Abstract

Pharmacotherapy is a critical adjunct to smoking cessation therapy. Little is known about relative preferences for these agents among smokers in primary care settings.

In the context of a population-based clinical trial, we identified 750 smokers in primary care practices and independent of their stage of change offered them a free treatment course of either bupropion or transdermal nicotine replacement (TNR). Smokers opting for pharmacotherapy completed standardized contraindication screens that were reviewed by the patient's primary care physician.

Most participants (67%) requested pharmacotherapy. Use of pharmacotherapy was positively associated with higher nicotine dependence and readiness to quit. Of the smokers requesting pharmacotherapy, 51% requested bupropion and 49% requested TNR. Choice of bupropion was related to no history of heart disease and no previous use of bupropion. Although potential contraindications to treatments were identified for 21.7% of bupropion and 6.6% or TNR recipients, physicians rarely felt that these potential contraindications precluded the use of these agents.

When cost is removed as a barrier, a large proportion of rural smokers are eager to use smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, especially agents that they have not tried before. Although some comorbid conditions and concurrent drug therapies were considered contraindications, particularly to bupropion, physicians rarely considered these clinically significant risks enough to deny pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking cessation, pharmacotherapy preference, nicotine replacement, bupropion

Current treatment guidelines recommend that pharmacotherapy should be offered to all smokers interested in quitting unless contraindicated (Henningfield & McLellan, 2005; George & O'Malley, 2004). Until recently, bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) were the only FDA approved pharmacological therapies for smoking cessation (Ahluwalia, Harris, Catley, Okuyemi, & Mayo, 2002; Fiore et al., 2004). Use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation has increased in the past decade, nonetheless, smoking cessation pharmacotherapy remains underutilized with less than one out of five smokers using drug therapy when making a quit attempt (Zhu, Melcer, Sun, Rosbrook, & Pierce, 2000; Cummings & Hyland, 2005).

Nationally, nicotine patches account for 49% of pharmacologically assisted quit attempts, followed by the nicotine gum (28%) and bupropion (21%) (Cummings & Hyland, 2005). These findings are based on surveys of past quit attempts (Hyland et al., 2004), may be influenced by cost and availability, and may not reflect personal preferences. Additional studies of patients in rural primary care settings reflect national data in that patients were much more likely to report experience with use of NRT than bupropion (Ellerbeck et al., 2003), but physicians were much more likely to discuss bupropion than NRT as a treatment option (Ellerbeck, Ahluwalia, Jolicoeur, Gladden, & Mosier, 2001). Of the few reports to date on individuals' preferences for smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, the majority focus on preferences for varying forms of nicotine replacement (West et al., 2001; Fagerstrom, Tejding, Westin, & Lunell, 1997). No study has prospectively assessed relative preferences for bupropion versus NRT when access and cost have been removed as potential confounding variables.

Potential contraindications to drug treatment could also influence observed utilization of drugs. In clinical trials testing the efficacy of NRT or bupropion many patients have been excluded due to potential contraindications or cautions to smoking cessation pharmacotherapy (Ahluwalia, Harris, Catley, Okuyemi, & Mayo, 2002; Hurt et al., 1997; Tonnesen et al., 2003). Little is known about the prevalence of these potential contraindications in primary care settings or how these might influence access to effective pharmacotherapy.

Although nearly 25% of the U.S. population lives in rural communities (Sarvela, Cronk, & Isberner, 1997), and the prevalence of cigarette smoking in rural areas is higher than in suburban or urban communities (Eberhardt et al., 2001) few initiatives have focused on helping rural smokers quit. Rural communities have not seen the same decrease in smoking prevalence that has been experienced in urban communities (Doescher, Jackson, Jerant, & Gary Hart, 2006). Rural smokers are at a greater risk for tobacco-related morbidity and mortality than smokers in urban areas, in part because they lack access to medical services (KHDE, 2004) and support for smoking cessation.

The purpose of the present study is to examine factors associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapy utilization and preferences when offered at no cost to patients seen in rural primary care practices. Among smokers who requested pharmacotherapy, we examine relative preference for bupropion versus nicotine replacement and explore factors correlated with these preferences. Finally, we examine the frequency of potential contraindications to bupropion and nicotine patch and how the presence of these potential contraindications influenced physician's decisions to recommend treatment.

Methods

Design

The current study was completed as part of KanQuit, a population-based clinical trial of a disease-management program for smoking cessation among rural smokers. This three-arm, randomized clinical trial evaluated the effect on smoking cessation of: (a) usual care, (b) limited counseling plus feedback to physicians, and (c) intensive counseling plus feedback to physicians. All study participants were offered free pharmacotherapy. Hence, utilization data are drawn from participants in all study arms.

Participants

Trained medical students on rural preceptorships recruited smokers from 50 rural primary care clinics throughout the state of Kansas within the Rural Primary Care Practice and Research Program. The preceptorships are part of this program, founded in 1992 to offer research and educational opportunities to medical students. Nearly all (97/105) Kansas counties are rural and the 50 rural primary care practices for this study were selected from this network to test a new intervention. Most (78%) of the practices were located in counties designated as frontier, rural or densely settled rural according to the 5-strata Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) population density categories (frontier, rural, densely settled rural, suburban, and urban) (KHDE, 2004) The remaining practices were located in remote parts of counties designated as urban or semi-urban. Of these, 7 were in remote geographic regions within those counties and 4 were in larger towns (population 15,000-50,000) geographically separated from the five metropolitan municipalities within the state.

Medical students were posted at clinics for 6-8 weeks in order to shadow physicians in rural practice. Recruitment began in the Summer of 2004 and ended in the Fall of 2005. Students do not see every patient, but they attempt to see most because the purpose of the preceptorship is to see as broad an array of patients and complaints as possible. Students were directed to assess smoking status, and screen for eligibility, with every patient they saw independent of the patients' interest in stopping smoking.

Study eligibility requirements were kept to a minimum in order to include the broadest possible range of rural smokers. Students screened patients for smoking status, determined eligibility, and obtained informed consent from eligible smokers. To be eligible for KanQuit, participants had to: (1) have been smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day; (2) have smoked at least 25 of the last 30 days; (3) be at least 18 years of age; (4) not be pregnant or planning to become pregnant in the next two years; (5) not be planning on moving in the next two years; (6) have a home telephone or a cellular telephone; (7) consider one of our participating physicians to be their regular doctor; and (8) not be residing in the same household as another participant.

The participant information was forwarded to the KanQuit research staff. The staff contacted the participants via telephone, verified eligibility, and conducted a baseline survey. Out of 1826 smokers identified by medical students in the primary care clinics 41% were identified as eligible and were invited to participate and 17% refused to participate. The most frequent reasons for ineligibility include smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day (43.2%), primary care physician was not participating in the study (23.3%), smoking 25 out of the past 30 days (14.0%), and planning to move (13.4%).

Pharmacotherapy

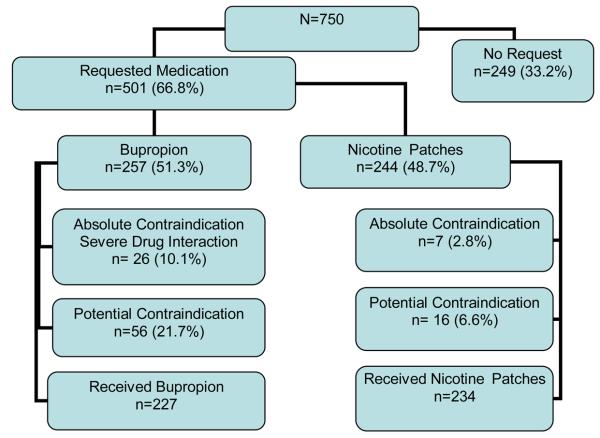

All participants were offered a choice between nicotine patch and bupropion at baseline (see Figure 1). All participants received information on the availability, directions for use, and risks and benefits of the two medications at the beginning of the study as part of the informed consent procedures. In addition, they received information about both types of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy via mailed education materials sent at baseline.

Figure1.

Flow-chart of participants throughout the process of requesting medication.

Treatment consisted of a 6-week course of the nicotine patch at a 21mg/24 hour dose or a 7-week course regimen of bupropion at 300mg/day. Participants could indicate their intention to use pharmacotherapy by either returning a stamped postcard included with study educational materials or calling research staff at a toll-free number.

If a participant requested the nicotine patch, research staff screened for absolute or potential contraindications via the telephone. Absolute contraindications included: severe eczema or serious skin conditions, allergy to nicotine patch, pregnancy, breastfeeding, heart attack in the past 2 months, ongoing angina, peptic ulcer disease, arrhythmia, or uncontrolled blood pressure. Potential contraindications included stroke in the past 6 months, insulin therapy, and a current diagnosis of liver, kidney or heart disease. Participants reporting an absolute contraindication were ineligible for the drug and were offered the option of bupropion. Research staff faxed a list of any potential contraindications to the primary care physician who either approved or disapproved the drug for the participant.

If a participant requested bupropion, research staff screened for absolute and potential contraindications via the telephone. Absolute contraindications included current use of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor or a history of seizures, allergy to bupropion, eating disorder, severe head trauma, central nervous system tumor, or binge drinking. Potential contraindications included: the use of benzodiazepines in the past 2 weeks, heart attack in the past 2 months, angina, irregular hear beat, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, drug dependency, physician diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder and potential drug-drug interactions. To identify potential drug interactions with bupropion, participants' current medications were reviewed by a registered pharmacist utilizing the Micromedex database. Participants with absolute contraindications for bupropion were denied bupropion and offered the option of the nicotine patch. For participants with potential contraindications, research staff faxed a list of potential contraindications and drug interactions along with a prescription request form to the participants' primary care physician. Physicians made the final determination for or against bupropion and, if approved, faxed back the signed prescription.

Subjects were advised to report any adverse events to a toll-free number. Adverse events were also assessed on follow-up calls six months after entry into the study. Follow-up calls were completed on 89.5% of participants.

Measures

The data for this study were derived from an in-depth baseline survey that was administered over the telephone by trained research staff who were not the participants' counselors.

Outcome Measures

The outcome measure for our first analysis was whether participants requested pharmacotherapy. We compared two groups of participants: those participants who requested pharmacotherapy by either returning a stamped postcard or calling research staff at a toll-free number and those who did not request pharmacotherapy. The second outcome measure of the study was pharmacotherapy preference. Among participants requesting pharmacotherapy we identified those who requested bupropion versus nicotine patches.

Independent Variables

We assessed demographic characteristics including age, gender, education level, and employment status. Smoking history was assessed by number of cigarettes smoked per day and previous use of nicotine replacement and bupropion. Nicotine dependence was assessed using the 6-item Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991). The FTND is a brief and reliable measure of degree or severity of nicotine dependence.

Importance of and confidence in quitting smoking was assessed using a 10-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating greater importance or confidence (Rollnick, Butler, & Stott, 1997). Furthermore, evaluation of stage of readiness to stop smoking (Prochaska et al., 1994) was based on a 5-item assessment, in which the individual was classified according to one of the Transtheoretical Model stages of change (DiClemente et al., 1991): precontemplation (not currently thinking of stopping smoking), contemplation (considering stopping in the next 6 months), preparation (planning to stop within the next month), action (stopped smoking within the past 6 months), maintenance (abstinent from smoking for more than 6 months). The presence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, stroke, chronic lung disease, heart disease, cancer, or depression was determined by participant self-report.

Data Analyses

Baseline data were analyzed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We conducted frequency counts to describe the prevalence of request for pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy preferences. Frequency counts were also used to describe potential contraindications to bupropion and nicotine patches. Bivariate analyses were conducted separately for the two primary outcomes: smoking cessation pharmacotherapy use and pharmacotherapy preference. We used logistic regression to estimate the relationship between psychosocial factors, smoking behaviors and previous pharmacotherapy use with both outcome variables.

Results

The majority of the study participants were white (89.4%), under 50 years of age, female, and employed (Table 1). Almost half of the sample had some education beyond high school. The majority of our sample smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day, was contemplating quitting, and was highly motivated (M=8.64; SD=2.05) and somewhat confident (M=6.10, SD=2.70) about quitting. Most participants had previously used either NRT or bupropion to stop smoking. Approximately one third of the participants had self-reported depression, high cholesterol, hypertension, or chronic lung disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population and factors associated with medication request among rural smokers. N (%)

| Total Sample N=750 N (%) |

No Medication Requested n=249 (33.2) |

Medication Requested n=501 (66.8) |

OR(95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 50 years old | 310 (41.3) | 111 (44.5) | 199 (39.7) | 0.82(0.60 – 1.11) | |

| Male | 311 (41.5) | 99 (39.7) | 212 (42.3) | 1.15(0.81-1.51) | |

| Employed | 503 (67.1) | 165 (66.3) | 338 (67.5) | 1.056(0.76-1.46) | |

| > high School | 365 (48.6) | 117 (46.9) | 248 (49.5) | 1.10(0.81-1.49) | |

| ≥ 20 Cigarette per day | 576 (76.8) | 183 (73.5) | 393 (78.4) | 1.31(0.92-1.87) | |

| FTND** | ≥6 | 343 (45.7) | 100 (40.1) | 243 (48.5) | 1.40(1.03-1.91) |

| Motivation**** | ≥ 5 | 719 (95.8) | 223 (89.6) | 496 (99.0) | 11.56(4.32-30.51) |

| Confidence** | ≥ 5 | 579 (77.2) | 182 (73.0) | 397 (79.2) | 1.40(0.98-2.00) |

| Stage Change**** | |||||

| Pre-contemplation | 65 (8.7) | 46(18.5) | 19(3.79) | 0.18(0.10-0.32) | |

| Contemplation* | 457 (60.9) | 139 (55.8) | 318 (63.5) | ||

| Preparation | 228 (30.4) | 64 (25.7) | 164 (32.7) | 1.12(0.78-1.52) | |

| Previous use Bup** | 245 (32.6) | 68 (27.3) | 177 (35.3) | 1.45(1.04-2.03) | |

| Previous NRT use*** | 397 (52.9) | 113 (45.4) | 284 (56.7) | 1.57(1.16-2.14) | |

reference group;

p≤.05;

p≤.01;

p≤.001

FTND – Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, Bup – bupropion, NRT – nicotine replacement therapy

Of the 750 participants, 501 (66.8%) requested smoking cessation pharmacotherapy (Figure 1). Participants requesting medication were more highly nicotine dependent, motivated, confident and in a more advanced stage of change than persons who did not request pharmacotherapy (Table 1). Participants who had previously used either bupropion or NRT were also more likely to request medication.

Among the 501 participants who requested smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, there was similar preference for the nicotine patch (n=244, 48.7%) and bupropion (n=257, 51.3%) (see Figure 1). Sociodemographic factors had little influence on the smoker's preference for the nicotine patch versus bupropion (Table 2). Compared to those who requested the nicotine patch, participants that requested bupropion were less likely to have a history of heart disease or a prior history of bupropion use.

Table 2.

Relationship between patient's characteristics and odds of requesting nicotine patch (n=244, 48.7%) and Bupropion* (n=257, 51.3%) (*ref group)

| Total N N (%) |

NRT n=244(48.7) |

Bupropion N=257(51.3) |

OR(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥50 years old | 199 (39.7) | 104 (42.6) | 95 (36.9) | 0.79(0.55 – 1.13) |

| Male | 212 (42.3) | 105 (43.0) | 107 (41.6) | 0.94(0.66 – 1.34) |

| Employed | 338 (67.9) | 156 (64.2) | 182 (71.4) | 1.39(0.95 – 2.00) |

| ≥ High School | 248 (49.5) | 116 (47.5) | 132 (51.4) | 1.16(0.82 – 1.65) |

| Diabetes | 69 (13.8) | 37 (15.2) | 32 (12.5) | 0.79(0.47 – 1.32) |

| Heart Disease* | 48 (9.6) | 30 (12.3) | 18 (7.0) | 0.54(0.29 – 0.99) |

| Hypertension | 158 (31.5) | 80 (32.8) | 78 (30.4) | 0.89(0.61 – 1.30) |

| High Cholesterol | 182 (36.3) | 93 (38.1) | 89 (34.6) | 0.86(0.60 – 1.24) |

| Stroke | 19 (3.8) | 12 (4.9) | 7 (2.7) | 0.54(0.21 – 1.40) |

| Cancer | 19 (3.8) | 11 (4.5) | 8 (3.1) | 0.67(0.27 – 1.75) |

| Depression | 200 (39.9) | 101 (41.4) | 99 (38.5) | 0.88(0.62 – 1.27) |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 140 (27.9) | 72 (29.5) | 68 (26.5) | 0.86(0.58 – 1.27) |

| ≥20 Cigarettes per day | 393 (78.4) | 200 (81.9) | 193 (75.1) | 0.66(0.43 – 1.02) |

| Previous use Bup**** | 177 (35.3) | 100 (40.9) | 77 (29.9) | 0.62(0.43 – 0.89) |

| Previous NRT use | 284 (56.7) | 143 (58.6) | 141 (54.9) | 0.86(0.60 – 1.22) |

p≤.05;

p≤.01;

p≤.001

Bup – bupropion, NRT – nicotine replacement therapy

Of the 244 participants requesting the nicotine patch, 7 (2.9%) were found to have an absolute contraindication. Potential contraindications were more common with a total of 20 (8.1%) reporting one or more of the following: stroke in the past six months (n=2, 0.8%), taking insulin (n=8, 3.1%), liver disease (n=2, 0.8%) or a diagnosis of heart disease (n=8, 3.1%). After physicians reviewed faxed information on potential contraindications, only 2 participants were not approved to receive the nicotine patch. In total, 9 (3.9%) of the 244 smokers were denied the nicotine patch on the basis of absolute or potential contraindications.

Of 257 participants requesting bupropion, 10.1% (N=24) had an absolute contraindication. Absolute contraindications included: history of seizures (n=11, 4.4%), severe head trauma (n=1, .4%) and binge drinking (n=12, 4.9%). Another 21.7% of participants requesting bupropion had potential contraindications to bupropion, including use of benzodiazepines in the past two weeks (n=19, 7.8%), diabetes, (n=21, 8.6%), rapid or irregular heart beat (n=7, 2.3%), stroke (n=5, 2.0%), bipolar mood disorder diagnosed by physician (n=8, 3.3%), cancer (n=4, 1.6%), and drug dependency (n=3, 1.2%). Less than 1% reported high blood pressure, liver disease, kidney disease, or significant weight loss associated with depression. We identified potential drug interactions with bupropion (n=37, 14.3%): the most common were use of antidepressants (6.3%) and inhaled steroids (4.3%). After reviewing information on potential contraindications, including potential drug interactions, physicians authorized bupropion for all but 10 of these participants. In total, 10 (3.9%) of 257 smokers requesting bupropion were denied this treatment based on the presence of absolute or potential contraindications. After six months of follow-up, no serious drug-related adverse events were reported.

Discussion

When cost is removed as a barrier, a large proportion of rural smokers are eager to use smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, especially agents that they have not tried before. Although some comorbid conditions and concurrent drug therapies were considered potential contraindications, particularly to bupropion, physicians rarely considered these clinically significant to deny pharmacotherapy. This study represents one of the first to examine uptake of pharmacotherapy among smokers seen in primary care when barriers to pharmacotherapy access have been minimized. Nationwide, approximately 38% smokers from urban areas report trying pharmacotherapy in their lifetime (Zhu, Melcer, Sun, Rosbrook, & Pierce, 2000; Cummings & Hyland, 2005; Bansal, Cummings, Hyland, & Giovino, 2004), however, requests for pharmacotherapy in our study were much higher. Our findings are consistent with others in suggesting that improvements in access, such as offering free drug treatment, can enhance utilization of effective smoking cessation therapies.(Mcfee et al., 2006; Deprey et al., 2006) Because most (70%) of smokers see a physician in any given year, this affords a unique opportunity to discuss pharmacotherapy options.

The use of pharmacotherapy in this study was also enhanced by the implementation of a unique pharmacotherapy screening process. We used standardized screening tools that discriminated between absolute and potential contraindications. By identifying participants subjects with ‘absolute contraindications’ to a given drug, these screeners ensured a level of safety that might not be present in a typical primary care setting (e.g. identifying all patients with a history of seizure disorders and making sure they don't receive bupropion). This systematic screening revealed that many participants had potential contraindications or cautions to the use of bupropion and nicotine replacement pharmacotherapy (e.g., a history of heart disease, stroke or potential drug interactions). Many of these individuals would have been excluded from other smoking cessation studies (Hurt et al., 1997; Tonnesen et al., 2003). In our study, however, when participants were identified as having one of these contraindications, we communicated directly with the primary care physician, described the potential concern, and used the physician's knowledge of the patient's medical condition to determine the appropriateness of the pharmacotherapy. Based on this communication, the number of participants who were not provided with pharmacotherapy was much lower than in previous studies. No serious adverse events related to pharmacotherapy use were reported during this study. Hence this process appears to enhance access to pharmacotherapy without compromising safety.

We identified a number of patient-specific factors related to smoking cessation pharmacotherapy utilization. Participants who were more nicotine dependent, motivated, and confident and those who had previously used smoking cessation pharmacotherapy were more likely to request pharmacotherapy. Future studies should examine whether enhancing motivation or confidence can produce higher rates of medication utilization over time – an important predictor of cessation success.

We are unaware of any prior studies that have examined the choice of NRT versus bupropion when both agents were readily accessible and offered free of charge. Although population surveys suggest that most smokers utilize NRT for quit attempts, this may be highly influenced by the more ready access to over-the-counter NRT products. In contrast, studies derived from pharmacotherapy prescription databases may underestimate NRT received without prescription (Holtrop, Wadland, Vansen, Weismantel, & Fadel, 2005). In our study approximately equal numbers of smokers requested bupropion and NRT. Although we found few variables that predicted use of a given medication, one factor that did appear to be associated with choice was prior experience with a given drug. In this study, smokers appeared to be more interested in trying a treatment that they had not used before.

This study has several limitations. First, participants were offered only one type of NRT. Although the transdermal nicotine patch is the most popular form of nicotine replacement (Bansal, Cummings, Hyland, & Giovino, 2004), if we had offered more types of NRT, we might have seen a greater interest in nicotine replacement compared to bupropion, Second, this study was conducted prior to the approval of varenicline as smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and we cannot be sure how the availability of this new drug would have affected overall uptake or choice of pharmacotherapy. Third, two-thirds of the participants in this study did receive some type of telephone counseling. This counseling could have influenced pharmacotherapy uptake. Fourth, even though all the patients requesting a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy received it by mail, we do not have data on whether it was used, or how much was used. Finally, we were not able to determine rural versus urban differences in utilization because we only had a rural sample. This would be a good focus for future studies.

Offering free medications and including the smoker's primary care physician in the process of evaluating potential contraindications, facilitated high utilization of effective pharmacotherapy without compromising safety. Should this approach be used more widely in research and clinical practice, it may be possible to increase use of effective pharmacotherapy and consequently achieve higher quit rates among all smokers in primary care. Screening procedures used in this study enhanced smoking cessation pharmacotherapy use without compromising safety and should be incorporated in other studies as well as in clinical practice. Partnering with patients' physicians to implement similar procedures might also be a useful mechanism for tobacco quitlines in order to optimize pharmacotherapy use and smoking cessation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grant 5 R01 CA101963-04 and was presented in part at the February 2006, Society Research on Nicotine and Tobacco in Orlando, Florida. Partial support for the pharmacotherapy utilized in this study was provided by GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal MA, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Giovino GA. Stop-smoking medications: who uses them, who misuses them, and who is misinformed about them? Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S303–310. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KM, Hyland A. Impact of nicotine replacement therapy on smoking behavior. Annuals Review Public Health. 2005;26:583–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprey TM, Bush T, Grossman H, Mahoney L, McAfee T, Zbikowski SM, Cushing C. Who calls when free NRT is offered: The Oregon Patch initiative; Paper presented at the 12nd Conference of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Orlando, Florida, USA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, Gary Hart L. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. Journal of Rural Health. 2006;22(2):112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt ID, Makuc DM, et al. Urban and Rural Health Chartbook: Health United States. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2001. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbeck EF, Ahluwalia JS, Jolicoeur DG, Gladden J, Mosier MC. Direct observation of smoking cessation activities in primary care practice. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50(8):688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbeck EF, Choi WS, McCarter K, Jolicoeur DG, Greiner A, Ahluwalia JS. Impact of patient characteristics on physician's smoking cessation strategies. Preventive Medicine. 2003;36(4):464–470. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KDHE . Primary care: Health professional underserved areas report. In: Health OoLaR, editor. Office of Local and Rural Health. Kansas Department Health and Environment; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Tejding R, Westin A, Lunell E. Aiding reduction of smoking with nicotine replacement medications: hope for the recalcitrant smoker? Tobacco Control. 1997;6(4):311–316. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.4.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, Jackson TC, Zehner ME, Jorenby DE, Mielke M, et al. Integrating smoking cessation treatment into primary care: an effectiveness study. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(4):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TP, O'Malley SS. Current pharmacological treatments for nicotine dependence. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2004;25(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield JE, McLellan AT. Medications work for severely addicted smokers: implications for addiction therapists and primary care physicians. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtrop JS, Wadland WC, Vansen S, Weismantel D, Fadel H. Recruiting health plan members receiving pharmacotherapy into smoking cessation counseling. American Journal Managed Care. 2005;11(8):501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, et al. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(17):1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Li Q, Bauer JE, Giovino GA, Steger C, Cummings KM. Predictors of cessation in a cohort of current and former smokers followed over 13 years. Nicotine Tobacco and Research. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S363–369. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcfee T, B. T, Bush T, Deprey M, Grossman H, Zbikowski S, McClure J, Cushing C. Quitlines and NRT; Paper presented at the 12nd Conference of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Orlando, Florida, USA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Butler CC, Stott N. Helping smokers make decisions: the enhancement of brief intervention for general medical practice. Patient Education and Counseling. 1997;31:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)01004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvela PD, Cronk CE, Isberner FR. A secondary analysis of smoking among rural and urban youth using the MTF data set. Journal of School Health. 1997;67(9):372–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb07178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Tonstad S, Hjalmarson A, Lebargy F, Van Spiegel PI, Hider A, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year study of bupropion SR for smoking cessation. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2003;254(2):184–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hajek P, Nilsson F, Foulds J, May S, Meadows A. Individual differences in preferences for and responses to four nicotine replacement products. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;153(2):225–230. doi: 10.1007/s002130000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Melcer T, Sun J, Rosbrook B, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation with and without assistance: a population-based analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]