Abstract

Fluorophosphonate (FP) head groups were tethered to a variety of chromophores (C) via a triazole group and tested as FPC inhibitors of recombinant mouse (rMoAChE) and electric eel (EEAChE) acetylcholinesterase. The inhibitors showed bimolecular inhibition constants (ki) ranging from 0.3 × 105 M−1min−1 to 10.4 × 105 M−1min−1. When tested against rMoAChE, the dansyl FPC was 12.5-fold more potent than the corresponding inhibitor bearing a Texas Red as chromophore, whereas the Lissamine and dabsyl chromophores led to better anti-EEAChE inhibitors. Most inhibitors were equal or better inhibitors of rMoAChE than EEAChE. 3-Azidopropyl fluorophosphonate, which served as one of the FP head groups, showed excellent inhibitory potency against both AChE’s (1 × 107 M−1min−1) indicating, in general, that addition of the chromophore reduced the overall anti-AChE activity. Covalent attachment of the dabsyl-FPC analog to rMoAChE was demonstrated using size exclusion chromatography and spectroscopic analysis, and visualized using molecular modeling.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), the enzyme responsible for hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) contains three key motifs: an active-site (A-site), a peripheral anionic site (P-site) and a long narrow hydrophobic gorge connecting the A- and P-sites.1 The A-site contains a catalytically reactive serine located 20 Å from the protein surface.2–4 The P-site is located at the protein perimeter and transiently attracts cation substrates prior to translocation to the A-site.5 The gorge is lined with hydrophobic residues to facilitate passage of substrate and other molecules. The A-site is the principal target for non-covalent inhibitors such as tacrine and acridine, and covalent modifiers such as organophosphates, carbamates and sulfonyl halides.6–11

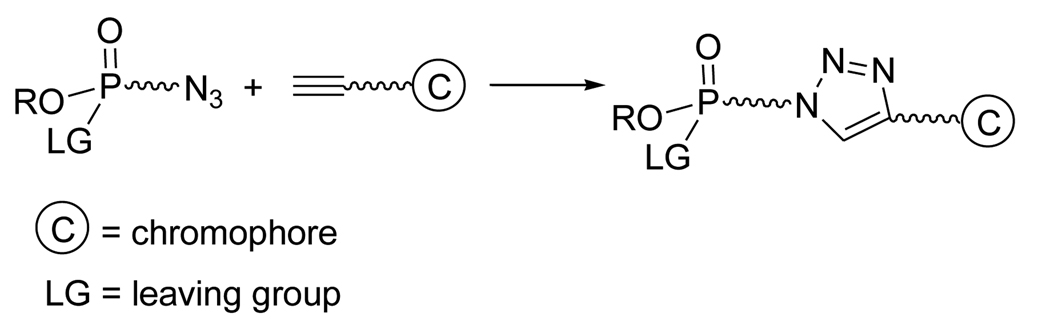

The primary objective of this study was to select and evaluate AChE inhibitors (Fig. 1) that anchor chromophores (C) in the gorge but near to the protein surface. Such structures could serve as reporter groups for protein structure changes without interrupting the favorable ACh to P-site interaction or as visualization tools in proteomics. To seat and locate the proper chromophore probe, a reactive phosphonate group bearing a fluorine as leaving group (LG) was used to attach the molecule to the active site serine (Fig. 1). To more precisely place chromophore groups in the gorge just below the P-site entrance, a panel of chromophore-linked OPs that vary in the chromophore structure were designed with an interatomic distance of slightly less than 20 Å. Owing to slight differences in the chromophore attachment and size, structures were prepared with three- and four-carbon bond linker groups (one methylene spacer variance) to maintain net interatomic distances less than or equal to 20 Å. Chromophores were linked via a triazole to reactive OP groups using click chemistry12 (Fig 1).13–15

Figure 1.

Proposed design for chromophore-linked OPs using click reaction.

Variation in the chromophore group is important because differences in size and chemical properties can play a role in protein binding. For example, the propargyl amide of Lissamine has an IC50 of 50 nM with recombinant mouse AChE whereas other chromophore amides are poor inhibitors.16 In this study, chromophore-linked reactive phosphonates were synthesized, inhibition of two AChE’s determined, the contribution of the chromophore assessed, and an optimized inhibitor used to covalently modify AChE.

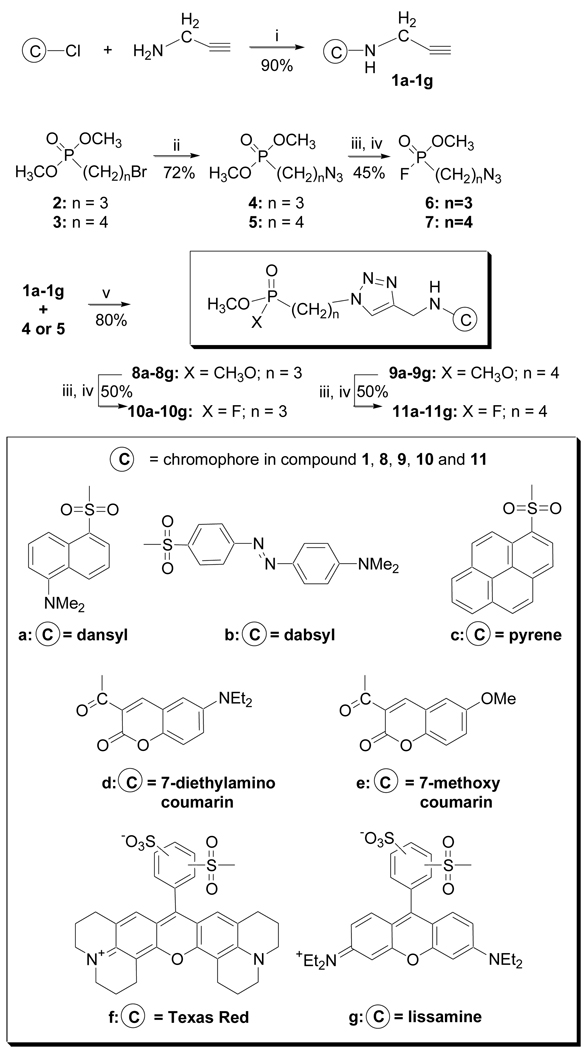

The fluorophosphonate chromophore (FP-C) structures were prepared as shown (Scheme 1). Seven amine-reactive chromophores (sulfonyl-Cl or activated carboxylic ester/NHS) were reacted with propargyl amine to afford the propargyl amides 1a–1g.17 O,O-Dimethyl-(3-bromo propyl)phosphonate 318 and O,O-dimethyl-(4-bromo butyl)phosphonate 4 were converted to the azo-linked OPs 4 and 5. Chromophore-linked phosphonates 8a–g/9a–g were prepared in excellent yield from alkynes (1a–1g) and azides (4/5) using Cu(I) catalysis.12 Phosphonates 8a–g/9a–g were converted to the reactive fluorophosphonate products (10a–g/11a–g;FPCs) via formation of the phosphorus monoacid followed by reaction with cyanuric fluoride (C3N3F3).19,20 Conversion to the P-F bond was monitored by 31P NMR. The phosphorus diesters P(OCH3)2, (~ 34 ppm) shift 3 ppm upfield as the monoacid (~ 31 ppm). Following conversion with cyanuric fluoride, the product shows characteristic P-F coupling constant (JP-F = 1072 Hz).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of a propyl- and butyl-tethered, chromophore-linked fluorophosphonates: (i) TEA, CH2Cl2 (ii) NaN3, CH3CN/H2O (iii) NaOH, 50–60 °C; H+ (iv) C3N3F3, CH2Cl2 (v) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, t-BuOH/H2O. All compounds were fully characterized.

The syntheses of control compounds, azopropyl-and azobutyl-linked FPs 6 and 7, were also conducted to assess the anti-AChE activity of the reactive phosphonate without a chromophore. The same hydrolysis and fluorination reactions were applied to 4 and 5 to afford FPs 6 and 7.

Chromophore-linked FPs 6,7, 10a–g and 11a–g were evaluated as irreversible inhibitors. Rate constants (ki) were determined in a concentration-dependent manner21 using 1/[i] = (Δt/Δlnγ)ki − (1/KD) for all compounds except the Texas Red-FPs (10f and 11f) and lissamine-based FPs (10g/11g). Five inhibitor concentrations causing a range of 20% to 90% inhibition were used along with a control to determine ki and the resulting linear plot (1/[i] ~ Δt/Δlnv) was used in cases when R2 > 0.98 (n≥3). For the Texas Red-linked FPs (10f and 11f) and lissamine-based FPs (10g/11g) less than 50% inhibition was obtained. As a result of this poor inhibition, the resultant plots afforded R2 ≥ 0.80 and other estimated ki(s) ≤ 104 M−1min−1 were obtained.

Paraoxon (EtO)2P(O)OPhNO2 was used as a reference inhibitor with a ki of 4.0×105 M−1min−1 for rMAChE22, 23 and 3.0×105 M−1min−1 for EEAChE24, which are in excellent agreement with literature values.

The ki values for the control compounds 6 and 7 were approximately 106–107 M−1min−1 or 10 to 100-fold stronger than paraoxon. The propyl analog 6 was 10-fold more potent inhibitor than 7 toward both AChE’s.

The twelve chromophore-linked FPs (10a–10g and 11a–11g) were all found to be good inhibitors of both rMAChE and EEAChE and comparable to paraoxon except 11c. The dansyl- and dabsyl-linked FPs, 10a and 10b, were the most potent inhibitors in the series and slightly better inhibitors than paraoxon. The chromophore-linked FPs were all weaker inhibitors (smaller ki) than the control compounds 6/7 indicating that the anchored chromophores reduced inhibition. For the dansyl-, dabsyl, methoxy- and diethylamino coumarin linked FPs, the propyl-linked analogs (10a, 10b, 10d and 10e) were more potent than the corresponding butyl-linked (11a, 11b, 11d and 11e). The ki values for 10/11a, 10/11b, 10/11d and 10/11e suggest that the smaller-sized chromophores likely access the protein and modify the active site with either 3- or 4-carbon linker length. However, the relatively poor ki values for FP-Cs 10/11f indicates that the sterically demanding chromophores may exceed the P-site portal and hinder entry such that the reactive P-F moiety cannot reach/covalently modify the A-site. As such, the kinetic data does not represent an irreversible inhibitor. Recently, we reported that lissamine propargyl amide 1g is a reversible inhibitor of AChE and acting by an independent mechanism.16

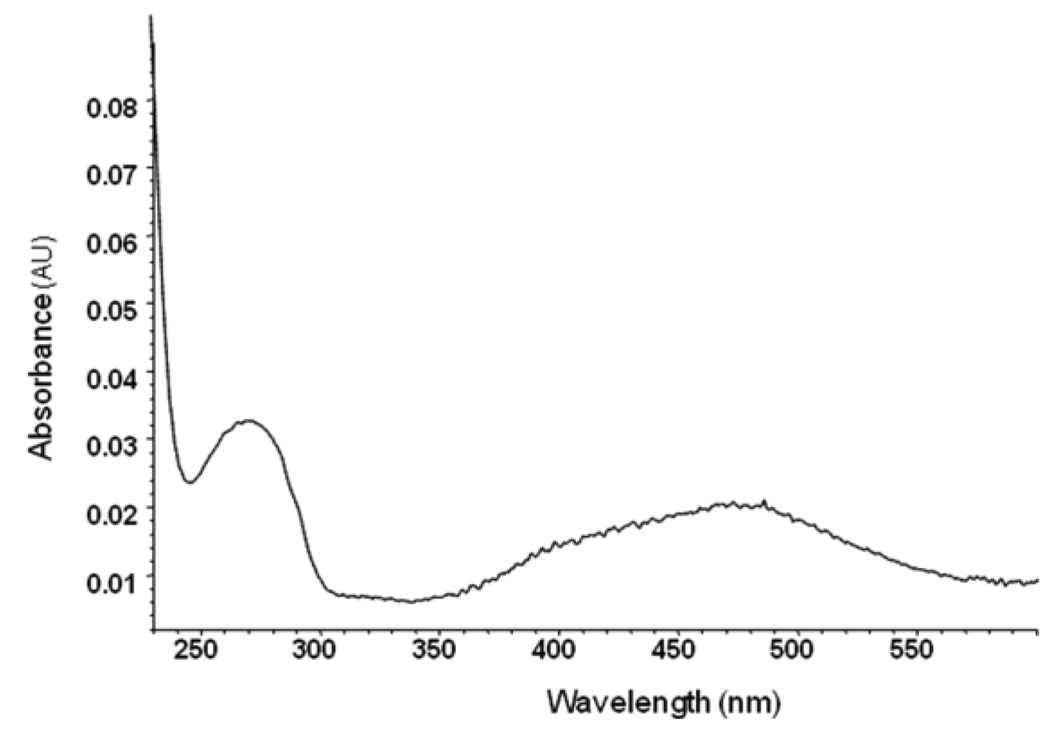

To demonstrate that select chromophore-linked FPs became covalently attached to the enzyme and result in a chromophore-labeled enzyme, dabsyl-linked FP 10b was reacted with rMAChE until complete inhibition. Excess inhibitor was removed from the phosphonylated enzyme using a Spin-OUT Micro Column and the protein fractions were analyzed by UV-Vis. The dabsylated rMAChE solution showed two absorbance maxima at 280 nm and 475 nm accounting for the aromatic side chains rMAChE and the dabsyl moiety, respectively. The molar extinction coefficient for the enzyme-FP-dabsyl complex was 3.1×104 M−1cm−1 in 0.1 M PBS 7.6 at 475 nm, which was determined from the absorption spectrum of the dabsyl-linked FP under the same conditions. The molar extinction coefficient for the enzyme was experimentally derived and calculated by protparam in ExPASy25 as 9.8 × 104 104 M−1cm−1 and 10.0×104 M−1cm−1, respectively. The amount of enzyme-bound inhibitor was calculated from the absorption at 475 nm and corrected for the absorption caused by inhibitor and then determined from the absorption at 280 nm (Fig 2). An estimate of enzyme concentration from its absorption spectrum results in a dabsyl-FP to enzyme stoichiometry of 1.45–1.55 (+/− 0.2). Analysis of the FP-dabsyl enzyme complex by MALDI did not reveal modification of sites in addition to the active site serine.

Figure 2.

UV-Vis of rMAChE inhibited by dabsyl-FP 10b.

To visualize the position and possible interactions between FP-C ligands and AChE, molecular modeling was conducted. Dansyl- 10a, dabsyl- 10b, and the ortho- and para-Texas Red-linked FP 10f were virtually docked into rMAChE using the software GOLD26 and standard settings. A single monomer of rMAChE extracted from the crystal structure (1maa)2 was employed. The top-ranked orientations of dansyl-FP 10a and dabsyl-FP 10b scored significantly higher in the GOLDSCORE best ranking list compared to either Texas Red-linked FP 10f (Table 2).

Table 2.

GOLDSCORE fitness scores of the top-ranked individuals for virtual docking simulations of dansyl- 10a, dabsyl- 10b, and Texas red-linked FP 10f to rMAChE.

| Compound | Chromophore | Fitness |

|---|---|---|

| 10a | Dansyl | 80.14 |

| 10b | Dabsyl | 77.08 |

| 10f | Texas Red, ortho | 8.47 |

| 10f | Texas Red, para | −9.24 |

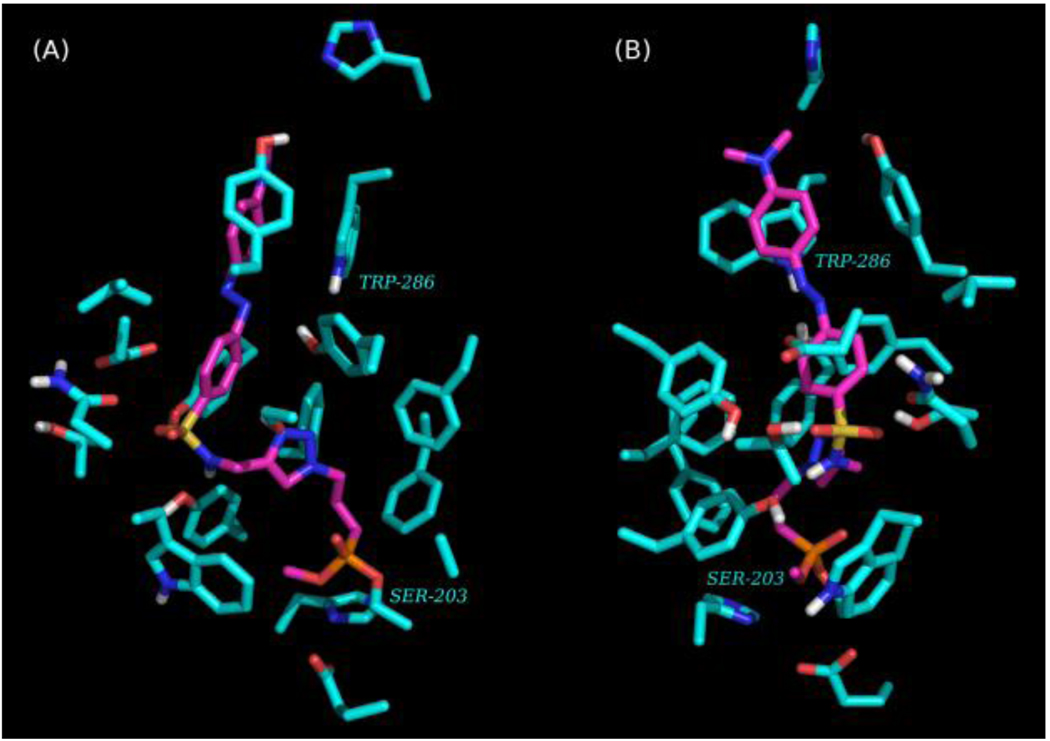

Qualitatively, the top-ranked pose for the dabsyl-linked FP 10b placed the reactive phosphoryl group of this ligand in a better distance and orientation to serine 203 than the dansyl-linked FP 10a. The top-ranked pose for dabsyl-linked FP 10b was merged with the structure of rMAChE, a covalent bond was created between the phosphate group and serine 203, and the energy of the merged structure was minimized using AMBERFF07 forcefield and Tripos Sybyl (St. Louis. MO). The energy minimized merge structure was then subjected to a 10,000×1 fs step molecular dynamics simulation using AMBERFF07 at 300K. After 1,000 steps, the structure with the lowest potential energy was again energy minimized as above. The orientation of dabsyl-linked FP 10b in rMAChE places the chromophore near aromatic residues (e.g., Trp 286; Fig. 3) lining the upper gorge region near the P-site.

Figure 3.

Visualizations of AChE (turquoise) inhibited by dabsyl-FP (magenta) showing a phosphonylated enzyme bound at Ser-203. The chromophore is positioned near P-site residues (e.g., Trp-286). Only residues that are 4Å from dabsyl-FP and polar hydrogens shown. Views A and B are rotated 90 degrees about the vertical axis.

Spontaneous and oxime-induced reactivation27–29 of rMAChE inhibited by 10b was conducted to show that the serine hydroxyl group was covalently modified. Only inhibition at the serine hydroxyl would afford a functional enzyme upon reactivation. To assess spontaneous reactivation, rMAChE was inhibited by 10b to > 90% of its original activity and the inhibition mixture subsequently diluted 50-fold with buffer to halt further inhibition. The enzyme activity was monitored over 2 h, however, no spontaneous reactivation was observed. To assess oxime-induced reactivation, 2-pyridine aldoxime methiodide (2-PAM) was added after the dilution step and showed that rMAChE recovered 30–40% of the original activity in 2 h. When 2-PAM is applied at >1 mM and incubated with inhibited enzyme for 0.5 h, the amount of reactivation was proportional to the reactivator concentration. Thus, rMAChE undergoes covalent modification by 10b and moreover, that the reaction occurs at the active site serine.

In sum, a series of chromophore-linked FP compounds were prepared as potent inhibitors against AChE showing that rMAChE is more reactive than EEAChE. The anti-AChE kinetics revealed that the chromophore, linker and the molecule length collectively affect the ligand binding to the protein. The irreversible inhibition of rMAChE was confirmed by the spectroscopic analysis and the inactivated enzyme can be recovered to 30–40% by 2-PAM. Molecular modeling was used to illustrate that small chromophore-linked FPs fit the active gorge of AChE and the chromophore is positioned near the gorge entrance at the P-site, which can be used to explore the protein structural features and functionalities. FPs containing large chromophores such as Texas Red and lissamine, showed different kinetics than the other FPs, which is likely caused by their larger size or charge attraction to the P-site.

Table 1.

Inhibition rates constants (ki) for 6,7, 10a–10g and 11a–11g against rMAChE and EEAChE.

| Compound |

ki (M−1min−1)a rMAChE |

ki (M−1min−1)a EEAChE |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1.3 ± 0.1 × 107 | 7.7 ± 0.1 × 106 |

| 7 | 1.0 ± 0.1 × 106 | 0.96 ± 0.08 × 106 |

| 10a | 1.0 ± 0.1 × 106 | 1.3 ± 0.1 × 105 |

| 11a | 1.9 ± 0.5 × 105 | 6.2 ± 0.1 × 104 |

| 10b | 7.5 ± 1.0 × 105 | 3.0 ± 0.3 × 105 |

| 11b | 6.5 ± 1.1 × 104 | 1.1 ± 0.1 × 105 |

| 10c | 4.0 ± 0.6 × 105 | 1.8 ± 0.3 × 105 |

| 11c | ND | ND |

| 10d | 2.1 ± 0.7 × 105 | 2.5 ± 0.4 × 105 |

| 11d | 1.4 ± 0.2 × 105 | 3.3 ± 0.8 × 104 |

| 10e | 6.5 ± 0.6 × 105 | 1.8 ± 0.1 × 104 |

| 11e | 3.5 ± 0.6 × 104 | 2.7 ± 1.0 × 104 |

| 10f | ~ 1 × 104 | ~ 1 × 104 |

| 11f | ~ 1 × 104 | ~ 1 × 104 |

| 10g | ~ 1 × 104 | ~ 1 × 104 |

| 11g | ~ 1 × 104 | ~ 1 × 104 |

| paraoxon | 4.0 × 105 | 3.0 × 105 |

All ki values (means ± SEM) were determined from ≥ 3 different experiments. ND = not determined, poor solubility.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH UO1-ES016102 (CMT), NIH R43 ES016392 (ATERIS) and NIH U44 NS058229 (ATERIS). Support from the Core Laboratory for Neuromolecular Production (NIH P30-NS055022), Center for Structural and Functional Neuroscience (NIH P20-RR015583) and Molecular Computational Core Facility is appreciated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Koellner G, Kryger G, Millard CB, Silman I, Sussman JL, Steiner T. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne Y, Taylor P, Bougis PE, Marchot P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne Y, Taylor P, Marchot P. Cell. 1995;83:503. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I. Science. 1991;253:872. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barak D, Kronman C, Ordentlich A, Ariel N, Bromberg A, Marcus D, Lazar A, Velan B, Shafferman A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolezal V, Lisa V, Tucek S. Brain Res. 1997;769:219. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00711-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuto TR. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;87:245. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9087245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchot P, Bourne Y, Prowse CN, Bougis PE, Taylor P. Toxicon. 1998;36:1613. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn DM. Chem Rev. 1987;87:955. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolognesi ML, Minarini A, Rosini M, Tumiatti V, Melchiorre C. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:960. doi: 10.2174/138955708785740652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz-Torrero D. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2433. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manetsch R, Krasinski A, Radic Z, Raushel J, Taylor P, Sharpless KB, Kolb HC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12809. doi: 10.1021/ja046382g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krasinski A, Radic Z, Manetsch R, Raushel J, Taylor P, Sharpless KB, Kolb HC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6686. doi: 10.1021/ja043031t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis WG, Green LG, Grynszpan F, Radic Z, Carlier PR, Taylor P, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:1053. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<1053::aid-anie1053>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo L, Suarez AI, Thompson CM. J Enz Inh Med Chem. 2009 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolletta F, Fabbri D, Lombardo M, Prodi L, Trombini C, Zaccheroni N. Organometallics. 1996;15:2415. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maguire AR, Plunkett SJ, Papot S, Clynes M, O'Connor R, Touhey S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:745. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kokotos G, Noula C. J Org Chem. 1996;61:6994. doi: 10.1021/jo9520699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saltmarsh JR, Boyd AE, Rodriguez OP, Radic Z, Taylor P, Thompson CM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:1523. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Featherstone RM. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amitai G, Moorad D, Adani R, Doctor BP. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:293. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kardos SA, Sultatos LG. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:118. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzsprung P, Weil L, Quentin KE. Z. Wass. Abwass. Forsch. 1989;22:67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdonk ML, Cole JC, Hartshorn MJ, Murray CW, Taylor RD. Proteins. 2003;52:609. doi: 10.1002/prot.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langenberg JP, De Jong LP, Otto MF, Benschop HP. Arch Toxicol. 1988;62:305. doi: 10.1007/BF00332492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieske CN, Clark JH, Meyer HG, Lowe JR. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1980;13:205. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassa J, Kuca K, Karasova J, Musilek K. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:1134. doi: 10.2174/138955708785909871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]