Summary

It is well known that head trauma may cause hearing loss, which can be either conductive or sensorineural. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and olfactory dysfunction due to head trauma are also well known. The association between sensorineural hearing loss and anosmia, following head trauma, is extremely rare. Two rare cases of post-traumatic occurrence of hearing loss, olfactory dysfunction and benign positional vertigo are reported and the pathophysiology of the association between sensorineural hearing loss, anosmia and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, after head injury, are briefly discussed. ENT specialists should, in the Authors’ opinion, be aware of the possible association between anosmia, sensorineural hearing loss and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after head injury, even in the absence of skull fracture.

Keywords: Anosmia, Sensorineural hearing loss, Vertigo, Head trauma

Riassunto

I traumi cranici possono associarsi ad ipoacusia che può essere sia neurosensoriale che trasmissiva. È noto che sia la vertigine parossistica posizionale benigna che l’alterazione della capacità olfattiva possono essere conseguenza di un trauma cranico. L’associazione tra ipoacusia neurosensoriale ed anosmia dopo trauma cranico è molto rara. Descriviamo 2 casi in cui dopo trauma cranico entrambi i pazienti hanno presentato ipoacusia neurosensoriale, alterazione olfattiva e vertigine posizionale benigna e discutiamo brevemente i meccanismi fisiopatologici di tale associazione. Pensiamo sia giusto sottolineare la possibilità che anosmia, ipoacusia neurosensoriale e vertigine parossistica posizionale benigna possano presentarsi in associazione dopo trauma cranico anche senza frattura ossea.

Introduction

Post-traumatic hearing loss is a well known occurrence 1. All head injuries, with or without skull base fracture, may cause hearing loss which, in both instances, can be conductive as well as sensorineural 2. The site of the hearing impairment can be peripheral or central and the patho-physiology of hearing loss, after skull trauma, may be multiple. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo due to head trauma is a well-known occurrence. Head injury is also a common cause of olfactory dysfunction.

The present report focuses on two cases of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and anosmia following traumatic head injury.

Case reports

Case 1

In September 2005, a 40-year-old male was referred to our Department complaining of hearing loss and anosmia following head trauma which had occurred nine days previously on account of a pedestrian casualty. The patient reported smelling loss, left ear tinnitus, vertigo after head movements to the right, without hearing loss or earache. Otoscopy revealed the external left auditory canal partially covered by dry blood and mild hyperaemia of the left tympanic membrane; the rest of the ear, nose and throat (ENT) and neurovestibular examination was normal. The neurological examination was also normal, apart from the indicated alterations of the first and eighth cranial nerves. Pure tone audiometry showed a severe left SNHL and a moderate right SNHL (Fig. 1); pure tone average (PTA), calculated for 0.5, 1, 2, 3 KHz, was 71.25 dB on the left ear and 58.75 dB on the right ear. A previous pure tone audiometry performed at the age of 25 years (routine screening) was, bilaterally, within the normal range (right and left PTAs: 20 dB). Middle ear impedance, measured by tympanometry, showed Jerger type-A curves in both ears. Controlateral stapedius reflexes were bilaterally absent. Neither spontaneous nor positional nystagmus were detected. The patient had undergone temporal bone computerized tomography (CT) which did not show temporal bone fractures and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, brainstem, cerebellum-pontine angles, internal auditory canals and olfactory area that ruled out abnormalities. Oral steroid treatment was prescribed but was refused by the patient who was then treated with oral A, C, E vitamins, ginkgo biloba and phospholipids twice a day (Otobrain® Farmila-Thea Farmaceutici, Settimo Milanese, Italy) for 3 months without any improvement.

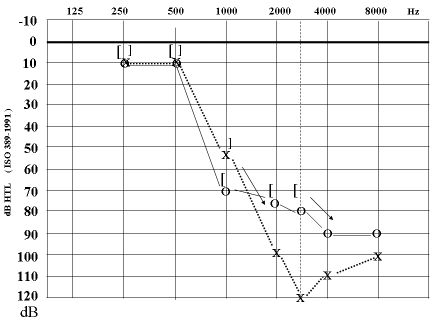

Fig. 1.

Case 1. Pure tone audiometry (left PTA 71.25 dB, right PTA 58.75 dB).

In February 2006, as the patient continued to complain of loss of smell, rhinological evaluation was performed. Direct nasal endoscopy did not show any anatomical alteration which could explain anosmia. Peak nasal inspiratory flow showed flows of 170 l/min which were normal for the patient’s age, height and sex, according to Ottaviano et al. 3. A basal anterior active rhinomanometry showed no abnormal nasal resistences. Le Nez du Vin was then performed according to McMahon and Scadding 4, which we normally use as a quick test of olfaction. As the patient gave more than one wrong answer, the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test was performed. Since the patient gave only 9 correct answers, we concluded that the patient was affected by anosmia according to Doty et al. 5.

Eighteen months after the occurrence of the head trauma, the patient, who still complained of a clear-cut loss of smell, with hearing loss, was re-evaluated: the otological and neurological examinations did not show any clinical modifications, pure tone audiometry was unchanged, the auditory brainstem response test (ABR) (120 dB nHL bilateral click stimulation) showed a wave-form consistent with cochlear hearing loss. Speech audiometry (speech material: two-syllabic words) was performed. The left and right speech-reception threshold (SRT) were 40 dB and 30 dB, respectively. The video-nystagmographic gaze test did not show spontaneous nystagmus. Apogeotropic positional nystagmus was detected at the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre on the right side, compatible with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPV) of the right posterior semicircular canal. Saccades were normal. Tracking test was normal. A caloric test, performed by irrigating each auditory external canal with cool (+30°C) and warm (+44°C) water, showed a normal response.

Case 2

In March 2007, a 57-year-old female was referred to our Department complaining of bilateral hearing loss, anosmia, hypogeusia and vertigo following head trauma occurred 7 months before due to a pedestrian casualty. Otoscopy was normal. Nasal endoscopy showed a slight deformity of the septum and large inferior turbinates without abnormalities in the olfactory area. Peak nasal inspiratory flow showed flows of 120 l/min which were below normal values for patient’s age, height and sex3. The patient gave 3 wrong answers to Le Nez du Vin test. At the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, the patient gave only 10 correct answers and we concluded that the patient was affected by anosmia. Neurological examination was normal, apart from the indicated alterations of the first and eighth cranial nerves. A post-traumatic CT brain scan showed a bilateral contusion of the frontal cerebral region (Fig. 2) and fracture of the occipital squama. Pure tone audiometry, performed 1 month earlier, in another Institution showed a moderate bilateral SNHL [PTA was 45 dB bilaterally].

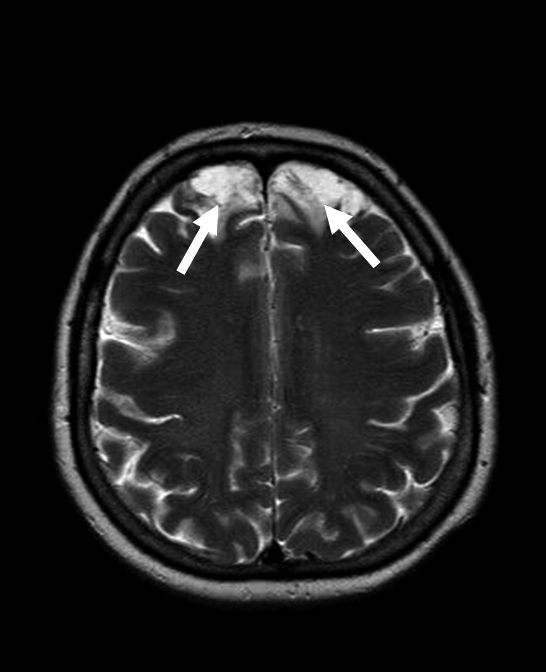

Fig. 2.

Post-traumatic CT scan of brain showing bilateral contusion of frontal cerebral region.

As trauma had occurred 7 months earlier, no therapy was suggested to the patient. The patient was submitted to further pure tone audiometry, speech audiometry, ABR, videonystagmography, temporal bone CT scan and gadolinium-enhanced MRI of brain, brainstem, cerebellum-pontine angles, internal auditory canals and olfactory area. The pure tone audiometry showed a bilateral SNHL. The right ear PTA was 40 dB, the left ear 43.75 dB (Fig. 3). Left and right ear SRT were 20 dB. ABR confirmed the cochlear origin of bilateral hearing loss. Videonystagmography showed a left post-traumatic BPV. Temporal bone CT scan disclosed a right petrous apex fracture with involvement of the otic capsule (Fig. 4). Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the central nervous system confirmed the bilateral contusion of the frontal lobes without other abnormalities (Fig. 5).

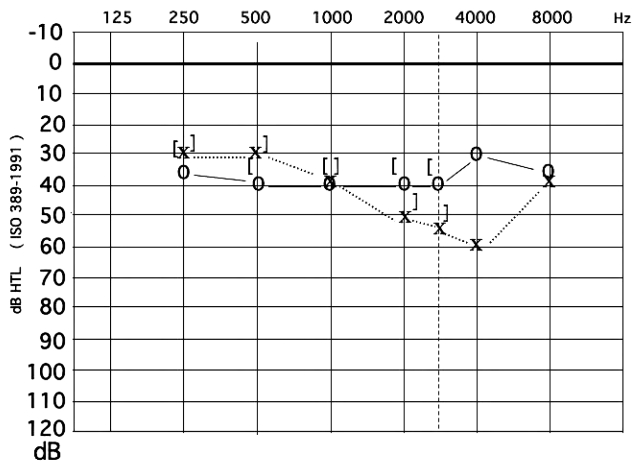

Fig. 3.

Case 2. Pure tone audiometry (left PTA 43.75 dB, right PTA 40 dB).

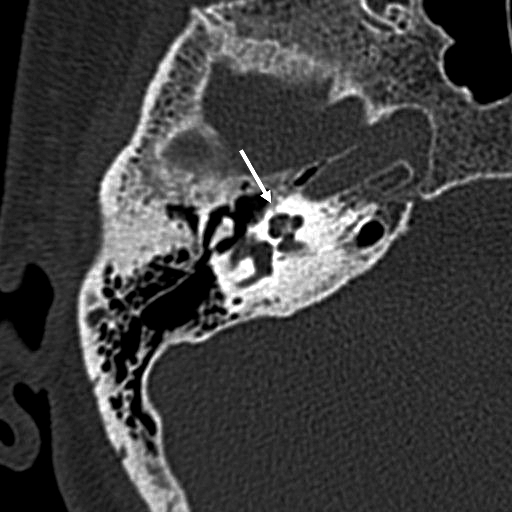

Fig. 4.

CT scan of temporal bone showing right petrous apex fracture with involvement of otic capsule.

Fig. 5.

T2-weighted MRI of central nervous system showing bilateral contusion of frontal lobes.

Head injuries may cause hearing loss which can be either conductive or sensorineural.

After these kinds of traumas, the middle ear or cochlea appear to be the most frequently involved areas. In these cases, the hearing loss is most commonly due to a temporal bone fracture with involvement of the otic capsule or with disruption of the ossicular chain. Nevertheless, the forces created by the trauma may also force the stapedial foot inwards through the oval window 6 and, in some cases, may cause rupture of the round or oval window membranes leading to perilymphatic fistula. It is also well known that an increase in cerebrospinal fluid pressure may be transmitted to the inner ear via the cochlear aqueduct or through the internal auditory canal 7 or by way of the endolymphatic sac 6 leading to damage in the organ of Corti. Elevated intra-cranial pressures together with direct injuries to blood vessels and thrombosis may also reduce the blood supply to the inner ear 8 9. The eighth cranial nerve may also be damaged contributing to hearing impairment 10.

Post-mortem histopathological studies in patients who have suffered head injury have shown abnormalities of the internal auditory canal, inner ear tissues, eighth nerve and brainstem. Considering a limited series of 8 autopsy cases, Makishima and Snow, in 1976, described, in 3 cases, the presence of blood in the scala tympani and, in 1 case of nubeculae, in scala vestibuli. They also found haemorrhage (6 cases), laceration (5 cases) and oedema (1 case) of the eighth nerve. Herniation (2 cases), haemorrhage (4 cases), softening (5 cases) and oedema (1 case) of the brain stem have also been described 11.

Reviewing the clinical features of 240 cases of BPV, in 1987, Baloh et al. 12 found that the first diagnostic category was post-traumatic: these patients presented the onset of BPV within 3 days of well-documented head trauma. From a physiopathological viewpoint, it is easy to conceive that head trauma could throw otoconial debris into different canals and be frequently responsible for BPV of the posterior semicircular canal.

Head injury is also a common cause of olfactory dysfunction. In 1997, Doty et al., following revision of 268 patients who had suffered head trauma, reported that anosmia occurred in about 66.8% of the cases and that rarely olfactory function became normal again 5. During the trauma, either shearing of olfactory filaments (as they pass through the cribiform plate) or contusion to the olfactory bulb may occur. Moreover, contusion or a shearing injury to the cerebral cortex (frontal and temporal lobes) may occur 5 13 14. According to Zusho 13, 55.2% of post-traumatic anosmia are not associated with facial or skull fractures.

The association between SNHL and anosmia, following head trauma is extremely rare. Kittel, in 1961, and Khul and Krauss, in 1969, reported, separately, two cases of bilateral SNHL, anosmia and vertigo due to a bilateral vestibular areflexia after head injury 15 16. From the ENT examination and the clinical and radiological examinations, it seems that, in our first case, the bilateral SNHL may most probably be explained by bilateral cochlear damage, as well as the left SNHL, in the second case. In the second patient, the right SNHL may be due to the temporal bone fracture with the involvement of the otic capsule. In the first case, anosmia seems to be most probable consequence of olfactory filament shearing while, in the second one, it could be explained by the contusion of the olfactory bulb as well as of the frontal lobes, revealed by imaging. In both cases, clinical and videonystagmographic evidence of post-traumatic BPV was found.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald DC. Head trauma: hearing loss and dizziness. J Trauma 1996;40:488-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergemalm P-O, Borg E. Long-term objective and subjective audiologic consequences of closed head injury. Acta Otolaryngol 2001;121:724-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottaviano G, Scadding GK, Coles S, Lund VJ. Peak nasal inspiratory flow. Normal range in adult population. Rhinology 2006;44:32-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon C, Scadding GK. Le Nez du Vin – a quick test of olfaction. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1996;21:278-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doty RL, Yousem DM, Pham LT, Kreshak AA, Geckle R, Lee WW. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with head trauma. Arch Neurol 1997;54:1131-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergemalm PO. Progressive hearing loss after closed head injury: a predictable outcome? Otolaryngol 2003;123:836-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchese-Ragona R, Marioni G, Ottaviano G, Gaio E, Staffieri C, de Filippis C. Pediatric sudden sensorineural hearing loss after diving. Auris Nasus Larynx 2007;34:361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilberg CV. Inner ear hearing loss following blunt head injury. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg) 1977;56:323-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownson RJ, Zollinger WK, Madeira T, Fell D. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss following manipulation of the cervical spine. Laryngoscope 1986;96:166-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith MV. The incidence of auditory and vestibular concussion following minor head injury. J Laryngol Otol 1979;93:252-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makishima K, Snow JB. Histopathologic correlates of otoneurologic manifestations following head trauma. Laryngoscope 1976;86:1303-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baloh RW, Honrubia V, Jacobson K. Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology 1987;37:371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zusho H. Posttraumatic Anosmia. Arch Otolaryngol 1982,108:90-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costanzo RM, Becker DP. Smell and taste disorders in head injury and neurosurgery patients. In: Meiselman HL, Rivlin RS, editors. Clinical Measurements of Taste and Smell. New York: Macmillan; 1986. p. 565-78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kittel G. Bilateral deafness with vestibular disorders and anosmia after blunt skull trauma. Z Laryngol Rhinol Otol 1961;40:515-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhl KD, Krauss J. Loss of hearing, vestibular functional loss and anosmia following blunt cranial trauma. Zentralbl Chir 1969;22:1610-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]