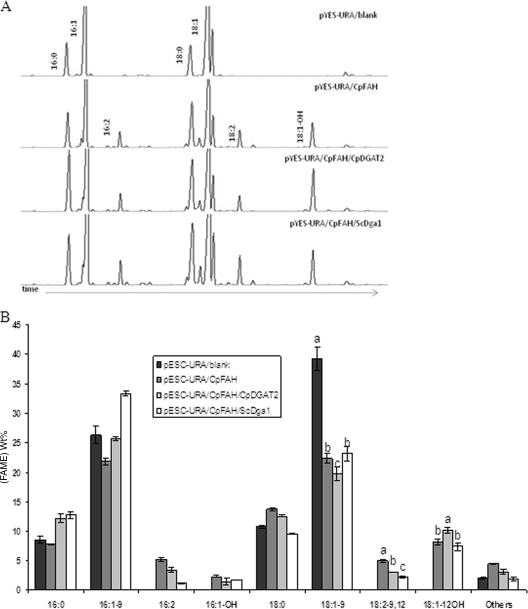

C. purpurea is known to produce high levels of ricinoleic acid in its sclerotium tissues, and a fatty acid hydroxylase (CpFAH) involved in the biosynthesis of this fatty acid was identified recently (20). To examine the influence of CpDGAT2 activity on the production of ricinoleic acid, we compared the effect of coexpressing this gene to the effect of coexpressing the native yeast DGAT2 (ScDga1) with CpFAH in a mutant yeast strain. As shown in Fig. 5, all constructs containing CpFAH produced significant quantities of three new fatty acids, namely, 16:2-9c,12c, 18:2-9c,12c, and 12OH-18:1-9c, that were not present in the control (pESC-URA/blank) (Fig. 5). A comparison of the fatty acid profiles of yeast cells transformed with pESC-URA/CpFAH, pESC-URA/CpDGAT2/CpFAH, or pESC-URA/ScDga1/CpFAH showed that the coexpression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH resulted in a significantly higher level of ricinoleic acid than did the coexpression of ScDga1 and CpFAH, while the yeast strain expressing CpFAH alone produced the lowest level of ricinoleic acid (Fig. 5). These in vivo data provided further evidence that CpDGAT2 has a higher activity toward ricinoleic acid than does the native yeast DGAT2.

FIG. 5.

Coexpression of CpDGAT2 versus ScDga1 with CpFAH. (A) GC analysis of FAMEs from yeast S. cerevisiae H1246 cells expressing pESC-URA/blank, pESC-URA/CpDGAT2/CpFAH, pESC-URA/CpFAH, and pESC-URA/ScDga1/CpFAH constructs. (B) Fatty acid compositions of yeast S. cerevisiae H1246 cells expressing pESC-URA/blank, pESC-URA/CpFAH, pESC-URA/CpDGAT2/CpFAH, and pESC-URA/ScDga1/CpFAH. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Means with the same letters are not significantly different according to analysis of variance and Student's t test (n = 3; 18:1-9, P = 0.001; 18:2-9,12, P = 0.0001; 18:1-12OH, P = 0.002).

CpFAH is a bifunctional enzyme possessing both desaturase and hydroxylase activities on oleic acid, with hydroxylation activity predominating (20). The ratio of hydroxylation to desaturation activity was higher in yeast cells coexpressing CpFAH and CpDGAT2 than in cells expressing CpFAH and ScDga1 or CpFAH alone. The hydroxylation of oleic acid was approximately three times higher than the desaturation of oleic acid in pESC-URA/CpDGAT2/CpFAH and pESC-URA/ScDga1/CpFAH, whereas the ratio of hydroxylation to desaturation in yeast cells expressing CpFAH alone was close to 1.5:1 under the growth conditions used here (data not shown). The increase in the hydroxylation-to-desaturation ratio observed upon the expression of CpDGAT2 further implied that CpDGAT2 was more efficient in transferring the hydroxyl ricinoleic acid to triacylglycerols than was the native yeast DGAT2.

Expression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in various C. purpurea cell types.

Prior to analyzing the expression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in different types of cells, the fatty acid composition and quantity of TAGs in each cell type was determined. For TAG analysis, neutral lipids isolated from 5-, 10-, 20-, 25-, and 30-day-old cultures of sclerotium-like cells, 25-day-old cultures of mycelium cells, and conidial spores were separated by TLC, and the TAG fractions were quantified by GC. This analysis indicated that TAGs were the major class of neutral lipids in all types of C. purpurea cells, with sclerotium-like cells generally having a higher TAG content than other cell types (Table 1) while conidial spores had the smallest amount of TAGs. The largest amount of TAGs was obtained from sclerotium-like cells cultured for 20 days, followed by the 25-, 30-, and 10-day-old cultures. The TAG content of sclerotium-like cells cultured for only 5 days was lower than the TAG content of mycelium cells.

TABLE 1.

Quantity of fatty acids in TAGs isolated from 5 mg (dry weight) of different cell types of C. purpureaa

| Day of culture | Type of tissue | Total FA (μg) | 18:1-OH (μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Sclerotium | 20.38 ± 3.2 a | 0.45 ± 0.1 h |

| 10 | Sclerotium | 117.4 ± 18.1 b | 23.83 ± 3.3 i |

| 20 | Sclerotium | 415.4 ± 55.4 c | 137.0 ± 15.8 j |

| 25 | Sclerotium | 195.8 ± 26 d | 50.58 ± 6.8 k |

| 30 | Sclerotium | 155.8 ± 16.22 e | 47.07 ± 4.2 k |

| 40 | Conidial | 9.11 ± 0.5 f | |

| 25 | Mycelium | 65.96 ± 1.1 g |

Means with the same letters are not significantly different according to analysis of variance and Student's t test (P = 0.0001; n = 3).

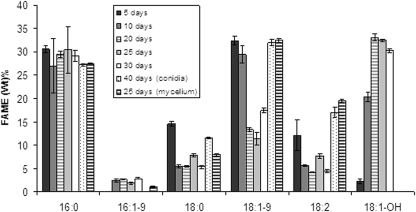

The fatty acid analysis of the TAG fractions indicated that ricinoleic acid was one of the major fatty acids in the TAG fraction of sclerotium-like cells, especially in the 20- and 25-day-old sclerotial cultures, where it represented 32 to 33% of the total fatty acid content of TAGs (Fig. 6). Conversely, the TAG fractions from conidial spores and mycelium cells did not contain hydroxyl fatty acids, and the major fatty acids found in these cells were oleic acid and palmitic acid. The analysis of the total cellular fatty acids revealed a slightly different pattern than that observed in the TAG fractions (data not shown). In total cellular fatty acids, linoleic acid was the most abundant fatty acid in mycelium cells and conidial spores, followed by oleic acid and palmitic acid. Levels of ricinoleic acid were highest in 10-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures, followed by 20-, 25-, and 30-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures.

FIG. 6.

Fatty acid composition of TAGs from 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-day-old cultures of sclerotium-like cells, 25-day-old cultures of mycelium, and 40-day-old cultures of conidial cells of C. purpurea.

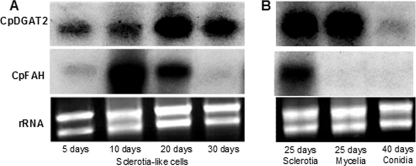

Northern blot analyses were performed to determine the expression levels of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH in different types of C. purpurea cells. Two separate membranes, one loaded with total RNA from 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures and the other loaded with total RNA from 25-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures, 25-day-old mycelial cell cultures, and conidiospores, were hybridized with CpDGAT2 and CpFAH probes. Membranes were hybridized initially with the CpDGAT2 probe and then stripped and rehybridized with the CpFAH probe. As shown in Fig. 7, CpDGAT2 was expressed in all sclerotium-like cells tested, with high expression commencing at 20 days of culture. CpDGAT2 also was highly expressed in mycelium cells but weakly expressed in conidiospore cells. CpFAH, like CpDGAT2, was expressed in all sclerotium-like cells; however, unlike CpDGAT2, the expression was highest in 10-day-old cell cultures, followed by 20-day-old cell cultures, and low but detectable levels of expression were observed in 5- and 30-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures. In contrast to CpDGAT2, CpFAH was not expressed in mycelium or conidial cells.

FIG. 7.

Northern blot expression analysis of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH. Approximately 7 μg of total RNA was loaded in each lane. (A) Northern blot analysis of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH transcripts in 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-day-old cultures of sclerotium-like cells. (B) Northern blot analysis of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH transcripts in 25-day-old cultures of sclerotium cells, 25-day-old cultures of mycelium cells, and conidial cells.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we described the molecular cloning by degenerate RT-PCR of a cDNA from the oleaginous fungus C. purpurea that encodes a type II acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase. The heterologous expression of the putative CpDGAT2 in S. cerevisiae strain H1246, in which all four genes involved in the biosynthesis of TAGs were disrupted, restored TAG biosynthesis in this TAG-deficient mutant. The analysis of the neutral lipids from the CpDGAT2-transformed yeast strain grown on a medium with exogenously administrated ricinoleic acid revealed the formation of TAGs with one hydroxyl fatty acid (monoricinolein) in the transformed yeast strain (Fig. 2). These data indicate that CpDGAT2 has the ability to use ricinoleic acid to synthesize ricinoleic acid-containing TAGs. The amount of monoricinolein in CpDGAT2-transformed yeast was higher than that in the wild-type yeast, despite the absence of the other three genes involved in TAG biosynthesis, implying that CpDGAT2 has a stronger substrate preference for ricinoleic acid than do the native yeast acyltransferase enzymes.

Results from an in vitro microsomal assay provided unambiguous evidence that CpDGAT2 preferentially acylates ricinoleic acid to diacylglycerol. When various radiolabeled acyl-CoAs were used as acyl donors and diolein was used as an acyl acceptor, CpDGAT2 had higher activity toward ricinoleic acid than toward the other fatty acids tested (Fig. 3). Further evidence of this enzyme's preferential utilization of ricinoleic acid as a substrate came from the coexpression experiments, which indicated that the simultaneous expression of CpDGAT2 and CpFAH produced a significantly higher level of ricinoleic acid than did the coexpression of the native yeast DGAT2 (ScDga1) with CpFAH. The amount of 18:1-9c in yeast carrying pESC-URA/CpDGAT2/CpFAH was relatively low compared to amounts found in yeast carrying pESC-URA/CpFAH or pESC-URA/ScDga1/CpFAH, indicating a higher efficiency in the conversion of 18:1-9c to 12OH-18:1-9c in the presence of CpDGAT2 (Fig. 4). These in vitro and in vivo data provide conclusive evidence that the CpDGAT2 isolated from C. purpurea has a substrate preference toward ricinoleic acid for TAG biosynthesis.

The substrate preference of CpDGAT2 toward ricinoleic acid was not unexpected, given that ricinoleic acid can represent up to 50% of the total fatty acids in the sclerotium oil of this fungus (2). DGAT2 previously has been implicated in the preferential utilization of unusual fatty acids for TAG formation. For example, yeast cells expressing tung tree DGAT2 produced higher levels of trielostearin than did cells expressing tung tree DGAT1 when fed with α-eleostearic acid, and the DGAT2 gene showed higher expression than the DGAT1 gene in developing seeds of tung, where the synthesis and storage of α-eleostearic acid occurs (26). The DGAT2 from castor beans showed a strong preference for ricinoleate-containing diacylglycerol substrates (5), while castor bean DGAT1 showed a greater preference toward diolein in in vitro assays (16). The coexpression of the castor DGAT2 with the castor hydroxylase resulted in a significant increase in ricinoleic acid production in transgenic seeds compared to the expression of the castor hydroxylase alone (5). However, neither castor DGAT2 nor any other DGAT2 enzyme has been shown to preferentially utilize ricinoleic acid as an acyl donor. To our knowledge, this is the first report that provides unambiguous evidence from both in vitro and in vivo assays showing the preferential utilization of an unusual fatty acid as an acyl donor for TAG formation by a type II diacylglycerol acyltransferase.

The lipid analysis of different types of cells, such as mycelia, conidiospores, and various stages of sclerotium-like cells from C. purpurea, indicated that larger amounts of TAGs were found in sclerotium-like cells of C. purpurea, while other types of cells, especially conidiospores, accumulated much lower levels of TAGs. This coincides with the role of the sclerotium as an energy storage tissue, representing the life cycle stage in which the fungus overwinters (9). The amount of TAGs in sclerotium-like cells reaches a maximum in 20-day-old cultures, followed by 25- and 30-day-old cultures, with the smallest amount being harvested from 40-day-old cultures. The small amount of TAGs in the 40-day-old cultures may be due to the fact that C. purpurea does not follow its normal life cycle under the axenic culture conditions used here. While in natural conditions sclerotia germinate to form stroma with ascospores, late-stage sclerotium-like cells in axenic cultures differentiate into conidial spores, and the C. purpurea sexual stage cannot be obtained in these cultures (13). Generally, ricinoleic acid was the major fatty acid found in sclerotium-like cells, with the exception of sclerotium-like cells at the earliest stage of culture. Ricinoleic acid was not detected in mycelium cells or conidial spores. Although mycelium cultures grown in ANM were reported to produce a small amount of ricinoleic acid (19), mycelium cells grown in PDA medium as in our experiments did not produce this fatty acid, nor were mycelium cells able to differentiate into sclerotium-like cells regardless of the length of cultivation in this medium. The large amount of ricinoleic acid found in the TAG fraction of the 10-, 20-, 25-, and 30-day-old sclerotium-like cell cultures implies that both CpFAH and CpDGAT2 must be expressed in these tissues. Northern blot analysis of these cells indicated that the expression pattern of these two genes did indeed correlate well with the lipid accumulation pattern. CpFAH was expressed solely in sclerotium cells where ricinoleic acid is accumulated, and transcripts were not detected in mycelial or conidial spores, in which little or no ricinoleic acid is produced. CpDGAT2 showed wider expression among the cell types examined, with the exception of conidial spores, where both CpDGAT2 transcript levels and TAG levels were low. In general, the increased expression of CpDGAT2 was observed in lipid samples with high TAG levels. This was especially true with sclerotium cells, where a higher level of ricinoleate TAGs is accumulated. The high expression of both CpFAH and CpDGAT2 along with the high level of accumulation of ricinoleate TAGs in the 20- and 30-day-old sclerotium cultures is consistent with CpDGAT2 and CpFAH functioning as key enzymes in the biosynthesis of ricinoleate-containing TAGs in C. purpurea.

Hydroxyl fatty acids, in particular ricinoleic acid, recently have been the subject of a high level of scientific interest because of their many industrial uses in the manufacture of various environmentally friendly bioproducts. The metabolic engineering of oilseeds to produce ricinoleic acid has been viewed as an attractive alternative method for obtaining a large quantity of this fatty acid for industrial applications. Four genes encoding oleate hydroxylases involved in the synthesis of ricinoleic acids have been identified, three from plants (4, 12, 29) and one from a fungal species (21). The introduction of these hydroxylases into plants led to the production of substantial amounts of ricinoleic acid in seeds, but the levels attained to date still are much lower than those found in the native species from which the genes originated (4, 12, 28, 29). This implies that additional factors, which may have coevolved along with the biosynthetic pathway for this fatty acid, are required for the production of high levels of hydroxyl fatty acids in transgenic plants. A recent study showed that the expression of a castor bean DGAT2 along with the corresponding oleate hydroxylase in Arabidopsis resulted in an increase in the production of ricinoleic acid in transgenic seeds, suggesting that triglyceride assembly plays important roles in the production of unusual fatty acids. This report adds a new DGAT2 of fungal origin that has a clear substrate preference for ricinoleic acid in TAG synthesis, making it an attractive candidate for the metabolic engineering of high levels of hydroxyl fatty acids in oilseed crops.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Stuhl. 1998. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- 2.Batrakov, S. G., and O. N. Tolkacher. 1997. The structures of triacylglycerols from sclerotia of the rye ergot Claviceps purpurea (fries) Tul. Chem. Phys. Lipids 86:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the detection of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broun, P., and C. Somerville. 1997. Accumulation of ricinoleic, lesquerolic, and densipolic acids in seeds of transgenic Arabidopsis plants that express a fatty acid hydroxylase cDNA from castor bean. Plant Physiol. 113:933-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgal, J., J. Shockey, C. Lu, J. Dyer, T. Larson, I. Graham, and J. Browse. 2008. Metabolic engineering of hydroxyl fatty acid production in plants: RcDGAT2 drives dramatic increases in ricinoleate levels in seed oil. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cases, S., S. J. Stone, P. Zhou, E. Yen, B. Tow, K. D. Lardizabal, T. Voelker, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 2001. Cloning of DGAT2, a second mammalian diacylglycerol acyltransferase, and related family members. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38870-38876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cases, S., S. J. Smith, Y. Zheng, H. M. Myers, S. R. Lear, E. Sande, S. Novak, C. Collins, C. B. Welch, A. J. Lusis, S. K. Erickson, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 1998. Identification of a gene encoding an acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltranferase, a key enzyme in triacylglycerol synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:13018-13023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, H. C., S. J. Smith, B. Tow, P. M. Elias, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 2002. Leptin modulates the effect of acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase deficiency on murine fur and sebaceous glands. J. Clin. Invest. 109:175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbett, K., A. G. Dickerson, and P. G. Mantle. 1975. Metabolism of the germinating sclerotium of Claviceps purpurea. J. Gen. Microbiol. 90:55-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, L. G., M. D. Dibner, and J. F. Battey. 1986. Basic methods on molecular biology, 1st ed. Elsevier Science Publishing Co., New York, NY.

- 11.Donaldson, R. P. 1977. Accumulation of free ricinoleic acid in germinating castor bean endosperm. Plant Physiol. 59:1064-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duak, M., P. Lam, L. Kunst, and M. A. Smith. 2007. A FAD2 homologue from Lesquerella lindheimeri has predominantly fatty acid hydroxylase activity. Plant Sci. 172:43-49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esser, K., and P. Tudzynski. 1978. Genetics of the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 53:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by the Liac/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Enzymol. 350:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, X. H., G. O. Chen, J. T. Lin, and T. A. McKeon. 2006. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity and triacylglycerol synthesis in germinating castor seed cotyledons. Lipids 41:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He, X. H., C. Turner, G. Q. Chen, J. T. Lin, and T. A. McKeon. 2004. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding diacylglycerol acyltransferase from castor bean. Lipids 39:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroon, J. T., W. Wei, W. J. Simon, and A. R. Slabas. 2006. Identification and functional expression of a type 2 acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT2) in developing castor bean seeds which has high homology to the major triglyceride biosynthetic enzyme of fungi and animals. Phytochemistry 67:2541-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lardizabal, D. K., T. J. Mai, W. Wagner, A. Wyrick, T. Voelker, and J. D. Hawkins. 2001. DGAT2 in a new diacylglycerol acytransferase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38862-38869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantle, P. G., and L. J. Nisbet. 1976. Differentiation of Claviceps purpurea in anexic cultures. J. Gen. Microbiol. 93:321-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meesapyodsuk, D., and X. Qiu. 2008. An oleate hydroxylase from the fungus Claviceps purpurea: cloning, functional analysis, and expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147:1325-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meesapyodsuk, D., W. D. Reed, S. P. Covello, and Q. Xiao. 2007. Primary structure, regioselectivity, and evolution of the membrane-bound fatty acid desaturases of Claviceps purpurea. J. Biol. Chem. 282:20191-20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pillai, M. G., M. Certik, T. Nakahara, and Y. Kamisaka. 1998. Characterization of triacylglycerol biosynthesis in subcellular fractions of an oleaginous fungus, Mortierella ramanniana var. angulispora. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1393:128-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed, W. D., A. U. Schafer, and S. P. Covello. 2000. Characterization of the Brassica napus extraplastidial linoleate desaturase by expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant Physiol. 122:715-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Routaboul, J.-M., C. Benning, N. Bechtold, M. Caboche, and L. Lepiniec. 1999. The TG1 locus of Arabidopsis encodes for a diacylglycerol acyltransferase. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 37:831-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandager, L., H. M. Gustavsson, U. Stahl, A. Dahlqvist, E. Wiberg, A. Banas, M. Lenman, H. Ronne, and S. Stymne. 2002. Storage lipid synthesis is non-essential in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6478-6482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shockey, J. M., S. K. Gidda, D. C. Chapital, J.-C. Kuan, P. K. Dhanoa, J. M. Bland, S. J. Rothstein, R. T. Mullen, and J. M. Dyer. 2006. Tung tree DGAT1 and DGAT2 have nonredundant functions in triacylglycerol biosynthesis and are localized to different subdomains of the endoplastic reticulum. Plant Cell 18:2294-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith, S. J., S. Cases, D. R. Jensen, H. C. Chen, E. Sande, B. Tow, D. A. Sanan, J. Raber, R. H. Eckel, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 2000. Obesity resistance and multiple mechanisms of triglyceride synthesis in mice lacking Dgat. Nat. Genet. 25:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, M. A., and H. Moon. 2003. Heterologous expression of a fatty acid hydroxylase gene in developing seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 217:507-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van de Loo, F. J., P. Broun, S. Turner, and C. Somerville. 1995. An oleate 12-hydroxylase from Ricinus communis L. is a fatty acyl desaturase homolog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:6743-6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss, S. B., E. P. Kennedy, and E. J. Kiyasu. 1960. The enzymatic synthesis of triglycerides. J. Biol. Chem. 235:40-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen, C. E., M. Monetti, B. J. Burri, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 2005. The triacylglycerol synthesis enzyme DGAT1 also catalyzes the synthesis of diacylglycerols, wax, and retinyl esters. J. Lipid Res. 46:1502-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yen, C.-L. E., S. J. Stone, S. Koliwad, C. Harris, and R. V. Farese, Jr. 2008. DGAT enzymes and triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 49:2283-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]