Abstract

In photosynthetic bacteria, light-induced electron transfer takes place in a protein called the reaction center (RC) leading to the reduction of a bound ubiquinone molecule, QB, coupled with proton binding from solution. We used electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) to study the magnetic properties of the protonated semiquinone, an intermediate proposed to play a role in proton coupled electron transfer to QB. To stabilize the protonated semiquinone state, we used a ubiquinone derivative, rhodoquinone, which as a semiquinone is more easily protonated than ubisemiquinone. To reduce this low-potential quinone we used mutant RCs modified to directly reduce the quinone in the QB site via B-branch electron transfer (Paddock et al. in Biochemistry 44:6920–6928, 2005). EPR and ENDOR signals were observed upon illumination of mutant RCs in the presence of rhodoquinone. The EPR signals had g values characteristic of rhodosemiquinone (gx = 2.0057, gy = 2.0048, gz ∼ 2.0018) at pH 9.5 and were changed at pH 4.5. The ENDOR spectrum showed couplings due to solvent exchangeable protons typical of hydrogen bonds similar to, but different from, those found for ubisemiquinone. This approach should be useful in future magnetic resonance studies of the protonated semiquinone.

1 Introduction

Light-induced electron transfer is responsible for conversion of light energy into chemical energy in photosynthesis. In photosynthetic bacteria, the initial photochemistry takes place in a protein called the reaction center (RC) and involves electron transfer from the primary electron donor, a bacteriochlorophyll dimer through a series of bound cofactors [1–3]. The structure of the RC shows roughly twofold symmetry with two groups of cofactors forming parallel pathways across the protein; an active group called the A branch and an inactive group called the B branch. Electron transfer normally occurs along the A branch from the primary donor, a bacteriochlorophyll dimer through bacteriochlorophyll then bacteriopheophytin to a primary ubiquinone, QA. The reduced then transfers an electron to a symmetrically related but weakly bound ubiquinone molecule QB that is connected to QA through an His-Fe2+ complex. Although QA and QB are both ubiquinone molecules and are symmetrically related in the RC, the functions of the two quinones are quite different [4, 5]. QA is reduced by the primary electron transfer reaction in ∼ 10−10 s with a quantum yield close to unity and normally only accepts one electron. QB is not directly reduced in the primary photochemistry but is reduced by on a much slower time scale (10−3−10−4 s). The full reduction of QB occurs in two one-electron transfer steps coupled to proton transfer to yield the fully reduced hydroquinone (see Eq. 1).

| (1) |

The mechanism for this reaction has been proposed consisting of a sequence of electron and proton transfer steps which involves an intermediate protonated semiquinone (QBH•) [6].

| (2) |

The first step is electron transfer from forming the anionic semiquinone . The second step is a reversible, transient protonation of the anionic semiquinone to form a higher energy protonated semiquinone intermediate QBH• which is easily reduced to form the stable QBH− state. Finally, the second protonation event leads to the fully reduced state. The work presented here is designed to study the magnetic resonance properties of the protonated semiquinone in bacterial RCs.

In solution, the protonated semiquinone species is unstable with respect to disproportionation into hydroquinone and quinone [7]. Consequently, in chemical systems the protonated semiquinone has been studied in transient or steady state populations resulting from formation either under ultraviolet illumination [8–10] or pulse radiolysis [11]. In addition, the protonated semiquinone has been observed by trapping at cryogenic temperature using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy [12] or infrared spectroscopy [13]. In native RCs containing ubiquinone, the protonated ubisemiquinone has never been observed. This is believed to be due to the low pKa for the protonated ubisemiquinone state. However, the presence of the protonated semiquinone was required to explain both the pH dependence and the electron driving force dependence of the rate of proton coupled transfer of the second electron to QB leading to the proposed proton coupled electron transfer reaction.

In order to overcome the low steady state population of the protonated semiquinone, Graige et al. [14] used a low potential quinone, rhodoquinone, which is expected to have a higher pKa value, to replace ubiquinone in the QB site. Its reduction required the use of a modified low potential QA. In this system, a protonated semiquinone intermediate state was observed by transient optical spectroscopy with a pKa of 7.5. The observed rate of the second electron transfer to the rhodosemiquinone decreased nearly tenfold per pH unit at pH values above this pKa consistent with the mechanism of electron transfer to the protonated semiquinone.

In this work, we used a new procedure for reducing rhodoquinone in the QB site that should be useful for magnetic resonance studies. A difficulty in the original system used by Graige et al. [14] is due to the low potential of rhodoquinone requiring the use of low potential analogues of QA in order to obtain electron transfer to QB. Besides the difficulty in binding different quinones in the QA and QB sites, a second complication arises due to incomplete electron transfer from to QB which would lead to background signals due to the radical. This results in EPR and electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectra containing an admixture of and signals.

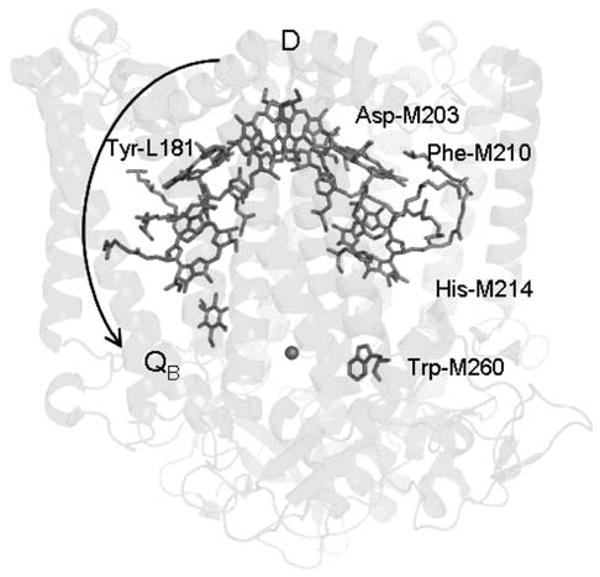

To avoid these difficulties, we developed a strategy to generate via direct electron transfer from bacteriopheophytin in the B branch using modified RCs in which the binding site of QA is eliminated and direct electron transfer to QB along the B branch is enhanced by suitable mutations [15]. The modified RC contains a total of five mutations and thus is called the quintuple mutant (see Fig. 1). Although the quintuple mutant RC has many modified residues, none of these changes is in the region around QB. Thus, we expect that the QB binding site in the mutant RCs to be similar to native. Support for the integrity of the QB environment comes from the crystal structure, the light-induced charge recombination rates, and the ENDOR spectrum of ubisemiquinone in the QB site, which are all similar for quintuple mutant and native RCs [15–17]. The resultant low quantum yield for reduction of QB (about 5%) could be overcome in these studies using continuous illumination in the presence of an electron donor resulting in nearly complete reduction of QB without an admixture of .

Fig. 1.

Structure of the quintuple RC. The cofactors and mutation sites are shown. The mutated residue Trp M260 is in the QA site and prevents QA binding. The other mutations enhance electron transfer directly to QB via the B-branch. Modified from Ref. [15] with permission. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society

In the experiments described in this work, rhodoquinone (RQ-3) was added to quintuple mutant RCs in which the Fe2+ was replaced with Zn2+ to eliminate broadening due to magnetic coupling. The RC was illuminated to generate the radical states and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The EPR and ENDOR spectra (80 K, Q-band) at neutral and high pH are characteristic of a semiquinone radical but differ in detail from those of the ubisemiquinone in the QB site. These signals are assigned to the anionic rhodosemiquinone. EPR spectra of the semiquinone showed changes at low pH (pH 4.5), which could be due to protonation of the rhodosemiquinone. The results show the potential for generating low potential radical species by reduction via the B-branch electron transfer.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Sample Preparation

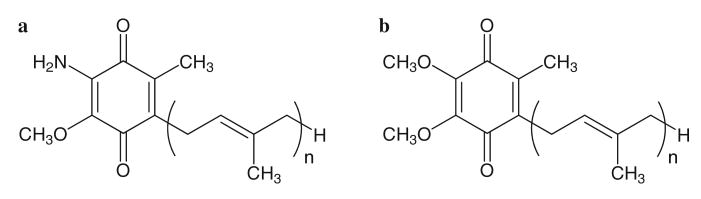

Rhodoquinone (RQ-3) was synthesized as described in Ref. [18]. It differs from ubiquinone in the substitution of an amino group for a methoxy group on the quinone ring (Fig. 2). The rhodoquinone radical anion in vitro (RQ•−, 1 mM) was generated electrochemically [19]. The coulometry of the quinone was performed using tetrabutylammonium fluoroborate (0.2 mol/l) as supporting electrolyte under high vacuum conditions in a home-built electrolysis cell. A mixture (1:1) of dimethoxyethane (DME, Fluka) and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF, Merck) was used as solvent. Both solvents were purified, distilled and dried over liquid Na/K alloy on high vacuum line. They were then distilled into the electrolysis cell from the high vacuum line. Electrochemical reduction was performed at room temperature under controlled potential using a platinum net and an uncoated silver wire as working and reference electrodes, respectively. A fraction of the obtained semiquinone anion radical solution was transferred to the Q-band EPR tube (outer diameter, 3 mm; inner diameter, 2 mm), which was finally plunged into liquid nitrogen and sealed under high vacuum conditions.

Fig. 2.

Structures of a rhodoquinone and b ubiquinone. In rhodoquinone, an amino group replaces a methoxy group on the ubiquinone ring. The rhodoquinone compound used in this study has n = 3

The RC protein was isolated from semi-aerobically grown cells of the quintuple B-branch mutant which includes the AWM260 mutation that excludes quinone from binding to the QA site. [15] The RCs were purified as described in Ref. [20] with an optical ratio OR = A280/A802 < 1.3. The isolated RCs were concentrated to A802 ∼ 200.

To perform EPR and ENDOR studies on , the high-spin Fe2+ was removed and replaced with diamagnetic Zn2+ as described by Debus et al. [21] and as modified by Utschig et al. [22]. Ubiquinone and ubisemiquinone were removed as described in Ref. [17]. The QB site was reconstituted with RQ-3 by adding a ∼ 10-fold excess. The concentrated stock was diluted 1:5 into 50 mM N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (CHES) buffer pH 9.5 for the high pH sample and 50 mM citrate pH 4.5 for the low pH sample, each containing 0.04% β-d-maltoside. The RC samples were illuminated in quartz EPR cells using a tungsten lamp (I ∼ 1 W/cm2) with a heat filter (1 in. water) for ∼ 5 s prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen. In these samples, residual metal and/or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) that remained from the metal replacement procedure acted as an external electron source that reduced D•+.

2.2 EPR and ENDOR Measurements

Continuous-wave (CW) EPR and ENDOR measurements at Q-band (35 GHz) and 80 K were performed in San Diego. The spectrometer is a home-built superheterodyne-type instrument with a Varian klystron, a cylindrical TE011 brass cavity, and an immersion Dewar system for temperature control. The cavity and coupler is similar to one described by Sienkiewicz et al. [23]. A Li:LiF sample was used as a primary g value standard (g = 2.00229) [24], and P-doped Si as a secondary standard (g = 1.99891 at 80 K) [25]. The P–Si marker was permanently attached to the bottom wall of the cavity. ENDOR experiments were performed with the EPR spectra 50% saturated. ENDOR spectra were recorded at the magnetic field position as indicated in the corresponding traces, using frequency modulation (FM) of ±140 kHz, at a FM rate as indicated in the figure caption. The output of the radio-frequency (RF) amplifier (ENI 3100L) feeding the ENDOR coils was 50 W.

EPR measurements of rhodosemiquinone (RQ•−) in vitro (T = 80 K) were performed in Mülheim using a pulsed Q-band (34 GHz) Bruker ELEXSYS E580 spectrometer with a Super Q-FT microwave bridge equipped with a homebuilt resonator similar to that used in the laboratory of San Diego. Field-swept free induction decay (FID)-detected EPR spectra were recorded using a hole-burning microwave (MW) pulse of 1,000 ns (π/2).

3 Results

3.1 EPR Spectra

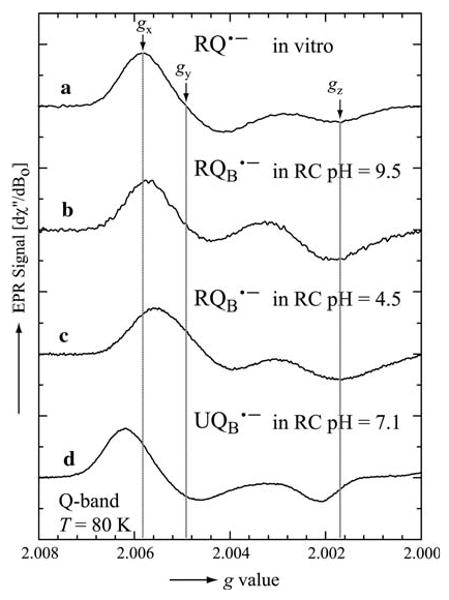

Figure 3a shows the EPR spectrum of the rhodosemiquinone anion radical (RQ•−) in nonprotic solvents (DME/MTHF). At Q-band, the rhodosemiquinone EPR signal displays a characteristic g anisotropy with principal g values of 2.0058 (gx), 2.0049 (gy) and 2.0017 (gz). These values are different to those corresponding to the ubisemiquinone anion radical (UQ•−) in nonprotic solvents (see Table 1) [19]. The difference in g values of RQ•− and UQ•− shows that the spin density distribution in the rhodosemiquinone is different than that in the ubisemiquinone. This is probably due to the difference between the electronic properties of amine group in RQ and methoxy group in UQ (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

EPR powder spectra of rhodosemiquinone and ubisemiquinone at 80 K. a RQ•− in nonprotic organic solvents, b in quintuple mutant RCs at pH 9.5, c (or RQBH•) in quintuple mutant RCs at pH 4.5 and d in quintuple mutant RCs at pH 7.1. Both gx and gy differ between the and samples and show slight shifts between pH 9.5 and 4.5. Experimental conditions: a MW frequency = 33.87 GHz, MW power = 3.2 × 10−4 W, spectrum obtained by pseudo-modulating the field-swept FID-detected EPR spectrum with 0.15 mT (see Sect. 2.2), average of 2 scans, 40 s per scan. The others: MW frequency = 35.03 GHz, MW power = 1 × 10−7 W, field modulation = 0.15 mT peak-to-peak at 270 Hz. Number of scans: b 7, c 29 and d 100. Scan time: 20 s

Table 1.

g-Tensor principal values of quinone related radicals in RCs of Rb. sphaeroides and of model systems in nonprotic organic solvent

| g value (±0.0001) | Rb. sphaeroidesa | Model systems | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (pH 7.0) | (pH 9.5) | (pH 4.5) | UQ•−b | RQ•−c | |

| gx | 2.0062 | 2.0057 | 2.0055 | 2.0070 | 2.0058 |

| gy | 2.0053 | 2.0048 | 2.0045 | 2.0054 | 2.0049 |

| gz | 2.0021 | – | – | 2.0020 | 2.0017 |

Values could not be measured accurately due to the overlapping with a small fraction of D•+ (see Fig. 3b, c)

Values obtained in this work using quintuple mutant RCs, in which the high-spin Fe2+ was replaced by diamagnetic Zn2+

Values corresponding to ubiquinone-3 (UQ-3) as taken from Ref. [19]

Values obtained in this work using rhodoquinone-3 (RQ-3)

The RC samples containing RQB had the high-spin Fe2+ replaced by Zn2+. The semiquinone state was generated by illumination and then the samples were quickly frozen. Figure 3b shows the Q-band EPR spectrum of the RC sample prepared at pH 9.5. At this frequency, the low-field (gx and gy) region of the spectrum is due to the semiquinone radical, whereas the region near gz can contain contributions of the donor radical D•+ [17]. The amount of D•+ was variable. Thus, we focus on the regions near gx and gy which are reflective of the semiquinone states. The EPR signal obtained at pH 9.5 is attributed to that of due to the absence of a signal in parallel samples made without the addition of RQ and the similarity to that of RQ•− in vitro (see Fig. 3a, b). The measured g values are 2.0057 (gx) and 2.0048 (gy). The spectra from samples made at pH 8.0, 7.5 and 6.0 all resembled that from the sample at pH 9.5 (not shown). However, the g values of (gx and gy) differ significantly from those of (Fig. 3d). This is in line with the observations in model systems (see Table 1). Thus, the structural difference between the quinones is also responsible for the difference in g values of and .

To search for conditions under which the rhodosemiquinone is protonated, quintuple mutant RCs containing RQ were illuminated at lower pH values. No changes in the EPR spectra measured at 80 K were observed at pH 6 (data not shown) where rhodosemiquinone has been reported to be protonated in room temperature experiments. However, a small shift in values of gx from 2.0057 to 2.0055 and gy from 2.0048 to 2.0045 were measured in the lower pH 4.5 sample (see Fig. 3b, c; Table 1). These changes may be due to protonation of the rhodosemiquinone.

3.2 ENDOR Spectra

In addition, we used ENDOR spectroscopy to measure the magnetic interaction of the semiquinone with the protein surrounding (e.g., with hydrogen bonded protons). This technique has recently been used to characterize in detail the hydrogen bonding situation of [26]. Furthermore, it was used to monitor local conformational changes associated with the electron-transfer reaction involving one of the hydrogen bonds to [17].

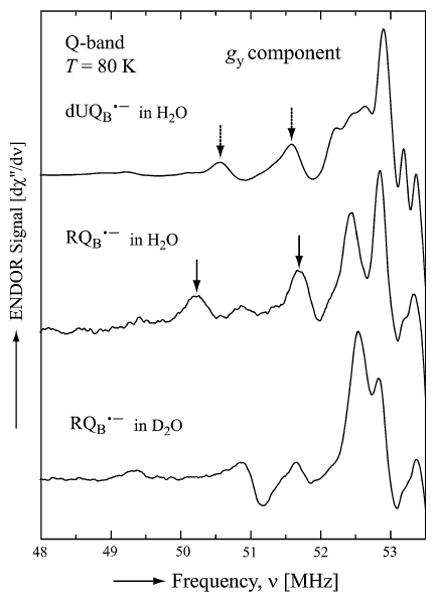

Figure 4 shows the Q-band 1H ENDOR spectra of illuminated quintuple mutant RCs containing UQ or RQ. These spectra were measured by monitoring the EPR spectrum at the magnetic field position corresponding to gy (see Fig. 3a) where the largest semiquinone ENDOR signals are obtained and contributions from donor radical signals are negligible. Since deuterated ubiquinone-10 was used, only exchangeable protons and protons of the protein matrix contribute to the 1H ENDOR spectrum of (see Fig. 4, top trace). The lines outside the matrix region (i.e., between 48.5 and 52 MHz) were previously assigned to protons in hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl oxygens of the semiquinone (for details see Paddock et al. [17]). The peaks at 50.6 and 51.6 MHz (indicated by arrows) were attributed to the perpendicular components of the hyperfine coupling tensors associated with the H-bonded protons. The shifts of these peaks from the proton Larmor frequency (∼ 53.2 MHz) represent a direct measure of the couplings between the electron in and the hydrogen bonded protons.

Fig. 4.

ENDOR powder spectra of and in quintuple mutant RCs. Arrows indicate the couplings between exchangeable protein protons that form H-bonds with (upper trace) and proposed to form H-bonds with (middle trace). Assignment of these latter peaks to H-bonds is supported by their absence upon exchange into D2O (lower trace). Spectra recorded at the magnetic field position corresponding to gy (see Fig. 3). Experimental conditions: T = 80 K, MW frequency = 35.03 GHz, MW power = 3 × 10−6 W, frequency modulation (FM) = ±140 kHz at a rate of 947 Hz. Number of scans: 18,000 (top), 500 (middle) and 2,600 (bottom). Scan time: 4 s

Figure 4, middle trace shows the 1H ENDOR spectrum of (i.e., the RC sample prepared at pH 9.5). Similar spectra were obtained from the RC samples prepared at pH 8.0, 7.5 and 6.0 (not shown). Since protonated rhodoquinone was used, the ENDOR spectrum has contributions from all protons, i.e., exchangeable protons, protons of the protein matrix and nonexchangeable protons on the quinone. The peaks at 50.2 and 51.7 MHz (indicated by arrows) seem to belong to hydrogen-bonded protons due to their line shape and position, i.e., they seem to be related to the perpendicular components of the H-bond tensors. The assignment of these peaks to hydrogen bonding protons is supported by their absence in the 1H ENDOR spectrum of the RC sample prepared in D2O, i.e., the protons were exchanged by deuterons (see Fig. 4, bottom trace). The couplings measured for are different than those measured for . This is probably due to the difference in spin density at the hydrogen-bonded oxygen atoms between and . The difference in spin density was also manifested in the EPR spectra of and . However, a change due to differences in the H-bond distances or orientations cannot be ruled out.

4 Discussion

In this work, we utilized modified RCs to reduce the low potential quinone, rhodoquinone in the QB site to facilitate studies of the protonated semiquinone state which is important for understanding the mechanism of proton coupled electron transfer (Eq. 2). Quintuple mutant RCs were used in this study which have mutations that block the binding of QA and enhance electron transfer to QB directly from the B-branch bacteriopheophyin. RCs reconstituted with RQ-3 and illuminated while freezing to cryogenic temperatures displayed an EPR signal with g values characteristic of in vitro rhodosemiquinone. The ENDOR spectrum of shows a pattern of couplings due to hydrogen bonding protons that are similar to those observed for suggesting that the hydrogen bonding to the anionic rhodosemiquinone is similar to that for ubisemiquinone. These results show the potential of this system to reduce low potential quinones in the QB site that are not readily reduced in the native RC.

Initial attempts were made to look for the effects of protonation by performing the reaction at variable pH. Although the rhodosemiquinone was reported to be protonated at pH 7.5 based on transient optical measurements at room temperature, no changes in low-temperature EPR or ENDOR spectra were observed until the pH was much lower (pH 4.5). The difficulty in forming the protonated semiquinone at cryogenic temperature may be due to the temperature dependence of the protonation reaction. This result is consistent with the suggestion that the protonation step is energetically unfavorable (higher enthalpy) and that the QB site stabilizes the negatively charged anionic semiquinone state [27].

We have done preliminary ENDOR measurements on the rhodosemiquinone in the RC at lower pH values. Changes in the spectrum have been observed at pH 4.5 which need to be understood by studying model compounds. To do this, we have initiated a study together with Wolfgang Lubitz, of the EPR and ENDOR spectra of the rhodosemiquinone in organic solutions in order to assign the ENDOR lines in the RC and are also investigating the EPR and ENDOR spectra of protonated semiquinones in the solid state to elucidate the interactions of this species with its surroundings. The results should provide further insights into the proton and electron transfer reactions in bacterial photosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wolfgang Lubitz (Max Planck Institute for Bioinorganic Chemistry, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany) for continuing collaboration on magnetic resonance studies of quinones in RCs and dedicate this paper to him on the occasion of his 60th birthday. We also thank Jens Niklas and Christoph Laurich (Max Planck Institute for Bioinorganic Chemistry, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany) for measurements of the in vitro rhodosemiquinone. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM 41637).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

M. L. Paddock, Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

M. Flores, Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA, Max-Planck Institute for Bioinorganic Chemistry, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

R. Isaacson, Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

J. N. Shepherd, Department of Chemistry, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA 99258, USA

M. Y. Okamura, Email: mokamura@ucsd.edu, Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA.

References

- 1.Blankenship RE. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis. Blackwell; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feher G, Allen JP, Okamura MY, Rees DC. Nature (London) 1989;339:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunner M. Curr Top Bioenerg. 1991;16:319–367. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamura MY, Feher G. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:861–896. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.004241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wraight C, Gunner M. In: Advances in Photosynthesis and Photorespiration. Hunter CN, Daldal F, Thurnauer MC, Beatty JT, editors. Vol. 28. Springer; Dordrecht: 2009. pp. 379–405. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graige M, Paddock M, Bruce J, Feher G, Okamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9005–9016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers JQ. In: The Chemistry of Quinoid Compounds. Patai S, Rappoport Z, editors. Wiley; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridge NK, Porter G. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A. 1958;244:276–288. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SK, Sytnyk W, Wan JKS. Can J Chem. 1972;50:3052–3057. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gough TE. Trans Faraday Soc. 1965;62:2321–2326. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Land EJ, Swallow AJ. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:1890–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hales BJ, Case EE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;637:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burie J, Boussac A, Boullais C, Berger G, Mattioli T, Mioskowski C, Nabedryk E, Breton J. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:4059–4070. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graige MS, Paddock ML, Feher G, Okamura MY. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11465–11473. doi: 10.1021/bi990708u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paddock ML, Chang C, Xu Q, Abresch E, Axelrod H, Feher G, Okamura M. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6920–6928. doi: 10.1021/bi047559m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paddock ML, Flores M, Isaacson R, Chang C, Abresch EC, Selvaduray P, Okamura MY. Biochemistry. 2006;47:14032–14042. doi: 10.1021/bi060854h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paddock ML, Flores M, Isaacson R, Chang C, Abresch EC, Axelrod HL, Okamura MY. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8234–8243. doi: 10.1021/bi7005256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cape JP, Strahan JR, Lenaeus MJ, Yuknis BA, Le TT, Shepherd JN, Bowman MK, Kramer DK. Biochemistry. 2005;45:34654–34660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimz O, Lendzian F, Boullais C, Lubitz W. Appl Magn Reson. 1998;14:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paddock ML, McPherson PH, Feher G, Okamura MY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6803–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Debus RJ, Feher G, Okamura MY. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2276–2287. doi: 10.1021/bi00356a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Utschig L, Greenfield S, Tang J, Laible P, Thurnauer M. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8548–8558. doi: 10.1021/bi9630319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sienkiewicz A, Smith BG, Veselov A, Scholes CP. Rev Sci Instrum. 1996;67:2134–2138. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stesmans A, Van Gorp G. Rev Sci Instrum. 1989;60:2949–2952. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feher G, Gere EA. Phys Rev. 1959;114:1245–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores M, Isaacson R, Abresch E, Calvo R, Lubitz W, Feher G. Biophys J. 2007;92:671–682. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu Z, Gunner M. Biochemistry. 2005;44:82–96. doi: 10.1021/bi048348k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]