Abstract

Notch signalling represents a key pathway essential for normal vascular development. Recently, great attention has been focused on the implication of Notch pathway components in postnatal angiogenesis and regenerative medicine. This paper critically reviews the most recent findings supporting the role of Notch in ischaemia-induced neovascularization. Notch signalling reportedly regulates several steps of the reparative process occurring in ischaemic tissues, including sprouting angiogenesis, vessel maturation, interaction of vascular cells with recruited leucocytes and skeletal myocyte regeneration. Further characterization of Notch interaction with other signalling pathways might help identify novel targets for therapeutic angiogenesis.

Keywords: hypoxia, ischaemic disease, Notch intracellular domain, Notch signalling, therapeutic angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

Introduction

In the Western world, ischaemic disease is highly prevalent and is associated with elevated morbidity and mortality. Critical limb ischaemia is the end-stage outcome of multiple types of peripheral artery disease, especially in patients with diabetes [1,2]. Coronary artery disease is responsible for deterioration of cardiac function through acute cardiomyocyte loss and maladaptive remodelling after myocardial infarction. Under both conditions, the extent of recovery is dependent on the residual ability of the organism to build up a feeding vascular tree. Following occlusion of a major artery, two different types of vascular growth participate in the salvage of ischaemic tissue, namely sprouting of capillaries (angiogenesis) and growth of collateral arteries from preexisting arterioles (arteriogenesis) [3,4]. The concept of therapeutic angiogenesis in ischaemic disease relies on supporting endogenous vascular growth to improve the tissue perfusion [5-7]. Induction of therapeutic angiogenesis by administration of angiogenic morphogens such as VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) remains a promising approach despite the partial success of clinical trials, which did not confirm the remarkable results of pre-clinical studies [8,9]. One of the reasons accounting for this discrepancy is that delivery of single growth factors may represent a simplification of the cooperative molecular interaction necessary for the establishment of a functional vascular network [10]. For instance, new findings underline the importance of cross-talk between Notch signalling components and VEGF in building up a proper neovascularization. The present review summarizes the role of Notch signalling in main aspects of the reparative vascular response to ischaemic injury.

The Notch signalling pathway and vascular development

Notch signalling is an evolutionarily conserved intercellular pathway controlling cell differentiation, cell fate specification and patterning during embryonic and postnatal development [11]. In mammals, the pathway encompasses five transmembrane ligands: Dll1 (Delta-like 1), Dll3, Dll4, Jag1 (Jagged-1) and Jag2, and four single-pass transmembrane receptors, Notch1–Notch4. Activation of Notch by its ligands initiates a series of successive proteolytic cleavages. First, extracellular cleavage of Notch occurs by TACE [TNFα (tumour necrosis factor α)-converting enzyme; also called ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) 17] and Kuzbanian (ADAM10), two members of the ADAM family. This is followed by transmembrane cleavage by γ -secretase [12], releasing the NICD (Notch intracellular domain), which next translocates to the nucleus and forms a complex with the transcriptional regulator RBP-Jκ (recombinant signal-binding protein 1 for Jκ). In the absence of Notch signalling, RBP-Jκ associates with transcriptional co-repressors that actively keep target gene expression shut down. Binding of NICD to RBP-Jκ replaces the co-repressor transcriptional complex with a co-activator complex, which in turn triggers the transcription of Notch target genes such as bHLH (basic helix–loop–helix) proteins: Hes (hairy/enhancer of split), Hey (Hes-related protein) and Nrarp (Notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein). These transcription factors regulate further downstream genes to respond to environmental stimuli, either by maintaining cells in an uncommitted state or by inducing differentiation depending on cell type [13].

Most Notch pathway components are expressed and have a critical role during vascular development [14-17]. Functional studies using genetically modified animals have provided us with convincing evidence that Notch signalling plays a key role in the whole process of developmental angiogenesis (summarized in Table 1). In very early embryogenesis, Notch signalling modulates the migration of a subpopulation of angioblasts from the lateral mesoderm towards the dorsal aorta and induces their specification to endothelial cells [18]. In later stages, Notch signalling controls endothelial cell specification into arterial or venous identity. Activation of Notch in the endothelium results in induction of its downstream effector EphrinB2 and suppression of EphB4 expression, thereby establishing arterial identity. Conversely, when the Notch signalling pathway is suppressed by COUPTFII (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II), vessels acquire vein identity [19]. The Dll1 ligand seemingly mediates arterial identity acquisition [20].

Table 1. Vascular defects in genetically modified mice for components of the Notch pathway E, embryonic day.

| Genotype | Phenotype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Receptors | ||

| Notch1−/− | Lethality at E11.5 | Krebs et al. [15] |

| No apparent defects in vasculogenesis | ||

| Defect in angiogenic remodelling: disorganized, confluent vascular plexus blood vessels in the yolk sac | ||

| Collapsed dorsal aorta Defect of the anterior cardinal vein Malformation of inter-somitic vessels | ||

| Notch2−/− | Prenatal lethality | McCright et al. [59] |

| Widespread haemorrhage near the surface of the skin | ||

| No capillary tuft of mature glomeruli | ||

| Capillary aneurysm-like structure of glomeruli | ||

| Notch3−/− | Viable | Domenga et al. [45] |

| Arteries are enlarged and exhibit less festooned elastic laminae | ||

| Impaired postnatal maturation of arteries | ||

| VSMCs have an irregular shape and form abnormal clusters of poorly oriented cells towards the lumen | ||

| Reduced expression of smooth muscle differentiation markers: smoothelin and SM22α | ||

| Impaired cerebral blood flow reactivity | ||

| Notch1−/− /Notch4−/− | More severe phenotype than Notch1-null mutant | Krebs et al. [15] |

| Ligands | ||

| Dll1+/− | Arterial endothelial and smooth muscle markers are down-regulated in fetal large arteries [52] | Limbourg et al. [52]; |

| Impaired postnatal arteriogenesis, but not microvascular angiogenesis | Sörensen et al. [20] | |

| Dll4+/− | Lethality at E10.5 | Gale et al. [61]; Durate et al. [14]; Hellstrom et al. [26] |

| Defect in angiogenic remodelling of yolk sac vessels | ||

| Reduction of the calibre of the dorsal aorta | ||

| Defective arterial branching from the aorta | ||

| Occasional extension of the defects to the venous circulation when severe defects occur in arterial circulation (secondary effect) | ||

| Loss of endothelial arterial markers: EphrinB2 | ||

| Postnatal angiogenesis (retina vasculature) | ||

| Abnormal branching morphogenesis and increased vascular network density | ||

| Increased numbers of filopodia-extending endothelial tip cells Increased numbers of tip cells in the angiogenic front | ||

| Dll4−/− | Lethality at E9.5 | Durate et al. [14]; Benedito et al. [60] |

| More severe embryonic vascular defects than heterozygotes | ||

| Defective basement membrane around the forming aorta | ||

| Jag1−/− | Lethality at 11.5 | Xue et al. [62] |

| Lack of obviously large vessels and failure to remodel the primary plexus in the yolk sac | ||

| Widespread haemorrhage, in particular in the cranial mesenchyme Less intricate network and a reduced diameter of vessels in the head | ||

| Effectors | ||

| Hey1−/−/Hey2−/− | Lethality at E9.5 | Fischer et al. [63] |

| No defect in vasculogenesis | ||

| Placental labyrinth completely lacks embryonic blood vessels | ||

| The vessels of the yolk sac are either small or absent | ||

| Lack of vascular remodelling and massive haemorrhage | ||

| Defect in the major vessels: dorsal aorta | ||

| Large arteries failed to express arterial markers: CD44, Nrp1 and EphrinB2 | ||

| Nrarp−/− | Viable | Phng et al. [29] |

| Delay in radial expansion of growing retina vessels | ||

| Increased vessel regression in retina | ||

| Discontinuous endothelial junctions in retina vessels |

Regulation of endothelial cell sprouting by Notch signalling

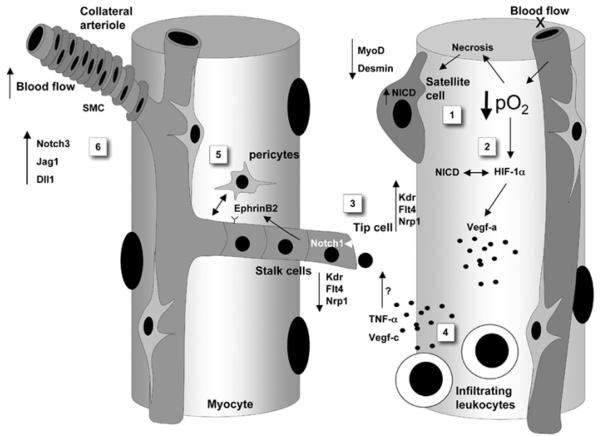

The contribution of Notch in postnatal angiogenesis is the focus of intense investigation, particularly in the field of tumour vascularization. It is now becoming clear that Notch signalling guides the initiation and stabilization of sprouting angiogenesis on hypoxia induction. Ischaemia triggers endogenous sprouting of capillaries into the damaged area to overcome hypoxia and starvation. The formation of new sprouts requires selection of a distinct site on the vessel where endothelial cells start to invade the surrounding tissue or matrix, whereas neighbouring cells along the vessels must be static ‘stalk cells’. Specialized endothelial cells, called ‘tip cells’, taking the leader role of directing the outgrowth of blood vessel sprouts, are guided by the gradient of VEGFA [21], but also rely on Dll4–Notch signals exchanged with other endothelial cells to restrict the emergence of too many sprouts through repression of VEGFR-2 [Kdr (kinase insert domain-containing receptor)], VEGFR-3 [Flt4 (Fms-like tyrosine kinase 4)] and Nrp1 (neuropilin-1) in stalk cells, and consequent reduction of the responsiveness to VEGF (Figure 1) [22-25]. Conversely, suppression of Notch signalling by γ -secretase inhibitor treatment or genetic deletion of Dll4 allele in mouse or zebrafish increases the number of sprouting endothelial cells and this eventually leads to a highly dense branching vascular network [24,26]. Consistent with this, suppression of Notch results in increased endothelial cell proliferation in in vitro three-dimensional assays [23,27]. The inhibitory effect of Notch on endothelial cell proliferation is mediated through the MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)/PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/Akt (also called protein kinase B) pathway [28]. Taken together, Notch signalling seems to be essential in governing the transition from active angiogenesis to quiescence. Modulators of this important function are now recognized. For instance, the loss of Nrarp (Notch downstream gene) leads to increased activity of Notch, reduces the proliferation of stalk cells and stimulates excessive junctional rearrangement within stalk cells. Indeed, Nrarp functions as a negative regulator of Notch by inducing NICD degradation. It has been suggested that Nrarp could play a role in stabilizing the connection between new formed stalk cells by co-ordinating Notch and Wnt signalling pathways [29].

Figure 1. Notch signalling and cellular components involved in the post-ischaemic regenerative process.

Decreased oxygen levels (hypoxia) resulting from arterial occlusion activates Notch signalling in satellite cells (1), which results in expansion of satellite cells and reduced expression of myogenic differentiation genes, MyoD and desmin. Furthermore, hypoxia triggers the expression HIF-1α (2), which subsequently binds to NICD and enhances the transcription of Notch target genes. In hypoxic areas, VEGF-A production is activated by HIF-1α through binding to the VEGF promoter. Endothelial cells exposed to the VEGF-A gradient express Dll4 and are selected as tip cells that sprout and send filopodia (3). Endothelial tip cells use Dll4 to activate Notch on neighbouring stalk cells and thereby suppress the expression of the VEGF receptors Kdr, Flt4 and Nrp1. This prevents stalk cells from acquiring a tip cell phenotype. Infiltrating leucocytes may amplify the angiogenic response by secreting VEGF-C and TNFα (4). TNFα induces the expression of Jag1 on tip cells. VEGF-C binds Flt4, which is highly expressed in tip cells. Activation of Notch in stalk cells allows for recruitment of mural cells (pericytes), through a mechanism involving EphrinB2, and stabilization of neovascularization (5). Vascular maturation is also supported with the contribution of Notch3 and Dll1 in the recruitment of VSMCs of collateral arterioles (6). Kdr, VEGFR-2; Flt4, VEGFR-3.

The guidance of sprouting angiogenesis by the Notch/Dll4 duo was illustrated in murine tumour models. Several preclinical studies have shown that blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by inducing immature angiogenesis, which consists of excessive tip cell formation and is functionally incompetent, leading to poor perfusion and enhanced hypoxia [30-32]. Evidence accumulated so far supports the notion of an endothelium-specific action of Dll4/Notch signalling in the regulation of cell interaction. The possibility that the mechanism is also relevant for the cross-talk between endothelial cells and components of the surrounding tissue, including tumour cells, stromal cells and invading leucocytes, remains mostly unexplored.

One possible scenario proposes the modulation of Notch signalling components on endothelial cells by paracrine mediators released by neighbouring cells. Of note, recent studies have shown that the inflammatory cytokine TNFα can induce an endothelial tip cell phenotype highly enriched with Notch ligand Jag1 but not Dll4 ligand [33]. Furthermore, the induction of Jag1 expression is mediated by the NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) pathway when endothelial cells are stimulated by TNFα [34]. This suggests that Jag1 may play a similar role in sprouting angiogenesis under inflammatory conditions as Dll4 does during development and tumour angiogenesis. In addition, it has been previously reported that Jag1 is expressed at the leading edge of repairing vessels: under ischaemic conditions, recruited leucocytes could modulate angiogenesis through the secretion of growth factors and cytokines, conferring a sprouting phenotype on resident endothelial cells [35]. Another scenario has leucocytes establishing cell–cell contacts with sprouting endothelial cells during angiogenesis in ischaemic tissues. The possibility that this physical interaction involves Notch signalling components expressed on leucocytes and endothelial cells is supported by studies using soluble Notch ligands, which result in excessive inflammation and disordered angiogenesis (A. Al Haj Zen, unpublished work). Further investigation is therefore needed to elucidate the functional consequences of disrupting Notch-mediated interactive contacts in the context of ischaemia.

Notch signalling in the hypoxic environment

Growing evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies shows that hypoxic signalling overlaps Notch signalling in various pathological conditions. HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor-1) is a major transcription factor that functions as a master regulator of oxygen homoeostasis. HIF-1 regulates the expression of angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF [36]. The study by Gustafsson et al. [37] demonstrated that the maintenance of myogenic satellite cells in an undifferentiated state during hypoxia depends on Notch signalling. This might involve a direct interaction between HIF-1α and NICD. It was shown that the formation of the complex NICD–HIF-1α stabilizes NICD and enhances its binding with Notch-target promoters [37]. An additional mechanism of cross-talk is revealed by the interaction between NICD and the protein FIH-1 (factor inhibiting HIF-1α). FIH-1 can suppress the intracellular level of HIF-α by hydroxylation. Interestingly, FIH-1 is also able to hydroxylate NICD [38]. As FIH-1 shows more affinity in binding NICD than HIF-1α, FIH-1 is sequestered away from HIF-1α. In this way, activated Notch signalling indirectly enhances HIF-1α recruitment to the HIF-response promoter, which enhances the expression of HIF-1α-responsive genes [39]. A relevant role in this context could be also played by Notch ligands. Indeed, hypoxia induces the expression of Dll4 in endothelial cells, leading to increased Notch signalling on neighbouring cells [40]. Whereas the induction of Notch signalling by hypoxia in different tumour cell types is well defined [41,42], more studies are required to establish whether expression of Notch signalling components follows the hypoxic gradient established after arterial occlusion. If this is the case, Notch-expressing tip cells might first emerge in the most hypoxic region to establish connections with perfused vessels of the border zone.

Notch signalling and mural cells

Mural cells influence blood vessel assembly by controlling events such as endothelial cell proliferation, migration, sprouting and regression. Direct cell–cell contact has also been shown to play a role in endothelial/mural cell cross-talk during angiogenesis [43]. Endothelial-specific knockout of the Jag1 gene gives rise to an embryonic lethal phenotype, interestingly, with an absence of α-SMC (α-smooth muscle cell) actin expression in the vasculature [44]. Conversely, absence of Notch3 results in enlarged arteries with abnormal distribution of elastic laminae, indicating that VSMC (vascular smooth muscle cell) differentiation is impaired [45]. In this way, Notch3 signalling through the ligand Jag1 expressed on neighbouring endothelial cells maintains vascular support cells in a differentiated phenotype [46]. Primary culture studies of VSMCs demonstrated that Notch signalling activated by Jag1 can induce directly or indirectly VSMC differentiation genes such as α-SMC actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and PDGFRβ (platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β) [47-49].

The importance of Notch3 signalling in VSMC differentiation was determined in human pathology. Indeed, mutations of Notch3 cause CADASIL disease (named after cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) characterized by a late-onset disorder causing stroke and dementia, which arises from slowly developing systemic vascular lesions ultimately resulting in the degeneration of VSMCs [50]. Furthermore, Notch signalling could play a functional role in controlling the proliferation of VSMCs. Cultured VSMCs from Hey2-deficient mice showed a decrease in their proliferation rate compared with wild-type cells. This effect is mediated by p27kip1 since Hey2 protein can directly bind p27kip1 promoter to repress transcription [51]. Arteriogenesis depends on VSMC proliferation and migration and extracellular matrix accumulation. In this setting, Dll1 binding to Notch seems to affect arteriogenesis more than capillary angiogenesis. Indeed, Dll1 heterozygous mice show impaired collateral arteries formation and delayed limb perfusion recovery after femoral artery ligation [52].

Notch signalling and skeletal-muscle regeneration

Chronic limb ischaemia results in cell death that triggers a cascade of events leading to myogenesis induction [53]. Regeneration of damaged muscle fibres is achieved almost exclusively by satellite cells, which represent resident progenitors in the adult skeletal muscle. On ischaemic damage, satellite cells are activated and transit to the actively proliferative state [54]. They can generate daughter cells that differentiate into fusion-competent myoblasts to promote repair and regeneration. Ex vivo experiments showed that Notch1 is expressed in quiescent satellite cells; however, NICD, an indicator of Notch activity, appears only after satellite cell activation. Moreover, forced expression of NICD alone is able to induce proliferation of satellite cells and to attenuate the myogenic differentiation by up-regulating Pax3 and down-regulating MyoD and desmin [55]. In conditional RBP-Jκ mutant mice, the satellite cells are not formed in the late stage of fetal development [56].

In the study by Conboy et al. [57], insufficient activation of Notch1 by Dll1 is detected in old animals and contributes to the loss of regenerative potential of skeletal muscle. In myoblasts, the level of Notch activity seems to be closely regulated by the transcription factor Stra13. Moreover, Stra13 expression is essential in the late stages of muscle regeneration to surmount the activity of Notch signalling, thereby reducing myoblast proliferation and promoting myogenic differentiation. Indeed, on injury, Stra13-knockout mice exhibit increased cellular proliferation, elevated Notch signalling and a striking regeneration defect characterized by degenerated myotubes, increased mononuclear cells and fibrosis [58]. Thus the tight temporal regulation of Notch activity is vital for efficient muscle regeneration. This issue might have practical consequences when considering Notch as a potential therapeutic target for the cure of ischaemic disease. The optimal strategy should attempt to co-ordinate Notch's influence on angiogenesis and myogenesis to restore tissue integrity.

Conclusions and perspectives

Studies reviewed in the present paper indicate that the function of Notch signalling is ligand and context dependent. For example, Notch1 signalling activated by Dll4 ligand is essential to determine the fate of endothelial cells whether this is a stalk cell (non-migratory) or a tip cell (migratory). In contrast, Notch signalling activated by Dll1 and Jag1 is important for VSMC differentiation. Under inflammatory conditions, it is the ligand Jag1 that takes the role of stimulating the formation of tip endothelial cells.

The function of the canonical Notch signalling pathway was revealed thanks to seminal studies in embryogenesis. The challenge is now to understand the role of this pathway in adult angiogenesis under physiological and pathological conditions, with the aim of exploiting the therapeutic potential of Notch and its ligands for the cure of ischaemic disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This review was financially supported by the British Heart Foundation [grant number PG/06/035/20641].

Abbreviations used

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- Dll1

Delta-like 1

- Flt4

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 4

- HIF-1

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- FIH-1

factor inhibiting HIF-1α

- Jag1

Jagged-1

- kdr

kinase insert domain-containing receptor

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- Nrarp

Notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein

- Nrp1

neuropilin-1

- RBP-Jκ

recombinant signal-binding protein 1 for Jκ

- α-SMC

α-smooth muscle cell

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

References

- 1.Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. Circulation. 2004;110:738–743. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137913.26087.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slovut DP, Sullivan TM. Critical limb ischaemia: medical and surgical management. Vasc. Med. 2008;13:281–291. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08091485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heilmann C, Beyersdorf F, Lutter G. Collateral growth: cells arrive at the construction site. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002;10:570–578. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(02)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanueli C, Madeddu P. Therapeutic angiogenesis: translating experimental concepts to medically relevant goals. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2006;45:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshita S, Pu LQ, Stein LA, Sniderman AD, Bunting S, Ferrara N, Isner JM, Symes JF. Intramuscular administration of vascular endothelial growth factor induces dose-dependent collateral artery augmentation in a rabbit model of chronic limb ischaemia. Circulation. 1994;90:II228–II234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone OA, Richer C, Emanueli C, van Weel V, Quax PH, Katare R, Kraenkel N, Campagnolo P, Barcelos LS, Siragusa M, et al. Critical role of tissue kallikrein in vessel formation and maturation: implications for therapeutic revascularization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:657–664. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanueli C, Salis MB, Pinna A, Graiani G, Manni L, Madeddu P. Nerve growth factor promotes angiogenesis and arteriogenesis in ischemic hindlimbs. Circulation. 2002;106:2257–2262. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033971.56802.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry TD, Annex BH, McKendall GR, Azrin MA, Lopez JJ, Giordano FJ, Shah PK, Willerson JT, Benza RL, Berman DS, et al. The VIVA trial: vascular endothelial growth factor in ischaemia for vascular angiogenesis. Circulation. 2003;107:1359–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061911.47710.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons M, Ware JA. Therapeutic angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:863–871. doi: 10.1038/nrd1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons M. Angiogenesis: where do we stand now? Circulation. 2005;111:1556–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159345.00591.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai EC. Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate. Development. 2004;131:965–973. doi: 10.1242/dev.01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duarte A, Hirashima M, Benedito R, Trindade A, Diniz P, Bekman E, Costa L, Henrique D, Rossant J. Dosage-sensitive requirement for mouse Dll4 in artery development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2474–2478. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, Sundberg JP, Gallahan D, Closson V, Kitajewski J, Callahan R, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roca C, Adams RH. Regulation of vascular morphogenesis by Notch signaling. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2511–2524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1589207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y, Watanabe T, Saito D, Takahashi T, Yoshida S, Kohyama J, Ohata E, Okano H, Takahashi Y. Notch mediates the segmental specification of angioblasts in somites and their directed migration toward the dorsal aorta in avian embryos. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:890–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You LR, Lin FJ, Lee CT, DeMayo FJ, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. Suppression of Notch signalling by the COUP-TFII transcription factor regulates vein identity. Nature. 2005;435:98–104. doi: 10.1038/nature03511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sörensen I, Adams RH, Gossler A. DLL1-mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood. 2009;113:5680–5688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D, Betsholtz C. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhardt H, Ruhrberg C, Abramsson A, Fujisawa H, Shima D, Betsholtz C. Neuropilin-1 is required for endothelial tip cell guidance in the developing central nervous system. Dev. Dyn. 2004;231:503–509. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature. 2007;445:781–784. doi: 10.1038/nature05577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie JD, Ariza-McNaughton L, Bermange AL, McAdow R, Johnson SL, Lewis J. Endothelial signalling by the Notch ligand Delta-like restricts angiogenesis. Development. 2007;134:839–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.003244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tammela T, Zarkada G, Wallgard E, Murtomäki A, Suchting S, Wirzenius M, Waltari M, Hellström M, Schomber T, Peltonen R, et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature. 2008;454:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature07083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellström M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, Wallgard E, Coultas L, Lindblom P, Alva J, Nilsson AK, Karlsson L, Gaiano N, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;445:776–780. doi: 10.1038/nature05571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sainson RC, Aoto J, Nakatsu MN, Holderfield M, Conn E, Koller E, Hughes CC. Cell-autonomous notch signaling regulates endothelial cell branching and proliferation during vascular tubulogenesis. FASEB J. 2005;19:1027–1029. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3172fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu ZJ, Xiao M, Balint K, Soma A, Pinnix CC, Capobianco AJ, Velazquez OC, Herlyn M. Inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation by Notch1 signaling is mediated by repressing MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways and requires MAML1. FASEB J. 2006;20:1009–1011. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4880fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phng LK, Potente M, Leslie JD, Babbage J, Nyqvist D, Lobov I, Ondr JK, Rao S, Lang RA, Thuston G, Gerhardt H. Nrarp coordinates endothelial Notch and Wnt signaling to control vessel density in angiogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway J, Zhang G, Wu Y, Stawicki S, Liang WC, Chanthery Y, Kowalski J, Watts RJ, Callahan C, Kasman I, et al. Inhibition of Dll4 signalling inhibits tumour growth by deregulating angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444:1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/nature05313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, Coetzee S, Boland P, Gale NW, Lin HC, Yancopoulos GD, Thurston G. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JL, Sainson RC, Shi W, Leek R, Harrington LS, Preusser M, Biswas S, Turley H, Heikamp E, Hainfellner JA, Harris AL. Delta-like 4 Notch ligand regulates tumor angiogenesis, improves tumor vascular function, and promotes tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11244–11253. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sainson RC, Johnston DA, Chu HC, Holderfield MT, Nakatsu MN, Crampton SP, Davis J, Conn E, Hughes CC. TNF primes endothelial cells for angiogenic sprouting by inducing a tip cell phenotype. Blood. 2008;111:4997–5007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston DA, Dong B, Hughes CC. TNF induction of jagged-1 in endothelial cells is NFκB-dependent. Gene. 2009;435:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindner V, Booth C, Prudovsky I, Small D, Maciag T, Liaw L. Members of the Jagged/Notch gene families are expressed in injured arteries and regulate cell phenotype via alterations in cell matrix and cell–cell interaction. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:875–883. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61763-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semenza GL. HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman ML, McDonough MA, Hewitson KS, Coles C, Mecinovic J, Edelmann M, Cook KM, Cockman ME, Lancaster DE, Kessler BM, et al. Asparaginyl hydroxylation of the Notch ankyrin repeat domain by factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24027–24038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng X, Linke S, Dias JM, Zheng X, Gradin K, Wallis TP, Hamilton BR, Gustafsson M, Ruas JL, Wilkins S, et al. Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:3368–3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711591105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel NS, Li JL, Generali D, Poulsom R, Cranston DW, Harris AL. Up-regulation of Delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8690–8697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jogi A, Ora I, Nilsson H, Lindeheim A, Makino Y, Poellinger L, Axelson A, Pahlman S. Hypoxia alters gene expression in human neuroblastoma cells toward an immature and neural crest-like phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:7021–7026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102660199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bedogni B, Warneke JA, Nickoloff BJ, Giaccia AJ, Powell MB. Notch1 is an effector of Akt and hypoxia in melanoma development. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3660–3670. doi: 10.1172/JCI36157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaengel K, Genové G, Armulik A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-mural cell signaling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:630–638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.High FA, Lu MM, Pear WS, Loomes KM, Kaestner KH, Epstein JA. Endothelial expression of the Notch ligand Jagged1 is required for vascular smooth muscle development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1955–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709663105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Domenga V, Fardoux P, Lacombe P, Monet M, Maciazek J, Krebs LT, Klonjkowski B, Berrou E, Mericskay M, Li Z, et al. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2730–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.308904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu H, Kennard S, Lilly B. NOTCH3 expression is induced in mural cells through an autoregulatory loop that requires endothelial-expressed JAGGED1. Circ. Res. 2009;104:466–475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noseda M, Fu Y, Niessen K, Wong F, Chang L, McLean G, Karsan A. Smooth muscle α-actin is a direct target of Notch/CSL. Circ. Res. 2006;98:1468–1470. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000229683.81357.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doi H, Iso T, Sato H, Yamazaki M, Matsui H, Tanaka T, Manabe I, Arai M, Nagai R, Kurabayashi M. Jagged1-selective notch signaling induces smooth muscle differentiation via a RBP-Jκ-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28555–28564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin S, Hansson EM, Tikka S, Lanner F, Sahlgren C, Farnebo F, Baumann M, Kalimo H, Lendahl U. Notch signaling regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2008;102:1483–1491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Mouton P, Alamowitch S, Domenga V, Cécillion M, Marechal E, et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature. 1996;383:707–710. doi: 10.1038/383707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang Y, Urs S, Liaw L. Hairy-related transcription factors inhibit Notch-induced smooth muscle α-actin expression by interfering with Notch intracellular domain/CBF-1 complex interaction with the CBF-1-binding site. Circ. Res. 2008;102:661–668. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Limbourg A, Ploom M, Elligsen D, Sörensen I, Ziegelhoeffer T, Gossler A, Drexler H, Limbourg FP. Notch ligand Delta-like is essential for postnatal arteriogenesis. Circ. Res. 2007;100:363–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258174.77370.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawke TJ, Garry DJ. Myogenic satellite cells: physiology to molecular biology. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:534–551. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conboy IM, Rando TA. The regulation of Notch signaling controls satellite cell activation and cell fate determination in postnatal myogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasyutina E, Lenhard DC, Wende H, Erdmann B, Epstein JA, Birchmeier C. RBP-J (Rbpsuh) is essential to maintain muscle progenitor cells and to generate satellite cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:4443–4448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Smythe GM, Rando TA. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science. 2003;302:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1087573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun H, Li L, Vercherat C, Gulbagci NT, Acharjee S, Li J, Chung TK, Thin TH, Taneja R. Stra13 regulates satellite cell activation by antagonizing Notch signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCright B, Gao X, Shen L, Lozier J, Lan Y, Maguire M, Herzlinger D, Weinmaster G, Jiang R, Gridley T. Defects in development of the kidney, heart and eye vasculature in mice homozygous for a hypomorphic Notch2 mutation. Development. 2001;128:491–502. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benedito R, Trindade A, Hirashima M, Henrique D, da Costa LL, Rossant J, Gill PS, Duarte A. Loss of Notch signalling induced by Dll4 causes arterial calibre reduction by increasing endothelial cell response to angiogenic stimuli. BMC Dev. Biol. 2008;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gale NW, Dominguez MG, Noguera I, Pan L, Hughes V, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Adams NC, Lin HC, Holash J, et al. Haploinsufficiency of Delta-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:15949–15954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407290101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xue Y, Gao X, Lindsell CE, Norton CR, Chang B, Hicks C, Gendron-Maguire M, Rand EB, Weinmaster G, Gridley T. Embryonic lethality and vascular defects in mice lacking the Notch ligand Jagged1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:723–730. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer A, Schumacher N, Maier M, Sendtner M, Gessler M. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:901–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.291004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]