Abstract

Lipids are vital components of many biological processes and crucial in the pathogenesis of numerous common diseases, but the specific mechanisms coupling intracellular lipids to biological targets and signalling pathways are not well understood. This is particularly the case for cells burdened with high lipid storage, trafficking and signalling capacity such as adipocytes and macrophages. Here, we discuss the central role of lipid chaperones — the fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) — in lipid-mediated biological processes and systemic metabolic homeostasis through the regulation of diverse lipid signals, and highlight their therapeutic significance. Pharmacological agents that modify FABP function may provide tissue-specific or cell-type-specific control of lipid signalling pathways, inflammatory responses and metabolic regulation, potentially providing a new class of drugs for diseases such as obesity, diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Fatty-acid trafficking in cells is a complex and dynamic process that affects many aspects of cellular function. Fatty acids function both as an energy source and as signals for metabolic regulation, acting through enzymatic and transcriptional networks to modulate gene expression, growth and survival pathways, and inflammatory and metabolic responses1,2. Furthermore, fatty acids, particularly linoleic and arachidonic acids, can be metabolized into a diverse and large family of bio-active lipid mediators called eicosanoids, which may function as pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators3,4. In particular, the cyclopentenone prostaglandins, such as PGA1, PGA2 and PGJ2, have potent anti-inflammatory effects through the inhibition of inflammatory kinase pathways. A critical regulatory component of eicosanoid biosynthesis is at the level of availability of unesterified fatty acids liberated from membrane phospholipids. All of these aspects depend on complex processing, shuttling, availability and removal of lipids to keep a delicate balance between lipid species at the target compartments and to regulate their engagement of signalling targets.

Intracellular lipid chaperones known as fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are a group of molecules that coordinate lipid responses in cells and are also strongly linked to metabolic and inflammatory pathways5–9. FABPs are abundantly expressed 14–15 kDa proteins that reversibly bind hydrophobic ligands, such as saturated and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids, eicosanoids and other lipids, with high affinity8,9. FABPs are found across species, from Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans to mice and humans, demonstrating strong evolutionary conservation. However, little is known about their exact biological functions and mechanisms of action. Studies in cultured cells have suggested potential action of FABPs in fatty-acid import, storage and export as well as cholesterol and phospholipid metabolism5,6. FABPs have also been proposed to sequester and/or distribute ligands to regulate signalling processes and enzyme activities. In the broader context, we view FABPs as lipid chaperones that escort lipids and dictate their biological functions. Recently, through the use of various genetic and chemical models in cells as well as whole animals, the FABPs have been shown to be central to lipid-mediated processes and related metabolic and immune response pathways. Such studies have also highlighted their considerable potential as therapeutic targets for a range of associated disorders, including obesity, diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Family of FABPs

Since the initial discovery of FABPs in 1972 (REF. 10), at least nine members have been identified (TABLE 1). Different members of the FABP family exhibit unique patterns of tissue expression and are expressed most abundantly in tissues involved in active lipid metabolism. The family contains liver (L-), intestinal (I-), heart (H-), adipocyte (A-), epidermal (E-), ileal (Il-), brain (B-), myelin (M-) and testis (T-) FABPs. However, it should be noted that this classification is somewhat misleading, as no FABP is exclusively specific for a given tissue or cell type, and most tissues express several FABP isoforms (see below). The regulation of tissue-specific expression and function of various FABPs is poorly understood. The expression of FABPs in a given cell type seems to reflect its lipid-metabolizing capacity. In hepatocytes, adipocytes and cardiac myocytes, where fatty acids are prominent substrates for lipid biosynthesis, storage or breakdown, the respective FABPs make up between 1% and 5% of all soluble cytosolic proteins5. These amounts can further increase following periods of mass influx of lipids into these cells. Increased fatty-acid exposure leads to a marked increase in FABP expression in most cell types11. Endurance training or pathological nutrient changes, as seen in diabetes for example, can also result in high levels of FABP in skeletal muscle cells12. Similar effects have also been seen in hepatocytes and adipocytes after exposure to chronically elevated extracellular lipid levels11. These observations suggest that there is a built-in adaptive sensing system that responds to the lipid status of the target cells and regulates lipid stochiometry with the FABPs.

Table 1.

Family of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs)

| Gene | Common name | Alternative names | Expression | Chromosomal location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Mus musculus | Rattus norvegicus | ||||

| Fabp1 | Liver FABP | L-FABP | Liver, intestine, pancreas, kidney, lung, stomach | 2p11 | 6 C1 | 4q32 |

| Fabp2 | Intestinal FABP | I-FABP | Intestine, liver | 4q28–q31 | 3 G1 | 2q42 |

| Fabp3 | Heart FABP | H-FABP, MDGl | Heart, skeletal muscle, brain, kidney, lung, stomach, testis, aorta, adrenal gland, mammary gland, placenta, ovary, brown adipose tissue | 1p32–p33 | 4 D2.2 | 5q36 |

| Fabp4 | Adipocyte FABP | A-FABP, aP2 | Adipocyte, macrophage, dendritic cell | 8q21 | 3 A1 | 2q23 |

| Fabp5 | Epidermal FABP | E-FABP, PA-FABP, mal1 | Skin, tongue, adipocyte, macrophage, dendritic cell, mammary gland, brain, intestine, kidney, liver, lung, heart, skeletal muscle, testis, retina, lens, spleen | 8q21.13 | 3 A1–3 | 2 |

| Fabp6 | Ileal FABP | Il-FABP, I-BABP, gastrotropin | Ileum, ovary, adrenal gland, stomach | 5q33.3–q34 | 11 B1.1 | 10q21 |

| Fabp7 | Brain FABP | B-FABP, MRG | Brain, glia cell, retina, mammary gland | 6q22–q23 | 10 B4 | 20q11 |

| Fabp8 | Myelin FABP | M-FABP, PMP2 | Peripheral nervous system, Schwann cell | 8q21.3–q22.1 | 3 A1 | 2q23 |

| Fabp9 | Testis FABP | T-FABP | Testis, salivary gland, mammary gland | 8q21.13 | 3 A2 | 2q23 |

aP2, adipocyte P2; I-BABP, ileal bile acid-binding protein; MDGI, mammary derived growth inhibitor; MRG, MDGI-related gene; PA-FABP, psoriasis-associated FABP; PMP2, peripheral myelin protein 2.

As small intracellular proteins, FABPs appear to access the nucleus under certain conditions, and potentially target fatty acids to transcription factors, such as members of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family — PPAR-α, PPAR-δ and PPAR-γ — in the nuclear lumen. L-FABP, H-FABP, A-FABP and E-FABP themselves are controlled by these transcription factors, which are liganded by fatty acids or other hydrophobic agonists13–15. L-FABP and PPAR-α physically interact, and therefore it has been suggested that L-FABP could be considered a co-activator in PPAR-mediated gene regulation16. In a similar way, E-FABP interacts with PPAR-δ and A-FABP with PPAR-γ15. A recent study has indicated that continuous nucleocytoplasmic shuttling may underlie transcriptional activation of PPAR-γ by A-FABP17. However, in the case of A-FABP, its actions also provided a negative feedback to terminate PPAR-γ action, and the absence of A-FABP resulted in enhanced nuclear hormone receptor activity in the macrophage18. It is unclear whether such a feedback regulation occurs with other isoforms in other cell types and how specificity is achieved in the chaperoning activity towards lipid species.

Ligand affinity and structure of FABPs

All FABPs bind long-chain fatty acids with differences in ligand selectivity, binding affinity and binding mechanism6 as a result of small structural differences between isoforms. In general, the more hydrophobic the ligand the tighter the binding affinity — with the exception of unsaturated fatty acids. It is also possible that the needs of target cells determine the affinity and even selectivity of the major isoform present at different sites. For example, B-FABP is highly selective for very long-chain fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid19. On the other hand, L-FABP exhibits binding capacity for a broad range of ligands from lysophospholipids to haem8.

Several FABP isoforms have been structurally investigated as isolated recombinant proteins by X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance and other biochemical and biophysical techniques. FABPs have an extremely wide range of sequence diversity: from 15% to 70% sequence identity between different members6. However, all known FABPs share almost identical three-dimensional structures (BOX 1). Common to all FABPs is a 10-stranded antiparallel β-barrel structure, which is formed by two orthogonal five-stranded β-sheets6. The binding pocket is located inside the β-barrel, the opening of which is framed on one side by the N-terminal helix-loop-helix ‘cap’ domain, and fatty acids are bound to the interior cavity. There is a conserved three-element fingerprint that provides a signature for all FABPs (PRINTS pattern FATTYACIDBP; PR00178) (BOX 2).

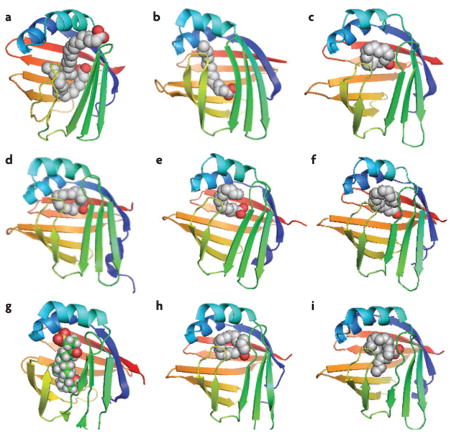

Box 1. Crystal structure of ligand-bound FABPs.

Generally, one or two conserved basic amino-acid side chains are required to bind the carboxylate site of a fatty-acid ligand in the binding pocket of a fatty acid-binding protein (FABP)69. The hydrocarbon tail of the ligand is lined on one side by hydrophobic amino-acid residues and on the other side by ordered water molecules, thus creating the small differences of FABP types in the enthalpic and entropic contributions to ligand binding. Below, the crystal structures of various ligand-bound FABPs are shown (graphics were created using PyMOL).

The binding pocket of liver FABP (L-FABP; FABP1) is considerably larger than that of other FABPs, allowing the binding of two fatty-acid molecules with differing affinities (a). Here, two oleic acids are bound to rat L-FABP (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 1lfo), and show that the fatty acids are bound in opposite orientation with the carboxylate group of the second fatty acid protruding from the cavity and facing the solvent96. In rat intestinal FABP (I-FABP; FABP2), the ligand (palmitic acid) is bound in a slightly bent conformation97 (PDB code: 2ifb) (b). Other members generally bind a fatty acid as a twisted U-shaped entity9,98: a palmitic acid bound to human heart FABP (H-FABP; FABP3) (PDB code: 2hmb) (c); a palmitic acid bound to human adipocyte FABP (A-FABP; FABP4) (PDB code: 2hnx) (d); a palmitic acid bound to human epidermal FABP (E-FABP; FABP5) (PDB code: 1b56) (e); an oleic acid bound to bovine myelin FABP (M-FABP; FABP8) (PDB code: 1pmp) (f). An exception is for human ileal FABP (Il-FABP; FABP6), which binds the bile acid such as taurocholic acid (PDB code: 1o1v) (g). Human brain FABP (B-FABP; FABP7) binds oleic acid in the U-shaped way (PDB code: 1fe3) (h); however, its binding pocket can also accommodate very long-chain docosahexaenoic acid in a helical conformation19 (PDB code: 1fdq) (i).

Box 2. Domain distribution of FABP family members.

There is a conserved fingerprint for all fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) (PRINTS pattern FATTYACIDBP; PR00178), which is derived from three motifs. Motif 1 includes the G-x-W triplet, which forms part of the first β-strand (βA) and corresponds to a similar motif in the sequence of lipocalins, in which it has the same conformation and location within the protein fold99 (see PROSITE pattern FABP; PS00214). Motif 2 spans the C terminus of strand 4 (βD) and includes strand 5 (βE). Motif 3 encodes strands 9 (βI) and 10 (βJ).

In adipocyte FABP (A-FABP; FABP4), potential functional domains include a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and its regulation site, nuclear export signal (NES) and a hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) binding site17,26,100. The primary sequence of A-FABP does not show a readily identifiable NLS. However, the signal could be found in the 3D structure of the protein and was mapped to three basic residues (K21, R30 and K31) located in the helix–loop–helix region, whose side chains shift their orientation upon ligand binding to form a functional NLS17. The NES is also not apparent in the primary sequence, but assembles in the tertiary structure from three nonadjacent leucine residues (L66, L86 and L91) to form a motif reminiscent to that of established NES17. Activation of NLS in A-FABP involves closure of the portal loop, resulting in contraction of the binding pocket. Swinging doorway comprised of F57 perturbs a critical helix containing the NLS26. It has been suggested that activated and non-activated ligand conformations of A-FABP for NLS have different homodimeric configurations. Non-activating ligands (for example, oleate and stearate) protrude from the portal, preventing its closure and preserving the integrity of a homodimeric interface, which masks the NLS, while activating ligands (for example, troglitazone, linoleic acid and anilinonaphthalene sulphonate) favour an alternative homodimer in which the NLS is exposed26.

The representative crystal structure of FABP is human A-FABP (PDB code: 2hnx). The structural and functional domains as well as critical amino-acid residues are marked. The graphic depiction of protein structure was created with PyMOL.

Functions of FABPs

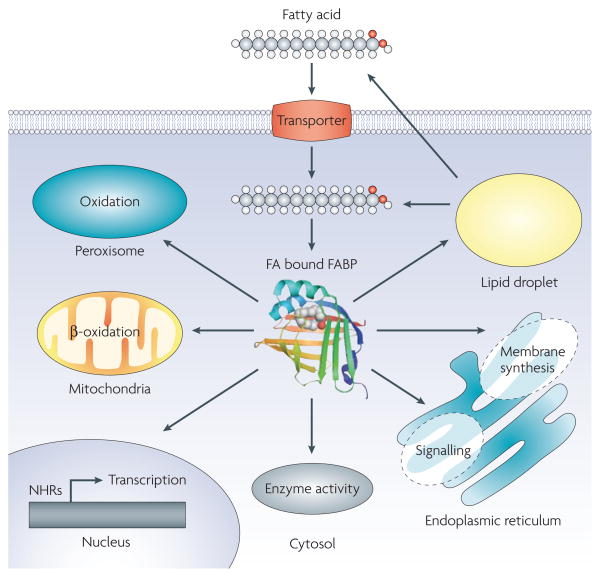

Numerous functions have been proposed for FABPs. As lipid chaperones, FABPs may actively facilitate the transport of lipids to specific compartments in the cell, such as to the lipid droplet for storage; to the endoplasmic reticulum for signalling, trafficking and membrane synthesis; to the mitochondria or peroxisome for oxidation; to cytosolic or other enzymes to regulate their activity; to the nucleus for lipid-mediated transcriptional regulation; or even outside the cell to signal in an autocrine or paracrine manner (FIG. 1). The proper engagement of targets in a spatially controlled manner requires the action of lipid chaperones. Interestingly, the functions of lipid chaperones studied so far relate to detrimental outcomes.

Figure 1. Putative functions of FABP in the cell.

Fatty-acid (FA) trafficking accompanied by the fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) in the cell is shown. As lipid chaperones, FABPs have been proposed to play a role in the transport of lipids to specific compartments in the cell: to lipid droplets for storage; to the endoplasmic reticulum for signalling, trafficking and membrane synthesis; to the mitochondria or peroxisome for oxidation; to cytosolic or other enzymes to regulate their activity; to the nucleus for the control of lipid-mediated transcriptional programs via nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs) or other transcription factors that respond to lipids; or even outside the cell to signal in an autocrine or paracrine manner.

FABP content in most cells is generally proportional to the rates of fatty-acid metabolism11. FABPs are also involved in the conversion of fatty acids to eicosanoid intermediates and in the stabilization of leukotrienes20,21. Furthermore, a direct protein–protein interaction between hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) activity and A-FABP or E-FABP in adipocytes has also been reported22–25. In general, the interacting protein partners for FABPs are poorly understood, and the searches for such proteins with conventional approaches have not been fruitful. Movement of FABPs into the nucleus and interaction with nuclear hormone receptors is possible, and this mechanism might potentially deliver ligands to this protein family15–17,26. Again, little is known regarding this potential action and how lipids regulate subcellular localization of FABPs. Also, how these simple chaper-ones overcome specificity or stoichiometry constraints remains elusive. Clear evidence on the specific impact of FABPs on cell biology and lipid metabolism in complex systems had been lacking until FABP-deficient mice models were created. As discussed below, consequences of genetically altered FABP expression in cells or whole animals dramatically enhanced the understanding of FABP functions (TABLES 2,3), but also raised interesting new questions and possibilities regarding systemic effects of FABPs in vivo and the underlying mechanisms. These studies also opened up novel possibilities to tackle a wide range of metabolic diseases through therapeutic targeting of FABPs, particularly A-FABP, with synthetic ligands.

Table 2.

Knockout and transgenic mouse models for FABPs

| Mouse strain |

Diet | Body weight |

FA uptake |

Serum | Ins. sens. |

Fatty liver |

FABPs* | Notes | Refs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu. | Ins. | FFA | TG | Chol. | |||||||||

| Liver FABP (L-FABP/FABP1) | |||||||||||||

| L-FABP−/− | Regular | → | ↓ | ↓ | → | → | → | Liv: chol. ↑; chol. ester ↑; phospholipid ↑; FA binding ↓ | 28 | ||||

| L-FABP−/− | Regular | → | ↓ | → | ↓‡ | → | → | → | ↓§ | ‡Fed state; §48 hour fasted | 29 | ||

| L-FABP−/− | High fat/chol. | ↑ | ↑ | Female | 30 | ||||||||

| L-FABP−/− | High fat/chol. | ↓ | → | → | → | ↑ | → | → | ↓ | Male | 31 | ||

| L-FABP−/− | High fat‡ | ↓ | → | ↓ | ↓ | → | ↓ | Female; ‡high-saturated fat diet | 32 | ||||

| L-FABP−/− | Regular | E ↑ (Liv) | Female | 32 | |||||||||

| Intestinal FABP (I-FABP/FABP2) | |||||||||||||

| I-FABP−/− | Regular | ↑‡ | → | ↑ | ↑‡ | ↓‡ | → | L, II → (Liv/Int) | ‡Male | 35 | |||

| I-FABP−/− | High fat | ↑‡/↓§ | → | ↑ | ↑‡ | ↓§ | ↑‡/↓§ | ‡Male; §female | 35 | ||||

| Heart FABP (H-FABP/FABP3) | |||||||||||||

| H-FABP−/− | Regular | → | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | → | → | L, A, E, B → (Ht/Mu) | Glu. uptake: Ht ↑, Mu →; exercise intolerance, Ht: hypertrophy | 38 | |||

| H-FABP−/− | High fat | ↓ | ↑ | → | → | 38 | |||||||

| H-FABP−/− | Regular | ↓ | L, A, E, B → (Ht) | Ht: glu. uptake →; glu. oxidation ↑; TG →; glycogen ↑ | 39 | ||||||||

| H-FABP−/− | Regular | ↓ | Mu: glu. oxidation ↑; TG ↓; glycogen ↓ | 40 | |||||||||

| H-FABP−/− | Regular | No regulation: development/function of mammary gland | 45 | ||||||||||

| H-FABPBLG-promoter | Regular | H ↑ (Ma) | No regulation: development/function of mammary gland | 46 | |||||||||

| Epidermal FABP (E-FABP/FABP5) | |||||||||||||

| E-FABP−/− | Regular | → | → | → | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | → | H, A, B → (‡) | Ad‡, testes, tongue, brain | 70 | ||

| E-FABP−/− | High fat | ↓ | ↓ | → | ↑‡ | → | → | ↑ | → | ‡Marginally | 70 | ||

| E-FABP−/− | Regular | H ↑ (Liv) | FA composition → (skin), TEWL: basal ↓; recovery ↓ | 71 | |||||||||

| E-FABP−/−ob/ob | Regular | → | ↓ | ↓‡ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | → | ‡Marginally | 70 | ||

| E-FABPaP2-promoter | Regular | → | → | E ↑ (Ad); A ↓ (Ad) | Basal and stimulated lipolysis ↑; FA composition → (Ad) | 25 | |||||||

| E-FABPaP2-promoter | High fat | → | ↑ | → | → | → | → | ↓ | E ↑ (Ad); A ↓ (Ad) | 70 | |||

| Brain FABP (B-FABP/FABP7) | |||||||||||||

| B-FABP−/− | Regular | L, I, H, A, E → (Br) | Anxiety ↑; fear memory ↑; DHA ↓ (neonate) | 79 | |||||||||

| B-FABP−/− | Regular | Prepulse inhibition ↓; neurogenesis ↓ | 78 | ||||||||||

Type of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are: A, adipocyte; B, brain; E, epidermal; H, heart; I, intestinal; II, ileal; L, liver. Ad, adipose tissue; Br, brain; Chol., cholesterol; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; FA, fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acid; Glu., glucose; Ht, heart; Ins. sens., insulin sensitivity; Liv, liver; Ma, mammary gland; Mu, muscle; TEWL, transepidermal water loss; TG, triglyceride.

Table 3.

Knockout mouse models for A-FABP (FABP4)

| Mouse strain | Diet | Body weight | FA uptake | Serum | Ins. sens. | Fatty liver | Athero. | FABPs* | Notes | Refs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu. | Ins. | FFA | TG | Chol. | ||||||||||

| A-FABP | ||||||||||||||

| A-FABP−/− | Regular | → | → | → | ↑‡ | ↓ | → | → | E ↑ (Ad) | ‡Marginally | 53 | |||

| A-FABP−/− | High fat | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑‡ | ↓ | → | ↑↑ | → | ‡Marginally | 53 | |||

| A-FABP−/− | Regular | Stimulated lipolysis ↓; insulin secretion ↓; HSL level → | 23 | |||||||||||

| A-FABP−/− | Regular | → | E ↑ (Ad) | Stimulated lipolysis ↓; adipose FAs ↑ | 24 | |||||||||

| A-FABP−/− | Regular | Allergic airway inflammation ↓ | 62 | |||||||||||

|

A-FABP−/− ob/ob |

Regular | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑↑ | E ↑ (Ad) | 54 | ||||

|

A-FABP−/− ApoE−/− |

Regular | → | → | → | → | ↑‡ | ↓ | E →(Mφ) | ‡Female | 55 | ||||

|

A-FABP−/− ApoE−/− |

High fat/chol. | ↑ | → | → | → | → | → | ↓ | 63 | |||||

| A-FABP inhibitor (BMS309043) as reference | ||||||||||||||

|

A-FABP+/+ E-FABP+/+ |

High fat | → | ↑ | 90 | ||||||||||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− |

High fat | → | → | 90 | ||||||||||

| ob/ob | Regular | → | ↓ | ↓ | ↑‡ | ↓ | → | ↑ | ↓ | A, E → (Ad) | ‡Marginally | 90 | ||

| ApoE−/− | High fat/chol. | → | → | → | → | → | → | → | ↓ | 90 | ||||

| A-FABP/E-FABP | ||||||||||||||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− |

Regular | ↓ | ↑‡/↓§ | ↓ | → | ↑ | → | → | ↑ | L, I, H, B → (||) | Altered FA composition (||); ‡C12:0; §C18:0; ||Ad, Mu, Liv | 82 | ||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− |

High fat | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | → | → | ↑↑↑ | ↓ | 82 | ||||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− ob/ob |

Regular | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑↑↑ | ↓ | 83 | ||||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− ApoE−/− |

Regular | ↓‡ | → | → | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓↓ | ‡Male | 84 | ||||

|

A-FABP−/− E-FABP−/− ApoE−/− |

Survival ↑ | 84 | ||||||||||||

Type of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are: A, adipocyte; B, brain; E, epidermal; H, heart; I, intestinal. Ad, adipose tissue; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; Athero., atherosclerosis; C12:0, lauric acid; C18:0, stearic acid; Chol., cholesterol; E-FABP, epidermal FABP (also known as FABP5); FA, fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acid; Glu., glucose; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; Ins. sens., insulin sensitivity; Liv, liver; Mφ, macrophage; Mu, muscle; TG, triglyceride.

Liver FABP

L-FABP, also known as FABP1, is abundant in the liver cytoplasm, but is also expressed in several other sites, including the intestine, pancreas, kidney, lung and stomach6. L-FABP in the liver can represent as much as 5% of all cytosolic proteins in hepatocytes5. The promoter of the L-FABP gene contains a peroxisome-proliferator response element, and accordingly the mRNA levels are increased by fatty acids, dicarboxylic acids and retinoic acid8. Unlike the other members of the FABP family, L-FABP is able to bind two ligands simultaneously via two different binding sites with high and low affinities27. Peroxisome proliferators always bind L-FABP with low affinity, whereas the strength of the binding with fatty acids depends on which affinity site is utilized. This property of L-FABP is suggested to serve as a feature enabling ligand delivery through interactions with target receptors. In addition to binding fatty acids, such as oleic acid, L-FABP can carry acyl-coenzyme A, eicosanoids, lysophospholipids, carcinogens, anticoagulants, such as warfarin, and haem, making it probably the most versatile chaperone in terms of its ligand repertoire8.

Surprisingly, no change in appearance, gross morphology or viability was observed in L-FABP-deficient mice28,29. These mice were of normal weight, and despite a modest reduction in fatty-acid uptake, serum levels of triacylglycerols and fatty acids were unchanged28,29. However, metabolic parameters in mice upon exposure to high-fat/cholesterol diet differed between studies30–32 (TABLE 2). This fragility in the phenotype points to the critical importance of the dietary exposures, gender and subtle differences in genetic background or lipid composition in the biology of L-FABP. It is also possible that the principal action of L-FABP lies elsewhere, for example in the kidney or intestine. Interestingly, recent studies have suggested that fatty acid-induced expression of L-FABP occurs in the proximal tubules and showed that urinary L-FABP in humans may be a useful clinical marker that can help predict and monitor the progression of renal diseases33.

Intestinal FABP

I-FABP, also known as FABP2, is expressed in the epithelium of the small intestine. In the small intestine, three members of FABPs are present, namely L-FABP, I-FABP and Il-FABP (also known as FABP6), although they are distributed in different segments34. L-FABP is mostly expressed in the proximal region, whereas Il-FABP is restricted to the distal part of the small intestine. I-FABP is expressed throughout the intestine, but most abundantly in the distal segment. It is difficult to assess the individual contributions of these proteins to lipid absorption and metabolism at the sites at which they are present, and more work is needed in this regard.

I-FABP-deficient mice were viable and fertile35. Fat absorption was not affected by the loss of I-FABP, and compensation by L-FABP or Il-FABP was not observed35. Both genders of mice with I-FABP-deficiency exhibited elevated plasma levels of insulin, but normal levels of glucose. Male I-FABP−/− mice gained more weight, had larger livers and had significantly higher triglyceride levels regardless of diet. By contrast, female I-FABP−/− mice gained less weight, had smaller livers on a high-fat diet and exhibited no difference in plasma triglyceride levels. Although the mechanisms responsible for these gender differences remain unclear, it appears that fatty-acid uptake can be mediated by the remaining FABPs, possibly L-FABP and Il-FABP, without the need for increased total amounts of FABPs to compensate for the lack of I-FABP.

It has been reported that a polymorphism in I-FABP, an alanine to threonine substitution at codon 54 (Thr54), was associated with insulin resistance and decreased lipid oxidation in Pima Indians, a population with an extremely high prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes36. However, the association between the Thr54 allele and insulin resistance in various other populations has been modest and sometimes controversial5,6. Again, this indicates the need to examine these genetic variations in large populations, and, more importantly, in the context of dietary and other environmental exposures.

Heart FABP

H-FABP, also known as FABP3, has been isolated from a wide range of tissues, including heart, skeletal muscle, brain, renal cortex, lung, testis, aorta, adrenal gland, mammary gland, placenta, ovary and brown adipose tissue6,12. The level of H-FABP was influenced by exercise, PPAR-α agonists and testosterone, and oscillates with circadian rhythm8,14,37. In muscle cells, H-FABP was involved in the uptake of fatty acids and their subsequent transport towards the mitochondrial β-oxidation system. Increased fatty-acid exposure in vitro and in vivo resulted in elevated H-FABP expression11,12. Conditions with elevated plasma lipids may result in increased H-FABP levels in myocytes, as seen in endurance training11,12.

Studies in H-FABP-deficient mice showed that the uptake of fatty acids was severely inhibited in the heart and skeletal muscle, whereas plasma concentrations of free fatty acids were increased38. Cardiac and skeletal muscle metabolism is reported to switch from fatty-acid oxidation towards glucose oxidation when there is an inability to obtain sufficient amounts of fatty acids39,40. Consequently, H-FABP-deficient mice were rapidly fatigued and exhausted by exercise, showing a reduced tolerance to physical activity. Localized cardiac hypertrophy was also observed in the older animals38.

The mammary gland prominently expresses H-FABP in the course of cell differentiation and formation of ductal structures during lactation41. In the mammary gland, mammary-derived growth inhibitor (MDGI) was identified as a growth regulator, which later turned out to be a mixture of H-FABP and A-FABP, and the amino-acid sequence of MDGI reveals 95% similarity to H-FABP42,43. It has been shown that H-FABP inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells44. However, this growth inhibition appeared to be unrelated to the ligand-binding capacity of the FABPs. On the other hand, studies involving overexpression and ablation of H-FABP demonstrated that H-FABP did not play a role in regulating the development or function of the mammary gland45,46. Thus, the biological function of H-FABP in the mammary gland remains unclear and somewhat controversial. Similarly, little is known about the effect of lack of H-FABP in tissues other than the heart or mammary gland.

H-FABP is abundant in the myocardium and rapidly released from cardiomyocytes into the circulation after the onset of cell damage. Serum concentration of H-FABP has been proposed as an early biochemical marker of acute myocardial infarction and a sensitive marker for the detection and evaluation of myocardial damage in patients with heart failure47,48. However, the concentration of H-FABP is significantly influenced by renal clearance and thus has limitations in its usefulness for patients with renal dysfunction49. The concentration of other FABPs has also been proposed as a biomarker for the detection of tissue injury: B-FABP for brain injury and I-FABP for intestinal damage50. The utility of these potential biomarkers remains to be explored.

Adipocyte FABP

A-FABP, also known as FABP4, was first detected in mature adipocytes and adipose tissue51,52. This protein has also been termed adipocyte P2 (aP2) because of its high sequence similarity (67%) to peripheral myelin protein 2 (M-FABP/FABP8)52. Expression of A-FABP is highly regulated during differentiation of adipocytes, and its mRNA is transcriptionally controlled by fatty acids, PPAR-γ agonists and insulin5,7.

A-FABP is the best-characterized isoform among the entire FABP family with the most striking biology (FIG. 2). A-FABP-deficient mice exhibited reduced hyperinsulin-aemia and insulin resistance in the context of both dietary and genetic obesity, but the effect of A-FABP on insulin sensitivity was not observed in lean mice53,54. In adipocytes, the loss of A-FABP was compensated by overexpression of E-FABP (FABP5/mal1), which is present in the normal adipocyte only in extremely small amounts. The adipocytes obtained from A-FABP-deficient mice have reduced efficiency of lipolysis in vitro and in vivo22–24. This was initially attributed to the ability of A-FABP to bind and activate HSL, although the definitive links between HSL activation and A-FABP have not yet been established in vivo. It also remains to be seen whether this potential mechanism can account for the alterations in lipolysis in A-FABP-deficiency.

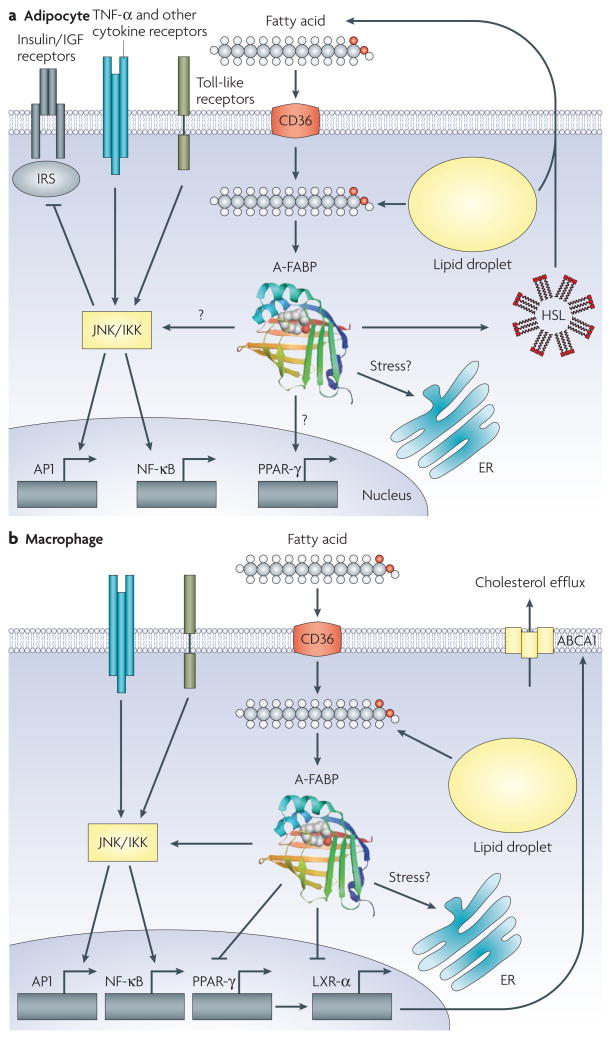

Figure 2. Functions of A-FABP in the adipocyte and macrophage.

a. Other than general functions of the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP), adipocyte FABP (A-FABP; FABP4) interacts with hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) to potentially modulate its catalytic activity and integrates several signalling networks that control inflammatory responses potentially through JNK/inhibitor of kappa kinase (IKK) and insulin action in the adipocyte. In addition to regulating fatty-acid influx, A-FABP is also important in controlling adipocyte lipid hormone production to regulate distant targets. The transcriptional events resulting from these actions are not fully understood. b. In the macrophage, A-FABP regulates inflammatory responses via the IKK-nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway and attenuates cholesterol efflux through inhibition of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ)-liver X receptor-α (LXR-α)-ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) pathway. In both macrophages and adipocytes, A-FABP has a critical role in integrating lipid signals to organelle responses, particularly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). AP1, adaptor protein 1; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Recent studies have demonstrated A-FABP expression in macrophages upon their differentiation from monocytes, and following activation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, lipopolysaccharide, PPAR-γ agonists and oxidized low-density lipoprotein55–59. In addition, it has been reported that A-FABP is also expressed in the dendritic cells60. Interestingly, expression of A-FABP in macrophages was suppressed by a cholesterol-lowering statin in vitro61. Notably, adipocytes express much higher levels of A-FABP than macrophages (approximately 10,000-fold)62. In macrophages, A-FABP modulated inflammatory responses and cholesterol ester accumulation55, and total A-FABP deficiency conferred dramatic protection against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient mice with or without the additional challenge of high-cholesterol-contained Western diets55,63. Bone-marrow transplantation studies demonstrated that this atheroprotective effect of A-FABP is predominantly, if not entirely, related to its actions in the macrophage55. These results demonstrate a central role for A-FABP in the development of major components of the metabolic syndrome through its distinct actions in adipocytes and macrophages, and its ability to integrate metabolic and inflammatory responses.

In human and mouse monocyte cell lines, A-FABP expression became evident in differentiated or activated macrophages55–59. The 5.4 kilobase A-FABP promoter/enhancer, which is known to direct A-FABP expression in the adipocytes, was sufficient to induce the expression in macrophages as tested in three independent transgenic lines55. Interestingly, E-FABP was also present in macrophages and regulated in an essentially identical manner. Unlike the compensatory regulation in adipocytes, E-FABP did not appear to be significantly upregulated in macrophages derived from A-FABP−/− mice (termed A-FABP−/− macrophages)55. It has been suggested that A-FABP is a critical regulator of the PPAR-γ–liver X receptor-α (LXR-α)–ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) pathway and contributes to foam-cell formation in macrophages18. PPAR-γ activity was elevated in A-FABP−/− macrophages with stimulation of downstream targets including LXR-α and ABCA1, resulting in enhanced efflux of cholesterol18. In parallel, A-FABP coordinates the inflammatory activity of macrophages. In A-FABP−/− macrophages, several inflammatory signalling responses were suppressed, including production of cytokines such as tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL1β), IL6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1). Moreover, production and function of pro-inflammatory enzymes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) were also suppressed18. It has also been demonstrated that A-FABP deficiency results in reduction in the activity of the inhibitor of kappa kinase (IKK)-nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, which may, at least in part, underlie the alterations in cytokine expression18. Consequently, the overall reduction in foam-cell formation and modified inflammatory responses of A-FABP−/− macrophages was highly beneficial against the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in mouse models.

A recent study showed that A-FABP was also expressed in human bronchial epithelial cells under highly specific conditions. The induction of A-FABP was only responsive to T helper 2 (TH2) cytokines, IL4 and IL13, which are crucial to the development of asthma, whereas the TH1 cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) resulted in a moderate suppression of A-FABP62. It is worth noting that the level of A-FABP expression in bronchial epithelial cells was significantly lower when compared with adipocytes and macrophages, even after stimulation. Interestingly, PPAR-γ agonists were unable to induce A-FABP expression in bronchial epithelial cells, and transcriptional regulation was mediated, at least in part, by signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) activity62. Interestingly, a striking protection from airway inflammation was detected in A-FABP-deficient mice, indicating possible protection against asthma62. In this setting, there was no detectable contribution of bone-marrow-derived elements in the airway phenotype associated with FABP-deficiency. Additionally, A-FABP expression was detected in lipoblasts in lipoblastoma and liposarcoma, but not in other benign adipose tissue or malignant connective tissue or epithelial tumours64. A-FABP expression has also been linked to human urothelial carcinomas65. The significance of these associations remains to be determined.

Notably, recent studies conducted in our laboratory and by others showed that A-FABP was released from adipocytes and abundantly present in human serum. In addition, the concentration of A-FABP may be associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases66–68 (G. Tuncman and G.S.H., unpublished observations). However, the biological function of A-FABP in the serum remains an unaddressed question of great importance. If the secreted form of A-FABP or any other FABP is biologically active, this might introduce a paradigm shift in the understanding of regulated lipid chaperoning and the networking of local lipid-mediated processes with systemic metabolic responses.

Epidermal FABP

E-FABP, also known as FABP5, psoriasis-associated FABP (PA-FABP) or mal1, is expressed most abundantly in epidermal cells of the skin. It is also present in other tissues, including the tongue, adipose tissue (adipocyte and macrophage), dendritic cell, mammary gland, brain, kidney, liver, lung and testis6,7,60. As all these tissues express additional members of the FABP family, the exact function of E-FABP is especially difficult to elucidate.

The ratio of A-FABP to E-FABP in adipocytes isolated from normal mice was approximately 99:1 (REF. 69). Although E-FABP is the minor fraction in adipocytes, the stochiometry of A-FABP and E-FABP appears to be approximately 1:1 in the macrophage under physiological conditions55. These two proteins have 52% amino-acid similarity and bind various fatty acids and synthetic compounds with similar selectivity and affinity5. Interestingly, E-FABP expression was dramatically increased in adipocytes, but not in macrophages, derived from A-FABP−/− mice53,55. The mechanism underlying this striking molecular compensation is not known.

Transgenic mice overexpressing the E-FABP gene in adipose tissue exhibited a minor phenotype with enhanced basal and hormone-stimulated lipolysis25. When fed a high-fat diet, adipose tissue-specific E-FABP overexpression in transgenic mice resulted in a reduction in systemic insulin sensitivity70. By contrast, absence of E-FABP in these mice led to a modest increase in insulin sensitivity70. The adipocytes in E-FABP−/− mice showed an increased capacity for insulin-dependent glucose transport. Other than increased H-FABP in liver71, no compensatory increase was observed in the expression of H-FABP, A-FABP or B-FABP in adipose tissue, testis, tongue or brain in E-FABP-deficient mice70.

Complete or partial lack of E-FABP in the liver during perinatal development was compensated by an overexpression of H-FABP71. Otherwise, there were no apparent changes in morphology and histology in the liver of E-FABP−/− mice, and this model appeared remarkably healthy71. The loss of E-FABP in the epidermis did not alter the fatty-acid composition of the epidermal membrane, where fatty acids are essential components of the water permeability barrier of the skin71. There was only a minor reduction in transepidermal water loss in E-FABP-deficient mice as the water permeability barrier recovered more slowly following acetone-induced damage71.

Interestingly, a study has shown that overexpression of E-FABP in a benign, non-metastatic rat mammary epithelial cell line may induce metastasis72. Hence, E-FABP seems to have the opposite effects to those reported for H-FABP (MDGI) and B-FABP (MRG), which inhibit tumour growth. E-FABP was also reported to influence survival pathways by activation of retinoic acid through PPAR-δ73. Taken together, there are interesting possibilities in linking FABP function to tumorigenesis, which remain largely unexplored. In addition, E-FABP is expressed in astrocytes and glia of the prenatal and perinatal brain, and, unlike B-FABP, also in neurons74. E-FABP expression was induced following peripheral nerve injury, suggesting a role in the regeneration of neurons5.

Brain FABP

B-FABP, also known as FABP7, is expressed in various regions of the mouse brain in the mid-term embryonic stage, but the expression decreases as differentiation progresses75. The protein is strongly expressed in radial glia cells of the developing brain, especially in the preperinatal stage, but only weakly in mature glia of the white matter. Neurons of the grey matter express H-FABP and E-FABP but not B-FABP. B-FABP is distinguished from other FABPs by its strong affinity for n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, in particular, docosa-hexaenoic acid. As this very long-chain fatty acid is an important nutrient for the nervous system, it has been considered a natural ligand for B-FABP76.

Pathologically, B-FABP was overexpressed in patients with Down’s syndrome77 and schizophrenia78. Recently, B-FABP-deficient mice were shown to be viable with no macroscopic abnormalities79. Interestingly, B-FABP-deficient mice exhibited altered emotional behavioural responses, decreased prepulse inhibition that is a typical behaviour in schizophrenia, and attenuated neurogenesis in vivo78,79. It has also been suggested that B-FABP influences the correct migration of developing neurons into cortical layers75. Moreover, similar to H-FABP42,43, B-FABP is prominently expressed in the mammary gland, and its overexpression inhibited tumour growth in a mouse breast cancer model80,81.

Lipid chaperones and metabolic diseases

As described above, adipocyte/macrophage FABPs, A-FABP and E-FABP, have a central role in many aspects of metabolic diseases including obesity, diabetes and atherosclerosis. The only cells that co-express A-FABP and E-FABP are adipocytes and macrophages. However, the dramatic compensation by E-FABP in adipocytes derived from A-FABP−/− mice had masked the effects of A-FABP-deficiency on overall metabolic health53,70. To remove all FABP activity from these cells and address the metabolic impact of these FABP isoforms, mice with combined deficiency of A-FABP and E-FABP (A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/−) were also generated. The A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/− mice fed on a high-fat diet or in the context of severe genetic obesity exhibited alterations in tissue fatty-acid composition and did not develop insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes or fatty liver disease, demonstrating that the protective phenotype of this model far exceeds that of individual FABP-deficiency models82,83. Similarly, when intercrossed into the ApoE−/− model, A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/− mice developed dramatically less atherosclerosis compared with A-FABP-deficient or wild-type mice of the same background84. Remarkably, A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/−ApoE−/− animals also had significantly increased survival when fed a Western-type hypercholesterolaemic diet, which is probably due to increased plaque stability and significant overall metabolic health84. It will be interesting to test whether this increase in survival could be extrapolated into increased longevity in this model.

A-FABP−/−, E-FABP−/− or A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/− mice have one notable feature associated with obesity: a minor but significant elevation of plasma fatty acids53,54,70,82,83. In general, increased fatty acids are positively correlated with the development of obesity and insulin resistance, but paradoxically, adipocyte/macrophage FABP-deficient mouse models were more insulin sensitive. This observation challenges the current dogma in the mechanistic basis of fatty-acid action in the metabolic syndrome, and indicates that the distribution and availability of intracellular fatty acids (and derivatives), rather than the absolute amounts, may be more critical in pathological conditions. More detailed lipid profiling showed increased shorter-chain (C14) fatty acids and decreased longer-chain (C18 or C20) fatty acids in the muscle and adipose tissues of A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/− mice. These changes favoured enhanced insulin receptor signalling, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, and fatty-acid oxidation82. There were also alterations in liver fatty-acid composition, which differed from other sites and favoured lipid mobilization over storage and suppressed stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase (SCD) and sterol-regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) activities, thus reducing hepatosteosis82. The A-FABP−/−E-FABP−/− mouse model has shed new light on the role of FABPs in regulating intracellular fatty-acid profiles and how these alterations are linked to specific biochemical pathways important in metabolic homeostasis.

It has recently been suggested that macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue is a feature of adipose tissue inflammatory responses triggered by obesity and hence may contribute to the metabolic consequences such as insulin resistance85,86. Although the impact of A-FABP on atherosclerosis was essentially exclusive to its actions in the macrophage55, studies in cell-based experiments and bone-marrow transplantation using adipocyte/macrophage FABP-deficiency models showed that FABP action in both adipocytes and macrophages contribute to the inflammatory and metabolic responses in vitro and in vivo101. However, the impact of adipocyte FABP is again greater than the impact of bone-marrow-derived cells on systemic insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in vivo101.

Therapeutic targeting of FABPs

Adipocyte/macrophage FABPs, A-FABP and E-FABP act at the interface of metabolic and inflammatory pathways. These FABPs exert a dramatic impact on obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis and asthma. The creation of pharmacological agents to modify FABP function may therefore provide tissue-specific or cell-type-specific control of lipid signalling pathways, inflammatory responses and metabolic regulation, thus offering a new class of multi-indication therapeutic agents.

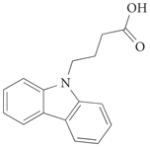

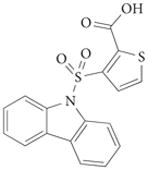

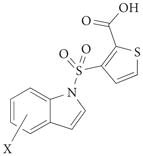

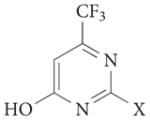

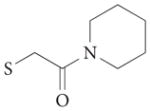

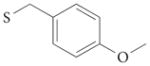

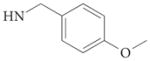

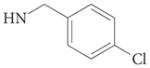

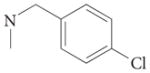

Recently, a small series of A-FABP inhibitors have been identified (TABLE 4). These include carbazole-based (compounds 1 and 2) and indole-based (compounds 3a–c) inhibitors87; benzylamino-6-(trifluoromethyl) pyrimidin-4(1H) inhibitors (compounds 4a–f)88; and a biphenyl azole inhibitor (compound 5; also known as BMS309403)89. In a fluorescent 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulphonic acid binding displacement assay, BMS309403 had Ki values <2 nM for A-FABP compared with 250 nM for H-FABP and 350 nM for E-FABP89. By contrast, the endogenous fatty acids, palmitic acid and oleic acid, had A-FABP Ki values of 336 nM and 185 nM, respectively89. BMS309403 seems to have greater potency compared with the other reported potential inhibitors, which have IC50 values >0.5 μM87–89.

Table 4.

Series of A-FABP inhibitors in development

| Structure | Compound name | X group | IC50 (μM)* | PDB code | Refs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-FABP | H-FAPB | E-FABP | I-FABP | |||||

|

1 | – | 0.57 | <0.6 | 6.7 | >100 | 1tow | 87 |

|

2 | – | 1.1 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 42 | – | 87 |

|

3a | 3-Me | 1.5 | – | – | – | – | 87 |

| 3b | 6-Me | 1.3 | – | – | – | – | 87 | |

| 3c | 5-Br | 1.3 | 9.8 | 14 | 3.9 | – | 87 | |

|

4a |  |

1 | – | – | – | 1tou | 88 |

| 4b |  |

0.6 | 17 | – | – | – | 88 | |

| 4c |  |

3.9 | >100 | – | – | – | 88 | |

| 4d |  |

2.9 | >100 | – | – | – | 88 | |

| 4e |  |

4.0 | >100 | – | – | – | 88 | |

| 4f |  |

24 | >100 | – | – | – | 88 | |

|

5 (BMS309403) | – | <2* | 250* | 350* | – | 2nnq | 89,90 |

For compound 5, values are for K, (nM). A-FABP, adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (FABP4); E-FABP, epidermal FABP (FABP5); H-FABP, heart FABP (FABP3); I-FABP, intestinal FABP (FABP2).

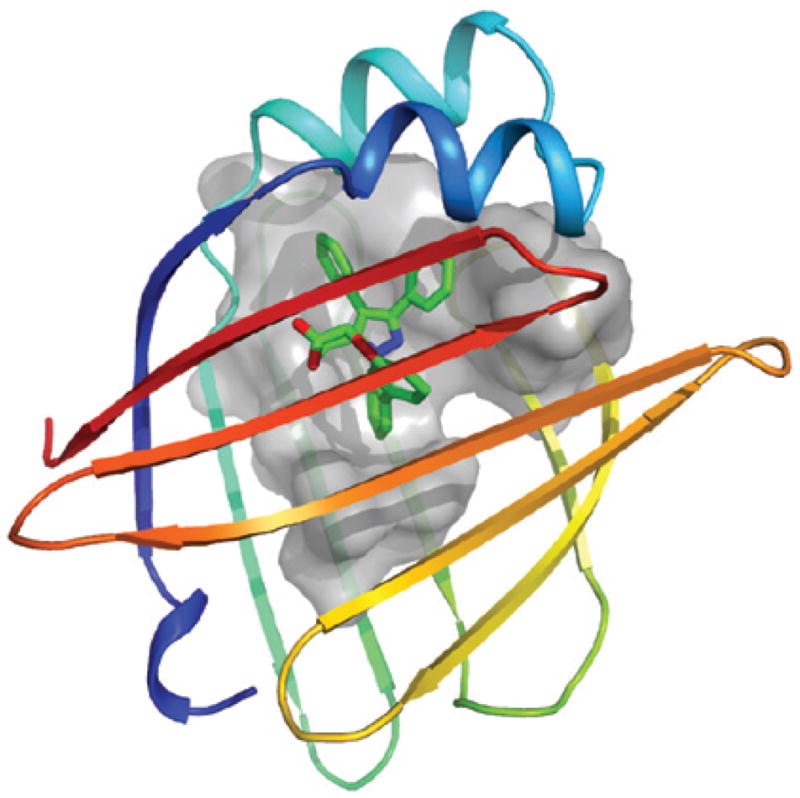

In a recent study, we reported the development of an isoform-specific and biologically active synthetic A-FABP inhibitor, and demonstrated that chemical inhibition of A-FABP could be a potential therapeutic strategy against insulin resistance, diabetes, fatty liver disease as well as atherosclerosis in independent experimental models90. The orally active small-molecule BMS309403, a rationally designed, potent and selective inhibitor of A-FABP, interacts with the fatty-acid binding pocket within the interior of A-FABP to inhibit binding of endogenous fatty acids (FIG. 3). Results of X-ray crystallography studies identified the specific interactions of BMS309403 with key residues, such as Ser53, Arg106, Arg126 and Tyr128, within the fatty-acid binding pocket as the basis of its high in vitro binding affinity and selectivity for A-FABP over other FABPs89. In particular, Ser53, which is a Thr in H-FABP and E-FABP, is proximal to the ethyl substituent of the pyrazole ring and might act as a critical residue to influence ligand interactions.

Figure 3. Crystal structure of the synthetic A-FABP inhibitor BMS309403 bound to human A-FABP.

Human fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) crystallized in complex with BMS309403, a synthetic adipocyte FABP (A-FABP; FABP4) inhibitor, is shown (PDB code: 2nnq). The molecule occupies the internal binding pocket of A-FABP. One side of the internal surface of the binding pocket is shown as a grey colour where the designed surface interaction with the synthetic inhibitor takes place. The figure was created using PyMOL and provided by R. Parker, Bristol–Myers Squibb.

BMS309403 markedly reduced the extent of atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE−/− mice90. Cell-based studies revealed reduced macrophage foam-cell formation with decreased cholesterol-ester accumulation, increased cholesterol efflux and decreased production of several inflammatory mediators by this inhibitor in a target-specific manner. BMS309403 did not produce these effects in cells lacking A-FABP. Inhibition of A-FABP improved glucose metabolism and enhanced insulin sensitivity in both dietary and genetic mouse models of obesity and diabetes90. Furthermore, fatty liver infiltration and the expression of obesity-associated inflammatory mediators were also suppressed in the insulin resistant and obese ob/ob mouse model. The activity of JNK1, which is crucial in the generation of inflammatory responses and inhibition of insulin action in obesity91,92, was also attenuated together with improved insulin action in both adipose and liver tissues upon A-FABP inhibition90.

Previous studies suggest that the expression, regulation and metabolic function of human A-FABP may be similar to that of mice5,53,55. In fact, a genetic variant was identified within the promoter region of the human A-FABP gene (T-87C), which altered C/EBP binding and significantly reduced the transcriptional activity of the human A-FABP promoter, resulting in diminished A-FABP expression in adipose tissue of carriers with this allele93. In a large population sampling, individuals with the A-FABP variant had lower triglyceride levels, had reduced cardiovascular disease risk, and were protected from obesity-induced type 2 diabetes93. This study provided a critical proof of principle that the biological functions of A-FABP may be similar between mice and humans. Definitive genetic links will require additional large-scale population studies to determine whether this applies to different cohorts. Further studies are also needed to determine whether FABP inhibitors could be safely used in humans and show efficacy against metabolic diseases. If successful, inhibition of A-FABP in humans may become a promising new class of therapeutics against a broad range of metabolic diseases including obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis and possibly other inflammatory conditions such as asthma.

Concluding remarks

FABP-mediated lipid metabolism is closely linked to both metabolic and inflammatory processes through modulating critical lipid-sensitive pathways in target cells, especially adipocytes and macrophages. Mice under normal physiological conditions did not have a compromised phenotype when adipocyte/macrophage FABPs were deleted, but they benefited enormously when faced with systemic pathological stresses, particularly of metabolic and inflammatory origin. The phenotypes observed in the absence of adipocyte/macrophage FABPs illustrate the integrating role in metabolic and inflammatory responses, and suggest that these genes may represent an example of the “thrifty” gene hypothesis94. Evolutionary selection has clearly preserved the function of FABPs in that they are present in invertebrates (lower eukaryotes) up to vertebrates, including humans95. It may be that the close link between the inflammatory and metabolic responses underlie this conservation. The adipocyte/macrophage FABPs may be necessary to fine-tune the balance between the availability of metabolic resources and the control of inflammatory responses. That is, when humans faced feast or famine and when under pressure with pathogens, the presence of FABPs may have been beneficial by ensuring a strong macrophage immune response or by maintaining adipose tissue energy stores as part of the “thrifty” phenotype to survive. Under the unnaturally excessive and continuous caloric intake, decreased energy expenditure, prolonged lifespan and the distinctly stressful lifestyle of contemporary humans, FABPs may not be sufficient to maintain inflammatory or metabolic homeostasis, and hence no longer be beneficial. In this scenario, their presence now facilitates the formation of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, atherosclerosis and inappropriate immune responses. In such conditions, targeting the adipocyte/macrophage FABPs, particularly A-FABP, offers highly attractive therapeutic opportunities for a broad range of pathologies in metabolic diseases by addressing an evolutionary bottleneck in the metabolic design of humans. In addition to the well-studied and characterized isoforms, FABPs in general may also offer targeting opportunities for the development of therapeutic or preventive agents for other diseases. For example, H-FABP and B-FABP may be targeted in tumours where they are heavily and aberrantly expressed, and regulate growth and survival responses. Much work is still needed in mouse models to illustrate the precise applications and indications for other isoforms. Moreover, as well as targeting these molecules directly, the ability of FABPs to modulate lipid signalling and trafficking in a tissue-specific or restricted manner could also be exploited for controlling the activity of their targets such as nuclear hormone receptors in select cell types and tissues. Development of high affinity and selective chemicals to target A-FABP provides a critical proof of principle that this class of proteins are suitable for drug development. Future studies should also increase the repertoire of synthetic ligands for the additional members of the FABP family as their biological functions become better understood.

Acknowledgments

Studies on FABPs and related areas in the Hotamisligil laboratory are supported by the National Institutes of Health, USA, and the American Diabetes Association. M.F. has been supported by fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the American Diabetes Association. We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions made by past and current laboratory members and long-standing collaborations, particularly with M. Linton and R. Parker. We also regret the inadvertent omission of many important references owing to space limitations.

Footnotes

DATABASES

OMIM:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM

Down's syndrome | obesity | type 2 diabetes | schizophrenia

UniProtKB:http://ca.expasy.org/sprot

FABP1 | FABP2 | FABP3 | FABP4 | FABP5 | FABP6 | FABP7

FURTHER INFORMATION

PRINTS:

http://www.bioinf.manchester.ac.uk/dbbrowser/PRINTS/

PROSITE:http://expasy.org/prosite/

Protein Data Bank (PDB):

References

- 1.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414:799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1671–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haunerland NH, Spener F. Fatty acid-binding proteins — insights from genetic manipulations. Prog Lipid Res. 2004;43:328–349. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chmurzynska A. The multigene family of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs): function, structure and polymorphism. J Appl Genet. 2006;47:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makowski L, Hotamisligil GS. The role of fatty acid binding proteins in metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:543–548. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000180166.08196.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coe NR, Bernlohr DA. Physiological properties and functions of intracellular fatty acid-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1391:287–306. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman AW, Veerkamp JH. New insights into the structure and function of fatty acid-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1096–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ockner RK, Manning JA, Poppenhausen RB, Ho WK. A binding protein for fatty acids in cytosol of intestinal mucosa, liver, myocardium, and other tissues. Science. 1972;177:56–58. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4043.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veerkamp JH, van Moerkerk HT. Fatty acid-binding protein and its relation to fatty acid oxidation. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;123:101–106. doi: 10.1007/BF01076480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanotti G. Muscle fatty acid-binding protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1441:94–105. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schachtrup C, Emmler T, Bleck B, Sandqvist A, Spener F. Functional analysis of peroxisome-proliferator-responsive element motifs in genes of fatty acid-binding proteins. Biochem J. 2004;382:239–245. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motojima K. Differential effects of PPARα activators on induction of ectopic expression of tissue-specific fatty acid binding protein genes in the mouse liver. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(00)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan NS, et al. Selective cooperation between fatty acid binding proteins and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in regulating transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5114–5127. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5114-5127.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfrum C, Borrmann CM, Borchers T, Spener F. Fatty acids and hypolipidemic drugs regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α- and γ-mediated gene expression via liver fatty acid binding protein: a signaling path to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2323–2328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051619898. This excellent manuscript describes a potential and interesting mechanism for the action of L-FABP as a regulator of specific gene-expression programs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayers SD, Nedrow KL, Gillilan RE, Noy N. Continuous nucleocytoplasmic shuttling underlies transcriptional activation of PPARγ by FABP4. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6744–6752. doi: 10.1021/bi700047a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makowski L, Brittingham KC, Reynolds JM, Suttles J, Hotamisligil GS. The fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, coordinates macrophage cholesterol trafficking and inflammatory activity. Macrophage expression of aP2 impacts peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and IκB kinase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12888–12895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balendiran GK, et al. Crystal structure and thermodynamic analysis of human brain fatty acid-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27045–27054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ek BA, Cistola DP, Hamilton JA, Kaduce TL, Spector AA. Fatty acid binding proteins reduce 15-lipoxygenase-induced oxygenation of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1346:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmer JS, Dyckes DF, Bernlohr DA, Murphy RC. Fatty acid binding proteins stabilize leukotriene A4: competition with arachidonic acid but not other lipoxygenase products. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2138–2144. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400240-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen WJ, Sridhar K, Bernlohr DA, Kraemer FB. Interaction of rat hormone-sensitive lipase with adipocyte lipid-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5528–5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5528. In this study, the authors demonstrate an interaction between HSL and A-FABP and suggest that this interaction might serve to deliver a lipid ligand to a catalytic site and regulate the enzymatic activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheja L, et al. Altered insulin secretion associated with reduced lipolytic efficiency in aP2−/− mice. Diabetes. 1999;48:1987–1994. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coe NR, Simpson MA, Bernlohr DA. Targeted disruption of the adipocyte lipid-binding protein (aP2 protein) gene impairs fat cell lipolysis and increases cellular fatty acid levels. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hertzel AV, Bennaars-Eiden A, Bernlohr DA. Increased lipolysis in transgenic animals overexpressing the epithelial fatty acid binding protein in adipose cells. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:2105–2111. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200227-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillian RE, Ayers SD, Noy N. Structural basis for activation of fatty acid-binding protein 4. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1246–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rolf B, et al. Analysis of the ligand binding properties of recombinant bovine liver-type fatty acid binding protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1259:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin GG, et al. Decreased liver fatty acid binding capacity and altered liver lipid distribution in mice lacking the liver fatty acid-binding protein gene. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21429–21438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newberry EP, et al. Decreased hepatic triglyceride accumulation and altered fatty acid uptake in mice with deletion of the liver fatty acid-binding protein gene. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51664–51672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin GG, et al. Liver fatty acid binding protein gene ablation potentiates hepatic cholesterol accumulation in cholesterol-fed female mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G36–G48. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00510.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newberry EP, Xie Y, Kennedy SM, Luo J, Davidson NO. Protection against Western diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis in liver fatty acid-binding protein knockout mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:1191–1205. doi: 10.1002/hep.21369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newberry EP, et al. Diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis in L-Fabp−/− mice is abrogated with SF, but not PUFA, feeding and attenuated after cholesterol supplementation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G307–G314. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00377.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamijo-Ikemori A, Sugaya T, Kimura K. Urinary fatty acid binding protein in renal disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;374:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agellon LB, Toth MJ, Thomson AB. Intracellular lipid binding proteins of the small intestine. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vassileva G, Huwyler L, Poirier K, Agellon LB, Toth MJ. The intestinal fatty acid binding protein is not essential for dietary fat absorption in mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:2040–2046. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0959com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bar LJ, et al. An amino acid substitution in the human intestinal fatty acid binding protein is associated with increased fatty acid binding, increased fat oxidation, and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1281–1287. doi: 10.1172/JCI117778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuhashi M, et al. Fenofibrate improves insulin sensitivity in connection with intramuscular lipid content, muscle fatty acid-binding protein, and β-oxidation in skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:321–329. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Binas B, Danneberg H, McWhir J, Mullins L, Clark AJ. Requirement for the heart-type fatty acid binding protein in cardiac fatty acid utilization. FASEB J. 1999;13:805–812. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaap FG, Binas B, Danneberg H, van der Vusse GJ, Glatz JF. Impaired long-chain fatty acid utilization by cardiac myocytes isolated from mice lacking the heart-type fatty acid binding protein gene. Circ Res. 1999;85:329–337. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binas B, et al. A null mutation in H-FABP only partially inhibits skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E481–E489. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00060.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binas B, et al. Hormonal induction of functional differentiation and mammary-derived growth inhibitor expression in cultured mouse mammary gland explants. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1992;28A:625–634. doi: 10.1007/BF02631038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohmer FD, et al. Identification of a polypeptide growth inhibitor from bovine mammary gland. Sequence homology to fatty acid- and retinoid-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:15137–15143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Specht B, et al. Mammary derived growth inhibitor is not a distinct protein but a mix of heart-type and adipocyte-type fatty acid-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19943–19949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huynh HT, Larsson C, Narod S, Pollak M. Tumor suppressor activity of the gene encoding mammary-derived growth inhibitor. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2225–2231. In this study, the authors identified a biochemical entity, which turned out to be an FABP, as a regulator of growth. This paper is critical, despite many disagreements, in raising the possibility that FABPs could exit the cells and regulate other cells, an idea that has not been sufficiently appreciated. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark AJ, Neil C, Gusterson B, McWhir J, Binas B. Deletion of the gene encoding H-FABP/MDGI has no overt effects in the mammary gland. Transgenic Res. 2000;9:439–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1026552629493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Binas B, Gusterson B, Wallace R, Clark AJ. Epithelial proliferation and differentiation in the mammary gland do not correlate with cFABP gene expression during early pregnancy. Dev Genet. 1995;17:167–175. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka T, Hirota Y, Sohmiya K, Nishimura S, Kawamura K. Serum and urinary human heart fatty acid-binding protein in acute myocardial infarction. Clin Biochem. 1991;24:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(91)90571-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setsuta K, et al. Use of cytosolic and myofibril markers in the detection of ongoing myocardial damage in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2002;113:717–722. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furuhashi M, et al. Serum ratio of heart-type fatty acid-binding protein to myoglobin. A novel marker of cardiac damage and volume overload in hemodialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;93:C69–C74. doi: 10.1159/000068520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelsers MM, Hermens WT, Glatz JF. Fatty acid-binding proteins as plasma markers of tissue injury. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;352:15–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiegelman BM, Frank M, Green H. Molecular cloning of mRNA from 3T3 adipocytes. Regulation of mRNA content for glycerophosphate dehydrogenase and other differentiation-dependent proteins during adipocyte development. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:10083–10089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt CR, Ro JH, Dobson DE, Min HY, Spiegelman BM. Adipocyte P2 gene: developmental expression and homology of 5′-flanking sequences among fat cell-specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3786–3790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hotamisligil GS, et al. Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science. 1996;274:1377–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1377. This is a crucial paper describing the first loss-of-function model of any FABP family members, and demonstrating a role for A-FABP in metabolic homeostasis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uysal KT, Scheja L, Wiesbrock SM, Bonner-Weir S, Hot Hotamisligil GS. Improved glucose and lipid metabolism in genetically obese mice lacking aP2. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3388–3396. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Makowski L, et al. Lack of macrophage fatty-acid-binding protein aP2 protects mice deficient in apolipoprotein E against atherosclerosis. Nature Med. 2001;7:699–705. doi: 10.1038/89076. An important study describing the presence and function of A-FABP in the macrophages, which has not been recognized for a long time, and the central importance of macrophage A-FABP in atherosclerosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelton PD, Zhou L, Demarest KT, Burris TP. PPARγ activation induces the expression of the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein gene in human monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:456–458. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu Y, Luo N, Lopes-Virella MF. Oxidized LDL induces the expression of ALBP/aP2 mRNA and protein in human THP-1 macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:2017–2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu Y, Luo N, Lopes-Virella MF, Garvey WT. The adipocyte lipid binding protein (ALBP/aP2) gene facilitates foam cell formation in human THP-1 macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kazemi MR, McDonald CM, Shigenaga JK, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein expression and lipid accumulation are increased during activation of murine macrophages by toll-like receptor agonists. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1220–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159163.52632.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rolph MS, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell function and T cell priming by the fatty acid-binding protein AP2. J Immunol. 2006;177:7794–7801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Llaverias G, et al. Atorvastatin reduces CD68, FABP4, and HBP expression in oxLDL-treated human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shum BO, et al. The adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein aP2 is required in allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2183–2192. doi: 10.1172/JCI24767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boord JB, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, alters late atherosclerotic lesion formation in severe hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1686–1691. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000033090.81345.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bennett JH, Shousha S, Puddle B, Athanasou NA. Immunohistochemical identification of tumours of adipocytic differentiation using an antibody to aP2 protein. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:950–954. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.10.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohlsson G, Moreira JM, Gromov P, Sauter G, Celis JE. Loss of expression of the adipocyte-type fatty acid-binding protein (A-FABP) is associated with progression of human urothelial carcinomas. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:570–581. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500017-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu A, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein is a plasma biomarker closely associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Clin Chem. 2006;52:405–413. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tso AW, et al. Serum adipocyte fatty acid binding protein as a new biomarker predicting the development of type 2 diabetes: a 10-year prospective study in a Chinese cohort. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2667–2272. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yeung DC, et al. Serum adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein levels were independently associated with carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1796–1802. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.146274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simpson MA, LiCata VJ, Ribarik Coe N, Bernlohr DA. Biochemical and biophysical analysis of the intracellular lipid binding proteins of adipocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;192:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maeda K, et al. Role of the fatty acid binding protein mal1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2003;52:300–307. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Owada Y, Suzuki I, Noda T, Kondo H. Analysis on the phenotype of E-FABP-gene knockout mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jing C, et al. Human cutaneous fatty acid-binding protein induces metastasis by up-regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor gene in rat Rama 37 model cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4357–4364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schug TT, Berry DC, Shaw NS, Travis SN, Noy N. Opposing effects of retinoic acid on cell growth result from alternate activation of two different nuclear receptor. Cell. 2007;129:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.050. This excellent study demonstrates the impact of E-FABP in regulating survival responses to retinoic acid through interactions with a nuclear hormone receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Veerkamp JH, Zimmerman AW. Fatty acid-binding proteins of nervous tissue. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16:133–142. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:133. discussion 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feng L, Hatten ME, Heintz N. Brain lipid-binding protein (BLBP): a novel signaling system in the developing mammalian CNS. Neuron. 1994;12:895–908. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu LZ, Sanchez R, Sali A, Heintz N. Ligand specificity of brain lipid-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24711–24719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sanchez-Font MF, Bosch-Comas A, Gonzalez-Duarte R, Marfany G. Overexpression of FABP7 in Down syndrome fetal brains is associated with PKNOX1 gene-dosage imbalance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2769–2777. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Watanabe A, et al. Fabp7 maps to a quantitative trait locus for a schizophrenia endophenotype. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:2469–2483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Owada Y, et al. Altered emotional behavioral responses in mice lacking brain-type fatty acid-binding protein gene. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:175–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shi YE, et al. Antitumor activity of the novel human breast cancer growth inhibitor, mammary-derived growth inhibitor-related gene, MRG. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3084–3091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hohoff C, Spener F. Correspondence re: Y. E. Shi et al., Antitumor activity of the novel human breast cancer growth inhibitor, mammary-derived growth inhibitor-related gene, MRG. Cancer Res 57, 3084–3091, 1997. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4015–4017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maeda K, et al. Adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid binding proteins control integrated metabolic responses in obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2005;1:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cao H, et al. Regulation of metabolic responses by adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid-binding proteins in leptin-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:1915–1922. doi: 10.2337/db05-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Boord JB, et al. Combined adipocyte-macrophage fatty acid-binding protein deficiency improves metabolism, atherosclerosis, and survival in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;110:1492–1498. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141735.13202.B6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu H, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]