Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the association of efavirenz hypersusceptibility (EFV-HS) with clinical outcome in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of EFV plus indinavir (EFV+IDV) vs. EFV+IDV plus abacavir (ABC) in 283 nucleoside-experienced HIV-infected patients.

Methods and Results

Rates of virologic failure were similar in the 2 arms at week 16 (p=0.509). Treatment discontinuations were more common in the ABC arm (p=0.001). Using logistic regression, there was no association between virologic failure and either baseline ABC resistance or regimen sensitivity score. Using 3 different genotypic scoring systems, EFV-HS was significantly associated with reduced virologic failure at week 16, independent of treatment assignment. In some patients on the nucleoside-sparing arm, the nucleoside-resistant mutant L74V was selected for in combination with the uncommonly occurring EFV-resistant mutant K103N+L100I; L74V was not detected as a minority variant, using clonal sequence analysis, when the nucleoside-sparing regimen was initiated.

Conclusions

Premature treatment discontinuations in the ABC arm and the presence of EFV-hypersusceptible HIV variants in this patient population likely made it difficult to detect a benefit of adding ABC to EFV+IDV. In addition, L74V, when combined with K103N+L100I, may confer a selective advantage to the virus that is independent of its effects on nucleoside resistance.

Keywords: efavirenz hypersusceptibility, HIV drug resistance, NNRTI resistance, nucleoside resistance

Introduction

Patients who have failed prior combination antiretroviral regimens have lower virologic response rates to combination antiretroviral therapy compared to patients with limited treatment experience 1-11, in part due to the presence of HIV variants with resistance to one or more drugs in the antiretroviral regimen 12. Testing to detect the presence of drug-resistant HIV improves treatment responses in antiretroviral-experienced patients 13, 14, and has become a standard of care to guide selection of salvage regimens 15, 16.

The presence of HIV-1 with hypersusceptibility to antiretroviral drugs may also impact treatment outcome. Phenotypic hypersusceptibility of HIV-1, defined as having a greater than 2.5 fold increase in susceptibility to a drug compared with a wild-type reference strain using the phenotypic resistance assay by Monogram Biosciences (formerly ViroLogic), occurs with protease inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) 17-20. HIV-1 variants with phenotypic NNRTI hypersusceptibility are more likely to be resistant to nucleoside analogs 17, 20-22. In patients, the presence of HIV-1 with NNRTI-hypersusceptibility is associated with improved responses to an NNRTI-containing regimen compared to patients with variants that are not hypersusceptible 8, 20, 21, 23.

The genetic basis for hypersusceptibility to NNRTIs has been the subject of some debate. Early reports identified an association between phenotypic NNRTI-hypersusceptibility and thymidine analog mutations (i.e., those at codons 41, 67, 70, 210, 215 and 219 of reverse transcriptase) 17, 22. One study reported a correlation between phenotypic efavirenz hypersusceptibility and a number of different reverse transcriptase mutations in univariate analyses, including T215Y/F, D67N, H208Y, K103R, and V179D 24. Subsequent analyses showed an association between several mutations and phenotypic hypersusceptibility, and stepwise logistic regression found that 3 codons, 118, 208, and 215, remained independently predictive of efavirenz hypersusceptibility 25. A study of site-directed mutants of HIV has shown that combinations of mutations at codons 118, 208, and 215 confer EFV hypersusceptibility 26.

However, there have been limited data correlating NNRTI-hypersusceptibility, as defined genetically, with treatment outcome. One study identified an association between the presence of M41L, M184V, L210W, and T215Y with improved transient virologic outcomes, but did not assess the impact of other mutations potentially associated with NNRTI-hypersusceptibility 27.

ACTG 368 was a clinical trial that evaluated whether abacavir improved virologic and immunologic responses to efavirenz and indianvir in patients with prior nucleoside analog experience. We evaluated whether a genotypic score for efavirenz hypersusceptibility was associated with treatment responses in patients enrolled in this trial.

Methods

Study Design

ACTG 368 was a phase II, randomized, double-blind, multi-center clinical trial comparing the virologic responses to IDV+EFV or IDV+EFV+ABC in nucleoside-experienced patients. In addition, there was a comparison of q 8h IDV dosing (which was standard at the time this trial was developed) versus IDV twice a day (BID), leading to a factorial design with 4 arms described below. This protocol was initially designed as a follow-up study for subjects assigned to the dual nucleoside arm (ZDV [or d4T] + 3TC) of ACTG 320 2. Subjects enrolled in ACTG 320 had nucleoside experience (median 21 months at entry) and were naive to protease inhibitors (PIs) and 3TC. Patients who had not enrolled in ACTG 320 were eligible for ACTG 368 if they were naïve to protease inhibitors (PIs) and NNRTIs, had at least 2 months of therapy with ZDV (or d4T) + 3TC, and a documented CD4 count of <250 cells/mm3 within the 3 months before initiation of these drugs.

Subjects were stratified by their screening CD4 cell count and prior participation in ACTG 320. In addition to the 4 treatment arms of the factorial design (arms 1 through 4 below), ACTG 368 also offered arm 5 to patients with prior NNRTI experience.

Arm 1: IDV 1000 mg q8h + EFV 600 mg QD + abacavir placebo BID

Arm 2: IDV 1000 mg q8h + EFV 600 mg QD + abacavir 300 mg BID

Arm 3: IDV 1200 q12h + EFV 300 mg q12h + abacavir placebo BID

Arm 4: IDV 1200 mg q12h + EFV 300 mg q12h + abacavir 300 mg BID

Arm 5: IDV 1000 mg q8h + EFV 600 mg QD + open-label abacavir 300 mg BID

This study pre-dated the use of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors. The doses of IDV in this study were increased compared to the then standard dosing of 800 mg q8h, based on pharmacokinetic data indicating that EFV reduced plasma concentrations of IDV (Sustiva package insert). These doses were not based on clinical data of virologic responses.

The study planned to accrue 300 NNRTI-naïve subjects to the randomized treatment arms: 120 subjects each on Arms 1 and 2, and 30 subjects each on Arms 3 and 4. Subjects who had a screening CD4 cell count ≤ 50 cells/mm3 were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to Arms 1 and 2; subjects with >50 CD4 cell/mm3 were randomized with equal probability to Arms 1-4 until the accrual goal of Arms 3 and 4 was achieved. NNRTI-experienced subjects previously enrolled in ACTG 320 were assigned to receive open-label triple combination therapy (Arm 5).

Subjects were enrolled in ACTG 368 between April 23, 1997 and March 13, 1998. After November 10, 1998, all subjects on Arms 3 and 4 had their IDV BID and EFV dosing changed to that given in Arms 1 and 2, while maintaining blinding of ABC. This decision was based on an interim analysis that suggested inferior responses to BID IDV, and was made in conjunction with Merck & Co., Inc.'s decision to discontinue other trials of BID IDV. Subjects were followed until 48 weeks after the last subject enrolled, or a maximum of 96 weeks. Subjects who developed virologic failure after week 16 were eligible to receive open-label IDV + EFV + ABC.

This study was conducted according to procedures approved by the human subjects review boards at each institution, and these procedures were consistent with the ethical standards outlined by the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2000). The studies correlating HIV-1 drug resistance with virologic outcome were planned at the time the clinical trial was originally designed. The studies of EFV hypersusceptibility were planned after the initial resistance analyses were completed.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4 counts

Samples for both plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4 count were tested at pre-entry, entry and at weeks 2, 4, 8, and every 8 weeks thereafter. Plasma HIV-1 RNA was quantitated using the Roche Amplicor Monitor assay (version 1.0) by a central laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. CD4 counts were measured at individual sites by laboratories that had successfully undergone proficiency testing through the ACTG.

Phenotypic drug resistance testing

VircoLabs performed phenotypic drug resistance testing, using a recombinant virus assay 28. Resistance was tested to 14 drugs, and reported as a fold-change in IC50 relative to a drug-sensitive reference strain tested in parallel. Testing was limited to baseline samples from the groups that received q8h IDV (Arms 1, 2, and 5).

Genotypic drug resistance testing

Testing for mutations conferring resistance to protease and reverse transcriptase inhibitors was performed using DNA sequencing of PCR products amplified from patient plasma (ViroSeq kit, version 2.0, Celera Diagnostics, Foster City, CA) 29, 30. Baseline and failure samples were tested from the q8h IDV groups only (Arms 1, 2, and 5). Sequence analysis was performed in batch after the conclusion of the study by 3 laboratories (University of Rochester, Columbia, and Johns Hopkins). Base calls were made using the version 2.2 software provided with the sequencing kit. Nucleotide mixtures were identified if the minority peak on one primer was at least 30% of the major peak, and if its presence was confirmed on a primer hybridizing to the complementary DNA strand. Mixtures of wild-type and resistance mutations were classified as being resistant at that site. Mutations were identified as being associated with resistance to specific drugs, using criteria established by an IAS-USA panel 31. For analyses of genotypic ABC resistance and outcome, the Stanford algorithm (version 4.3.0.2) was used to define ABC susceptible, and intermediate- or high-level resistant viruses.

Statistical Methods

Data presented include all subject visits, laboratory data, and events that were reported to the database through May 4, 1999. The primary endpoint of the study was virologic failure, defined as either an early failure occurring before week 16 (2 consecutive RNA values ≥ 5,000 copies/mL and 1 log10 above nadir, or 2 consecutive RNA values above baseline, if baseline was >500 copies/mL) or a confirmed HIV-1 RNA value of ≥ 500 copies/mL at week 16. Missing week 16 values were defined as virologic failures, unless both the week 12 and 20 values were <500 copies/mL. Additional analyses of virologic failure were performed at weeks 32 and 48. Treatment failure at these time points was defined as an HIV RNA value of ≥ 500 copies/mL, a missing HIV RNA value, or discontinuation of study treatment. Failures occurring prior to week 32 or 48 were included in analyses of those later time points. A nadir of 500 was used for RNA copy numbers ≤ 500 copies/mL.

Analyses of the BID versus q8h IDV groups showed no clear differences in treatment outcome or toxicities, although the small numbers of subjects and abbreviated duration of treatment limited the power of this comparison to detect a difference. All efficacy data presented here are therefore limited to the pooled ABC versus placebo groups (arms 1+3 vs. 2+4). Analyses excluding the study patients randomized to the BID arms (arms 3 and 4) did not alter the results (data not shown).

These analyses were stratified by screening CD4 count and prior enrollment in ACTG 320. Stratified exact tests based on the product hypergeometric distribution (an exact version of the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test) were used. Exact tests for homogeneity across all 4 strata as well as collapsed over one or the other factor were used to rule out the possibility of treatment-strata interaction. Evidence suggestive of a treatment-strata interaction was defined as a p-value <0.05. The ABC-containing arm is the reference group for interpretation of odds ratios and confidence intervals. All pair-wise comparisons were made using the two-sided Fisher's exact test, unless stated otherwise.

The geometric mean of the pre-entry and entry RNA values was used for the baseline value. If a baseline value was outside the range of the assay (500 – 750,000 copies/mL), then the value was imputed to be the upper or lower limit of the assay. The arithmetic mean of pre-entry and entry CD4 count was used to calculate the baseline value. For both RNA and CD4 values, if a subject had only one measurement available, that value was used as the baseline value.

For the week 16 safety analyses, all events are included from dispensation of study treatment through the week 16 study visit (or 20 weeks if week 16 was missed) or the date of treatment discontinuation plus 56 days, whichever came first. Additionally for the 32 and 48 week analyses, events were also censored at the time subjects who had developed virologic failure registered to open-label therapy.

Analyses were performed via logistic regression to detect associations between baseline HIV drug resistance and virologic outcome; likelihood-ratio tests were used for significance and the method of profile likelihood was used for confidence intervals. A negative virologic outcome comprised: (i) failure by week 32 as in the analysis of treatment efficacy and (ii) treatment discontinuation prior to week 16.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 309 subjects were enrolled; 283 were NNRTI-naive and 26 were NNRTI-experienced. Of the 283 NNRTI-naive subjects, 71 (25%) had CD4 cell counts ≤ 50 cells/mm3 at screening; 166 (59%) were previously enrolled in ACTG 320. Seventy-nine percent of subjects were men, with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and a mean age of 40 years (Table 1). Mean plasma HIV-1 RNA at entry was 4.3 log10 and mean CD4 cell count was 133 cells/mm3. Median duration of prior nucleoside exposure was 99 weeks. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the ABC and placebo treatment groups.

Table 1.

| Baseline Characteristics | IDV+EFV (n=143) (Arms 1+3) |

ABC+IDV+EFV (n=140) (Arms 2+4) |

TOTAL (n=283) (Arms 1-4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 112 (78.3) | 111 (79.3) | 223 (78.8) |

| Women | 31 (21.7) | 29 (20.7) | 60 (21.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 51 (35.7) | 54 (38.6) | 105 (37.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 60 (42) | 56 (40) | 116 (41) |

| Hispanic (any race) | 30 (21) | 25 (17.9) | 55 (19.4) |

| Asian, Pac. Isl. | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (1.8) |

| Amer. Ind./Alask Nat. | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Age | |||

| mean | 40.3 | 39.1 | 39.7 |

| std.dev. | 9.6 | 8.5 | 9.1 |

| range | 21-74 | 21-67 | 21-74 |

| IV Drug Use | |||

| Never | 119 (83.2) | 108 (77.1) | 227 (80.2) |

| Currently | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Previously | 23 (16.1) | 30 (21.4) | 53 (18.7) |

|

Plasma HIV-1 RNAa (log10 copies/mL) |

|||

| mean | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| std. dev. | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| range | 2.7 – 5.88 | 2.7 – 5.88 | 2.7 – 5.88 |

|

CD4 cell counta (cells/mm3) |

|||

| mean | 125.5 | 141.2 | 133.3 |

| std. dev. | 9.6 | 8.5 | 9.1 |

| range | 0-723 | 0-420 | 0-723 |

Plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4 values based on 142 subjects in the IDV+EFV group.

Effect of abacavir addition on plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4 responses

The efficacy of ABC versus placebo was analyzed in the 283 subjects randomized to Arms 1-4. There were no significant differences in the rates of premature discontinuation of study follow-up in the ABC and placebo groups. Discontinuation of study treatment occurred in 13% (36/283) by week 16. Premature discontinuation of assigned study treatment was significantly more common in the ABC arm (19% versus 6%, p=0.001). The primary reasons for treatment discontinuation were toxicity and problems with protocol compliance.

At week 16, there were no differences between the ABC and placebo groups in the proportion of virologic failures (p=0.509, Product Hypergeometric Exact test, Table 2). Similar results were seen at weeks 32 and 48 (data not shown) and when virologic failure was defined as ≥ 500 copies/mL (Table 2). There were no differences in the mean change in CD4 count from baseline comparing the ABC and placebo groups at either week 16 (p=0.764) or 48 (p=0.589).

Table 2. Viral load responses: Abacavir versus placebo groups.

| ABC group | Placebo Group | Odds Ratio (95% CI)a |

P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 16 | ||||

| Failure Analysisc | ||||

| Total non-failures | 102 (73%) | 99 (69%) | ||

| Total failures | 38 (27%) | 44 (31%) | 1.20 (0.69, 2.09) | 0.509 |

| Suppression status (intent to treat)d | ||||

| RNA<500 | 99 (78%) | 98 (73%) | ||

| RNA≥500 | 28 (22%) | 37 (27%) | 1.33 (0.725, 2.45) | 0.387 |

| Suppression status (on initial therapy)e | ||||

| RNA<500 | 94 (86%) | 97 (75%) | ||

| RNA≥500 | 15 (14%) | 33 (25%) |

ABC group is the reference group

Product Hypergeometric Exact Test

Includes all subjects in an intent-to-treat analysis, using the primary virologic failure definition for the study

Uses a definition of virologic failure of ≥ 500 copies/mL and includes all subjects regardless of whether they were on their originally assigned therapy

Uses a definition of virologic failure of ≥ 500 copies/mL and includes only subjects on their originally assigned therapy

Not done

Safety

There were no significant differences in grade 3 or 4 symptoms or laboratory toxicities in the ABC and placebo groups. The number of definite or probable ABC hypersensitivity reactions, based on a retrospective review by the study chair, who was blinded to treatment assignment, was 3, all of whom received ABC (frequency of 1.5% in 201 ABC recipients). In secondary analyses, there was evidence for a delayed time to grade 3 or 4 symptoms in the placebo groups (data not shown).

Baseline HIV-1 drug resistance

Analyses of HIV-1 drug resistance at baseline were performed in ACTG 368 subjects who were randomized to the Q8h dosing regimens (Arms 1 and 2) and the NNRTI-experienced subjects receiving open-label IDV + 3TC + ABC (Arm 5). Only samples with >500 copies/mL were tested with phenotypic or genotypic tests. Phenotypic testing was performed on 204 samples at baseline only. Genotypic resistance testing was performed at baseline in all subjects in arms 1, 2, and 5; on the first failure treatment sample in subjects who had a rebound of plasma HIV-1 RNA to >500 copies/mL after initial suppression to <500 copies/mL; and on the last on-treatment sample (through 48 weeks) in subjects who never achieved virologic suppression to <500 copies/mL during study followup.

Genotypic resistance test results were available for 197 subjects: at baseline and follow-up for 69/197 subjects (35%), at baseline only for 117/197 subjects (59%), and at follow-up only for 11 subjects (6%). Baseline demographic characteristics, CD4 count, and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of subjects undergoing phenotypic or genotypic resistance testing were similar to those of ACTG 368 as a whole (data not shown).

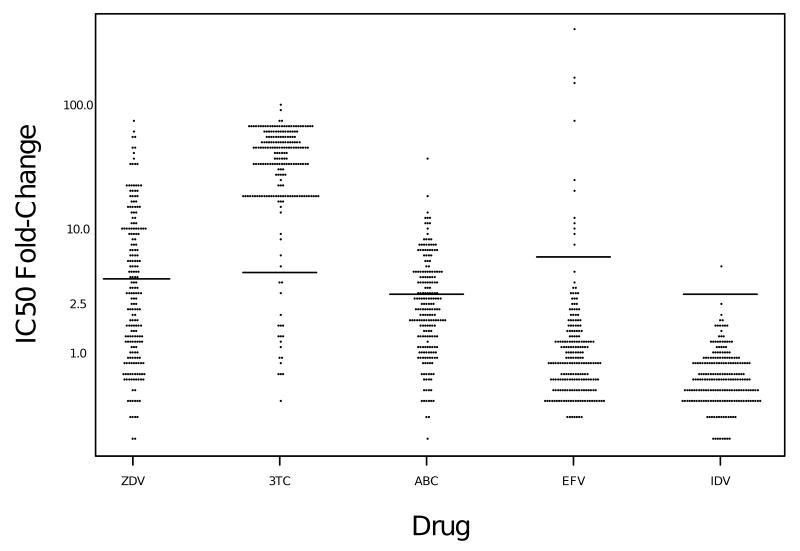

Biological resistance thresholds of 4-fold for ZDV, 4.5-fold for 3TC, 3-fold for ABC, 6-fold for EFV, and 3-fold for IDV, established by VircoLabs, were used. Using these resistance thresholds, 44% were resistant to ZDV, 91% to 3TC, 37% to abacavir, 5% to EFV, and 1% to IDV at baseline (Figure 1). Of the 186 subjects who had genotypic resistance test results at baseline, nearly two-thirds had one or more nucleoside analog mutations (NAMs), as defined by the IAS-USA 31 in combination with M184V (Table 3). NNRTI-resistance mutations were infrequent at baseline, occurring in only 13/183 subjects (6%). All but 3 of these subjects gave a history of past NNRTI use and were assigned to open-label ABC+IDV+EFV (2 of the remaining 3 were randomized to EFV+IDV and 1 to ABC+IDV+EFV). No primary IDV resistance mutations were present at baseline, consistent with the reported lack of prior treatment with protease inhibitors, and nearly all had 2 or fewer secondary IDV-resistance mutations at baseline.

Figure 1. Fold-change in IC50 at baseline in ACTG 368 subjects.

Jitter plot represents the fold-change in IC50 at baseline for each virus and drug tested. Resistance thresholds, defined by VircoLabs, are shown as horizontal lines (4-fold for ZDV, 4.5-fold for 3TC, 3-fold for ABC, 6-fold for EFV, and 3-fold for IDV)

Table 3. Genotypic Resistance at Baseline in ACTG 368.

| Drug / Class | Resistance Pattern | ABC+IDV+EFV (n=97) |

IDV+EFV (n=89) |

Total (n=186) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nRTI | NAMsa alone | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 9 (5%) |

| NAMs+184Vb | 63 (65%) | 54 (61%) | 117 (63%) | |

| NAMs+69D or 74V | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (2%) | |

| NAMs+184V+69D or 74V | 5 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (4%) | |

| M184V alone | 19 (20%) | 16 (18%) | 35 (19%) | |

| M184V + T69D or L74V | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Q151Mc complex | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) | |

| No nRTI resistance | 3 (3%) | 7 (8%) | 10 (5%) | |

| NNRTI | K103N alone | 5 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (4%) |

| Y188L | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | |

| G190A/S | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | |

| P236L | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| No NNRTI resistance | 87 (%) | 86 (%) | 174 (94%) | |

| IDV | Primary Mutationsd | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Secondary Mutationse | ||||

| 0 | 50 (52%) | 47 (53%) | 97 (52%) | |

| 1 | 32 (33%) | 36 (40%) | 68 (37%) | |

| 2 | 13 (13%) | 6 (7%) | 19 (10%) | |

| 3 | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

NAMs include any one of the following reverse transcriptase mutations: M41L, E44D, D67N, K70R, V118I, L210W, T215Y/F, K219E/Q.

1 sample, from subject in the ABC arm had Q151M in addition to NAMs + M184V.

Q151M complex is defined as the presence of one or more of the following reverse transcriptase mutations: A62V, V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M.

Primary or major IDV resistance mutations are defined as one or more of the following protease mutations: M46I/L, V82A/F/T, I84V.

Secondary or minor IDV resistance mutations are defined as one or more of the following protease mutations: L10I/R/V, K20M/R, L24I, V32I, M36I, I54V, A71V/T, G73S/A, V77I, L90M.

Resistance patterns at failure

At the time of failure, approximately 60% had one or more NAMs, most of these in combination with M184V (Table 4). Only 7/69 patients with both baseline and failure genotypic testing had an increase in the number of NAMs from baseline to failure. The proportion of patients with an NNRTI-resistance mutation at failure was 67% (54/80); 61% (49/80) had K103N, either alone or in combination with other NNRTI-resistance mutations. Other NNRTI-resistance mutations observed at failure (usually in combination with K103N) were L100I (9 patients, 11%), V108I (5 patients, 6%), P225H (3 patients, 4%), Y181C (1 patient, 1%), Y188L (1 patient, 1%), G190A (6 patients, 7%), and G190S (2 patients, 3%). Three subjects developed primary IDV resistance mutations, all in the IDV+EFV arm. Ninety-five percent of subjects had 2 or fewer secondary IDV resistance mutations at failure.

Table 4. Genotypic Resistance at Failure in ACTG 368 (n=80).

| Drug / Class | Resistance Pattern | ABC+IDV+EFV a (n=36) |

IDV+EFV b (n=44) |

Total (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nRTI | NAMsa alone | 2 (6%) | 8 (18%) | 10 (13%) |

| NAMs + M184V | 18 (50%) | 14 (32%) | 32 (40%) | |

| NAMs + T69D or L74V | 2 (6%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (5%) | |

| NAMs + 184V+69D or 74V | 0 | 2 (5%) | 2(3%) | |

| M184V alone | 9 (25%) | 5 (11%) | 14 (17%) | |

| T69D or L74V alone | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Q151M complexb | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (4%) | |

| No nRTI resistance | 4 (%) | 9 (%) | 13 (16%) | |

| NNRTI | K103N (alone) | 12 (33%) | 17 (39%) | 29 (36%) |

| K103N + V108I | 2 (6%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (5%) | |

| K103N + P225H | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | |

| K103N+Y188L | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| K103N+L100I | 2 (6%) | 6 (14%) | 8 (10%)# | |

| K103N+G190A/S | 1 (3%)** | 3 (7%)ˆ | 4 (5%) | |

| Y181C | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| G190A/S | 1 (3%)*** | 2 (5%)ˆˆ | 3 (4%) | |

| L100I+G190A/S | 0 | 1 (2%)** | 1 (1%) | |

| K103N+V108I+P225H | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| No NNRTI resistance | 14 (39%) | 12 (27%) | 26 (33%) | |

| IDV | Primary Mutationsc | 0 (0%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (4%) |

| Secondary Mutationsd | ||||

| 0 | 20 (56%) | 16 (36%) | 36 (45%) | |

| 1 | 9 (25%) | 23 (52%) | 32 (40%) | |

| 2 | 6 (17%) | 2 (5%) | 8 (10%) | |

| 3 | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (3%) |

NAMs include any one of the following reverse transcriptase mutations: M41L, E44D, D67N, K70R, V118I, L210W, T215Y/F, K219E/Q.

Q151M complex is defined as the presence of one or more of the following reverse transcriptase mutations: A62V, V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M.

Primary or major IDV resistance mutations are defined as one or more of the following protease mutations: M46I/L, V82A/F/T, I84V.

Secondary or minor IDV resistance mutations are defined as one or more of the following protease mutations: L10I/R/V, K20M/R, L24I, V32I, M36I, I54V, A71V/T, G73S/A, V77I, L90M.

G190A

G190S

2 G190A, 1 G190S

1 G190A, 1 G190S

5/8 of these samples also acquired the L74V muatation. 4/5 of these samples were from subjects assigned to the EFV+IDV arm. L74V was present at failure only in samples that also had the K103N and L100I mutations, and was not present in any of the baseline samples of the 4 subjects with L74V at failure, who had genotypic testing at baseline.

L100I and mutations at codon 190 have been less commonly observed than K103N with either V108I or P225H in prior published studies of EFV treatment 32, 33. We therefore evaluated whether there were factors that favored the development of these normally less common EFV resistance mutations. L100I and G190S/A occurred at a similar prevalence in the 2 treatment arms (4/22 [18%] in the ABC arm versus 9/32 [28%] in the EFV+IDV arm) and in samples with or without concomitant nucleoside resistance (3/13 [23%] in those without nucleoside resistance mutations versus 10/41 [24%] in those with nucleoside resistance). There was also no influence of treatment assignment on the frequency of primary and secondary resistance mutations to IDV (16/36 [44%] versus 28/44 [64%] in the ABC and placebo arms, respectively) or NNRTIs (22/36 [61%] versus 32/44 [73%] in the ABC and placebo arms, respectively). We did note that a relatively high proportion of samples with the K103N and L100I mutations also accumulated the nucleoside resistance mutation L74V, even though most of these were assigned to the nucleoside-sparing EFV+IDV arm (Table 4). None of these patients had evidence of L74V at entry into the study, by direct sequence analysis. We also found no evidence of L74V as a minority variant in clones analyses from 2 of these patients at baseline (100 clones per patient). No other samples at failure had the L74V mutation in this study.

Baseline Drug Resistance and Outcome

Baseline phenotypic resistance was evaluated as a predictor of failure at week 16, using the same definition of failure at those weeks as the analyses of treatment efficacy. All patients who withdrew early from the study were counted as virologic failures in this analysis. Analysis was limited to subjects who had phenotypic resistance testing performed at baseline and had HIV-1 RNA data at the appropriate time point. The risk of virologic failure was not significantly altered by HIV-1 phenotypic susceptibility to ABC or the ACTG 368 regimen at baseline (Table 5). Similar results were obtained when patients who withdrew early from the study were censored from the analysis, and when failure at weeks 24 or 32 was evaluated (data not shown). When a genotypic score for ABC resistance was used (Stanford algorithm version 4.3.0.2), the group with intermediate- or high-level resistance to abacavir had a reduced odds of virologic failure (25/118 or 21% failures), compared to the abacavir-susceptible group (26/68 or 38%, OR=0.44, 95% CI 0.22-0.84, p=0.01). Because thymidine analog mutations have been associated with both abacavir resistance and efavirenz hypersusceptibility, this finding suggested that the genotypic score for ABC resistance may actually have been detecting EFV hypersusceptibility.

Table 5. Baseline Phenotypic HIV-1 Drug Resistance as a Predictor of Virologic Failure.

| Parameter | N | Odds Ratio for Virologic Failure by Week 16 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Abacavir sensitivity a | ||

| all subjects | 202 | 1.19 (0.62, 2.26) |

| subjects receiving ABC | 109 | 1.00 (0.44, 2.32) |

| subjects not receiving ABC | 93 | 1.60 (0.56, 4.57) |

| Abacavir log10 IC50 fold change b | ||

| all subjects | 202 | 0.60 (0.27, 1.31) |

| subjects receiving ABC | 109 | 0.89 (0.30, 2.60) |

| subjects not receiving ABC | 93 | 0.35 (0.10, 1.21) |

| Abacavir IC50 fold change | ||

| all subjects | 202 | |

| 0.0 - <4.0 | 145 | 1.00 |

| 4.0 - <8.0 | 43 | 0.59 (0.26, 1.33) |

| ≥ 8.0 | 14 | 0.61 (0.16, 2.28) |

| subjects receiving ABC | 109 | |

| 0.0 - <4.0 | 79 | 1.00 |

| 4.0 - <8.0 | 23 | 0.57 (0.19, 1.70) |

| ≥ 8.0 | 7 | 0.82 (0.15, 4.49) |

| subjects not receiving ABC | 93 | |

| 0.0 - <4.0 | 66 | 1.00 |

| 4.0 - <8.0 | 20 | 0.62 (0.18, 2.09) |

| ≥ 8.0 | 7 | 0.41 (0.05, 3.66) |

| Overall Sensitivity Score c | 202 | 1.32 (0.72, 2.45) |

Odds ratio reported is for virologic failure for a subject having an IC 50 fold-change ≤ 3.0 as compared to a subjects having an IC 50 fold-change > 3.0 for ABC.

Odds ratio for virologic failure for a one-unit increase in log 10 (IC 50 fold change) for ABC

Odds ratio for a one-unit increase in overall sensitivity score, which is the total number of drugs in the regimen to which a subject's virus is sensitive (range 1-3).

Efavirenz Hypersusceptibility and Outcome

We postulated that HIV-1 hypersusceptibility to EFV at baseline may have contributed to the high response rates seen in this study and may have made it more difficult to detect a benefit of ABC. Efavirenz hypersusceptibility cannot reliably be detected with the Virco phenotypic assay; therefore we evaluated a genotypic score for EFV hypersusceptibility, based on mutations reported to be associated with phenotypic EFV hypersusceptibility in a recent abstract (D67N, K103R, V179I, H208Y, and T215F/Y) 24. We found that having 2 or more of these mutations was significantly associated with a reduced risk of virologic failure in ACTG 368 (p=0.0017), and that greater numbers of mutations were associated with a greater reduction in risk of failure (Table 6). We did not detect an interaction between treatment assignment and having 2 or more EFV hypersusceptibility mutations at baseline, (p = 0.16), suggesting that the associations of these mutations with outcome were similar in the two treatment groups. Similar results were obtained when NNRTI-experienced patients in the open-label ABC + EFV + IDV were excluded from the analyses.

Table 6. Associations between 3 Genotypic EFV-Hypersusceptibility Scores and Virologic Failure.

| No. of mutations | % with Virologic Failure | Odds Ratio for Virologic Failure (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Score A (RT mutations D67N, K103R, V179I, H208Y, L210W, and T215F/Y) | ||

| None | 44% | 1.00 |

| One | 31% | 0.56 (0.23, 1.3) |

| Two | 19% | 0.30 (0.12, 0.71) |

| Three | 13% | 0.19 (0.05, 0.56) |

| Four or Five | 7% | 0.10 (0.01,0.54) |

| Score B (RT mutations M41L, E44D, D67N, T69D, V118I, H208Y, L210W, T215Y/F and insertions at RT codon 69) | ||

| None | 41% | 1.00 |

| One | 36% | 0.81 (0.19, 2.99) |

| Two | 24% | 0.37 (0.13, 0.95) |

| Three | 21% | 0.44 (0.16, 1.10) |

| Four or more | 16% | 0.28 (0.11, 0.67) |

| Score C (mutations at RT codons 118, 208, and 215) | ||

| None | 39% | 1.00 |

| One | 22% | 0.42 (0.21, 0.86) |

| Two | 23% | 0.46 (0.15, 1.25) |

| Three | 0% | 0 (0, 0.61) |

Because there is an overlap between some of the mutations associated with EFV-HS and those associated with resistance to ABC, we evaluated whether EFV-HS as defined by this algorithm was associated with virologic failure when phenotypic resistance to ABC is taken into account. Eighty-four percent (57/68) of viruses resistant to ABC (defined as a fold-change in IC50 > 3) were found to be EFV-HS (defined as having > 2 mutations listed above)., whereas 52% (53/103) of those samples susceptible to ABC were EFV-HS. In both ABC-resistant and -susceptible subgroups, reduced odds of virologic failure were observed for the EFV-HS samples (susceptible OR=0.44, p=0.06; resistant OR=0.18, p=0.01). Thus, there appears to be an association of EFV-HS with improved outcome, even if the virus is phenotypically susceptible to ABC.

We also evaluated 2 additional EFV-HS scores, using a somewhat different set of mutations identified in a recently published analysis as being associated with phenotypic EFV-HS. One score was based on all mutations that were associated with phenotypic EFV-HS (M41L, E44D, D67N, T69D, V118I, H208Y, L210W, T215Y/F, and insertions at codon 69), and another was based on the three mutations that remained significant during multivariate analysis of that same dataset (V118I, H208Y, T215Y) 25. Using either of these EFV-HS scores, having a greater number of mutations was also associated with a reduced odds of virologic failure, although the association between the number of mutations and a progressive decrease in odds ratio for virologic failure was not as consistent as was observed with the first score (Table 6).

Discussion

We studied the effect of including ABC in combination with EFV and IDV in nucleoside-experienced, and PI- and NNRTI-naive patients with advanced HIV disease. It should be noted that the PI regimens evaluated in this study do not reflect current standards of care, in that ritonavir was not used to augment protease inhibitor levels. In addition, it should be noted that EFV reduces levels of IDV. Although the doses of IDV used in this study were higher than the then-standard dose of 800 mg q8h, in an attempt to compensate for this interaction, these doses had not been previously validated based on virologic response data in patients. We found no evidence that adding ABC to EFV+IDV in this patient population was beneficial based on the primary study endpoint of virologic failure at week 16. We also saw no evidence for a consistent difference between the 2 regimens at later time points. One possible contributing factor to the lack of benefit of ABC was decreased tolerability in this patient population, as evidenced by increased treatment discontinuation rates in the ABC groups.

Another potential explanation for the observed lack of benefit of ABC is reduced or absent antiviral effect due to the presence of cross-resistance to ABC in baseline HIV-1 variants from this nucleoside-experienced population. However, we found no evidence that phenotypic resistance to ABC was adversely associated with virologic outcome. In addition, we found no evidence that a phenotypic regimen sensitivity score, which has been associated with outcome in other studies 7, 12, predicted virologic failure in this trial.

However, we did observe that with 3 different genotypic scoring systems, EFV-hypersusceptibility at baseline was associated with a reduced odds of virologic failure in this study. We believe that the presence of EFV-hypersusceptibility may have contributed to the relatively high rates of virologic suppression that were seen in both the EFV+IDV and EFV+IDV+ABC arms, in this PI- and largely NNRTI-naive patient population, and that this may have made it difficult to detect a benefit of ABC addition. A recent study of site-directed mutants strongly supports a direct role for V118I, H208Y, and T215Y mutations in EFV-HS26, although it does not rule out contributions to EFV-HS by other mutations in HIV reverse transcriptase. Assessing the significance of specific mutations in predicting virologic failure or success is complicated by the fact that certain mutations may cluster together. Our studies therefore do not address the issue of what is the best genotypic algorithm for EFV-HS, but they do indicate that an increasing number of mutations associated with EFV-HS is associated with improved virologic success rates on an EFV-containing regimen. These effects appeared to be independent of the treatment regimen or the presence of ABC resistance.

Overall, the genetic patterns of resistance at first failure in this trial were similar to those seen in other trials of EFV-based regimens, with K103N present in approximately 90% of samples having an NNRTI-resistance mutation. K103N was also the most common resistance mutation to emerge during therapy, with little evolution in nucleoside analog resistance and only a few patients (primarily in the dual drug arm) developing primary protease inhibitor resistance mutations.

There did appear to be some differences in the relative prevalence of other NNRTI-resistance mutations in this trial, compared to the earlier trials in which EFV was given either in combination with IDV or zidovudine and lamivudine 32, 33. In those earlier trials, the accumulation of V108I or P225H occurred commonly after the emergence of K103N, with K103N+L100I or G190S/A occurring uncommonly. In contrast, in ACTG 368, the V108I and P225H mutations were less common than L100I or mutations at codon 190. The reasons for these differences are unclear, and we were unable to identify factors, such as treatment assignment or concomitant nucleoside resistance, that predicted the development of mutations at 100 or 190 in this trial.

It is interesting to note that 5 of 8 patients with the L100I mutation in ACTG 368 also acquired the L74V mutation, even though 4 of those 5 patients were assigned to the nucleoside sparing arm. In studies using site-directed mutagenesis, L74V has been demonstrated to improve the replication of HIV containing G190 mutations, in the absence of drug 34, 35, raising the question of whether this mutation was selected for in our study primarily for its effects on HIV replication efficiency rather than drug resistance. Studies of the effects of L74V in combination with K103N+L100I in the laboratory strain NL4-3 have confirmed that L74V improves the replication efficiency of K103N+L100I 36.

Ait-Khaled and colleagues also observed a relatively high frequency of L74V (39%), attributed in part to selection by ABC. Our study is interesting in that the majority of the L74V variants appear to have been selected for in the absence of a nucleoside analog. It is interesting to consider that resistance mutations can have broad-ranging effects, and may be selected for independent of direct selection by the drug(s) they confer resistance to. This finding provides an additional rationale for the use of resistance testing in treatment-experienced patients.

Conclusions

In summary, giving IDV in combination with EFV in highly nucleoside-experienced, PI- and NNRTI-naive subjects led to relatively high rates of virologic suppression. In the group as a whole, we were unable to demonstrate an additional benefit of ABC. Our inability to detect an impact of ABC on virologic outcome in the ACTG 368 patient population as a whole appears to be due to a combination of problems with tolerability in patients with advanced HIV disease, and the potent efficacy of EFV+IDV in this nucleoside-experienced, PI- and NNRTI-naive population, which, we postulate, may have been augmented by the presence of HIV variants with EFV-hypersusceptibility at baseline. The good response rates in the control arm could have made it more difficult to detect a benefit of ABC addition, with the sample size studied. These findings suggest that nucleoside-sparing regimens can be used effectively in this specific patient population. The utility of such regimens in current clinical practice is limited, however, given the infrequent occurrence of patients who are highly nucleoside-experienced but PI- and NNRTI-naive.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study subjects who participated in this trial, and acknowledge the support of the following study personnel, AIDS Clinical Trials Units and NIH grants: John McNeil, MD - Howard University (A5301); Jose Castro, MD and Leslie Thompson, RN, BSN - University of Miami (A0901) AI27675; Richard B. Pollard and Monica Pickthall- University of Texas, Galveston (A6301) AI32782; Michael Kilby, MD and Melissa Armstrong, RN- University of Alabama at Birmingham (A5801); Susan L. Koletar, MD; Kathy J Watson, RN- Ohio State University (A2301) AI25924; Henry H. Balfour, Jr. and Nancy V. Reed- University of Minnesota (A1501); Charles B. Hicks, MD and Sherri Swan, RN- Duke University Medial Center (A1601); Michael Klebert, RNP and Michael Royal, RPh- Washington University (St. Louis) (A2101) AI25903; Judith Feinberg, MD and Sharon Kohrs, RN, BSN, ACRN- University of Cincinnati (A2401); Jane Dowling RN and Charles Gonzalez-NYU/Bellevue (A0401); David Ragan, RN and Cheryl Marcus, RN- University of North Carolina (A3201) RR00046, AI25868 and AI50410; Ilene Wiggins, RN and Dorcas Baker, BSN- Johns Hopkins University (A0201); Richard Reichman, MD and Jane Reid, RN- University of Rochester Medical Center (A1101) AI27658 and RR00044; - Indiana University Hospital (A2601); Carol DeQuattro, RN and Mary Albrecht, MD- Harvard (Massachusetts General Hospital) (A0101) AI027659; Juan J.L Lertora, MD, PhD and Rebecca Clark, MD, PhD- Tulane University (A1701) AI3844 and RR05096; Robert Murphy, MD (Northwestern University) and Harold Kessler, MD (Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke's) (A2701); - University of Hawaii (A5201); - Vanderbilt University (A7602); Susan Cahill and Gary Dyak - University of California, San Diego Antiviral Research (A0701) AI27670; - University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (A6201); Margrit Carlson, MD and Ann Johiro, RN, NP- UCLA School of Medicine (A0601) AI27660, AI38858 and RR00865; Beck A. Royer, PA-C and Sheryl Storey, PA-C - University of Washington (Seattle) (A1401) AI27664.; Henry Sacks, PhD, MD and Eileen Chusid, PhD- Mount Sinai Medical Center (A1801); Barb Gripshover, MD and Ronald Johnson, RN- Case Western Reserve University (A2501) AI25879; Judy Aberg, MD and Diane Havlir, MD- San Francisco General Hospital (A0801); Univ. of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver (A6101); Pat Cain, RN and Debbie Slamowitz, RN- Stanford University (A0501); University of Southern California (A1201); Carolyn Francis, CNNP and Anastasia Lee, RN-Georgetown University Hospital (A9327). We would also like to acknowledge the support of 5R01 AI-51164 to V. DeGruttola and 2 R01 AI-041387 to L. Demeter.

Potential conflicts of interest: L. Demeter, past research support from ViroLogic, Virco, Visible Genetics, and Applied Biosystems/Celera; advisory board member, GlaxoSmithKline; past participation on speaker's bureau for Virco. M. Fischl, research grants from Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and member of the advisory board of Merck & Co. W. Spreen, employee of GlaxoSmithKline. B-Y. Nguyen, employee of Merck. S. Hammer, scientific advisor to Merck, Pfizer, Progenics, and Tibotec; member, Data and Safety Monitoring Board, Bristol-Myers Squibb. V. DeGruttola, member, Data and Safety Monitoring Board, Bristol-Myers Squibb study of entecavir; former consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb. J. Eron, consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; research grant from Merck.

Sources of support: The ACTG 368 clinical trial was conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (N01-AI-38858). Genotypic resistance testing was supported in part by NIH grants N01-AI-38858 (subcontract 203VC008), U01-AI-27658, RR-00044, and R01 AI-041387. Glaxo Smith Kline supplied abacavir; Merck & Co., Inc, supplied indinavir; and DuPont Merck provided efavirenz (now produced by Bristol-Myers Squibb). VircoLabs provided phenotypic resistance testing, and ABI provided sequencing kit reagents.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 11th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, San Francisco, CA, February 8-11, 2004

References

- 1.Staszewski S, Morales-Ramirez J, Tashima KT, et al. Efavirenz plus zidovudine and lamivudine, efavirenz plus indinavir, and indinavir plus zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. Study 006 Team. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(25):1865–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischl MA, Ribaudo HJ, Collier AC, et al. A Randomized Trial of 2 Different 4-Drug Antiretroviral Regimens versus a 3-Drug Regimen, in Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease (author list incorrect in original publication) J Infect Dis. 2003 Sep 1;188(5):625–634. doi: 10.1086/377311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulick RM, Ribaudo HJ, Shikuma CM, et al. Triple-nucleoside regimens versus efavirenz-containing regimens for the initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 29;350(18):1850–1861. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins GK, De Gruttola V, Shafer RW, et al. Comparison of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2003 Dec 11;349(24):2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walmsley S, Bernstein B, King M, et al. Lopinavir-ritonavir versus nelfinavir for the initial treatment of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 27;346(26):2039–2046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer SM, Bassett R, Squires KE, et al. A randomized trial of nelfinavir and abacavir in combination with efavirenz and adefovir dipivoxil in HIV-1-infected persons with virological failure receiving indinavir. Antivir Ther. 2003 Dec;8(6):507–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer SM, Vaida F, Bennett KK, et al. Dual vs single protease inhibitor therapy following antiretroviral treatment failure: a randomized trial. Jama. 2002 Jul 10;288(2):169–180. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulick RM, Hu XJ, Fiscus SA, et al. Randomized study of saquinavir with ritonavir or nelfinavir together with delavirdine, adefovir, or both in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults with virologic failure on indinavir: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 359. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(5):1375–1384. doi: 10.1086/315867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Cooper D, et al. Efficacy of enfuvirtide in patients infected with drug-resistant HIV-1 in Europe and Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 29;348(22):2186–2195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalezari JP, Henry K, O'Hearn M, et al. Enfuvirtide, an HIV-1 fusion inhibitor, for drug-resistant HIV infection in North and South America. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 29;348(22):2175–2185. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGruttola V, Dix L, D'Aquila R, et al. The relation between baseline HIV drug resistance and response to antiretroviral therapy: re-analysis of retrospective and prospective studies using a standardized data analysis plan. Antivir Ther. 2000;5(1):41–48. doi: 10.1177/135965350000500112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter JD, Mayers DL, Wentworth DN, et al. A randomized study of antiretroviral management based on plasma genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing in patients failing therapy. CPCRA 046 Study Team for the Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Aids. 2000;14(9):F83–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durant J, Clevenbergh P, Halfon P, et al. Drug-resistance genotyping in HIV-1 therapy: the VIRADAPT randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9171):2195–2199. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)12291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch MS, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: 2003 recommendations of an International AIDS Society-USA Panel. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Jul 1;37(1):113–128. doi: 10.1086/375597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DHHS. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitcomb JM, Huang W, Limoli K, et al. Hypersusceptibility to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in HIV-1: clinical, phenotypic and genotypic correlates. Aids. 2002 Oct 18;16(15):F41–47. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resch W, Ziermann R, Parkin N, Gamarnik A, Swanstrom R. Nelfinavir-resistant, amprenavir-hypersusceptible strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 carrying an N88S mutation in protease have reduced infectivity, reduced replication capacity, and reduced fitness and process the Gag polyprotein precursor aberrantly. J Virol. 2002 Sep;76(17):8659–8666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8659-8666.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leigh Brown AJ, Frost SD, Good B, et al. Genetic basis of hypersusceptibility to protease inhibitors and low replicative capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains in primary infection. J Virol. 2004 Mar;78(5):2242–2246. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2242-2246.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haubrich RH, Jiang H, Swanstrom R, et al. Non-nucleoside phenotypic hypersusceptibility cut-point determination from ACTG 359. HIV Clin Trials. 2007 Mar-Apr;8(2):63–67. doi: 10.1310/hct0802-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haubrich RH, Kemper CA, Hellmann NS, et al. The clinical relevance of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor hypersusceptibility: a prospective cohort analysis. Aids. 2002 Oct 18;16(15):F33–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulman N, Zolopa AR, Passaro D, et al. Phenotypic hypersusceptibility to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-experienced HIV-infected patients: impact on virological response to efavirenz-based therapy. Aids. 2001 Jun 15;15(9):1125–1132. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzenstein DA, Bosch RJ, Hellmann N, Wang N, Bacheler L, Albrecht MA. Phenotypic susceptibility and virological outcome in nucleoside-experienced patients receiving three or four antiretroviral drugs. Aids. 2003 Apr 11;17(6):821–830. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shulman NS, Bosch RJ, Mellors JW, Albrecht MA, Katzenstein DA. Genetic correlates of phenotypic hypersusceptibility to efavirenz among 446 baseline isolates from five ACTG studies. Antiviral Therapy. 2003 Abstract 43. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman NS, Bosch RJ, Mellors JW, Albrecht MA, Katzenstein DA. Genetic correlates of efavirenz hypersusceptibility. Aids. 2004 Sep 3;18(13):1781–1785. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200409030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark SA, Shulman NS, Bosch RJ, Mellors JW. Reverse transcriptase mutations 118I, 208Y, and 215Y cause HIV-1 hypersusceptibility to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Aids. 2006 Apr 24;20(7):981–984. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222069.14878.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tozzi V, Zaccarelli M, Narciso P, et al. Mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase potentially associated with hypersusceptibility to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors: effect on response to efavirenz-based therapy in an urban observational cohort. J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1;189(9):1688–1695. doi: 10.1086/382960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hertogs K, de Bethune MP, Miller V, et al. A rapid method for simultaneous detection of phenotypic resistance to inhibitors of protease and reverse transcriptase in recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with antiretroviral drugs. Antimicrobial Agents & Chemotherapy. 1998;42(2):269–276. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham S, Ank B, Lewis D, et al. Performance of the Applied Biosystems Viroseq Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) genotyping system for sequence-based analysis of HIV-1 in pediatric plasma samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(4):1254–1257. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1254-1257.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mracna M, Becker-Pergola G, Dileanis J, et al. Performance of Applied Biosystems ViroSeq HIV-1 Genotyping System for Sequence-Based Analysis of Non-Subtype B Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 from Uganda. J Clin Microbiol. 2001 Dec;39(12):4323–4327. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4323-4327.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Aquila RT, Schapiro JM, Brun-Vezinet F, et al. Drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top HIV Med. 2003 May-Jun;11(3):92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bacheler LT, Anton ED, Kudish P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutations selected in patients failing efavirenz combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(9):2475–2484. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2475-2484.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacheler L, Jeffrey S, Hanna G, et al. Genotypic correlates of phenotypic resistance to efavirenz in virus isolates from patients failing nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. J Virol. 2001 Jun;75(11):4999–5008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4999-5008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleim JP, Rosner M, Winkler I, et al. Selective pressure of a quinoxaline nonnucleoside inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) on HIV-1 replication results in the emergence of nucleoside RT-inhibitor-specific (RT Leu-74-->Val or Ile and Val-75-->Leu or Ile) HIV-1 mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(1):34–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang W, Gamarnik A, Limoli K, Petropoulos CJ, Whitcomb JM. Amino acid substitutions at position 190 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase increase susceptibility to delavirdine and impair virus replication. J Virol. 2003 Jan;77(2):1512–1523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1512-1523.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koval CE, Dykes C, Wang J, Demeter LM. Relative replication fitness of efavirenz-resistant mutants of HIV-1: Correlation with frequency during therapy and evidence of compensation for the reduced fitness of K103N+L100I by the nucleoside resistance mutation L74V. Virology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.021. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]